Posts Tagged by katherine white

Gilbert Rohde and D.J. De Pree: The Partnership that Modernized the Herman Miller Furniture Company

Brochure for Chicago Merchandise Mart Exhibit, "Herman Miller Modern for Your Home," 1935-1940 (THF229429)

West Michigan is known for its furniture. Furniture factories-turned-apartment or office buildings can be seen throughout Grand Rapids and its surroundings—some with company names like Baker Furniture, John Widdicomb Co., and Sligh Furniture still visible, painted on the brick exterior. While fewer in numbers today than in 1910, West Michigan still boasts numerous major furniture manufacturers. One of these, the Herman Miller Furniture Company in Zeeland, is known around the world for its long history of producing high quality modern furniture—but the Herman Miller name was not always synonymous with “modern.”

A young man named Dirk Jan (D.J.) De Pree began working as a clerk at the Zeeland-based Michigan Star Furniture Company in 1909, after graduating from high school. It was a small company and De Pree excelled, partly due to his appetite for reading books about business, accounting, and efficiency. Just a decade after starting with the company, he was promoted to president. In 1923, De Pree convinced his father-in-law, Herman Miller, to go in with him to purchase the majority of the company’s shares. The furniture company was renamed the Herman Miller Furniture Company in honor of De Pree’s father-in-law’s contribution, although Miller was never involved in its operation. Renamed, rebranded, and under new ownership, D.J. De Pree pushed a new culture of quality and good design that, he hoped, would help the company stand out amongst a competitive and crowded West Michigan furniture industry.

Dressing Table, ca. 1933 (Object ID: 89.177.112), Image copyright: Herman Miller, Inc.

At the time, many West Michigan furniture companies were producing stylistically similar pieces that were essentially reproductions of historic forms, especially Colonial and European Revivals. Most of the manufacturers “designed” furniture by copying from books or authentic vintage furniture found in museums. The best designers were known to be the most faithful copyists. The Herman Miller Furniture Company manufactured primarily reproduction furniture until the early 1930s. Their furniture lines were typically very ornate and sold in large suites—and following in the footsteps of other West Michigan companies, Herman Miller released new lines with each quarterly furniture market, despite the undue pressure this placed upon them.

As the Great Depression crippled industry across America in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Herman Miller Furniture Company struggled to survive. With bankruptcy on the horizon, D.J. De Pree reflected on the shortcomings of the furniture industry and issues within the company. A devoutly religious man, he also prayed. Whether by divine intervention or regular old coincidence, Gilbert Rohde—a young designer that would leave an indelible mark on the Herman Miller Furniture Company—walked into the company’s Grand Rapids showroom in July of 1930, bringing with him the message of Modernism.

The Herman Miller Furniture Company, Makers of Fine Furniture, Zeeland, Michigan, 1933 (Left: THF64292, Right: THF64290). Herman Miller continued to produce historic revival furniture, like the above Chippendale bedroom suite, even while embracing the more modern Gilbert Rohde lines, like the above No. 3321 Dining Room Group.

Born in New York City to German immigrants in 1894, Gilbert Rohde (born Gustav Rohde) showed aptitude for drawing at a young age—he claimed to have drawn an identifiable horse by the age of two-years-old! He was admitted to Stuyvesant High School in 1909, which was reserved for gifted young men. There, he designed covers for the school’s literary magazine, won drawing contents, and began to experiment with furniture design. While he had aspirations (and demonstrated aptitude) to become an architect, he began working as an illustrator and later, a commercial artist. He was successful in this venture for years and learned invaluable lessons about advertising and marketing which would help him—and his future clients—tremendously in the years to come. With determination to become a furniture designer, in 1927 Rohde departed on a months-long European tour of sites associated with the modern design movement. Among his stops, he visited the Bauhaus design school in Germany and the Parisian design studios that featured the modernist ideas exhibited in the breakthrough Exposition International des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes of 1925. Returning to the United States months later, he began designing furniture with a clear European modern influence and soon began to focus on designing mass-produced furniture for industry, namely for the Heywood-Wakefield Company of Massachusetts.

Dresser, 1933-1937 (THF156178). An early example of Rohde-designed furniture manufactured by Herman Miller, this dresser was designed for the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair’s “Design for Living Home.” The house and its furniture garnered broad public acclaim, benefitting the budding Rohde and Herman Miller partnership.

By 1930, Rohde was looking for more clients. He visited the Herman Miller showroom in Grand Rapids, Michigan—at the end of a long day of denials by other manufacturers—and met D.J. De Pree. Rohde argued that modern furniture was the future and told him, “I know how people live and I know how they are going to live.” This confidence, despite few years of actual furniture design, convinced De Pree to give Rohde a chance at designing a line for Herman Miller. Further, Rohde was willing to work on a royalty arrangement with a small consultation fee instead of all cash up front. In combination with Herman Miller’s already-precarious financial situation, these factors helped to offset some of the risk in producing this forward-thinking furniture. Herman Miller began selling Rohde’s first design, an unadorned, modern bedroom suite in 1932, but still played it safe by continuing to sell historic revival lines alongside Rohde’s modern furniture. As design historian Ralph Caplan notes, in those early years, Herman Miller was “like a company unsure of what it wanted to be when it grew up.” But Rohde’s furniture sold. By the early 1940s, Rohde’s modern lines made up the vast majority of Herman Miller’s output.

Left: Coffee Table, 1940-1942 (THF35998), Right: Rohde Sideboard, 1941-1942 (THF83268). Gilbert Rohde admired the Surrealist Art Movement. In his early 1940s Paldao Group, the forms and materials pay homage to the work of the Surrealists—and were the first biomorphic forms used in furniture manufactured in the United States.

Tragically, Rohde’s tenure at Herman Miller was cut short by his untimely death at the age of 50 in 1944, but his impact is lasting. Rohde’s emphasis on simplicity and functionality of design meant the materials and the manufacturing had to be of the highest quality—this honesty of design and emphasis on quality appealed to De Pree’s Christian values. It remains a hallmark of Herman Miller’s furniture to this day and undoubtedly contributed to the longevity of Rohde’s furniture sales. Sales of Rohde’s furniture did not slow the season after it was introduced, like many of the historic reproductions. The Laurel Line, Rohde’s first coordinated living, dining, and sleeping group, remained in production almost his entire tenure with Herman Miller. D.J. De Pree recounted that his lines often sold for 5-10 years instead of the 1-3 that was typical of the historic reproduction styles. Rohde’s design work for Herman Miller extended far beyond furniture and into advertising, catalogues, and showrooms, and he advised on the manufacture of his furniture too. This expansion of the designer’s role and the creative freedom allowed by D.J. De Pree came to define Herman Miller’s relationship with designers and then the company itself.

Rohde Modular Desk, 1934-1941 (THF159907). This Laurel Group desk was part of one of Rohde’s early—and most successful—lines for Herman Miller. It was part of a coordinated modular line, which meant that new pieces would be added regularly over years. This was in opposition to the new lines for each quarterly furniture market approach that D.J. De Pree counted as an “evil” of the furniture industry.

Cover and interior page from Catalog for Herman Miller Furniture, "20th Century Modern Furniture Designed by Gilbert Rohde," 1934 (left: THF229409, right: THF229411). Gilbert Rohde expanded the role of the designer during his tenure at Herman Miller. In this 1934 catalogue, he was educator as well as designer, explaining to the consumer that “Every age has had its modern furniture…When Queen Elizabeth furnished her castles, she did not order her craftsmen to imitate an Egyptian temple…”

Gilbert Rohde and D.J. De Pree transformed the Herman Miller Furniture Company—from one manufacturing reproductions at the brink of bankruptcy, to one revolutionizing the world of modern furniture. George Nelson, Charles and Ray Eames, Isamu Noguchi, Alexander Girard and countless others were able to make incredible leaps in the name of modernism, largely due to the culture and partnership developed by Gilbert Rohde and D.J. De Pree. In George Nelson’s words, “we really stood on Rohde’s shoulders.”

Katherine White is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

20th century, Michigan, Herman Miller, furnishings, design, by Katherine White

The Henry Ford’s Model i learning framework identifies collaboration as a key habit of an innovator. When considering inspirational collaborators from our collection, Charles and Ray Eames immediately came to mind. So, as part of The Henry Ford’s Twitter Curator Chat series, I spent the afternoon of June 18th sharing how collaboration played an important role in Charles and Ray Eames’ design practice. Below are some of the highlights I shared.

First things first, Charles and Ray Eames were a husband-and-wife design duo—not brothers or cousins, as some think! Although Charles often received the lion’s share of credit, Charles and Ray were truly equal partners and co-designers. Charles explains, "whatever I can do, she can do better... She is equally responsible with me for everything that goes on here."

THF252258 / Advertising Poster for the Exhibit, "Connections: The Work of Charles and Ray Eames," 1976

So when you see early advertisements that don’t mention Ray Eames as designer alongside Charles, know that she was equally responsible for the work. Here’s one such advertisement from 1947.

THF266928 / Herman Miller Advertisement, June 30, 1947, "Now Available! The Charles Eames Collection...."

And here’s another from 1952. I could go on, but I think you get the point!

THF66372 / Wood, Plastic, Wire Chairs & Tables Designed by Charles Eames, circa 1952

For more on Ray’s background and vital role in the Eames Office, check out this article from the New York Times, as part of their recently-debuted “Mrs. Files” series.

Charles and Ray Eames were experimenting with plywood when America entered World War II. A friend from the Army Medical Corps thought their molded plywood concept could be useful for the war effort—specifically for a new splint for broken limbs. Metal splints then in use were heavy and inflexible. Charles and Ray created a molded plywood version and sent a prototype to the U.S. Navy. They worked together and created a workable—and beautiful—solution for the military.

THF65726 / Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint, circa 1943

Out of these molded plywood experiments and products came the iconic chairs we know and love, like this lounge chair.

THF16299 / Molded Plywood Lounge Chair, 1942-1962

But Charles and Ray Eames wanted to make an affordable, complex-curved chair out of a single shell. The molded plywood checked some of their boxes, but the seat was not a single piece—not a single shell. They turned to other materials.

Around 1949, Charles brought a mock-up of a chair to John Wills, a boat builder and fiberglass fabricator, who created two identical prototypes. This is one of those prototypes—it lingered in Will's workshop, used for over four decades as a utility stool. The other became the basis for the Eames’ single-shell fiberglass chair.

THF134574 / Prototype Eames Fiberglass Chair, circa 1949

Charles and Ray recognized when their expertise fell short and found people in other fields to help them solve design problems. Their single-shell fiberglass chairs became a rounding success. Have you ever sat in one of them?

THF126897 / Advertising Postcard, "Herman Miller Furniture is Often Shortstopped on Its Way to the Destination...," 1955-1960

If you’ve been to the museum in the past few years, you’ve surely spent some time in another Eames project, the Mathematica: A World of Numbers…and Beyond exhibit. This too was a project full of collaborative spirit!

While those of us not mathematically inclined might have a hard time finding math fun, mathematicians truly think their craft is fun. Charles and Ray worked with these mathematicians to develop an interactive math exhibit that is playful.

THF169792 / Quotation Sign from Mathematica: A World of Numbers and Beyond Exhibition, 1960-1961

Charles Eames said of science and play, “When we go from one extreme to another, play or playthings can form a transition or sort of decompression chamber – you need it to change intellectual levels without getting a stomachache."

THF169740 / "Multiplication Cube" from Mathematica: A World of Numbers and Beyond Exhibition, 1960-1961

Charles and Ray Eames sought out expertise in others and worked together, understanding that everyone can bring something valuable to the table. This collaborative spirit allowed them to design deep and wide—solving in-depth problems across a multitude of fields.

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. For a deeper dive into this story, please check out her long-form article, “What If Collaboration is Design?”

Eames, women's history, Model i, Herman Miller, furnishings, design, by Katherine White, #THFCuratorChat

A More Colorful World

This vibrant dress was likely dyed using an early aniline purple dye. Dress, 1863-1870 (THF182481)

In 1856, British chemistry student William Henry Perkin made a groundbreaking discovery. Perkin’s professor, August Wilhelm von Hofmann, encouraged his students to solve real-world problems. High on the list for Hofmann (and chemists all over the world) was the need to create a synthetic version of quinine. The only effective treatment for the life-threatening malaria disease, quinine could only be found in the bark of the rare Cinchona tree. Just a teenager at the time, Perkin decided to tackle this problem in a makeshift laboratory in his parents’ attic while on Easter holiday. Perkin experimented with coal tar—a coal byproduct in which Professor Hofmann saw promise—and made his discovery. No, not the discovery of a synthetic quinine, but something altogether different and extraordinarily significant nonetheless.

Wells, Richardson & Company "Leamon's Genuine Aniline Dyes: Purple," 1873-1880 (THF170208)

Perkin’s coal tar experiments resulted in a dark-colored sludge which dyed cloth a vibrant purple color. The purple dye was colorfast too (meaning it did not fade easily). He had discovered aniline purple—also known as mauveine or Perkin’s mauve—the first synthetic dye. Though this was not the medical miracle he had initially sought, he immediately understood the vast significance and marketability of a colorfast, synthetic dye.

Prior to Perkin’s discovery, natural dyes were used to color fabrics and inks and were derived primarily from plants, invertebrates, and minerals. Extracting natural dyes was time consuming and certain colors were rare. For example, arguably the most precious natural dye also happened to be a vibrant purple, called Tyrian Purple. This dye was found in the glands of several species of predatory sea snails. Each snail contained just a small amount of dye, so it took tens of thousands of sea snails to dye a garment a deep purple. Tyrian purple was so expensive that the very wealthy could afford to wear it. It’s no wonder purple was seen as the color of royalty!

Fabric Dye Swatch Book, "Kalle & Co. Manufacturers of Aniline Colors," circa 1900 (THF286612 and THF286614)

William Henry Perkin turned out to be multi-talented, finding success both as a chemist and as an entrepreneur. By 1857, with the help of his family, he began commercially manufacturing his aniline dye near London. He first produced purple, but other colors soon followed. The water in the nearby Grand Union Canal was said to have turned a different color each week depending on what dyes were being made. In 1862, Queen Victoria attended the Great London Exposition in a gown dyed with Perkin’s mauve and the color took off. Newspapers even reported a “mauve mania” in the 1860s! These new synthetic dyes were affordable too and other manufacturers around the world began to produce them. By 1880, companies like The Diamond Dye Company of Vermont sold many colors of dye—from magenta to gold or even “drab”—for just 10 cents apiece.

Trade Card for Diamond Dyes Company, 1880-1890 (THF214453 and THF214454)

Perkin’s discovery spawned an entirely new industry that transformed the world’s access to color. It is fitting that the very first synthetic dye created was purple—the color of Roman emperors and royalty could now be purchased for pennies. Louis Pasteur’s famous quote, “Chance favors the prepared mind,” characterizes Perkin’s serendipitous discovery well. His accidental discovery was far from simple luck – others may have dismissed it as a failed experiment. Instead, Perkin recognized the potential in his mistake and seized the opportunity to bring color to the masses.

Katherine White is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Europe, 19th century, 1850s, fashion, entrepreneurship, by Katherine White, #THFCuratorChat

Look for the Helpers

Red Cross Volunteer Nurse's Aides, May 1942. THF289753

In uncertain times, it can be useful to stop and reflect on the ways in which others have overcome or responded to challenges. The passage of time can be a cushion, allowing us to use the lens of history to reach back and remember that remarkable creativity, kindness and courage have often pushed through fear in times of uncertainty.

Opportunities for compassion and ingenuity abound, even for those of us not on the front lines—be it the front lines of a hospital, of the food supply chain, or of municipal services. Perhaps your opportunity might be painting rocks to hide in your neighborhood to make a neighbor smile or sewing a mask for a health care worker. It could be putting groceries in your little library as well as books. Maybe it is inventing a vaccine or building new ventilators.

Let’s absolutely “look for the helpers,” as Mister Rogers said, but let’s also look for the makers, the inventors, the doers, the innovators—past and present—and be inspired to become more like them too. Encouragement from sidewalk chalk and painted rocks in a Michigan neighborhood.

Encouragement from sidewalk chalk and painted rocks in a Michigan neighborhood.

THF Resources

The Henry Ford's Blog: Uncovering Medical Innovations in the Collection

New surgical techniques and motorized medical care are just a few of the ingenious responses to medical demands featured in this blog post.

The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation: UpSee Walking Device

When Debby Elnatan’s son was unable to walk due to cerebral palsy, she invented a walking device to help him and other children with the disorder. In this clip from The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation, she explains, “I believe there is no such thing as special needs, that we all have the same needs. What’s special are the solutions.”

The Henry Ford's Blog: A Technological Assist

Today, assistive devices and technology are increasingly common, but this wasn’t always the case. Empathetic design and inventiveness were required to create devices which allowed people like Shari, introduced in this blog post, to wake up on time, watch television, or chat with a friend.

Katherine White is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

COVID 19 impact, accessibility, healthcare, by Katherine White

The Exuberant Artistry of Mary Blair

Mary Blair was the artist for this hand-pulled silkscreen print, used in a guest room at Disney’s Contemporary Resort, Walt Disney World, 1973 to early 1990s. THF181161

When Disney’s Contemporary Resort opened at Walt Disney World in 1971—coinciding with the opening of Magic Kingdom—guests almost immediately complained about their rooms. The rooms seemed cold and hard. They lacked personality. Guests couldn’t even figure out how to operate the new-fangled recessed lighting. So, within two years, the rooms were refurbished with new textiles, fabrics, traditional lamps, and high-quality prints of Mary Blair’s original design. These prints were adapted from the individual scenes of a massive tile mural that she had created for the Contemporary Resort’s central atrium. The hand-pulled silk-screened prints, framed and hung on the walls over the beds, brought much-needed warmth, color, and a sense of playful exuberance to the rooms. More importantly—but probably unbeknownst to most guests—they reinforced Mary Blair’s deep, longstanding connection to Disney parks, attractions, and films that ultimately dated back to a personal friendship with Walt Disney himself.

Mary Blair was born Mary Browne Robinson in 1911 in rural Oklahoma. She developed a love of art early in her childhood and went on to major in fine arts at San Jose State College. She won a prestigious scholarship to the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles (which later became the California Institute of the Arts) and studied under the tutelage of Chouinard’s director of illustration, Pruett Carter. Carter was one of the era’s most accomplished magazine illustrators and stressed the importance of human drama, empathy, and theatre in illustration. Mary later recalled that he was her greatest influence.

By the late 1930s, Mary and her husband, fellow artist Lee Blair, were unable to survive off the sales of their fine art and began to work in Los Angeles’s animation industry. In 1941, both were working at Disney and had the opportunity to travel with Walt Disney and a group of Disney Studio artists to South America to paint as part of a government-sponsored goodwill trip. While on this trip, Mary grew into her own as an artist and found the bold and colorful style for which she would be known.

Mary Blair became one of Walt Disney’s favored artists, appreciated for her vibrant and imaginative style. She recalled, “Walt said that I knew about colors he had never heard of.” In her career at Disney, she created concept art and color styling for many films, including Dumbo (1941), Saludos Amigos (1942), Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951), and Peter Pan (1953). She left Disney after her work on Peter Pan to pursue freelance commercial illustration, but returned when Walt Disney specifically requested her help to create the “it’s a small world” attraction for the 1964-5 New York World’s Fair (later brought back to Disneyland and also recreated in Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World).

Before Walt Disney passed away in 1966, he commissioned Mary to produce multiple large-scale murals, including the one for the interior of the Contemporary Resort at Walt Disney World in Florida. The mural, completed in 1971, was her last work with Disney. Entitled “The Pueblo Village,” it featured 18,000 hand-painted, fire-glazed, one-foot-square ceramic tiles celebrating Southwest American Indian culture, prehistoric rock pictographs, and the Grand Canyon. (Because Mary’s depictions of Native Americans admittedly lack attention to the serious study of indigenous people in that region, they might be criticized as racial stereotyping).

When the guest rooms at the Contemporary Resort were renovated again in the early 1990s, the high-quality prints were removed. But the massive tile mural stoically remains at the center of the Resort’s ten-story atrium—a reminder of Mary Blair’s exuberant artistry and her many contributions to Disney parks and films.

For more on Mary Blair’s contributions, along with the previously unrecognized contributions of numerous other female artists who worked on Disney films, see the book The Queens of Animation: The Untold Story of the Women Who Transformed the World of Disney and Made Cinematic History, by Nathalia Holt (2019).

This blog post was a collaborative effort by Donna Braden, Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford, and Katherine White, Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Indigenous peoples, Florida, 20th century, 1970s, 1960s, women's history, Disney, design, by Katherine White, by Donna R. Braden, art

The Tale of the Nauga’s Hide

Naugahyde Advertisement in Life Magazine, October-December 1967. This image is not an original photograph and is a combination of two images created for illustrative proposes.

The Nauga, a colorful, horned, happy-looking creature native to the island of Sumatra, was once hunted to near-extinction. They were hunted for sport, but more often for their smooth and durable leather-like hide – Naugahyde, as it’s generally known. However, hunting a Nauga for its hide is quite unnecessary -- they painlessly shed their hide at least once each year for use in furniture, clothing, and more.

Wait a minute.

You’ve never heard of the Nauga?

All right, you’ve got me. The Nauga is a fictional creature. It was an advertising gimmick created to help Uniroyal Engineered Products promote their soft vinyl-coated fabric that feels like leather but is more durable. The product, Naugahyde, was used primarily as upholstery in the furniture industry, but also was used for clothing, shoes, accessories and other home goods. Its success spawned many imitators. In the mid-1960s, Uniroyal hired legendary ad-man George Lois and designer Kurt Weihs to craft an advertising campaign to differentiate their product from the competition. And what did Lois and Weihs create? The Nauga.

A humorous ad campaign featured the Nauga engaged with the world – as the life of the party, as a child’s play companion, adorned in splattered paint from a craft went awry, even as a vacationer readying for travel with golf clubs in hand. These advertisements emphasized the suitability of Naugahyde upholstery for all areas of life, claiming it could be indistinguishable from other fabrics like leather, tweed, or silk -- but “last about ten times as long.” An image of the Nauga found its way onto hang-tags that accompanied all genuine Naugahyde products. Many of the ad campaigns ended with this directive: “If you can’t find the Nauga, find another store.”

Naugahyde advertisement in Life Magazine, July-September 1967.

The advertising worked – at least in that it caused excitement over the mysterious Nauga creature. Allegedly, some people even believed Naugas were real creatures and became concerned about inhumane treatment as the use of Naugahyde boomed in the late 1960s. A New York comic, Al Rosenberg, invented a fictional character named Earl C. Watkins who spearheaded the “Save the Nauga” project to protect the species from extinction, adding that a “herd of Naugas is often mistaken for a roomful of furniture.'' The Nauga even made an appearance on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. Nauga dolls, like this one in The Henry Ford’s collection, were also produced to promote the brand. In fact, if you visit the Naugahyde website today, you can still “Adopt a Nauga,” which, according to the company’s webpage, are bred on a ranch outside Uniroyal’s headquarters in Stoughton, Wisconsin.

Uniroyal "Nauga" Toy, 1955-1975

It isn’t unusual for companies to go to great lengths to endear a product to the public. These efforts have often yielded highly creative and memorable results, like Oscar Mayer’s Wienermobile, the Heinz pickle charms and pins, or the Pets.com Sock Puppet, to name a few. While the Nauga creature has faded nearly into obscurity, the leather-like product it represents lives on…perhaps even as the upholstery of the chair you’re currently sitting on.

Katherine White, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford, recently adopted a Nauga doll of her very own.

toys and games, by Katherine White, advertising, furnishings

The Search for Home

Detroit Reacts to the Great Migration: Before the first World War, a majority of Detroit's African American population lived on the East Side and shared the area, known as Black Bottom, with white immigrant populations. At this time, relatively few African Americans, just 1.2% of the total population, called Detroit home. By 1930, the city’s African American population had grown by over 1,991%. The white immigrant population began to vacate the Black Bottom area and were quickly replaced with the growing population of African Americans attracted to the north by the promise of employment in Detroit’s booming auto industry and an escape from the rampant oppression of the south. As the African American population in Detroit increased, racial residential boundaries began to form, due in part to the stress on housing stock, as well as to outright discrimination in institutions such as employment and real estate.

Photographic print - "Newspaper Article, "Gold Rush is Started by Ford's $5 Offer," January 7, 1914" - Ford Motor Company

The automobile industry and Henry Ford’s highly-publicized $5-a-day helped to draw people in great numbers to the Detroit area. However, for African American workers, reality often differed from their hopes and expectations in the north. While many of the automotive manufacturers did hire African Americans, it was almost always for the lowest paying jobs, such as in the janitorial department or the foundry. Ford Motor Company led the automotive industry in its hiring of African American workers by 1919. The company paid African American workers the same rate as their white counterparts and hired for a variety of positions, including skilled labor. Across the board, however, African American workers made less money than their white counterparts, and consequently, had less income for quality housing.

Photographic print - "Pickling Metal Crankcases and Other Parts to Remove Surface Impurities, Ford Rouge Plant, 1936" - Ford Motor Company Photographic Department

Discriminatory real estate practices played a significant role in the housing issues which plagued Detroit. Racially restrictive covenants, which legally ensured the sale of property to only white buyers, became increasingly common in Detroit. Even if a restrictive covenant was not in place, the Detroit Real Estate Board warned area realtors “not to sell to Negroes in a 100 percent white area,” thereby enforcing and perpetuating Detroit’s racial geography. Further, the practice of “redlining,” or the racial categorization of areas by their perceived financial risk in home insurance and mortgage lending, effectively shut out black homebuyers from the market. The practice extended to the lending of new mortgages, but also to home loans, leading to the inability to complete home repairs and, eventually, an abundance of blighted homes in black neighborhoods. In addition, real estate agents erroneously reported to white homeowners that the presence of black families in their neighborhoods would lower their property values. White homeowners, even those without ingrained prejudices against African Americans, certainly did not want their property values to lower, so rallied against any attempt by an African American homebuyer purchasing in their neighborhoods. The infamous story of African American Physician Dr. Ossian Sweet exemplifies the discrimination and mob violence experienced by those who attempted to move into white neighborhoods.

Discrimination in the workplace meant that African Americans, as a whole, made significantly less money than their white counterparts. Redlining practices forced them into racially-segregated neighborhoods and cemented their inability to access loans for mortgages or home repairs. Yet, the promise of the north continued to draw African Americans to Detroit. Without access to capital, increasingly-crowded neighborhoods became increasingly-deteriorated. At each turn, discriminatory systems excluded an entire population from quality housing. From these conditions, Charles H. Lawrence and his family departed Detroit in search of quality housing and a better life. He became the first African American to settle in Inkster, Michigan, and hundreds soon followed.

African Americans Settle in Inkster

The City of Inkster, also located in Wayne County, is approximately fourteen miles from downtown Detroit. Detroit Urban League President John Dancy fielded many housing inquiries from frustrated African American migrants to Detroit in the post-World War I period and beyond. Unable to locate sufficient housing in the City of Detroit, Dancy broadened his search outside the City with hopes that more rural areas would not have the same restrictive covenants and that lesser demand would persuade landowners to sell to African American buyers. In 1920, Dancy succeeded when he found amenable property owners in possession of 140 acres in rural Inkster. Although Inkster’s first African American residents’ settlement in Inkster preceded Dancy’s discovery, the 140 acres of available land enabled and impelled hundreds more African American families to move from Detroit to Inkster, despite the lack of a local government or basic public amenities like streetlights or sewer lines.

Clipping (Information artifact) - ""Henry Ford on Unemployment," 1932" - Detroit Free Press (Firm)

A Community Becomes a Project

Henry Ford was vocal about his disdain for institutionalized philanthropy. He wrote an entire chapter, entitled “Why Charity?” in an autobiography, and explained, “philanthropy, no matter how noble its motive, does not make for self-reliance…A philanthropy that spends its time and money in helping the world to do more for itself is far better than the sort which merely gives and thus encourages idleness.” Henry Ford’s brand of philanthropy was characterized by helping people help themselves. During the Great Depression, Henry Ford was called upon by the City of Detroit to provide aid because the City’s welfare offices were overwhelmed. Their argument, aside from civic responsibility, was that the City was not receiving taxes from Ford Motor Company (FMC’s factories were located outside Detroit) yet as many as “36 percent of the families receiving care from the City of Detroit were former Ford employees” in 1931. The public goodwill that Ford’s $5 a day policy brought was quickly dissipating. In 1931, Ford agreed to two philanthropic ventures; he provided a low-interest, short-term $5 million loan to the City of Detroit and essentially took the then-Village of Inkster under the Ford Motor Company’s auspices.

Photographic print - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

Photographic print - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

Photographic print - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

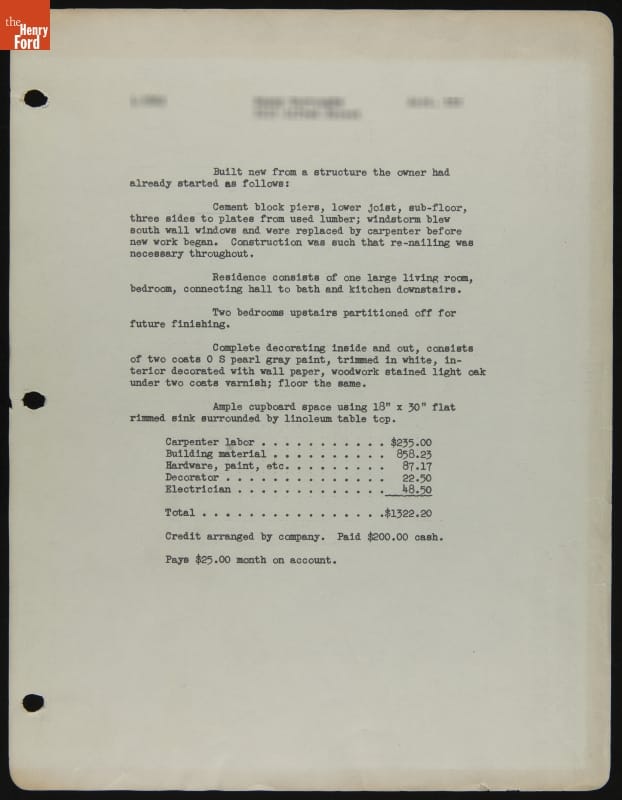

Report - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

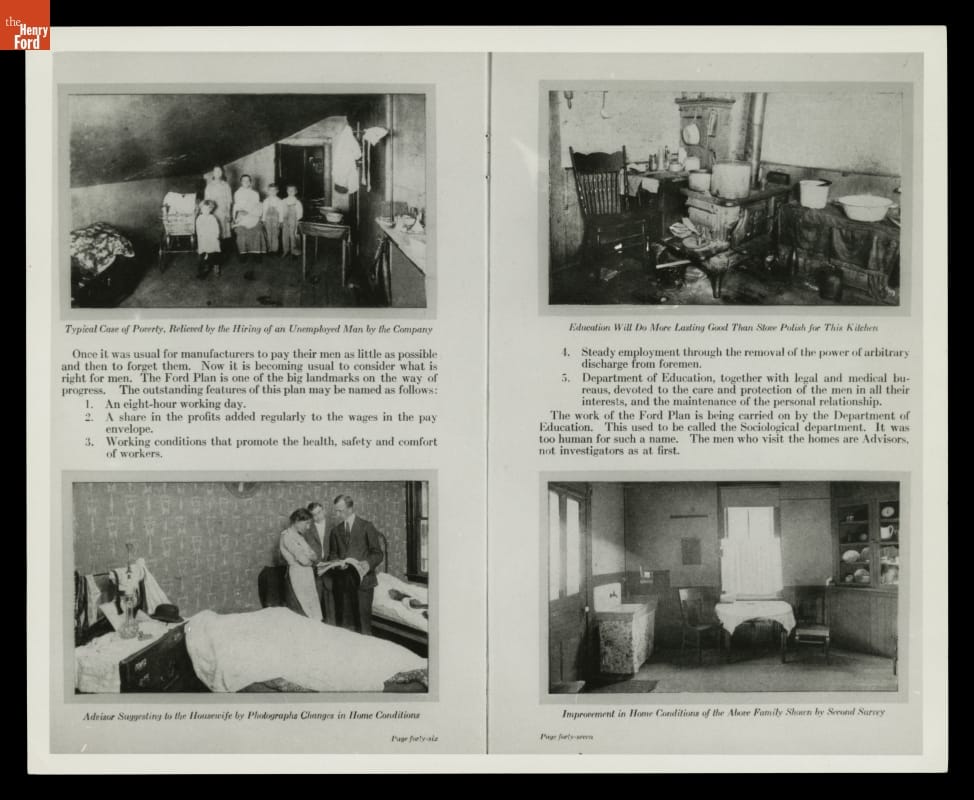

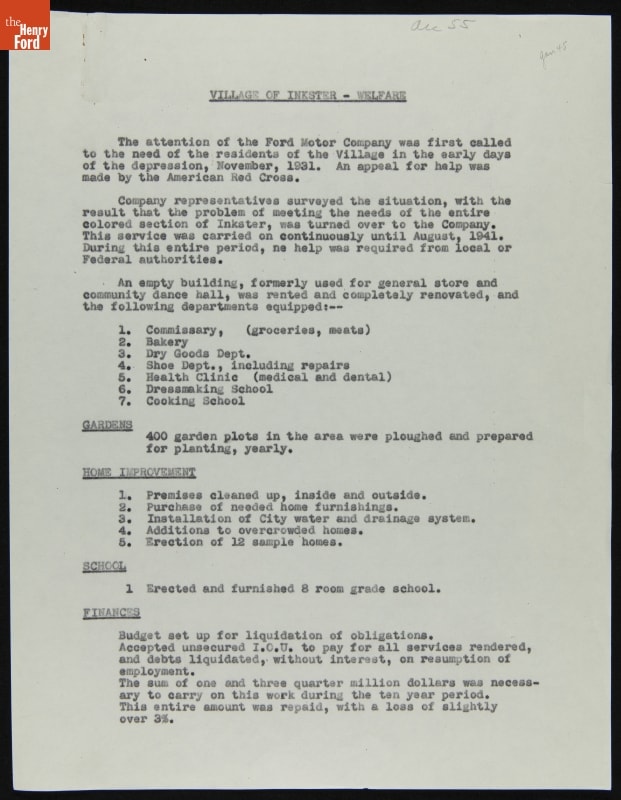

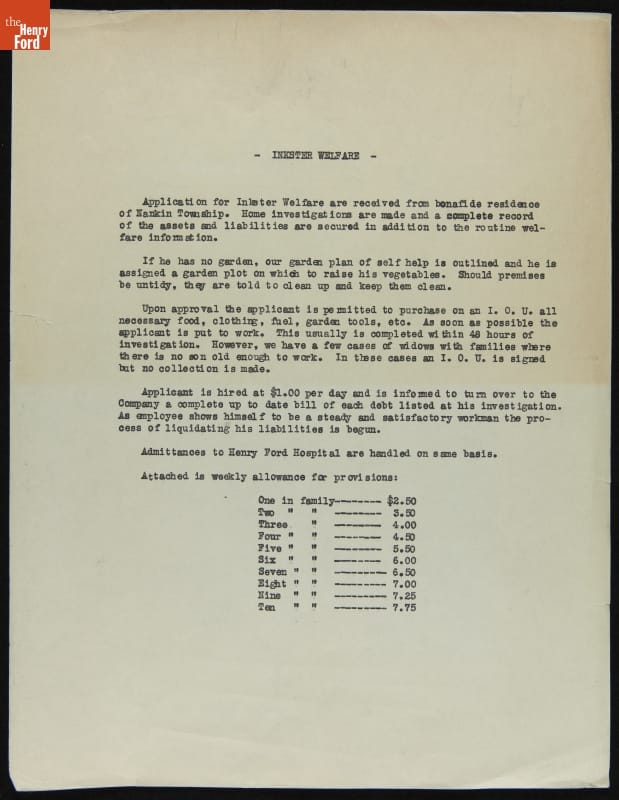

By 1931, a few years into the Great Depression’s hardships, the residents of Inkster were struggling. Unemployment and debt were high, public services had been cut, and many residences remained partially-completed, as the Great Depression halted progress in the young village. Controversially, Henry Ford placed FMC’s Sociological Department in charge of what became known as the Inkster Project. The Sociological Department was created in 1914 in order to manage the diverse workforce and ensure employee adherence to the company’s strict standards, which were paternalistic in nature and often crossed the home life-work life boundary. In Inkster, the Sociological Department immediately began implementing programs to comprehensively rehabilitate the village. A commissary, which sold high-quality, low-cost food and essential home goods, was established. Coal was distributed to those who needed it to heat their homes. Debtors were paid off, and a medical clinic and school were constructed. Homes deemed insufficient were rehabilitated. The inability to pay for these services was irrelevant; a type of “I.O.U,” repayable through Ford-provided work and wages, was enough to access all life’s necessities.

Photographic print - "Checking on Ford Employees Home Conditions, Views from "Factory Facts From Ford," 1917"

The Legacy of the Inkster Project

Although the Inkster Project was generally highly-regarded at the time, the FMC Sociological Department’s role was often overreaching. When agreeing to Ford’s aid, an Inkster resident was also agreeing to running their household as preferred by Henry Ford. Although his funds undoubtedly helped Inkster during the Great Depression, Ford’s motives were not entirely altruistic. Besides the much-needed public relations boost he received from the Inkster Project, he also was able to assert his influence and ideals on a community that largely had no choice but to accept his aid -- with all strings attached.

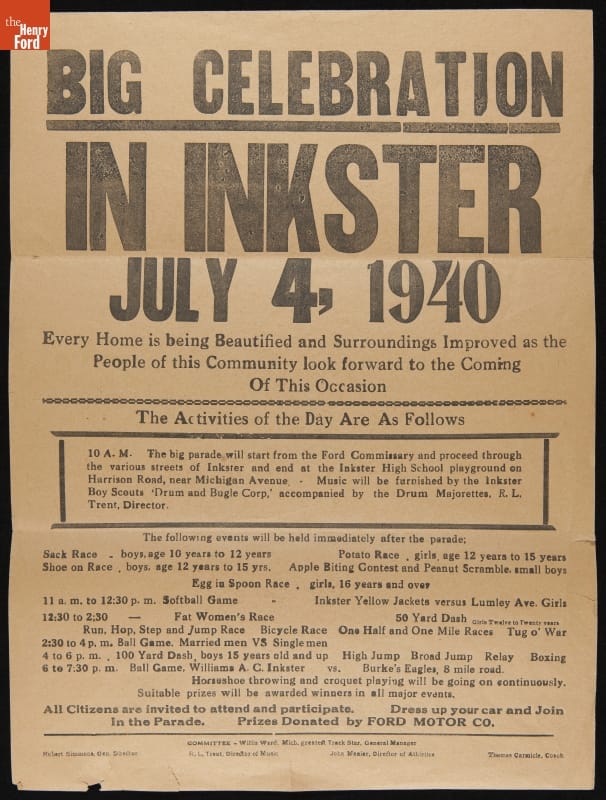

Broadside (Notice) - "Big Celebration in Inkster," July 4, 1940"

The Inkster Project’s legacy is complicated; many historians criticize Henry Ford’s paternalistic nature and the perhaps forceful imposition of his will onto the desperate, but others, including former residents of Inkster, praise Henry Ford for his aid. In her reminiscences, Georgia Ruth McKay explains that Inkster became a “jungle village changed into a city” during this period and that, “without his [Henry Ford’s] help, many would not have survived.” The Inkster Project was slowly phased out, but continued to operate in Inkster until 1941 when all programs were withdrawn.

Progress report - "Village of Inkster Welfare Report, 1931-1941" - Ford Motor Company

Report - "Village of Inkster Welfare Provision Report, circa 1936" - Ford Motor Company

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. In writing this piece, she appreciated the research and writings of Beth Tompkins Bates’ “The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford”, Thomas J. Sugrue’s “The Origins of the Urban Crisis; Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit,”, and Howard O’Dell Lindsey’s dissertation, “Fields to Fords, Feds to Franchise: African American Empowerment in Inkster, Michigan.”

20th century, Michigan, labor relations, home life, Henry Ford, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, Detroit, by Katherine White, African American history

The 1929 Women’s “Powder Puff” Air Derby

“The glory of soaring above God’s Earth and the satisfaction of taking the machine up and bringing it back to the ground safely, through my own skill and judgment, has melted away the boundaries of my life. Racing opens my door to the world. Don’t cut me off from the adventure men have been hoarding for themselves in the guise of protecting me from danger.” – unnamed female aviator, 1929

Several of the women aviators competing in the 1929 Air Derby gathered for this photograph at Parks Airport in Illinois. Included, from left-to-right, are Mary Von Mach, Jessie Miller, Gladys O’Donnell, Thea Rasche, Phoebe Omlie, Louise Thaden, Amelia Earhart, Blanche Noyes, Ruth Elder, and Vera Walker. THF256262

The 1929 Women’s “Powder Puff” Air Derby was the first air race in which women aviators were allowed to participate, despite air races occurring internationally and nationally since 1909. By 1929, 117 women held pilot’s licenses in the United States and were breaking records, including some set by men, left and right. Twenty of these aviators arrived at Clover Field in Santa Monica ready to compete, but perhaps the greater motivation was to show the world how truly capable women aviators were.

The derby, from Santa Monica, California, to Cleveland, Ohio, was to be completed over nine days with the total time in flight recorded each day. The aviator with the shortest flight time overall, for both the DW (heavy aircraft) and CW (light aircraft) classes, would win the top prize. In order to qualify to compete, the aviators, like their male counterparts in the National Air Races, were required to have completed over 100 logged hours in flight. Several of the twenty aviators did not actually meet this qualification but flew anyway. Unlike their male counterparts, however, there were restrictions placed on the women’s aircraft engine strength. One of the aviators, Opal Kunz, had her newly-purchased 300 horsepower Travel Air airplane deemed “too fast for a woman” and was forced to rent a 200 horsepower plane for use in the derby.

The nine-day derby saw multiple mishaps. Both Florence “Pancho” Barnes and Ruth Nichols crashed their planes but managed to escape unscathed. Phoebe Omlie accidentally landed in a field where the local Sheriff nearly arrested her for alleged drug smuggling, while numerous other aviators discovered suspected sabotage efforts to their aircraft. Ruth Elder, lost on the leg to Phoenix and needing directions, accidentally landed in a field of grazing bulls, causing her to panic that the red color of her airplane would incite anger. The farmer’s wife relayed her location and Elder quickly resumed flight without damages. Tragically, on the second day of the race, Marvel Crosson perished when she crashed in the Arizona desert. Despite calls to suspend the race after Crosson’s death, the remaining women decided that finishing the race would best honor their fallen friend.

On the final day, August 26, 1929, fifteen of the original twenty women crossed the finish line in Cleveland, Ohio. Louise Thaden won the DW class and Phoebe Omlie won the CW class. As Thaden was lauded for her first-place finish, she addressed the crowd, “The sunburn derby is over, and I happened to come in first place. I’m sorry we all couldn’t come in first, because they all deserve it as much as I.”

The Henry Ford recently added over 200 artifacts related to women aviators to the Digital Collections. Of the women aviators who competed in the 1929 Air Derby, the collection includes archival materials for five of them; Louise Thaden, Amelia Earhart, Ruth Elder, Mary Von Mach, and Ruth Nichols. Numerous other significant early female aviators that did not participate in the 1929 Air Derby are also represented in the collection.

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.Additional Readings:

- Modernizing the Mail

- 1939 Douglas DC-3 Airplane

- Just Added to Our Digital Collections: Wright Brothers Images

- Morgan Gies: Driver to the Presidents

Ohio, 1920s, 20th century, California, women's history, racing, by Katherine White, aviators, airplanes

Although medical history is not currently a focus of The Henry Ford’s collections, we do have numerous medical artifacts because they relate in some way to a different area of our collections, such as public life, transportation, buildings and architecture, or design. New Associate Curators of Digital Content, Katherine White and Ryan Jelso, combed through The Henry Ford’s collection looking for artifacts that were medically innovative, either as physical innovations or as representations of innovations in the medical profession. The objects they found were initially acquired for their relation to a different collections area, but they tie closely to the development of today's medical technologies and practices.

A Civil War surgeon used this government-issued Field Operating Kit, initially acquired by The Henry Ford as a public history artifact, at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May of 1863. It contains all the tools needed to perform the most common Civil War medical procedure – amputation.

New Weapons Technology Leads to New Surgical Techniques

In 1849, French military officer Claude-Etienne Minié invented a hollow-based cylindrical bullet, which was more accurate over long distances than its predecessors and more quickly loaded into a rifle barrel due to its slightly smaller size. The minié bullet provided a significant advantage to those on the offensive; however, the bullet was immensely destructive to those on the defensive. Due to its hollow nature, the projectile became misshapen upon impact and its ragged edges caused significantly more internal damage than the solid bullets used previously.

Both the Union and Confederate Armies utilized the minié bullet extensively during the American Civil War. The damages wrought by this particular bullet surely contributed to the war’s astronomical death count, but also contributed to the advancement of amputation surgery. While amputation had been used throughout the ages, Civil War surgeons innovated numerous surgical advancements. Immediate amputation of an injured limb before infection spread to healthy tissue became standard and drastically decreased battlefield mortality rates.

The Henry Ford's broad transportation collection covers the motorization of ambulances during World War I. Take a look at a few archival photographs that document the Model T's role in this important part of ambulance history, here.

The Motorization of Medical Care

The Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries spurred technological innovations that would change how wars were conducted in the decades to come. By the beginning of World War I in the early 20th century, military units had become increasingly motorized, replacing the horses and wagons of past wars. Armies employed mechanized military vehicles like tanks, airplanes and submarines along with new forms of chemical warfare to inflict mass casualties during what became known as "The Great War." With a surge in casualties, quick transportation of the wounded away from the battlefronts to safer hospitals became a life-saving priority. To meet this need, volunteer services and individual armies experimented with and developed motor ambulance corps, eventually making them commonplace.

The torn up roads, heavily shelled areas, and muddy terrain of the war-torn European continent made lighter vehicles preferable. While other makes and models were present, lightweight Ford Model Ts made up a large percentage of the ambulances in service during World War I. The vehicles’ ability to traverse the war environment along with their easy maneuverability made them popular among ambulance drivers. Other advantages of Model T ambulances included their low cost, economical fuel usage, and ease of operation for the average solider or volunteer. The standardization of Model T parts also meant that maintenance for these ambulances could be performed readily, extending each vehicle's service life and allowing medical professionals to tend to the wounded quicker than ever before.

As a part of the historic building collection in Greenfield Village at The Henry Ford, Doc Howard's office serves as an example of the 19th century origins from which modern American medicine would evolve.

A Snapshot of Mid-19th Century Medicine

Representative of a typical early rural doctor's office, this mid-19th century building is where Dr. Alonson Bingley Howard (1823-1883) practiced an eclectic combination of conventional, botanical, and homeopathic medicine. Born in New York, Howard moved to Tekonsha, Michigan, and began his career as a farmer, eventually deciding that he wanted to become a physician. He first attended Cleveland Medical College from 1850-1851, later entering the University of Michigan's School of Medicine, where he took classes from 1851-1852. Although medical school records list him as a non-graduate, Howard moved back to Tekonsha and went on to practice medicine until his death in 1883.

In the 19th century, medical professionals had a limited understanding of illnesses and often relied on bloodletting or other purging methods to "balance" the body and keep diseases at bay. Along with minor surgery, these common practices were available to Dr. Howard as he traveled across his community attending to pregnancies, chronic diseases, tuberculosis, dental problems, and various wounds. To aid him in treating his patients, he relied on the early pharmaceutical medicines that could be found on the market during this period. However, he also kept a laboratory in his office where he could experiment with developing his own medicines through a wide personal stock of plants and minerals.

The Henry Ford obtained this Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint as a design history artifact. It can be found in design museums throughout the world and is included in The Henry Ford Museum’s “Fully Furnished” exhibit.

Experimentation with Plywood Provides Medical Solution

The Museum of Modern Art held a design competition in 1940 entitled Organic Design in Home Furnishings, which aimed to spur development of modern furniture that adequately addressed the era’s changing way of life. Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen, friends and peers at Michigan’s Cranbrook Academy of Art, entered multiple molded plywood chair designs into the competition and won two of the six categories. At the time, molding or bending plywood was still a quite progressive process and molded plywood was not yet commonly used in mass-produced goods for the public. Along with his wife, Ray, Charles Eames continued experimentation with molded plywood after the competition.

America’s entry into World War II brought shortages of many materials, including metal. Splints for broken limbs had historically been produced of metal, although metal splints were not ideal for military use due to their weight and inflexibility. Charles and Ray Eames, perpetual problem-solvers, designed a lightweight, strong, and flexible leg splint produced through their innovative method of molding plywood. The Eames molded leg splint became a highly effective solution for the military as well as a highly sculptural design object.

Represented in The Henry Ford's large American public life collection is the late 19th- and early 20th-century phenomenon of patent medicines, over-the-counter drugs that consumers used to self-medicate.

Consumerism Helps Standardize Early Medicines

In the late 19th century, an increasing body of medical knowledge had begun to revolutionize the practice of medicine. However, a lack of scientific understanding of early medical drugs meant that drugs used in treatment were often inadequate and could even exacerbate illnesses. At a time when disease was still widespread, Americans sought cures for any number of maladies and tried nearly anything to get relief. Entrepreneurs took advantage, using advertising to make claims and promise cures with manufactured patent medicines. Such patent medicines rose to popularity in the last quarter of the 19th century, but the industry was unregulated and manufacturers were secretive about their recipes.

Some of these concoctions contained harmful ingredients or ingredients used in unsafe quantities. Cocaine, alcohol, opium, and heroin were some of the common ingredients that could be found in early patent medicines. These examples, as well as other additives, could result in addiction or even death, prompting national legislation that prohibited misleading health claims and required manufacturers to list their product's contents. In the United States, the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 helped stop the manufacture of drugs and products considered poisonous, adulterated or mislabeled.

Some of the patent medicines in our collection were analyzed in 2013 through a partnership between The Henry Ford's conservation staff and the Chemistry & Biochemistry Department at University of Detroit Mercy. Their findings, as well as more information on patent medicines can be found here in our Digital Collections.

An artifact, especially an innovative artifact, often has multidisciplinary significance. An object that is distinctly medical in nature may be equally as significant, or even more significant, as a public history or design history artifact. The Henry Ford’s collections boast countless significant artifacts with histories that reach across subject matter boundaries, such as this grouping of medically innovative artifacts.

By Katherine White and Ryan Jelso, Associate Curators, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. This post was made possible in part by our partners at Beaumont. Beaumont is a leading high-value health care network focused on extraordinary outcomes through education, innovation and compassion. For the latest health and wellness news, visit beaumont.org/health-wellness.

20th century, 19th century, patent medicines, healthcare, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Eames, Dr. Howard's Office, design, by Ryan Jelso, by Katherine White