Remembering Lillian Schwartz

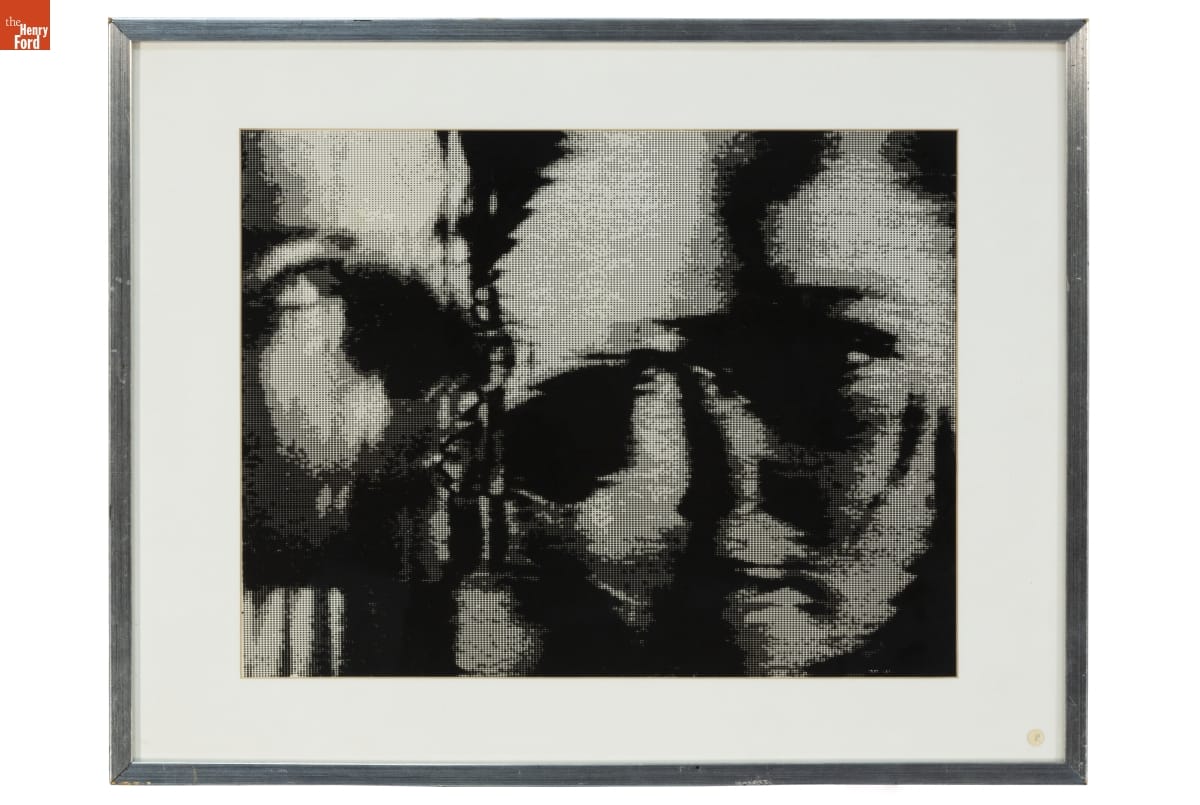

Self Portrait by Lillian F. Schwartz, circa 1979 / THF188557

On October 12, 2024, The Henry Ford was saddened to receive news of Lillian Schwartz's passing. Lillian was a visionary multimedia artist — an early adopter, innovator, and life-long learner in creative computing and digital art. At Bell Laboratories, she held the role of "resident visitor" from 1968-2002, where she created her celebrated films and videos. At the Labs, she described herself as a "morphodynamicist" and "pixellist." Max Mathews — director of Bell Labs' Acoustical and Behavioral Research Center — supported and advocated for Lillian, calling her "the brightest genius" he had ever met. Arno Penzias, a Nobel laureate for his co-discovery of the Big Bang Theory, credited her work as "establishing computers as a valid and fruitful artistic medium." There is no question that Lillian helped to define and expand the boundaries of digital creativity beginning in the late 1960s — a time when the very validity of computer-mediated art was in question.

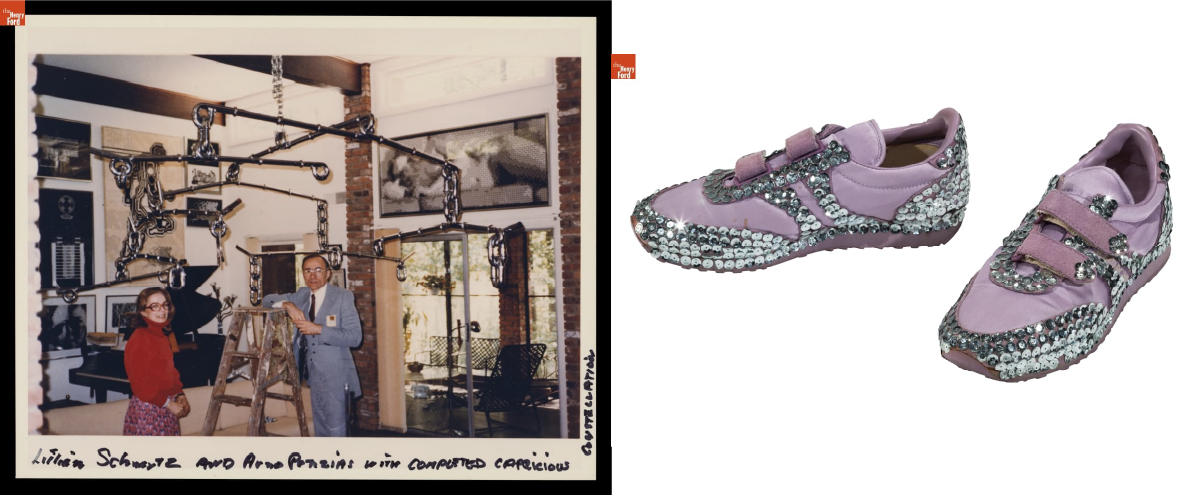

Left: Lillian Schwartz and Arno Penzias with the Capricious Constellation Sculpture, circa 1984 / THF705948

Right: Custom bedazzled Jordache sneakers made and worn by Lillian, circa 1984 / THF191767

In 2021, thanks to a generous donation by the Schwartz family, the Lillian F. Schwartz and Laurens R. Schwartz Collection found a permanent home at The Henry Ford. This collection contains thousands of objects documenting her life and art practice, spanning her childhood to late career. Lillian's expansive career is represented through her iconic films and videos, 2D artwork and sculptures, personal papers, computer hardware, and film editing equipment.

Since this acquisition, staff at The Henry Ford have been diligently conserving, restoring, organizing, digitizing, and interpreting this collection to improve accessibility and ensure ongoing recognition for Lillian's contributions. In 2023, I was honored to be deeply immersed in this collection while curating Lillian Schwartz: Whirlwind of Creativity. This retrospective exhibition provided a holistic portal to her life and artistic practice. Many of the exhibit's early "analog" and 2D works showed a clear lineage to the aesthetic values seen in her film and digital art that would follow.

Exhibition view of Lillian Schwartz: Whirlwind of Creativity, which was open at The Henry Ford from March 2023-March 2024. Image by Staff of The Henry Ford.

Since acquiring this collection, The Henry Ford has collaborated with major museums, institutions, and educators by providing loans of her work for exhibitions, film festivals, and public programs — ensuring the continuation of her presence and legacy at a global scale. Notably, The Henry Ford has provided loans to international venues including: Venice Biennale, LACMA, ZKM Centre for Art & Media, Mudam Luxembourg, Tate Modern, Buffalo AKG, the Computer History Museum, and many more.

Left: Lillian and Jack J. Schwartz, circa 1946 / THF704695

Right: Lillian Schwartz with a Flowering Plum Tree in Japan, 1948-1950 / THF705897

Lillian was born in Cincinnati in 1927 to Russian and English immigrant parents. Her large family faced economic challenges and, as Jewish people, became the targets of antisemitism. In 1944, Lillian applied to join the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps — a program designed to address the WWII nursing shortage. Lillian struggled with nursing people but enjoyed mixing medicines, painting murals in the children's ward, and making sculptures from plaster supplies intended for broken bones. Here, Lillian realized she was an artist, not a nurse. During this time, she met her future husband, Jack Schwartz, a doctor in training. They were married in 1946. In 1949, Lillian and her newborn son Jeffrey traveled across the Pacific Ocean by U.S. Army transport ship to be reunited with Jack, who was stationed at a hospital in Fukuoka, Japan. Just weeks after this journey, Lillian contracted polio and was quarantined; she worked diligently for months to overcome the worst of her paralysis, but upon her return, she continued to face health issues, which she referenced in her work.

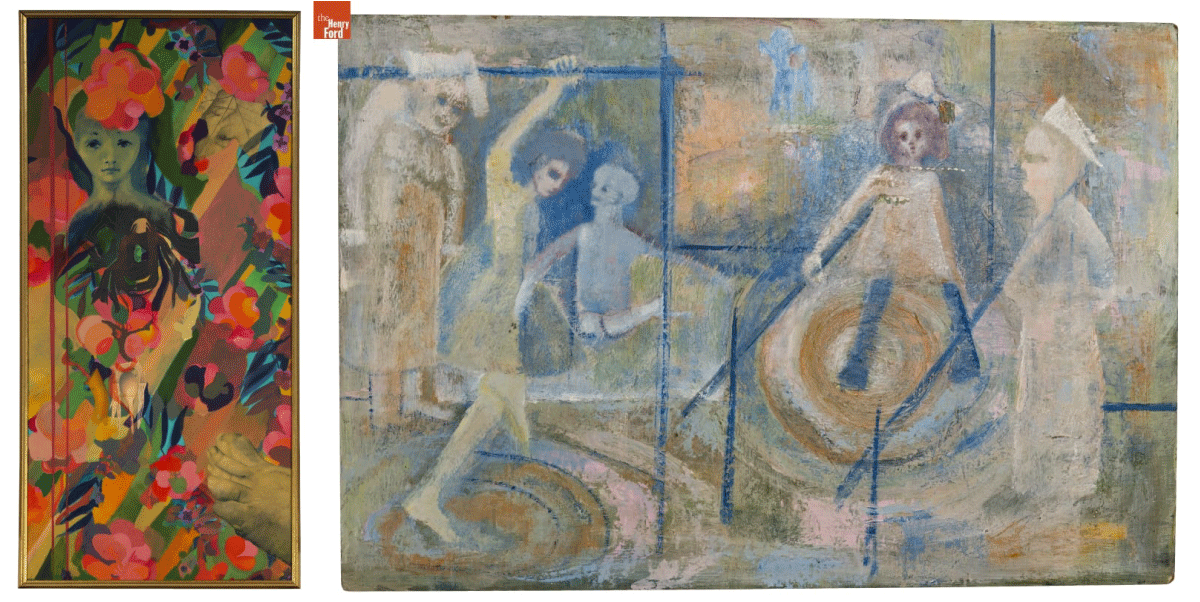

Many of Lillian's earliest paintings have childhood, motherhood, and family themes. Other times, they reflect traumatic events that Lillian faced. Left: Lady with Foot,' 1962 / THF190937

Right: After Polio,' circa 1950 / THF193129

In October 1968, Lillian received news that her kinetic sculpture — Proxima Centauri — had been selected by curator Pontus Hultén for an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, "The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age." It was a breakthrough moment in her career.

Lillian met the scientist Leon Harmon at the MoMA opening, and he invited her to visit his workplace, Bell Laboratories. This fateful meeting led to Lillian's introduction to the people, equipment, and software integral in creating her first computer films. In her unpublished memoir, Lillian recalls: "When I first saw Leon Harmon at the opening reception of the 'Machine' exhibition, he was on his hands and knees peeking under the pad that covered the mechanism that triggered my sculpture to move up and down. When he looked up, he saw me standing in front of his computer-generated nude [Studies in Perception I (Computer Nude)]."

Lillian Schwartz with ‘Proxima Centauri’ Globe, 1968-69. The globe that Lillian used was originally designed to be a municipal streetlamp cover. / THF705911

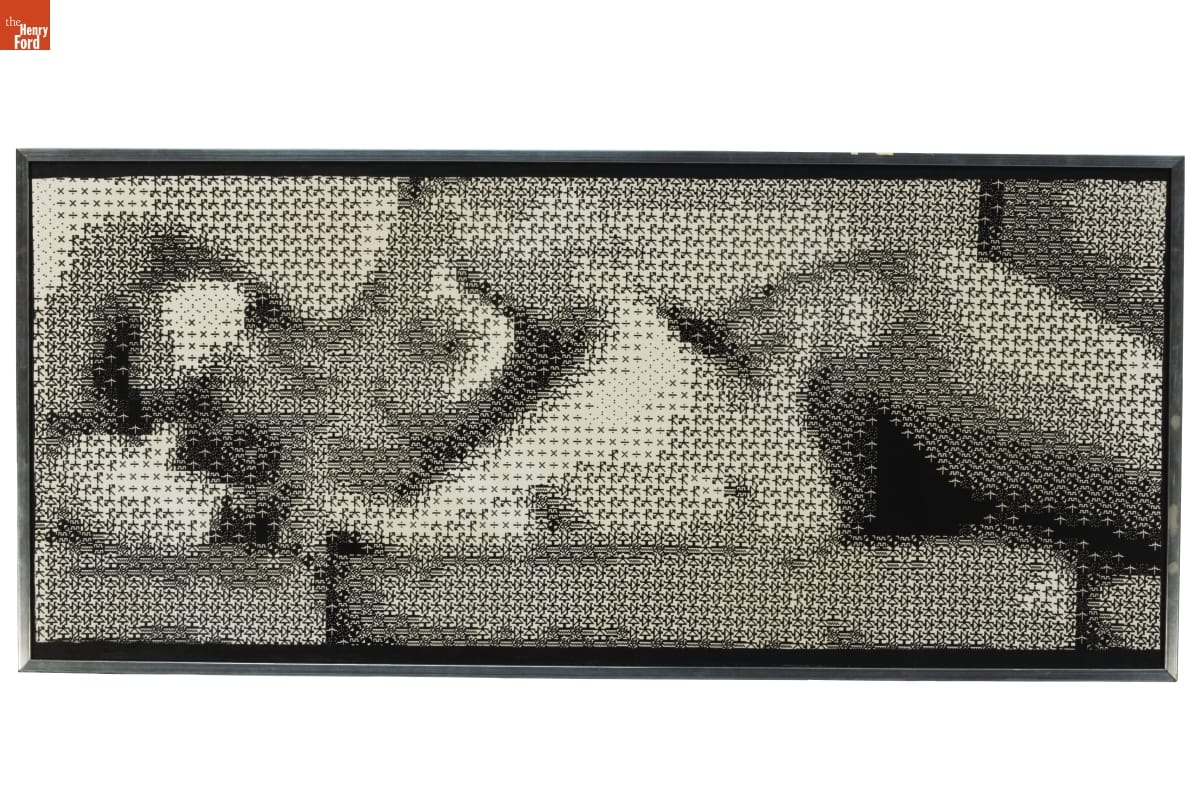

Studies in Perception I (Computer Nude) by Leon D. Harmon and Kenneth C. Knowlton is considered to be the first ‘digital nude.’ It was shown in the same MoMA exhibit as Proxima Centauri / THF188553

Lillian's youngest son and frequent collaborator Laurens remembers how he and Lillian "explored trash in the Bowery, bringing back wire, motors, and a globe that had been a streetlamp cover. But Lillian also created new tools and media. In 1960, she convinced the owner of a plastics factory to let her use it at night, moving rods to shape abstract [sculptures]. She built kinetics using metal frames lit inside to highlight the colors and movement of liquids through tubing and receptacles she bought from a medical supplier."

To prepare for the exhibit, our conservation team restored several kinetic sculptures that had not been exhibited in decades, including Proxima Centauri and World’s Fair, shown here. / THF370299

The kinetic sculpture referenced in this memory is World's Fair — a mock-up that Lillian created to propose a 70-foot-tall water sculpture for Expo 70 in Osaka, Japan. The sculpture was never built at full scale. The spiraling glass tubes in this version were given to her by a chemist planning to throw them in the trash. Lillian imagined how they could be filled with color and light to create the illusion of multiple colors. In her unpublished memoir, she described the process of finding the pigments to meet her vision: "Since I could not find the right green I wanted, I emptied [my husband Jack's] Creme de Menthe from the liquor cabinet. Of course, Jack was not happy. Even worse, I took all the red cough syrup samples from Jack's [medical] office. Not as expensive, but not the right thing to do."

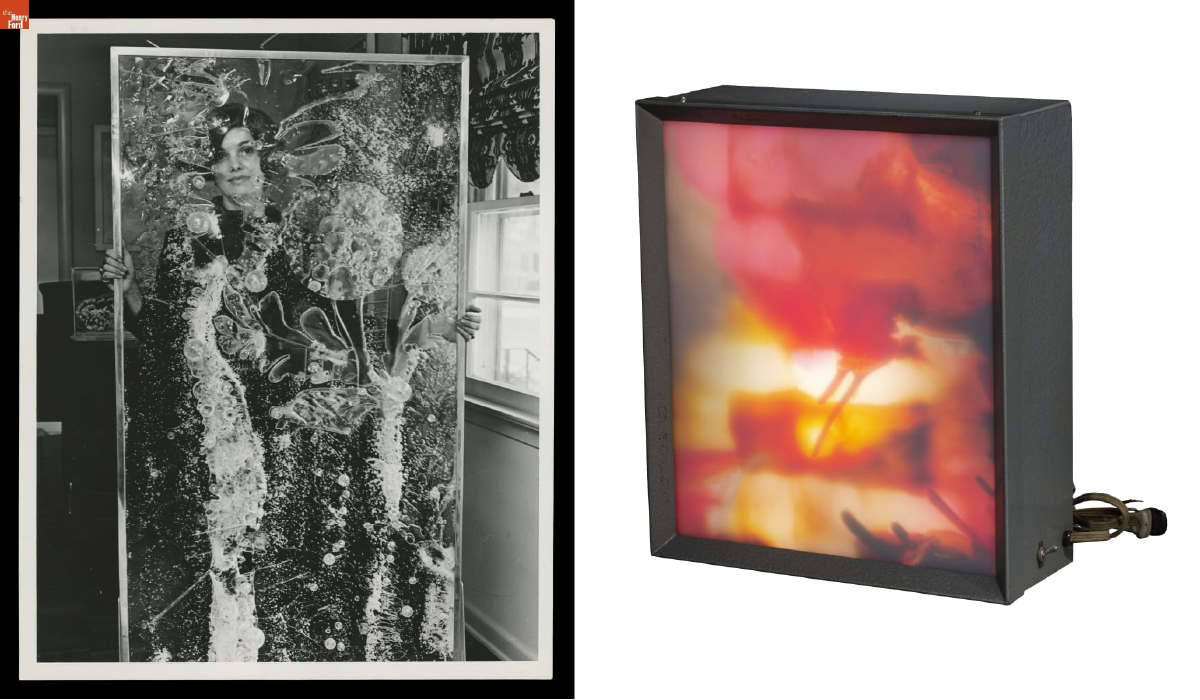

Left: Lillian Schwartz looking through one of her acrylic panels, 1968 / THF706047

Right: Illuminated Light Box by Lillian F. Schwartz, 1966 / THF188459

Lillian also created large cast acrylic resin sculptures. Once the resin hardened, she used a blowtorch to melt and change the plastic, sometimes gluing on extra material or using pigment to add color. She brought many of her sculptures and paintings to life by introducing sound, light, and electronic sensors. She called these works "electric paintings." Even her non-digital and kinetic works — screenprints hung on a wall or sculptures sitting static on a pedestal — clearly show Lillian's desire to create motion, eventually leading to the trailblazing computer films she would make at Bell Laboratories.

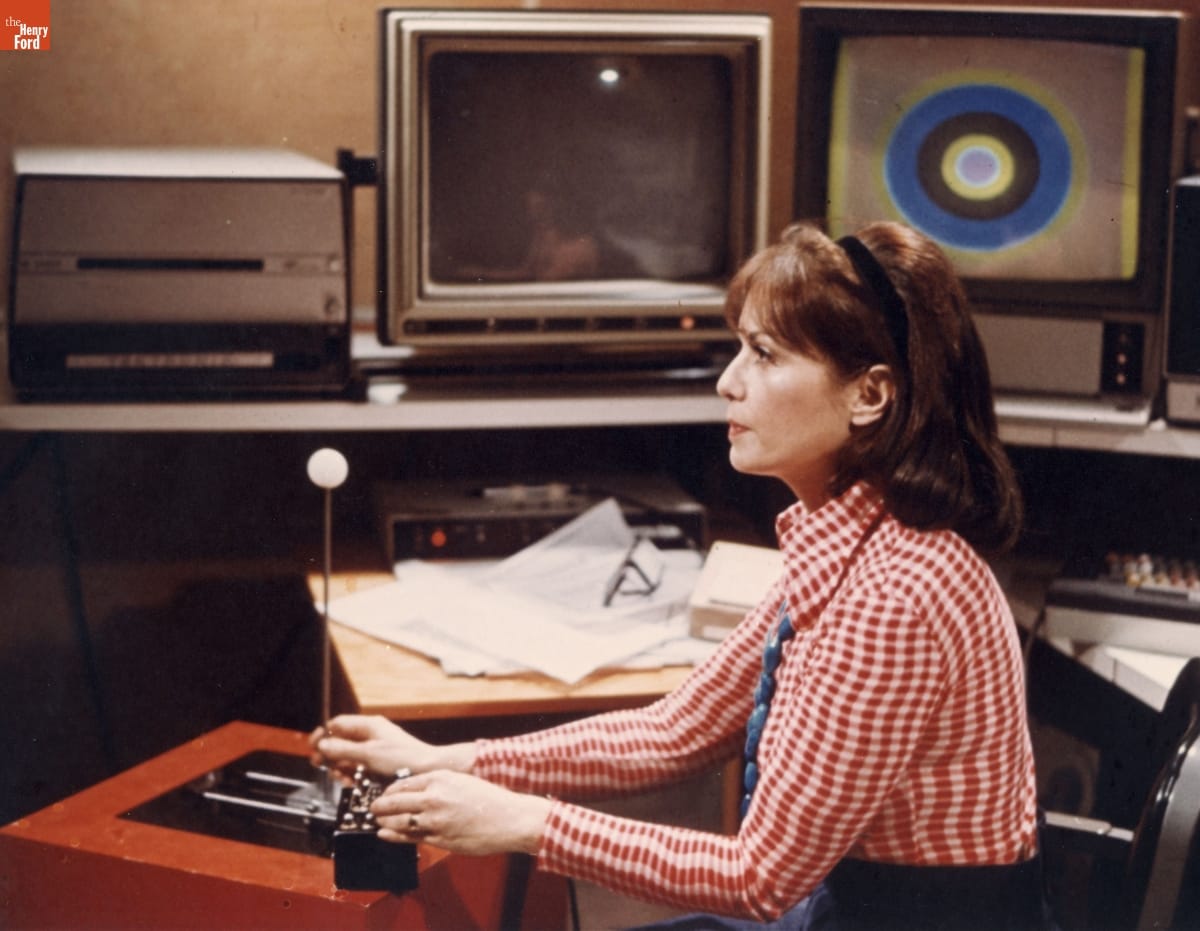

Lillian Schwartz photographed at work at Bell Laboratories by Gerard Holzmann, circa 1975 / THF149836

By gaining an invitation to Bell Labs, Lillian was in a rare and privileged position at one of the world's most revered research facilities. On her first day, she was introduced to the large mainframe computers and bespoke software that would lead to her first 2D digital artworks and computer-mediated films. On lunch breaks in the cafeteria, she formed fruitful collaborations with scientists. As she wandered the halls on breaks, she peered through open doors and was invited in for demonstrations of cutting-edge technology. With permission, she scavenged toss-off material from the trash to use in her own work. At night, she attended math, logic, and computer programming courses at the New School.

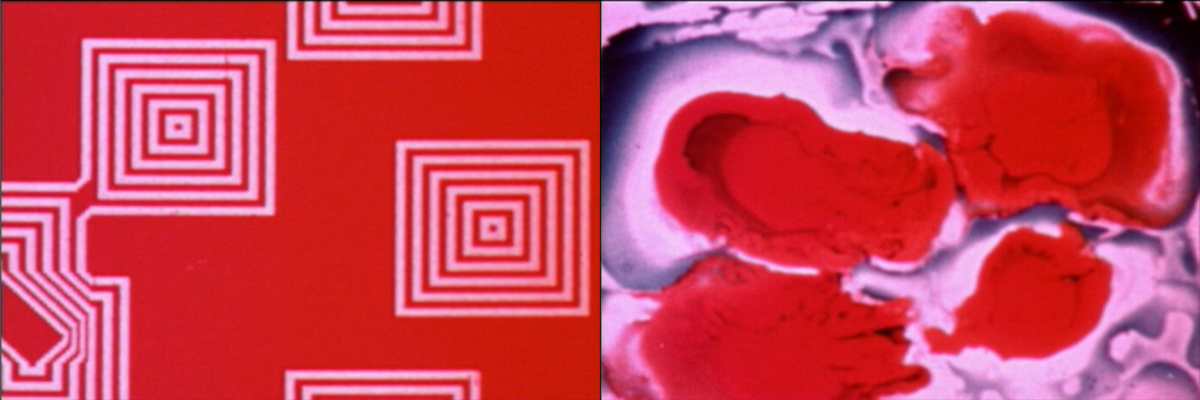

Digital born (left) and hand painted (right) stills from Pixillation, 1970 / THF701620 & THF701618

In 1969, Lillian received a $250 grant from AT&T Bell Laboratories to begin creating her first film, Pixillation. Given the limitations of 1960s computers, the process was time-consuming and frustrating. After several weeks of work, she had mere seconds of footage, so found creative ways to meet her deadline. She smeared and dropped paint onto glass to create abstract patterns, drawing her finger through the pigment to mimic the pixelated squares generated by the computer. She used a microscope to photograph growing crystals. She reshot the computer footage on an optical bench, adding color and motion. A soundtrack by Gershon Kingsley was added, which was crucial in and of itself for being composed on a new electronic instrument — the Moog synthesizer. By 1970, Pixillation was finally complete. Today, this film continues to be hailed as a masterwork of experimental film with its hypnotic and chaotic blend of computer-born and hand-painted imagery. Many awards and many films followed, a selection of which are visible in our Digital Collections.

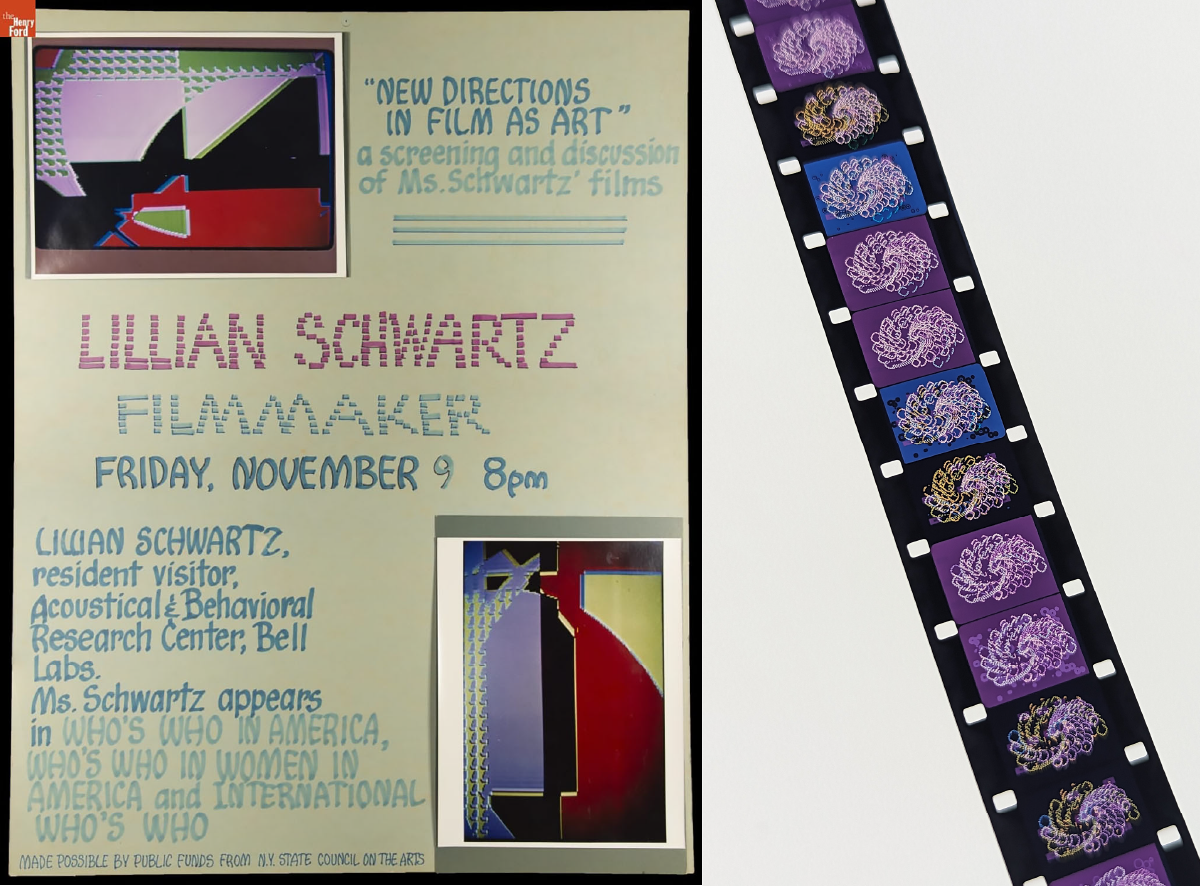

Left: Advertisement for a screening of Lillian’s work / THF628917

Right: A view of one of Lillian’s films, currently undergoing restoration. Photo by Kristen Gallerneaux.

Lillian saw computers as exciting tools full of possibility, but her peers also described her as having a healthy sense of "technological ingratitude." In her most playful and impatient moments, she sought out the limitations of technology — embracing its glitches, feedback, and happy mistakes. She described this impulse: "…the machine had to keep pace with me — just as I learned that I had to grow with the machine as its scientifically oriented powers evolved."

In her 2013 oral history with the Computer History Museum, she shared a potent memory that foreshadowed her later life as a filmmaker: "My story was as long as the pavement in front of my house. [...] When I had drawn as far as I could, I ran back to my house, sat on a step and looked at the pictures in my head to see the rest of the story." Lillian will be missed immensely, and we at The Henry Ford are honored to be stewards of her legacy.

Kristen Gallerneaux is the Curator of Communications & Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

Facebook Comments