Lillian Schwartz’s Works on Paper

Lillian Schwartz (1927-2024) was a unique cultural figure as one of the American pioneers in digital art. Her work is immediately identifiable through her artistic flare. Her pieces tend to be visually jarring in a delightful way, compelling the viewer to look at them from all angles. Schwartz’s early digital art is important because it chronicles significant changes in the computer science field – from the beginnings of software to support creativity to the development of current-day tools such as Adobe Photoshop.

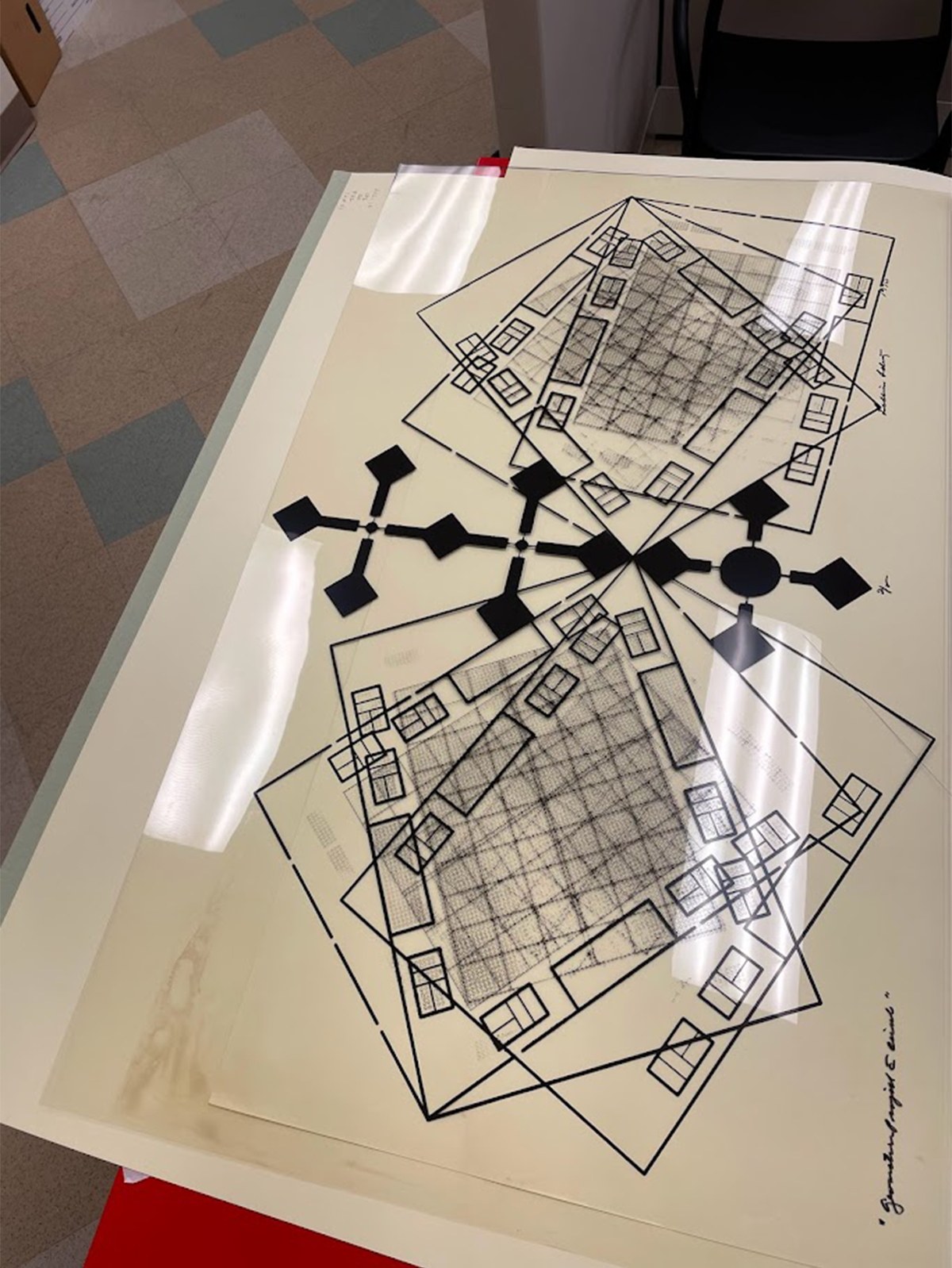

Geometrical Project with Lines, in process, 1970. Acc. 2021.14 / Photo by Regina Parsell

For Schwartz in the early 1970s, a lot of the creative process involved with her 2D works on paper took place after the pieces were printed. For example, when she designed the work Geometrical Project with Lines (1970) she broke the piece down into nine different elements and printed them individually on clear plastic (see above image). These pieces were then arranged and taped together before being copied to create the final image (see below image). Both the assembled version of the work and the copy of it were then kept, but only one displayed. In the same way that math teachers request that students show their work, so that they can follow the student’s thought process, Schwartz preserved part of her artistic genius in keeping these assembled variations, therefore allowing the researcher to better understand her process. This window into her artistic methodology is further illustrated in other works as well.

Geometrical Project with Lines, 1970. Acc. 2021.14 / Photo by Regina Parsell

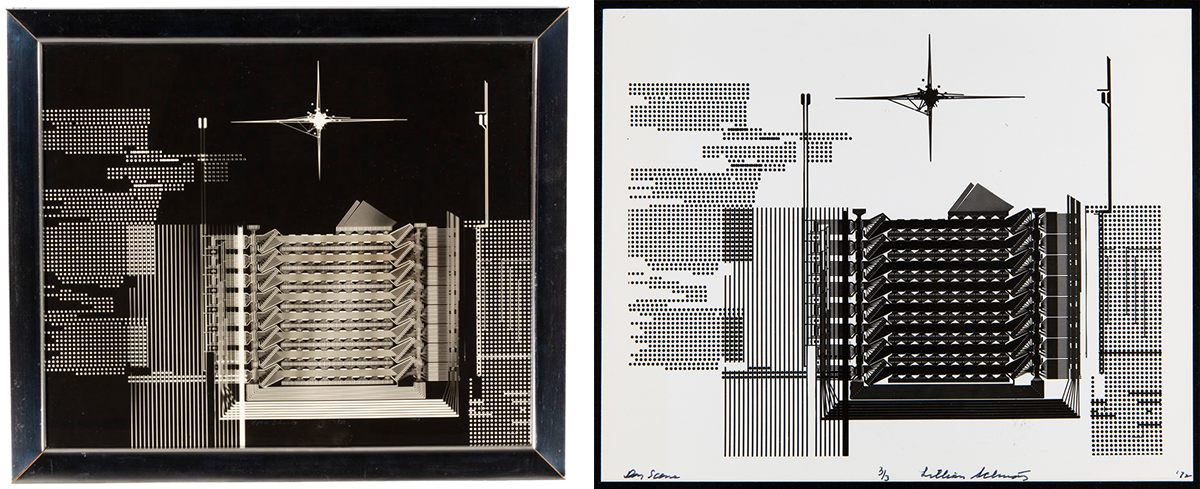

Schwartz viewed the computer as the extension of the artist and would use whatever resources she had available to create her pieces, often imagining multiple versions of a piece rather than a singular resulting image. This can be seen in the two works Variation on a Night Scene and Architecture Test, both are variants made from her works titled Day Scene and Night Scene (all created between 1970-1976). Night Scene itself is a negative of Day Scene, but by taking the central industrial style building at its center, and expanding out, Schwartz created the base image for her next two pieces (see below images).

(Left) Night Scene by Lillian Schwartz, 1986 (which were originally created in 1970-1976). Acc. 2021.14 / THF188523

(Right) Day Scene by Lillian Schwartz, 1972. Acc. 2021.14 / THF628901

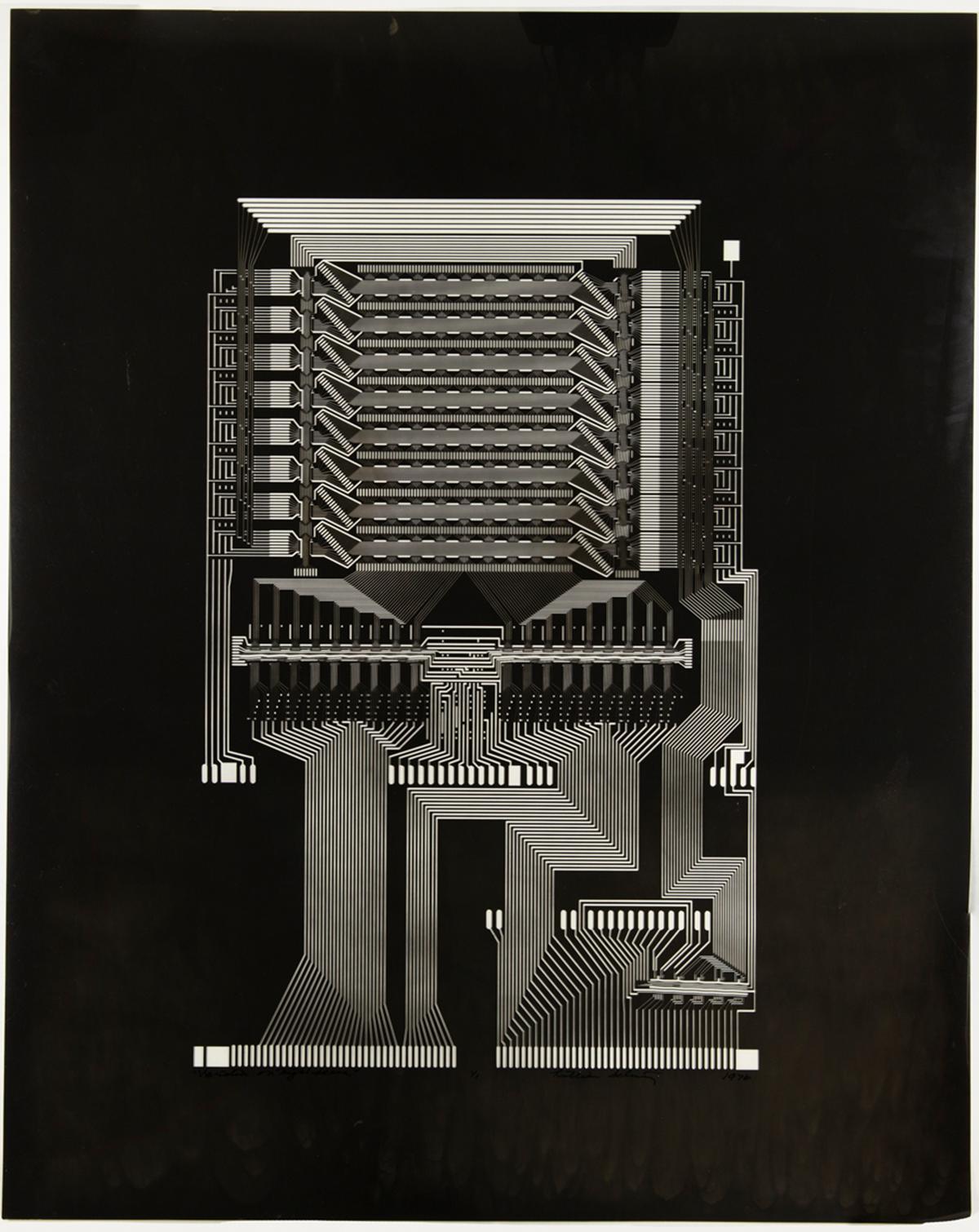

Then, taking it one step further, she used tape to black out a few of the clear horizontal lines along the bottom of the composition, and in each corner, before copying the image to make Variation on Night Scene (see below image).

Variation on Night Scene by Lillian Schwartz, 1976. Acc. 2021.14 / THF628890

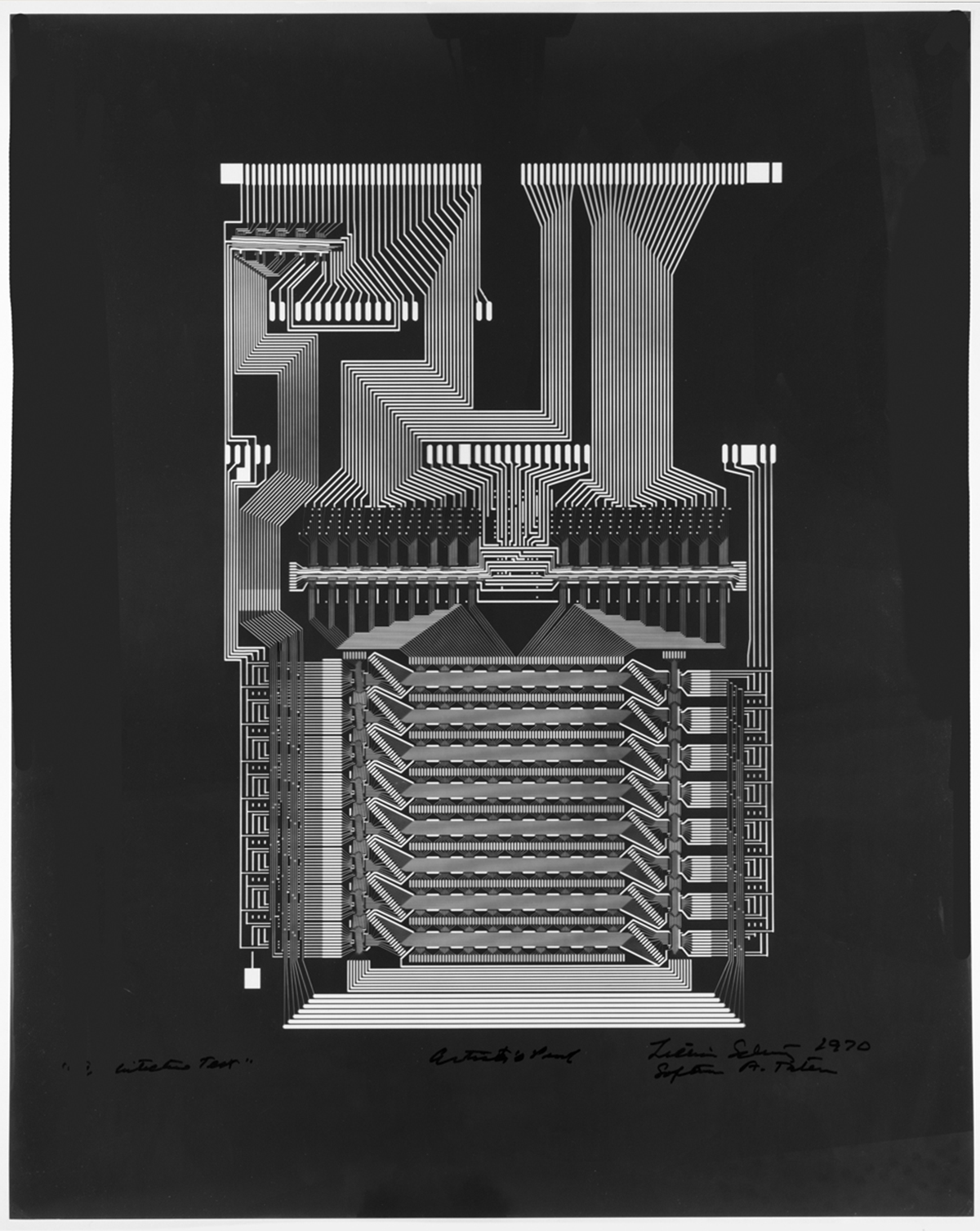

She then took that same blueprint, and flipped it upside down before copying it again, to create Architecture Test (see below image). When viewed together each composition informs the next, creating an inspired ouroboros effect.

Architecture Test by Lillian Schwartz, 1970. Acc. 2021.14 /THF719821

But it is exactly this iterative practice that can also pose a challenge for the archivist, and one of the key elements to ensuring that Schwartz’s artistic process is preserved is by arranging her archive in a way that makes sense both intellectually and artistically. While Schwartz is a unique artist,it was beneficial to explore the archives of other artists who were also exploring digital art around the same time that she was. To determine the best approach for arranging her collection, we began by reviewing established artist archives. For example, contemporaries of Schwartz include Stan VanDerBeek (1927-1984) and Vera Molnár (1924-2023), who also worked in the mediums of computer films, animation, and computer-generated and born-digital work.

Tree, Tif, by Lillian Schwartz, 2000. Acc. 2021.14 / Photo by Regina Parsell

To capture the integrity of the artists’ methodology, art collections are often arranged by project. This means that all materials related to one piece are kept together and cataloged accordingly. Before we could arrange the Schwartz collection, we had to inventory the artwork and confirm the locations of the pieces within various storage areas of The Henry Ford. The Schwartz collection is close to 400 cubic feet of materials (including research notes, ephemera, publications, project notes), of which the artwork itself is just shy of 30 cubic feet of material. Inventorying just the 2D artwork has taken about a year to complete. Now that this step is complete, the next step is to arrange the materials by using a spreadsheet to find commonalities in the pieces' descriptions and titles. A collection of this size will take several weeks to physically arrange, so there needs to be a clear plan for where the pieces are going to reside in archival storage. Once that plan has been approved, then the process of moving the materials and updating their locations in the cataloging system and inventory sheets can begin.

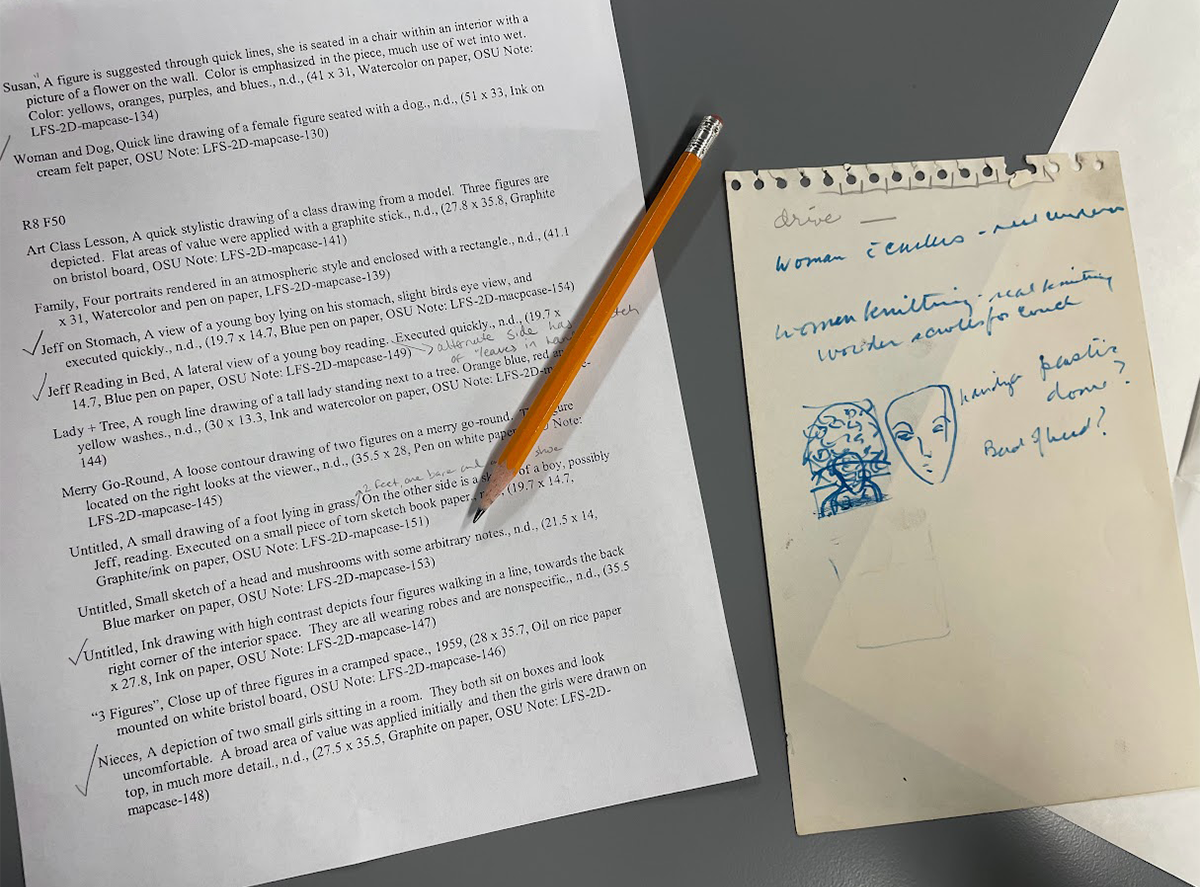

Drive by Lillian Schwartz, undated, and previous inventory of artwork located in flat files. Acc. 2021.14 / Photo by Regina Parsell

Archiving artist work and materials is important but challenging work. It asks us to think not only about how the artist intended for us to see their work, but also how the researcher will use these materials. As we expand and develop our understanding of cataloging non-traditional media, we continue to think outside the box in order to preserve their iterative process and artistic innovation. Our work with the Schwartz collection is far from complete, and while it has been complex, it has also been incredibly rewarding. One of the greatest parts of being an archivist is learning about the person from their own notes and works, and it has been a pleasure to get to know Lillian Schwartz and her work throughout this process.

Regina Parsell is a processing archivist at The Henry Ford.