Posts Tagged 21st century

Dale Earnhardt Iconic Victory

Pennant, "Dale Earnhardt, #3," 2000. THF251065

Dale Earnhardt Sr. is truly one of NASCAR’s greatest legends, with a total of 76 career victories and seven NASCAR Cup championships on the way to becoming a first-ballot NASCAR Hall of Famer.

But one victory, 20 years ago today, will always be special. The 1998 Daytona 500 was the race that Dale Earnhardt finally broke through and won “The Great American Race” in his 20th attempt.

Ironically, Earnhardt was considered a Daytona race master. He had won 11 Daytona 500 qualifying races, six Busch Clash races, four IROC all-star races, two 400-mile July races, and seven Grand National (now XFINITY Series) events at the famed 2.5-mile tri-oval.

That’s 30 victories at the track he loved - a place where legend was he could “see the air” in the draft of cars. It was a place where he was feared by the other competitors because he was so good in competition there.

But a series of mishaps in the biggest race of them all – the Daytona 500 – had hampered him in chasing the trophy he wanted most. Once, he won the Daytona 499 ½, cutting a tire going through the final two turns and losing the chance to win. Other times he had the dominant car only to be beaten by fuel strategy. Or he’d come runner-up in a battle to the finish line.

But that was all forgotten on Feb. 15, 1998, when Dale Earnhardt, once again dominant, led 107 of the race’s 200 laps to take his long-awaited victory in the third fastest 500 in history at that time.

The post-race scene was emotional as Earnhardt slowly rolled down pit lane, with every crew member from every team greeting him with high fives and slaps on his black No. 3 Chevrolet.

The streak had been broken and Dale Earnhardt finally got the trophy he always wanted.

Sadly, just three years later, again in the Daytona 500, Earnhardt was killed in a last lap crash in Turn 4 while attempting to block for his team cars of Michael Waltrip and his son Dale Jr., who went on to finish 1-2.

Kevin Kennedy is a guest writer to The Henry Ford.

Florida, 21st century, 2010s, 20th century, 1990s, racing, race car drivers, cars, by Kevin Kennedy

Charlie Sanders: Detroit Lions Icon

Ring received by Charlie Sanders when he was enshrined at the Pro Football Hall of Fame. THF165545

The Henry Ford has in its collection this commemorative bust and ring that had once been owned and cherished by Charlie Sanders, Detroit Lions tight end. He had received these items when he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame on August 4, 2007, along with five other players.

The Pro Football Hall of Fame was created in Canton, Ohio, in 1963, to commemorate the game and players of professional football. As of 2017, 310 players are enshrined here, elected by a 46-person committee that is mostly made up of members of the media. An Enshrinement Ceremony is held annually in August. Thousands attend this ceremony and millions more watch and listen as the nationally televised event unfolds.

Sanders is one of 19 Lions enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Seven of the 19 are African American, including Lem Barney, Barry Sanders, and Dick “Night Train” Lane.

Charlie Alvin Sanders (1946-2015) was born in rural Richlands, North Carolina, where his aunt raised him after the death of his mother when he was only two years old. At age 8, after his father got out of the military, the family moved to Greensboro—a hotbed of racial tension, most famously the Greensboro lunch counter sit-ins of 1960.

He graduated from James B. Dudley High School (Greensboro’s first all-black public school, established in 1929). There he starred in football, baseball, and basketball. His dislike of Southern racial attitudes discouraged him from attending North Carolina’s Wake Forest University; he decided instead to play football at the University of Minnesota.

The Detroit Lions chose him in the third round of the 1968 NFL Draft. Initially, he wasn’t sure about playing for Detroit after witnessing the civil unrest in that city in 1967, reminding him of the racial tensions in the South when he was growing up. He almost went to Toronto to play hockey, but the Lions offered him a contract he decided to accept.

Sanders has been considered the finest tight end in Detroit Lions history. He played for the Lions from 1968 to 1977, totaling 336 career receptions (a Lions record that would hold for 20 seasons) for 4,817 yards and 31 touchdowns. He was also known as a superior blocker.

The tight end was a unique offensive position that, depending upon the coach’s strategy, can assist with blocking for the running back or quarterback as well as receive passes. Greater use of the tight end as a receiver started in the 1960s. Sanders proved to be the Lions’ “secret weapon” in the passing game during a period when the right end was primarily a blocker. He was one of the first tight ends who brought experience in both college football and basketball, and he had great leaping ability, big hands, strength, speed and elusiveness—traits not common for tight ends of his era. Hall of Fame Cornerback Lem Barney claimed, “He made some acrobatic catches. I’m telling you, one-legged, one arm in the air, floating through the air almost like a Superman. If you threw it to him he was going to find a way to catch it.”

Sanders grew up in an era that marked the transition between legally upheld segregation in the South and increasingly prominent roles of African Americans in all aspects of sports—on the playing field, in media, and as decision-makers in coaching and management. He came of age at a time when the black athlete in Detroit aspired to a more activist role in social and business matters. He spent much time in the company of Lions teammates Lem Barney and Mel Farr and Pistons star Dave Bing. Referring to themselves as “The Boardroom,” they frequently conducted meetings in which they discussed the importance of black athletes being defined by more than simply their on-field exploits.

Sanders’ look defined African American players of the 1970s. As writer Drew Sharp remarked, “He wore the huge Afro. His helmet couldn’t cover it all. It looked cool. It looked defiant. And, quite frankly, it was the only motive for any kids in my northwest Detroit neighborhood to buy a Lions helmet at that time because they wanted their Afros sticking out from the back.” He also sported a heavy Fu Manchu mustache at the time.

Bust received by Charlie Sanders when he was enshrined at the Pro Football Hall of Fame. THF165545

During his 10 years playing for the Lions, he was chosen seven times for the Pro Bowl (NFL’s All-Star game) from 1968 to 1971 and 1974 to 1976—more than any other Hall of Fame Tight End. He was also chosen for NFL’s All-Pro team in 1970 and 1971 (made up of players voted the best in their position during those two years) and for the NFL’s 1970s All-Decade Team. In 2008, he was chosen as a member of the Lions’ 75th Anniversary All-Time Team.

During an exhibition game in 1976, Sanders injured his right knee, ending his career. After retirement, Sanders served as a color analyst for Lions radio broadcasts (1983-1988), worked with the team as an assistant coach in charge of wide receivers (1989-1996 – mentoring players who would themselves go on to earn a place in the Lions’ record book), returned to radio broadcasting in 1997, then joined the Lions’ front office as a scout. He became the team’s assistant director of pro personnel in 2000, holding that role until his death on July 2, 2015.

Sanders had also worked in the team’s community relations department and did much charitable work, serving as a spokesman for the United Way and The March of Dimes. He created The Charlie Sanders Foundation in 2007, providing scholarships for high school students in Michigan and North Carolina, and began the “Have a Heart Save a Life” program within the foundation.

Sanders spent 43 years with the Detroit Lions over parts of five decades, the longest tenure of anyone outside the Ford family. Sports blogger “Big Al” Beaton wrote about him, “…as a kid growing up in the 70’s, my favorite Lion was Charlie Sanders….We all wanted to emulate Charlie Sanders. In my mind Sanders was the best tight end I’ve ever seen play.”

Donna R. Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 20th century, sports, Michigan, football, Detroit, by Donna R. Braden, African American history

Report from the 2018 North American International Auto Show

Hot Hatch Heaven! Hyundai’s 275-horsepower Veloster N, one of several new models unveiled at this year’s North American International Auto Show.

Detroit is the capital of the global automotive industry once more as the 2018 North American International Auto Show arrives at Cobo Center. Carmakers from around the world have come to share peeks at their 2019 model lines, and hint at new technologies that may be coming in the years ahead. As usual, the exhibits range from exciting, to informative to downright unreal. This is exactly what it looks like: a 1979 Mercedes-Benz G-Class frozen in amber.

This is exactly what it looks like: a 1979 Mercedes-Benz G-Class frozen in amber.

Mercedes-Benz takes the cake for most unusual display. The German automaker unveiled a new version of its venerable G-Class SUV, in continuous production since 1979. To emphasize its endurance, Mercedes encased a vintage G-Class in a giant block of amber. (Think dino-DNA mosquitoes in Jurassic Park.) The block is located outside, along Washington Boulevard, rather than in the Mercedes-Benz booth. But don’t miss that either – you can see a 2019 G-Class splattered with faux mud, and the G-Class driven to victory by Jacky Ickx and Claude Brasseur in the 1983 Paris-Dakar Rally.

The Chevrolet Silverado – now lighter thanks to a blend of steel and aluminum body panels.

The Chevrolet Silverado – now lighter thanks to a blend of steel and aluminum body panels.

With gas prices down and the economy up, Americans have reignited their romance with pickup trucks. Chevrolet and Dodge both revealed new full-sized models, while Ford trumpeted the return of its mid-size Ranger. The 2019 Chevy Silverado rolled out under the headline “mixed materials.” In response to the Ford F-150’s aluminum bed (premiered at 2014’s NAIAS) and fuel efficiency targets, the bowtie brand is now building Silverado bodies with a mix of steel and aluminum components, shedding some 450 pounds from the truck’s overall weight. Chevy, celebrating a century in the truck business this year, is quick to point out that Silverado’s bed remains an all-steel affair. (Silverado TV commercials have been cutting on the F-150’s aluminum bed for some time now.)

Eyeing the American market, China’s GAC Motor makes a splash with its Enverge concept car.

Eyeing the American market, China’s GAC Motor makes a splash with its Enverge concept car.

China is a bigger factor in the American auto industry each year. Buick’s Envision crossover is already made in China, and Ford will shift production of its compact Focus there next year. It’s only a matter of time before a Chinese automaker starts marketing cars in the United States. GAC Motor hopes to be the first, announcing plans to sell vehicles stateside in 2019. (Yes, Chinese-owned Volvo is already selling cars here, but it first came to the U.S. in 1955 in its original Swedish guise.) It could be a tough sell – U.S. automakers and politicians aren’t too pleased with the steep tariffs imposed on American cars sent to China. In the meantime, GAC tempts NAIAS visitors with its Enverge concept SUV. The all-electric Enverge is said to have a range of 370 miles on a single charge – and can be recharged for a range of 240 miles in a mere 10 minutes.

Detective Frank Bullitt’s 1968 Ford Mustang, among Hollywood’s most iconic cars.

Ironically, one of the most talked-about cars at NAIAS is 50 years old. Ford Motor Company tracked down one of two Highland Green Mustangs driven by Steve McQueen in the 1968 thriller Bullitt. As any gearhead knows, the movie’s epic 11-minute chase scene, in which McQueen and his Mustang go toe-to-toe with a couple of baddies in a black 1968 Dodge Charger, is considered one of Hollywood’s all-time greatest car chases – even half a century later. Its lasting appeal is a credit to McQueen’s skill (both as an actor and a driver – he did some of the chase driving himself), the “you are there” feel of the in-car camerawork, and – obviously – the total absence of CGI. Those are real cars trading real paint.

The current owner’s parents bought the Mustang through a 1974 classified ad in Road & Track magazine. For years they used one of pop culture’s most important automobiles as their daily driver! With the movie’s 50th anniversary this year, the owner decided it was time to bring the car back into the spotlight. Ford agreed and, in addition to the movie car, its booth also features the limited edition 2019 Bullitt Mustang, a tribute car that hits dealer lots this summer.

Digital license plates may one day eliminate sticker tabs – or be remotely updated to alert police of a stolen vehicle.

The youngest, hungriest companies at NAIAS are on Cobo Center’s lower level. More than 50 start-ups, along with colleges and government agencies, are in Detroit for the second annual AutoMobili-D, the showcase for fresh ideas and innovative technologies. Reviver Auto hopes to revolutionize an accessory that hasn’t changed in more than a century: the license plate. The California company proposes swapping the tried and true stamped metal plate for a digital screen. The new device is more visible in low light and poor weather, and resistant to the corrosion that plagues metal plates. In lieu of adhesive registration tabs, your digital plate could be renewed remotely each year by the DMV. Plates could also broadcast Amber Alerts to other drivers, or be updated by authorities if you report your car as stolen. Some will argue that current license plates are fine – as functional and intuitive as need be. But based on the number of randomly-placed renewal tabs I see out there, I’m not so sure there isn’t room for improvement.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 2010s, technology, NAIAS, movies, Michigan, Detroit, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson

Remembering Dan Gurney (1931-2018)

Dan Gurney at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, 1963. THF114611

The Henry Ford is deeply saddened by the loss of a man who was both an inspiration and a friend to our organization for many years, Dan Gurney.

Mr. Gurney’s story began on Long Island, New York, where he was born on April 13, 1931. His father, John Gurney, was a singer with the Metropolitan Opera, while his grandfather, Frederic Gurney, designed and manufactured a series of innovative ball bearings.

The Gurneys moved west to Riverside, California, shortly after Dan graduated high school. For the car-obsessed teenager, Southern California was a paradise on Earth. He was soon building hot rods and racing on the amateur circuit before spending two years with the Army during the Korean War.

Following his service, Gurney started racing professionally. He finished second in the Riverside Grand Prix and made his first appearance at Le Mans in 1958, and earned a spot on Ferrari’s Formula One team the following year. Through the 1960s, Gurney developed a reputation as America’s most versatile driver, earning victories in Grand Prix, Indy Car, NASCAR and Sports Car events.

His efforts with Ford Motor Company became the stuff of legend. It was Dan Gurney who, in 1962, brought British race car builder Colin Chapman to Ford’s racing program. Gurney saw first-hand the success enjoyed by Chapman’s lithe, rear-engine cars in Formula One, and he was certain they could revolutionize the Indianapolis 500 – still dominated by heavy, front-engine roadsters. Jim Clark proved Gurney’s vision in 1965, winning Indy with a Lotus chassis powered by a rear-mounted Ford V-8. Clark’s victory reshaped the face of America’s most celebrated motor race.

Simultaneous with Ford’s efforts at Indianapolis, the Blue Oval was locked in its epic battle with Ferrari at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Again, Dan Gurney was on the front lines. While his 1966 race, with Jerry Grant in a Ford GT40 Mark II, ended early with a failed radiator, the next year brought one of Gurney’s greatest victories. He and A.J. Foyt, co-piloting a Ford Mark IV, finished more than 30 miles ahead of the second-place Ferrari. It was the first (and, to date, only) all-American victory at the French endurance race – American drivers in an American car fielded by an American team. Gurney was so caught up in the excitement that he shook his celebratory champagne and sprayed it all over the crowd – the start of a victory tradition.

Just days after the 1967 Le Mans, Gurney earned yet another of his greatest victories when he won the Belgian Grand Prix in an Eagle car built by his own All American Racers. It was another singular achievement. To date, Gurney remains the only American driver to win a Formula One Grand Prix in a car of his own construction.

Dan Gurney retired from competitive driving in 1970, but remained active as a constructor and a team owner. His signature engineering achievement, the Gurney Flap, came in 1971. The small tab, added to the trailing edge of a spoiler or wing, increases downforce – and traction – on a car. Gurney flaps are found today not only on racing cars, but on helicopters and airplanes, too. In 1980, Gurney’s All American Racers built the first rolling-road wind tunnel in the United States. He introduced his low-slung Alligator motorcycle in 2002 and, ten years after that, the radical DeltaWing car, which boasted half the weight and half the drag of a conventional race car. Never one to settle down, Gurney and his team most recently were at work on a moment-canceling two-cylinder engine that promised smoother, more reliable operation than conventional power plants. Dan Gurney, 2008. THF56228

Dan Gurney, 2008. THF56228

Our admiration for Mr. Gurney at The Henry Ford is deep and longstanding. In 2014, he became only the second winner of our Edison-Ford Medal for Innovation. It was a fitting honor for a man who brought so much to motorsport, and who remains so indelibly tied to The Henry Ford’s automotive collection. Cars like the Ford Mark IV, the Mustang I, the Lotus-Ford, and even the 1968 Mercury Cougar XR7-G (which he endorsed for Ford, hence the “G” in the model name), all have direct links to Mr. Gurney.

We are so very grateful for the rich and enduring legacy Dan Gurney leaves behind. His spirit, determination and accomplishments will continue to inspire for generations to come.

Hear Mr. Gurney describe his career and accomplishments in his own words at our “Visionaries on Innovation” page here.

View the film made to honor Mr. Gurney at his Edison-Ford Medal ceremony below.

engineering, Mark IV, Indy 500, Le Mans, Europe, Indiana, California, New York, 21st century, 20th century, racing, race cars, race car drivers, in memoriam, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, cars, by Matt Anderson

The Mark IV Visits the 2017 SEMA Show

Our 1967 Ford Mark IV at SEMA with the 2018 GT Heritage Edition it inspired.

It’s been a busy couple of years for our 1967 Ford Mark IV. In the last 24 months, the car traveled to England, France, California and, most recently, Nevada. Race fans have welcomed the car at each stop, excited to see it 50 years after its Le Mans win with Dan Gurney and A.J. Foyt. The car’s trip to the Silver State coincided with this year’s SEMA Show, presented by the Specialty Equipment Market Association from October 31-November 3 in Las Vegas.

The SEMA Show is among the largest automotive trade shows on the calendar. It brings together original equipment manufacturers, aftermarket suppliers, dealers, restoration specialists and more. SEMA draws some 2,400 exhibitors and 160,000 people (all of them industry professionals – the show isn’t open to the public) to the Las Vegas Convention Center each year. You’ll find a bit of everything spread over the show’s one million square feet of exhibit space: speed shop equipment, specialty wheels and tires, seats and upholstery, car audio systems, paints and finishes, motor oils and additives – basically, anything that makes a car run, look, sound or feel better. Ford provided (joyously tire-shredding) rides in Raptors, Focus RS hatches and Mustang GT350s.

Ford provided (joyously tire-shredding) rides in Raptors, Focus RS hatches and Mustang GT350s.

Our Mark IV was given an honored place in Ford Motor Company’s main exhibit, where it was paired with the 2018 GT Heritage Edition that pays tribute to the Gurney/Foyt win. Ford’s exhibits continued outside the Convention Center in the “Ford Out Front” area. Jersey barriers formed an impromptu track in the parking lot, where attendees could ride with a professional driver in a Mustang GT350, a Focus RS, or an F-150 Raptor. Believe me, you haven’t seen drifting until you’ve seen it done with a pickup truck. The American Southwest, native habitat of the Roadrunner – like this 1970 Superbird tribute car.

The American Southwest, native habitat of the Roadrunner – like this 1970 Superbird tribute car.

Of course, Ford wasn’t the only OEM in town. Chevrolet, FCA, Toyota, Audi, Honda and Hyundai all had a presence at the show. Chevy brought its new special edition Camaro, honoring the 50th anniversary of Hot Wheels diecast cars, while FCA celebrated all things Mopar. Toyota, marking the 60th anniversary of its U.S. sales arm, brought Camrys representing each of that venerable model’s eight styling generations. PPG Paints displayed airbrushed portraits of this terrorsome trio: Edgar Allan Poe, Pennywise and Herman Munster.

PPG Paints displayed airbrushed portraits of this terrorsome trio: Edgar Allan Poe, Pennywise and Herman Munster.

PPG Paints gets my vote for most elaborate show booth. Embracing SEMA’s opening date of October 31, the company built a giant haunted house, complete with cars and parts strewn about the front lawn called – what else – “The Boneyard.” The surrounding fence was decorated with incredible airbrush art celebrating Halloween heroes like Edgar Allan Poe and Herman Munster. Having a hard time finding new cassettes for your mid-1980s Buick Regal? Retro Manufacturing will sell you a perfect-match stereo with a USB port.

Having a hard time finding new cassettes for your mid-1980s Buick Regal? Retro Manufacturing will sell you a perfect-match stereo with a USB port.

More than a few vendors drew crowds to their booths with the help of celebrity appearances. Walk around and you’d spot stars from every field of automotive endeavor. There were drivers (Emerson Fittipaldi, Ken Block), television hosts (Jessi Combs, Dennis Gage), custom builders (Gene Winfield, Chip Foose), rock stars (Jeff Beck, Billy Gibbons), and all-around icons (Linda Vaughn, Richard Petty, Jay Leno, Mario Andretti). Many SEMA booths hosted live demonstrations, like this pinstriper at work on a Ford Focus RS.

Many SEMA booths hosted live demonstrations, like this pinstriper at work on a Ford Focus RS.

There were educational opportunities, too. Workshops and seminars throughout the week ranged from standard business conference fare (“Building a Sustainable Social Media Strategy”) to the decidedly SEMA-specific (“Building the Best Boosted Engines of Your Career”). If seminars aren’t your thing, you could learn by watching everything from welding to pinstriping taking place right at exhibitor booths. When is a Mustang a Lincoln? When it’s this P-51 Mustang airplane-inspired hot rod by Chip Foose, powered by a Lincoln-Zephyr V-12.

When is a Mustang a Lincoln? When it’s this P-51 Mustang airplane-inspired hot rod by Chip Foose, powered by a Lincoln-Zephyr V-12.

Contests added to the fun, too. Hot Rodders of Tomorrow, a nonprofit that encourages young people to consider careers in the automotive aftermarket industry, sponsored a challenge in which high school teams competed against each other in timed engine rebuilds. The most celebrated contest was SEMA’s annual Battle of the Builders. Nearly 200 customizers brought vehicles to be judged in four categories: hot rods, trucks/off-road vehicles, sport compacts, and young guns (for builders age 27 and under). Three top finishes were selected from each category over the show’s run, and these top 12 vehicles led the post-show SEMA cruise. An overall winner was then selected from the 12. Troy Trepanier took this year’s top prize with his 1929 Ford Model A hot rod. Tucker Tribute: A hand-built replica powered by a Cadillac Northstar V-8.

Tucker Tribute: A hand-built replica powered by a Cadillac Northstar V-8.

So ended another SEMA Show – and a successful golden anniversary tour for the Mark IV. And while it’s good to have the car back in the museum, we’re glad we could share it with so many people over the past two years. We’ll hope to see some of you again in 2067!

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Europe, 21st century, 2010s, racing, Le Mans, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, events, 1960s, 20th century, race cars, Mark IV, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson

An Old Car Festival for the Books: 2017

The Canadian Model T Assembly Team wowed Old Car Festival crowds by putting together a working chassis in less than 10 minutes.

Our 67th annual Old Car Festival is in the books – and it was one for the books this year. Postcard-perfect weather, a host of new activities and hundreds of vintage automobiles from motoring’s first decades made this one of the most exciting Greenfield Village car shows in recent memory. This yellow 1921 Lincoln, from the Cleveland History Center, is believed to be the earliest surviving Lincoln motor car.

This yellow 1921 Lincoln, from the Cleveland History Center, is believed to be the earliest surviving Lincoln motor car.

Lincoln took center stage as our featured marque. It was 100 years ago that Henry Leland left Cadillac to form what would become his second automobile company, named for the first president for whom he voted. We had a number of important Lincolns on hand. From The Henry Ford’s own collection was the circa 1917 Liberty V-12 aircraft engine (Lincoln’s first product) and the 1929 Dietrich-bodied convertible. Our friends at the Cleveland History Center’s Crawford Auto-Aviation Collection brought something very special: a 1921 Model 101 believed to be the oldest surviving Lincoln automobile. The earliest cars, like this red 1903 Ford Model A runabout, line up for their turn at Pass-in-Review.

The earliest cars, like this red 1903 Ford Model A runabout, line up for their turn at Pass-in-Review.

Automotive enthusiasts had their pick of activities. There were the cars, of course, spread chronologically throughout the village. There were the Pass-in-Review parades, in which our expert narrators commented on participating vehicles as they drove past the Main Street grandstand. There were the car games, and continuing demonstrations by the Canadian Model T Assembly Team, in Walnut Grove. There were bicycle games near (appropriately enough) Wright Cycle Company. And there were presentations on various auto-related topics in Martha Mary Chapel and the Village Pavilion. Old Car Festival welcomed a few genuinely rare cars in addition to the wonderfully ubiquitous (Ford, Chevrolet, Dodge Brothers) and downright obscure (Crow, Liberty, Norwalk). Rarities this year included a 1913 Bugatti Type 22 race car (said to be the oldest Bugatti in North America) and a 1914 American Underslung touring car (purportedly the last vehicle produced by the company). Staff presenters and show participants alike dressed in period clothing, adding to the show’s atmosphere.

Staff presenters and show participants alike dressed in period clothing, adding to the show’s atmosphere.

But this year, the cars were only the beginning. Greenfield Village hosted activities and historical “vignettes” keyed to each decade represented in the show. Aging Civil War veterans reminisced about Shiloh and Gettysburg at the Grand Army of the Republic encampment. Farther into the village, doughboys and nurses commemorated the centennial of America’s entry into the Great War. Sheiks and Shebas danced the Charleston at the bandstand near Ackley Covered Bridge. Southern blues resonated through the Mattox Home, evocative of the Great Depression’s bleakest years. Perhaps the most popular vignette, though, was the 1910s Ragtime Street Fair occupying the southern end of Washington Boulevard. Great food, games and dancing filled the street, all set to music provided by some of the most talented piano syncopators this side of Scott Joplin. It’s magical when the sun sets and the headlamps turn on, like those on this 1925 Buick Master 6 Touring.

It’s magical when the sun sets and the headlamps turn on, like those on this 1925 Buick Master 6 Touring.

Longtime show participants and visitors will tell you that the highlight comes on Saturday evening. As the sun sets in the late-summer sky, drivers switch on (or fire up) their acetylene, kerosene and electric headlamps for the Gaslight Tour through Greenfield Village. Watching the parade, it’s hard to tell who enjoys it more – the drivers and passengers, or the visitors lined up along the route. This year’s tour was capped by a fireworks display at the end of the night.

It was a special weekend with beautiful automobiles, wonderful entertainment and – most of all – fellowship and fun for those of us who love old cars. Congratulations to the 2017 Old Car Festival Award Winners.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, Old Car Festival, Greenfield Village, events, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson

Artist in Residence: Herb Babcock

Meet our next artist in residence, Herb Babcock. Tell us a little bit about yourself and your work.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and your work.

I was born in a small town in Ohio in 1946. I received a BFA in Sculpture from the Cleveland Institute of Art, Cleveland, Ohio in 1969 and an MFA in Sculpture from Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan in 1973. I studied sculpture at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine 1967 and glass at the Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio from 1970-71.

I am Professor Emeritus, College for Creative Studies. I taught at CCS for 40 years. Currently I indulge myself in the studio, conceptualizing and creating art.

Fire began to dominate my art in 1969, the first time I tried to blow glass. As a sculptor, I was forging steel into “form.” Molten glass was an alternative: a hot, quick and scary medium to make art. Once I immersed myself in the glass process, the material became a “fine art” medium for me.

As my glass skills evolved and I explored a new process, I created the Image Vessel Series in 1976. In this series, I “painted” using color and line, and “sculpted” to produce a three-dimensional image through a blown-glass vessel.

Do you have a favorite piece you’ve created?

Not one favorite piece; however, each step in the evolution of my work has produced several pieces that I believe interpret what I am trying to say.

Why do you enjoy working with glass?

The three-dimensional world is reflected light and shadow. Glass adds transparency and translucency. Together this considerably expands the vocabulary of sculpture.

Where do you find your inspiration for your creations?

Inspiration comes from the “human figure” along with its movement and stance.

What are you most looking forward to while being an Artist in Residence at The Henry Ford?

I look forward to working with the highly skilled artisans that make up the Henry Ford glass studio. I hope to produce a three- dimensional interpretation of my Image Vessel Series.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 20th century, making, Greenfield Village, glass, artists in residence, art

Lamy’s Diner Gets a Makeover

Where can you get a real diner experience, especially here in Michigan? The answer is Lamy’s Diner inside Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation—an actual 1946 diner brought here from Massachusetts, restored, and operating as a restaurant in the Museum since 2012.

Now Lamy’s Diner is more authentic, more immersive, and serving more delicious food than ever! What’s behind this makeover?

In 1984, the Henry Ford Museum purchased the Clovis Lamy's diner. It took a crane to lift the diner in preparation for transporting it from Hudson, Massachusetts. Once here, it was restored to its original 1946 appearance. THF 25768

Back in the 1980s, museum staff worked with diner expert Richard Gutman to track down an intact vintage diner for the new “Automobile in American Life” exhibit. Gutman not only found such a diner in Hudson, Massachusetts (moved twice from its original location in Marlborough, Massachusetts) but also helped in its restoration and in interviewing its original owner, Clovis Lamy, about his experiences running the diner and about the menu items he served.

Diners are innovative and uniquely American eating establishments. Lamy, like other World War II veterans, was lured by dreams of prosperity and the independence that came with being an entrepreneur of his own diner. As he remarked, “during the war, everyone had his dreams. I said if I got out of there alive, I would have another diner—a brand new one.”

This photograph shows Lamy's Diner on its original site in Marlborough, Massachusetts, 1946. The diner moved three times, first to Framingham, Massachusetts, next to Hudson, Massachusetts in 1949, and finally to the Henry Ford Museum in 1984. THF88966

Sure enough, when he was discharged from the army, he ordered a 40-seat, 36- by 15-foot model from the Worcester Lunch Car Company, a premier diner builder at that time. It boasted a porcelain enamel exterior, 16 built-in stools, six hardwood booths, a marble counter, and a stainless steel back bar. Lamy could choose the diner’s colors, door locations, and outside lettering. He and his wife Gertrude visited the Worcester plant once a week, eager to check on its construction.

Clovis Lamy stands behind the counter of his diner in Massachusetts. His favorite part of running a diner was talking to his customers. THF 114397

Lamy’s Diner opened for business in April 1946, in Marlborough, Massachusetts. As Lamy remembered, business was brisk:

We jammed them in here at noon—workers from the town’s shoe shops—and we had a good dinner trade too… People stopped in after the show…[and] after the bars closed, the roof would come off the place.

During the long hours of operation (the place closed at 2 a.m.), the kitchen turned out everything from scrambled eggs to meat loaf. To Clovis Lamy, there was no better place than standing behind the counter talking to people.

But the dream had its downside. The work day was long. He was seldom able to eat with his family. After moving the diner to Framingham, Massachusetts, he sold the business in 1950. The new owner moved it down the road to Hudson.

Lamy’s Diner exterior as it looked in the Museum in 1987. THF 77241

When Clovis Lamy and his wife viewed the diner at the 1987 opening for “The Automobile in American Life” exhibition, they confirmed that it looked as good as new. “Even the sign is the same,” he remarked later with a tear in his eye.

Lamy’s Diner interior as it looked in the Museum in 1987. THF 3869

For 25 years, no food was served at Lamy’s Diner in the museum. It was interpreted as a historic structure, until the opening of the new “Driving America” exhibit in 2012, when museum staff decided to once again serve diner fare there. Delicious smells of toast and coffee wafted out of its doors, while the place hummed with activity. Museum guests sat in the booths, on stools at the counter, or at tables on the new deck with accessible seating. They could choose entrees, beverages, and desserts from a menu that was loosely inspired by diner fare of the past.

Then, in 2016, Lee Ward, the new Director of Food Service and Catering, came to me and posed the question, what if we served food and beverages at Lamy’s that more closely approximated what customers would have actually ordered here in 1946? The diner is already an authentic, immersive setting. What if we took it even further and truly transported guests to that time and place? I have always believed in the power of food to both transport guests to another era and to serve as a teaching tool to better understand the people and culture of that era. Over the years, I’ve helped create Eagle Tavern, the Cotswold Tea Experience, the Taste of History menu, the Frozen Custard Stand, and cooking programs in Greenfield Village buildings. So I excitedly responded, sure, we could certainly do that!

But, as the chefs and food service managers at The Henry Ford began to ply me with endless questions about the correct menu, recipes, and serving accoutrements for a 1946 Massachusetts diner, I realized I needed help.

Dick Gutman talking to Lamy’s staff.

Fortunately, help was forthcoming, as Richard Gutman—the diner expert who had found Lamy’s Diner for us in the 1980s—was overjoyed to return to the project and give us ideas and advice. And the 300-some diner menus he owned in his personal collection didn’t hurt either. In fact, they became our best documentation on diner foods and what they were called in 1946, as well as the graphic look of the menus.

Cookbooks of the era offered actual recipes for the dishes we saw listed on the menus, while historic images of diner interiors provided clues as to what the serving staff might wear, what kinds of dishes customers ate on, and what was displayed in the glass cases on the counter.

All of these are reflected in the current Lamy’s Diner experience. Here’s a glimpse of what you’ll encounter when you visit Lamy’s after its recent makeover:

New Lamy’s Diner menu, front and inside

Kids’ menu

New England Clam Chowder, a signature dish in New England diners and here at Lamy’s

Chicken salad sandwich, using a recipe from the 1947 edition of the Boston Cooking School Cookbook, a pioneering cookbook that offered practical recipes for the average housewife.

Meat loaf plate, using Clovis Lamy’s original meatloaf recipe

Milkshake, which in Massachusetts is a very refreshing drink made of milk, chocolate syrup, and sometimes crushed ice (no ice cream), shaken until it is creamy and frothy.

Toll House cookies, invented by a female chef named Ruth Graves Wakefield in 1938, at the Toll House Inn in Whitman, Massachusetts.

Peanut butter and marshmallow fluff sandwich, a New England specialty based upon Archibald Query’s original marshmallow creme invention and later called “Fluffernutter”

Prices are, by necessity, modern, but typical prices of the era can be found on the menu boards mounted up on the wall, based upon Lamy’s original menu and prices.

So, for a fun, immersive, and delicious experience, check out the makeover at Lamy’s Diner!

In Other Food News...

A Taste of History: Now featuring recipes and menu items guests might see prepared in Greenfield Village historical structures, such as Firestone Farm and Daggett Farmhouse.

Mrs. Fisher's Southern Cooking: The menu is based solely on Mrs. Fisher's 1881 cookbook or authentic recipes.

American Doghouse: New regional hot dog options are available, from the Detroit Coney and Chicago dogs to the California dog wrapped in bacon and avocado, tomato and arugula.

Donna R. Braden, Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford and author of this blog post, has decided that her new favorite drink is the refreshing Massachusetts version (without ice cream) of the chocolate milkshake. She thanks Richard Gutman and Lee Ward for their enthusiasm and support in making this makeover possible.

Massachusetts, 21st century, 2010s, 20th century, 1980s, 1940s, restaurants, Henry Ford Museum, food, Driving America, diners, by Donna R. Braden, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Balenciaga across the Pond

The artifacts you see when you visit Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation or Greenfield Village only represent 5-10% of our object collections, and an even smaller percentage of our archival collections. The rest of our collections live in storage, but we try to find ways to make them accessible to the public by means of temporary exhibits, our Digital Collections, and loans to other institutions.

We currently have 233 artifacts, ranging from coffee pots to airplanes, on loan to 39 different institutions around the world, and we’ve just digitized a number of artifacts, such as this circa 1955 hat worn by Elizabeth Parke Firestone, that we have loaned to the V&A Museum in London for their upcoming exhibit Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion, about fashion designer Cristóbal Balenciaga.

Visit our Digital Collections to learn more about artifacts you won’t see when you visit our campus—or explore more garments and accessories by Balenciaga.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

2010s, fashion, events, Europe, digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl, 21st century, 20th century

Thank You, Bruce

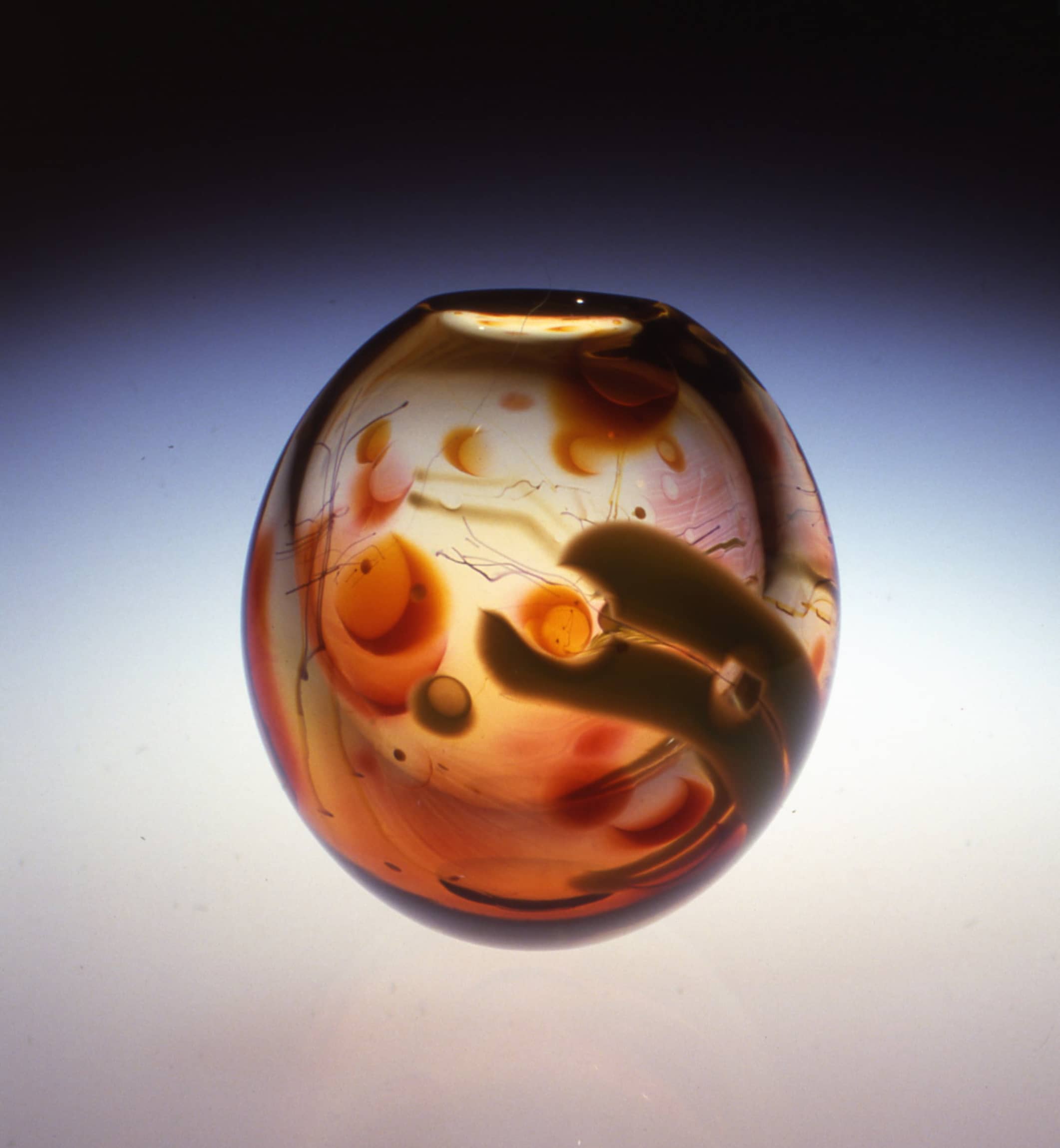

On Wednesday, March 22nd, 2017, a dear friend of The Henry Ford, Bruce Bachmann, passed away. I’ve known Mr. Bachmann since February 2010 when I was welcomed into his Glencoe, Illinois home. Bruce and his late wife Ann invited me to see their spectacular collection of studio glass. I was struck by their gracious hospitality and passion for studio glass. Sociable and gregarious, the Bachmanns loved to talk about their studio glass “family,” a network of artists, collectors, and gallery owners. Over time, the relationship grew into a friendship and ultimately, the donation of the Bachmann’s collection to The Henry Ford in 2015. This collection is the heart of the recently opened Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. A significant portion of the upcoming Davidson-Gerson Gallery of Glass in Greenfield Village, opening this spring, features masterpieces from the Bachmann’s collection.

This piece of studio glass, shown above, from Richard Royal’s Relationship Series, was a favorite of Bruce and Ann Bachmann. It lived in their master bedroom and was one of the first pieces they saw as they awoke every morning, a warm reminder of familial relationships. The artist describes the piece as the abstracted arms of a mother and father holding a child. The Bachmanns were devoted to their four children and grandchildren, likewise they saw their relationship with The Henry Ford as an extension of their own family, and a place where families gather and spend time together.

Bruce will be missed by all of us at The Henry Ford who have worked closely with him over the past seven years. A link to his obituary can be found here. See more pieces from the Bruce and Ann Bachmann Glass Collection in our digital collections.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford.

Illinois, 21st century, 2010s, in memoriam, Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, glass, by Charles Sable