“Creating in my head”: How Lillian Schwartz turned Life’s Obstacles into Opportunities

Lillian Schwartz working at her home computer circa 2010. / THF706855

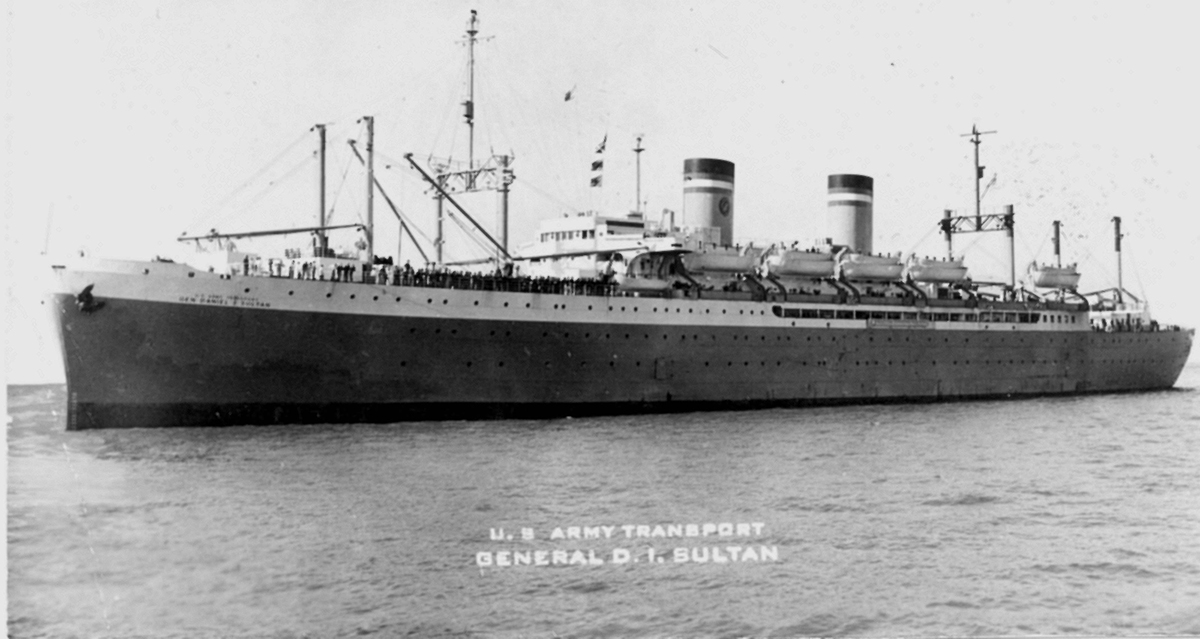

In 1949, Lillian Schwartz — an artist who became well known for her experimental spirit — packed her bags and boarded the U.S. Army transport ship General Daniel I. Sultan. Lillian's husband, Jack Schwartz, was a doctor and military service member. Several months earlier, he took up a new station in a pediatric hospital far from his home in New Jersey — in Fukuoka, Japan. Lillian and her young son now made the lengthy trek to join him there. Ten days of worry about seasickness, dysentery and their safety aboard a military vessel passed as they crossed the Pacific Ocean.

U.S. Army transport ship General Daniel I. Sultan. Lillian sailed on this ship to join her husband, Jack, in Japan in 1949. / THF611239

Soon after arriving, Lillian displayed troubling medical symptoms. A pounding headache and fever grew more severe, and her family rushed her to the hospital. Doctors placed Lillian under quarantine and diagnosed her with poliomyelitis, or polio. After such an arduous journey to reunite with her family, she was in pain and alone. Her body was partially paralyzed.

The hospital in Fukuoka, Japan, where Lillian recovered from polio. This view is from 2008. / THF705899

It took Lillian several long months to recover. Between physical therapy and extended bed rest, she often received a visitor. His name was Tshiro, a Zen practitioner and calligrapher. Tshiro taught Lillian how to meditate and convinced her she could practice calligraphy, too. But how could she paint without moving her hands? She would have to start with the mind.

“On the Yangtze” by Lillian Schwartz, circa 1949. Lillian practiced some of her calligraphy on old paper. / THF628853

Tshiro taught Lillian to visualize the calligraphy brush, imagining the contact between brush and paper. Mentally, she mastered the art long before she picked up the pen. Slowly, Lillian regained her mobility. Soon after, she painted this haunting canvas, "After Polio." The skeletal faces of polio patients emerge from a hazy background, working to recover their mobility with the help of nursing staff. It wouldn't be long before Lillian embarked on a successful artistic career, mastering traditional and experimental mediums alike and creating innovative works of computer art.

“After Polio” by Lillian Schwartz, circa 1950. / THF193129

By early spring 1950, Lillian could finally move again, and in March she and her family returned to the United States. Still, she continued to experience health issues. She developed post-polio syndrome, a condition that causes fatigue and muscle weakness. Doctors also discovered an adenoma — a type of noncancerous tumor — on Lillian's thyroid gland. By 1955, abstract shapes had begun to disrupt Lillian's vision, reminding her of Pablo Picasso's paintings. The culprit was chorioretinitis, a type of inflammation in the eye's retina that leaves scar tissue behind.

Doctors in the United States suspected Lillian's health conditions were the result of radiation exposure from her time in Japan. The town of Fukuoka, where Lillian had lived, is located between Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Atomic bombs destroyed both cities during the Second World War. Survivors who remained near their homes and people visiting the area experienced the negative effects of lingering radiation, which was poorly understood.

X-ray images of Lillian Schwartz’s hands, November 1974. / THF706035

Post-polio syndrome and chorioretinitis reshaped Lillian's world, but Lillian refused to let them defeat her. Instead, she learned to work with her disabilities, incorporating them into her artistic practice.

Lillian applied her calligraphy skills directly to her later work. In 1972, she accepted a commission to create a five-story kinetic sculpture for Bell Laboratories commemorating physicists Clinton Joseph Davisson and Lester H. Germer. The original design for the commission, called "Wave Motion," began with an ink sketch. The fluid curves and elegant form borrow directly from Lillian’s calligraphy practice.

“Wave Motion” ink sketch by Lillian Schwartz. / Photograph courtesy of the author.

The principles required to create calligraphy — precision and, above all, patience — were skills Lillian applied to her computer art and films, but meticulous attention to detail wasn't the only element that defined Lillian’s artistic practice.

Chorioretinitis affected her vision in such a way that her depth perception made it difficult to distinguish between two and three dimensions. Disrupted vision heightened her awareness of these elements in her films "UFOs" and "Enigma." In these works, strobing, saturated colors almost overwhelm the eye, creating flashy after-images. In her video "Beyond Picasso," she even unpacked Picasso's painterly techniques, which were so like the visuals from the scar tissue in her eyes. Lillian shared her unique way of seeing the world, blazing a groundbreaking trail for computer artists.

“UFOs” by Lillian Schwartz, 1971. / THF500602

“Enigma” by Lillian Schwartz, 1972. / THF500610

Lillian's interests evolved over time, and she never stopped making art — even when her mobility began to decline with age. Instead, she found support among her family and formed a network of collaborators who learned from and assisted Lillian with new work. In her 80s, Lillian directly addressed some of her concerns about aging by creating born-digital art. In July 2023, Lillian turned 96 years old. She still enjoys doodling as a creative outlet. Lillian never lets anything — including age or disability — stand in the way of her artistic spirit.

“Deaf and Old” by Lillian Schwartz. / THF611241

Further Reading

The Computer History Museum. Oral History Project: Interview with Lillian Schwartz (2013).

Schwartz, Lillian. The Computer Artist's Handbook (New York: W.W. Norton & Company). 1992.

CJ Martonchik created this content during their 2023 Simmons Graduate Internship at the Henry Ford.