Everyday Jim Crow

Before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, America was legally ruled by segregation—the separation of citizens based on race and ethnicity. These laws, both formally written into law and local, societal norms, often were based on the historic Black Codes (or Code Noire in French-speaking Louisiana), which dictated how African Americans were to interact with whites: from where one was able to buy a house or allowed to live generally, to stepping off the curb when passing whites on the sidewalk. These laws became known colloquially as “Jim Crow” laws.

An interesting artifact in the collection of The Henry Ford is a “Jim Crow” cookie cutter (circa 1840-1870) dating from the earliest years of transition in forms of racial oppression / THF169389

Who Was Jim Crow?

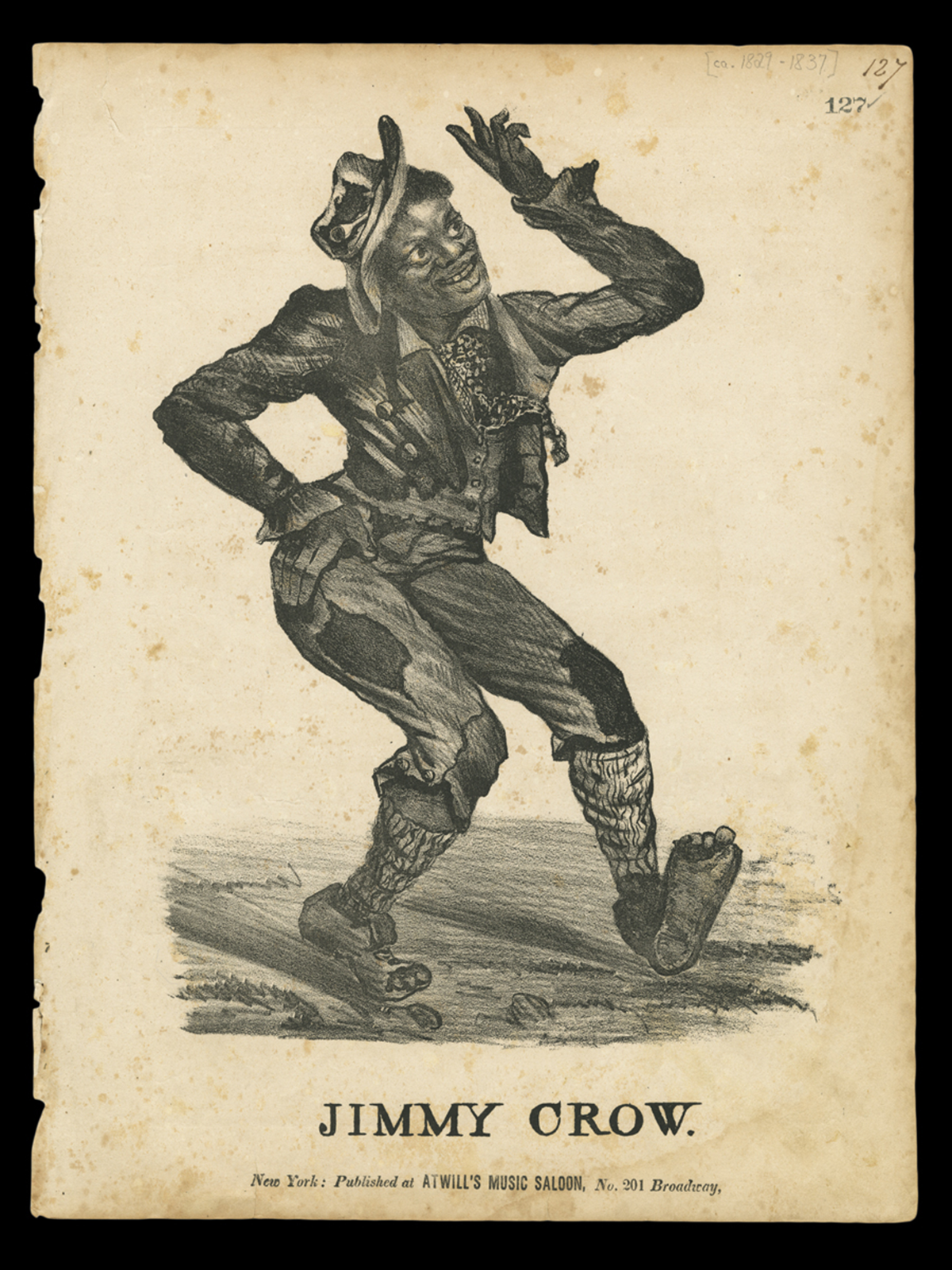

He was a folk character popularized by white minstrel performer Thomas D. Rice and popularized in 1828. Jim Crow laws, put in place by local and state governments across the country, enforced racial segregation in public spaces and life. Stereotypes were popular ways of maintaining and promoting racial hierarchies and spreading distrust of “The Other” within white U.S. society. The Jim Crow stereotype became a popular form of not only diminishing African American cultural practices and physical differences to people of European descent but also normalizing thinking of them as lesser people.

The most sinister aspect of Jim Crow was how embedded it was in the everyday life of every American. Given that the music of the time was established in the minstrel scene, it isn't surprising that songs were rife with references to Jim Crow, like the sheet music seen here.

Music Sheet, "Jimmy Crow," 1834-1837 / THF98689

Navigating These Spaces

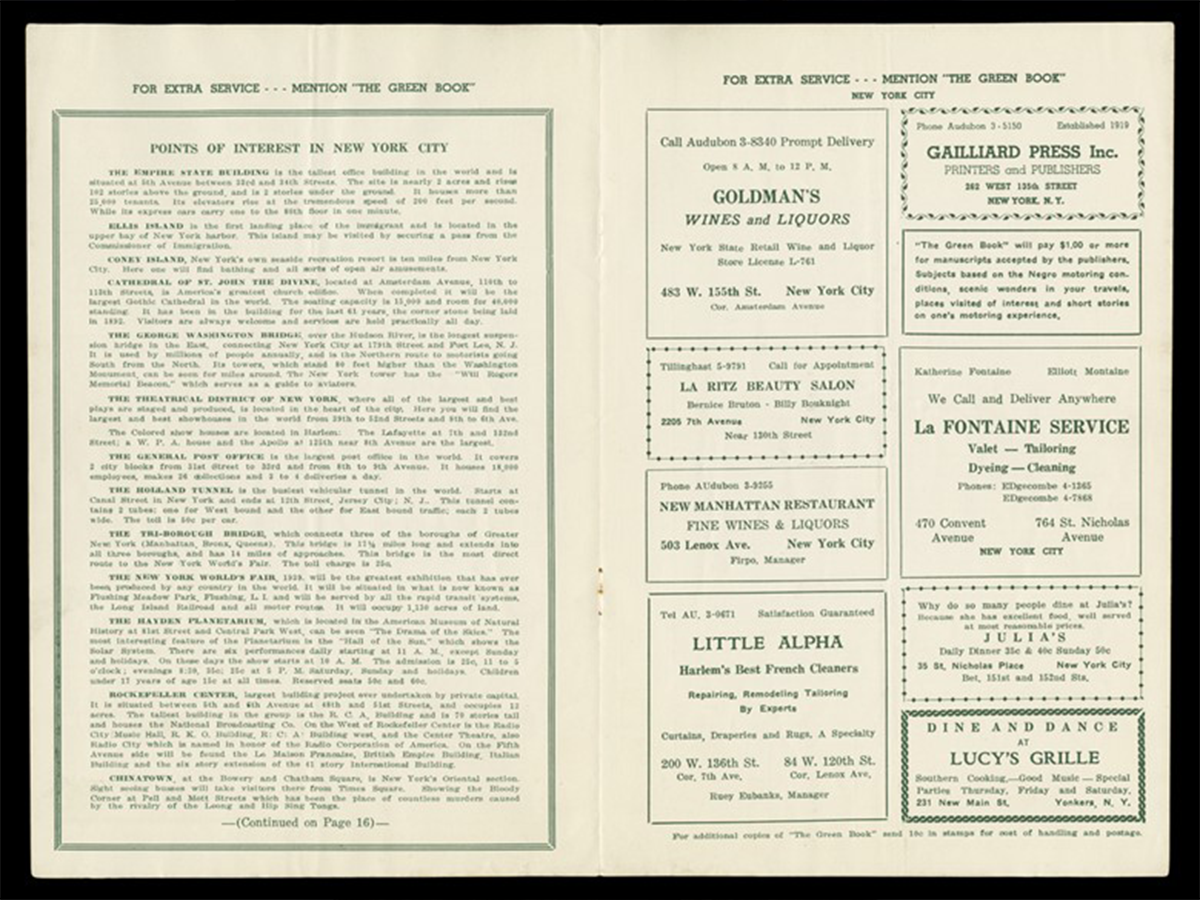

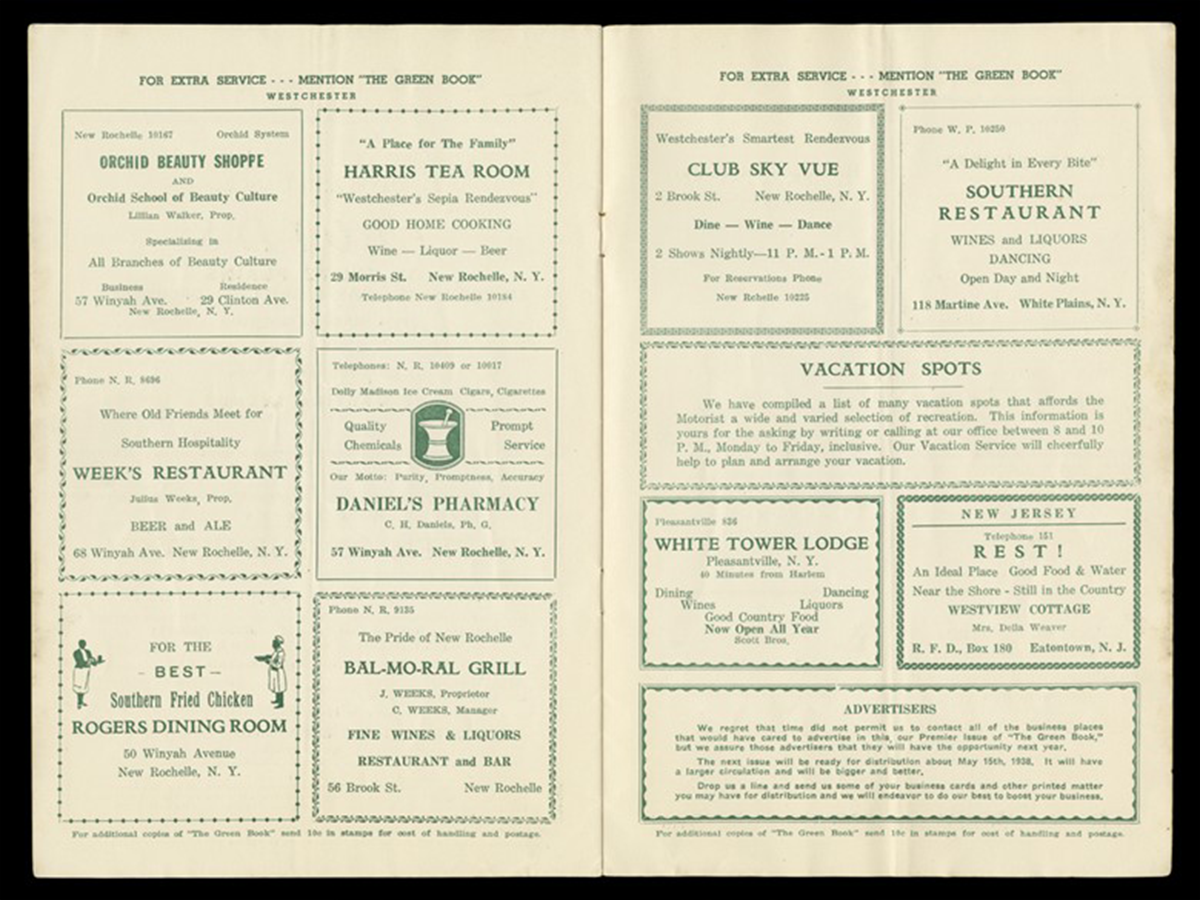

It is critical to note that African Americans did not take kindly to Jim Crow—the figure, or the laws. They consistently resisted, creating their own resources, businesses, and economic systems within their own communities. One of the most important tools used by African Americans to navigate, literally and figuratively, was The Negro Motorist Green Book. Published between 1936 and 1966, the “Green Book” contained advertisements and details on hotels, restaurants, and other destinations that catered to Black visitors. The spaces were oases for Black travelers who could go hundreds of miles without safe places to stop and rest.

Guidebook, "Negro Motorist Green Book, 1937 Edition, Complimentary Issue", page 6-7 / THF99199

Guidebook, "Negro Motorist Green Book, 1937 Edition, Complimentary Issue", page 12-13 / THF99202

Fighting Back

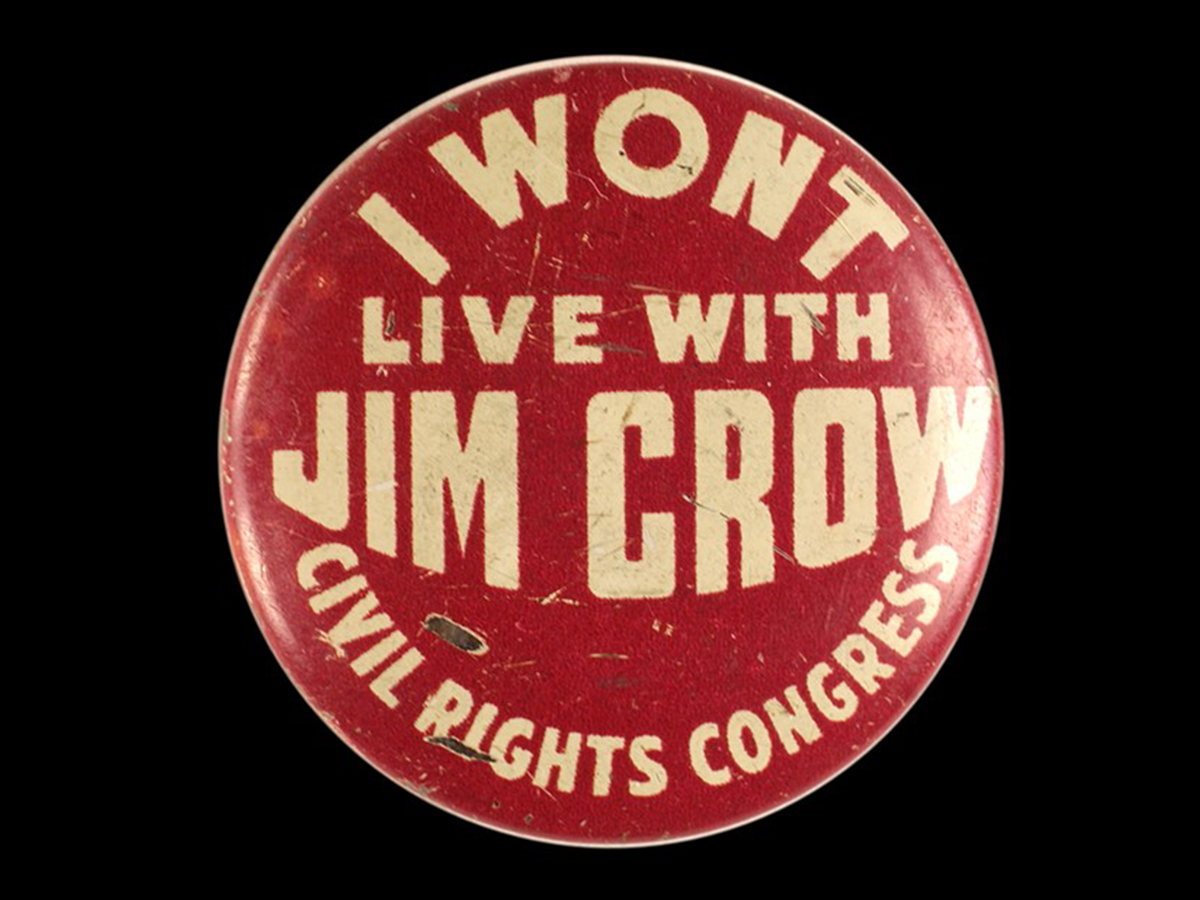

Combatting Jim Crow took organization from several different African American-led and allied groups. The oldest of these is the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, founded in 1909 when the premiere of The Clansman placed the Ku Klux Klan into a celebratory national light. The button below is from the Civil Rights Congress, a labor-based collaboration concerned about cases of racial injustice, particularly as it affected Black Americans in the South. These groups, working at the national and legal levels, often were supported by coalitions and individuals on the ground—who usually took the risks of violence head-on. Together, communities challenged the power of Jim Crow and chipped away at its power until they forced change everywhere.

“I Won’t Live with Jim Crow: Civil Rights Congress” button, circa 1948 / THF1619

Amber N. Mitchell is curator of black history at The Henry Ford.