Posts Tagged by aimee burpee

Exploring the Depths of Our Collections

Preserving the past is resource-intensive, and The Henry Ford actively seeks grant funding to support its mission "to provide unique educational experiences based on authentic objects, stories, and lives from America's traditions of ingenuity, resourcefulness, and innovation." Some of these grants focus on enhancing collections storage, stewardship, and accessibility — both physical and virtual. In late summer 2024, the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) awarded The Henry Ford a two-year grant to clean, rehouse, and create digital records for artifacts related to power and energy, mobility and transportation, and communications and information technology.

Building on the progress made by previous grants, this project will focus on approximately 325 artifacts housed in The Henry Ford's Central Storage Building that require attention in these key areas. The Henry Ford is currently investing in upgrades to the HVAC system in the building, which will improve the ability to regulate the storage environment. In conjunction with those improvements, the grant work will address overcrowding and previous environmental issues, which in some cases have led to dirt, mold, and other forms of artifact deterioration. Each artifact will be moved, cleaned, and assessed for conservation needs. Registrar staff will update or create catalog records, working closely with curatorial staff to research additional context.

IMLS grant team members meet to discuss work progress. / Photo by Aimee Burpee

Of the 325 artifacts, about 100 priority artifacts identified by the curators will undergo conservation treatment to digitization standards, will be photographed at high resolution and made available online through The Henry Ford's Digital Collections. Curators and associate curators will create digital content, such as blog posts, to highlight these artifacts. Additionally, curatorial staff will write descriptive narratives for the website, providing essential historical context for public audiences.

The IMLS Collections Specialist takes a reference image of each artifact for the catalog record, such as this 1915 Gentry and Lewis V-8 Automobile Engine for the Model T (left), then, after conservation intervention, Photography Studio staff photographs this priority artifact for publication on digital collections. / Photo by Colleen Sikorski (left), THF802658 (right)

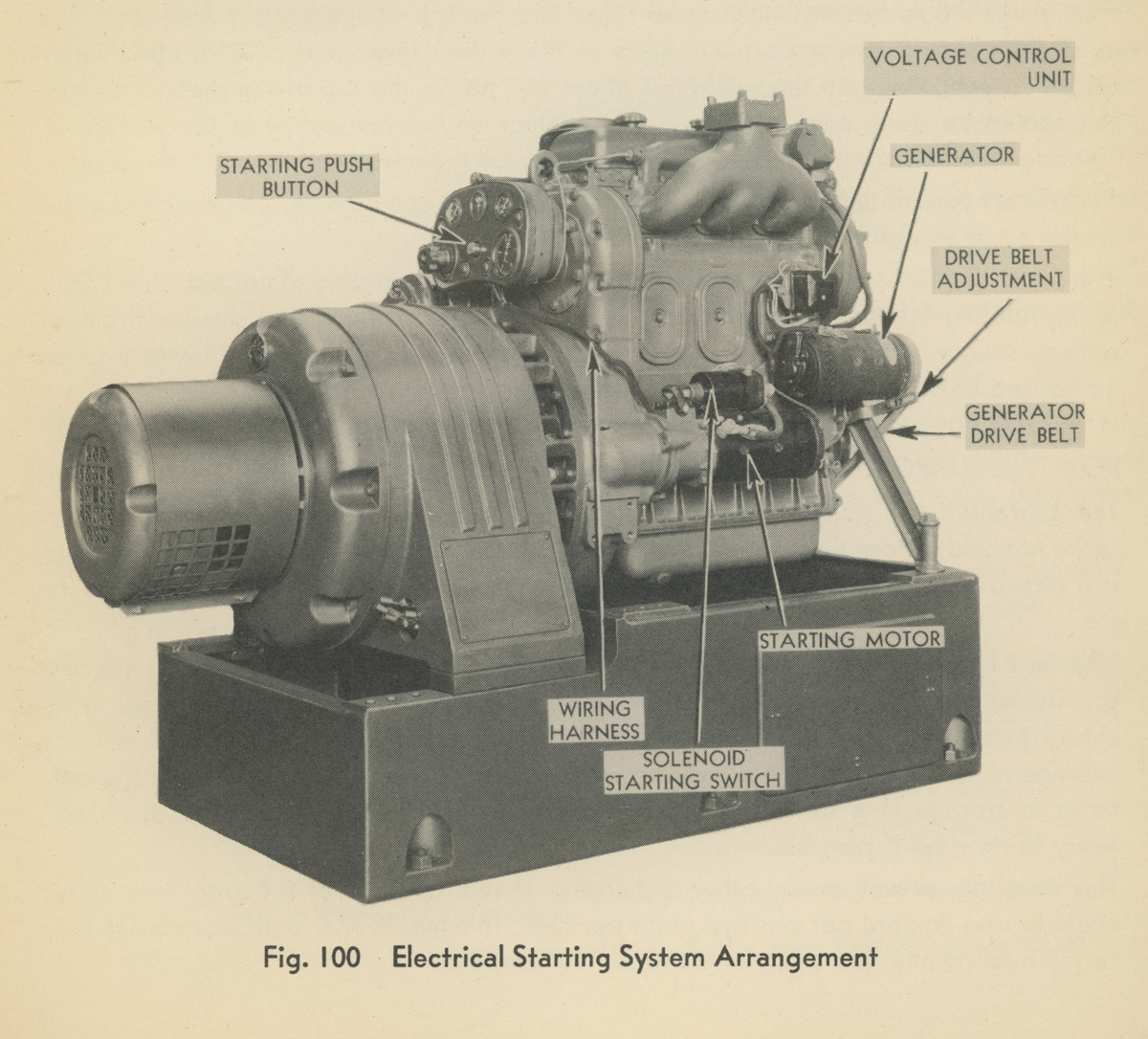

Work on the grant began in the fall of 2024, and the first priority artifact to be conserved is a six-cylinder General Motors 6-71 diesel engine — a legend in its own right. Introduced by General Motors' diesel engine division in 1938, the two-stroke unit powered everything from farm tractors and stationary generators to trucks and buses (including the 1948 GM bus on which Rosa Parks made her historic stand). GM produced variants with two, three, four, six, eight, twelve, sixteen, and twenty-four cylinders, practically guaranteeing there was a Detroit Diesel in whatever size and with whatever horsepower a customer required.

For 40 years, this GM 6-71 engine provided faithful service aboard Jacques Cousteau's ship Calypso / THF802646

The Henry Ford's Detroit Diesel just so happened to be used on one of the most celebrated scientific vessels of the 20th century: Calypso, the former World War II minesweeper converted into a floating laboratory by French oceanographer Jacques Cousteau. From 1950 through 1997, Calypso traveled the world's oceans for Cousteau's research, and for shooting many of his documentary television series and films. Calypso even visited the Great Lakes in 1980, when it traveled from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River to Duluth, Minnesota, some 2,300 miles away.

It's important to note that The Henry Ford's engine was not Calypso's source of propulsion. The ship's propellers were driven by two eight-cylinder General Motors diesel engines. Our six-cylinder engine was one of two units that ran the generators that produced electricity. Our engine didn't make the boat go, but it kept the lights on — arguably just as important a task. Of course, it wasn't just lights. Calypso's electric generators powered pumps, hydraulic systems, steering mechanisms, radar and navigation devices, and video equipment, among other necessities.

By the time our engine was decommissioned in 1981, it had been used on Calypso for 40 years, with an estimated 100,000 service hours under its belt. Calypso received two brand-new Detroit Diesel engines as part of a wider refurbishment in anticipation of a voyage to the Amazon River. General Motors gifted the decommissioned engine to The Henry Ford in 1986.

Vintage illustrations, like this one from a 1939 GM manual, guided efforts to conserve the Calypso engine. / THF721888

Through the IMLS grant project, conservators were able to clean the engine of accumulated dirt and dust, treat worn paint, and stabilize damaged gauges and controls. We were also able to replace a long-missing panel surrounding the starter button. Using period General Motors catalogs and manuals in the Benson Ford Research Center, we were able to design and 3D-print a new surround. Once the panel was painted to match, it became visually indistinguishable from the engine's original metal components. (Conservator notes, and inscriptions on the pieces themselves, identify replacement parts so as not to cause confusion in the future.) With that work done, the engine was photographed and given a new and much improved set of digital images on the website.

The Calypso Detroit Diesel is only the first of many important artifacts that will benefit from the IMLS grant and our ongoing work in the Central Storage Building. Stay tuned for future stories. It's a project that promises to be its own voyage of discovery.

This blog was produced by Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation, and Aimee Burpee, Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Think about the dishes, bowls, and mugs you often see in diners and restaurants. What are they like? And why are they designed that way? Diner or restaurant ware is typically made from porcelain or stoneware that has been “vitrified,” turning the material into a glass-like substance via high heat and fusion alongside the glaze.

Restaurant ware is designed for practicality. It is thick and sturdy with smooth and rounded contours, which offers a range of benefits. Restaurant ware is durable, less prone to breaking and chipping, and better at retaining heat to keep food warm. It also can handle extreme temperature changes. The vitrification process minimizes silverware marks on the surfaces, keeps harmful chemicals from leaching into food through food-safe glazes, and resists staining and odors. Plus, the glazes are easy to clean, commercial dishwasher safe, and maintain their glossy finish after many washes.

Stacks of plates, saucers, and bowls at the ready for guests at Lamy’s Diner in Henry Ford Museum. / Photo by Aimee Burpee

History of Restaurant Ware

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, people dining outside the home became more common. Early restaurants and diners served meals on fragile porcelain, porous earthenware, or glass not designed to handle the wear and tear of heavy daily use. As a result, pottery companies began experimenting with stoneware, first creating “semi-vitreous” pieces before moving to fully “vitreous” (or glass-like) ceramics.

Customers eating and drinking using commercial restaurant ware at the counter inside Lamy’s Diner at its original location in Marlborough, Massachusetts. / THF114397

Buffalo Pottery

One of the first and most notable companies to pursue this industry was Buffalo Pottery, based in Buffalo, New York. Founded in 1901 by soap manufacturer John Larkin, the company initially aimed to produce wares that could be given away as premiums for purchasers of his soap products. Buffalo Pottery produced its first restaurant ware pieces in 1903.

The blue-plate special – a discount-price meal that changed daily – seems to have been named after the plate that it could be served on. This plate with divided sections was made by Buffalo China circa 1930. / THF370830

Incorporated in 1940, Buffalo Pottery changed its name to Buffalo China Inc. in 1956. In 1983, It became a subsidiary of American tableware company Oneida, Ltd. After more than a century of manufacturing, the Buffalo factory was sold in 2004, marking the end of its production.

Buffalo Pottery was also known for its art pottery, decorated by artists and craftspeople to showcase artistic aspirations on utilitarian pieces like this candlestick decorated by Mabel Gerhardt in 1911. / THF176916

Syracuse China Company

Another significant manufacturer in restaurant ware production was Syracuse China Company, which originated as the Onondaga Pottery Company in 1871 in Syracuse, New York. The company initially made non-vitrified dinnerware, used both in homes and in restaurants. In 1896 they introduced vitrified stoneware with a rolled edge. By 1924 Syracuse China built a factory dedicated to manufacturing only commercial ware

After World War II, many US corporations, like General Motors, built engineering and manufacturing campuses that included employee cafeterias. Companies such as Syracuse China made dishes, bowls, and mugs or cups with companies’ logos for use in these cafeterias. / THF194982

Syracuse China made dishes for Sears Coffee Houses, small diner-style eateries inside Sears department stores. / THF195542

In 1966 Onondaga Pottery Company officially changed its name to Syracuse China Corporation. In 1993 it became Syracuse China Company, before being acquired in 1995 by Libbey, Inc. a U.S.-based glass manufacturer. By 2009 all production was moved out of North America, bringing an end to 138 years of production in Syracuse.

Restaurant Ware Patterns

Restaurant ware was typically plain or minimally decorated with color and simple patterns. Many companies produced similar designs, allowing diners and restaurants to easily buy replacements or additional pieces from a variety of manufacturers. One popular design was a white background with one to three green stripes.

The white with green stripes pattern on a bowl by Homer Laughlin China Company, 1966 (left) and on a divided plate by Buffalo China Company, 1952 (right). / THF197347 (left), THF197410 (right)

A variation on the green-and-white theme was a design of wave-like or scallops along the rims of bowls, plates, or mugs. Shenango China, America’s second-largest manufacturer of food service wares, called their pattern Everglade. Buffalo China offered a version called Crest Green, while Mayer China referred to theirs as Juniper, and Syracuse China called it Wintergreen.

Shenango China Co.’s Everglade pattern on a cup and saucer, 1961 / THF102560

Another distinctive pattern called “Pendleton” featured a deep ivory or tan base with three stripes: red, yellow, and green. This design was likely inspired by blankets manufactured by Pendleton Woolen Mills since the early 1900s. The Glacier National Park blanket’s colors and markings are reminiscent of those distributed at frontier trading posts in exchange for furs.

Pendleton-pattern ware on display in Henry Ford Museum (left), and a Buffalo China Company cup. / Photo by Aimee Burpee (left), THF197343 (right)

Victor Mugs

Picture a mug of coffee at your local diner. Is it a mug that looks like this?

Victor Insulator mug from the Rosebud Diner in Somerville, Massachusetts. / THF197331

In the late 19th century, Fred M. Locke started Locke Insulator Company (later Victor Insulators) in Victor, New York, to manufacture glass and ceramic insulators for electrical and telegraph wires. By the mid-1930s, the plant in Victor had been retooled with four new kilns when the company was considering expanding into heavy-duty, high-quality dinnerware.

Ceramic and glass insulator made by Locke’s company in Victor, New York, circa 1898, and used on early transmission lines in the San Joaquin Valley, California. / THF175272

When WWII broke out, the U.S. government put out a call for durable dinnerware for use aboard naval ships. The Navy needed coffee mugs that were less likely to slide off surfaces, but if they did, could withstand the fall. Victor Insulators won the contract and began producing thick-walled, straight-sided handleless mugs, each with a rough ring on the bottom. Drawing the company's expertise in insulator technology, these mugs were crafted from high-quality clays fired at 2,250°F. The mugs proved so successful with the Navy that Victor quickly began making mugs with handles for the war effort. The handles were attached by one of three women employed at the factory for that specific task. The mug’s design also evolved, with the introduction of curved sides that made it easier to grip. After the war, these durable mugs were in high demand for diners and restaurants across the United States.

For several decades, Victor mugs were a staple of American dining. But by the 1980s, cheap knockoffs flooded the market, and Victor Insulators found it difficult to compete. By 1990 the company phased out the mugs, although they continue to produce ceramic insulators to this day.

Hot coffee and slice of cherry pie served at Lamy’s Diner on Homer Laughlin China Company mug and plate. / Photo by Aimee Burpee

Aimee Burpee is Associate Curator at The Henry Ford

Americans on Ice: Skating and Skate Technology in the United States

Archeological evidence suggests that ice skating began as early as 4,000 years ago in northern Europe. Travelling on foot in winter across snowy, icy landscapes for trade, hunting, and community gatherings was slow and exhausting. People first used sharpened animal bones attached to footwear by leather strips, along with poles, to propel themselves across frozen rivers, ponds, and lakes – faster and less taxing during harsh winter months.

Currier & Ives published this lithograph in 1868 of skaters on a frozen lake or pond at night, skating by moonlight. / THF118602

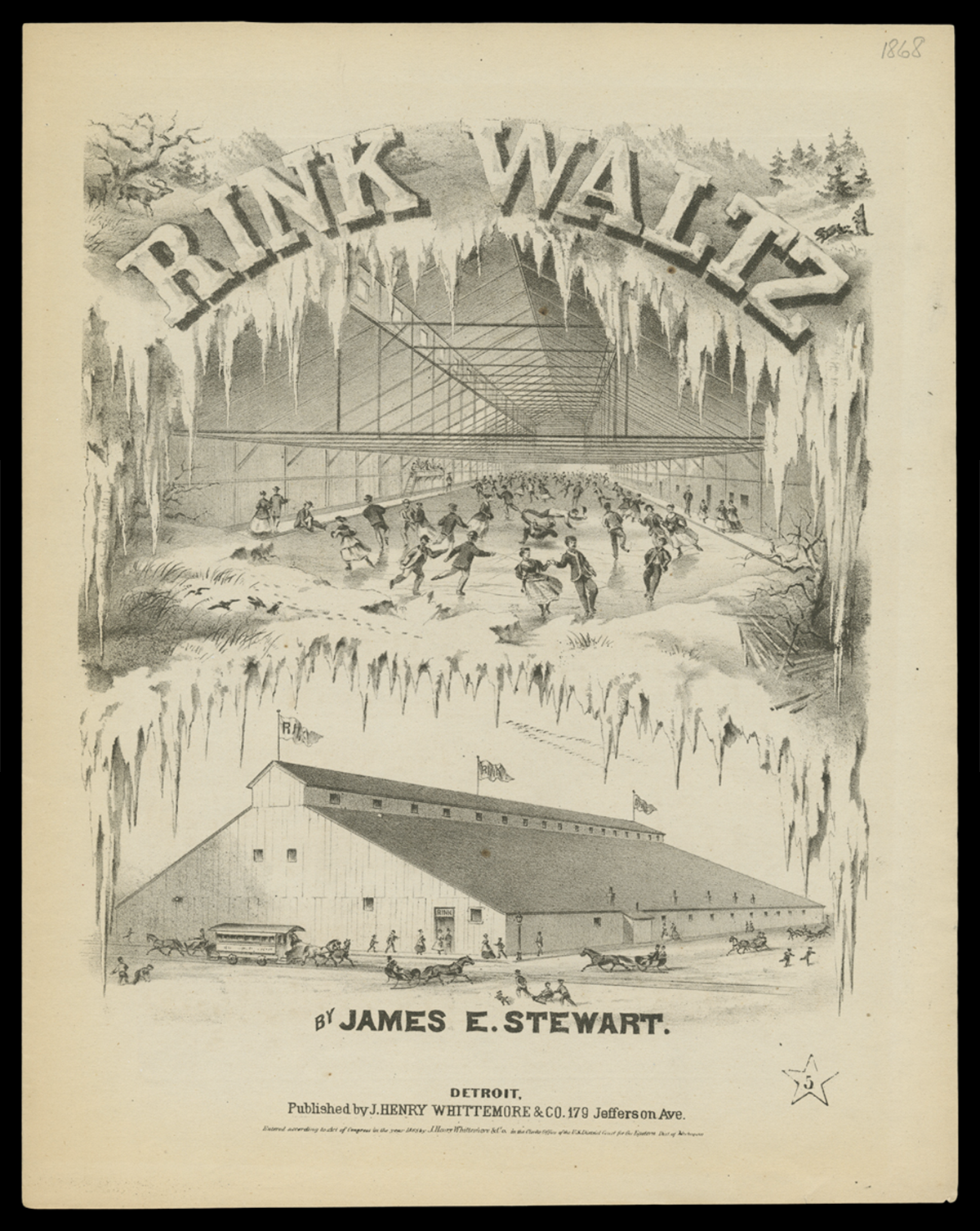

As a pastime, ice skating became popular in the United States in the mid-19th century. Initially, people skated on frozen local rivers and ponds, but as artificial ice-making improved, skating moved indoors to purpose-built rinks. Temperature-controlled buildings and artificial ice technology made it possible for ice skating to spread south and west from New England and the Upper Midwest. Skating clubs started forming across the country as early as 1849, and these clubs hosted evening skating events with live musical accompaniment .

The song Rink Waltz was written and published in Detroit in 1868. Its cover has interior and exterior renderings of the Detroit Skating Rink, which opened in 1866. / THF720452

Ice skating’s popularity peaked in the 1860s and 1870s. During this time, many patents for skates were issued to ice skate manufacturers. Publications on skating skills and safety, along with songs about skating, became widespread. Other products, such as handheld kerosene lanterns to illuminate outdoor skating at night, also show how ingrained skating had become in American culture. Women in particular embraced ice skating, which was promoted as healthy exercise and one of the few athletic activities socially acceptable for women at that time.

Lighting companies such as R.E. Dietz patented small kerosene lanterns for nighttime skaters, particularly women. / THF802186 (left), THF802187 (right, crop)

Improving Skate Technology

Early skates were made using animal bones. In the 13th and 14th centuries, craftspeople started to fabricate metal blades, which were inserted into wooden platforms. Straps, ropes, or ties secured the platform to skaters’ everyday footwear. These early blades were long and curled up in front of the toes, helping the skater navigate uneven and rough ice on frozen waterways. This type of skate was likely the kind first imported into the United States from Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Blacksmiths and carpenters in northern American towns and cities also produced skates, and some skaters even made their own.

Ice skates with crude wood platforms, curled metal blades, and leather straps. / 29.1871.2, From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Photo by Aimee Burpee.

Unfortunately, ties or straps were often unreliable. They did not secure the foot and shoes firmly in the skates, as the foot could slide side to side or even slip off the platform. To improve the attachment, manufacturers and craftspeople added a metal spike on the top of each wooden platform, which went into the heel of the shoe, and occasionally small spikes in the forefoot for additional attachment.

These Douglas, Rogers & Co. skates with 1863 patent date have a spike in the heel to attach the shoe to the platform, and tempered metal blades. Straps went through the holes in the sides of the platforms / THF802180

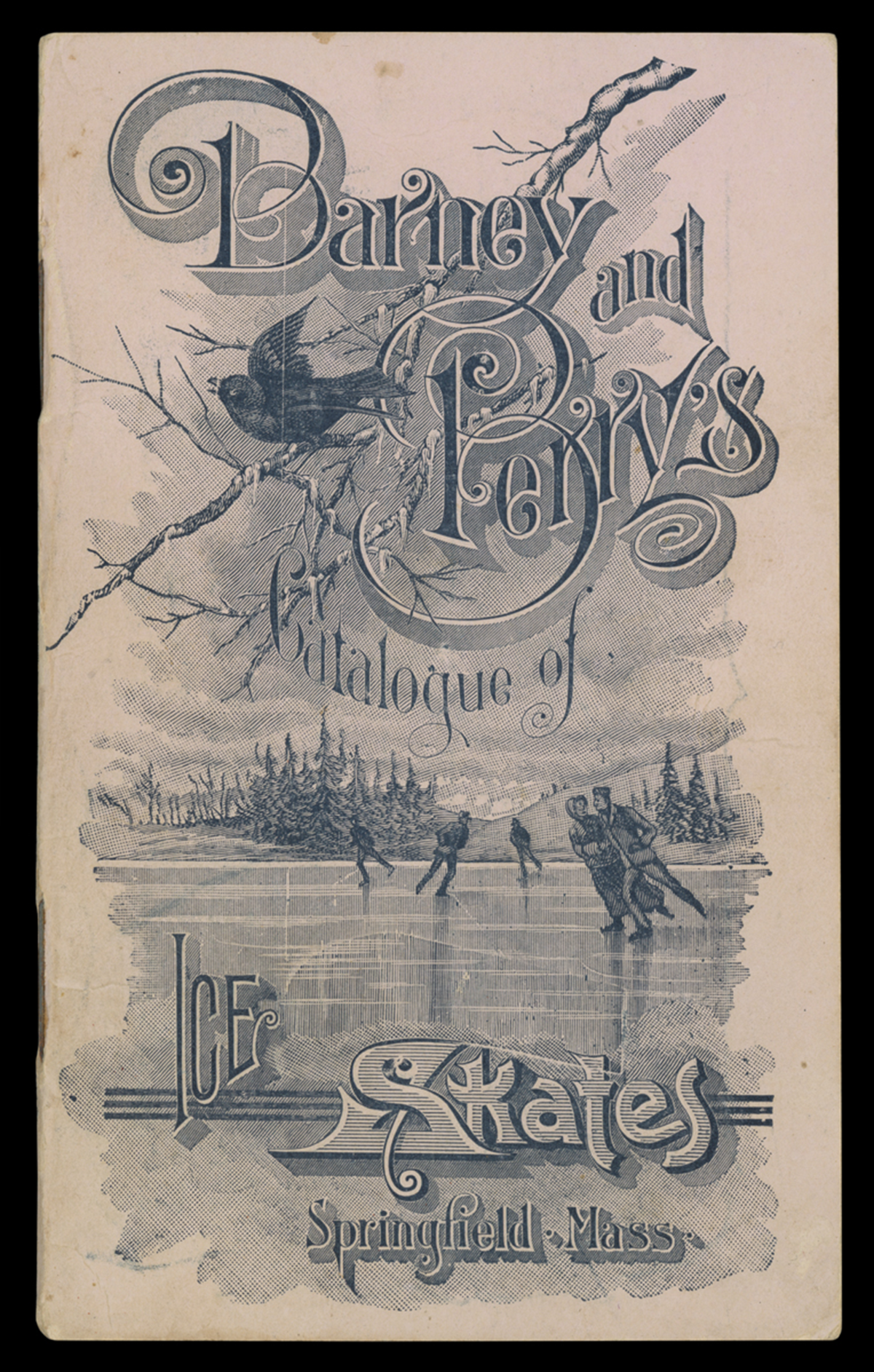

Eventually metal platforms replaced wooden ones, which cracked or splintered and required frequent repairs. The earliest metal platform skates still used ties and straps, but eventually switched to keys and clamps that more securely attached and tightened the skates to the wearer's shoes. By the 1890s, fully metal skates allowed people to simply “step into” the skate, with automatic clamps securing the skate around the shoes. These metal skates were stronger and more dependable, making them especially appealing to the rapidly growing market of hockey players and early figure skaters.

Barney & Berry patented these skates 1896, with clamps that hooked around the shoe when you stepped into them, no fiddling with straps or tightening with a skate key was necessary. / THF802173

Barney & Berry was one of the top innovators and manufacturers of ice skates. Hardware, sporting goods, and toy stores could choose models and styles from this 1894-1895 wholesale catalog to sell to customers. / THF720461

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, ice skates became one-piece boots, resembling the skates we use today. These skates provided greater support and stability, with the blade attached to a steel sole and integrated into a boot. While earlier skates started the development of specialized skates for figure skating, hockey, and speed skating, the one-piece boot skate further refined these specializations.

Children and adults could rent skates from the Belle Isle Pavilion and skate on adjacent Lake Takoma on Belle Isle in Detroit, Michigan, around 1900. / THF119081

These all-in-one boot skates belonged to Henry Ford. He enjoyed skating on a frozen pond on his Fair Lane property in Dearborn, Michigan / THF166350

Today, figure skates combine slim leather boots with toe picks for spins and jumps. Hockey skates have shorter blades for quick maneuvering, with padded foot and ankle protection. Speed skates feature longer blades and a more streamlined boot profile to decrease wind resistance.

The skates of the past led to the skates of today. And the skates of the future will continue to evolve as innovative technologies, designs, and materials are developed and implemented.

Aimee Burpee is Associate Curator at The Henry Ford

The Art of Provenance Research: Playing Detective in Our Collections

Thomas Edison Punching the Time Clock at His West Orange, New Jersey Laboratory, August 27, 1912. Read on for more on this provenance research story! / THF108339

As my colleague Laura Lipp discusses in her blog post on cataloging, The Henry Ford’s registrar’s office sometimes “plays detective” by engaging in provenance research to determine the history of the ownership of an artifact – and to deepen our knowledge of the stories behind our artifacts.

First, a little background on our early collecting.

In the 1920s and 1930s, The Henry Ford received thousands upon thousands of artifacts from sources all over the country. Staff at that time attached paper and metal tags to the artifacts, writing their source information (either the donor or the point of purchase) on the tags. They also typically included the geographic location of the source and a date. In the 1950s, staff began to catalog the collection, assigning object identification numbers (“object IDs”) and creating files that held any documentation or correspondence about the artifacts. The object ID is the unique number assigned to an artifact that indicates what year the artifact came in, and links it to its “provenance”—the source it came from and any associated stories.

On occasion over the years, staff encounter artifacts that have lost their tags, or the tags have crumbled or become illegible, so the artifacts have been disassociated with their histories. At this point, the detective work begins, to figure out the artifact’s provenance. We have many internal resources at hand to perform provenance research – our catalog database, our files and correspondence, photographs of artifacts, inventories, original cataloging cards, and more. We also use the Internet, oftentimes turning to online genealogical databases of census and demographic records.

An example of disassociated artifacts came up one day when someone wanted to know what artifacts we had related to Alexander Hamilton (can’t imagine why). Curator of Decorative Arts Charles Sable and I started looking into it. Upon searching our database, we discovered that we had received some silver that descended in the Hamilton family to Alexander and Eliza’s great-great granddaughter, Mary Schuyler Hamilton: a “sugar bowl” and candlesticks. Unfortunately, the lost tags meant we had to work through all our silver records to see what might match.

We looped in Image Services Specialist Jim Orr and he found a photo of these silver artifacts taken around the time they arrived at our museum. Now we at least knew what they looked like! The sugar bowl was not a sugar bowl – with its pierced sides, the sugar would have leaked out. We expanded our search to other silver bowls and dishes, and the curator and I came across a record for a “sweetmeat” dish that sounded promising. The record had a silver project inventory number and a location. After a quick trip to one of our storage rooms, lo and behold, the “sweetmeat dish,” a bit tarnished, matched the artifact in the image! One down, candlesticks to go.

Sweetmeat Dish, Used by Alexander Hamilton, 1780-1800 / THF169541

After an unsuccessful stop in a storage area where there are many candlesticks, I returned to my desk and started going through all our silver candlestick records. Just as I was getting ready to call it a day, I reached a record, took a double-take, and called the curator over from his office to look at it. “OH MY …!” was the exclamation all my co-workers heard, “YOU FOUND THEM!” We reunited the candlesticks with the sweetmeat dish, had them photographed, and they are now viewable online. I can easily state that was one of my proudest days.

Candlesticks, Used by Alexander Hamilton, 1780-1800 / THF169539

Most of the time, we know who donated artifacts, and where the donors lived. When looking to further document these artifacts in our collection, we do research into the donors to fill in information that wasn’t originally captured. While working on a project related to agricultural equipment, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment Debra Reid and I were interested in learning more about some artifacts that were donated by Iva and Ruby Fuerst, such as this potato digger and this hand dibble.

Potato Digger Donated to The Henry Ford by Iva and Ruby Fuerst / THF97302

Digging into the Internet and genealogical records, I was able to reconstruct a small family tree. Ruby and Iva’s grandparents, Lorenzo and Barbara Fuerst, immigrated from Germany and were farmers in Greenfield Township (now Detroit) starting in the late 1850s. After the passing of Barbara in 1905, Iva and Ruby’s father Jacob, who had an adjacent farm, continued farming in that area until he sold it in 1918 and bought a farm in Novi Township. We now know that some of the equipment was likely used first on the farms in Detroit and later in Novi. Ruby and Iva, with no heirs to pass the land to, sold most of the Novi farm to the city around 1970. It is now known as Fuerst Park, and you can find a photo of young Ruby and Iva in this brochure.

Hand Dibble Donated to The Henry Ford by Iva and Ruby Fuerst / THF171836

It's not just 3D artifacts that need provenance research, but also some of our archival holdings. One day, staff encountered some timecards in the archives that appeared to have been used by Thomas Edison. Curious to know more and hopeful to verify that exciting association, Registrar Lisa Korzetz investigated the matter and was able to find correspondence with the donor, Miller Reese Hutchinson, chief engineer at Edison’s West Orange Laboratory. Hutchinson details in his letter that the four timecards he was donating were the first four cards used by Edison in 1912 after Hutchinson had installed a new time clock at the laboratory. He also donated a photograph of Edison using the timecards at the time clock. Hutchinson was determined for a week to try to capture Edison using the timecards and clock, and finally succeeded on the last day of the week!

Time Card Punched by Thomas Edison at His West Orange Laboratory, for the Week Ending August 27, 1912 / THF108331

Today, when cataloging new artifacts for the collection, we document the provenance via the background information that the curator gleans from the donor or point of purchase. We do additional research to verify and fill in any historical background. We apply the object ID directly to the artifact in a manner approved by Conservation – different methods on different materials. We also make sure the number is discreet and easily reversible – meaning it can be removed without any adverse effects to the artifact. By using these standard museum practices to document and identify artifacts, we assist our curatorial colleagues in their pursuit to interpret and exhibit our collections to the public.

Continue Reading

digitization, collections care, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, #digitization100K, research, by Aimee Burpee