Dick Gutman: The Beckoning Diner Stool

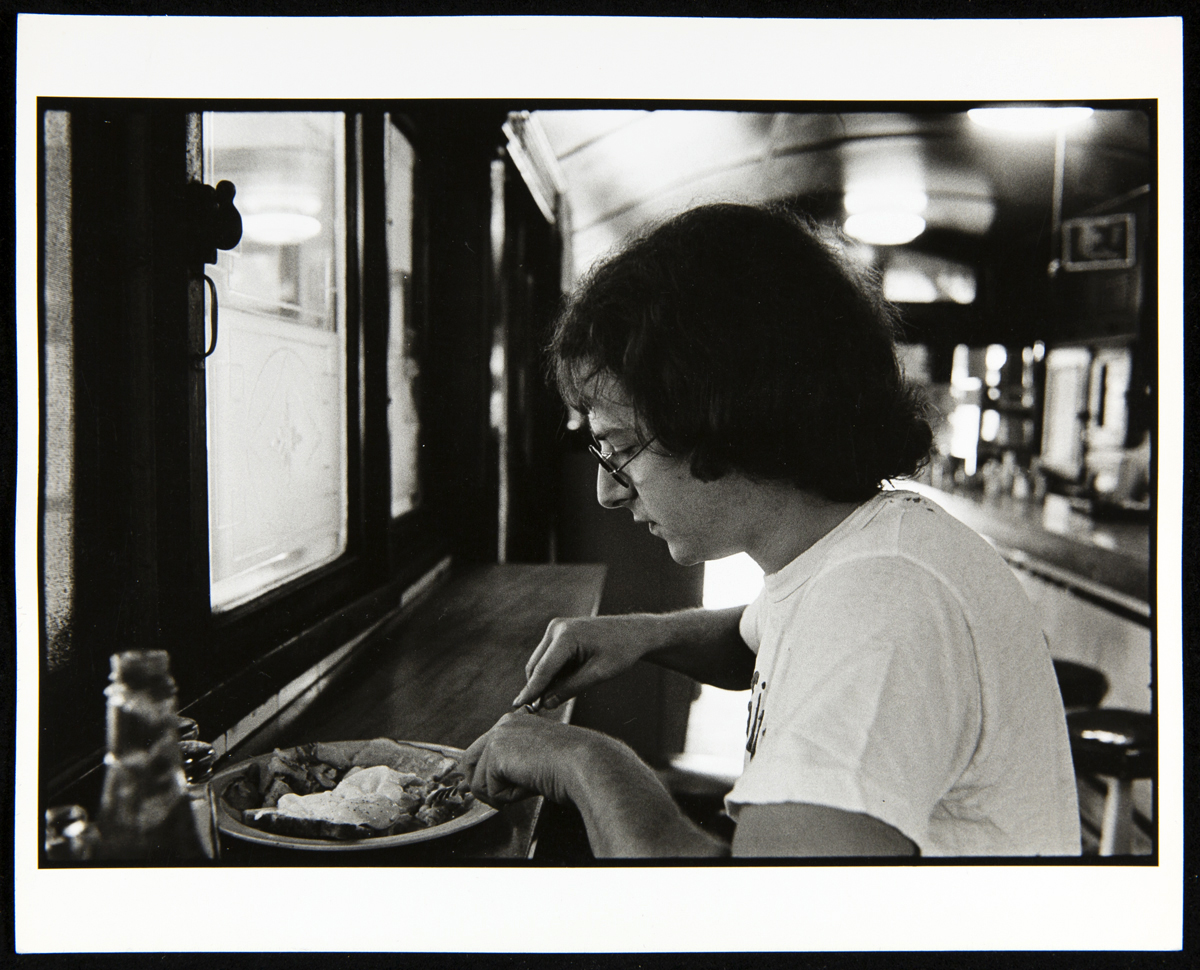

Richard J.S. Gutman in the Kichenette Diner, Cambridge, MA, circa 1974. Photograph by John Baeder. / THF297027

The diner, it seems, is irresistible. The sleek diner in a streetscape, the booth as setting for friends and family getting together, the beckoning counter stool for the lone traveler’s brief stop—all of it has become cherished over generations—the diner as a world within the greater landscape of people’s lives. For over half a century Richard J.S. “Dick” Gutman has been immersed in this world. He has spent his career living and breathing his way through the origins, design, operation, and stories connected to diners. Starting academically with his architecture thesis at Cornell University, his interests and efforts expanded and have continued to the present day through an active roster of publications, research, lectures, and restoration consultations.

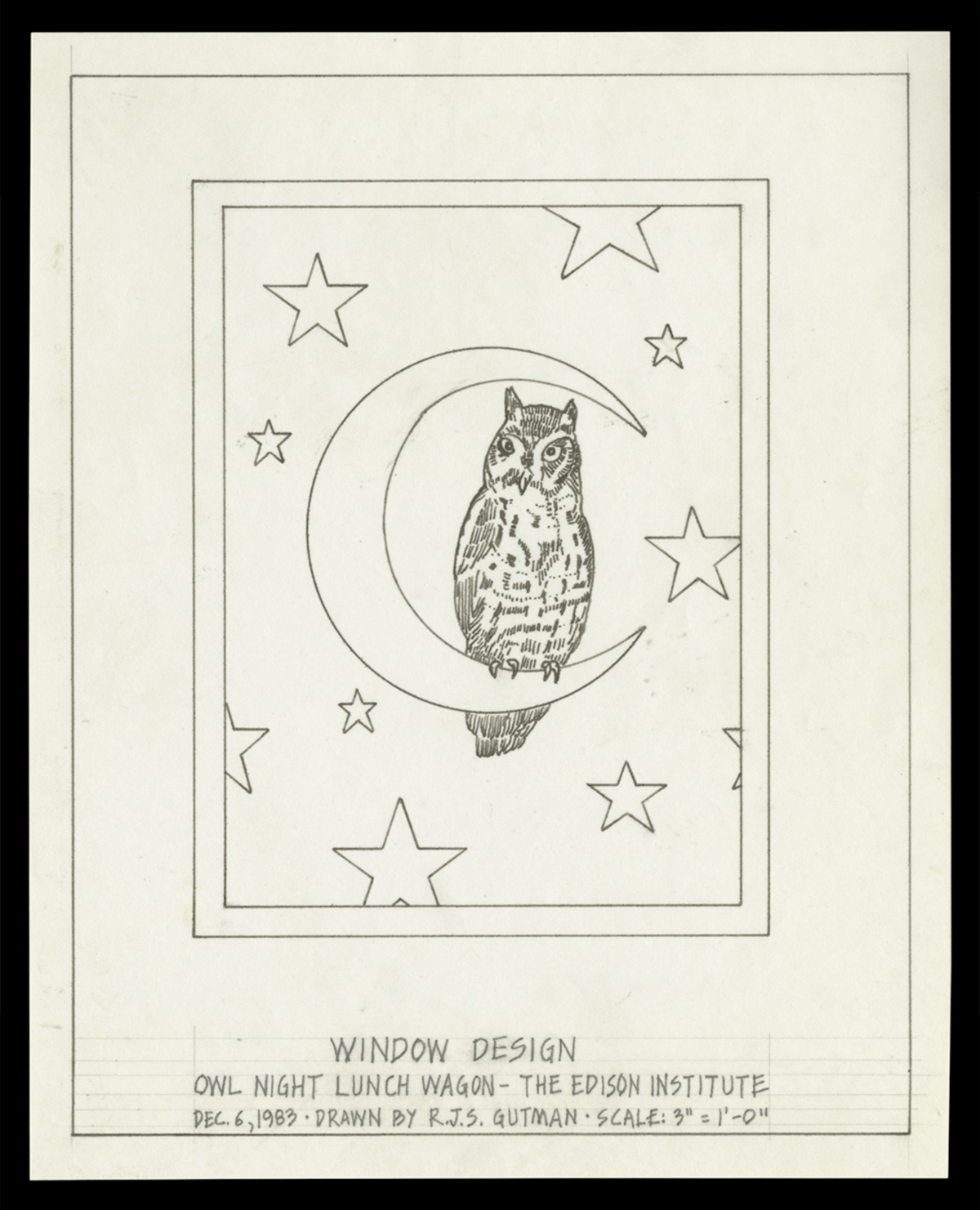

Window design drawn by Gutman during the restoration of the Owl Night Lunch Wagon, 1983. / THF715111

Much has already been “dished” about Gutman’s foundational years as an architectural historian specializing in American diners. Most recently, we were treated to a guest feature in The Henry Ford Magazine, penned by Mr. Gutman himself. Likewise, since the 1980s, he has worked as a consultant at The Henry Ford on guest-favorite projects such as the Owl Night Lunch restoration, the relocation of Lamy’s Diner, and collaborating to ensure the historical accuracy of Lamy’s menu.

In 2019, Mr. Gutman generously donated his diner collection to The Henry Ford. This collection includes everything from architectural fragments and interior fixtures to menus, trade magazines, historic photographs, and Gutman’s own photographic documentation. A rich and unmatched resource, co-curators Kristen Gallerneaux and Marc Greuther were honored to look deeply into this collection to create the temporary exhibit, Dick Gutman, DINERMAN (on view 25 May 2024 - 16 March 2025). A selection of the less-explored areas of this collection that are included in this exhibit are gathered here.

Dick Gutman, On the Road

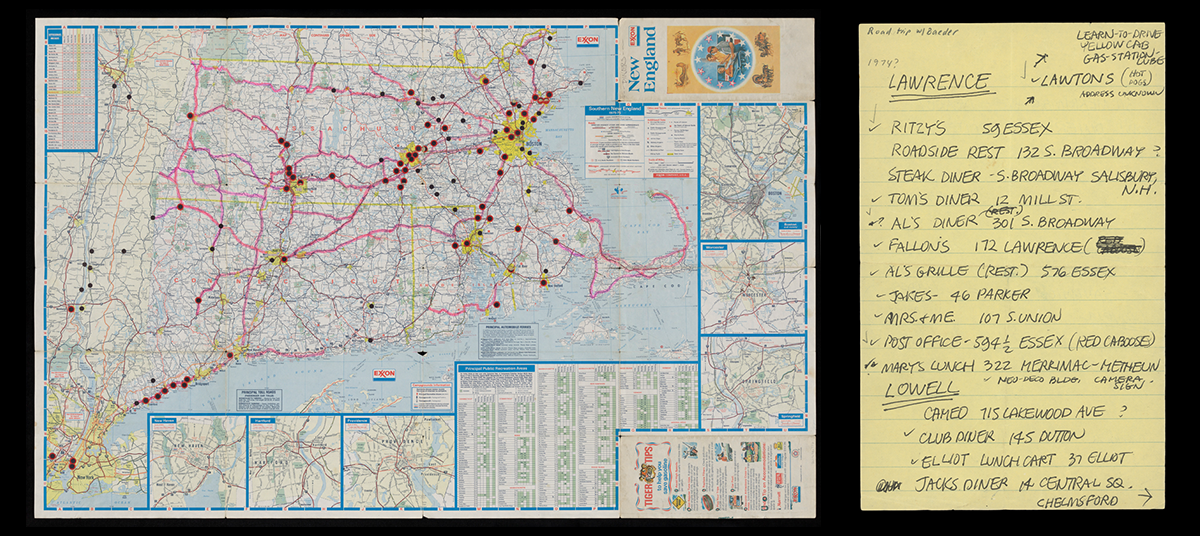

In 1975, when Gutman was 25 years old, he met Charles Gemme from the Worcester Lunch Car Company. Gemme—who was 95 at the time—wrote down a list of diners that Gutman should visit. Gutman hit the road with his camera. Typically he traveled alone but was sometimes accompanied by his wife Kellie or fellow diner-obsessive and painter John Baeder.

New England road map used by Dick Gutman with locations of diners indicated, circa 1975 (left) / THF715142; A diner list used during a 1974 road trip by Gutman & painter John Baeder (right) / THF714577

In an interview, Gutman described his challenges on these early trips: “Some [diner owners] didn't want to talk to me. They were too busy, they didn't understand it. They didn't like that my hair was too long. They thought I was from the health department.” But eventually, he began to break through: “I unearthed the history of diners by visiting and photographing them and talking to the people who owned them and the people who built them.”

The Fenway Flyer diner, as photographed by Dick Gutman in August 1971. This is the first photograph of a diner that Gutman took. / THF714873

Gutman’s collection contains an important “first,” in the form of a photograph. “The first diner I ever took a picture of was the Fenway Flyer. You have the slide, and it has a light leak. It's the first picture on my roll and I hadn't rolled the film in enough. I only took one picture like that, so it's timestamped in that manner. It was demolished around 1975.”

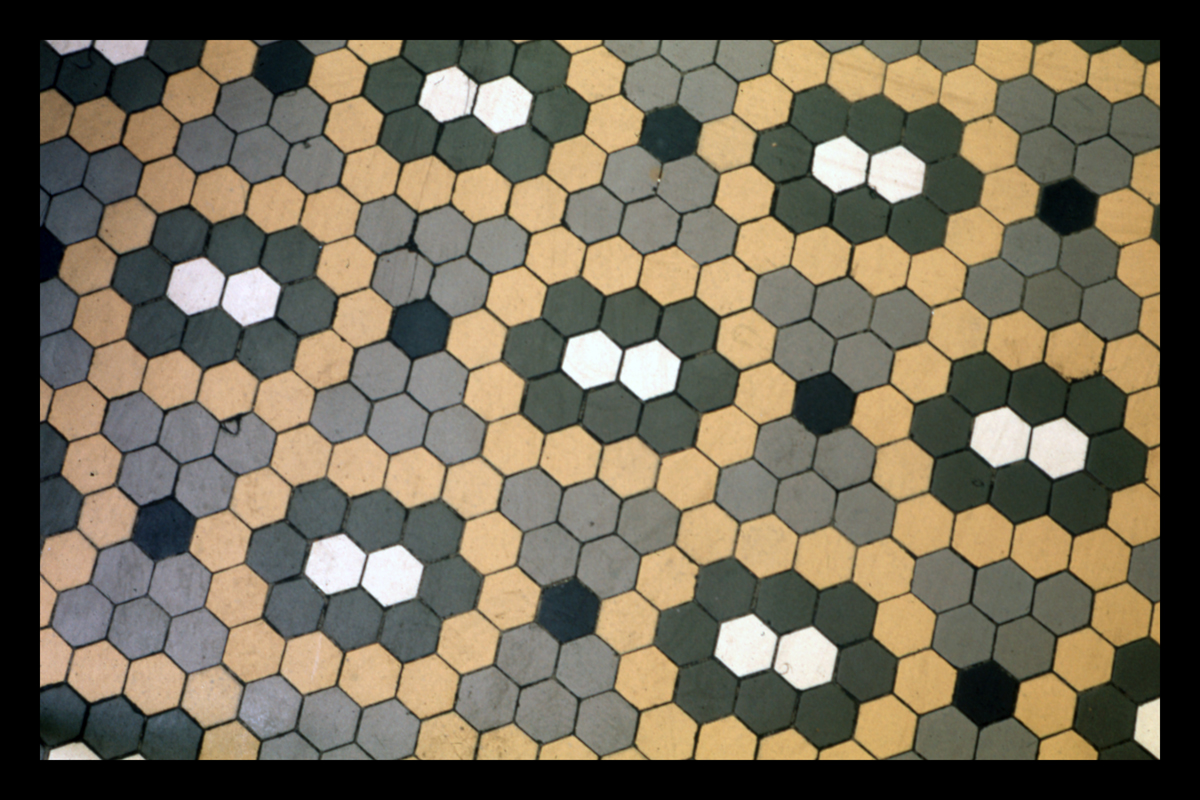

Gutman’s photographs of diners—largely concentrated in the 1970s through the early-2000s—are an invaluable time capsule planted at the intersection of unique architectural history, homegrown entrepreneurship, and community memory. They document the surface-level details of the type of visual flare that diners are known for: decorative tile, flashy steel and Formica-clad surfaces, and colorful, attention-seeking enamel signage.

Lettering on a porcelain enamel diner façade, Peerless Diner, later Four Sons Diner, Lowell, Massachusetts. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714788

Floor tile in Jimmy's Diner, Bloomfield, NJ. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714819

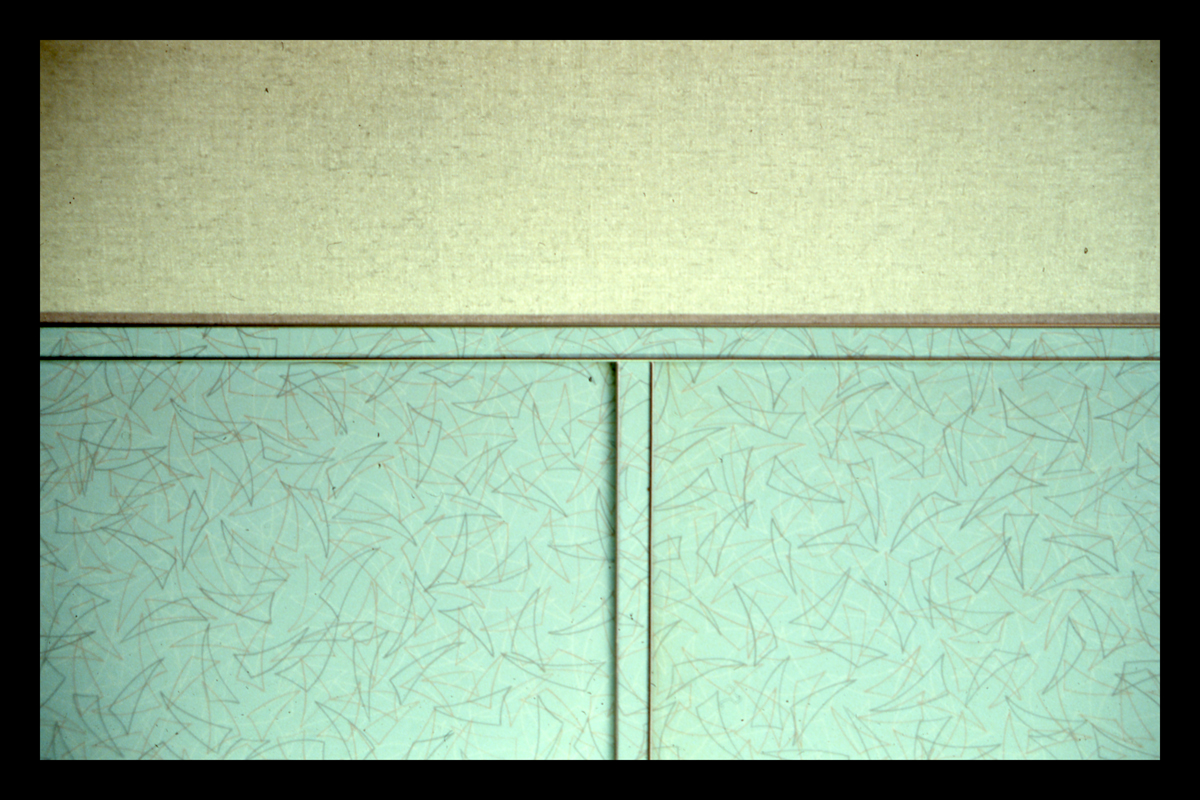

Formica at Deepwater Diner, Deepwater, NJ, 1987. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714808

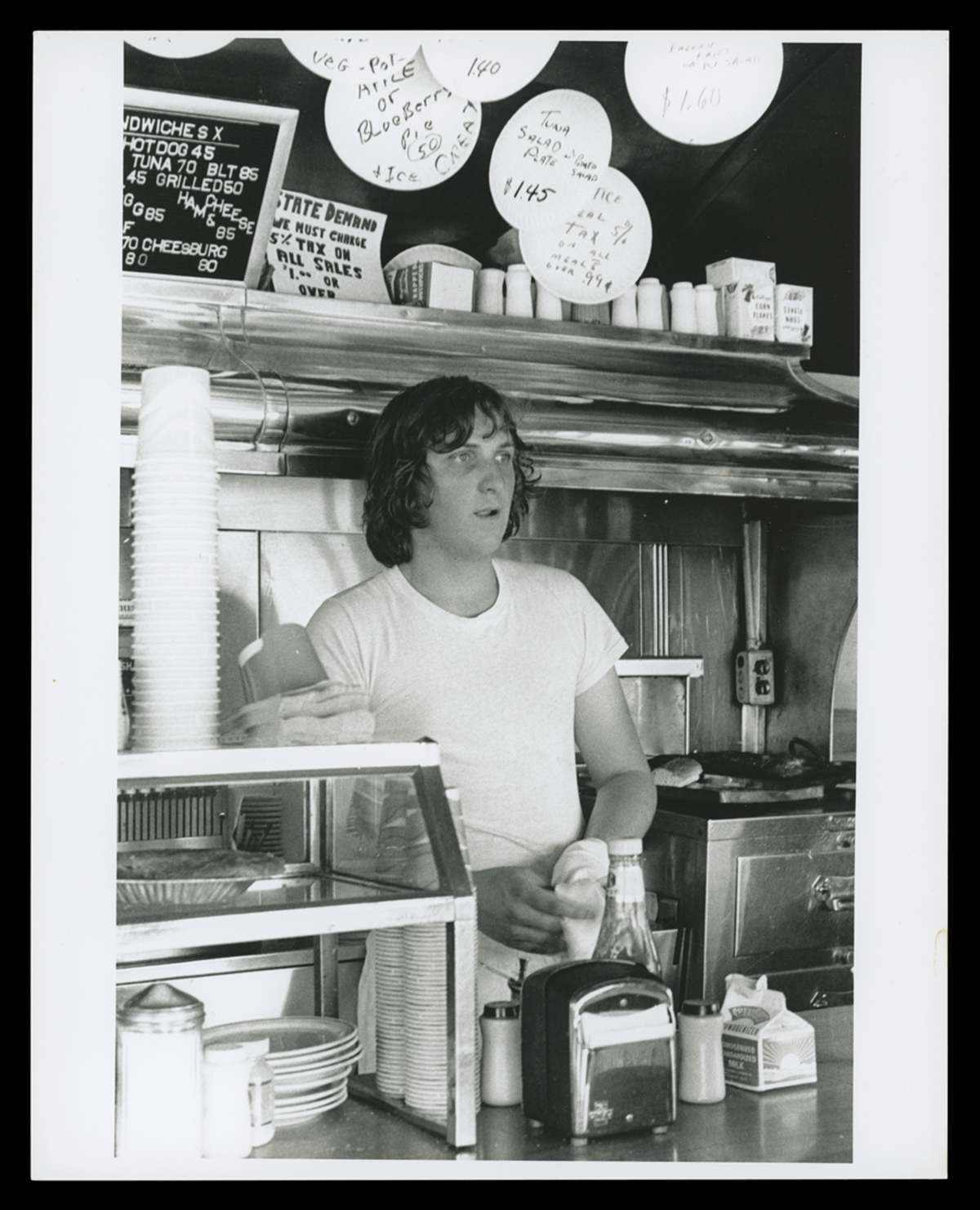

Notably, Gutman turned his camera to the details of interior spaces as well. He photographed employees moving through the nuanced workflows of confined diner spaces—spaces where everything was always on view. We see evolving uniforms, optimized grills, cluttered cashier’s booths, handmade menus, and shorthand orders scribbled on tickets. While Gutman’s collection contains a Wunderkammer’s-worth of disposable goods—paper coffee cups, toothpicks, serve ware, and paper hats—it is within these images where we are given a glimpse of these items situated within the “diner in action.”

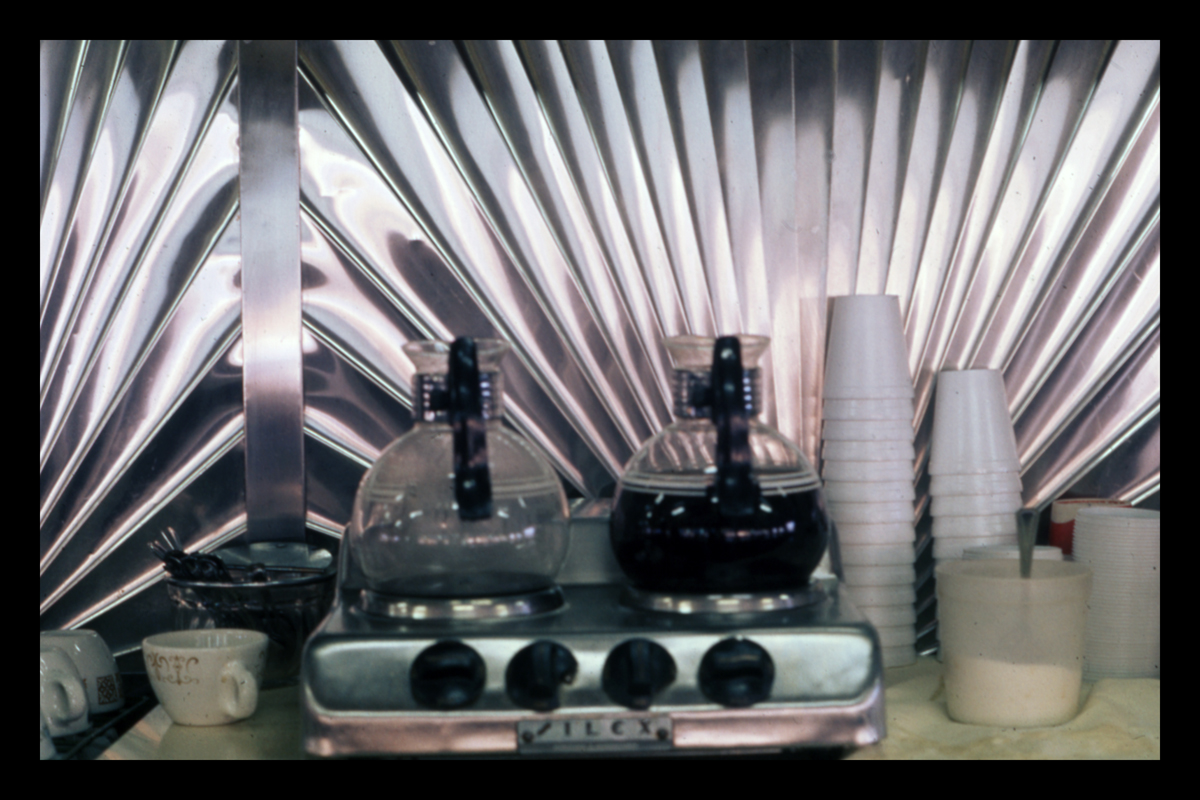

Coffee pots in front backbar clad in sunburst stainless steel panels, Phillips Diner, Woodbury, CT. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714795

Cook Kenny Barrett inside Buddy's Truck Stop, Somerville, MA, circa 1974. Note the handwritten specials on paper plates. / THF715018

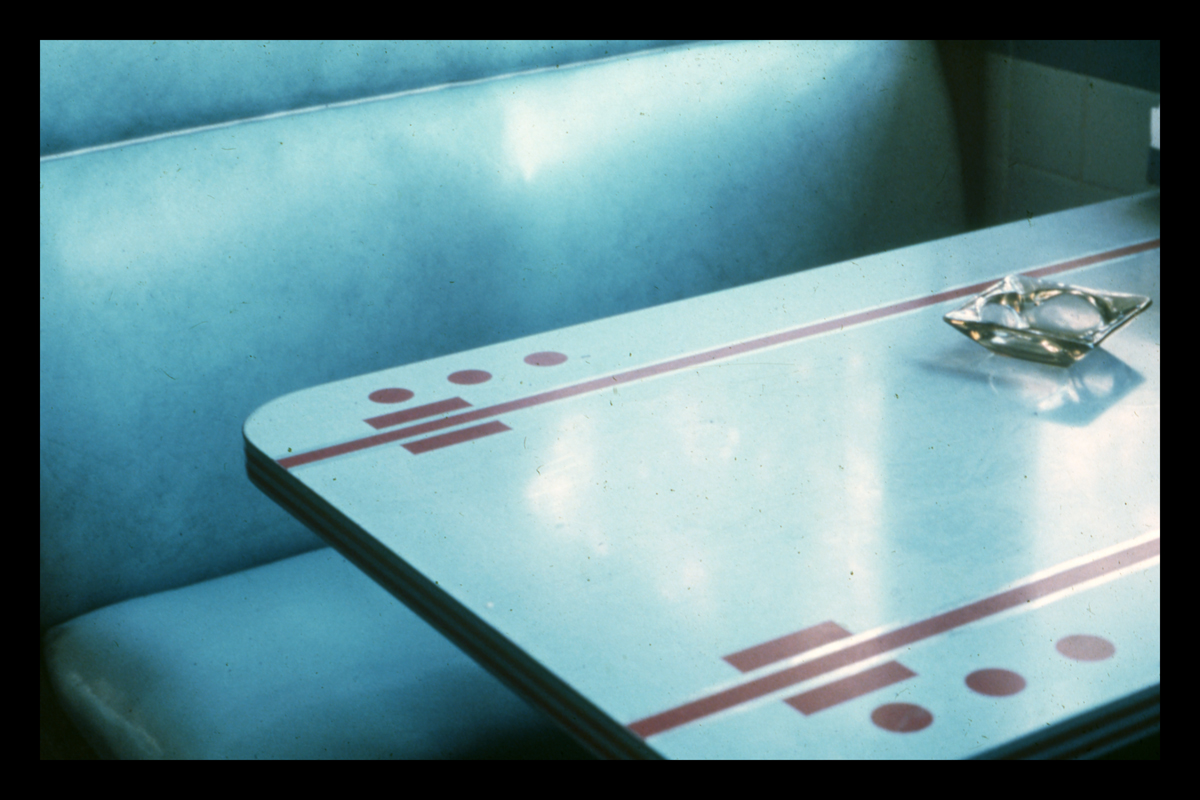

Less acknowledged in these images—but of great significance—is Gutman’s use of the camera to hint at those most elusive of sensory memories connected to the diner: a sun-drenched ashtray on a table that you can almost smell, vinyl-covered stools that stick to the back of your legs in the summer, the intense concentration of waitstaff leaning in to hear your order, the sizzle of the flat top grill cutting through the din of conversations, a sleeping baby on a booth table—oblivious to it all (or perhaps dreaming of diners). Enigmatic and unpretentious at once, these fleeting moments of the everyday that fill Gutman’s photography portfolio throughout the 1970s-1990s are deserving of our attention.

Booth in Village Square Diner, Grand Gorge, New York, 1973. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714814

Original 1938 porcelain enamel stools in Silver Top Diner, Providence, RI, 1973. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714811

Server taking orders at Collin's Diner, North Canaan, CT, 1972. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714846

Customers seated in a booth at Collin's Diner, North Canaan, CT, March 1973. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714844

Diner Archeology

As Gutman quickly learned, diners were on the decline. He realized that his first visit to a diner might turn out to be the last. All too often, he would return to a business after a short time to find the windows boarded over with for sale signs. Even worse, there were the times when he would find himself staring at a rubble-filled lot—the building demolished.

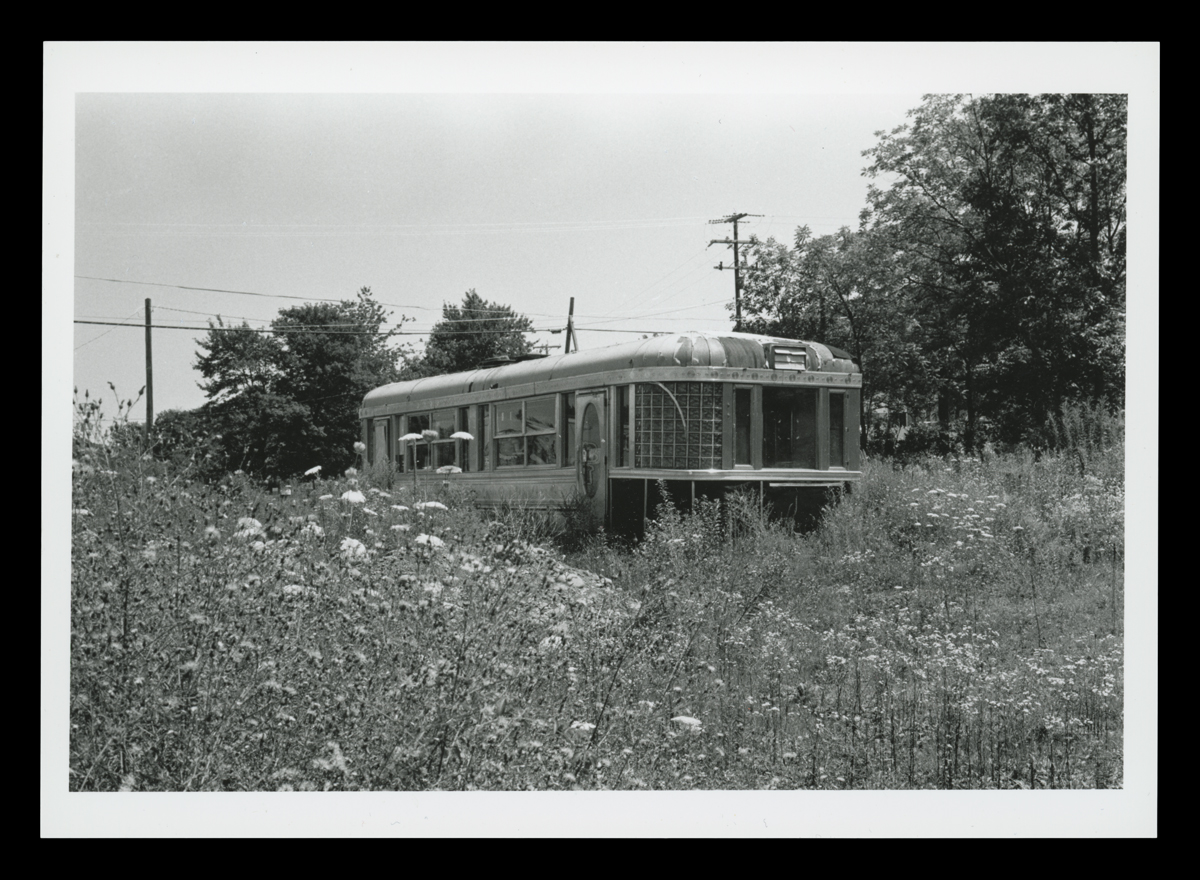

The former "Uncle Wally's," a 1950 Paramount Roadking model diner in a field, circa 1975. / THF714969

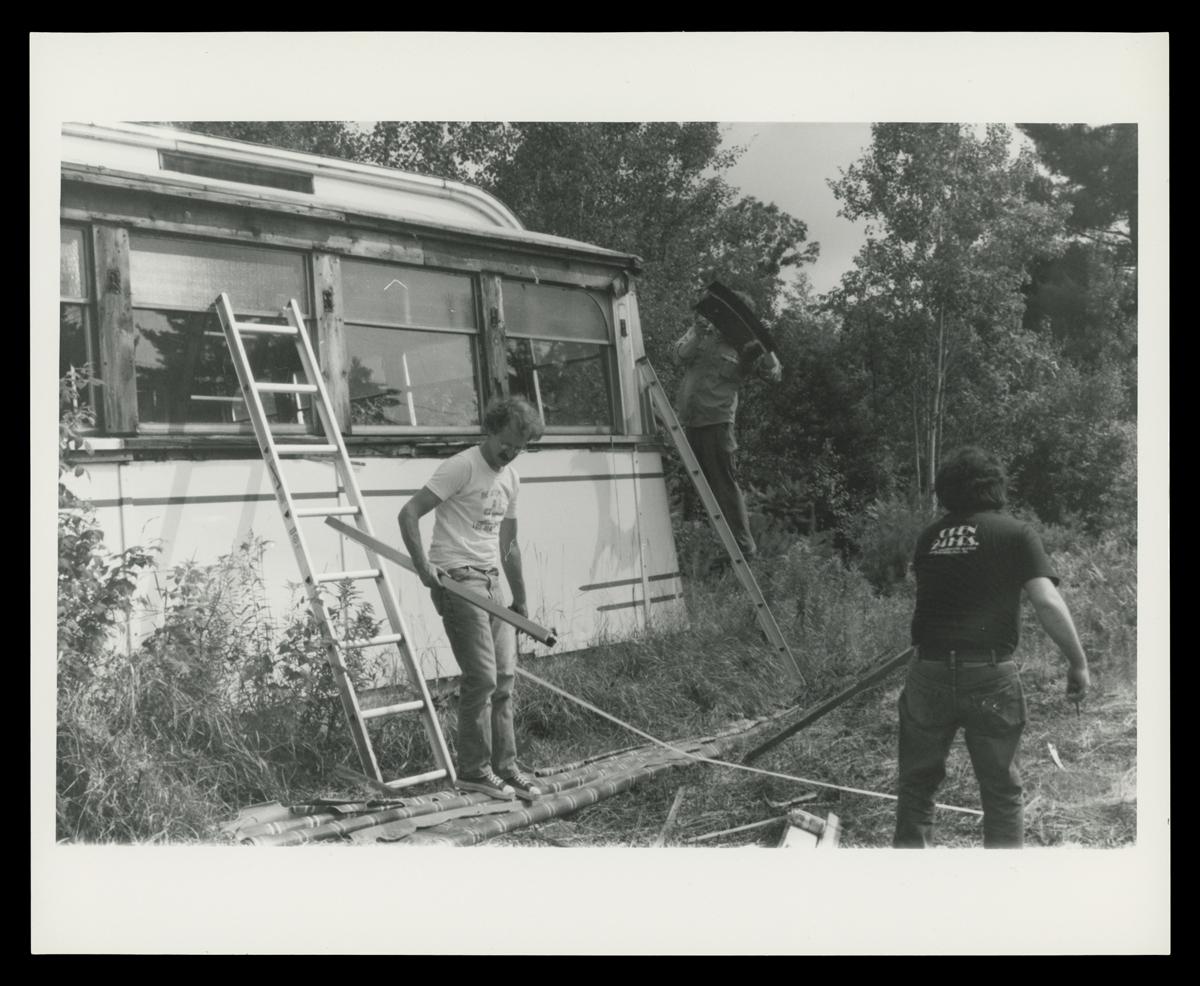

Richard Gutman (left) and Larry Cultrera Dismantling Corriveau's Diner for salvage, Gilmanton, NH, August 1985. / THF715129

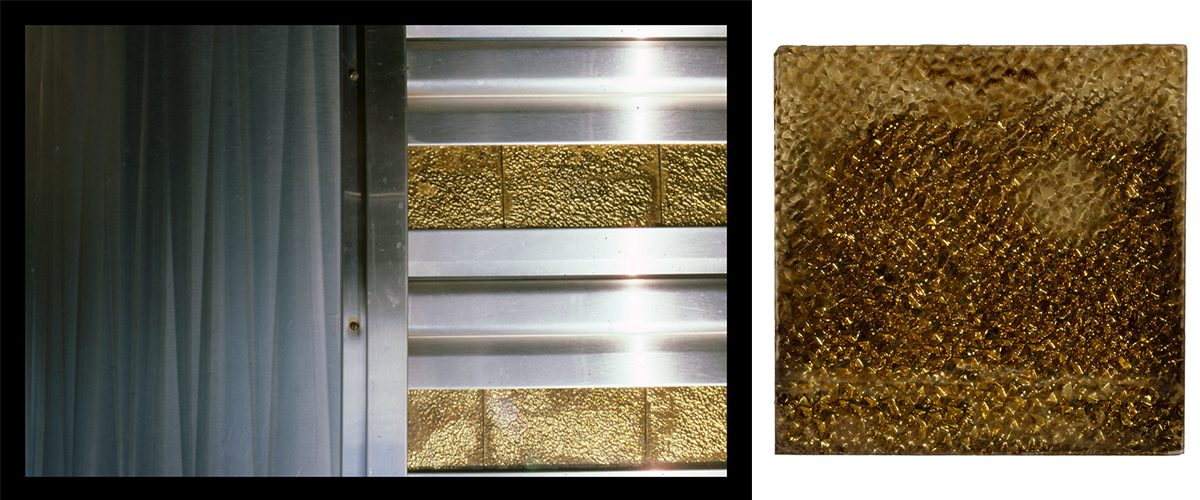

These experiences led to Gutman’s impulse to begin salvaging literal fragments of diners: chunks of tile floor lovingly laid by hand generations prior, a craggy section of Formica bearing the iconic pink “Skylark” pattern, and sparkling jewel-toned Flexglass tiles. They formed an essential reference library for Gutman’s restorations, providing physical proof of surprising trends in materials, interior designs, color, and patterns that filled diners.

"Skylark” pattern Formica fragment, from the Americana Diner, 1952-1953. / THF371317

Flexglass and stainless steel cladding on Key City Diner, Phillipsburg, NJ (left) / THF714804; Flexglass tile from the Lincoln Diner, Kensington, CT, circa 1960 (right) / THF371079

Sometimes, Gutman received news of a diner closing and was able to work directly with its owners to recover decorative panels, menu boards, and historic counter stools. During these salvage operations, he was careful to document where even the tiniest shards originated, which—over decades of collecting—might be reunited with additional ephemera from the same diner. While some may find this type of collecting strange, Gutman extracted these fragments of the past from the field as a way of preserving the future.

Gutman noted in a recent interview: “One of the great tile finds was in Rhode Island. I was photographing Snoopy's Diner and I had to go across the road to get the picture. […] I'm carefully backing up to make sure that I don't fall down the hill. And I look, and there's the remains of another diner. Instead of hauling it away, they just bulldozed the thing! A lot of it had rotted, but there were still the indestructible ceramic tile walls and floor—which I picked up some massive pieces of and put in our car. They're now part of [The Henry Ford’s] collection. Not exactly like Pompeii or Herculaneum—but they have a story to tell.”

Wall tile fragment mentioned above, from the site of a Worcester Lunch Car in North Kingstown, RI, 1920-1939 (left) / THF197842; Floor tile fragment from Hodgin's Diner, York Beach, ME, circa 1915 (right) / THF197841

Beyond their importance within the built environment, diners have impacted our culture, communities, and of course foodways at a national scale. During a time when the American diner seemed to be rapidly disappearing, Dick Gutman raced to document this landscape. This undertaking was crucial to preserving and raising awareness of these easily-lost commercial forms of architecture. We at The Henry Ford are grateful to act as the repository for the incredibly prolific tapestry of research, images, and objects that Dick Gutman gathered.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communication & Information Technology. This blog excerpts and expands upon exhibit labels written by Kristen Gallerneaux and Marc Greuther, co-curators of Dick Gutman, DINERMAN.