Listening to Mars: Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the 1924 Mars Opposition

In August 1924—one hundred years ago—an interplanetary celestial event between Earth and Mars became an opportunity for speculation, scientific study, and inspiration. Every 26 months or so, our planet aligns in “opposition” with Mars, reducing our distance from around 140 million miles to 34.6 million miles. But not all oppositions are equal. Since Earth and Mars have elliptical orbits, every 15-17 years the distance during an opposition becomes even shorter. The view, more clear. A distance scale of millions of miles described as being “close by” is unfathomable to many of us. Still, these special “perihelion” oppositions have served as an essential time for astronomers to observe Mars and test their theories. The 1924 Mars opposition from August 22-24 was one of these special “perihelion” examples.

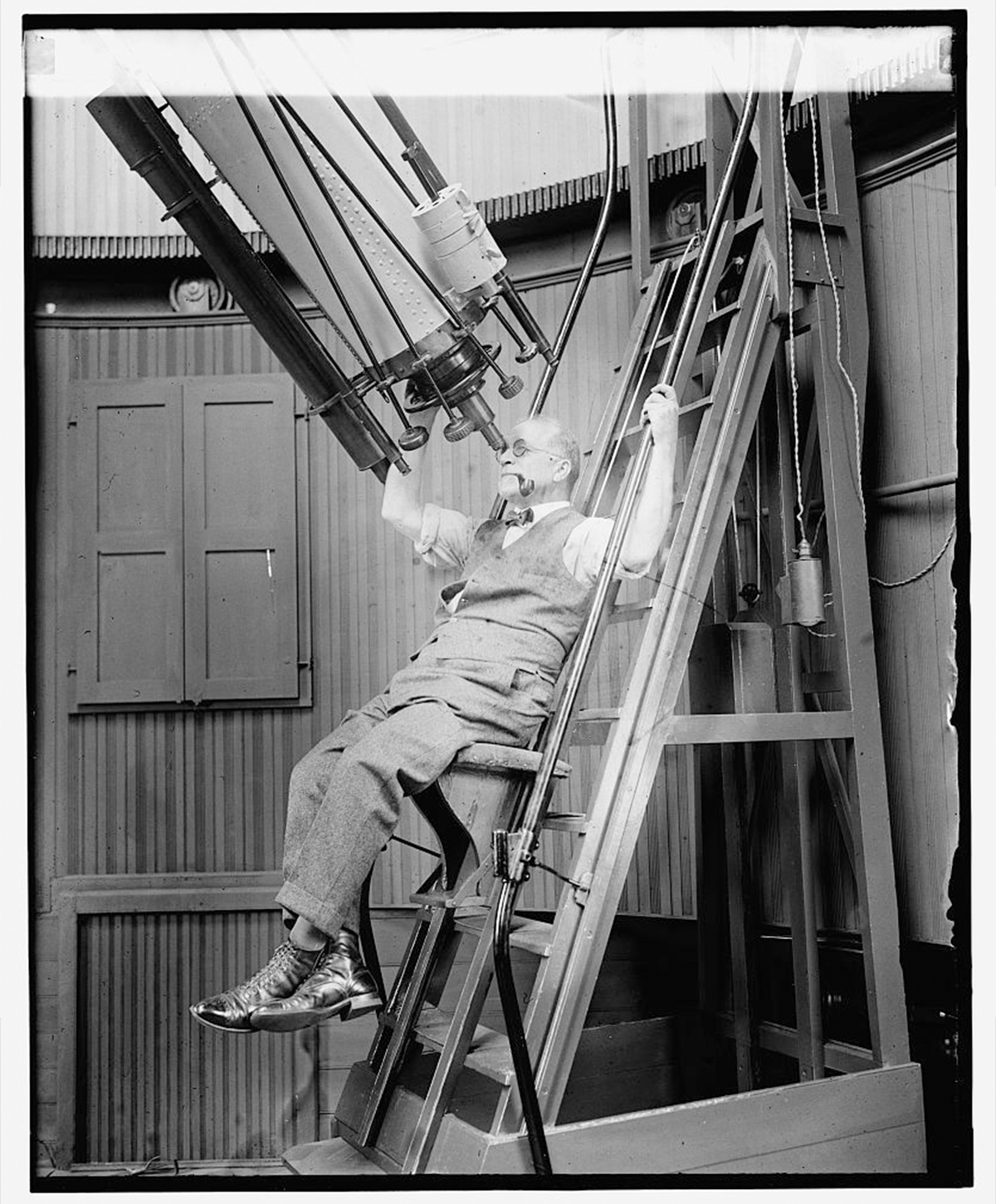

Astronomer and Mars enthusiast David Peck Todd looks through a telescope at Georgetown University Observatory, 21 August 1924 / Courtesy of National Photo Company Collection (Library of Congress)

During this time of celestial wonder, an ambitious and strange experiment occurred: an attempt to “listen” for signs of life emanating from the Red Planet. While this experiment may seem fitting in a science fiction novel, it was supported by the U.S. military and the U.S. Weather Bureau. The Army and Navy collaborated with astronomer David Peck Todd and engineer Charles Francis Jenkins as the project's leads, with the assistance of cryptographer William Friedman.

Portrait of Charles Francis Jenkins, c. 1925 / THF120578

Charles Francis Jenkins was an inventor who worked in early cinema and television technology from the 1890s into the 1930s. Many of his experimental devices used radio wave technologies to transmit and record images over long distances. While Jenkins was eager to test new reaches for his inventions across state lines, he definitely wasn’t aiming for transmission at a deep space level.

David Peck Todd was an accomplished astronomer and the former observatory director at Amherst College in Massachusetts. In 1882, he became the first person to photograph Venus's transit and later became fascinated with the “intelligent planet” theories of 19th-century astronomers Percival Lowell, Giovanni Schiaparelli, and Camille Flammarion. Todd was fascinated with the "canals of Mars" theory, which claimed that the lines crisscrossing the surface of the planet—observed by Todd and others through telescopes—were Martian-made irrigation canals. In reality, these lines proved to be an optical illusion caused by telescope lenses of the time, but the hope remained for Todd. Seeking to achieve extraterrestrial communication, Todd convinced the military to cooperate with his plan to harness the 1924 opposition as an ideal time to gather “signals from Mars.”

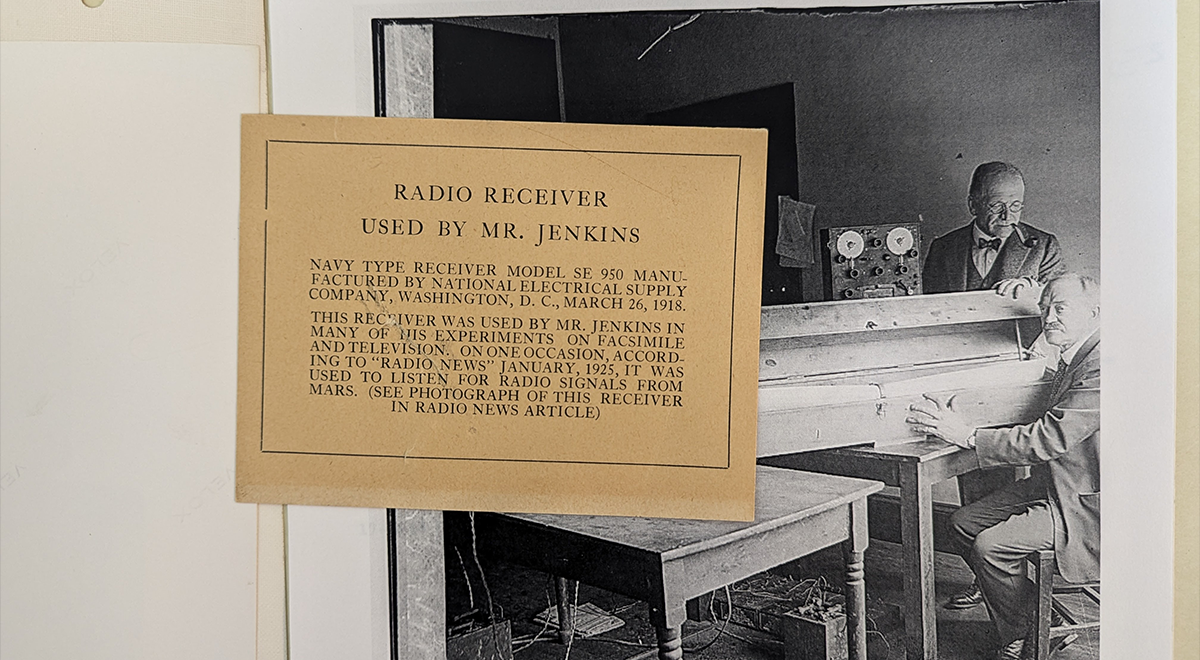

Label from a former exhibit at The Henry Ford with details about Jenkins’ SE-950 radio. The radio is visible in the image above, to the left of Todd (standing). Jenkins is seated with another component of the Jenkins Radio Camera / Image by Kristen Gallerneaux

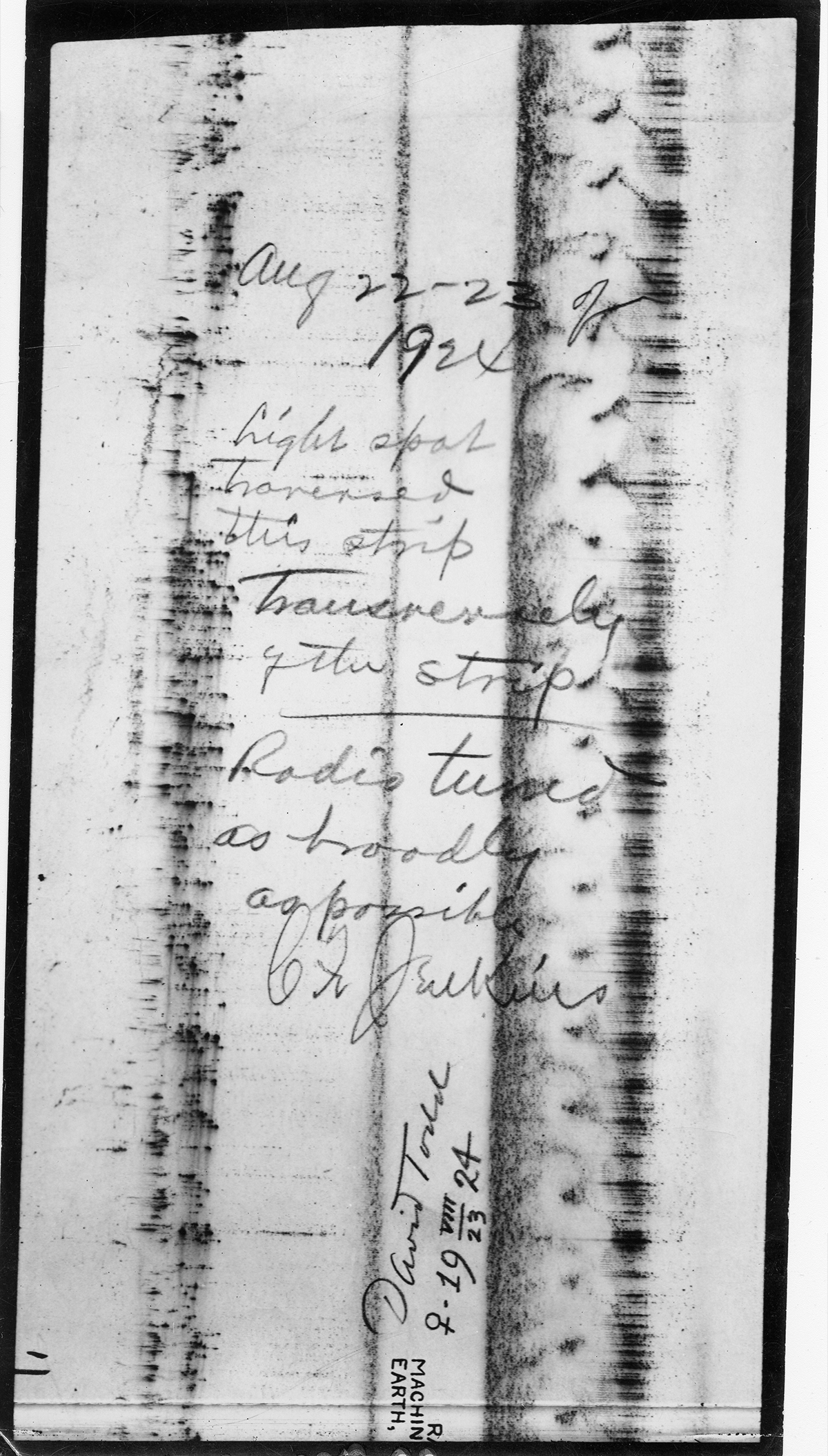

The short version of this story is that during the peak of the Mars opposition, on August 22-24, the military would request periods of radio silence each day—any rogue signals that bled through Jenkins’ and Todd’s equipment could, in theory, prove the existence of life on Mars. On the ground, the devices used to “listen” for signals were Jenkins’ “radio photo message continuous transmission machine” (more simply, the Jenkins Radio Camera) and a SE-950 NESCO radio. If any signals were detected, they would be translated into flashes of light, exposing static-like forms onto a 30-foot long piece of photographic paper fed onto spools in the wooden box seen in the image above.

Radio Receiver, Type SE-950, used by Charles Francis Jenkins in experiment detecting radio signals from Mars / THF156814

For his part, Jenkins was skeptical and tried to distance himself from Todd’s belief to protect his reputation as a scientist. Throughout the experiment, static did filter through the Jenkins Radio Camera. William Friedman, the cryptographer, could not make sense of it. The public interpreted these signals visually, believing they were seeing the form of a human face in the static. The fervor quickly died down when it became obvious that the interference was likely caused by radio heterodyning, from passing trolley cars, or even the natural radio waves of Jupiter.

Radio signals collected during the 1924 Mars opposition by Todd and Jenkins using the “radio photo message continuous transmission machine” / Courtesy of Yale University Archives, David Peck Todd papers

The Henry Ford’s collections contain many of Jenkins’ prototypes and experimental technologies that he used in his laboratories, which came to us in 1940 through Jenkins’ widow, Grace Love Jenkins. What remains of Jenkins' apparatus used during the 1924 Mars opposition? In this curious stretch of three days, technology was pushed beyond what it was ever intended to do. This SE-950 radio is a poetic conduit in communication history—and believed to be the last remaining three-dimensional object used in the experiment. The rest of the Jenkins Radio Camera is believed to be lost, although the photographs of the messages received during August 1924 are located in the Yale University Archives.

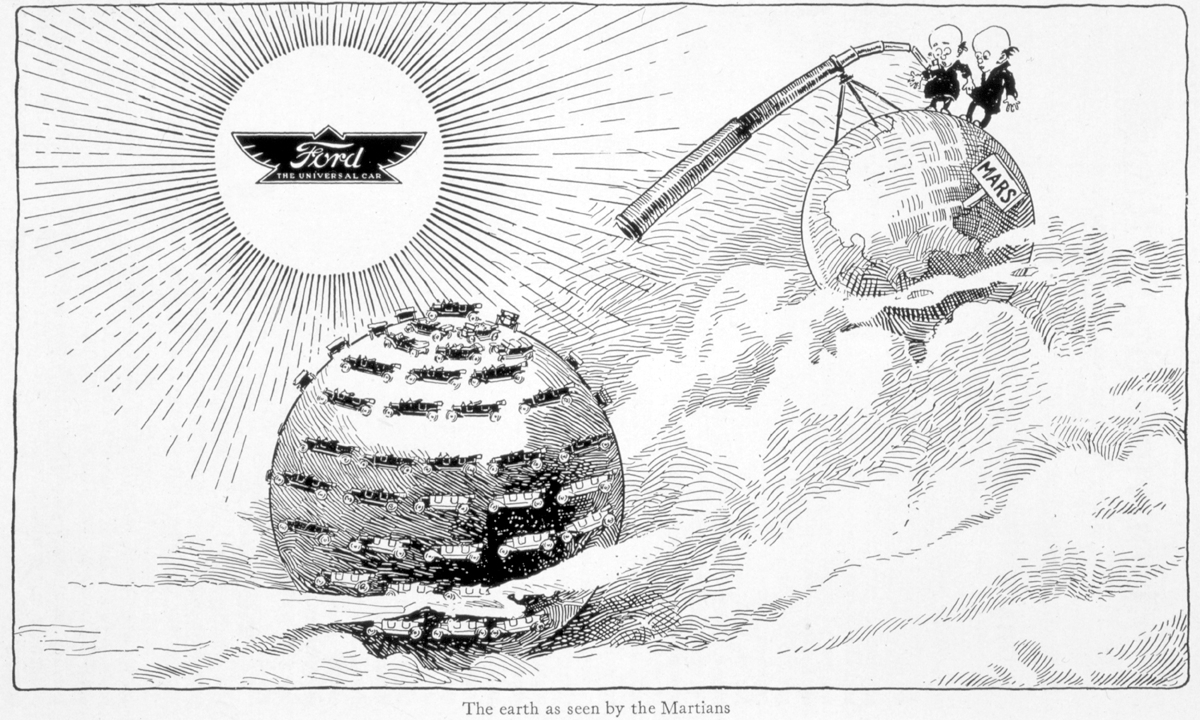

Illustration from the December 1913 issue of Ford Times, predating the 1924 Mars opposition. What if the tables were turned, with Mars observing Earth? / THF3205

This experiment is often cited as part of the lineage that led to the formation of organizations like the SETI Institute, which employs scientific experts to search for intelligent life in the universe. A century later, the events of August 1924—reported on, rediscovered, and recently rediscovered once again as we near the 100th anniversary—continue to find new audiences. Celestial events like solar eclipses, comets, and meteor showers inspire people to seek out collective moments of awe-inspiring wonder, sometimes travelling long distances for the best view of these fleeting moments. Readers who can relate might broaden their celestial horizons to consider the history of public and scientific fascination with Mars, which will be in opposition to Earth in January 2025, February 2027, and March 2029. For the next extra special “perihelion” opposition, akin to the one that happened in 1924 though? You’ll need to wait a little longer, until 2035.

Kristen Gallerneaux is curator of communications & information technology and the editor-in-chief of digital curation.

Facebook Comments