Demystifying Washington: An Ordinary Man in Extraordinary Times

On April 30, 1789, 235 years ago, in the nation’s first capital of New York, George Washington was sworn in as the first president of the newly formed United States of America. From that moment on, many aspects of Washington’s legacy would be built on myth, leaving out important parts of history that would help us understand the man and tell a fuller story. This isn’t to say that Washington didn’t do extraordinary things in his lifetime. Still, when we peel away the layers, we find that he was an ordinary man who lived in exceptional times and wasn’t as perfect as he is often portrayed.

Washington was born on February 22, 1732, on Popes Creek Plantation, (also known as Wakefield) in Westmoreland County, Virginia. In 1734, the Washington family moved to another property they owned, Little Hunting Creek Plantation, which was later renamed Mount Vernon. While Washington never received a formal education, he did have access to books and a private tutor. At the same time, he studied geometry and trigonometry on his own, for his first job as a surveyor.

At age 11, he inherited 10 enslaved people from his father. They were considered property, not people. Washington practiced chattel slavery throughout his life, buying, selling, renting and hunting enslaved people, including Ona Judge. Slavery in the United States would not be outlawed until the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865, and even then, it was still used as a punishment.

Washington rose to military fame during the French and Indian War — the American theater of the Seven Years' War between England and France. In 1752, with no previous military experience, Washington was made commander of the Virginia Militia. During the French and Indian War, he was in charge of all of Virginia’s military forces. In 1759, he married Martha Dandridge Custis, a young, wealthy widow who also brought many enslaved people with her into the marriage. When the Revolutionary War began, Martha began to supervise domestic operations at Mount Vernon.

In 1775, with the American Revolution in full force, the Continental Congress called on Washington to command the Continental Army. Martha would often join him at various military camps to entertain guests and build the soldiers' morale. He and his men famously crossed the Delaware in the dead of winter and, with the help of the Oneida Nation — who traveled hundreds of miles to bring them food — survived the harsh winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge. Finally, after eight long years, the British surrendered in 1781, resulting in victory for the newly formed United States and thrusting Washington into the national spotlight as an American hero. In 1783, after the Treaty of Paris was signed, sealing independence, Washington resigned from his post.

George Washington’s camp bed (1775-1780) was used during the American Revolution. / THF13451

In 1789, Washington was called upon to serve as the new nation's first president. He served two terms, setting a precedent that was followed until the historic third term election of President Franklin Roosevelt (after which the 22nd Amendment was passed limiting the president to two terms). During his presidency, Washington nominated John Jay as the first chief justice of the Supreme Court, established the first national bank and created the first presidential cabinet. Under his leadership, the Bill of Rights was ratified, the Jay Treaty was negotiated and five states were added to the Union. While Washington was creating and setting the stage for future presidencies, partisanship between Federalists and Anti-Federalists was growing. He believed in respectful discourse and discussion within the government, but the growing divide between political parties concerned him. In his farewell address, he noted this issue:

“However [political parties] may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.” — September 17, 1796

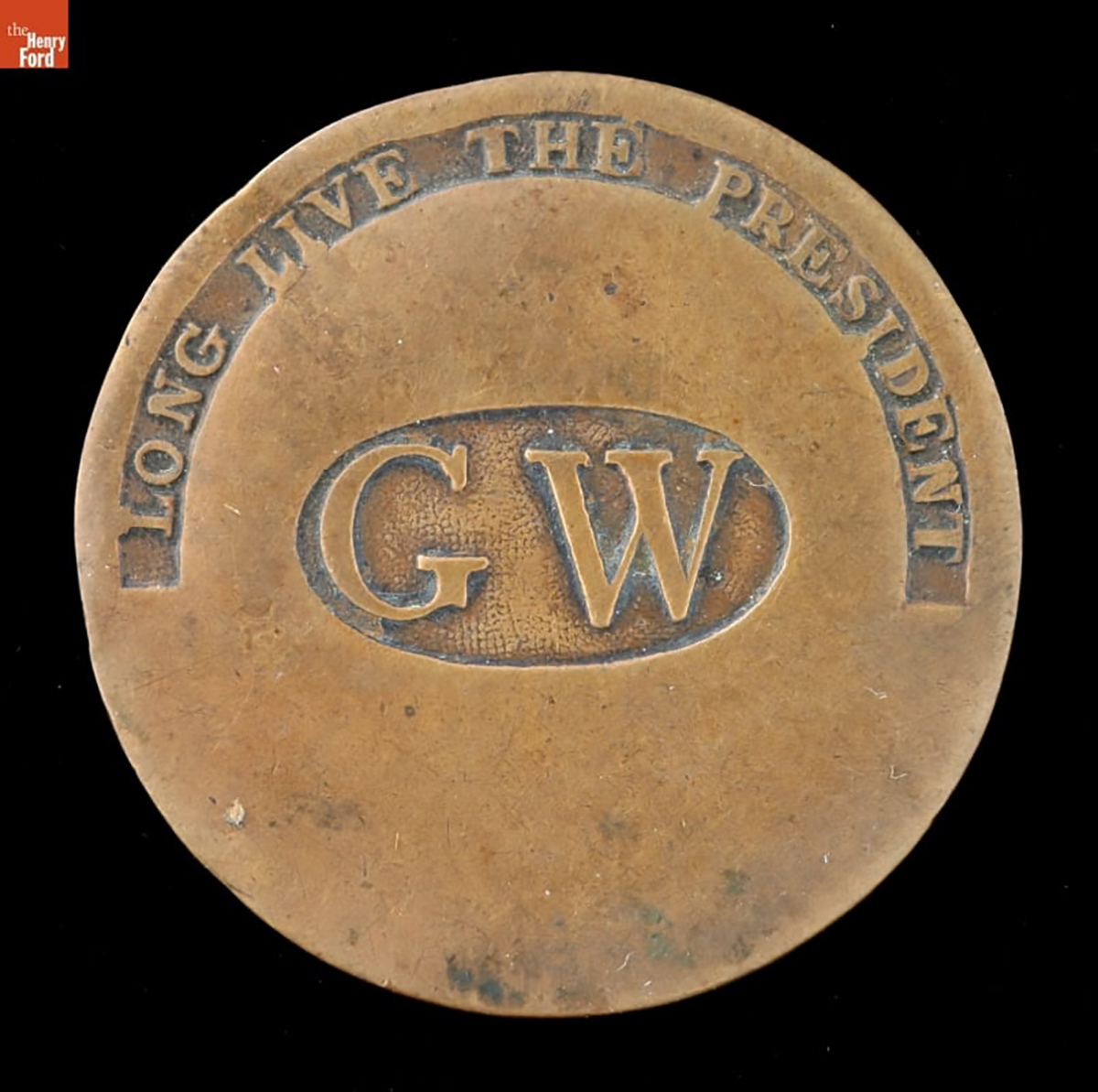

George Washington presidential inauguration button (1789-1793). / THF6975

During his presidency, Washington received Indigenous diplomatic delegations at his home in Philadelphia. These delegations shared their concerns that settlers were not respecting boundaries outlined in treaties. Washington shrugged these issues off, commenting that only a line of military troops would keep settlers out. Believing that Indigenous people were “savages” that should assimilate and become "civilized" or be removed, Washington was forceful about what he wanted from the nations — and that was land. After Mohawk Chief Joseph Bryant visited, he warned other native nations to be cautious: “General Washington is very cunning; he will try to fool us if he can. He speaks very smooth, will tell you fair stories, and at the same time want to ruin us.” The Seneca referred to him as "Conotocarious," meaning “Town Destroyer,” a name also given to his great-grandfather. Washington was instrumental in significant land losses and participated in questionable land deals, particularly in Lenapehoking — the place that we now call New York.

Washington’s legacy is complex. As the first president of the United States, he set many precedents and helped to create the stage that all future presidents would abide by. But he was also a plantation owner who enslaved people, and he was instrumental in Indian removal. He was a man who lived during extraordinary times and someone from whom we can learn cautionary lessons. Please visit George Washington's Mount Vernon to learn more.

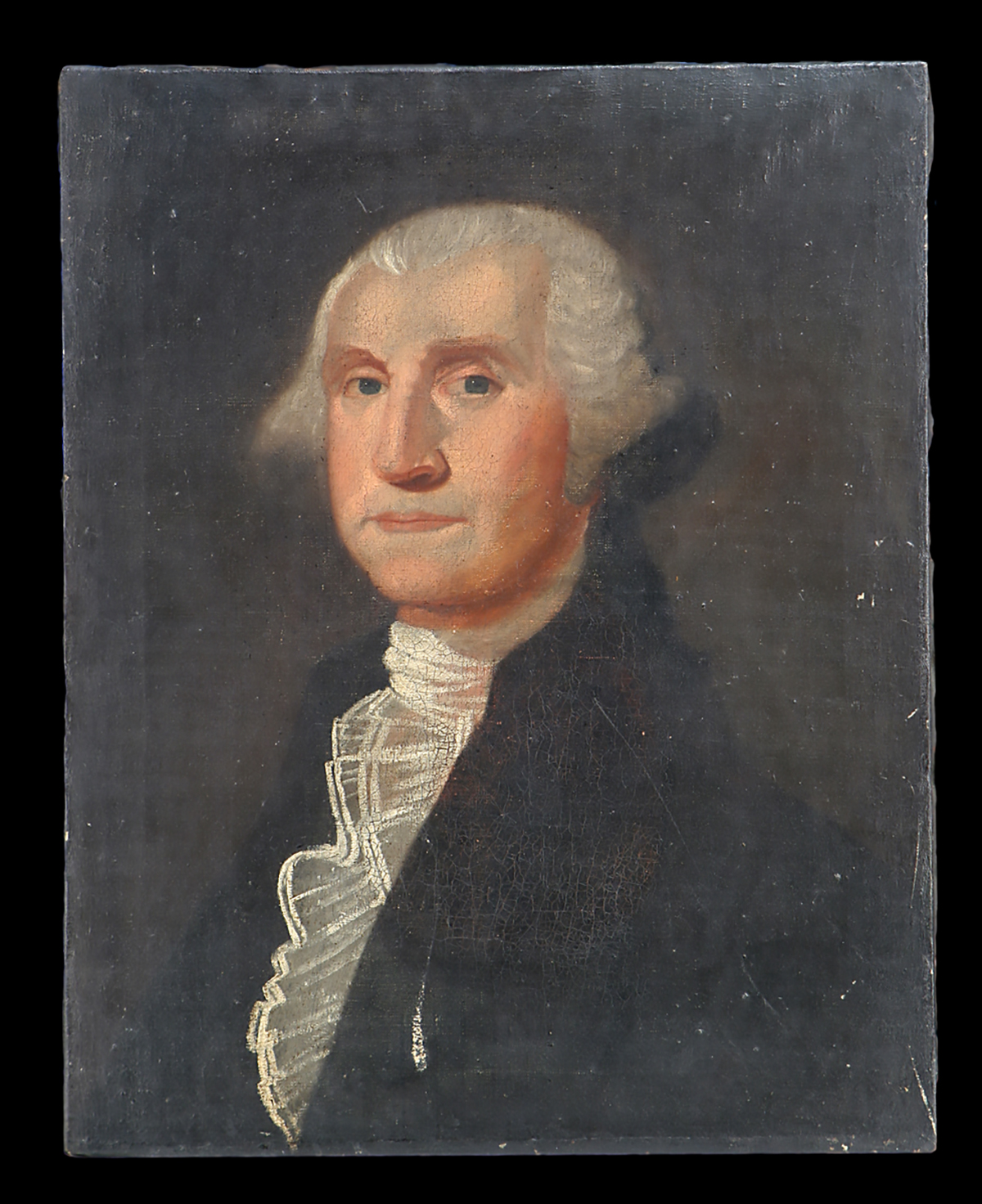

Portrait of George Washington (1800-1820). / THF8006

Heather Bruegl (Oneida/Stockbridge-Munsee) is the curator of political and civic engagement at The Henry Ford.