Mazda Advertising Posters and the Lighting Milestones That Inspired Them

With Earth’s revolution around the sun, the changing of the seasons often brings with it a greater awareness of the role that light plays in our lives — from the sun setting earlier to shadows thrown differently across surfaces. Our adaptations that assist with navigating life in the dimming sunlight mean we are reliant on lighting devices to illuminate our lives — a relationship that has extended into the deep, dark corners of human history.

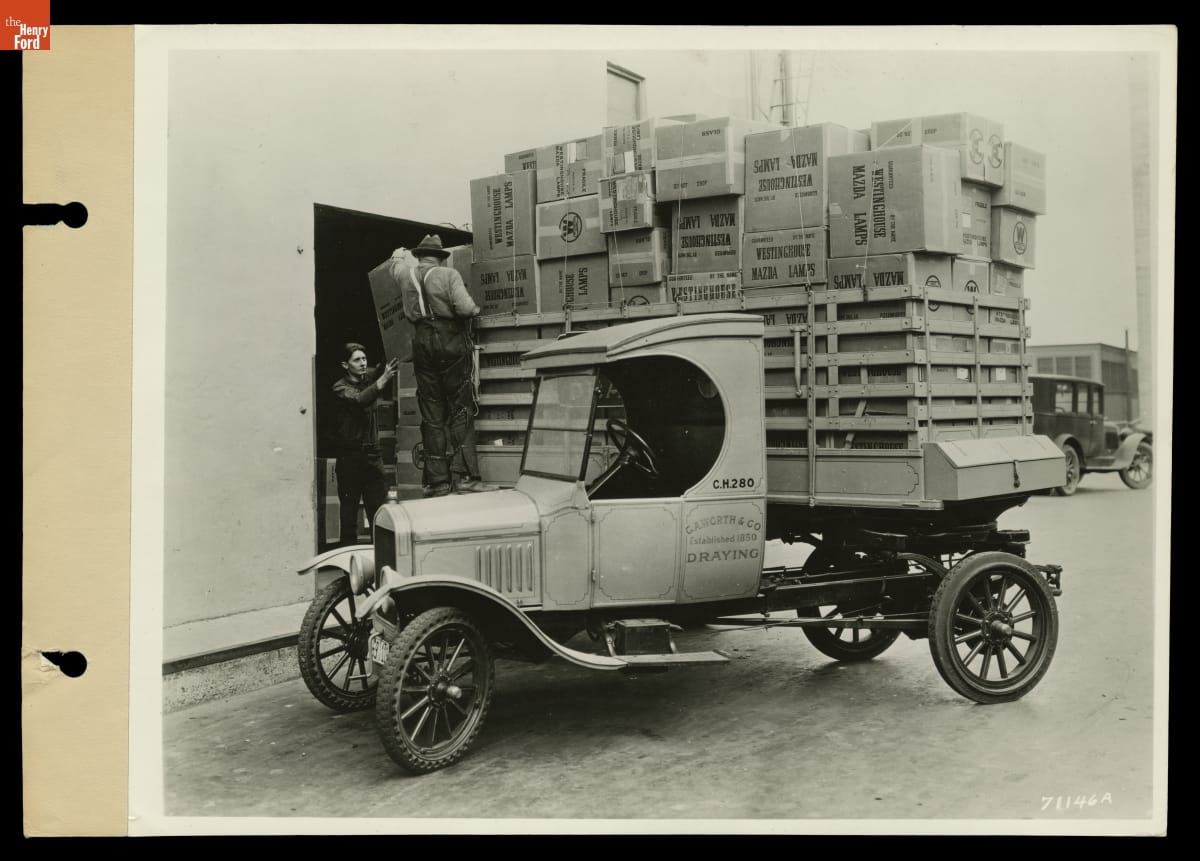

Loading boxes of Westinghouse Mazda Lamps onto a Ford truck, 1925. Many lighting companies, including Westinghouse, licensed the “Mazda” name from General Electric for their own tungsten filament bulbs. / THF122784

Beginning in the early 1920s, General Electric explored the human relationship with lighting devices when it commissioned illustrators Maxfield Parrish and Norman Rockwell to create a group of advertising illustrations for its popular light bulb known by its trademark as the Mazda lamp. Their artwork not only drew upon “the goodness of life in the light,” but also traced the history of lighting devices. The following is an exploration of those advertising posters, supplemented with a few examples from The Henry Ford’s collection of the lighting devices they celebrate.

Left: One of Norman Rockwell's earliest and most successful advertising campaigns was for General Electric. Right: During the mid-1920s, most Christmas lamps had the Mazda name on them, as General Electric and Westinghouse were the largest suppliers of light bulbs in the United States. / THF8203, THF191123

At the turn of the 20th century, General Electric saw an urgent need to create brighter bulbs with more reliable filaments to tap into a large U.S. market. To do so, the company invested heavily in metallurgical research, hiring engineer William David Coolidge in 1905 from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to isolate a metal with properties that could increase the reliability — and commercial viability — of their light bulbs using carbon filaments previously invented by Thomas Edison. By 1909, after years of work, Coolidge had developed a process to turn the known metal, tungsten, from a brittle, unworkable material into a durable, ductile filament that glowed white-hot and rendered lifelike colors. General Electric marketed their tungsten filaments under the brand name Mazda, a reference to Ahura Mazda, the ancient Persian god of Zoroastrianism associated with wisdom – and light. By 1916, the sale of bulbs using tungsten filaments had eclipsed the sale of carbon filament ones, making up nearly all incandescent bulb sales in the United States. Use of tungsten filaments lasted nearly a century, only displaced within the past several decades by more efficient compact fluorescent and LED technology.

Left: Rockwell’s illustrations appeared as magazine advertisements, posters and point-of-purchase signs. Right: Paper Horseshoe Filament Lamp Used at New Year's Eve Demonstration of the Edison Lighting System, 1879. / THF6535, THF174078

Before the tungsten filament bulb, General Electric’s main consumer product was carbon filament bulbs that combined Thomas Edison’s filament discoveries with bulb technology from English inventor Joseph Swan. In 1879, Edison had “brought light to the world” with a horseshoe-shaped carbon filament during a New Year’s Eve demonstration at his Menlo Park research laboratory after months of trial-and-error experimenting with filament material. His work on light bulbs or “lamps” was only one component of a larger electrical system he envisioned, a system he eventually achieved in 1882 with his Pearl Street generating station in New York City. Prior to developing a practical incandescent lamp, Edison’s plan to replace gaslight systems in lower Manhattan with a complete electric lighting system won him the backing of financiers like J.P. Morgan and the Vanderbilt family who wanted patentable products. Together, they formed the Edison Electric Light Company, which merged with other companies in1892 to form General Electric.

Left: By 1927, Norman Rockwell had created at least 20 advertising illustrations, like this poster, for use in General Electric’s magazine ads and store displays. Right: Kerosene Lamp, 1860-1870, currently on display at the Ford Home in Greenfield Village. / THF8201, THF307027

Around the time of Edison’s experiments with incandescent lamps, the market for lighting was dominated by lamps running on “rock oil.” In the 1840s, Canadian Abraham Gesner began experimenting with hydrocarbons and the liquids he derived from them, specifically one he called “kerosene.” With kerosene, Gesner had developed a fuel that burned cleaner than other lamp oils of the period derived from animals, and one that could be produced cheaper from abundant natural hydrocarbon resources like coal and petroleum. Gesner moved to New York in the 1850s where he started the North American Kerosene Gas Light Company and built one of the first refineries to mass-produce kerosene. With other forms of lighting reserved for the wealthy and candles providing dim, easily extinguished light, kerosene became a reliable lighting product accessible to the middle class. Later, even as the nation became increasingly electrified, kerosene lamps remained in use.

Left: During the 1910s and 1920s, Maxfield Parrish worked with popular magazines and created advertising art, as seen here, for companies like Colgate, Oneida Cutlery, and General Electric. Right: Whale Oil Lamp, 1830-1856. / THF8199, THF155550

Prior to kerosene, oil lamps were fueled by the whaling industry along North America’s eastern coast, where the eventual industrialization of harvesting brought whale populations to near extinction. Beginning in New England during the 1690s, and throughout the early 19th century, whale oil, and whaling in general, supported many profitable industries. Varying species of whale provided different kinds of oil that offered lighting possibilities to primarily the wealthy and allowed for the smokeless illumination of businesses (as well as provided lubrication for machines of the early Industrial Revolution). The double wick, common on whale oil lamps, makes use of the lamp’s heat to warm both the wick and the oil reservoir to keep the oil thin, allowing it to climb the wick more easily and burn more brightly. By the time the whaling industry peaked in the 1850s, millions of gallons of whale oil had been harvested, but fuel options were growing.

Advertising Poster for Edison Mazda Lamps, "The Right Light Increases the Joy of Living," circa 1922. Illustration by Maxfield Parrish. / THF6533

The technology of the Mazda lamp, while innovative, relied on the illustrations featured in these advertising posters to convince people of its beneficial use. General Electric spared no expense when it came to the promotion of its product, and talented artists abounded as increasingly popular magazines of the early 1920s fueled a flourishing era for printed advertisements. It’s no surprise, then, that General Electric engaged with top talent of the time, tapping the well-established painter and illustrator Maxfield Parrish, who had illustrated many successful advertising campaigns, books and magazine covers, along with the up-and-coming Norman Rockwell, a young artist already impressing with his work for The Saturday Evening Post. In a sense, these posters not only verified the Mazda lamp’s soon-to-be rightful spot in the history of lighting but also the legacies of the artists that helped shine a light on it.

Ryan Jelso is an associate curator at The Henry Ford.