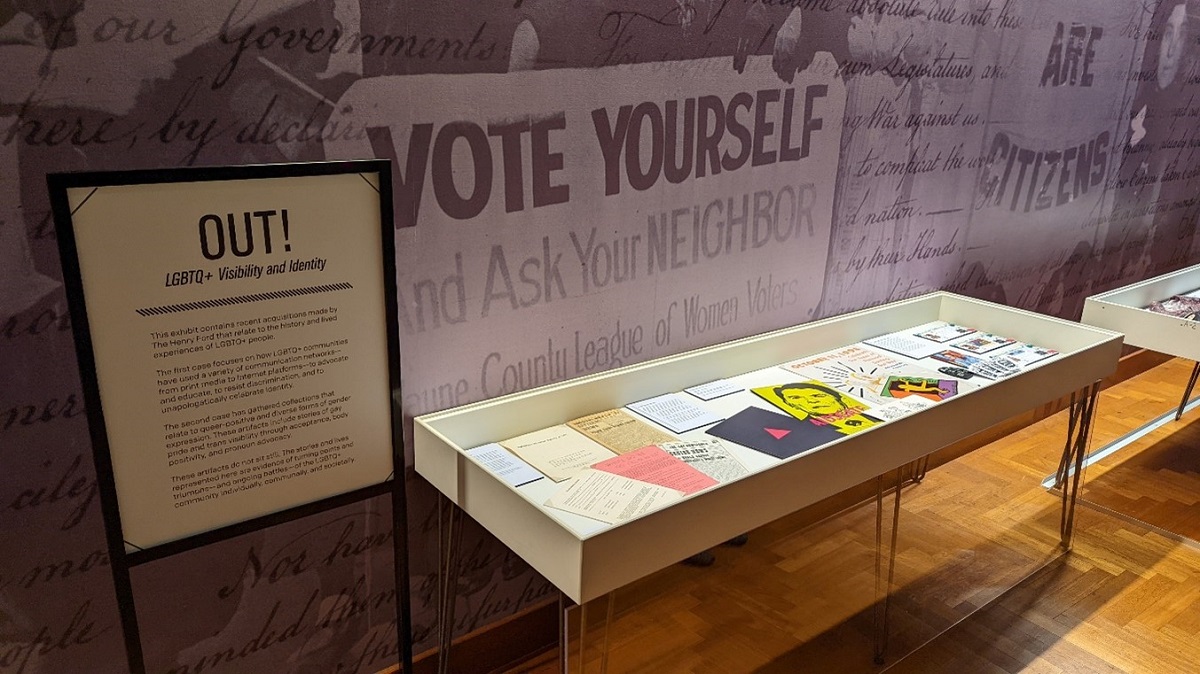

OUT!: LGBTQ+ Visibility and Identity

Photo by Kristen Gallerneaux/Katherine White

In 2022, The Henry Ford displayed a temporary exhibit, OUT!: LGBTQ+ Visibility and Identity, at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. The exhibit, co-curated by Kristen Gallerneaux and Katherine White and featuring items from The Henry Ford's collections, contained recent acquisitions that relate to the history and lived experiences of LGBTQ+ people.

The first theme explored in this exhibit was how LGBTQ+ communities have used a variety of communication networks—from print media to Internet platforms—to advocate and educate, to resist discrimination, and to unapologetically celebrate identity.

The second major theme gathered collections that relate to queer-positive and diverse forms of gender expression. These artifacts included stories of gay pride and trans visibility through acceptance, body positivity, and pronoun advocacy.

These artifacts do not sit still. The stories and lives represented in OUT!: LGBTQ+ Visibility and Identity are evidence of turning points and triumphs—and ongoing battles—of the LGBTQ+ community individually, communally, and societally.

Getting the Word Out

In the 1960s, LGBTQ+ people faced a largely unaccepting American society and legal landscape that restricted how they could express themselves. Queer bars and clubs were among the only private, “safe” spaces, for LGBTQ+ patrons but they were also easy targets for police, who harassed and arrested patrons. On June 28, 1969, New York City police raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay club in Greenwich Village. A riot ensued.

Queer bars and clubs also became sites of community and connection—even amidst persecution and harassment—and became fertile soil for the burgeoning queer liberation movement. LGBTQ+ newspapers were distributed in these spaces, broadcasting news unlikely to be shared in mainstream media. Print media like these unified queer/LGBTQ+ people in the fight for acceptance and equality through sharing manifestos, organizing protests, and recruiting members.

Today, we recognize the legacy of the Stonewall Riots as the genesis for the Pride marches that celebrate the LGBTQ+ community every June, in cities big and small across America. .jpg?sfvrsn=e6cd3601_2)

THF627212.jpg?sfvrsn=b2cd3601_2)

THF627336

These fliers were created by New York City’s chapter of The Mattachine Society, one of the oldest gay rights groups in America, in the months following the Stonewall Riot. They illustrate the urgency felt by the queer community in the wake of persistent and brutal police violence.

Raising Awareness

In the early and mid-1980s, activist collectives formed to raise awareness of HIV and AIDS. This advocacy was critical, since government and public health organizations initially refused to act or acknowledge the developing crisis. Misinformation about HIV and AIDS transmission was widespread, and so LGBTQ leaders and allies spoke up—demanding an end to negligence, access to testing, treatment options, and vetted public education about HIV prevention..jpg?sfvrsn=aacd3601_2)

THF179775.jpg?sfvrsn=9acd3601_2)

THF627370

The Silence=Death Collective’s “AIDSgate” poster condemns then-president Ronald Reagan’s lack of response to the AIDS epidemic. In 1981, the first AIDS cases in the United States; President Reagan did not recognize AIDS in a public speech until September 1985..jpg?sfvrsn=eecd3601_2)

THF627366.jpg?sfvrsn=86cd3601_2)

THF627364

Howard Cruse, author of the acclaimed graphic novel Stuck Rubber Baby, uses the slogan of the Gay Liberation Front in the top drawing above: “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it!” The “Gay is Good” illustration mimics historical photographs of protestors at the 1969 Stonewall Uprising that were also referenced in the “Gay Liberation” poster by Su Negrin, Peter Hujar, and Suzanne Bevier.

THF190487

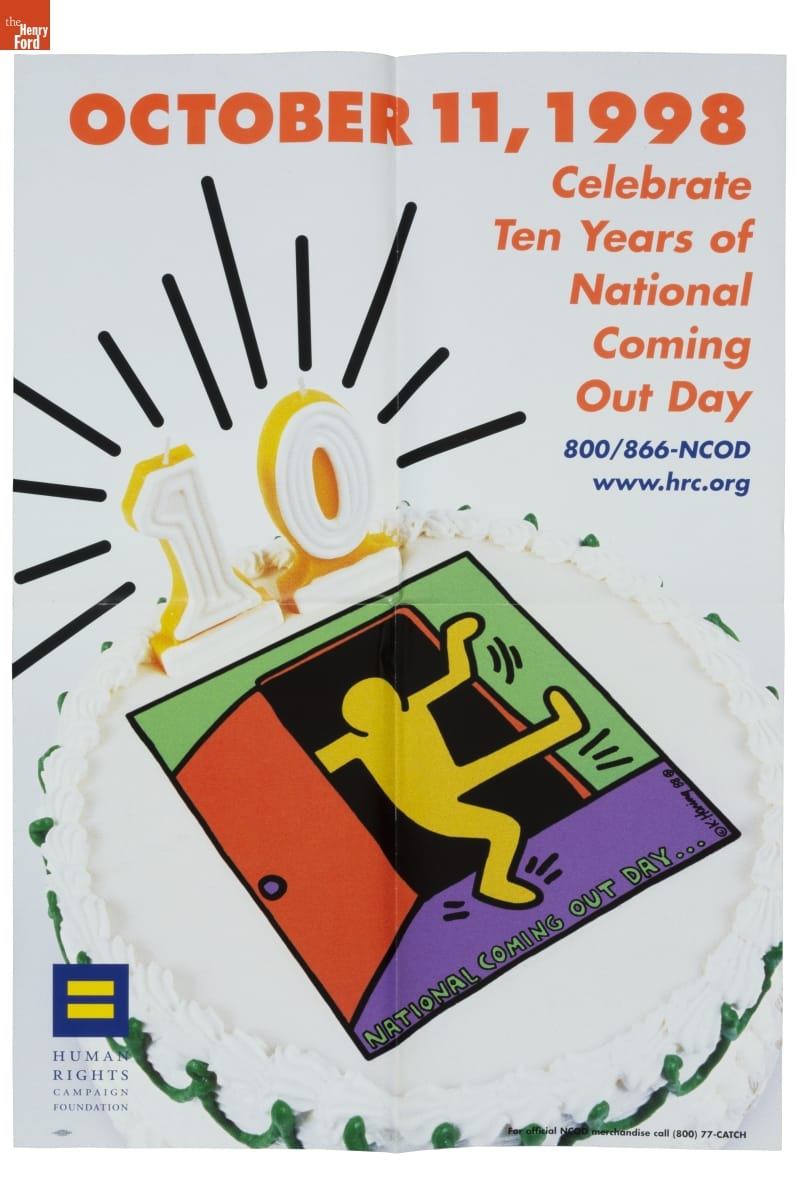

In 1988, Richard Eichberg and Jean O’Leary founded Coming Out Day to provide resources for LGBTQ+ people wishing to publicly declare their identity. The pair believed that “coming out” would promote solidarity and acceptance while reducing homophobia. The Human Rights Campaign (an LGBTQ+ advocacy and political lobbying group) sponsors this event in the United States. This poster commemorates the 10th anniversary of the observance, which remains active in 2022. The logo of a person dancing their way out of a closet depicted on the cake on this poster references artist Keith Haring’s original NCOD logo.

Online Identity & Safe Spaces

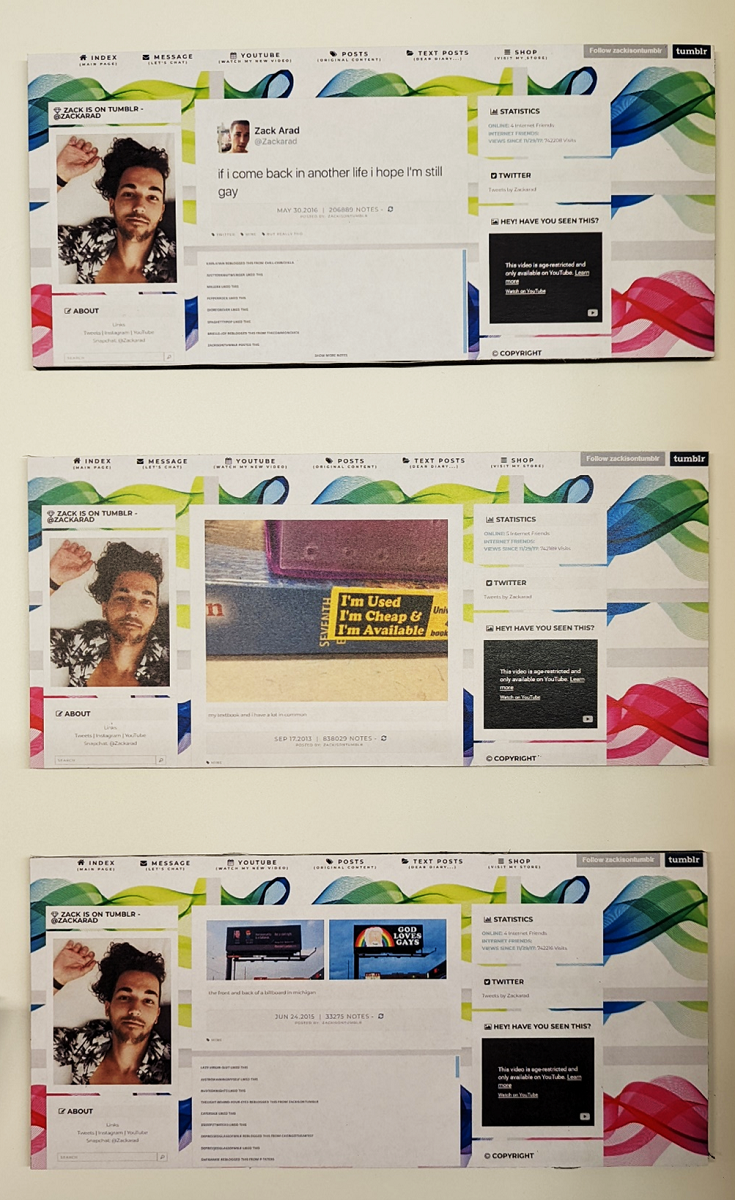

Online platforms can act as digital “safe spaces” for LGBTQ+ community-building. Beginning with Usenet bulletin board systems in the 1980s and transitioning to LiveJournal, Twitter, and Tumblr in the 2000s, these sites can act as support networks for LGBTQ+ people—including those who live in isolated areas or in situations where openly exploring identity poses challenges AFK (away from keyboard).

Photo by Kristen Gallerneaux/Katherine White

Zack Arad launched a microblog on July 21, 2010. Arad, who self-identifies as gay, has been active on social media since he was a teenager. His popular Tumblr blog and YouTube vlogs explore themes like gay pride, pop culture, humor, dating, and political issues.

Photo by Kristen Gallerneaux/Katherine White

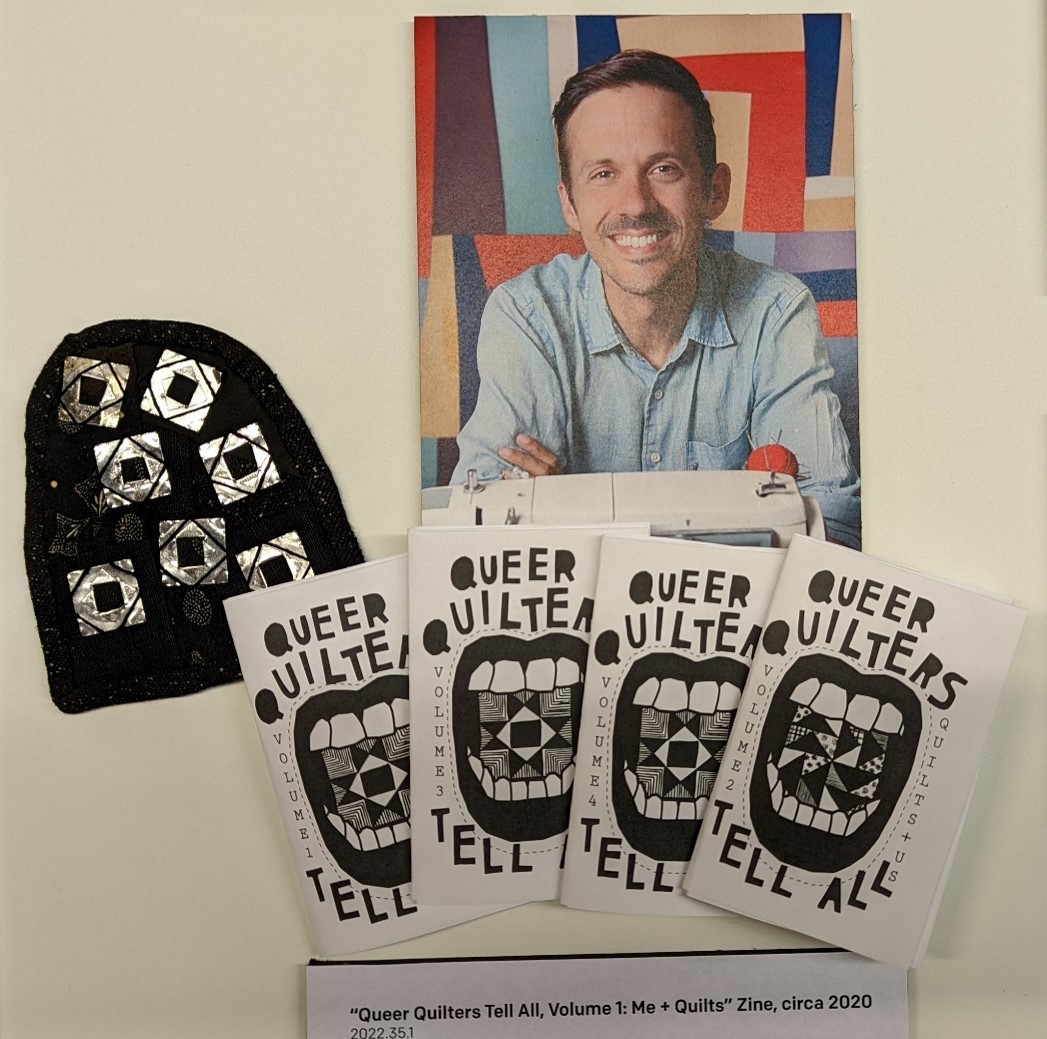

This “mini-quilt” was created by Zak Foster, a textile artist who identifies as gay and has a strong online following for their work, selling one-of-a-kind upcycled quilts on Etsy. With Grace Rother, Foster also created this collection of “zines,” and distributed them online “as a love offering … to all the queer folks in the quilting community.”

Identity & Solidarity

Buttons, patches, badges, and pins are consciousness-raising, inexpensive, quick to create, and able to be distributed widely. Wearing a button can be a method of activism. When simply being “out” as LGBTQ+ means possible danger and discrimination, choosing to wear a visible symbol of queerness is a courageous act. .jpg?sfvrsn=becd3601_2)

THF189705

The cap above was worn by a member of a California-based gay motorcycle club. Among the oldest gay organizations in the United States, these clubs emphasized hypermasculinity, which appealed to many gay men who had long been stereotyped as effeminate.

Photo by Kristen Gallerneaux/Katherine White

Many of the buttons featured here use symbols or terms that were once weaponized against the LGBTQ+ community but were later reclaimed. The inverted pink triangle, for example, has its roots in the Holocaust, when Nazis forced queer people to wear a pink triangle as a form of identification and persecution. By repurposing these symbols, a shared and recognizable language of identity and solidarity is created among LGBTQ+ people and allies.

Trans Acceptance

Transgender and nonbinary people have always existed, across time and in every corner of the world—just as have gay, bisexual, lesbian, and other queer communities. But acceptance by the broader world has been difficult to achieve. Even the early leaders of the LGBTQ+ equality movement pushed the transgender community to the fringes. For many transgender and nonbinary individuals, the realization that their gender identity does not align with their assigned-at-birth gender comes long before even their own acceptance and celebration of it.

THF190453

THF611162

Miley Kirby came out publicly and applied trans flag patches to her medic bag during Detroit’s Black Lives Matter protests, which held supplies used to provide medical care to fellow protestors. Kirby is visible carrying this same bag in the center of the press photo above, published in the Detroit News during the Black Lives Matter protests of Summer 2020.

“The people I met at the [George Floyd] protest were one of the first groups of people that encouraged me to be me. They refused to let me cop out on pronouns, names, or hand-waving of my transness for others comfort. We yelled our message in the streets, why not scream your identity to the world? My time in those protests found me my voice as Miley Kirby, or at least the beginning of one.” – Miley Kirby

THF190458

Allie Zecivic listened to an insistent inner voice and purchased this dress, her first article of women’s clothing. It helped her to accept her gender identity as a transwoman.

“Hot Topic skinny jeans and too tight graphic tees were alright, but this was a dress. A long, flowy, spinny dress. I spent a lot of time sitting alone in my room wearing it, my heart racing and the paranoia spinning horrible outcomes in my head, but it felt right. The validation that dress brought was freeing. It was this feeling in the face of trepidation of being caught, that solidified my need for more. And such my wardrobe grew.” – Allie Zecivic

THF190456

THF190457

Laura Bowman began the medical transition to female with these hormone replacement therapy medications. She crossed out her “deadname”—the male name she was given at birth—and kept these bottles as symbols of her journey.

“Hormones don't make a transperson trans, but for many of us they are the beginning of the end. The end of the old life, and the beginning of a new experience, a new chance to be who we want to be, to make the outside fit how we feel inside. When I first picked up these pill bottles, I felt a giant weight off my chest as it felt like I was going to be able to make some progress on that person in the mirror and come to like her just a little better. The major part of that comes when you change the way you perceive yourself, but damn do the hormones help!” –Laura Bowman

Body Positive

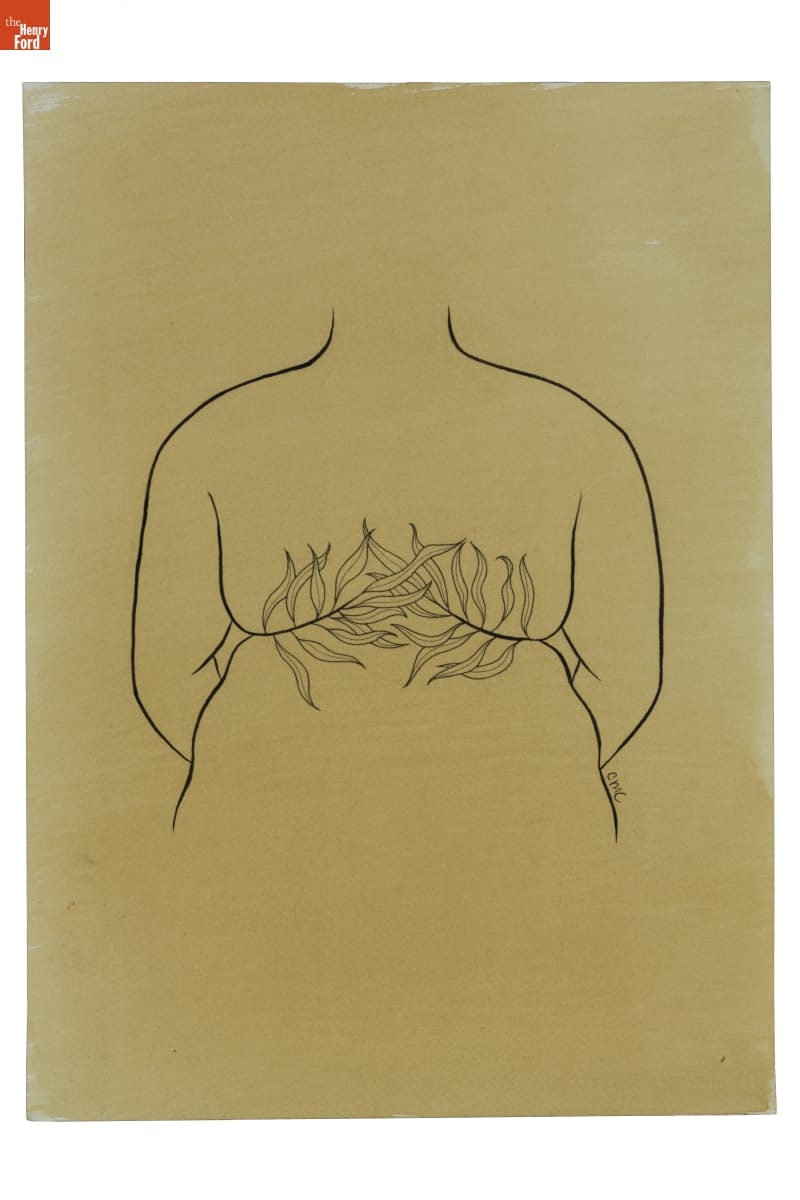

Carrie Metz-Caporusso is an artist and tattooer who identifies as queer and non-binary. They began tattooing in 2011 and are committed to challenging traditions in tattooing culture that sometimes stigmatize LGBTQ+ and larger-bodied people. After experiencing fat shaming in the tattooing world, Carrie brainstormed a way to celebrate—rather than conceal—plus-sized body types with custom “roll flower” tattoos. These tattoos align with the body positivity movement by embracing the natural folds and creases on client’s backs or sides, which serve as a “stem” for flowers and leaves emerging from above and below.

THF190488

THF190489

These signature “roll flower” tattoo flash designs were drawn and donated by Metz-Caporusso to The Henry Ford. In 2022, The Henry Ford commissioned Metz-Caporusso to create illustrations for apparel, which will soon be available in museum stores.

Photo courtesy of Carrie Metz-Caporusso

Mother of the Movement

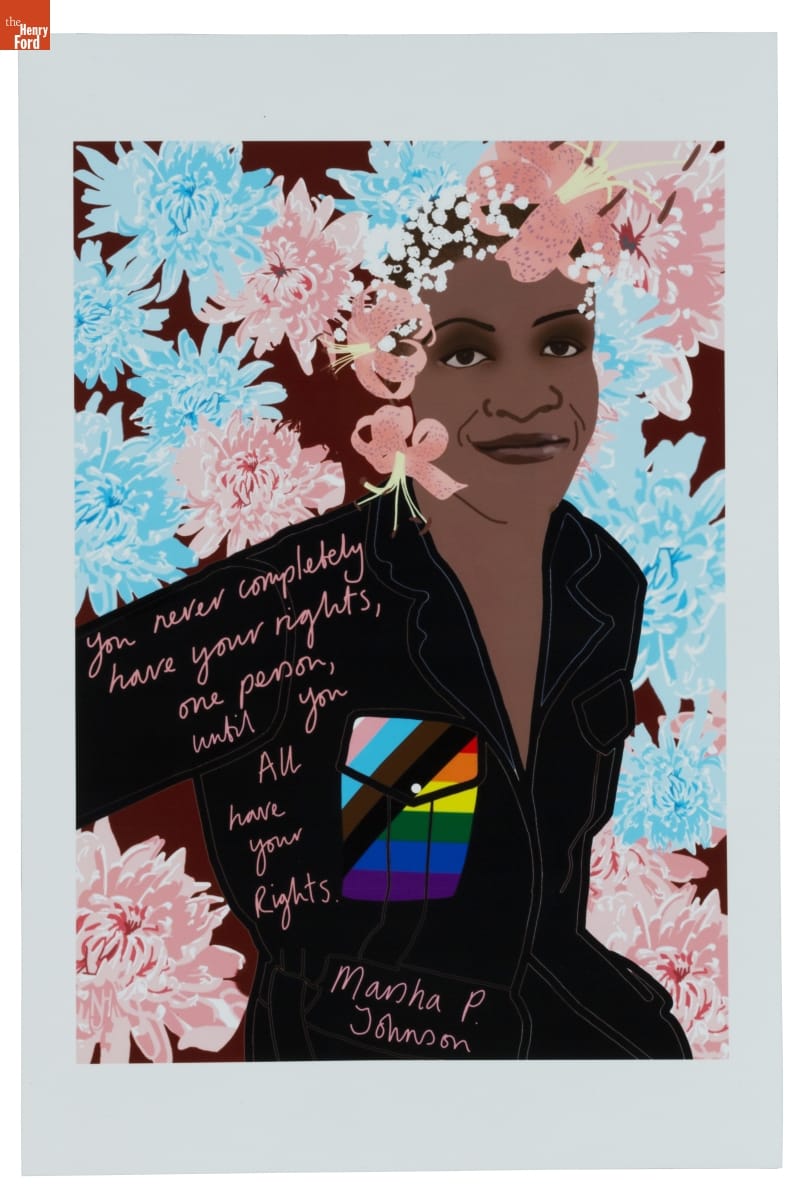

Marsha “Pay It No Mind” Johnson was a New York City–based drag performer and activist who identified as a gay transvestite (the term transgender was not used at that time).

She was tireless in her advocacy for gay rights. From the mid-1960s on, she was an active presence—often a mischievous instigator—at almost every major uprising, parade, and political action connected to the LGBTQ+ equality movement. She clashed with police during the Stonewall Uprising, helped create the Gay Liberation Front, and participated in AIDS awareness group ACT-UP. With Sylvia Rivera, Johnson was a “house mother” for the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries—a political collective and homeless shelter for trans youth of color. Johnson died under suspicious circumstances in 1992—believed by many to be a victim of anti-gay violence.

THF190491

This print, created by Julia Feliz in 2018, honors the intersectional legacies of Black LGBTQ+ leaders, as well as Daniel Quasar’s redesign of the Pride Flag to include stripes for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) and trans people.

Listening to the Community

The stories and lives represented in this exhibit just barely scratch the surface of what it means to be LGBTQ+ in the United States. Visibility often increases vulnerability—and backlash. Bigotry, discrimination, and social justice issues related to equal rights and access continue to impact LGBTQ+ people around the world.

Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communications & Information Technology at The Henry Ford, and Katherine White, Associate Curator at The Henry Ford, collaboratively produced this exhibit and blog.

Henry Ford Museum, by Katherine White, by Kristen Gallerneaux