Social Reform, Design and Craft at the Turn of the 20th Century: The Saturday Evening Girls, The Paul Revere Pottery and Clara Ford

The story of the Saturday Evening Girls (S.E.G.) is a compelling story of female empowerment in the early 20th century. The women who founded and the girls who became members of the S.E.G. — many of them immigrants of Jewish and Italian heritage — strengthened one another’s lives through social activities, education and artistry that built self-esteem, leadership qualities and wage-earning skills.

Daffodil centerpiece bowl, designed by Edith Brown, decorated by Sara Galner, dated March 1914 / THF193475

The roots of the story are found in turn-of-the-20th-century Boston, specifically an area where many immigrants settled called the North End. By the late 19th century, the area was a slum, consisting primarily of multistory tenement housing and light-manufacturing shops. Living conditions were generally rough, with families lacking private baths and central heating in their apartments. It was literally a hand-to-mouth existence in the first decade of the 20th century. Children of immigrants attended school if their parents could afford it, with many leaving before they got to high school, having to work to contribute to their family's income.

The North Bennet Street Industrial School

One of the few sources of assistance available to residents of the North End was the North Bennet Street Industrial School, which served as a settlement house and vocational school. The School dates to the 1880s and is still functioning as a neighborhood vocational school. Here is a link to its web site. Settlement houses developed from English charities in the late 19th century. The essential idea was to educate those in need, through education and work skills, so that they could help themselves out of poverty. The earliest and most famous American settlement house was Chicago’s Hull House, founded in 1889 by social reformers Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. American settlement houses tended to focus on assimilating immigrants in addition to the educational and vocational mission.

Edith Guerrier and the North Bennet Street School

It was into the North Bennet Street School that a young, idealistic woman named Edith Guerrier arrived in 1892. Guerrier (1870-1958) was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and spent significant time with her mother’s relatives, who introduced her to the literature and philosophy of Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Bronson Alcott. Guerrier graduated from the Vermont Methodist Seminary and Female College in Montpelier in 1891. With aspirations of becoming an artist, Edith next enrolled in the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. There, Guerrier met her lifelong friend and partner, Edith Brown (1872-1932), while both were sketching in the museum’s galleries. They quickly became inseparable, forming a lifelong partnership. Guerrier soon realized that she wouldn’t become an artist like Brown. So, to make ends meet, Guerrier got a job at the North Bennet Street School, first in the nursery.

By the mid-1890s, she was put in charge of the girls reading room, and she soon realized that her future was sharing the knowledge of literature with these immigrant Italian, Jewish and Irish girls. As she says in her autobiography, “I argued somewhat as follows, ‘I know life has far more to offer than I have yet found. Undoubtedly these girls feel the same way about it. Perhaps we can find together the key to some secret garden in which we can profitably enjoy ourselves.'”

In 1899, Guerrier officially became employed by the Boston Public Library and was assigned to the North End Branch, located inside the North Bennet Street School. From this vantage point, she started a series of nightly reading groups, Monday Evening Girls, Tuesday Evening Girls, etc., all the way up to the Saturday Evening Girls. The girls in the S.E.G. were the oldest, and it was considered the most prestigious of the reading groups. Girls graduated into it from the other groups. They produced their own newsletter, called the S.E.G. News, to which Guerrier was a regular contributor. The S.E.G. members adored Guerrier and remembered her inspiration for many decades with regular reunions. In fact, the S.E.G. News continued into the 1960s.

Guerrier and Brown Found the Saturday Evening Girls and Paul Revere Pottery

By 1905, Guerrier and Brown became acquainted with some of the philanthropists funding the North Bennet Street School, specifically Helen Osborne Storrow (1864-1944), who took a great interest in the S.E.G. Most importantly for our story, Storrow sent the two Ediths on a trip to Europe during 1907 and 1908. Many sources say that during their time in Europe, the Ediths conceived the idea of a pottery for the S.E.G. group. Other sources state that they secured a used pottery wheel from the Merrimac Pottery and experimented with the idea of a pottery. Whatever the origins, we know that in 1908, Storrow purchased a building for the reading groups on Hull Street in the North End. The pottery was in the basement, a retail store called the Bowl Shop was on the first floor and various reading clubs were on the upper floors. Brown and Guerrier called it the Paul Revere Pottery as it was literally in the shadow of the Old North Church, celebrated in the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem. The nonprofit pottery was based on the notion that it would teach young women principles of business and provide them with an independent income.

Designs and Significance of the Pottery

Brochure for Paul Revere Pottery, about 1930 / THF295607

Child’s “motto” bowl, designed by Edith Brown, decorated by Fannie Levine, “Early to Bed & Early to Rise, Makes a Child Healthy & Wise,” dated January 1909 / THF193476, THF193478

Trivet, designed by Edith Brown, decorated by Edith Brown, dated July 1928 / THF198456, THF198455

The designs found on the pottery came from Edith Brown, who drew on her education at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and her experience as a children’s book illustrator. The design vocabulary included stylized images of birds, farm animals, landscapes and rural scenes, all outlined in heavy black lines. This technique is called cuerda seca, where thin bands of a color-stained wax are applied to maintain color separation between glazes during firing. They leave behind "dry cords" of unglazed clay, in this case the black outlines. This was helpful in keeping the glazes from bleeding together, especially in the hands of young women who were learning the artistry of decorating ceramics. The dark outlines are reminiscent of Edith Brown’s design source, the English illustrator Walter Crane, a prominent member of the Arts and Crafts Movement, which espoused the social goals inherent in the Saturday Evening Girls club and Paul Revere Pottery.

The Arts and Crafts Movement was not only an aesthetic style but a philosophy that encouraged handcraftsmanship, the integration of art into everyday life and healthy working conditions. Adherents believed that creating art could improve a person both morally and spiritually. These immigrant girls created beautiful pots by hand while working in a clean, safe environment for decent hours and decent pay. Each worker had flowers for inspiration at her desk; volunteers would frequently read literature, plays or newspapers, and each girl was allowed to sign and date her own work.

A Decorator at the Paul Revere Pottery, about 1930 / THF278727

Between 1909 and 1914, the pottery became a success, critically and financially. The Boston Society of Arts and Crafts, an artisan group, elected Edith Brown to craftsman status in 1909 and promoted her to master craftsman in 1913. The Paul Revere Pottery as an organization achieved mastership in the society by 1917. Edith Guerrier opened a store on Boston’s prestigious Boylston Street in 1911, and the pottery was sold in retail outlets in New York and Chicago. By 1911, 12 young women were working full time as decorators, while 60 were devoting an hour a week to maintaining and running the pottery.

Interior of Paul Revere Pottery brochure, about 1930 / THF295609

Tea caddy with the initials of the owner, designed by Edith Brown, unknown decorator, dated November 1921 / THF198448, THF198449

In addition to the retail outlets, the public could custom-order pieces by mail and with initials and/or names. A good example is this tea caddy with the owner’s initials above the bunny. This was a selling point for children’s breakfast sets, which were very popular.

The Girls

Daffodil centerpiece bowl, designed by Edith Brown, decorated by Sara Galner, dated March 1914 / THF193474

There were many girls involved with the pottery over the years. The most celebrated of these was Sara Galner (1894-1982), who came up through the reading clubs and worked full time at the pottery, eventually becoming a salesperson and manager before her marriage in 1921. What is so exceptional about Galner’s work is that she took Edith Brown’s designs as a template and embellished them, making them her own beautiful works of art, such as the centerpiece above. Galner was featured in the groundbreaking exhibit, Sara Galner, The Saturday Evening Girls, and the Paul Revere Pottery at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 2006. Here is a link to its web site.

Child’s “motto” bowl, designed by Edith Brown, decorated by Lili Shapiro, “O Don’t Bother Me" Said the Hen with One Chick,” dated February 1910 / THF193479, THF193480

Another important artist was Lili Shapiro (1894-1978), whose early “motto” bowl is seen above. After Sara Galner left the pottery, Lili Shapiro took her place, essentially managing the organization until it closed in 1942. Like Galner, Shapiro was an accomplished artist, and her work is also prized by collectors and museums.

Maturity and Evolution

Garden at the Paul Revere Pottery, Brighton, Massachusetts, about 1930 / THF278731

A man holds a piece of pottery in the garden of the Paul Revere Pottery, about 1930 / THF278729

Catalog for the Paul Revere Pottery, about 1930 / THF295603

In the summer and fall of 1915, the house on Hull Street in the North End was sold and the proceeds used to purchase land on a hilltop in suburban Brighton, Massachusetts. As these images show, once the new building was completed, the pottery and an apartment for the Ediths were now in an idyllic garden setting, very much in keeping with the Arts and Crafts Movement’s ideals. The new plant was built with the continuing support of Helen Storrow, who maintained a lifelong interest in the enterprise. In 1916, the pottery was incorporated as the Paul Revere Pottery. Interestingly, the S.E.G. name continued to appear on ceramic pieces until about 1921, sometimes in addition to a stamp for the pottery.

Brochure for Paul Revere School of Ceramics, about 1930 / THF295612

Edith Brown started the Paul Revere Pottery School of Ceramics around 1926 as a means of keeping the pottery going financially. By the 1920s, nearly all the girls of the Settlement House period were married with families. The two Ediths continued the pottery, but its greatest days were behind it.

Edith Guerrier became a national figure in libraries, working for the federal government during the First World War and traveling around the nation. Following the war, she returned to Boston and eventually became the head of circulation for the Boston Public Library. She is noted as a major theorist in the social history of library science.

Clara Ford and the Paul Revere Pottery

Letter from Edith Guerrier to Clara Ford, June 29, 1936 / THF278733

In 1932, Edith Brown died of what was described as a “long illness.” Lili Shapiro took over the operation of the pottery, but Edith Guerrier was determined that the enterprise remain relevant. She recognized the interest of Henry and Clara Ford in reviving traditional craft and, in that light, suggested that they purchase the pottery and move it to the historic Wayside Inn in South Sudbury, Massachusetts, owned by the Fords, or to Greenfield Village, what she called the “Dearborn Village.”

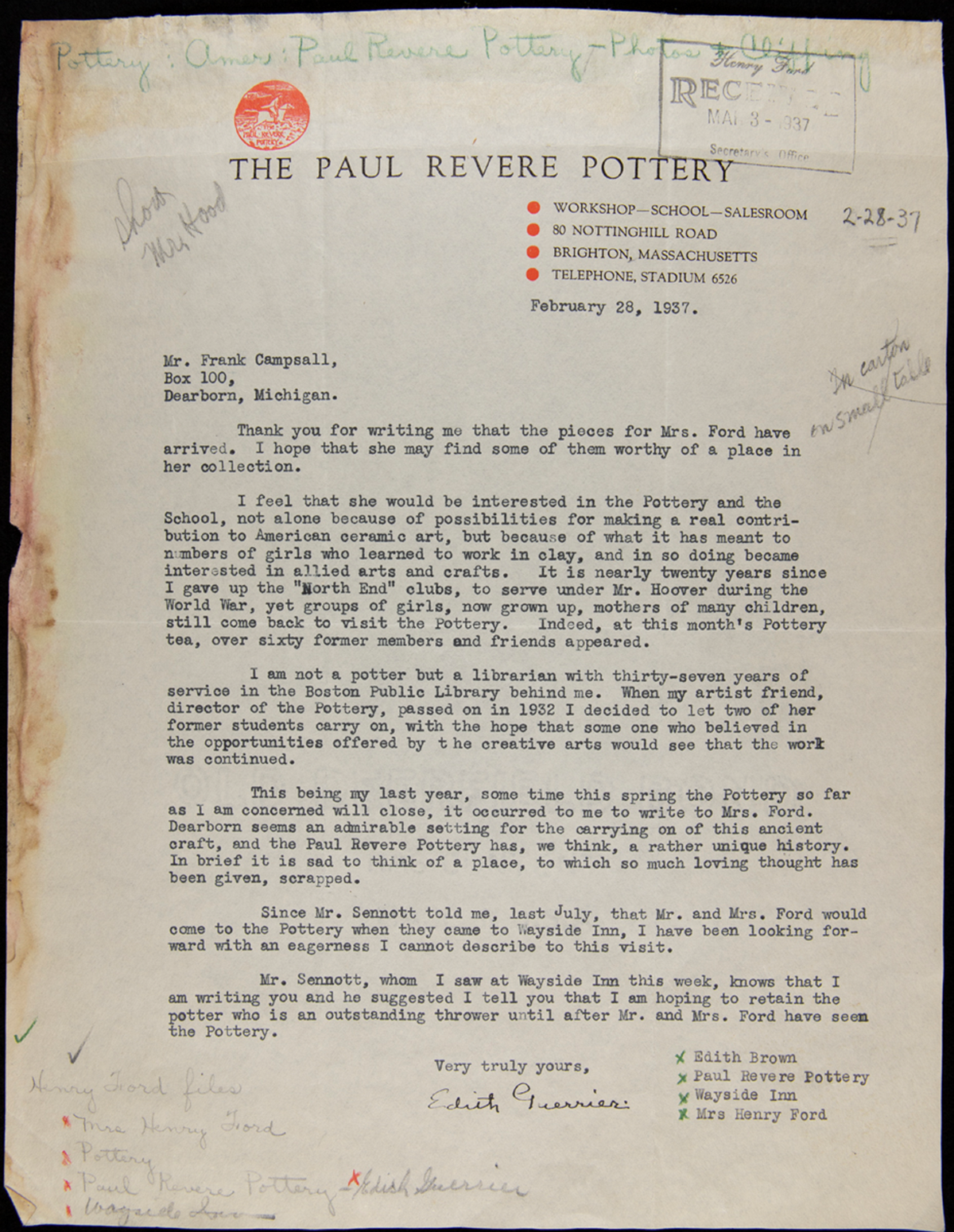

Letter from Edith Guerrier to Frank Campsall, private secretary to Henry and Clara Ford, February 28, 1937 / THF278757

Clara Ford wrote back through her private secretary, Frank Campsall, and R.J. Sennott, the superintendent of the Wayside Inn, who surveyed the pottery and concluded that the equipment was “worn, but usable.” The correspondence between the Fords and Guerrier continued until 1942, when Guerrier tried one last time to attract the Fords. Reading between the lines, it appears that while Clara appeared interested, Greenfield Village already had an operating pottery shop, so there was no need to acquire another.

Shortly after the last letter in 1942, Guerrier closed the pottery. Of course, we need to remember that it was in the middle of the Second World War, with an uncertain future. And, as Guerrier stated in her letter, she wished to see the pottery continue, but she also wished to retire. The S.E.G. reunions continued for another two decades, as did the S.E.G. News.

Guerrier wrote her autobiography in the 1950s, but it wasn’t published until 1992. Today, this story is recognized as a remarkable chapter in American social and cultural history. It is ultimately a story of the empowerment of women by women.

Charles Sable is curator of decorative arts at The Henry Ford. This article was created with the assistance of Aimee Burpee, associate registrar for special projects.