A Piano with a Past

Talented African American jazz pianists played this piano at Detroit’s Club Harlem during the mid-1930s. How did the piano acquire its ivory finish? A few years after Club Harlem closed, the Warblers moved to Allen Park. The piano went with them. Perhaps the ivory lacquer was added by Maurine Warbler—a more appropriate look, perhaps, for a piano that now resided in a suburban home THF166445 (From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Allene Warbler in Remembrance of Her Parents Allen and Rene Warbler.)

The quiet ivory exterior of this unassuming little piano belies its jazz-infused past. Hidden beneath the ivory lacquer are glimpses of silver that offer a clue to its former life. Not only did this piano have a “front row seat” at one of the many jazz clubs that dotted Detroit’s Paradise Valley district during the 1930s and 1940s—it was part of the show.

In March 1934, this piano left the Wurlitzer company’s DeKalb, Illinois factory for its new destination—Detroit. It was delivered to a jazz club called Club Harlem, housed in the basement of the Lawn Apartment building on Vernor at Brush. To give the piano an appropriately “jazzy” look, the club’s managers painted over the piano’s rather reserved mahogany factory finish with aluminum paint. The back of the piano—the side visible to the audience—was covered with black velvet, decorated with large glittery musical notes. The piano’s small size—only 61-keys instead of the standard 88—was likely an asset to upstart Club Harlem in what may have been tight quarters filled with patrons in this basement nightclub. Too, its small size made it more affordable than a standard upright piano. Detroit’s economy was only beginning its slow and uneven recovery from the depths of the Depression.

More Alcohol, More Jazz

The timing of this new club’s opening in early 1934 was no accident. Prohibition had ended the previous December—it was again legal to manufacture, sell and transport intoxicating beverages in the United States. During the 13 years that prohibition had been in force, “underground” establishments had continued to discreetly serve patrons liquor, as well as often offering food and live shows. Now they could do it openly.

During the 1920s, jazz, a musical form rooted in the African American experience, had taken America—and the world—by storm. The fresh, lively sound of jazz was different than anything that had come before. It was the perfect “accompaniment”—in fact, helped define—this more modern era. A 1919 song, Take Me to the Land of Jazz, captured things perfectly with these lyrics, “How in every cabaret, it’s the only thing they play.”

Detroit's Paradise Valley

During the 1930s, a commercial center emerged in an area of Detroit (bounded by Gratiot, Vernor, Brush and Hastings streets) that became known as Paradise Valley. Racial discrimination had sequestered the city’s African American population into a tight-knit and vibrant community on Detroit’s near east side. Here, black-owned businesses dotted the streets and Detroit’s African American community could shop, eat, and enjoy their leisure time. Paradise Valley--with its clubs, theaters and dance halls—would become the major entertainment spot in Detroit, as a growing number of nightspots offered places where jazz could be enjoyed. Talented African American musicians and singers, including Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, and Louis Armstrong, lit up the nights. Paradise Valley experienced its most rapid growth after Prohibition ended in 1933, with many jazz clubs--including Club Harlem--added during the following decade.

During the day, Paradise Valley was predominantly Black. At night and into the wee hours of the morning, Paradise Valley became more racially balanced, as many white Detroiters sought the entertainment opportunities found there. A major factor was the development of the black-and-tan nightclub, which catered to both African American and white audiences. Club Harlem, located at the northern boundary of Paradise Valley, was one of these black-and-tan jazz clubs. Many of the black-and-tan clubs in the district were owned by African American businessmen. A few, like Club Harlem, were owned by whites.

Club Harlem

Club Harlem’s owner was Morris Wasserman. Wasserman ran a loan business and owned a pawn shop. (It was said that Wasserman also had ties to Detroit’s notorious Purple Gang, criminals involved in the illegal liquor trade during Prohibition.) Wasserman hired Allen Warbler to manage the club. Warbler had previously worked for Jean Goldkette, a prominent band organizer and booking agent, at Goldkette’s popular Detroit ballroom, the Graystone, during its heyday of the 1920s. Warbler's wife, Maurine, who had worked for a theatrical booking agent, designed many of the costumes worn by the chorus performers at Club Harlem.

Among the performers who played Club Harlem was 19-year-old Milt Buckner. Orphaned at the age of 9 and adopted by members of Earl Walton’s band, Milt and his brother Ted were prominent jazz musicians in 1930s Detroit. A few years later, Milt Buckner would join Lionel Hampton’s band as pianist and key music arranger. Bands headed by Monk Culp and Ernest Cooper also played Club Harlem. Other musicians who entertained Club Harlem’s audiences were 23-year-old saxophone player Charles “Tubby” Bowen, who would later lead a band under the name Tubby Bowen and His Tubs, and 25-year-old Sammy Price, a Texas pianist who became the house pianist for Decca Records in New York City in 1938, recording with many of New York’s jazz and blues greats.

Club Harlem had a short run--it operated from just 1934 to 1935. Club Harlem’s piano, once played by musicians like Milt Buckner and Sammy Price, ended its jazz career. Allen Warbler, Club Harlem’s manager, went into the real restate business. Club Harlem’s owner, Morris Wasserman, would open the Flame Show Bar on John R in Detroit in 1949. The Flame Show Bar would become one of the city’s major jazz clubs during the 1950s.

Pianist Sammy Price in a publicity shot from the mid-1930s THF249299. (From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Allene Warbler in Remembrance of Her Parents Allen and Rene Warbler.)

These young women were likely dancers in Club Harlem’s “Shim Sham Shimmy” chorus THF249293 (From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Allene Warbler in Remembrance of Her Parents Allen and Rene Warbler.)

Farewell to Paradise Valley

From the 1930s into the early 1950s, Paradise Valley bustled. But, in the 1950s and 1960s, urban renewal projects designed to “modernize” the city while eradicating “blight,” along with freeway construction for I-75, erased this vibrant African American community—scattering its inhabitants. Little remained of Paradise Valley and neighboring Black Bottom (named by French explorers for its rich soil), where the majority of Detroit’s African American community resided in rundown clapboard houses built to house the flood of German immigrants who arrived in the 1850s. No efforts were made by the city to support the relocation of the African Americans who had resided there. Detroit’s urban renewal projects—and their devastating effect on this community—helped fuel the growing resentment against racial discrimination that would culminate in the 1967 Detroit civil unrest.

A little of Paradise Valley hung on for a few decades, though. The 606 Horse Shoe Lounge was the last remaining nightclub from the glory days of Detroit’s Paradise Valley. The club was located at 606 E. Adams from the 1930s to the 1950s. It had featured a floor show, an orchestra, and its owner John R. “Buffalo” James as emcee. Construction of the I-75 freeway forced the club to relocate to 1907 N. St. Antoine by the early 1960s. This last vestige of Paradise Valley’s legendary jazz clubs was demolished in 2002, the building razed as part of the Ford Field construction.

The 606 Horse Shoe Lounge was the last remaining nightclub from Detroit’s legendary Paradise Valley THF166450 (From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Arthur A. Jadach.)

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 1930s, popular culture, musical instruments, music, Michigan, Detroit, by Jeanine Head Miller, African American history

Math, Music, and the Matrix

This scene could almost be a slick DJ club set, but there are no knobs, decks or instruments in sight. Yet the code is real, and it’s all live.

This is the world of live-coding music, an art form in which performers create music by programming computers on the fly, in front of an audience, writing and revising instructions that trigger and manipulate sounds, rhythms and effects in real time.

THE MATH OF MUSIC

When it comes to expressing musical ideas, computer programming might seem an unlikely outlet. But computer science is grounded in math, and music, with all of its messy, imprecise human expression, is largely built on mathematical relationships — harmonic structure, rhythmic patterns, and at its most fundamental, the unique combinations of sine waves that make up the sounds all around you, from birdsong to the roar of a jet engine.

We’ve been exploring parallels between music and math since the days of Pythagoras. Today, musicians and composers are able to use computers as tools to interpret and express these values and relationships.

“It’s clearer through coding that music can be expressed as essentially patterns of numbers that are processed and transformed in various ways — and that we can add expressivity by changing the sounds we are using and shaping the structure of our sounds,” said Shelly Knotts, a composer, experimental artist and live coder in the United Kingdom.

As a live coder learns to anticipate these mathematical relationships, his or her ears learn to “hear” the relationships, much like in traditional music theory training. Live coders often write code that they can hear in their heads — which, at a fundamental level, relates to Beethoven’s ability to continue composing even after he had completely lost his hearing.

BREAKING DOWN BARRIERS

Live-coding languages and styles vary. Most performers create music entirely on the fly, constructing ideas from scratch; a few mix in precoded elements, DJ-style. But they all embrace the movement’s overarching philosophy that live coding should be inclusive and accessible to everyone.

For most live coders, exposing their code is part of the performance and serves to demystify their process, forging a connection with the artist through his or her “instrument,” explained Sam Aaron, a British researcher, software architect, educator and live coder. “Why is it important for a guitarist to let you see his or her guitar? People have all held guitars; most of us are not very good at it, so when you see someone who’s good at it, you can appreciate the virtuosity.”

There’s no denying that projecting computer code adds a compelling visual element to a performance, but if you’re not paying attention to the language itself, you’re missing the point. “It’s like saying Jimi Hendrix made amazing music, but he had a fabulous wooden necklace,” added Aaron.

Live coding challenges preconceived ideas about the programmer’s experience by bringing a traditionally solitary process into a participatory realm. “It’s like writing, really; you don’t generally write in a social way,” said British musician and researcher Alex McLean, member of the live-coding band Slub and cofounder of TOPLAP, an organization formed in 2004 to bring live-coding communities together. “I think live coding is not necessarily showing programmers as something different, but rather a different way of interacting with the computer; it’s very different, working alone on a piece of text and having people in front of you, listening intently,” added McLean, who is also credited with co-inventing the algorave, a rave-like club event based around live coding.

Since its inception about 15 years ago, live-coding culture has been rooted largely in Europe and the U.K., but the movement is slowly building international interest through festivals and other live events, long-distance collaborations over video and social media, and creative partnerships with more mainstream artists. But the most powerful force for longevity is education, and right now, it’s Aaron holding the key.

CRACKING THE CODE

“I want to make sure the leap from code to music is as small as possible and as clear and simple to as many people as possible,” said Aaron, a passionate advocate for unearthing the creative potential of programming languages. He spends his days as a researcher at the University of Cambridge in England and his nights performing live coding.

In 2012, Aaron created Sonic Pi, a simple yet powerful open-source programming environment designed to enable users at any level to learn programming by creating music and vice versa. Sonic Pi is used all over the world; it runs on any computer platform including Raspberry Pi, the $40 credit card-sized computer designed for DIY projects and for promoting computer science in schools and developing countries.

“Music really helps by wrapping the math concepts and computer science concepts into something that has direct meaning to kids, which is making music,” Aaron said. “And making the kind of music, hopefully, that they listen to on the radio or stream.”

The case for building these new learning paths to computer science is strong. Understanding basic programming improves logical thinking and provides a fundamental understanding of technology we use every day.

“Teaching people what coding is — how precise a language has to be for a computer to understand it — gives people an appreciation of an execution of semantics in a program, affordances of a system, interaction with a system,” said Aaron. “People are telling kids to learn how to program because they can become professional programmers. It’s like saying we should all do sports in school so we can become professional athletes. You don’t teach math because you’re training the future mathematicians. There’s a level of math that’s useful to all of our lives."

Sarah Jones is a writer for The Henry Ford Magazine. This story originally ran in the March-May 2017 issue.

computers, technology, music, by Sarah Jones, The Henry Ford Magazine

The Search for Home

Detroit Reacts to the Great Migration: Before the first World War, a majority of Detroit's African American population lived on the East Side and shared the area, known as Black Bottom, with white immigrant populations. At this time, relatively few African Americans, just 1.2% of the total population, called Detroit home. By 1930, the city’s African American population had grown by over 1,991%. The white immigrant population began to vacate the Black Bottom area and were quickly replaced with the growing population of African Americans attracted to the north by the promise of employment in Detroit’s booming auto industry and an escape from the rampant oppression of the south. As the African American population in Detroit increased, racial residential boundaries began to form, due in part to the stress on housing stock, as well as to outright discrimination in institutions such as employment and real estate.

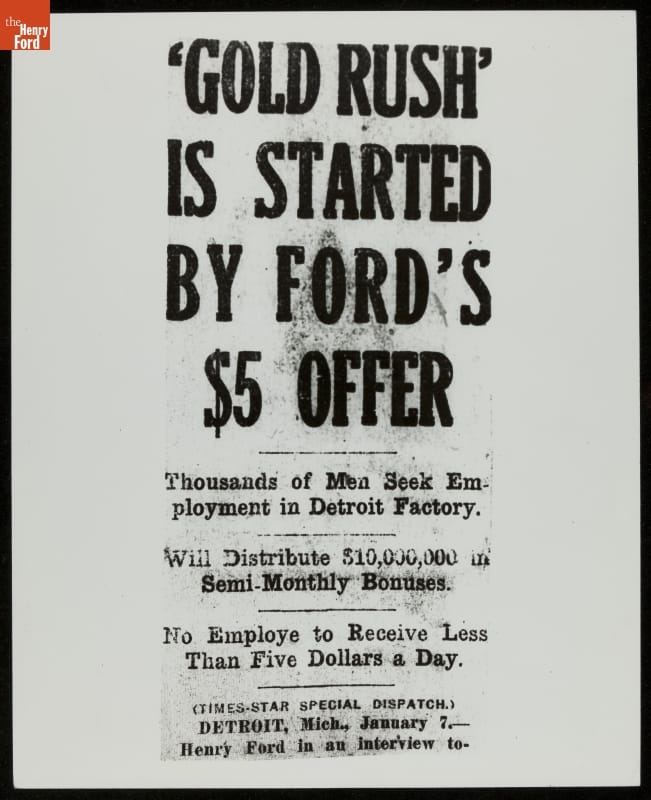

Photographic print - "Newspaper Article, "Gold Rush is Started by Ford's $5 Offer," January 7, 1914" - Ford Motor Company

The automobile industry and Henry Ford’s highly-publicized $5-a-day helped to draw people in great numbers to the Detroit area. However, for African American workers, reality often differed from their hopes and expectations in the north. While many of the automotive manufacturers did hire African Americans, it was almost always for the lowest paying jobs, such as in the janitorial department or the foundry. Ford Motor Company led the automotive industry in its hiring of African American workers by 1919. The company paid African American workers the same rate as their white counterparts and hired for a variety of positions, including skilled labor. Across the board, however, African American workers made less money than their white counterparts, and consequently, had less income for quality housing.

Photographic print - "Pickling Metal Crankcases and Other Parts to Remove Surface Impurities, Ford Rouge Plant, 1936" - Ford Motor Company Photographic Department

Discriminatory real estate practices played a significant role in the housing issues which plagued Detroit. Racially restrictive covenants, which legally ensured the sale of property to only white buyers, became increasingly common in Detroit. Even if a restrictive covenant was not in place, the Detroit Real Estate Board warned area realtors “not to sell to Negroes in a 100 percent white area,” thereby enforcing and perpetuating Detroit’s racial geography. Further, the practice of “redlining,” or the racial categorization of areas by their perceived financial risk in home insurance and mortgage lending, effectively shut out black homebuyers from the market. The practice extended to the lending of new mortgages, but also to home loans, leading to the inability to complete home repairs and, eventually, an abundance of blighted homes in black neighborhoods. In addition, real estate agents erroneously reported to white homeowners that the presence of black families in their neighborhoods would lower their property values. White homeowners, even those without ingrained prejudices against African Americans, certainly did not want their property values to lower, so rallied against any attempt by an African American homebuyer purchasing in their neighborhoods. The infamous story of African American Physician Dr. Ossian Sweet exemplifies the discrimination and mob violence experienced by those who attempted to move into white neighborhoods.

Discrimination in the workplace meant that African Americans, as a whole, made significantly less money than their white counterparts. Redlining practices forced them into racially-segregated neighborhoods and cemented their inability to access loans for mortgages or home repairs. Yet, the promise of the north continued to draw African Americans to Detroit. Without access to capital, increasingly-crowded neighborhoods became increasingly-deteriorated. At each turn, discriminatory systems excluded an entire population from quality housing. From these conditions, Charles H. Lawrence and his family departed Detroit in search of quality housing and a better life. He became the first African American to settle in Inkster, Michigan, and hundreds soon followed.

African Americans Settle in Inkster

The City of Inkster, also located in Wayne County, is approximately fourteen miles from downtown Detroit. Detroit Urban League President John Dancy fielded many housing inquiries from frustrated African American migrants to Detroit in the post-World War I period and beyond. Unable to locate sufficient housing in the City of Detroit, Dancy broadened his search outside the City with hopes that more rural areas would not have the same restrictive covenants and that lesser demand would persuade landowners to sell to African American buyers. In 1920, Dancy succeeded when he found amenable property owners in possession of 140 acres in rural Inkster. Although Inkster’s first African American residents’ settlement in Inkster preceded Dancy’s discovery, the 140 acres of available land enabled and impelled hundreds more African American families to move from Detroit to Inkster, despite the lack of a local government or basic public amenities like streetlights or sewer lines.

Clipping (Information artifact) - ""Henry Ford on Unemployment," 1932" - Detroit Free Press (Firm)

A Community Becomes a Project

Henry Ford was vocal about his disdain for institutionalized philanthropy. He wrote an entire chapter, entitled “Why Charity?” in an autobiography, and explained, “philanthropy, no matter how noble its motive, does not make for self-reliance…A philanthropy that spends its time and money in helping the world to do more for itself is far better than the sort which merely gives and thus encourages idleness.” Henry Ford’s brand of philanthropy was characterized by helping people help themselves. During the Great Depression, Henry Ford was called upon by the City of Detroit to provide aid because the City’s welfare offices were overwhelmed. Their argument, aside from civic responsibility, was that the City was not receiving taxes from Ford Motor Company (FMC’s factories were located outside Detroit) yet as many as “36 percent of the families receiving care from the City of Detroit were former Ford employees” in 1931. The public goodwill that Ford’s $5 a day policy brought was quickly dissipating. In 1931, Ford agreed to two philanthropic ventures; he provided a low-interest, short-term $5 million loan to the City of Detroit and essentially took the then-Village of Inkster under the Ford Motor Company’s auspices.

Photographic print - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

Photographic print - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

Photographic print - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

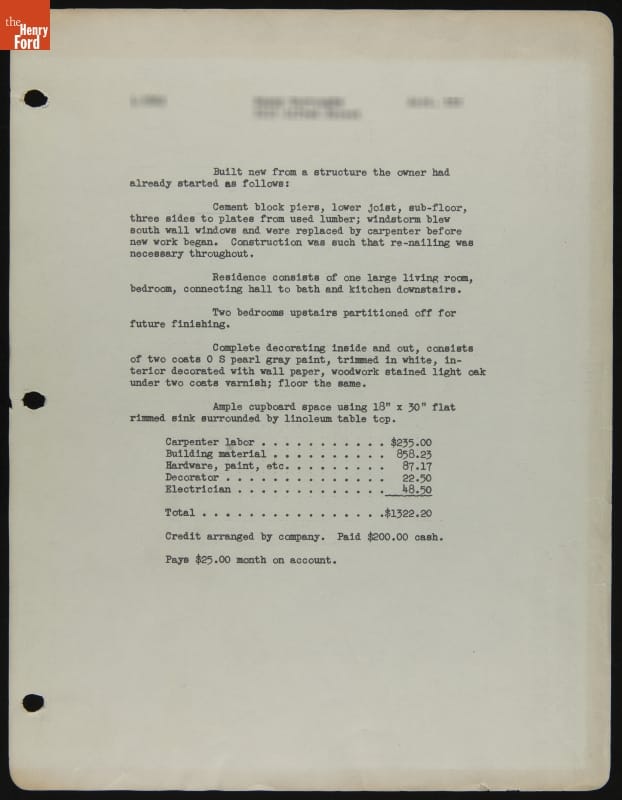

Report - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

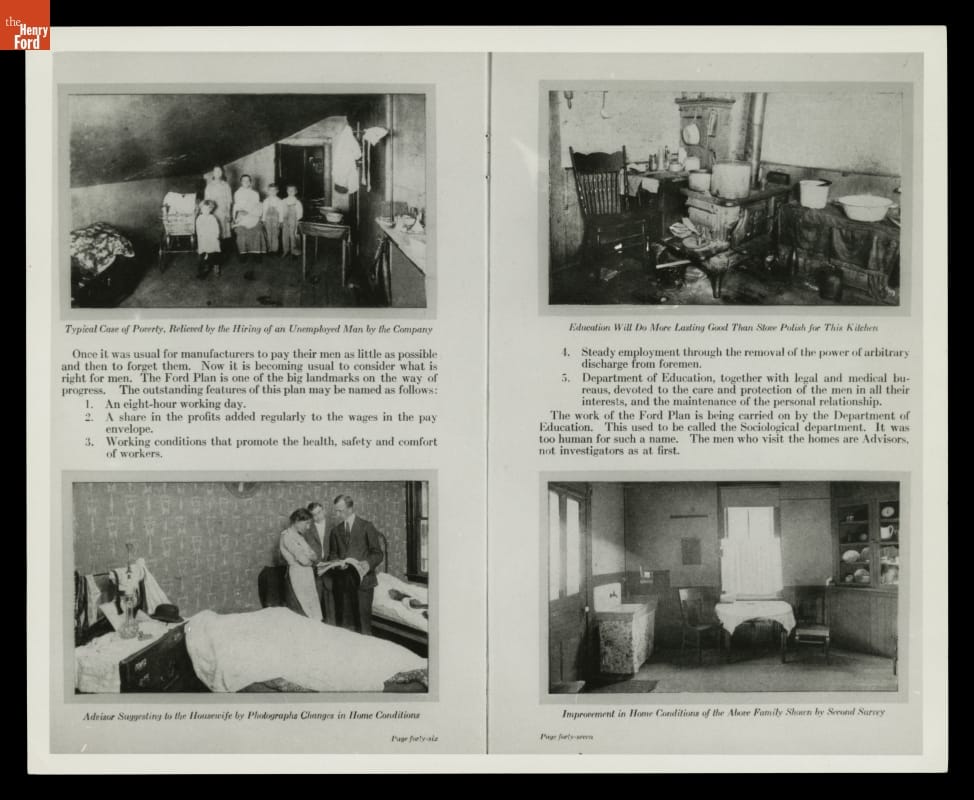

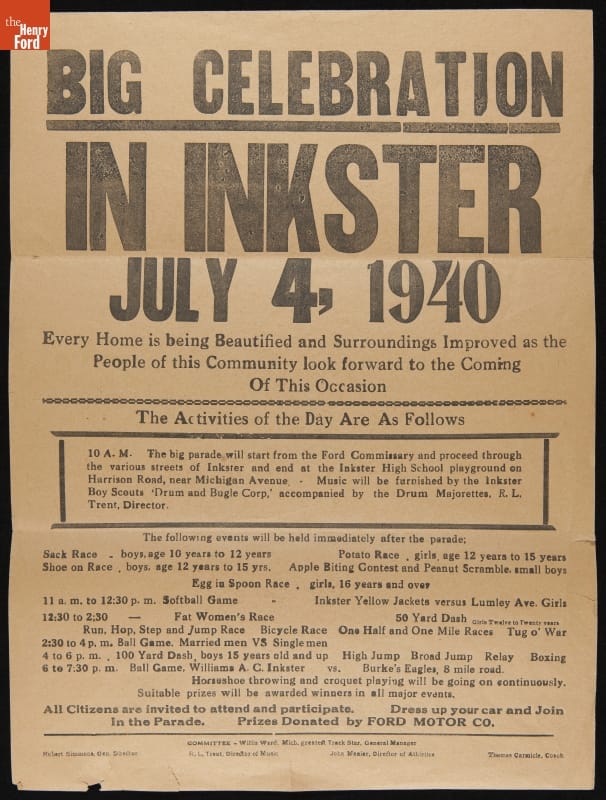

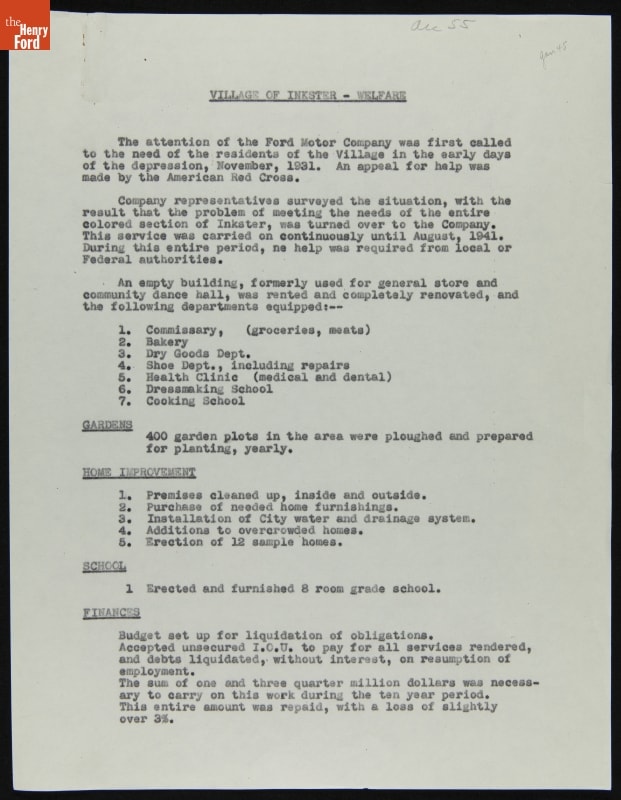

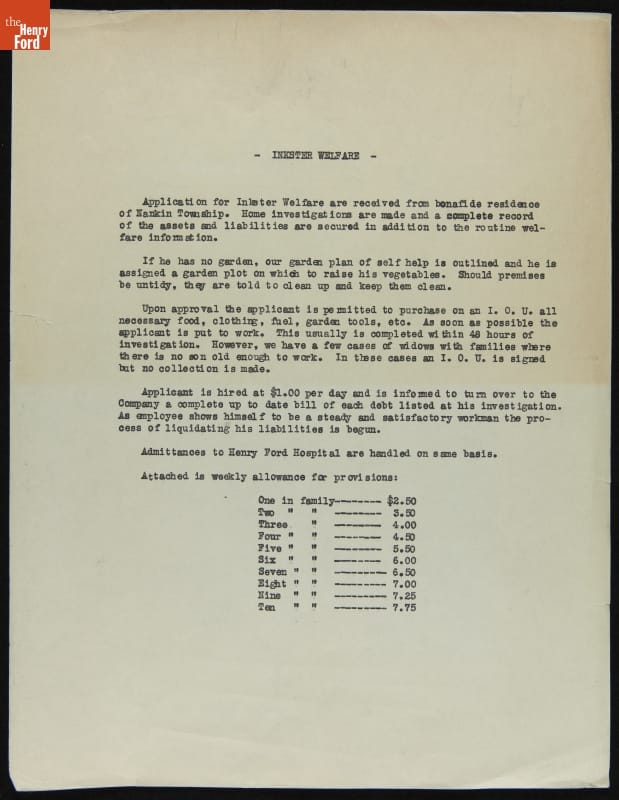

By 1931, a few years into the Great Depression’s hardships, the residents of Inkster were struggling. Unemployment and debt were high, public services had been cut, and many residences remained partially-completed, as the Great Depression halted progress in the young village. Controversially, Henry Ford placed FMC’s Sociological Department in charge of what became known as the Inkster Project. The Sociological Department was created in 1914 in order to manage the diverse workforce and ensure employee adherence to the company’s strict standards, which were paternalistic in nature and often crossed the home life-work life boundary. In Inkster, the Sociological Department immediately began implementing programs to comprehensively rehabilitate the village. A commissary, which sold high-quality, low-cost food and essential home goods, was established. Coal was distributed to those who needed it to heat their homes. Debtors were paid off, and a medical clinic and school were constructed. Homes deemed insufficient were rehabilitated. The inability to pay for these services was irrelevant; a type of “I.O.U,” repayable through Ford-provided work and wages, was enough to access all life’s necessities.

Photographic print - "Checking on Ford Employees Home Conditions, Views from "Factory Facts From Ford," 1917"

The Legacy of the Inkster Project

Although the Inkster Project was generally highly-regarded at the time, the FMC Sociological Department’s role was often overreaching. When agreeing to Ford’s aid, an Inkster resident was also agreeing to running their household as preferred by Henry Ford. Although his funds undoubtedly helped Inkster during the Great Depression, Ford’s motives were not entirely altruistic. Besides the much-needed public relations boost he received from the Inkster Project, he also was able to assert his influence and ideals on a community that largely had no choice but to accept his aid -- with all strings attached.

Broadside (Notice) - "Big Celebration in Inkster," July 4, 1940"

The Inkster Project’s legacy is complicated; many historians criticize Henry Ford’s paternalistic nature and the perhaps forceful imposition of his will onto the desperate, but others, including former residents of Inkster, praise Henry Ford for his aid. In her reminiscences, Georgia Ruth McKay explains that Inkster became a “jungle village changed into a city” during this period and that, “without his [Henry Ford’s] help, many would not have survived.” The Inkster Project was slowly phased out, but continued to operate in Inkster until 1941 when all programs were withdrawn.

Progress report - "Village of Inkster Welfare Report, 1931-1941" - Ford Motor Company

Report - "Village of Inkster Welfare Provision Report, circa 1936" - Ford Motor Company

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. In writing this piece, she appreciated the research and writings of Beth Tompkins Bates’ “The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford”, Thomas J. Sugrue’s “The Origins of the Urban Crisis; Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit,”, and Howard O’Dell Lindsey’s dissertation, “Fields to Fords, Feds to Franchise: African American Empowerment in Inkster, Michigan.”

20th century, Michigan, labor relations, home life, Henry Ford, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, Detroit, by Katherine White, African American history

Surprising Stories from IMLS Discoveries

While researching the many electrical objects being digitized as part of the Institute of Museum and Library Sciences grant, a few stories have stood out to me. These stories sometimes involve the people behind the scenes: manufacturers, inventors, etc., and other times are about how the object was used. Below are four such objects and their stories.

While researching the many electrical objects being digitized as part of the Institute of Museum and Library Sciences grant, a few stories have stood out to me. These stories sometimes involve the people behind the scenes: manufacturers, inventors, etc., and other times are about how the object was used. Below are four such objects and their stories.

This Jenney Electric Motor Company rheostat has uncovered an interesting story about the company’s namesake. It was designed by Charles G. Jenney who was awarded a patent for it in 1892. Jenney, originally from Ann Arbor, Michigan, moved to Fort Wayne, Indiana with his father to design and produce electrical equipment for the Fort Wayne Jenney Electric Light Company. On February 27, 1885, Jenney, who had been contracted to the Fort Wayne Jenney Electric Light Company by his father while still a minor, successfully petitioned to be removed from the company, and, a month later, he founded the Jenney Electric Light Company later the Jenney Electric Company. The Jenney Electric Company was demonstrating Jenney’s dynamos, arc lamps, and incandescent lamps by August that same year. This company was bought out and Jenney started again, this time with the Jenney Electric Motor Company in 1889 for which he produced electrical equipment like this rheostat, filed for more patents, and wired and lit the streets of Indianapolis.

Continue Reading20th century, 19th century, power, IMLS grant, electricity, by Laura Myles

Glass Gallery x2

With the Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery opening in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation last fall, Greenfield Village is the site for the next chapter in this exhibit's story.

The Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery is in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. It opened in October 2016. The Davidson Gerson Gallery of Glass is in Greenfield Village’s Liberty Craftworks District. Its grand opening is set for spring 2017.

Both galleries provide an in-depth look at the American glass story. The museum gallery focuses specifically on the studio glass movement of the 1960s, while the village gallery, supported by the Michigan Council for the Arts and Cultural Affairs, surveys the history of American glass, ranging from 18th-century colonial glass through 20th-century mainstream glass as well as studio glass.

Charles Sable, curator of decorative arts, was tasked with updating and reinterpreting The Henry Ford’s American glass collection. He envisioned creating an all-new gallery adjacent to the museum’s Glass Shop in the Liberty Craftworks District of Greenfield Village — a place to exhibit portions of the institution’s 10,000 glass artifacts currently in storage. His vision intersected with that of collectors Bruce and Ann Bachmann, who were seeking to donate their 300-piece studio glass collection.

According to Sable, the studio glass movement, which began in the early 1960s, is recognized as a turning point in the history of glass, as artists explored the qualities of the medium in a studio environment. Their goal was to create fine art. Evolving over a 20-year period, the movement matured in the 1980s with artists producing a myriad of unique works.

While other museums were interested in the Bachmann collection, it was The Henry Ford that garnered the collectors’ full attention and eventually their generous donation. “The Bachmanns had very specific criteria for their collection,” said Sable. “They were looking for an institution that was in an urban area, preferably in the Midwest where they live, had a large visitation, and was capable of exhibiting and maintaining the collection.

“As Bruce told me, it was a good marriage. He felt his collection would live here in perpetuity,” added Sable.

The story of the studio glass movement is now on permanent exhibition in the DavidsonGerson Modern Glass Gallery, which is located in the museum space that once showcased The Henry Ford’s silver and pewter collections. “Our exhibit is a deep dive into how studio glass unfolded,” said Sable. “It’s the story of the combination of science and art that created a new and innovative chapter in the history of glass.”

The exhibition also looks at the impact of studio glass on everyday life and includes a section on mass-produced glass influenced by studio glass and sold today by retailers such as Crate and Barrel, Pier 1 Imports and others.

Once the new Davidson-Gerson Gallery of Glass in Greenfield Village opens this spring, thousands of visitors will have an added opportunity to see larger-scale studio glass pieces from the Bachmann collection as well as the evolution of American glass.

DID YOU KNOW?

The Bachmann studio glass collection includes representation of every artist of importance in the movement, including Harvey Littleton, Dominick Labino, Dale Chihuly, Lino Tagliapietra, Laura Donefer and Toots Zynsky.

The gallery is a careful redesign of the McDonald & Sons Machine Shop in the Liberty Craftworks District.

BY THE NUMBERS

180: The number of glass artifacts on display in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation’s Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery.

155: The number of artists represented in the Bachmann studio glass collection.

300: The number of studio glass pieces in the Bachmann collection

Additional Readings:

- Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery

- Beyond Favrile: Louis Comfort Tiffany and American Culture

- Western Interactions with East Asia in the Decorative Arts: The 19th Century

- Tiffany and Art Glass

21st century, 20th century, The Henry Ford Magazine, philanthropy, Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, glass, decorative arts, art

Small Button, Big Message

In the “With Liberty and Justice for All” exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, you’ll see a number of Civil Rights–related buttons, including one from the 1963 March on Washington, one declaring “Black is Beautiful,” and one featuring a picture of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the slogan “Practice Nonviolence.” These all come from the Kathryn Emerson and Dr. James C. Buntin Papers, a collection we’ve recently been digging into.

Kathryn Emerson and Dr. James Buntin were interested and active in social causes such as welfare rights, Civil Rights, and education, among others, during the 1960s and 1970s, and the collection contains dozens of buttons that we’ve just digitized, including this one proudly declaring “Be Black Baby.” We’ve also recently digitized some of the couple’s clothing, books, and other materials.

Browse all of the digitized material from this fascinating and still-very-relevant collection by visiting our Digital Collections, and watch for an upcoming blog post from Curator of Public Life Donna Braden exploring Dr. Buntin’s library.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Civil Rights, Henry Ford Museum, African American history, by Ellice Engdahl, digital collections

Exposed Engine: 1913 Scripps-Booth Rocket Cyclecar

1913 Scripps-Booth Rocket

V-2 cylinder engine, air-cooled, 35 cubic inches displacement, 10 horsepower

Inexpensive cyclecars, as the name suggests, often used motorcycle engines like the V-2 in this Scripps-Booth prototype. The air-cooled motor meant there was no need for water or a radiator, while the splash lubrication system eliminated the necessity for an oil pump. The prototype’s engine is mounted with its crankshaft parallel to the rear axle, simplifying the belt connections between transmission and wheels.

1910s, 20th century, Henry Ford Museum, Engines Exposed, engines, Driving America, cars, by Matt Anderson

Another Thought on NAIAS 2017

I’ve already shared some thoughts on the 2017 North American International Auto Show, but one important new car wasn’t yet revealed during my visit last week. Of course, I’m talking about the LEGO Batmobile from Chevy.

My tastes in bat-transportation run more traditional, but Chevy has something going for it here. The LEGO Batmobile’s 20,000-horsepower rating makes it eight times as powerful as the Goldenrod land speed racer. Likewise, the V-100 engine’s 60.2-litre displacement is more than eight and a half times what it took for the Mark IV to win at Le Mans fifty years ago. The LEGO Batmobile’s styling achieves that rare combination of aerodynamic and exquisite, certain to turn heads on every street corner. Be sure to order the optional bat hood ornament – superior to anything by Lalique. (Besides, everybody knows that bats eat dragonflies.)

Continue Reading21st century, 2010s, toys and games, NAIAS, Michigan, LEGO, Detroit, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson

Exposed Engine: 1930 Ford Model A

1930 Ford Model A

Inline 4-cylinder engine, L-head valves, 201 cubic inches displacement, 40 horsepower

Painting engine blocks is a long-standing tradition among automakers. In the 1960s, Ford favored blue while Chevrolet preferred orange. But green was Ford’s color of choice when this Model A came off the line. The black enameled pipe, running diagonally along the block just below the carburetor, returns surplus oil from the valve chamber back to the crankcase.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, 20th century, 1930s, Henry Ford Museum, Ford Motor Company, Engines Exposed, engines, Driving America, cars, by Matt Anderson

Mrs. Cohen: A Fashion Entrepreneur

Life is often a juggling act of work, play and family. While current-day clothiers experience the trials and tribulations of being small-town entrepreneurs in the big business of fashion, more than 100 years ago many women were facing similar circumstances, leaning on their sense of style to furnish a living.

In the late 1800s, Elizabeth Cohen had run a millinery store next to her husband’s dry goods store in Detroit. When he died and left her alone with a young family, she consolidated the shops under one roof. Living above the store, she was able to run a business and earn a living while staying near her children.

Cohen leveraged middle-class consumers’ growing fascination with fashion, using mass-produced components to create hats in the latest styles and to the individual tastes of customers. To attract business, resourceful store owners like Mrs. Cohen displayed goods in storefront windows and might have advertised through trade cards or by placing advertisements in newspapers, magazines or city directories.

“While Mrs. Cohen was more likely following fashion than creating it, it did take creativity and design skill,” Jeanine Head Miller, curator of domestic life at The Henry Ford, said of Cohen’s millinery prowess. “She was a small maker connecting with local customers in her community — a 19th-century version of Etsy, perhaps, but without the online reach.”

And she certainly gained independence and the satisfaction of supporting her family while selling the hats she created from the factory-produced components she acquired. “People can appreciate the widowed Elizabeth Cohen’s balancing act,” added Miller, “successfully caring for her children while earning a living during an era when fewer opportunities were available to women.”

Jennifer LaForce is a writer for The Henry Ford Magazine. This story originally appeared in the June-December 2016 issue.

19th century, women's history, The Henry Ford Magazine, shopping, Michigan, making, hats, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, fashion, entrepreneurship, Detroit, design, Cohen Millinery, by Jennifer LaForce