Dishing on Diners

The world’s expert on diners shares his start, describes his discoveries and explains his connection to The Henry Ford.

By Richard J.S. Gutman

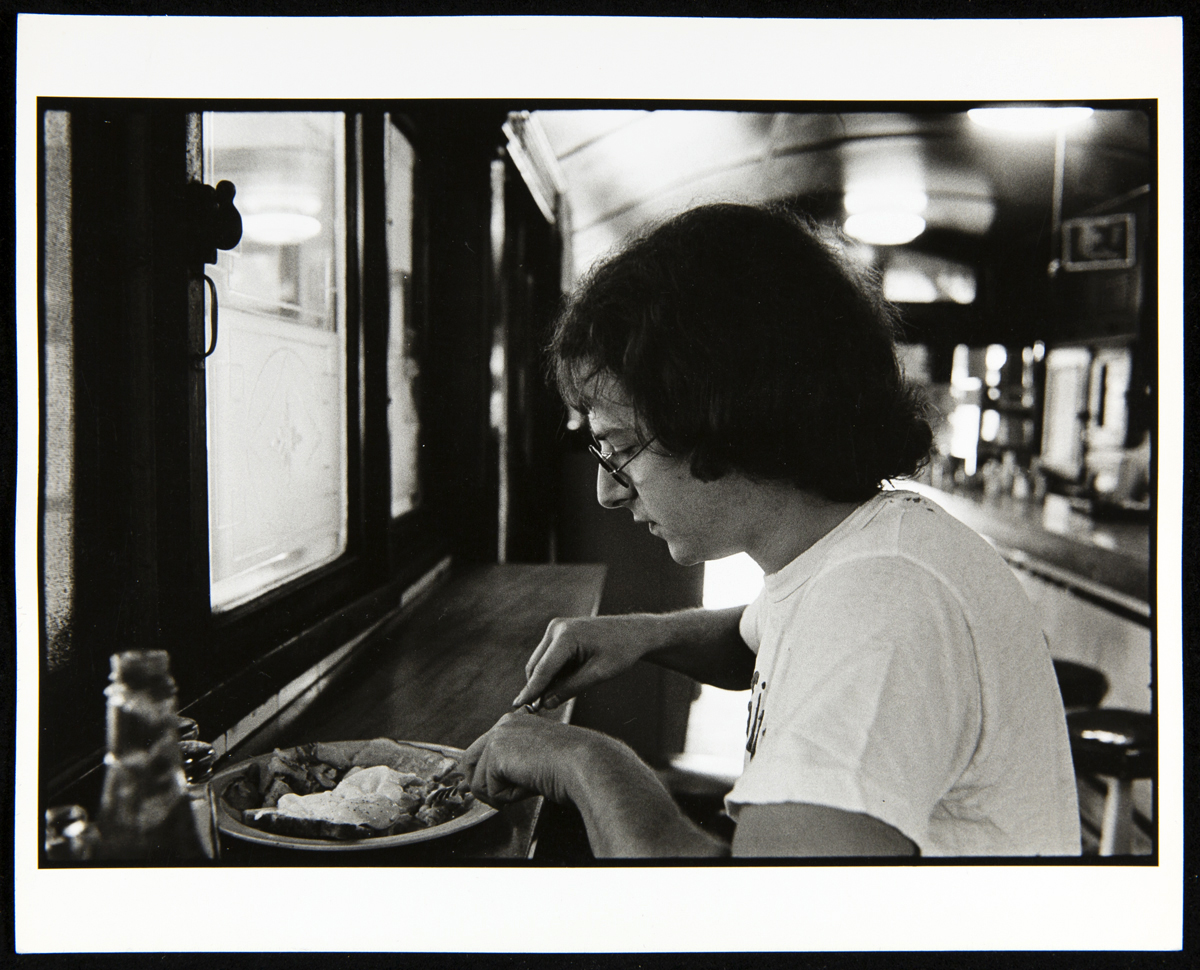

My half-century immersion in the world of diners began with poached eggs on toast in the middle of the night at Bud’s Diner, hard by the railroad tracks, in Ithaca, New York. It was 1970, and I was on a break with classmates from an all-nighter at Cornell University’s School of Architecture. Seeking sustenance, I substituted a swiveling stool at the counter for an equally uncomfortable drafting stool up on the Arts Quad.

Photo by John Baeder

An authentic diner — a long, low structure built in a factory and hauled to a site equipped with cooking equipment, dishes and silverware — is a particular type of informal lunch counter restaurant, which in its heyday during the 20th century frequently appeared to be like an immobile railroad car, but a resemblance was the only connection to a train.

Diners had been one of my family’s go-to restaurant options in the 1950s and ‘60s in Allentown, Pennsylvania. There were four within walking distance of our house near the town’s fairgrounds and 22 in and around the All-American City of 100,000 at the time.

When I was a youngster, I was unaware of the unique design and architecture of diners. We just went there for a good meal. When I was at Cornell, though, we had a rotating crew of British design critics visiting. Eating in diners was their eureka moment, having never experienced one before. Seeing diners through their eyes sparked my interest.

For my Bachelor of Architecture, I proposed a thesis on the diner as an archetypical manifestation of vernacular design: a clearly defined prefabricated fast-food outlet that was the product of self-taught designers and craftspeople. I planned to document the changing styles of the roadside diner over its 100-year history. In New England and the Mid-Atlantic, ubiquitous gleaming stainless steel and porcelain enamel buildings beckoned customers with their glowing neon signs. Yet these incredible places had no written history of their 100-year past. There was no book written about diners, just the occasional newspaper story and article in a popular magazine.

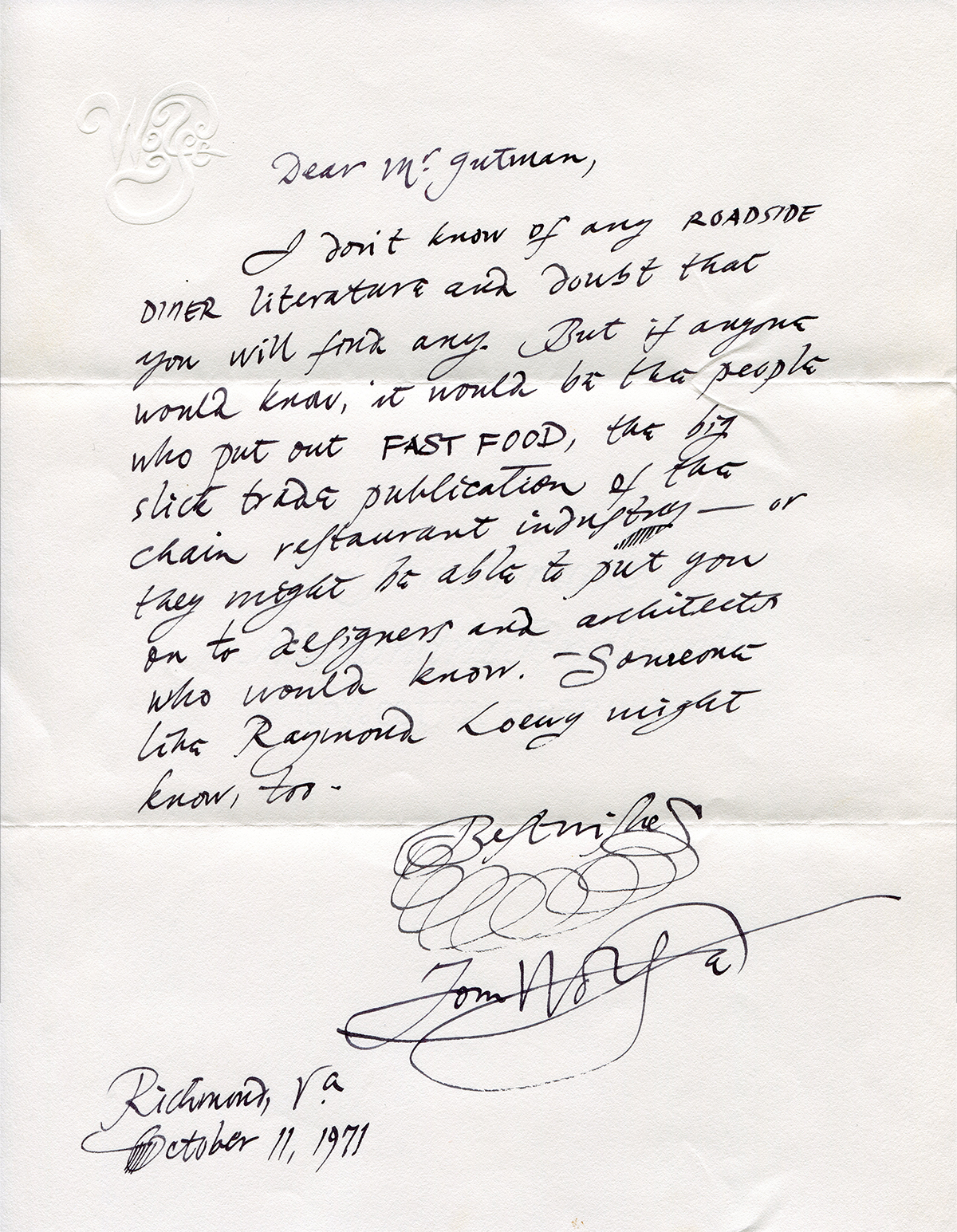

As I began to scratch the surface of the subject, I sought inspiration from a few noted observers of American life. It was a red-letter day when I received a handwritten note in return from American author Tom Wolfe; his suggestion to seek out trade publications from the fast-food industry led me down a road that I am still following.

Photo courtesty of Richard Gutman

Wolfe examined and elaborated on aspects of pop society that others hadn’t noticed or were deemed too insignificant to ponder, namely California custom cars, in his book The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby. Following Wolfe’s advice, I discovered the existence of The Diner magazine, a monthly publication devoted to “the dining car world,” launched in 1940 and ending its run in December 1959.

I learned that the John Crerar Library, then at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, had extensive holdings of The Diner. Over Christmas break in 1971, I traveled there for an in-person look. It turned out that the magazines had been slated for deaccession and were awaiting disposal. The librarian at Cornell arranged to acquire them, and they ended up with me, forming the core of my collection. They remain an invaluable contemporary window into the diner world of the midcentury, and I could literally find something new to me each time I picked one up.

I soon learned that this business could be traced to a handful of family enterprises that began in the 19th century, manufacturing mobile lunch wagons at first and then expanding into larger permanent, yet movable, buildings constructed in factories.

Visit by Visit

I unearthed the history of diners by visiting and photographing them and talking to the people who owned them and the people who built them. The buildings are uniquely American but were mostly conceived and constructed by immigrant craftspeople or first-generation Americans. Irishmen like Patrick J. Tierney and Jeremiah O’Mahony were preeminent in metropolitan New York. French Canadians formed most of the workforce of the Worcester Lunch Car Company of Massachusetts. German sheet-metal workers and Italian tile setters and cabinetmakers combined their talents to form the melting pot inside the factories that produced these quintessential eating places.

In a 1932 article, Jerry O’Mahony asked “Who Runs These Dining Cars?” as part of a sales promotion. A survey revealed that this community of entrepreneurs had switched careers from a wide range of jobs: bus drivers and bond brokers, clerks and college professors, bookkeepers and salespersons, housewives, and service station and garage workers as well as hoteliers and restaurant workers.

Greeks first got a toehold behind the counter of diners in the 1920s. James Georgenes bought his first restaurant from the Worcester Lunch Car Company, and by 1936, he and his brothers, along with some friends and cousins, had a chain of five diners in the greater Boston area. Over time, many Greek families entered the diner business, often starting as dishwashers and working their way up to ownership.

Many of the owners I got to know shared their stories and gave me old snapshots, matchbooks, menus, placemats and postcards, which they used for advertising but which also helped me to construct a timeline of the diner industry.

One of the first postcards in my collection, published in 1938, was of customers standing at the takeout window of the “Night Owl Lunch, Greenfield Village, Dearborn, Michigan.” I knew I had to see this in person — if it still existed — and when I gave a diner lecture at Lawrence Technological University in Southfield, Michigan, I did so. (See sidebar on Page 52.)

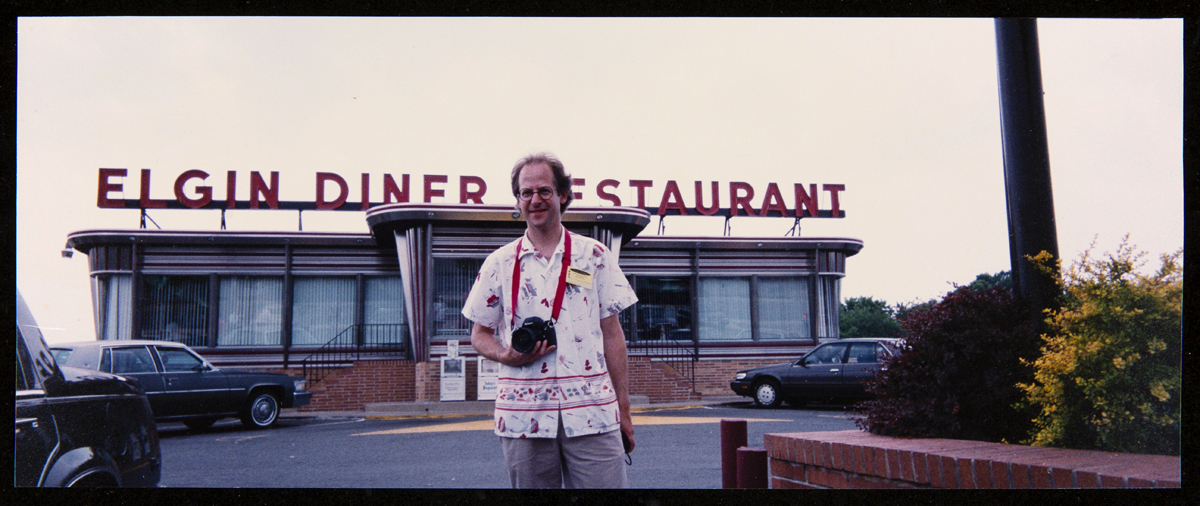

In 1979, my first book, American Diner, was published. This was followed over the years with three others, including the only book ever written about one diner company: The Worcester Lunch Car Company. Along with the books came lectures, restoration projects, museum exhibitions and new diner consultations. As the Chicago Tribune quipped in 1993 when I was on tour with my second book, “Richard J.S. Gutman led a fairly normal life. Then he discovered diners.”

At the Counter

It’s been said that everyone feels welcome at a diner; it’s the most democratic of places. But this wasn’t always the case. The clientele of diners has changed over time.

Photo by KMS Photography

The earliest night lunch wagons catered to the working class, mostly men. Word-of-mouth regarding the tasty, affordable chow started to entice women office workers as customers. As the mix at the counter expanded to include everyone and diners advertised “Tables for Ladies,” it was said that “Men and women in evening dress swap jokes with men in overalls,” in an observation in The New York Times Magazine on Oct. 19, 1941.

In one rare instance, a young waitress captured the customers over and over in a series of more than 200 snapshots. Joan Hepner started working at the Pole Tavern Diner at Pittsgrove Circle in Salem County, New Jersey, when she was a junior in high school in 1952. Four years later, she married Smoky Wentzell, the owner.

One day, Joan brought her camera to work, leaving it at arm’s length on a shelf behind the counter. When friends and regulars came by, she would snap their pictures. Farm families, local business people and state police packed the place. Groups of kids hung out after school or after the auto races at the nearby Alcyon Speedway, which also hosted their high school football games, boxing and wrestling matches, and semipro baseball.

The Pole Tavern Diner was a scheduled stop for the Baltimore-Atlantic City bus route on Route 40. Passengers, and people in their cars headed to and from the shore, filled the diner regularly throughout the year, and Joan caught much of the action.

Changing Landscape

The diner business has had its ups and downs as changing tastes and competition became forces to reckon with. More families ate in diners after World War II as the baby boom generation came of age in a more affluent society. At the same time, fast-food chains began to muscle in to the restaurant roadside, and this pushed the diner into uncharted territory design-wise and led to a broadening and expansion of the food offerings.

Diners grew in size, added dining rooms to accommodate larger groups and outgrew the “vehicle look” that had been standard for nearly a century. After experimentation with a futuristic image, the builders turned to colonial and historic revival styles that were a radical break from the norm.

Even though the look of the diner shifted over the years, the idea of good food, fairly priced, in a friendly environment remains a constant. Simply put, diners serve the food people want to eat.

Some favorite places are lost each year for a variety of reasons, including aging out of the operators, lack of family interest in continuing the business, real estate pressures and, most recently, the pandemic. When a diner goes out of business, we lose an interesting building, a community gathering place and an entrepreneur’s struggle to succeed.

From the Henry Ford Archive of American Innovation

Final Thoughts

In 2005, I spotted the always-recognizable Tom Wolfe at a collegiate squash tournament at Harvard, where his son was playing for Trinity College’s perennially winning team. I approached him and introduced myself, saying I wanted to thank him for the good advice he gave me more than three decades earlier. He did not recall the content of his letter but did remember his stationery with “Wolfe” in a psychedelic interpretation embossed on it.

I anticipated that he might be standoffish — he was anything but, with an “incongruously gracious off-page persona,” as mentioned in a New York Times review of the recent film documentary Radical Wolfe. We conversed for 20 minutes about diners and roadside vernacular, among other things.

With four diner books under my belt, and having acquired the moniker “the world’s expert on diners,” I felt meeting Wolfe in person was a wonderfully serendipitous and gratifying encounter with the mythical figure I had always credited with giving me my start.