Posts Tagged 20th century

1967 Ford Mark IV Sports Car Racing: An American Way of Doing Things

The Mark IV gave Ford the second of four consecutive Le Mans victories, starting in 1966. Ferrari had dominated the 24 Hours of Le Mans, winning 8 of 12 races from 1954 through 1965. THF90733

The film Ford v. Ferrari, staring Matt Damon and Christian Bale, reignited interest in Ford Motor Company’s racing efforts at Le Mans in the 1960s. While the movie focuses on Ford’s 1966 victory, the automaker returned to Le Mans in 1967 with the Mark IV.

This was the first all-American car and team to win the Le Mans 24-hour race. For decades, Europeans had dominated sports-car racing in cars with small, fast-turning, highly efficient engines. Americans typically used big, slower-turning, less-efficient V-8 engines. This car’s sophisticated chassis used aerospace techniques, and its shape was refined in a wind tunnel. But its big engine was based on Ford’s V-8 used for stock-car racing.

Close-up View of the Ford Mark IV Le Mans Engine, June 1967. THF119457

The second-place Ferrari was more complicated and temperamental than the first-place Ford. It had a V-12 engine with fuel injection and twin distributors. The Ford (pictured above) had a V-8 engine with two four-barrel carburetors.

Dan Gurney and A. J. Foyt Popping Cork of Victory Champagne at the 24 Heures du Mans (24 Hours of Le Mans) Race, June 1967. THF127985

Two of America’s great race drivers, A.J. Foyt, right, and Dan Gurney, teamed up to win the 1967 24 Hours of Le Mans in this car. Gurney’s post-race celebration included racing’s first-ever champagne spray.

Close-up View of the Ford Mark IV Le Mans Race Car Hull Honeycomb Construction, 1967 / detail. THF87021

Holes cut in the chassis show its aircraft-style construction of aluminum honeycomb. The concept was to make it strong and lightweight.

Want to learn even more? See the Mark IV for yourself in Driving America inside Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Mark IV, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, Ford Motor Company, race cars, 20th century, 1960s, Europe, Le Mans, racing, cars

Sesame Street 50th Anniversary

Big and Little Bird reinforce the concept of contrasting sizes in this 1973 Playskool puzzle. THF97463

No television show has influenced how we think about children’s learning and thought processes as much as Sesame Street. For 50 years, this innovative TV show has continually broken barriers in its portrayal of diverse human interactions and relationships, its clever integration of Jim Henson’s wildly creative Muppets, and its rapid-fire approach to teaching basic educational concepts.

The idea for Sesame Street began back in 1966 at a dinner party hosted by Joan Ganz Cooney, a TV publicist turned documentary producer, and her husband Tim. In attendance was Lloyd Morrisett, who was both Vice President of the philanthropic Carnegie Corporation and an experimental psychologist interested in children’s education. At the dinner, Morrisett described his three-year-old daughter’s fascination with television—which included not only tuning in to Saturday morning cartoons, but also watching the pre-programming test patterns on the screen and reciting every commercial jingle by heart. Talk turned to the potential of television as a medium for educating young children. Could the seemingly addictive quality of TV be harnessed to both entertain and instruct?

This monster with the insatiable appetite—especially for cookies—has, under adult pressure, increasingly shown an awareness for healthy eating habits. THF97460

Cooney quickly developed a proposal entitled, “The Potential Use of Television in Preschool Education.” Her goal was groundbreaking at the time—to test the premise that TV could help level the playing field in education, preparing less advantaged three- to five-year-olds for school by teaching basic academic skills, self-esteem, and positive socialization. In March 1968, Cooney and Morrisett announced the formation of the Children’s Television Workshop (CTW) and set out to create an educational TV show that would both appeal to young children and help them get a jump on learning. With an eight-million-dollar startup grant from private foundations and government agencies (including the rather skeptical Department of Education), Cooney was able to test ideas for the type of show she had in mind.

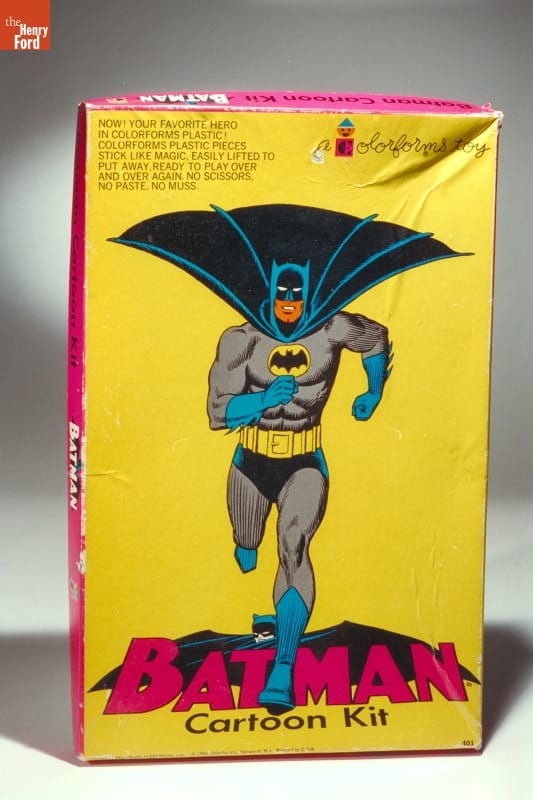

The colorful, fast-paced Batman TV show, which premiered in January 1966, provided one of many inspirations for Joan Ganz Cooney in creating Sesame Street. THF6651

Cooney’s reference points included the rapid-fire pacing of the hip new adult-oriented TV show, Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In. The campy breakout TV show Batman also provided a model, with its fast-paced action as well as its bright, bold colors and even its use of cartoon balloons. Cooney drew additional inspiration from short TV commercials, with their simple melodies in bright major keys. She did not get inspiration from most children’s TV shows, which she thought were dull, slow-paced, and seemed more oriented to adults than kids—with the possible exception of the kid-friendly Captain Kangaroo.

This 1970s Fisher-Price music box plays the song, “The People in Your Neighborhood,” while the Sesame Street scene moves horizontally across the “TV screen.” THF135804

Cooney soon realized that, while she had plenty of vision, she needed help in writing, directing, and producing the show. For this, she called on several veterans from Captain Kangaroo—most significantly Jon Stone, who played such a significant leadership role in shaping Sesame Street that he took over as executive producer for the next 20-odd years. Other talented and dedicated scriptwriters, composers, and directors also joined the team, while psychologists and educators lent their support from the beginning.

Cooney and her collaborators initially created a show that included brief skits, musical numbers, cartoons, and live-action video footage—all basically teaching school-readiness concepts. The idea of portraying a diverse group of people living and working together in a community was intentional, providing a hopeful real-life model for an integrated society, which encouraged respect, mutual tolerance, and cross-cultural friendship. The live action scenes were interspersed with pre-taped “commercials”—that is, short “bits” about letters and numbers presented either as animated segments or featuring Jim Henson’s Muppets. The live-action segments were purposely kept separate from the pre-taped “commercials,” as researchers felt that combining these “reality” and “fantasy” elements would confuse children.

Having the sweetly quizzical Big Bird live in a nest near, and interact with, the live actors on Sesame Street became a key to the show’s success. THF97451

Initial testing, however, revealed that children thought the live-action scenes were boring, the dialog tedious and lengthy. On the other hand, they found the short “commercials” to be catchy and memorable. Pushing back on the researchers’ advice, Cooney and Stone brought in Jim Henson as a full-time producer, while his Muppet creations Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch joined the live-action human cast. The resulting interaction between humans and Muppets—seamless and convincing—provided the missing alchemy. The foundation was laid for Sesame Street as we know it today.

Ongoing episodes about ultra-serious Bert and fun-loving Ernie reinforce to children that vastly different personalities can still be good friends. THF92308

The first episode of Sesame Street premiered on November 10, 1969 and the show aired weekdays on the new Public Broadcasting System (PBS) network. It was immediately hailed as a groundbreaking blend of learning and fun, despite some criticism about its high entertainment quotient, its threat to teachers for undermining early school lessons, and—in Mississippi—its initial banning because of its integrated cast. Time magazine featured popular Sesame Street character Big Bird on its November 23, 1970 cover, next to the headline, “Sesame Street: TV’s Gift to Children.” This issue devoted nine pages to the show’s impact and importance, calling it “the best children’s show in TV history.”

Puppeteer Kevin Clash breathed new energy and vitality into Elmo in the 1980s, but this furry red Muppet became a breakout star in 1996, when comedienne Rosie O’Donnell featured both Clash and this doll on her TV show. THF176791

As Sesame Street has continually changed and grown with the times, its popularity and impact have endured. Comedienne Rosie O’Donnell, whose remarks on her own TV show helped transform Elmo from a minor character to a superstar, described the show’s unique contributions this way:

"From the beginning Sesame Street encouraged imagination and playfulness. It always felt like a show to me about freedom, and it has always spoken to children in a pure and truthful way. Children are children, rich or poor, and there is a language of truth that is innate to these tiny, undeveloped beings that they can hear. Sesame Street had respect for its audience and respect for itself. They never cut any corners and they stuck to their democratic ideals."

Innovative, groundbreaking, and radical when it was introduced, Sesame Street has become nothing short of an American institution.

Donna Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

1960s, 20th century, 21st century, 2010s, TV, popular culture, Jim Henson, education, childhood, by Donna R. Braden

History of the J.R. Jones General Store

J.R. Jones General Store in Greenfield Village, 2001 (THF138628)

The Waterford Country Store—as it was initially called in Greenfield Village—was the first building to arrive in the Village. Re-erected on the Village Green in 1927-28, it was soon joined by other buildings—a schoolhouse, courthouse, tavern, town hall, and chapel—that to Henry Ford all symbolized America’s spirit of community. New research in the 1990s revealed that, between the time the store was built in 1856-57 and the time Henry Ford brought it to Greenfield Village in the 1920s, nine different storekeepers had operated a general store out of this building. A reinstallation of the building in the 1990s refocused the store’s furnishings and interpretation on the era of 1882 to 1888—when J.R. Jones ran the store in Waterford, Michigan.

Store Interior, 1925 (THF69132)

This is an interior view of the stocked, fully functional store in 1925, when the August Jacober family operated it in Waterford, Michigan. The Jacobers were the last family of proprietors to run this store before it was brought to Greenfield Village.

Store exterior, 1926 (THF126117)

This photograph depicts the general store in Waterford, Michigan, just before it was removed to Greenfield Village in 1926. According to Jacober family descendants, this store was raised on skids in the street because the family was building a new brick store on its original site. Ford likely saw the old store, had his agents arrange to purchase it around August 1927, and then had it moved to Greenfield Village.

Store exterior in Greenfield Village, 1958 (THF138605)

When Henry Ford first envisioned a Village Green as the centerpiece of his recreated village in Dearborn, the general store was situated and reconstructed on what would become its permanent location. The Elias Brown sign that hangs out front in this 1958 image came from upstate New York. During this time, the store was known as the Elias Brown General Store.

Store interior in Greenfield Village, 1965 (THF126771)

To furnish the building with authentic general store artifacts from the past, Ford sent agents in search of unsold stock that might still remain in old general stores. Their finds primarily came from stores in upstate New York and New Hampshire. By the 1960s, as seen in this image, the interior was furnished not only with old store stock but also with penny candy that visitors could purchase.

Store exterior, 1994, with vintage Lah-de-Dahs baseball team posing in front (THF136301)

Research in the 1990s led to a new, more accurate historical interpretation of this store as it existed in Waterford, Michigan, during the 1880s. This era was chosen to represent a transition in stores—from old-fashioned displays of pickle barrels and flour bins to shelves stocked with more modern products like canned goods and brand-name items. A new sign with the name of the proprietor of this store in Waterford during the 1880s—J.R. Jones—replaced the old Elias Brown sign over the front entrance.

Store interior, 2008, with historically-dressed presenter (THF53771)

Use of period photographs, account books, and inventories led to the choices of stock for the store. Presenters in this building—dressed in accurately-researched historic clothing—tell the stories of J.R. Jones, the customers who shopped here in the 1880s, and the products they might have purchased.

Donna Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

shopping, 20th century, 19th century, Michigan, J.R. Jones General Store, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, entrepreneurship, by Donna R. Braden, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Thomas Edison Goes Hollywood

A scene from the 1940 motion picture, “Young Tom Edison,” starring Mickey Rooney. THF125222

Spencer Tracy portrayed the inventor in the film, “Edison the Man,” released later that same year. THF58062

Thomas Alva Edison is an American “superhero.” It is not surprising, then, that his life story found its way into the movies during Hollywood’s golden age. It is, in fact, quite fitting, since Edison and an associate were instrumental in the development of early movie technology in the 1890s.

In 1940, Edison was the subject of not one, but two, Hollywood films: “Young Tom Edison,” starring Mickey Rooney, and “Edison the Man,” starring Spencer Tracy. These classic motion pictures were filmed in California. But Henry Ford’s well-known collection of Edison-related buildings and artifacts in Dearborn played a supporting role in MGM’s research for script development and set design.

To help prepare for their roles, MGM wanted the actors playing Thomas Edison to visit the Museum and Village to learn more about Edison. Here, Mickey Rooney records his voice on an early Edison tinfoil phonograph. THF125217

In February 1939, MGM scriptwriters Dore Schary and Hugo Butler came to Greenfield Village to see the Menlo Park Laboratory and the Edison-related artifacts in the Museum. (Schary and Butler later received an Academy Award nomination for their script for “Edison the Man.”) MGM also wanted the actors playing Thomas Edison in the films to be inspired by their own visits to Dearborn. Rooney arrived on October 23, 1939, just before filming of “Young Tom Edison” began in Hollywood. Tracy came a few days later.

A few weeks after his visit, Spencer Tracy wrote this letter of appreciation to Henry Ford. THF125214

Tracy was deeply impressed by his visit and wrote a letter to Henry Ford, “I am unable to find words to adequately express the deep and lasting imprint my short visit has made upon me…I shall make a supreme effort to do some small justice and no harm to the memory of your dear friend.”

Henry Ford lent an 1850s locomotive and some railroad cars from his museum for the publicity train that carried special guests from Detroit to Port Huron for the February 1940 premiere of “Young Tom Edison.” THF96236, THF96230

As the train rolled along from Detroit to Port Huron, Mickey Rooney hawked candy and newspapers to the passengers, just as Edison had done as a boy years before. Here, Rooney offers Edison’s widow, Mina Miller Edison Hughes, a newspaper. THF119959

As the special train arrived in Port Huron, fans rushed to greet Mickey Rooney. THF119966

Souvenir from “Young Tom Edison” February 1940 movie premiere. THF96232

Filming began on “Young Tom Edison” in early November 1939. By Christmas, it was complete, and MGM was planning for the film’s February 10, 1940, premiere in Port Huron, Michigan, where Edison had grown up. The festivities included a train ride from Detroit to Port Huron--the same route traveled by Edison in his youth when he sold candy and newspapers on the Grand Trunk railroad. Artifacts from the Museum added authenticity. Henry Ford loaned the 1858 “Sam Hill” steam locomotive and some train cars for the trip. Among the passengers were the film’s star, Mickey Rooney; Edsel Ford; Thomas Edison’s widow, Mina Miller Edison Hughes; and MGM studio executive Louis B. Mayer. In evening, “Young Tom Edison” premiered at three Port Huron theaters, with Rooney appearing at each.

Henry Ford shows Spencer Tracy around the Menlo Park Lab in Greenfield Village during Tracy’s October 1939 visit. THF123498

With the help of photographs and other documentation provided by Greenfield Village staff, MGM built an impressive full-sized version of the Menlo Park laboratory in California for “Edison the Man.” The movie set looked astonishingly like its Greenfield Village counterpart! THF125210

In mid-January 1940, filming began on “Edison the Man.” With the help of photographs and other documentation provided by Greenfield Village staff, MGM built an impressive full-sized version of the Menlo Park Laboratory, with its equipment, furnishings, and rows of bottles on the shelves. The movie set looked astonishingly like its Greenfield Village counterpart.

During the filming, Henry Ford put William Simonds on loan to MGM as a technical assistant. Simonds, a public relations manager for the Village and Museum, had published an Edison biography five years before. During the two-month filming of “Edison the Man” at MGM, Simonds reported back regularly. His letters provide an engaging behind-the-scenes look at the making of this classic Hollywood film.

Simonds told how Rita Johnson’s nervousness at playing her first big role--as Edison’s wife Mary--forced extra takes to complete some scenes. In one instance, Tracy ate five pieces of apple pie during numerous retakes of a scene. Simonds humorously described director Clarence Brown facing a long line of mothers and crying babies to choose an infant to play Edison’s child. He revealed how the stage crew had to scramble to repair the damage when part of the Menlo Park Laboratory set fell over, breaking many of the “chemical” bottles and spilling colored water all over the floor.

The model was sent to Henry Ford as a keepsake. Art director Cedric Gibbons, director Clarence Brown, cinematographer Harold Rosson, and the film’s stars Spencer Tracy and Rita Johnson signed it. THF49762

Filming of “Edison the Man” wrapped up in mid-March 1940 and it premiered May 16, 1940. There had been talk of holding its premiere in Dearborn, but, at the request of Edison’s son Charles, the film premiered in West Orange, New Jersey, where Edison developed many of his later inventions.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Thomas Edison’s Menlo Park Laboratory

- Sarah Jordan Boarding House

- Thomas Edison, Innovator and Beachcomber

- Menlo Park Library

California, Michigan, 1940s, 1930s, 20th century, Thomas Edison, popular culture, movies, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, by Jeanine Head Miller, actors and acting

Man Who Sold First Mustang Reunited with Car 55 Years Later

1965 Ford Mustang Convertible, Serial Number One. THF90618

1965 Ford Mustang Convertible, Serial Number One. THF90618

Ford Mustang Serial Number 1 and Original Owner Captain Stanley Tucker, 1966. THF98053

More than 55 years ago, Harry Phillips sold Mustang Serial No. 1 to Stanley Tucker in St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada.

The very first Mustang sold was a pre-production model only intended for display. It was meant to be sent back to Ford, and it took nearly two years for the car to be officially returned.

Harry Phillips and Mustang Serial No. 1, September 2019.

Thanks to a campaign spurred on by fellow Ford Mustang lovers, Mr. Phillips was reunited with that same car, in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, on Sept. 27, 2019. Hear his story of that landmark sale in 1964, and learn more about this important artifact: Stanley Tucker and Ford Mustang Serial Number One.

Continue Reading

Canada, Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, 20th century, 1960s, Mustangs, Henry Ford Museum, Ford Motor Company, events, convertibles, cars

What We Wore: Kids!

As we continue to celebrate our first year of What We Wore--our new collections platform in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation--a new group of garments from The Henry Ford’s rich collection of clothing and accessories makes its debut.

This season it’s all about kids.

Sailor Suit, about 1925

Sailor suits were popular from the 1870s into the 1930s—with short or long pants for boys and skirts for girls. These nautically-themed outfits were usually made of sturdy washable fabrics and, though stylish, allowed kids a bit more freedom of movement.

Jumper and Blouse, 1958–1960 (Gift of Mary Sherman)

In the 1950s, girls still wore dresses or skirts much of the time—for formal occasions and for school. Pants were play clothes—what girls wore after school to run around the yard or play indoors.

"Wrecker" Coordinating Shirt and Pants, 1978 (Gift of Diana and John Mio)

Designs with kid appeal often appear on children’s casual clothing— images like cars and trucks, princesses, dinosaurs, animals, butterflies, and monsters.

Blouse and Pant Outfit, about 1935

This girl’s casual outfit was inspired by adult fashion—beach pajamas, informal resort wear sporting wide pantlegs. Cheerful, pastel prints were popular during the Depression era.

Leisure Suit, 1977 (Gift of Diana and John Mio)

The casual and versatile leisure suit reached the height of popularity with adult men in 1977, when John Travolta wore a white version to the disco in the movie Saturday Night Fever. Even kids donned this ultimate—and short-lived—1970s fashion trend.

Dress, about 1920 (Gift in Memory of Augusta Denton Roddis)

In the 1920s, simple dresses were preferred for younger girls. Linen fabric and pale colors were popular for summer wear. The understated details on this dress are embroidered, crocheted and tatted—the children’s mother was a skilled needlewoman.

The Building Blocks of Childhood

Children love to build things--whether they create imaginary worlds or smaller versions of the real one. Construction toys are quite literally and figuratively “the building blocks of childhood.” Playing with them builds physical and intellectual skills--and encourages creativity. Toy bricks, logs, and girders are the stuff of playtime joy!

Entrepreneurs have introduced innovative construction toys that have delighted new generations of children. Which is your favorite? For the LEGO fans, Towers of Tomorrow with LEGO® Bricks, a first-of-its-kind, limited-engagement exhibition, is rising up in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation October 12 through January 5, 2020.

Junior Tinkertoy for Beginners Set, 1937-1946

American Plastic Bricks, about 1955 (Gift of Miriam R. Epstein)

Lincoln Logs, about 1960 (Gift of Steven K. Hamp)

Dream Builders Super Blocks Building Set, 1991-1992

20th century, What We Wore, toys and games, Henry Ford Museum, fashion, childhood, by Jeanine Head Miller

Hooked on Comic Books

Astonishing Tales, vol. 1 no. 29, 1975, featuring Guardians of the Galaxy - a reprint of their first appearance (1969) in Marvel Super-Heroes vol. 1 no. 18. THF305338

It started the summer I turned 14, when some neighbor kids told us they were moving and wanted to find a good home for their sizable stash of D.C. comic books. My four brothers and I had a hard time turning that down! The next thing we knew, several boxes of comic books arrived on our doorstep—opening a magical door into a world previously unknown to me.

Archie, vol. 1 no. 102, July 1959. THF100874

Up until that time, I’d only read younger kids’ comic books—like Archie, Richie Rich, and Little Lotta. But these were different, these D.C. comics that recounted the exploits of such larger-than-life superheroes as Superman, The Flash, and my personal favorites—the teenage Legion of Super-Heroes.

Adventure Comics, featuring Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes, vol. 1 no. 343, April 1966. THF 305335

My Mom was rather horrified when she learned of our new “acquisition.” She pictured us wasting our summer away reading these comic books rather than doing things that were—as she called it—more “constructive.” I must admit that I did spend many hours that summer immersed in the pages of those comic books. But in no way would I call it wasting my time. Through those comic books, I learned about how stories can be told through a series of pictures, how pictures can illuminate ideas and feelings, and how all of this can fuel a young reader’s imagination.

First issue of Spider-Man I purchased, vol. 1 no. 88, September 1970 (author’s collection).

One evening a few years later, my comic book world shifted. My best friend introduced me to the backstory of Spider-Man—a completely different kind of comic book superhero created by Marvel, a completely different kind of comic book company. Spider-Man had problems. And flaws. And continual feelings of self-doubt. Here was a superhero who was reluctant, questioning, always feeling like a failure even when he just happened to save the world. On top of that, he was a teenager—just like me! Who couldn’t relate to that? I was forever done with Superman. So long, D.C.! Hello, Marvel!

Spider-Man, vol. 1 no. 96, May 1971 – an unprecedented issue at the time. It did not display the Comics Code Authority stamp of approval like virtually all comic books at the time because it involved a drug-related story (author’s collection).

I soon branched out to other Marvel comic books. I became especially enamored with the stories of Dr. Strange, whose mystical world fascinated me and whose page after page of colorful psychedelic graphics captivated me even without the stories. I also went through a Silver Surfer period, appreciating his feeling of alienation from all human beings who inhabited Planet Earth. I tried many additional titles, but Spider-Man remained my perennial favorite.

Dr. Strange, vol. 1 no. 171, August 1968, displaying typically striking graphics on the cover (author’s collection).

As I entered college, my passion for comic books came along with me. I rode my new 10-speed bicycle down miles of back roads to visit used comic book stores and attend the occasional comic book show. I joined a comic book enthusiasts’ group with fellow students, where we traded likes, dislikes, and back issues. I made inventories, kept needs lists, bought enthusiasts’ magazines, and traced the lineage of my favorite titles by searching for back issues. This was all in the days before the Internet, eBay, and Comic Cons, and most communication was accomplished through the mail.

Silver Surfer, vol. 1 no. 1, August 1968 (author’s collection).

When I began my job as a curator here at The Henry Ford in 1977, my interest in comic books finally waned. Maybe I didn’t need that brand of escapism or that kind of outlet for my imagination anymore. Maybe I was too busy to take the time to delve into the stories. Comic books themselves changed. I remember feeling frustrated by Marvel’s trend, during the late 1970s, with story cross-overs throughout the entire network of their comic book titles to encourage more comic-book buying. Who had the patience and perseverance for that? Or the money, as the price of comic books soared at that time, from 15 cents in the late 1960s to 40 cents by 1980? This is also about the time that Spider-Man went mainstream, with a newspaper comic strip (starting 1977) and a Saturday morning cartoon (premiering 1981), both aimed at kids much younger than me. It seemed weird that, suddenly, I shared a common bond with my little five-year-old nephew—although he acted suitably impressed when I pulled out some of my old Spider-Man comic books for him, which by then seemed like ancient relics.

I might have let go of my comic book passion for good, but some project at the museum would always pull me back. For example, during my writing of the museum book Leisure and Entertainment in America (1988), I acquired a group of early comic books for the museum’s collection.

Tales from the Crypt, vol. 1 no. 43, September 1954 - an early 1950s horror comic book title whose shocking content alarmed parents and helped lead to the comic book industry’s self-censorship board, called the Comics Code Authority. THF141540

When we decided to include a section on how people imagined the future in the Your Place in Time: 20th Century America exhibit, I acquired a range of comic book titles that focused upon futuristic themes.

Spider-Man 2099, vol. 1 no. 1, November 1992 – a futuristic re-imagining of the original character (note steep $1.75 price by this time). THF305334

To my delight, the topic of comic books will be included in the upcoming filming for The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation. And next summer, the Marvel: Universe of Super Heroes traveling exhibit is headed our way in 2020. Here I am, more than a half-century later—and still hooked on comic books!

Back when I was a kid, many parents (including my own) worried about the harmful effects that reading comic books had on youth. In retrospect, I’d have to say that they were completely wrong. For me, comic books expanded my world immeasurably. They encouraged me to read, to write, to draw, to tap into my imagination. Maybe this started with those early Archie comic books. It certainly grew when that stash of D.C. comics landed on our front doorstep. But it blossomed and permanently formed who I am today when I entered the Marvel Universe.

Happy 80th birthday, Marvel!

Donna Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

20th century, popular culture, comic books, by Donna R. Braden

“Batman Cartoon Kit” Colorforms, 1966-68. THF 6651

It was the 1960s—the golden age of television. Some 95% of American homes boasted at least one TV. These were primarily black and white sets, as color TV was still out of the reach of many families. It’s hard to imagine now but there were only three channels at the time. Every year, the three networks (CBS, NBC, and ABC) vied for viewer ratings, shifting and changing shows and showtimes at two pivotal times during the television season—Fall and Winter.

As the Fall 1966 season unfolded, it became evident to TV viewers that something extraordinary was happening. Sure, there were the usual long-running sitcoms, like Green Acres, Petticoat Junction, and The Beverly Hillbillies. But change was in the wind. A new crop of programs emerged—colorful, fast-paced, poking fun at things that were supposed to be serious and exploring contemporary social issues.

Why the difference all of a sudden? Many of these shows were aimed at the youth audience, considered by this time an influential group of TV watchers. Others purposefully took advantage of the new color televisions. Sometimes show producers and creators were simply tired of the old formulas and wanted to break out of the box.

Let’s take a look at a few highlights from the 1966-67 TV season—starting with the staid and true and working up to the wild and wacky—and see what all the hubbub was about!

Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color (Sunday, 7:30-8:30 p.m., NBC)

Snow Globe, “The Wonderful World of Disney,” 1969-79. THF174650

On Sunday nights since 1954, millions of Americans had tuned in to watch Walt Disney host his TV show, with a changing array of animated and live-action features, nature specials, movie reruns, travelogues, programs about science and outer space, and—best of all—updates on Walt Disney’s theme park, Disneyland. Since 1961, this show had been broadcast in color.

The 1966-67 season was particularly memorable because Walt Disney tragically passed away on December 15, 1966. But since the episodes had been pre-recorded, there was Walt still hosting them until April 1967. Viewers found this both comforting and disconcerting. Finally, after April, Walt was dropped as the host and, eventually, the show was retitled The Wonderful World of Disney. It ran with solid ratings until the mid-1970s.

Bonanza (Sunday, 9:00-10:00 p.m., NBC)

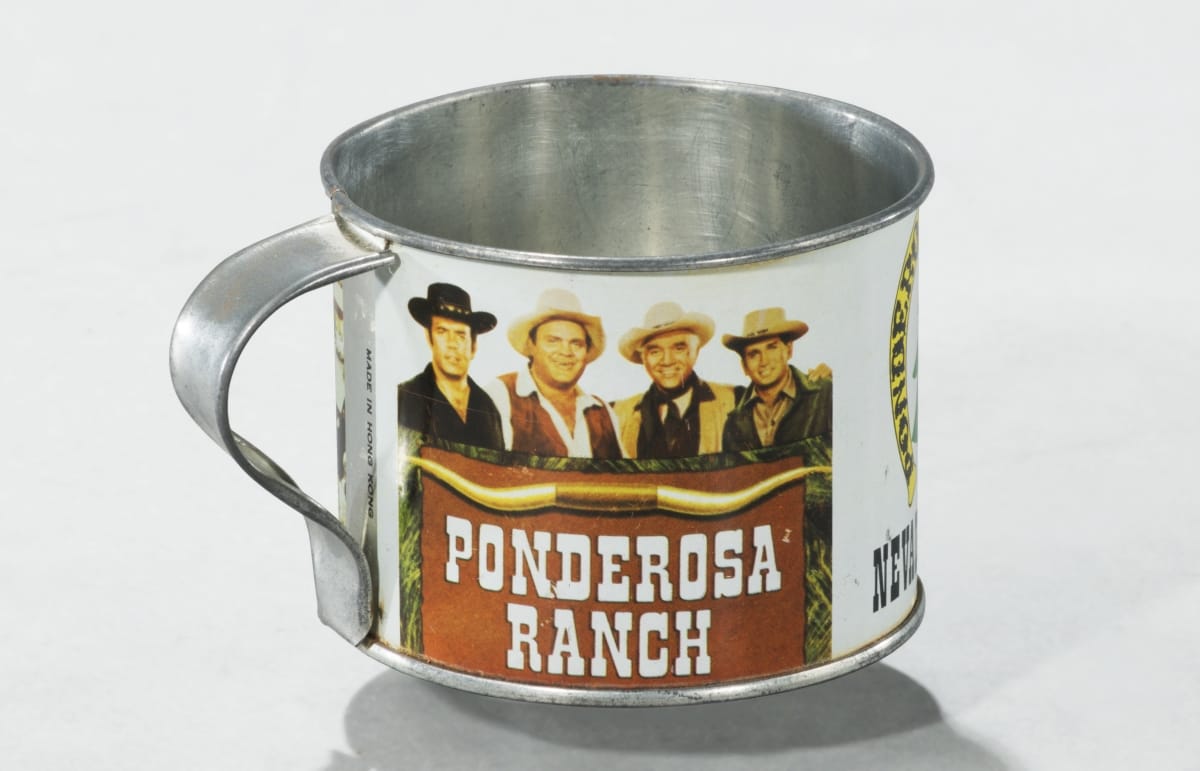

“Ponderosa Ranch” Mug, ca. 1970. THF174648

Viewership was high on NBC on Sunday nights at 9:00, as Bonanza was one of the most popular TV shows of all time. Running for 14 seasons and 430 episodes, this series about the trials and tribulations of widower Ben Cartwright and his three sons on the Ponderosa Ranch was an immediate breakout hit when it premiered in 1959, amidst a plethora of more run-of-the-mill prime-time westerns. Its popularity was primarily due to its quirky characters and unconventional stories—including early attempts to confront social issues. It was the first major western to be filmed in color and was the top-rated show on TV from 1964 to 1968. Bonanza ran until 1973.

The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (Friday, 8:30-9:30, NBC)

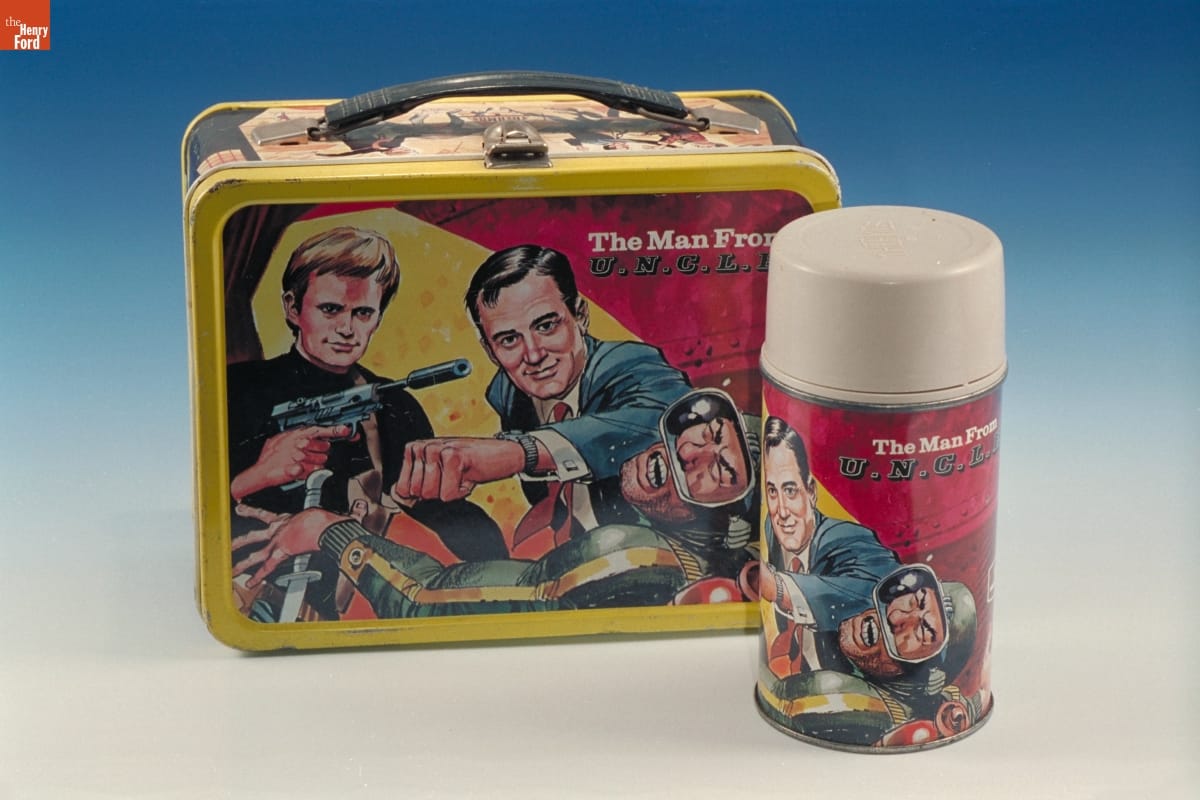

“The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” lunchbox and thermos, 1966. THF92303

Premiering in September 1964, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. took full advantage of the popularity of the spy genre launched by the James Bond film series. In fact, early concepts for it were conceptualized by Bond creator Ian Fleming. In this series, Napoleon Solo (originally conceived as the lone star) and Russian agent Ilya Kuryakin (added in response to popular demand) teamed up as part of a secret international counterespionage and law enforcement agency called U.N.C.L.E. (United Network Command for Law and Enforcement). Solo and Kuryakin banded together with a global organization of other agents to fight THRUSH, an international organization that aimed to conquer the world.

During this, the Cold War era, it was groundbreaking for a show to portray a United States-Soviet Union pair of secret agents, as these two countries were ideologically at odds most of the time. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was also known for its high-profile guest stars and—taking a cue from the Bond films—its clever gadgets. In 1966, this series won the Golden Globe for Best Television Program and, building upon its popularity, spun off into two related double-feature movies that year. Unfortunately, attempting to compete with lighter, campier programs of the era, the producers made a conscious effort to increase the level of humor—leading to a severe ratings drop. Although the serious plot lines were soon reinstated, the ratings never recovered. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was canceled in January 1968.

I Spy (Wednesday 10:00-11:00, NBC)

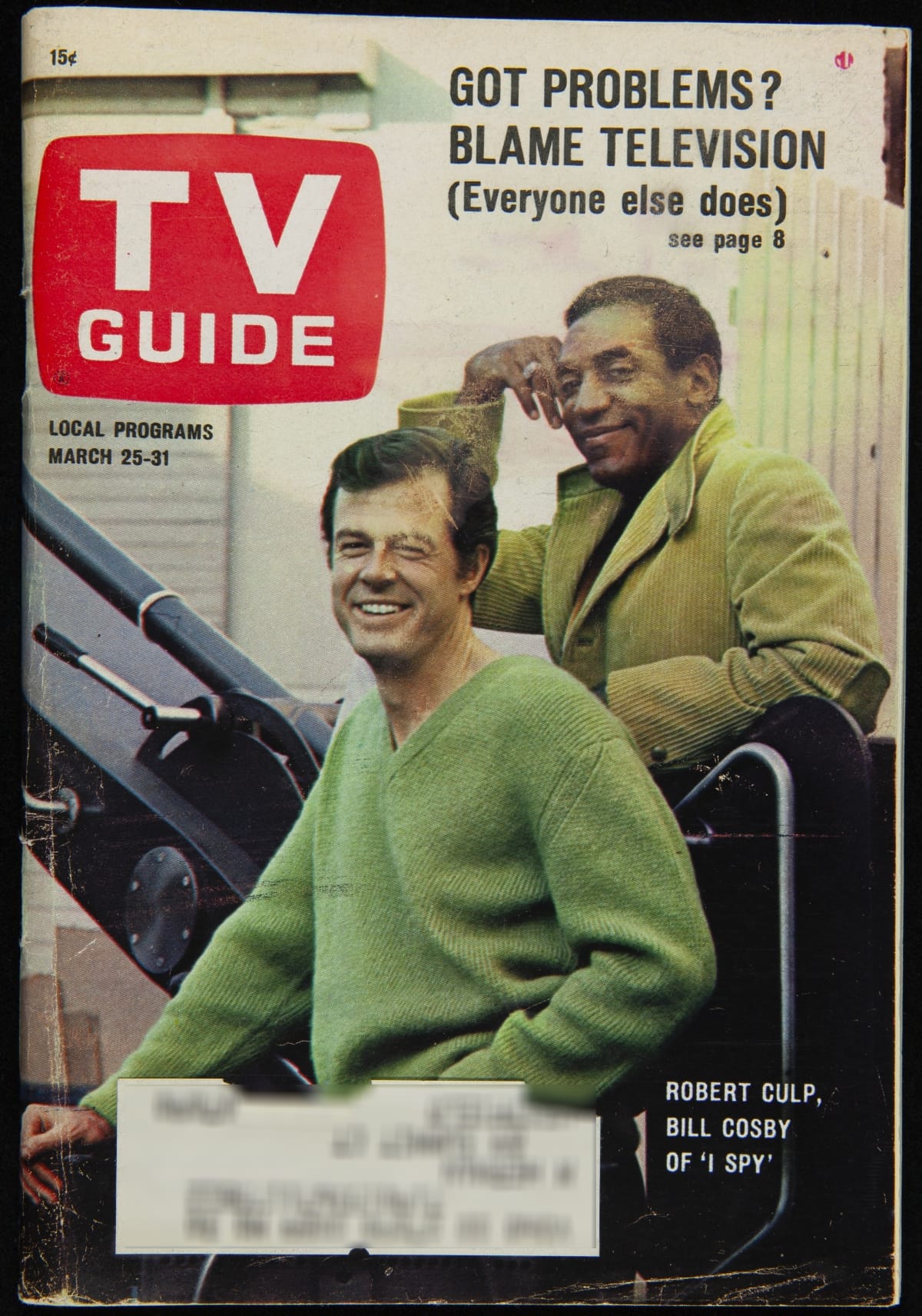

TV Guide featuring “I Spy” characters Robert Culp and Bill Cosby on cover, March 25-31, 1967. THF275655

One series that never opted for campy was I Spy, which starred Bill Cosby and Robert Culp playing two U.S. intelligence agents traveling undercover as international “tennis bums.” This series, which premiered in 1965, was also inspired by the James Bond film series and remained a fixture in the secret agent/espionage genre until cancelled in April 1968. I Spy, additionally a leader in the buddy genre, broke new ground as the first American TV drama series to feature a black actor in a lead role. It was also unusual in its use of exotic locations—much like the James Bond films—when shows like The Man from U.N.C.L.E. were completely filmed on a studio backlot.

I Spy offered hip banter between the two stars and some humor, but it focused primarily on the grittier side of the espionage business, sometimes even ending on a somber note. The success of this series was attributed to the strong chemistry between Culp and Cosby. Cosby’s presence was never called out in the way that black stars and co-stars were made a big deal of on later TV programs like Julia (1968) and Room 222 (1969).

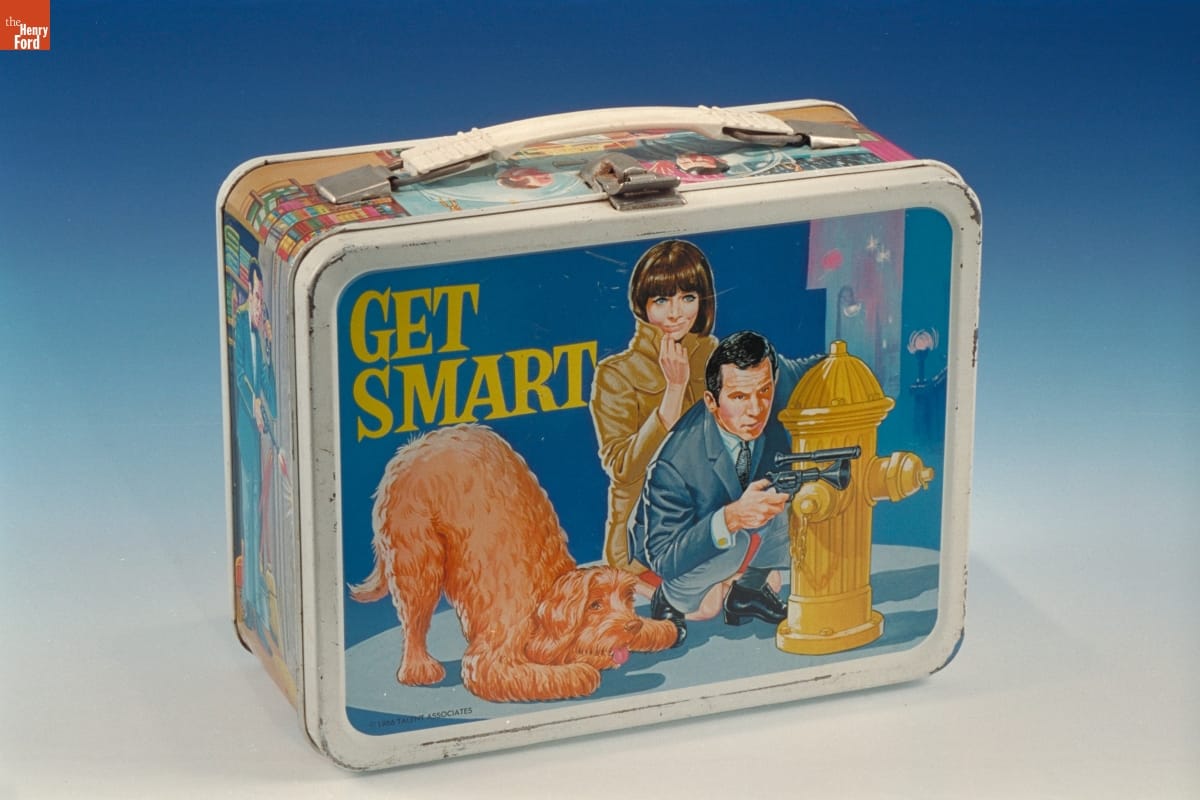

Get Smart (Saturday, 8:30-9:00 NBC)

“Get Smart” Lunchbox, 1966. THF92304

Premiering in September 1965, Get Smart was a comedy that satirized virtually everything considered serious and sacred in the James Bond films and such TV shows as I Spy and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Created by comic writers Mel Brooks and Buck Henry as a response to the grim seriousness of the Cold War spy genre, it starred bumbling Secret Agent 86—otherwise known as Maxwell “Max” Smart, along with supporting characters, female Agent 99 and the Chief. These characters worked for CONTROL, a secret U.S. government counterintelligence agency, against KAOS, “an international organization of evil.” Brooks and Henry also poked fun at this genre’s use of high-tech spy gadgets (Max’s shoe phone perhaps being the most memorable), world takeover plots, and enemy agents. Somehow, despite serious mess-ups in every episode, Maxwell Smart always emerged victorious in the end.

Get Smart was considered groundbreaking for broadening the parameters of TV sitcoms but was especially known for catchphrases like “Would you believe…” and “Sorry about that, Chief.” Despite a declining interest in the secret-agent genre, Get Smart’s talented writers attempted to keep it fresh until it was finally cancelled in May 1970.

Batman (Wednesday and Thursday, 7:30-8:00, ABC)

Toy Batmobile, 1966-69. THF174647

Bursting onto the scene in January 1966, Batman became an instant hit and took the country by storm. Batmania was in full swing by the Fall 1966-67 TV season. The series, based upon the DC comic book of the same name, featured the Caped Crusader (millionaire Bruce Wayne in his alter-ego of Batman) and the Boy Wonder (his young ward Dick Grayson in his alter-ego of Robin). These two crime-fighting heroes defended Gotham City from a variety of evil villains. It aired twice weekly, with most stories leaving viewers hanging in suspense the first night until they tuned in the second night.

This show successfully captured the youth audience, with its campy style, upbeat theme music, and tongue-in-cheek humor. Despite the fact that it verged on being a sitcom, the producers wisely left out the laugh track, reinforcing the seriousness with which the characters seemed to take the often absurd and wildly improbable situations in which they found themselves. The filming simulated a surreal comic-book quality, with characters and situations shot at high and low angles, with bright splashy colors and with sound effects, like Pow, Bam, and Zonk, appearing as words splashed across the action sequences on screen. The series was also replete with numerous gadgets and over-the-top props, with the Batmobile undoubtedly most memorable. Batman ran until March 1968, experiencing a significant ratings drop after its initial novelty faded.

Lost in Space (Wednesday 7:30-8:30, CBS)

“Lost in Space” Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967. THF92298

Loosely based upon the story of the Swiss Family Robinson, this TV series depicted the adventures of the Robinson family, a pioneering family of space colonists who struggled to survive in the depths of space in the futuristic year of 1997—as the United States was gearing up to colonize space due to overpopulation. But the family’s mission was sabotaged, forcing the crew members to crash-land on a strange planet and leaving them lost in space.

The show had premiered in September 1965 as a serious science fiction series about space exploration and a family searching to find a new place for humans to dwell. But, in January 1966, pitted against Batman’s time slot, Lost in Space producers attempted to imitate Batman’s campiness with ever-more-outrageous villains, brightly colored outfits, and over-the-top action. The plots increasingly featured Robby the Robot and the evil Dr. Zachary Smith. Viewers and actors alike strongly disapproved of this shift. The show lingered on until March 1968.

The Monkees (Monday, 7:30-8:00, NBC)

“Monkees” Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967. THF92313

Where other shows might have been lighthearted, campy, or tongue-in-cheek, The Monkees at times verged on pure anarchy. This series, which premiered on September 12, 1966, led off NBC’s prime-time programming every Monday night. It lasted only two seasons but during that time, its star shone brightly. The Monkees followed the experiences of four young men trying to make a name for themselves as a rock ‘n’ roll band, often finding themselves in strange, even bizarre, circumstances while searching for their big break. Aimed directly at the youth audience, the band members were characterized as heroes down on their luck while the adults were consistently depicted as the “heavies.”

The Beatles’ films A Hard Day’s Night and Help! inspired producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider to create not only a show about a rock ‘n’ roll band but also to adapt a loose narrative structure (each member of the Monkees was trained in improvisational acting techniques at the outset of the show) and the musical sequences or “romps” that appeared each week. The series built a reputation for its innovative use of avant-garde filming techniques like quick jump cuts and breaking the fourth wall (that is, having the characters directly address the TV viewers). A well-oiled marketing machine behind the show also ensured that strong tie-ins were maintained with teen magazines, merchandise, and live concerts.

The Monkees won the Emmy for best comedy series during its first, the 1966-67, season. However, backlash was inevitable among critics and older teenagers when the Monkees admitted that they did not play their own instruments—although they clearly played them in their live concerts and, in fact, eventually had a falling-out with network executives about this very issue. Though the show was cancelled in 1968, it experienced a huge revival among younger audiences through Saturday morning reruns and especially with the 1986 MTV Monkees Marathon. Remaining band members Micky Dolenz and Mike Nesmith still attract large audiences of intergenerational fans at their live concerts, while reruns of their TV shows continue to draw new audiences.

Star Trek (Thursday, 8:30-9:30 NBC)

“Star Trek” lunchbox, 1968. THF92299

When Star Trek premiered on September 8, 1966, science fiction shows were not very advanced—or even thought of very highly. Star Trek’s closest competitor, Lost in Space, offered only shallow plots, one-dimensional characters, and fake sets. No one could imagine at the time that this rather low-key show would become one of the biggest, longest-running, and highest-grossing media franchises of all time. This series traced the interstellar adventures of Captain James T. Kirk and his crew aboard the United Federation of Planets’ starship Enterprise, on a five-year mission “to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before.”

Creator Gene Roddenberry, aiming the show at the youth audience, wanted to combine suspenseful adventure stories with morality tales reflecting contemporary life and social issues. So, to get by network scrutiny, he set the premise of the show in an imaginary future. With the freedom to experiment, he put in place one of TV’s first multiracial and multicultural casts and was able to explore through different episodes some of the most relevant political and social allegories on TV at the time. The stories were also considered exceptionally high quality for that era, involving believable characters with which viewers could both identify and sympathize. Unlike the gloomy predictions of most science fiction writings of the time, Roddenberry hoped that the futuristic utopia he created on Star Trek would give young people hope, that it would empower them to create a better future for themselves someday. Star Trek, with only modest ratings, lasted only three seasons. But it would go on to become a cult classic.

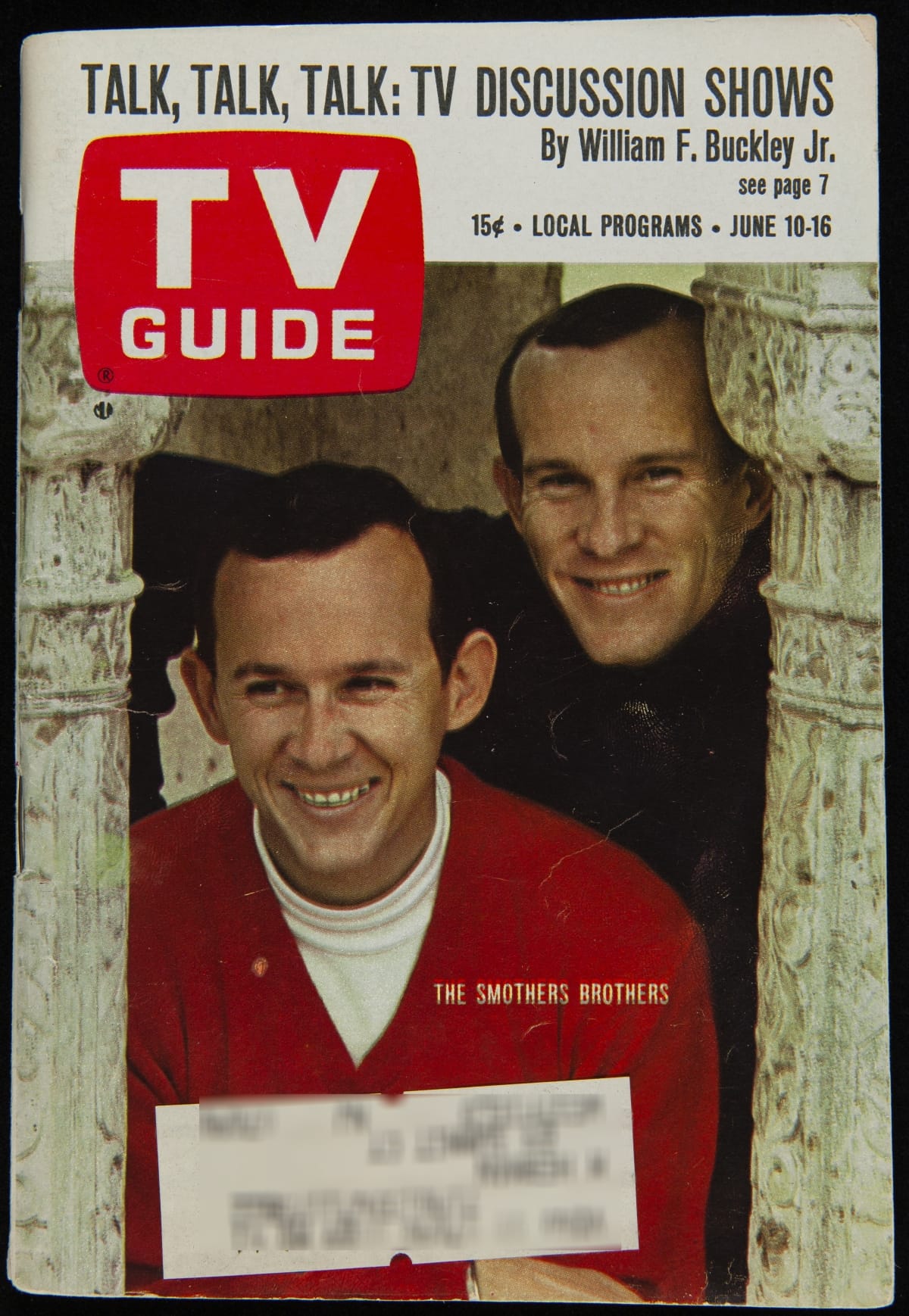

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (Sunday, 9:00-10:00 p.m. beginning February 1967, CBS)

TV Guide featuring The Smothers Brothers on cover, June 10-16, 1967. THF275657

In Fall 1966, The Garry Moore Show, a variety show on CBS hosted by the aging radio and TV star, was no match when pitted against Bonanza—even with this, its first season in color. Network executives, at their wit’s end to try to attract viewership, decided the only way they could come up with a quick replacement was to substitute another variety show. In desperation, they landed on a simple variety series featuring the soft-spoken, clean-cut, non-threatening folk-music-playing Smothers Brothers. Considered a “young act,” an added bonus was that their show might capture the coveted youth audience. Little did they know what they were in for.

As the show evolved, the brothers not only became more politicized themselves but felt that they owed it to their young viewers to increase the show’s relevance, boldly addressing overtly divisive political and social issues. Their staff of young writers was only too happy to comply. Unfortunately, as a result, the brothers were continually at odds with the network censors until the show was finally cancelled after three seasons. In its continual conflicts with network executives, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour turned the variety show genre on its ear and paved the way for Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1968) and, in pushing TV’s all-out rebellion against the status quo, led an explosive charge that resulted in 1970s shows like All in the Family (1971).

These are but a few highlights from the 1966-67 TV season. Some say that this was the greatest television season ever, a clear indication that TV had finally come of age. Because of shows like these, television would certainly never be the same again. And, come to think of it, neither would we!

Donna Braden, Curator of Public Life, was 13 years old during that memorable TV season and proudly wears her fan club button to every Monkees concert she still attends.

20th century, 1960s, TV, Star Trek, space, popular culture, music, Disney, by Donna R. Braden

Woodstock 1969

Estimate: 200,000 attendees. Over 400,000 showed up.

This flag was at Woodstock, too--a witness to this legendary event that reflected the 1960s counterculture movement’s quest for freedom and social harmony.

Flags like this one were provided to vendors, musicians, and technical crew to allow them access to the Woodstock Musical Festival grounds at Max Yasgur’s 600-acre dairy farm in upstate New York during the August 1969 event. They were to fly the flag from their vehicles or attach it to their booths.

Woodstock’s organizers--none of whom were over 27-- billed the event as “An Aquarian Exposition: Three Days of Peace and Music.” Held from Friday, August 15 and extending into the early morning of Monday, August 18, the music festival featured 32 iconic performers including Joan Baez, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Janis Joplin, The Who, the Grateful Dead and Jimi Hendrix.

An Extraordinary Event Creates Enormous Challenges

There was a lot that went right with Woodstock. And many things that didn’t. The free-spirted and peaceful audience was filled with excitement and the musicians turned in electrifying performances. But the inexperienced organizers found their planning for this unprecedented event enormously inadequate--especially since they had to find a new venue only a few weeks before the concert.

The original location--an industrial park near Woodstock, New York--pulled out only a month and a half before the event. Fortunately, two weeks later Max Yasgur agreed to rent his Bethel, New York farm as the new venue. Nathan’s Hot Dogs--Coney Island’s famous vendor--pulled out when the location of the festival was moved. Two weeks before the concert, the organizers hired Food for Love, a trio with little experience in the food business. Larger food-vending companies hadn’t wanted to take on Woodstock--no one had ever handled food services for such a large event. Many were reluctant to put in the investment required--what if the festival didn’t draw enough of a crowd to make a profit?

Woodstock’s organizers had told the Bethel authorities that they expected no more than 50,000 people. As the event drew near, with 186,000 advance tickets sold, 200,000 concertgoers seemed a more likely estimate. The organizers then hurriedly tried to bring in more toilets, more water, and more food. Woodstock would ultimately draw an inconceivable number--over 400,000 concertgoers.

The roads around Bethel became jammed for miles with people heading to the concert. Many abandoned their vehicles and made the long walk in. The plugged roads would also make it extremely difficult to get needed supplies in.

The stage, parking lots, and concession stands were barely finished in time for the event. Concert-goers started arriving two days before--with the ticket booths and gates still uncompleted. Since people were able to just walk in, the organizers were forced to declare it a free concert--creating a monumental debt for them. (Though profits from a soundtrack and movie made from films of the Woodstock Festival would help bring down the debt.)

Most concertgoers arrived expecting to be able to purchase food. Food for Love concessions were quickly overwhelmed. Food became very hard to find. The Hog Farm, a West Coast commune hired to help with security, stepped in to help. They provided free food lines serving brown rice and vegetables--and granola. For some of the crowd, granola was nothing new. But for many it was. Granola would soon become the iconic food of the hippie era.

When the people of Sullivan County, where Yasgur’s farm was located, heard reports of food shortages, they gathered thousands of food donations, including 10,000 sandwiches, as well as water, fruit, and canned goods. Concertgoers who had brought their own food shared what they had with others.

It rained off and on during the event, interrupting or delaying performances--and creating a sea of mud. There weren’t enough receptacles for garbage. People waited an hour to use one of the portable toilets--then finding it an extremely unsanitary experience when they finally reached the front of the line.

Yet--despite unbelievably crowded conditions with wall-to-wall concertgoers, massive traffic jams, serious food shortages, no running water, no telephones, no electricity (except for the performance stage--and even that was sketchy at times), lack of sufficient restroom facilities, and the muddy quagmire--Woodstock was a place of communal peace and sharing for the three days of the festival. There were no reported incidents of violence among this gathering of over 400,000 people.

What Really Mattered

In the end, Woodstock wasn’t really about the food, the weather, or even the lack of creature comforts. For many who attended, Woodstock was about experiencing three days of legendary rock and roll music, being part of a peaceful community with hundreds of thousands of other young people, and immersing yourself freely and fully in the moment. (And, yes, free love and drugs in addition to rock and roll.) The Woodstock concert logo on this flag--the guitar and dove of peace--sums up the idealism of many of Woodstock’s concertgoers.

This flag’s faded and tattered appearance seems to suggest the logistical challenges of Woodstock. But it is more likely that its owner displayed this treasured keepsake for years after--the flag couldn’t fade this much or get this tattered in just three days. Instead, this flag attests to the eternal staying power of Woodstock as a cultural landmark for an entire generation of American youth--and for the nation.

Woodstock captured, vividly and indelibly, the spontaneity and free spirit of the counterculture movement of the 1960s--and its vision of freedom and social harmony that would ignite change in American society during the coming years.

Woodstock made history.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford

Woodstock has left its “mark”--not only in memory--but in archeology. Binghamton University’s archaeology team can really “dig it.” In 2018, they determined the location of the stage. By analyzing rocks and vegetation, they also located the area of the vendors’ booths, known as the Bindy Bazaar.

1960s, 20th century, New York, popular culture, music, by Jeanine Head Miller

One Giant Leap for Mankind

Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon Landing

The Space Race began in the 1950s, when both the United States and the Soviet Union attempted to launch ballistic missiles into outer space. Americans were surprised when the Russians beat them to it, launching the Sputnik I satellite in October 1957. But, when Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin orbited earth on April 12, 1961, Americans were downright shocked and not a little concerned. As a response, President Kennedy pledged to support a more aggressive space program than President Eisenhower had initiated before him.

On May 25, 1961, President Kennedy laid out a bold vision—that America should commit itself to landing a man on the moon “before the decade is out.” When astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin A. “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr. finally did set foot on the moon on July 20, 1969, many people considered it America’s finest hour.

Learn more about these artifacts below and then see them for yourself in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation during our pop-up exhibit now on display this summer.

This pictorial souvenir card depicts President Kennedy awarding NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal to America’s first astronaut, Navy Commander Alan B. Shepard, Jr., on May 8, 1961, three days after his successful flight.

Souvenir Card, 1961. THF230121

Trading cards like these generated excitement among America’s youth about the achievements of the space program.

Topps Astronaut Trading Cards, 1963. THF230119

This “Destination Moon” mechanical bank commemorates astronaut John Glenn’s achievement of orbiting the earth in 1962.

Mechanical Bank, 1962. THF173785. (Gift of Raymond Reines, Dedicated to the Berzac Family)

Congress had to approve a massive budget increase for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to make Kennedy’s bold vision even a remote possibility.

Recruiting Advertisement for NASA, July 1962. THF230079

NASA’s Apollo 11 lunar mission captivated audiences watching the drama unfolding on television. Some even documented the events with their personal cameras.

Photographic Print, July 20, 1969. THF114240

Print made from slide, July 20, 1969. THF114242

Four months before real men landed on the moon, Snoopy appeared in a Peanuts comic strip as the “World Famous Astronaut” walking on the moon. This Peanuts Pocket Doll commemorates the 1969 moon landing.

Snoopy Toy, 1969. THF52. (Gift of CarolAnn Missant)

This coloring book included the Mercury, Apollo, and Saturn vehicles and astronauts, as well as some history of the space program.

Coloring Book, 1969. THF292641

Those who viewed the moon landing on TV on July 20, 1969, often have difficulty separating the historic occasion from the steadfast reporting of it by Cronkite—considered at the time “the most trusted man in America.”

Record Album, Narrated by Walter Cronkite, 1969. THF110908

The cover story for this issue contained an in-depth report of the historic moon-landing mission.

Time Magazine for July 25, 1969. THF230050. (Gift of the Estate of Dr. and Mrs. Martin A. Glynn)

This commemorative game, simulating the successful moon landing, had players collecting “moon rocks.”

Board Game, 1969-1975. THF91918

This phonograph record comprises a “recorded history of space exploration and the triumph of the lunar landing.”

Record Album, 1969. THF154908. (Gift of the Estate of Dr. and Mrs. Martin A. Glynn)

At the height of the Apollo space program, Marathon Gas Stations offered a series of promotional glasses featuring the Apollo 11, 12, 13, and 14 missions.

Tumblers commemorating Apollo 11 mission, circa 1969. THF175132 (Gift of Jan Hiatt)

The Apollo 11 astronauts took pieces of the 1903 Wright Flyer—the first practical heavier-than-air flying machine—on their 1969 mission to symbolize the incredible progress made in those 66 years. Here, Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong poses in front of the Wright brothers' home in Greenfield Village during a 1979 visit to The Henry Ford.

Photograph of Neil Armstrong in Greenfield Village, August 16, 1979. THF128246

The iconic image on this poster depicts Buzz Aldrin walking on the moon’s surface, a photo taken by Neil Armstrong.

Poster, 1969. THF56899

Read more

John Glenn, Space Hero

John F. Kennedy's Enduring Legacy

Donna Braden is Senior Curator & Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 2010s, 20th century, 1960s, space, by Donna R. Braden