Posts Tagged by rachel yerke osgood

"Long Live" and Prosper: Fandom in Pop Culture

Have you ever decked yourself out in head-to-toe colors of your favorite sports team? Discussed theories about your favorite TV show? Celebrated a fictional holiday like Festivus, wished someone “May the Fourth be with you,” or worn pink on Wednesdays? If so, then you’ve participated in fandom.

On May 4th of each year, Star Wars fans celebrate Star Wars Day. Once a grassroots, fan-led celebration, it has been embraced by Lucasfilm and Disney and bled over into the popular consciousness. / THF95553

The idea of fandom — a group of fans of something or someone, particularly enthusiastic ones — can trace its roots back to the literature of the 1800s and early 1900s. In 1894, literary scholar and critic George Saintsbury coined the term “Janeites” to refer to the most intense devotees of the work of Jane Austen. In 1903, after receiving numerous letters from the character’s devoted fanbase (and after 20,000 readers cancelled their subscriptions to The Strand, in which his stories were published), Sir Arthur Conan Doyle brought Sherlock Holmes back to life, eight years after killing the character off in hopes of moving on to other projects. Doyle’s “resurrection” of Sherlock Holmes is perhaps one of the earliest examples of fandom shaping the work that it so adores.

Sherlock Holmes’s popularity has lasted well beyond his own “lifetime.” He has been portrayed in film and television over 250 times, and is often treated as a real historic figure, despite his fictional nature. / THF722711

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, fandom communities began to coalesce around the stories published by Hugo Gernsback in Amazing Stories, the first science fiction magazine. Gernsback published the letters and addresses of fans who sent in mail to the magazine, allowing fans to begin writing to each other, too, meeting up whenever possible. In 1934, Gernsback created the Science Fiction League, a correspondence club for fans of the genre. The Philadelphia Science Fiction Conference was held in 1935, arguably the first of what would become known as “fan cons,” or fan conventions.

Science fiction remained a fertile ground for fandom. In the 1970s, fans of shows like Star Trek began to focus on the relationships between characters, producing creative works like fan fiction and ”fan vids” that explored character dynamics beyond what was presented in the original media. / THF362462

The bar for fandom in music was set by Beatlemania. From 1963 to 1966, young, passionate, female fans of The Beatles created a subculture unlike any the world had previously seen. Originally, Beatlemania was confined to Britain; the phenomenon went international, though, with the band’s appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. Everywhere the Beatles went, they were followed by screaming fans, captivated by the band’s memorable hooks, accessible themes, and on-stage charisma. This fervor would last until the group’s last stadium concert in 1966. Beatlemania created the template that later boy bands would seek to imitate, and screaming female fans became a staple of boy band concerts into the 21st century.

At the peak of Beatlemania, there was a plethora of Beatles memorabilia available on the market – whether you wanted to represent the band as a whole, or a particular favorite Beatle. / THF92312

Fandom can be more than just a one-way street. The relationship between Taylor Swift and her fans — dubbed “Swifties” — has changed the face of fandom, both inside and outside of the music industry. Throughout her career, Swift has interacted with her fans on social media, teased upcoming projects with “Easter eggs” for them to decode, and at one point even invited them to “Secret Sessions” — exclusive, invitation-only listening parties where select fans, handpicked by Swift, were the first to hear her soon-to-be-released albums. In return, Swift’s fans have catapulted her to incredible heights of success. The relationship between artist and fandom, however, is not without concern, as Swift herself has alluded to the parasocial extent to which some fans have taken the relationship.

In 2024, Time magazine named Taylor Swift their Person of the Year. The level of fandom surrounding her that year was such that she became what writer Sam Lansky called “the main character of the world." / THF722029

History shows that fandoms have the power to shape popular culture. But why do people join fandoms? The same themes — the feeling of acceptance, understanding — crop up in many discussions around the question. So, too, does the topic of escapism — using another world, or even another person, as a distraction from the stress of one’s own life. It is part of human nature to seek inclusion and comfort, to feel as if we belong as part of a group, that we have found a safe space. Perhaps this, then, is the role that fandoms fill, and why they remain a recurring part of our stories.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Pattern, Paint, and Peacocks: An Introduction to the Whimsical Art of the Pennsylvania Germans at The Henry Ford

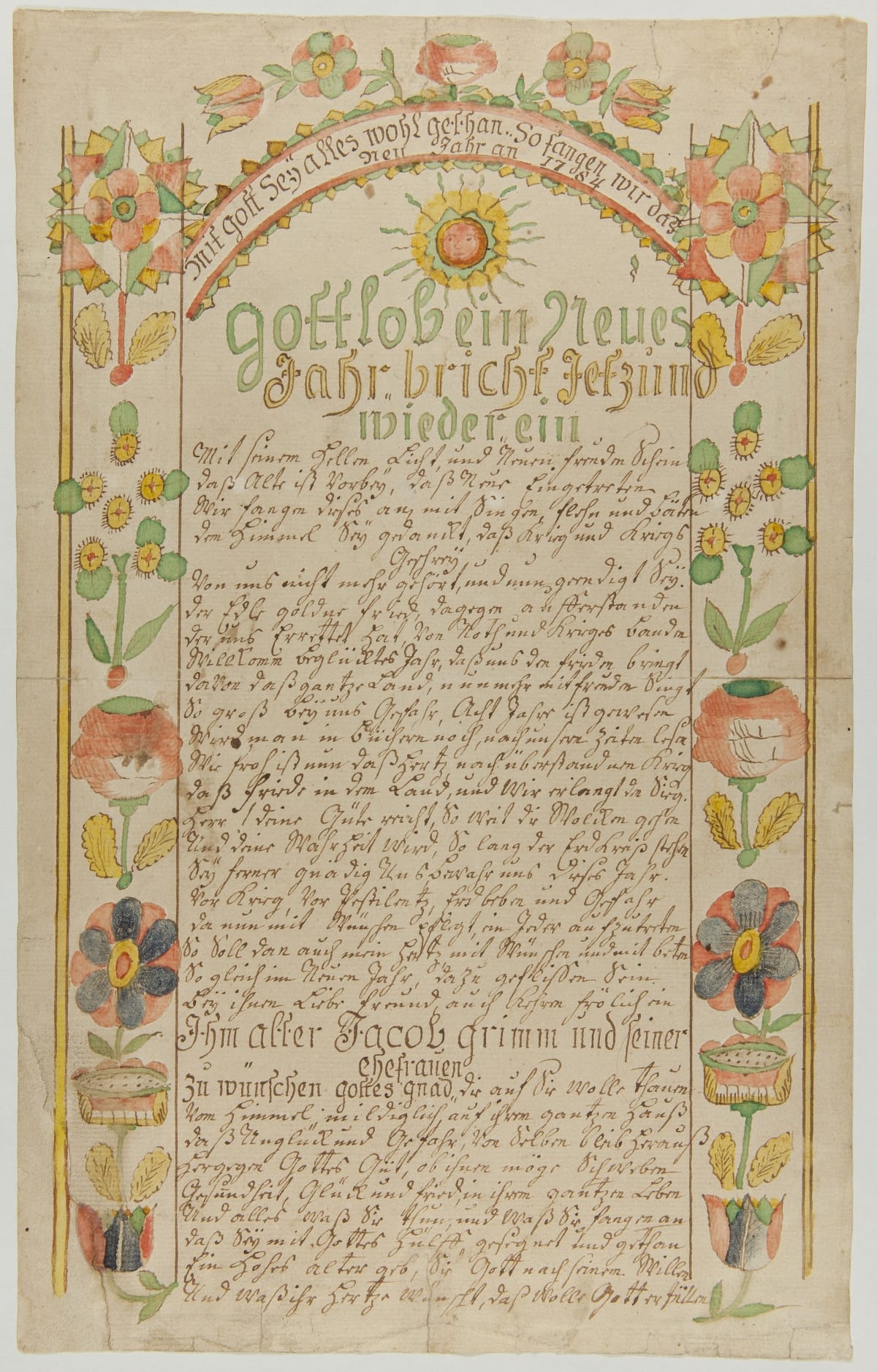

New Year’s Wish for Jacob Grimm and Family, 1784, made by Daniel Schumacher (active 1728-1787), worked in Berks, Lehigh, and Northampton Counties. 61.148.1 / THF237518

The Pennsylvania Germans, popularly known as the Pennsylvania “Dutch” (a corruption of the German word “Deutsche,” which literally means German) were a vibrant immigrant community active in southeastern Pennsylvania in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. By 1790, they made up about forty percent of the population and vied with those of British ancestry as the largest ethnic group. Even in urban areas, such as Lancaster and Philadelphia, the Germans were a sizeable minority.

Within the community itself there was great diversity, although many immigrated from the Palatinate area of southwestern Germany and approximately ninety percent were Protestants, with only ten percent Catholics.

What is remarkable about their legacy is their flamboyant, whimsical, playful, and highly imaginative folk art. They loved to decorate just about every type of household object, from small-scale items like ceramics to large-scale pieces like furniture, with instantly recognizable images. These artists are the most renowned among folk art collectors for their illuminated manuscripts, including marriage and birth certificates, family registers—essentially any type of recorded document. These pieces are called Fraktur.

The Compositions:

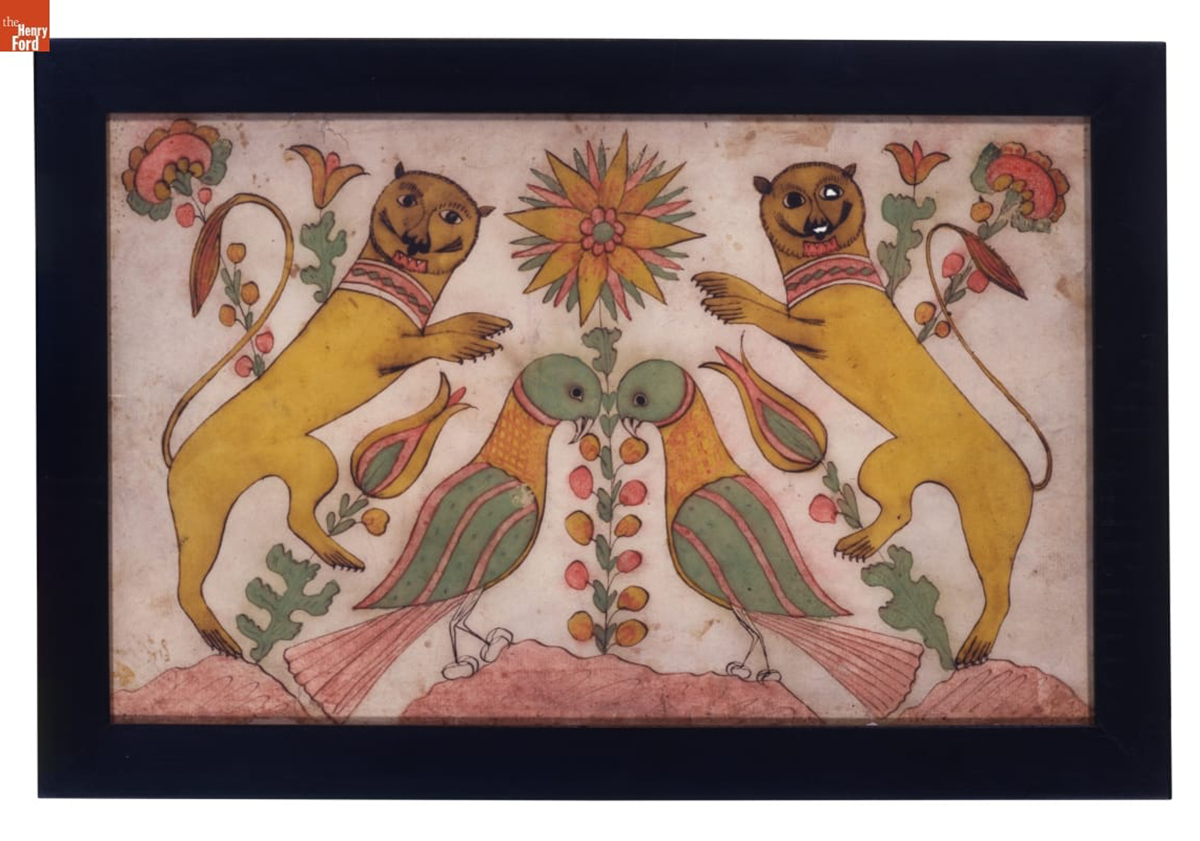

Confronted Lions and Birds, 1800-1820, made by Daniel Otto (active c. 1792-1822) Haines Township, Centre County, Pennsylvania, pen and ink and watercolor on woven paper, 00.3.3038 / THF119526

This Fraktur by Daniel Otto features a stylized central flower where everything on either side balances completely. This symmetry is the hallmark of folk art in general, and Pennsylvania German art in particular. Also note the whimsy or playfulness in the lions—they hardly look ferocious. This is yet another characteristic of Pennsylvania German art.

Decorative Motifs:

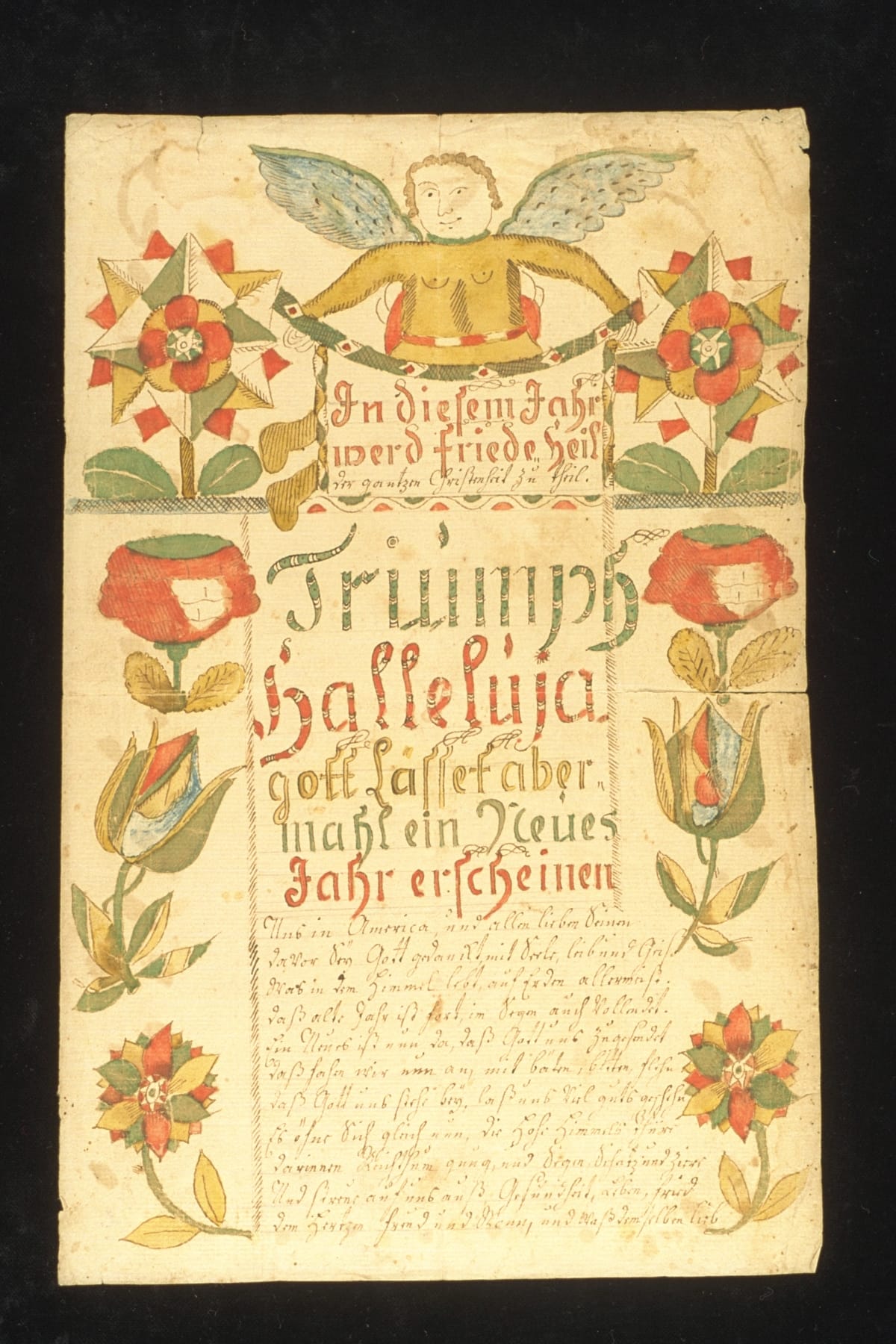

A New Year's Wish for Jacob Grimm and Family, circa 1775, made by Daniel Schumacher (active 1728–1787), worked in Berks, Lehigh, and Northampton Counties, 82.114.5 / THF305642

Notice that this piece, essentially an 18th-century New Year’s card, is symmetrically arranged around the text in the center. The highlight is the angel at the top. What is remarkable are the floral elements on either side. Tulips and stylized flowers are iconic design elements that appear in virtually every piece of Pennsylvania German art.

Another good example is this ceramic storage jar:

Storage jar, made between 1785-1796, made by George Hubener (1757-1828) Limerick Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 59.134.1 / THF177128

At the center of this jar, we find another peacock—which are in fact the 'confronted birds' in the second image above. Here, peacocks stand on the branches of a tree or bush. Notice that on either side, the floral branches terminate in tulip blossoms. Like peacocks or other stylized birds, the tulip is a motif frequently seen in Pennsylvania German folk art.

Reverse side of Storage jar, made between 1785-1796, made by George Hubener (1757-1828), Limerick Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 59.134.1 / THF177132

When we look at the reverse side of the jar, we see a variation of the image on the front. Of course, everything is arranged symmetrically, but instead of a bird at the center, we find a tulip blossom in its place. The space where the tulips were on the front side is now filled with abstracted floral elements.

The same use of symmetry is visible in this image of confronting peacocks:

Confronted Peacocks, 1800-1820, made by Daniel Otto (active c. 1792-1822), Haines Township, Centre County, Pennsylvania, pen and ink and watercolor on wove paper, 29.2085.1 / THF119532

Plate, dated 1818, made by Andrew Headman, (active about 1756-1830), Rockhill Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, 56.54.1 / THF191114

This large plate, used primarily for decoration, is once again highly ornate, with a stylized star at the center. This is surrounded by a circle of triangles in red and green, which in turn is circled by a symmetrical row of ubiquitous tulips.

Furniture:

German American Wardrobe 1790-1800 59.80.1 / THF118499

Like all the examples we’ve seen, this wardrobe is decorated with flowers—some naturalistic, some stylized. It also uses reds against greens, like the plate above. Although called a wardrobe, or Schrank in German, it likely was used in a public room, like a parlor or dining room, where it was meant to impress guests. Of all the examples of Pennsylvania German folk art in the Museum’s collection, this is by far the largest and most impressive.

The Spreading Influence:

Album Quilt, probably made in southeastern Pennsylvania (perhaps in Chester County), circa 1850. One corner of this quilt carries an applied fabric strip with the inked inscription "Anne D. Morrison." 2016.22.1 / THF166494

By the middle of the 19th-century, the design vocabulary of the Pennsylvania Germans spread well beyond their community, encompassing the entire region. For example, we know that this “Album” quilt that utilizes the Pennsylvania German aesthetic was used by Anne Dawson Morrison (1798-1866), a prosperous Philadelphia Quaker.

These objects are just a small sampling of the large folk art collection of The Henry Ford. To see more, please go to https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Rachel Yerke-Osgood, Associate Curator at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

"Everything I Do is Me" - Gwen Frostic

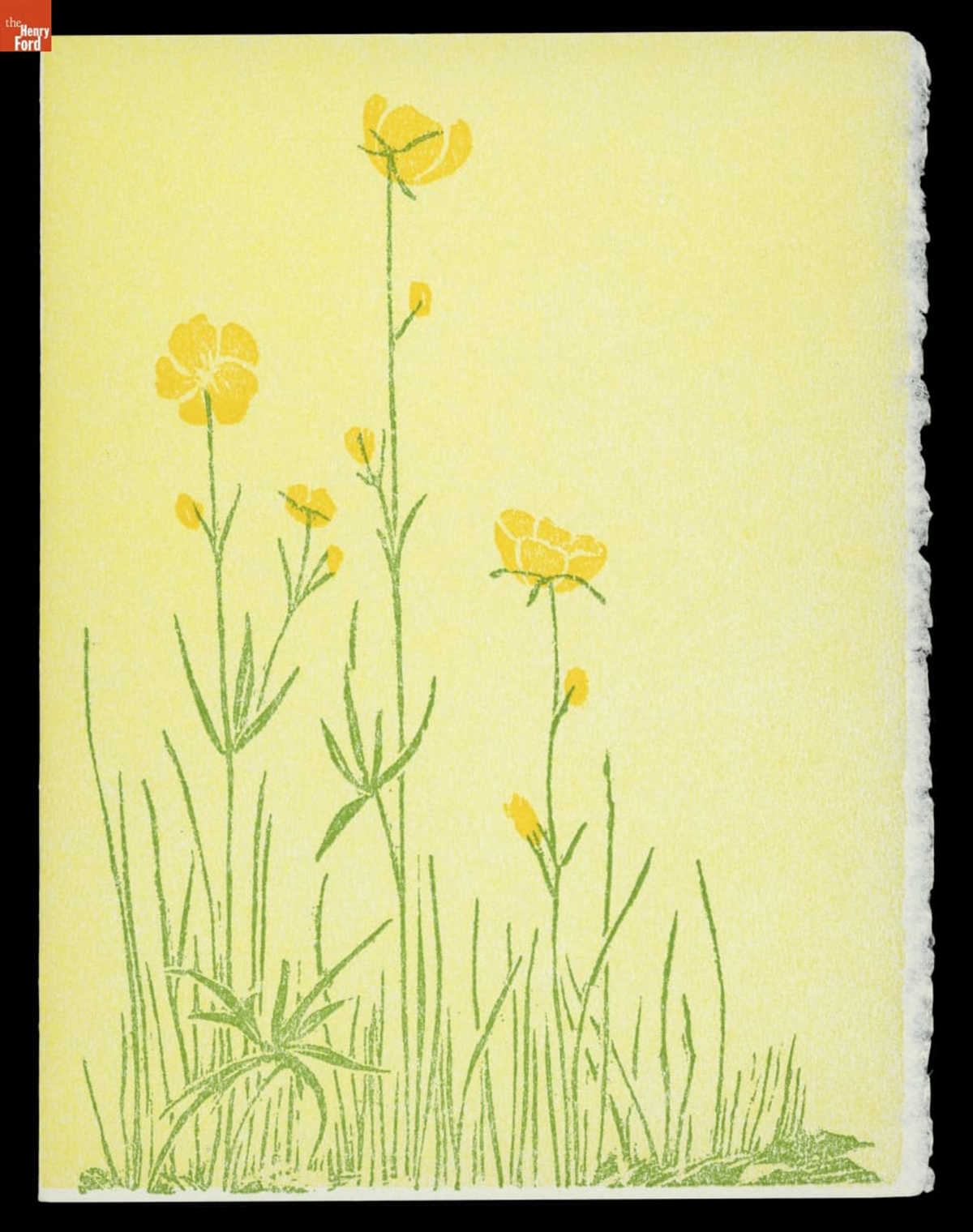

Greeting card created by famed Michigan artist Gwen Frostic, circa 1980 / THF719491

Born in 1906 in Sandusky, Michigan, Sara Gwendolen Frostic lived a many-faceted life. An unidentified illness contracted while still an infant—later assumed to be a mild case of polio, although it also may have been a fever that resulted in cerebral palsy—left Gwen with some physical differences; still, Gwen never considered herself disabled. After her family moved to Wyandotte in 1917, Gwen was exposed to both the sophisticated atmosphere of urban Detroit, and the lush botanical splendor of her family's garden. These two influences would be reflected throughout Gwen’s life, as she became both a successful businesswoman and a well-known advocate for nature.

Despite attending Michigan State Normal College and Western State Normal College (now Western Michigan University), Gwen left school without completing her degree, opting instead to create a metalworking business in her parents’ basement. Gwen’s talent soon drew attention: the Detroit YMCA asked her to teach metalworking classes, Clara Ford commissioned her to make two copper vases, and Monsanto requested that she create a piece for their 1939 World’s Fair display.

Greeting card created from linoleum block carved by Gwen Frostic / THF719495

When World War II redirected the supply of copper that Gwen had been using for her metalwork, she turned to linoleum block printing. Using a press that she disassembled and reassembled to learn how it worked, Gwen began printing commercial letterhead, stationery, and business cards; in between commercial jobs, she sketched her own nature designs and carved them into linoleum blocks. By the war’s end, Gwen was living in the back of her print shop—a set-up that she would continue in for the rest of her life. The business for which she would become most known— Presscraft Papers—had been born.

“Merry Christmas!,” 1955 / THF716787

After the death of her father in 1954, Gwen moved to Frankfort in northern Michigan, setting up a small shop downtown. In addition to selling her nature prints to the summer tourists who came to the scenic bayside town, Gwen developed a mail order trade that exponentially grew her business. In 1957, Gwen wrote her first book, My Michigan. Its style became one that she would use in all her subsequent publications: prose that is almost poetry, printed on thick, deckled paper, alongside charming natural elements printed from Gwen’s linoleum blocks.

For a woman who rarely wanted to talk about herself, her books are perhaps the closest revelation of who Gwen was: an intense thinker, enamored with the natural world around her, with an uncomplicated, pragmatic, yet optimistic view of the world.

On April 26, 1964, Gwen opened the new home of Presscraft Papers: a multi-level store built of trees, rocks, and a sod roof, set amidst a 40-acre swamp property along the Betsie River in Benzonia, Michigan. The main floor of the shop overlooked the print room, where visitors could see the Heidelberg presses that produced the stationery the store sold. On the second floor, carefully concealed from public view, was Gwen’s apartment, featuring two large screened-in porches and floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the property’s pond.

The Heidelberg presses (foreground) and handcarved linoleum blocks (back wall) used to print Gwen’s designs, 2024 / Photo courtesy of Rachel Yerke-Osgood

Despite being tucked in what many would consider to be the middle of nowhere, Gwen’s business thrived. By the 1980s, Presscraft Papers had made Gwen over a million dollars, as visitors flocked from across the state, across the country, and around the world. In addition to her business success, Gwen also received numerous awards and special recognitions. In 1978, May 23 was declared Gwen Frostic Day in Michigan. In 1986, she was inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame. Rather than resting on her laurels, Gwen continued to create new designs and tend to her business well into her 90s.

In 2001—one day before her 95th birthday—Gwen passed away. Her shop remains, though, little changed from when Gwen herself lived and worked there. Much as the ducks still flock to the pond Gwen loved so much, visitors continue to flock to the store. While many come to shop, others come simply to drink in the tranquility of their surroundings and the charm of Gwen’s designs.

Gwen Frostic Prints, home of Presscraft Papers in Benzonia, Michigan / Photo courtesy of Rachel Yerke-Osgood

This, then, is the legacy that Gwen Frostic carved for herself as she carved her linoleum blocks: a gifted artist, a determined woman, and a devout lover of the natural world.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an associate curator at The Henry Ford.

Symbols in Simplicity: The Photography of Margaret Bourke-White

Photojournalism at its best has the power to extend beyond being merely documentary; at its finest, it is intended to make the viewer think or feel something about the subject matter. In the early part of the 20th century, photojournalism saw a new boom, and the field was led by innovative photographers — many of them women — with opinions about the subjects they shot. Among these pioneers was Margaret Bourke-White.

Margaret Bourke-White was born on June 14, 1904, in New York City. Her father, Joseph White, was a factory superintendent and inventor with a mind for machinery; her mother, Minnie Bourke, was a homemaker who firmly believed that Margaret should not be impacted by traditional gender limitations. From a young age, Margaret shared her father's interest in the mechanical, while also longing for a career that would offer adventure and excitement. In 1924, she married photographer Everett Chapman, but the marriage dissolved in 1926. After graduating from Cornell University in 1927, she moved to Cleveland to pursue a career in commercial photography.

Continue Reading