Feeding Students / Students Feeding Themselves: School Gardens at The Henry Ford

Henry Ford Trade School students eating lunch, May 24, 1937 / THF626068

Feeding students. It sounds like a one-way street. Food arrives. Cooks prepare it. Students consume it. But evidence in The Henry Ford collections confirms that students played an active role in growing food, planning menus and preparing lunches. They assumed the responsibility for feeding themselves.

The following overview of student-food interactions confirms the central role that school gardens played in educating students about food. The German province of Schleswig-Holstein engaged teachers and students in hands-on, garden-based agricultural education as early as 1814. The Swedish parliament called on teachers to establish and maintain gardens with their students in 1842.

Students in the School Garden outside Public School 65, Brooklyn, New York, 1890-1915 / THF38044

Others advocated for school gardens too. Medical professionals believed that working outside helped reduce the likelihood of students contracting contagious diseases like tuberculosis. Reformers also believed that gardening helped young people heal physically and mentally.

Photo by Jenny Young Chandler of children convalescing while working in the farm garden at St. Giles Home in West Hempstead, Long Island, New York, 1890-1915 / THF38232

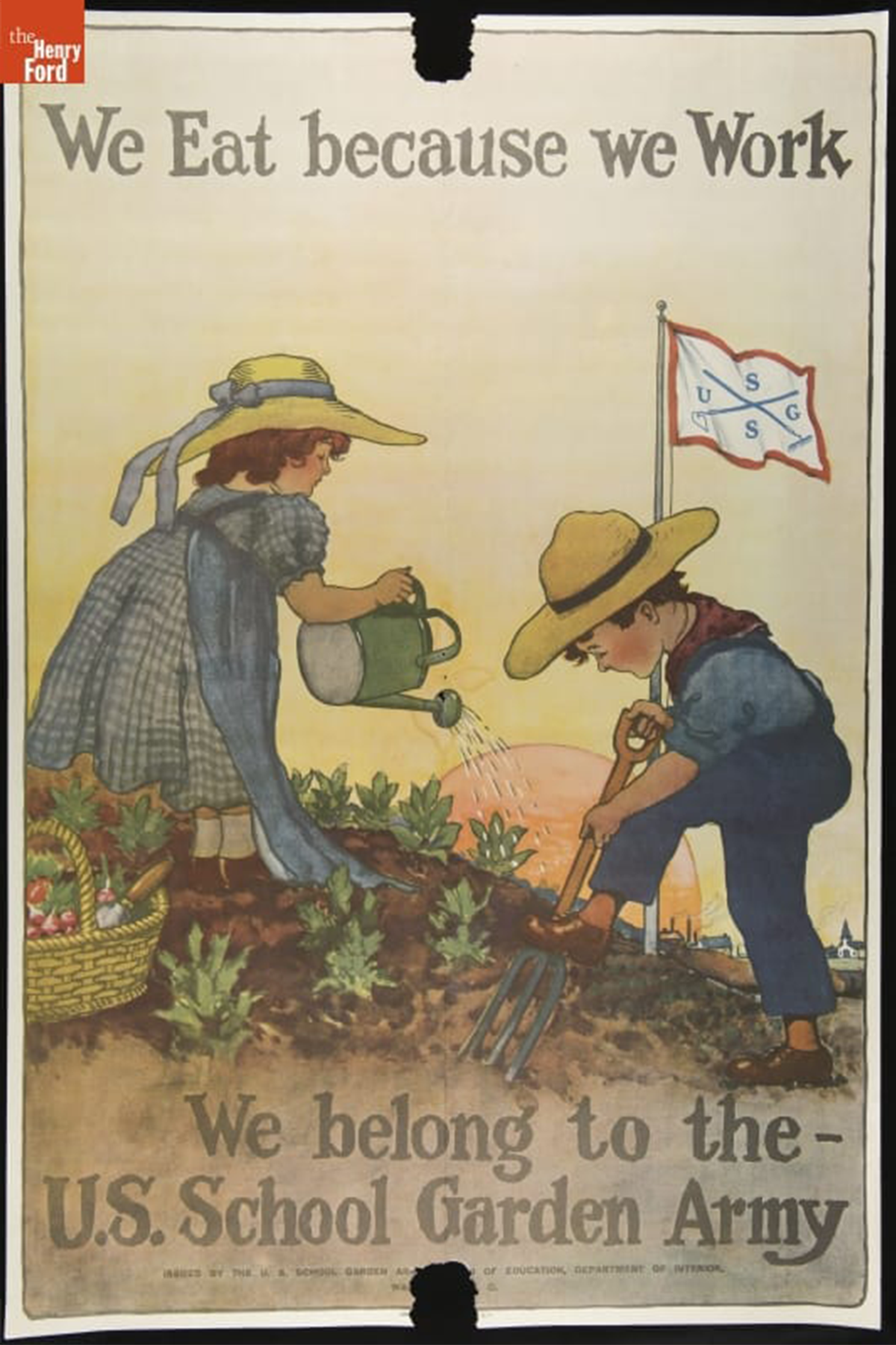

School gardens also offered opportunities for student engagement in civic affairs. The Bureau of Education within the U.S. Department of the Interior administered the U.S. School Garden Army during World War I. School gardens then became the basis for a patriotic gesture as students raised food to feed themselves, which left more food to meet the needs of U.S. troops.

We Eat Because We Work poster, U.S. School Garden Army, 1917-1918 / THF287741

School gardens had strong support among educators, urban reformers and agricultural innovators by the time the Henry Ford Trade School began in 1916. The trade school provided a safety net for boys aged 14-18 who could not continue their studies for some reason, usually because they were orphaned or the sole breadwinner in a family. Those selected received a scholarship paid out as wages and training in mechanical and academic subjects (Minute Book from Meetings of the Henry Ford Trade School Trustees, 1916-1929).

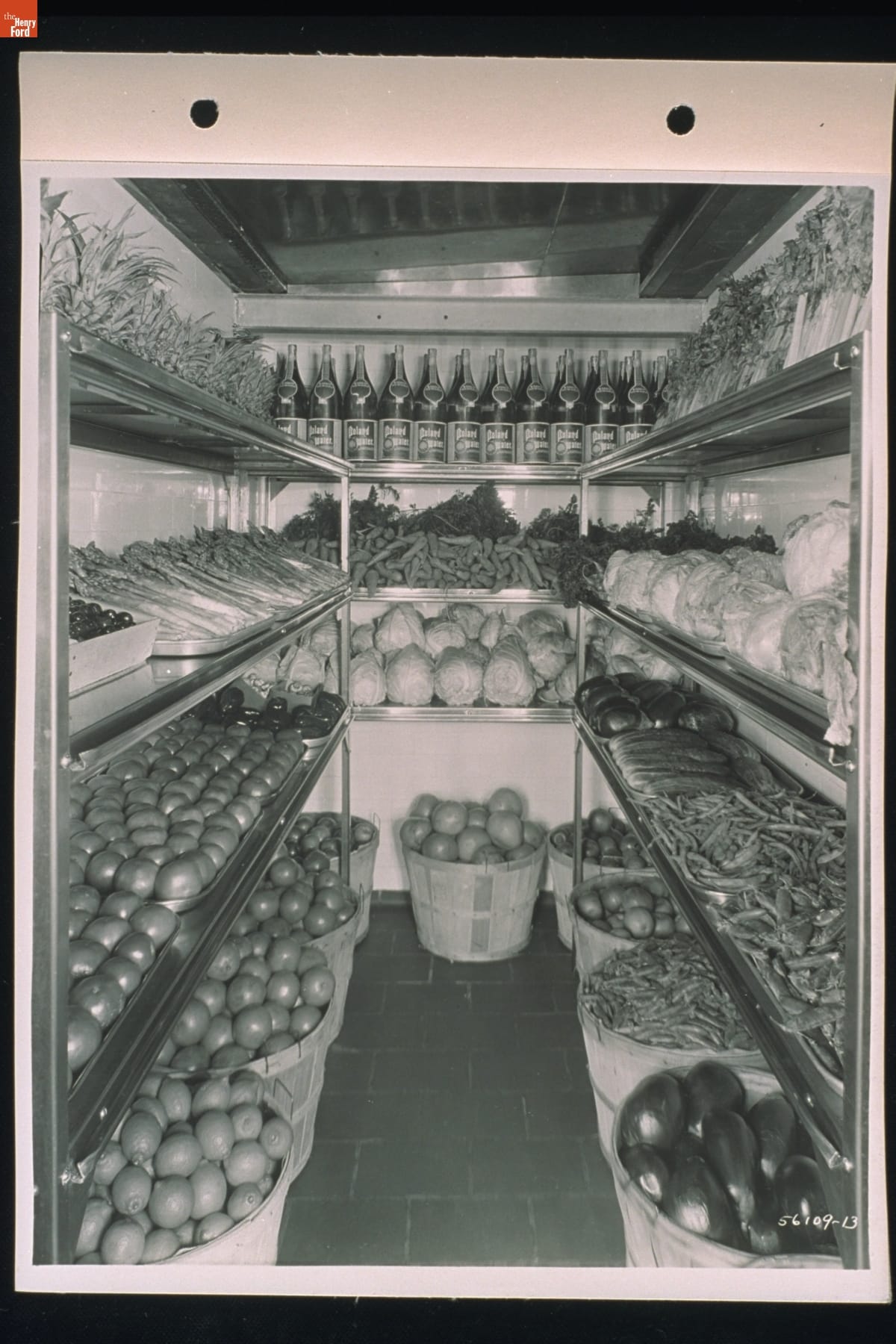

Vegetable cooler, Ford Motor Company cafeteria, May 18, 1931, likely containing produce raised at the Henry Ford Trade School / THF339056

Trade school classroom instruction included work in vegetable gardens located on acreage in Dearborn, Michigan. Students also worked on the floor at the Ford Motor Company’s Rouge Plant. The vegetables from the gardens likely made their way into the employee cafeteria at the Rouge Plant, where trade school students enrolled in technical training ate lunch. Enrollment in the trade school peaked in 1931 with 2,800 students, and a total of 8,000 young men earned their high school diplomas, complete with gardening experience, before it closed in 1952 (Henry Ford Trade School Finding Aid).

Henry Ford Trade School Students Eating Lunch, May 24, 1937 / THF626068

The Edison Institute School began in 1929. Its classroom was Greenfield Village, a part of The Edison Institute, founded by Henry Ford that same year. Students planted and cultivated vegetable gardens and harvested produce as part of their instruction. A letter to students indicated that those who gardened could take home all they wished. The rest was sold through a roadside market shed built according to Clara Ford’s plans. Proceeds totaled $4,100 in 1936, and each of the 163 students who worked in the gardens earned their share, $25.15.

Students responsible for school gardens in Greenfield Village worked through the summer months. Jack Mitchell, a member of The Edison Institute’s school garden committee, reported on their experiences during the summer and fall of 1940 in the student publication, Herald (October 11, 1940, pg. 16). In addition to what Village gardeners took home, the committee delivered wax and green beans, eggplants, beets, carrots, squash and tomatoes to the roadside market.

Edison Institute school menus included items notated “(Garden),” implying that students had the Village gardeners to thank for wax beans, string beans and eggplant on the menu for August and September 1943. Vegetables appeared daily, usually as side dishes but sometimes as the entrée, including stuffed peppers with tomatoes and sides of buttered carrots and stewed celery, and beef stew with carrots, celery, onions and new potatoes (Carl Hood, Superintendent, 1936-1945, Accession E.I.136, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford).

Students planting a garden behind McGuffey School in Greenfield Village, 1967 / THF133292

Students ate well. School administrators worked as a group to devise menus compliant with the latest nutritional guidelines. Dr. Brenton Hamil, a pediatrician who worked at Henry Ford Hospital between 1936 and 1965 and who studied child nutrition, reviewed the menus. Hamil wanted Edison Institute school staff to add the term “vegetables” to some menu items in 1942 to dispel appearances that students might be served only baked ham and escalloped potatoes or beef stew with only gravy (E.I.136).

The school vegetable garden remained a key part of instruction as students continued to plant, cultivate and harvest until The Edison Institute’s high school closed in 1952 and the elementary school in 1969.

Camp Legion boys planting fields, May 1943 / THF716943

Gardens played a key role in informal education too. Henry Ford opened Camp Legion as a summer farm project on land in Dearborn, Michigan, in 1938 for sons of dead or disabled World War I veterans. The young men earned steady wages as they worked seasonally between April and November. Camp Legion transitioned to a year-round trade school and farm project for high school boys in 1943. Then, in 1944, Camp Legion, renamed the Henry Ford School of Vocational Guidance in Agriculture and Industry, helped disabled World War II veterans secure jobs in industry or farming. The classroom included 300 acres of farmland with plenty of vegetable gardens. Faculty and administrators in the Henry Ford Trade School oversaw the program.

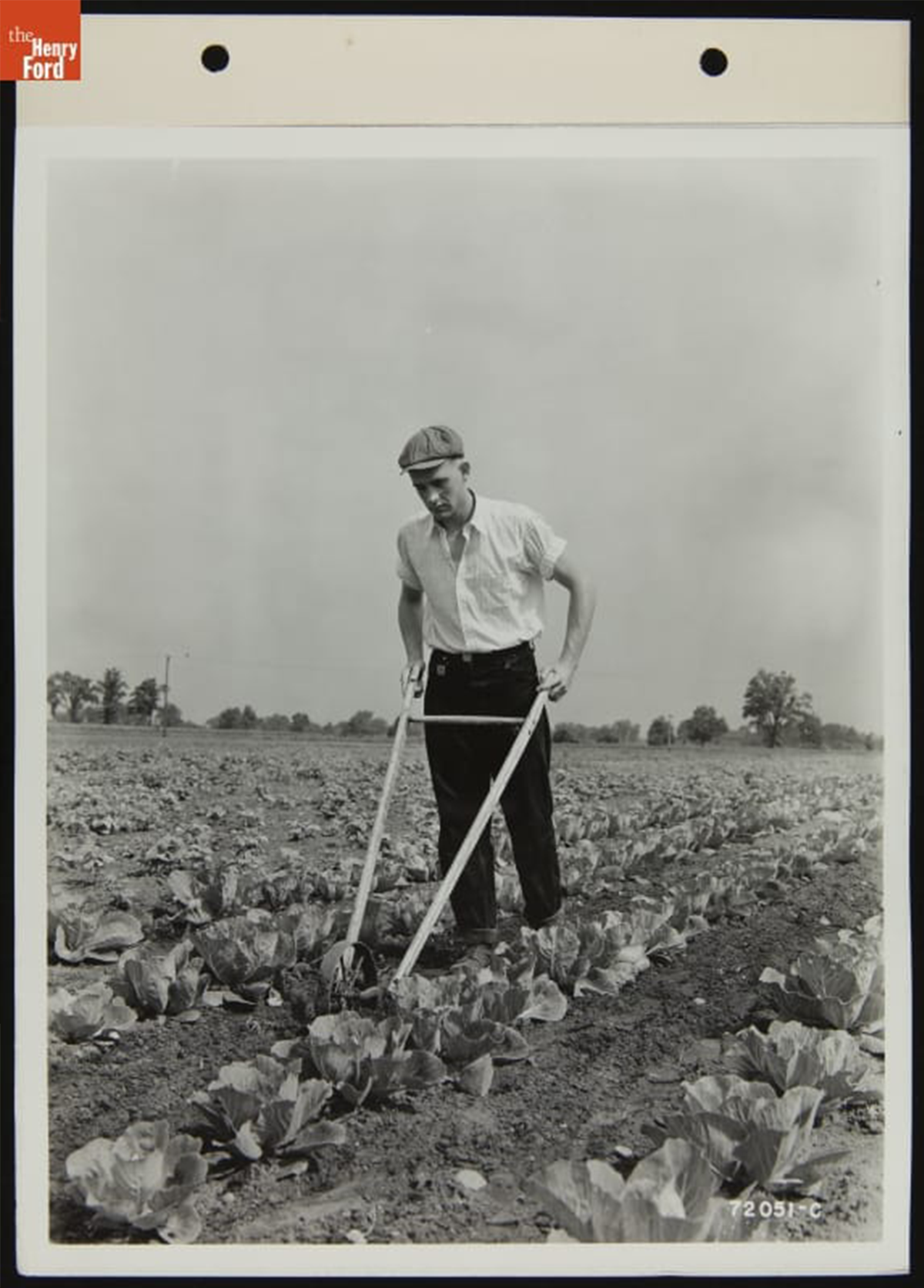

Weeding cabbages with a walking cultivator, Camp Willow Run working farm, Ypsilanti, Michigan, July 1939 / THF273610

Henry Ford opened a summer camp, Camp Willow Run, on his 975-acre farm near Ypsilanti, Michigan, in 1938. The “Back to Farm” project provided work opportunities for teenage boys who raised vegetables, worked in soybean fields and tended the farm’s apple orchard. The camp closed in early 1941 when the Ford Motor Company began construction of the Willow Run bomber plant.

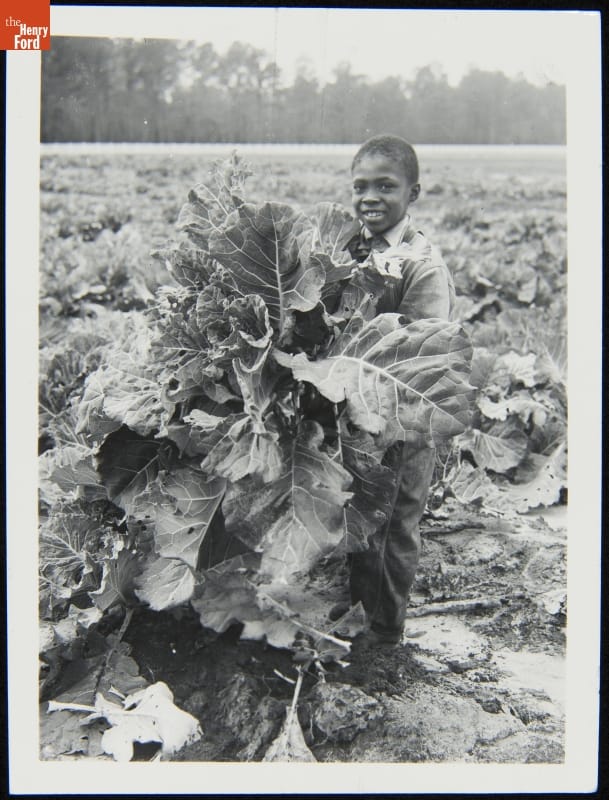

Child in a school vegetable garden holding a “big bunch” described as “a popular green vegetable in the South,” near Richmond Hill, Georgia, circa 1940 / THF288200

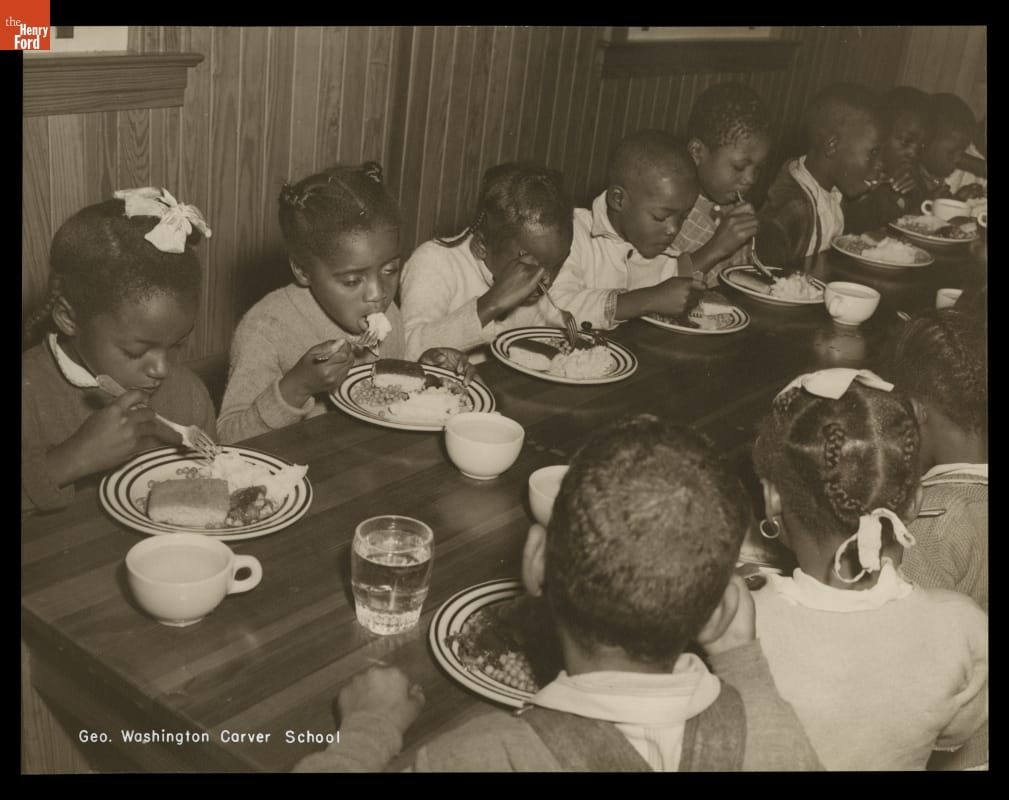

School gardens supported learning by doing for schoolchildren beyond Dearborn and the surrounding area. Students in Bryan County, Georgia, worked land near schools built by Henry Ford. This began in 1925 as Ford purchased property to build a rural industrial complex near Ways, Georgia. He built the community of Richmond Hill and, in it, schools for children of white residents. He also constructed the George Washington Carver School in 1939, located 6 miles southeast of Richmond Hill and next to the Bryan Neck Missionary Baptist Church, for children of African American residents.

Henry Ford and three youngsters with a steer harnessed to a plow, near Richmond Hill, Georgia, circa 1941 / 288103

This overview of school gardens has focused mostly on private initiatives made possible through the investment of Henry Ford. Public schools incorporated gardens into their curriculum, too, and during World War II, interest in Victory Gardens for adults and children reached an all-time high. Yet, after World War II, public and private investment in vegetable gardens decreased as many turned to processed foods to meet need. Also, national funding for school lunch programs reduced the need for students to cultivate gardens.

Elementary school children in the cafeteria at the George Washington Carver School, near Richmond Hill, Georgia, circa 1947 / THF135671

The 1946 National School Lunch Act intended to “safeguard the health and well-being of the Nation’s children and to encourage the domestic consumption of nutritious agricultural commodities and other food.” It did so by providing a subsidy to schools to ensure that children who could not afford a hot lunch could still receive one. This increased the likelihood that a student secured a hot meal, but it also eliminated the need for students to supplement their own food supply through school gardens.

Gardeners remained committed to growing their own vegetables, and gardening remained an educational activity, albeit one pursued by only a few visionaries until relatively recently. Two examples suffice. Alice Waters opened her restaurant Chez Panisse in 1971 and began a search for fresh ingredients from local sources. Her quest launched the farm-to-table movement. Most significant for youth education, she reinvigorated school gardens through a community-led effort at Martin Luther King Middle School in Berkeley, California, and startting in 1995 Waters grew it into a nationwide movement — The Edible Schoolyard. At the same time, and across the country, the public became reacquainted with gardening through the public television show Crockett’s Victory Garden (1975) and became proficient vegetable cooks with guidance from Marian Morash’s Victory Garden Cookbook (1982).

The clarity of purpose and commitment of a few with vision helped Americans reinvest in gardening — in public schools and in their own personal growing spaces.

Debra A. Reid is curator of agriculture and the environment at The Henry Ford.

For more information: The Benson Ford Research Center at The Henry Ford holds numerous archival collections with more details about each of these schools, including a Bibliography and Research Guide for Camp Legion and Camp Willow Run; Finding Aids that link to Henry Ford Trade School holdings and Finding Aids that link to records of Edison Institute Schools. Selected blogs address race, class and food security, including "Food Soldiers: Nutrition and Race Activism” and “Healthy Food to Build Healthy Communities.”