Posts Tagged clara ford

Clara Ford’s Travel Diaries

When traveling today, it is easy to document our journey through swift clicks of our phones and cameras. The people, sights, and sounds of a moment are captured and recorded through photos, videos, and social media posts making it easy to reflect on where we were and what we enjoyed.

The desire to document a memorable trip has remained a common tradition and in the age of Clara Ford, was accomplished through travel journals or diaries. Even with the advent of photography, film had to be thoughtfully allocated to document the most meaningful memories from a trip.

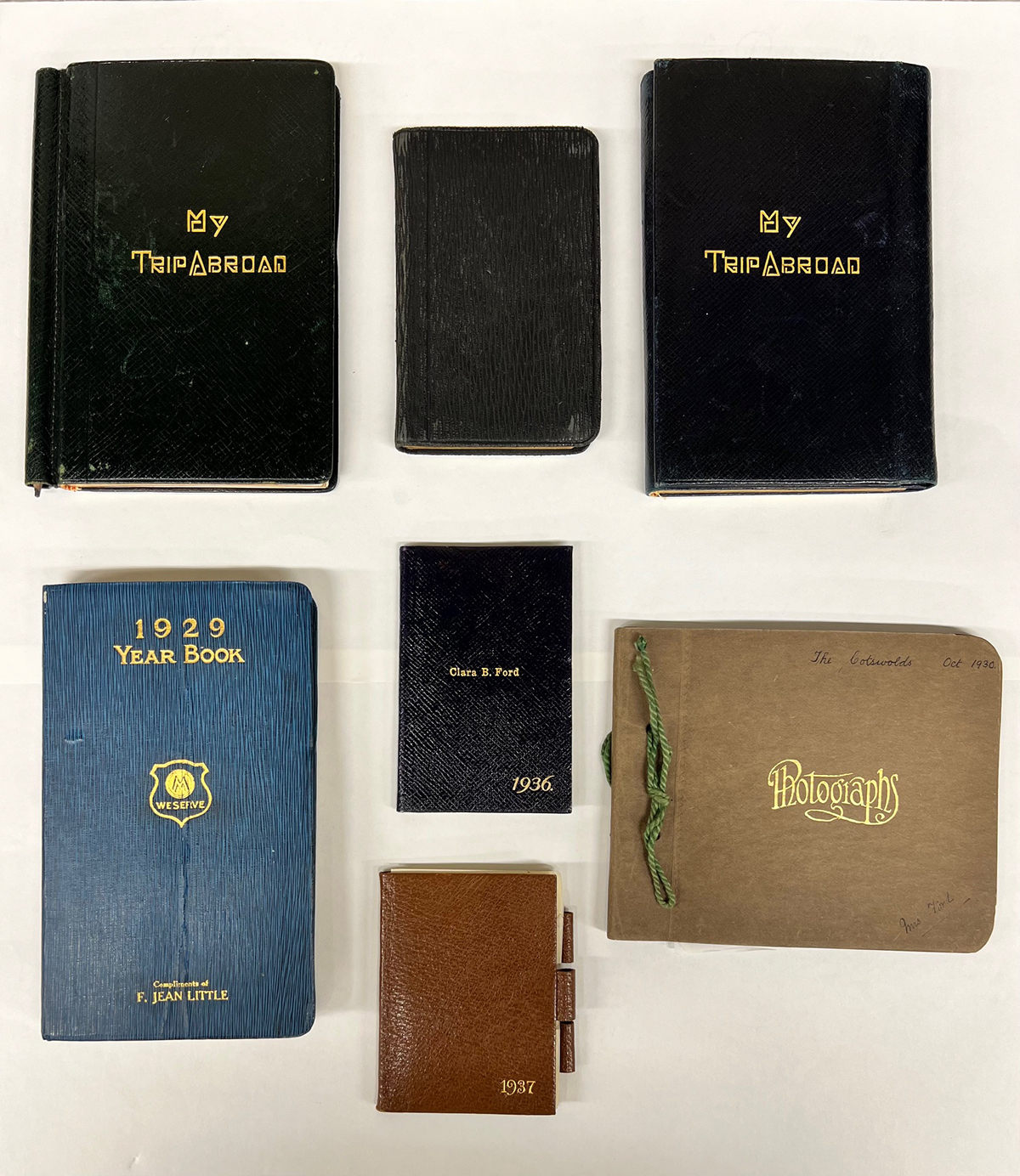

The Henry Ford's collections include several travel diaries written by Clara Ford dating from 1912 to 1945. Clara did not keep a diary for every trip she took. As the wife of Henry Ford, her travels were frequent and varied. Most of the diaries document her travels overseas, a momentous journey for anyone at that time, and winter retreats to Richmond Hill, Georgia, and Fort Meyers, Florida.

Clara Ford Travel Diaries. Accession 1, Box 105 and 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Unlike social media posts, travel diaries were not always intended for sharing or future publication. Entries were meant to document travel details and for personal reflection.

This means the writer was often sharing their thoughts more freely. For a notable figure like Clara Ford, travel diaries provide insight into her personal opinions and interests that might have been left out of an official record of her travels. They also provide a valuable record of Clara at a given time and place. They tell us who she interacted with, where she stayed, and what she saw.

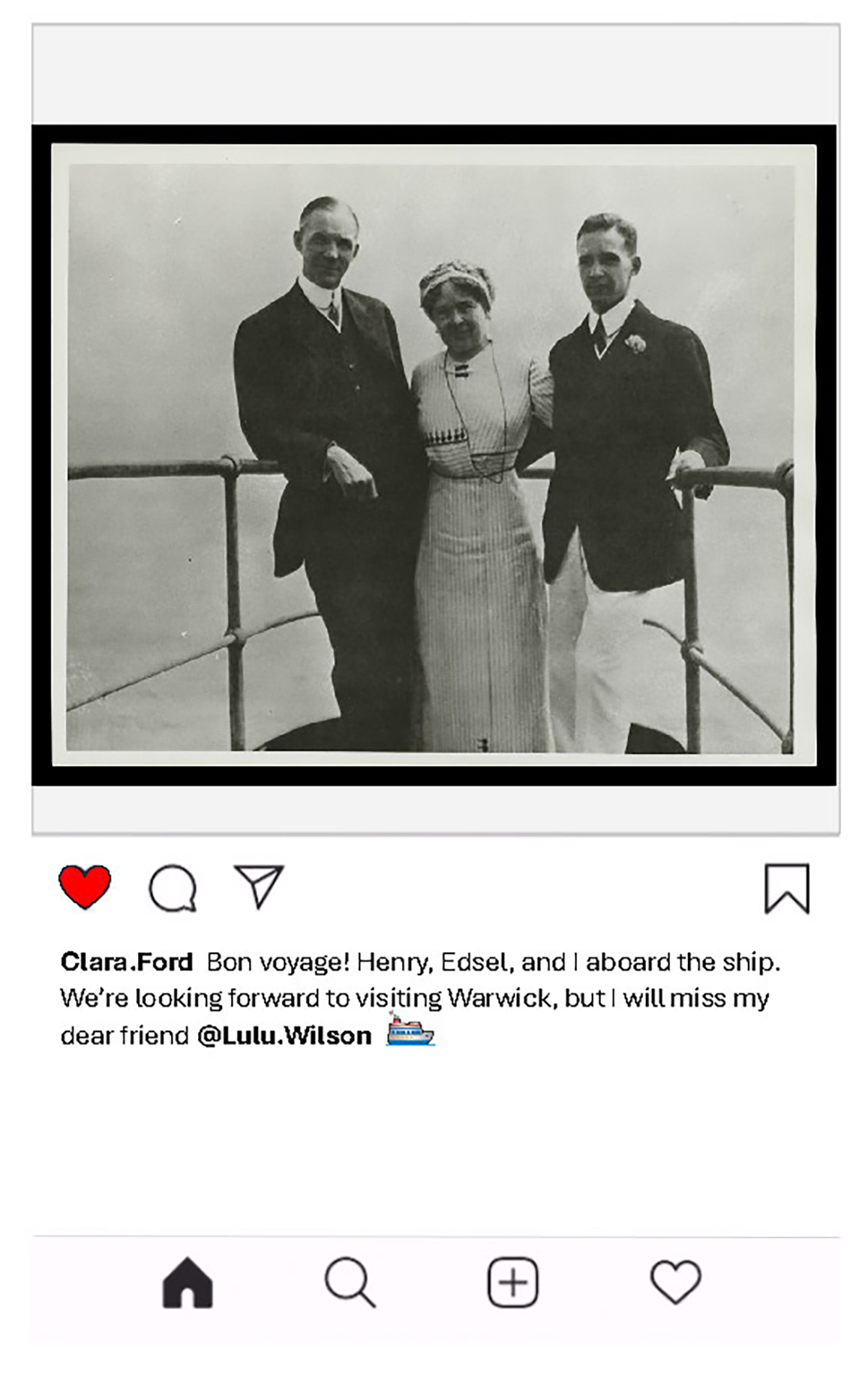

The earliest travel diary penned by Clara was for her first trip to Europe in 1912. She, Henry, and Edsel explored sites throughout Great Britain and France.

Henry, Clara, and Edsel Ford aboard Ship on their European Trip, 1912. / THF117563

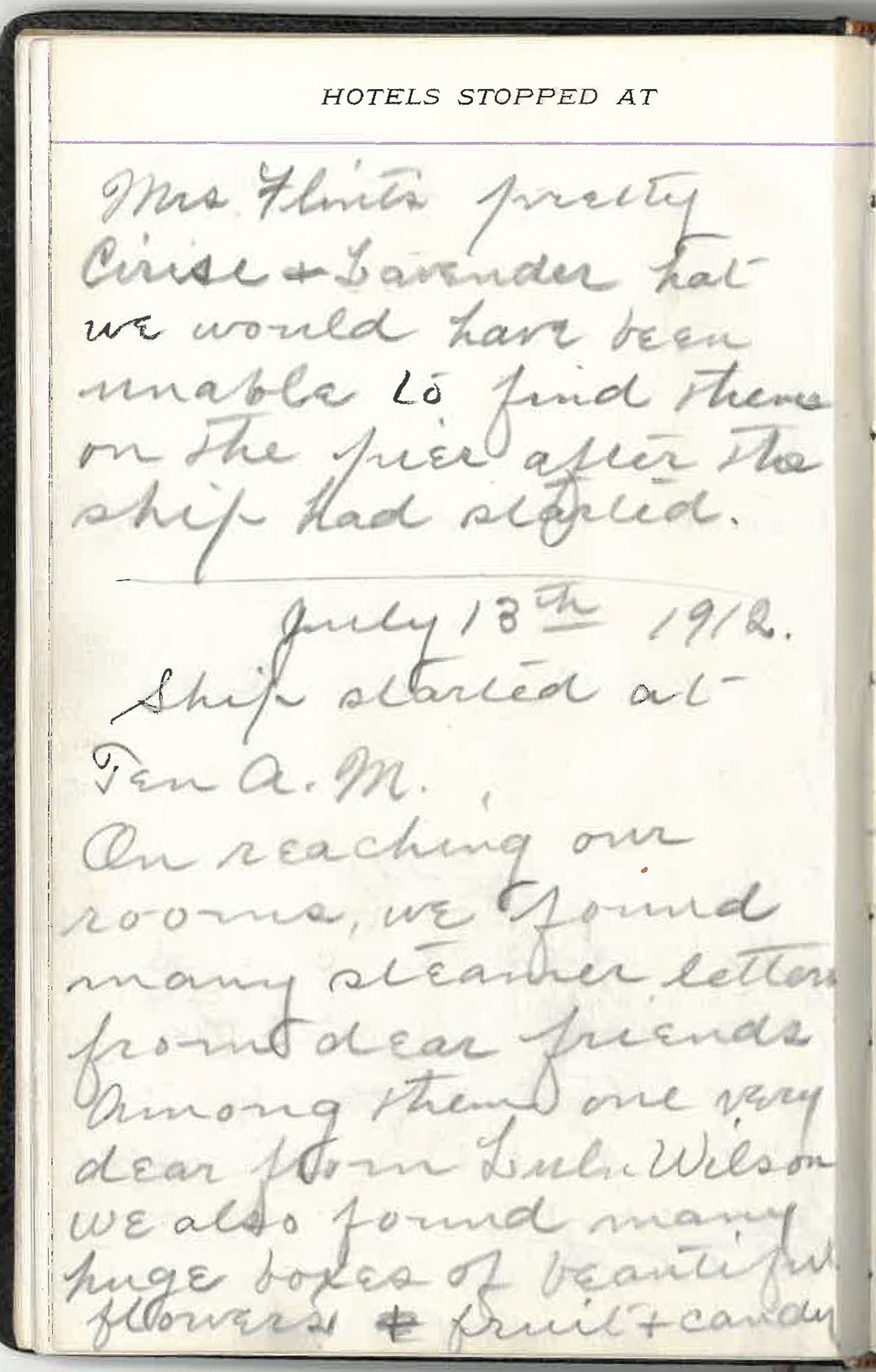

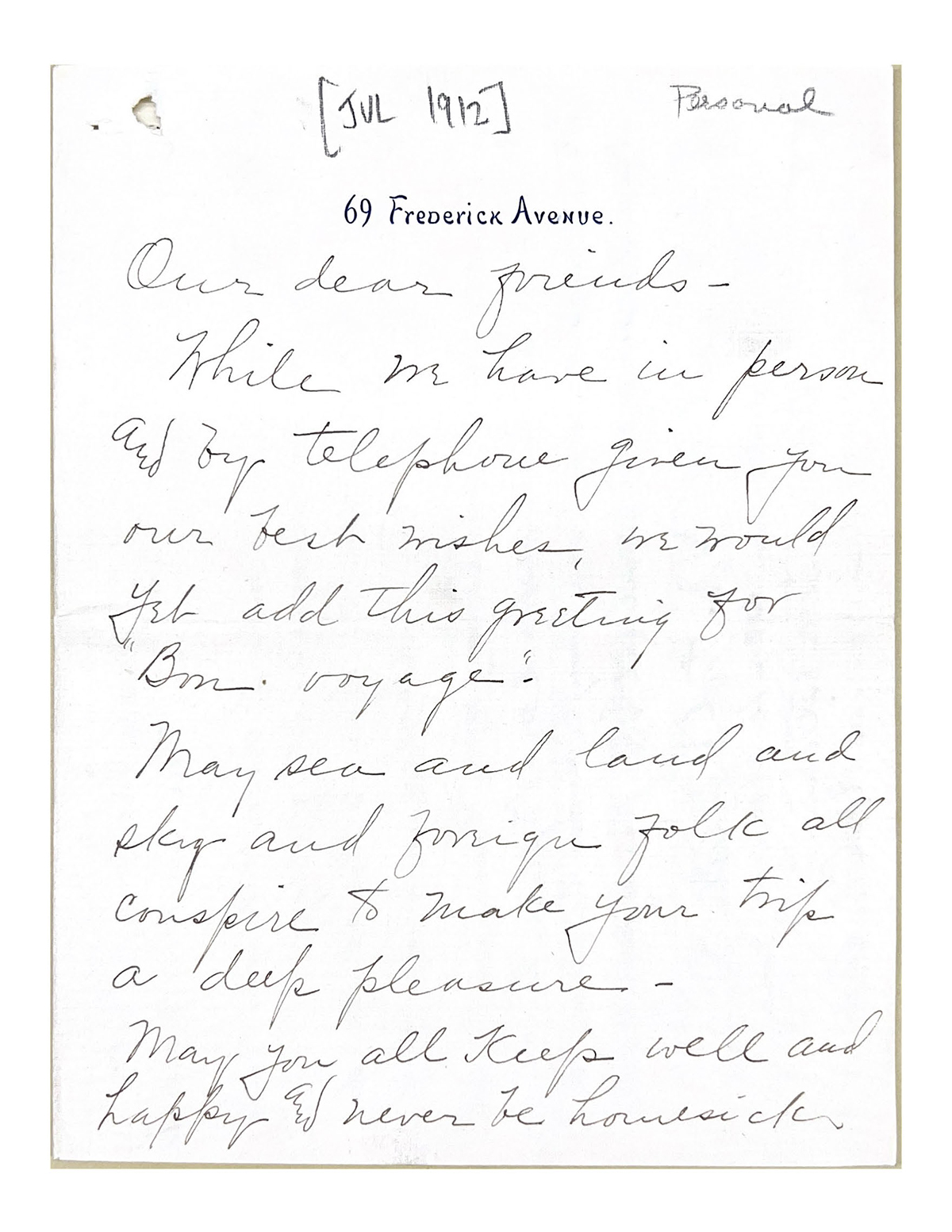

In one of the first entries, Clara documents the time the ship set sail and describes the warm welcome they received. Among flowers, fruits, and candy were several letters from friends wishing them a “Bon Voyage!” Clara references a letter from her close friend, Lulu Wilson, which we also hold in our collection. Connecting archival records like these illustrates a larger picture for historians and researchers.

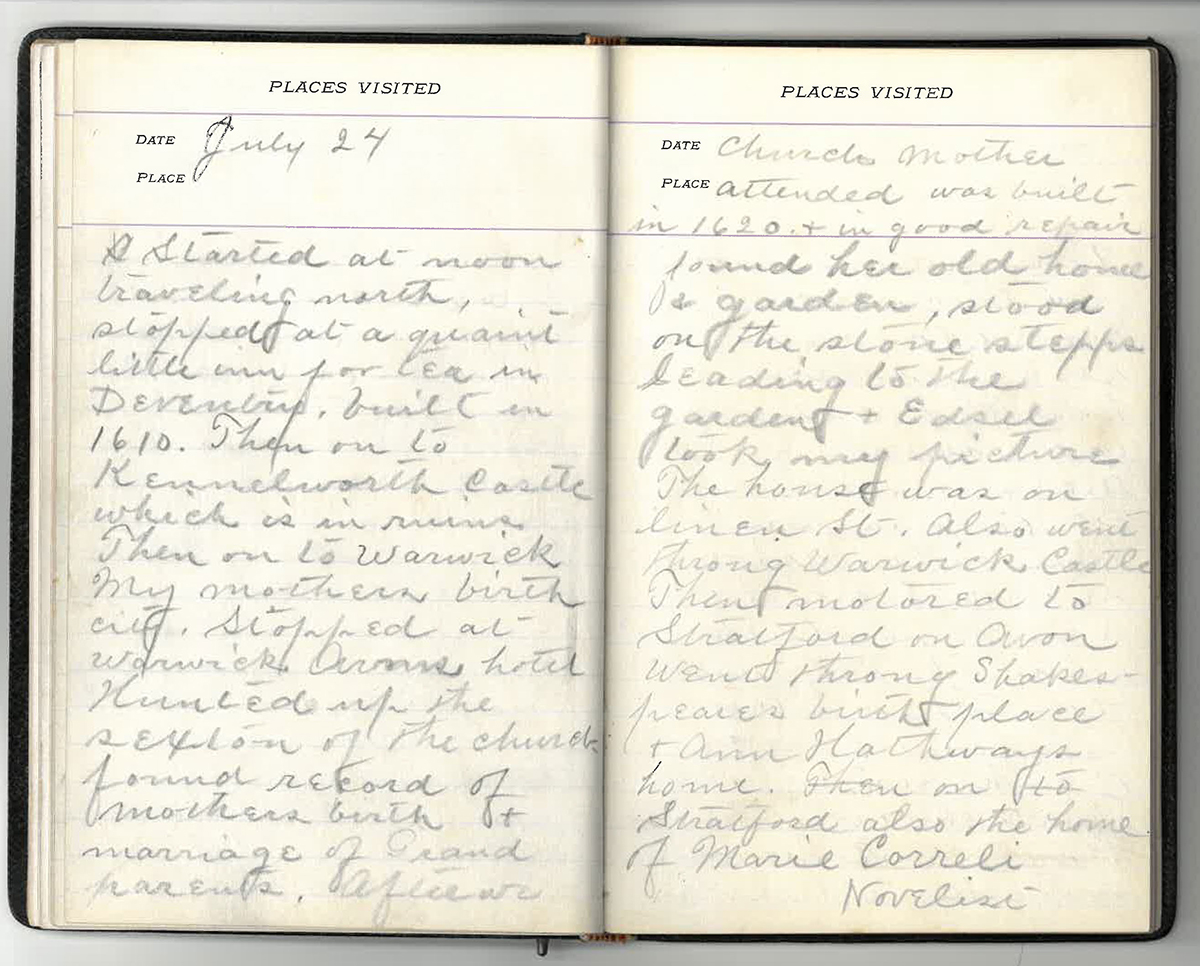

Clara Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Letter to Clara Ford from her friend Lulu Wilson, July 1912. Accession 1, Box 66. / Image by Lauren Brady

In addition to Clara's diary, we also have Edsel's diary from this trip in our collection.

Clara Ford's and Edsel Ford's Travel Diaries, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

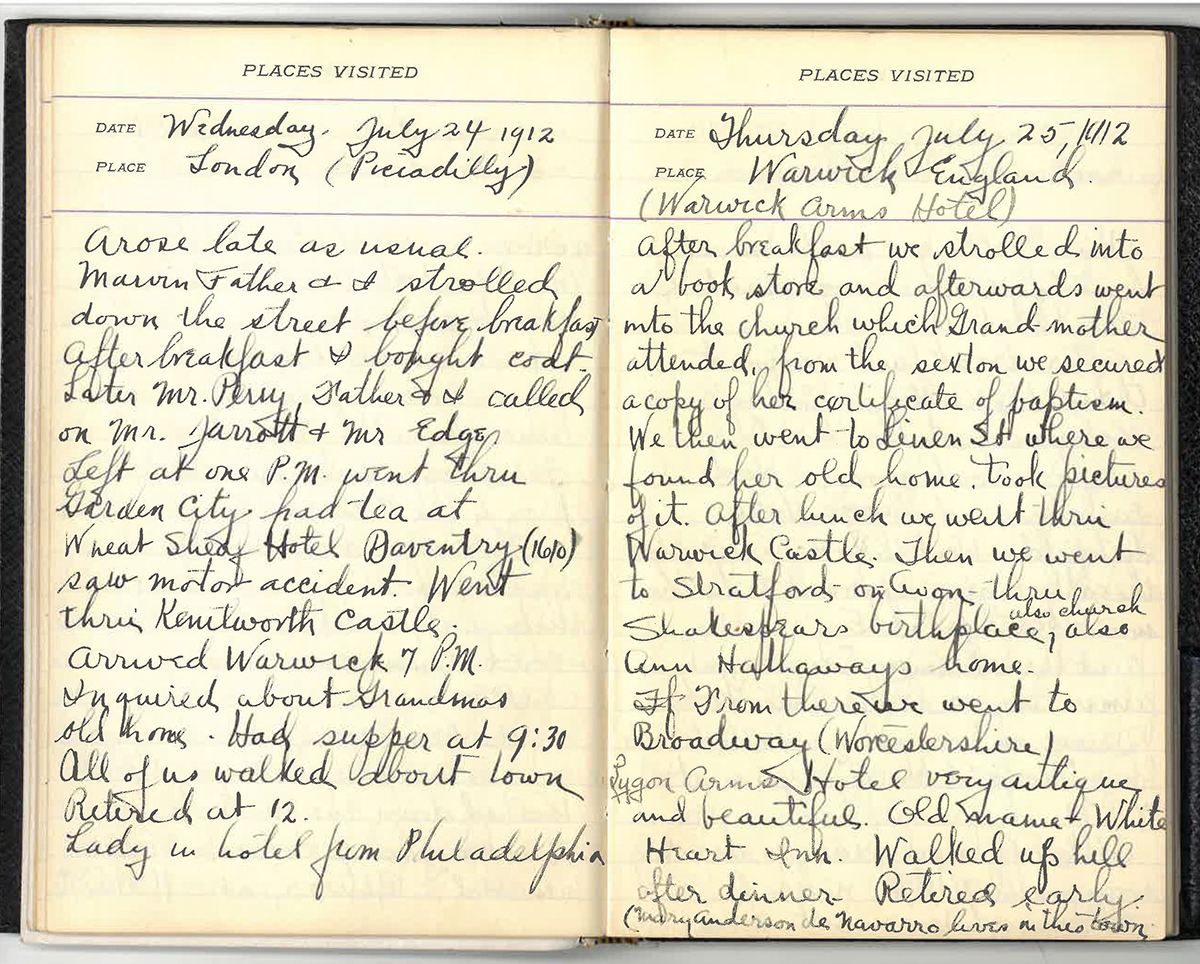

During their travels, they visited Clara's ancestral home. There are parallel accounts of the visit in both diaries. It reads as a meaningful visit for Clara who also describes important genealogical details about her family history that may not have been recorded elsewhere in our archival collections.

Edsel Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Clara Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

The Fords returned to Europe many times, including a trip in 1930 which Clara documented in a diary and a unique photo album. In her diary, Clara makes note of Henry's visit to Buckingham Palace before he departed for the Cotswold region of England where Cotswold Cottage had recently been acquired for Greenfield Village.

This visit received special commemoration in a photo diary with handwritten notes by Clara.

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

The album includes several snapshots of their visit culminating with a group photo at the former site of Cotswold Cottage. Clara's notes read like a short story as she describes the photos and recounts details.

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Clara's diary entries with descriptions of cities and historic sites she encountered are valuable to historians looking for written records of landscapes altered by wars and other major events. Her words help us understand Clara Ford as a historical figure, but they also help us understand a location as it stood at that moment in time.

We are grateful to have these valuable archival records, but it is fun to wonder how a modern Clara may have documented her travels. Perhaps a post like this...

If you have any questions or would like to learn more about our collections, please contact the Benson Ford Research Center at research.center@thehenryford.org.

Lauren Brady is a reference archivist at The Henry Ford.

Edsel Ford, Ford family, Henry Ford, Clara Ford, by Lauren Brady

Sidney Houghton: The Later Commissions

Cover of Sidney Houghton Brochure. / THF121214

From Houghton’s reference images in the brochure, we can document many commissions that are lost as well as provide background for some that survive. This post centers on Houghton’s later work for the Fords, and my evaluation of why the relationship ended.

The Dearborn Country Club

Dearborn Country Club in 1925. / THF135797

Dearborn Country Club in 1927. /THF135798

According to Ford historian Ford Bryan in his book, Friends, Families & Forays: Scenes from the Life and Times of Henry Ford, the Dearborn Country Club was created for executives at the Ford Motor Company. By the middle of the 1920s, Ford’s operations were centered in Dearborn, with nearly all the company’s upper echelon working from the Ford Engineering Laboratory or the nearby Ford Rouge Plant. According to Ford Bryan, the idea came from Henry and Clara Ford to provide Dearborn with the same amenities as elite suburbs such as the Grosse Pointes or the northern suburbs. They also wanted their associates and friends to have the best that money could buy. The project was an incentive for Ford executives to remain in Dearborn, but proved to be unprofitable for the company. Further, when Henry Ford tried to impose his wishes against smoking and drinking, the membership essentially ignored him. Because of this, the Fords rarely visited the Club.

Architect Albert Kahn, who famously designed the Rouge Plant, was hired to design the clubhouse, seen above. The building was finished in the fall of 1925 and was designed in the “Old English” or Tudor style, popular in England in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Formal Dance at the Dearborn Country Club, 1931. / THF99871

Dearborn Country Club Chef at Banquet Table, 1931. / THF99875

Light's Golden Jubilee Ushers at the Dearborn Country Club, October 21, 1929. / THF294674

We know through documents that Sidney Houghton worked on the interiors. What we have in the way of documentation is a furnishings plan, but little else. Period photos, such as those above, show the elaborate beamed ceiling in the ballroom designed by Albert Kahn, and the elegant lighting and window treatments, likely provided by Houghton.

Henry Ford Hospital and Clara Ford Nurses Home

Henry Ford Hospital and Clara Ford Nurses Home, 1931. / THF127760

Clara Ford Nurses Home, 1931. / THF127754

Nurses in front of Clara Ford Nurses Home, 1926. / THF117484

One of Henry Ford’s great humanitarian efforts was in founding Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. It was created in 1915 and in 1917 was turned over to the federal government during World War I for military use. By the middle of the 1920s, the hospital was considered the major medical center in Detroit. In 1925, Clara Ford organized the Henry Ford Hospital School of Nursing, and she funded the building housing it, the Clara Ford Nurses Home, on the hospital campus.

Living Room inside Clara Ford Nurses Home, 1925. / THF127777

Only one photograph of the original interior survives, showing the living room on the first floor. This is absolutely the work of Sidney Houghton, done in what he would call the Elizabethan or Tudor style. The walls are covered with heavy, inlaid panels and the furniture is heavily proportioned, with carved turnings. The wood of choice during this period was oak, which Houghton described as the “Age of Oak.” The upholstered furniture is likewise heavy and large in scale.

Houghton Brochure: A Tudor Interior. / THF121227b

Houghton Brochure, Furniture from the "Age of Oak." / THF121217a

The End of the Relationship

By 1925, Houghton’s commissions were at or nearing completion. After this date, there is an abrupt end to the correspondence between Houghton and the Fords. The only subsequent communications are a telegram from 1938, congratulating the Fords on their 50th wedding anniversary, and a letter dating to 1941, thanking Henry Ford II for his work on supplying aid for Britain during the second World War. While we have no documentation on how the relationship ended, we do have documentation of one artifact that may shed light on this period. In 1925, Houghton gave the Fords a sterling silver model galleon or ship. Perhaps this is a reference to Houghton’s love of sailing. It appears on the cover of the Houghton brochure at the top of this post.

Was this a peace offering from Houghton to the Fords? Or was it a token of generosity from Houghton, a great navigator, to the Fords? We will never know, but it is interesting to contemplate the implications of this extraordinary gift.

I hope you’ve enjoyed my journey through an unknown aspect of the Fords’ life. Researching and writing about Sidney Houghton has been a pleasure.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- Sidney Houghton: The Fair Lane Rail Car and the Engineering Laboratory Offices

Table, Used as a Writing Desk by Mark Twain, 1830-1860 - Women Design: Peggy Ann Mack

- The Webster Dining Room Reimagined: An Informal Family Dinner

design, healthcare, Detroit, Michigan, Dearborn, Clara Ford, Henry Ford, Sidney Houghton, furnishings, decorative arts, by Charles Sable

Sidney Houghton: The Fair Lane Estate

In my last two blog posts (“The Enigmatic Sidney Houghton, Designer to Henry and Clara Ford,” and “Sidney Houghton: The Fair Lane Rail Car and the Engineering Laboratory Offices”), I discussed how Sidney Houghton (1872-1950), a British interior designer and interior architect met and befriended Henry Ford during World War I, and worked on projects like Henry Ford’s yacht Sialia, Henry and Clara Ford’s private railcar Fair Lane, and offices for Henry and Edsel Ford in the Ford Engineering Laboratory in Dearborn, Michigan. This blog centers on the most intimate of Houghton’s work for the Fords, the Fair Lane estate.

(For clarity’s sake, it is important to note that the Fair Lane estate is a historic house museum, independent of The Henry Ford. The house is currently undergoing a major restoration. You can learn more about the Fair Lane estate here.)

The Fair Lane Commission

Cover of Houghton Brochure / THF121214

The single document that best details the relationship between Sidney Houghton and the Fords is a brochure, more a portfolio of projects, published by Houghton in the early 1930s, to promote his design firm. From Houghton’s reference images, we can document many commissions that are lost as well as provide background for some that survive. Unfortunately for us, images of Fair Lane were not included in the 1930s Houghton brochure, likely because of the private nature of the commission.

However, The Henry Ford’s Benson Ford Research Center holds exterior and interior photographs of the house, taken at a variety of dates. Additionally, our archives holds a select group of Houghton’s designs for Fair Lane’s furniture. These are the only surviving drawings of Houghton’s Ford-related furniture. One of my greatest joys in researching this blog was locating the completed pieces of furniture in historic photographs.

The Story of Fair Lane

The story of Fair Lane began in 1909, when Henry Ford bought large tracts of land in Dearborn Township, the place of his birth. At that time, Henry, his wife, Clara, and their son, Edsel, were living comfortably in the fashionable Boston-Edison neighborhood of Detroit, not far from the Highland Park plant where the famous Model T automobiles were manufactured. Henry was considering options for building a larger home, where he and his family could have more space and greater privacy. They were also considering building in Grosse Pointe, a community where many of Detroit’s leaders of industry were constructing homes. They even bought a parcel of land there that eventually became the site of Edsel and his wife Eleanor’s home in the 1920s.

In the summer of 1909, Ford visited the renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright in his Oak Park, Illinois, studio. The result was a commission for a large estate along the Rouge River in Dearborn. Scholars believe that Henry Ford heard about Wright from one of his chief engineers and neighbor, C. Harold Wills, who previously contracted Wright to build a home for his family in Detroit. By November of 1909, Wright had closed his studio and turned his practice over to the Chicago architectural firm of Von Holst and Fyfe, with his best draftsperson, Marion Mahony, overseeing all of Wright’s remaining projects. Wright felt that his architectural practice was at a “critical impasse” and went to Europe to work on a summary portfolio of his career, published in 1910. He was accompanied by Mrs. Mamah Borthwick Cheney, the wife of a client. This scandalous situation seems not to have affected the Fords, as Marion Mahony continued work on Fair Lane.

Presentation Drawing of Fair Lane, 1914 / THF157872

The project continued slowly through the next few years, until circumstances in the Fords’ lives made securing a new home a priority. In January 1914, Henry Ford announced his famous “five dollar day” wage for factory workers. His home on Edison Avenue near the plant was besieged by job seekers and the Fords lost any semblance of privacy. They soon realized that that the new Dearborn house was a priority. In February 1914, Clara Ford, who had taken the leadership role on the new house, called a meeting of Von Holst, Mahony and related designers. A number of elegant presentations of the home were shown to Clara Ford, including the design above. Many of these are now in public collections and give us a sense of the proposed estate. Two can be accessed here and here.

Instead of continuing to work with Marion Mahoney, Clara Ford chose Pittsburgh architect William Van Tine to complete the house. Van Tine was known in New York and the East, and it is generally thought that Clara Ford was seeking to emulate the tastes of women of her social status. Another key factor was the direction of American taste: the Prairie style promoted by Frank Lloyd Wright and Marion Mahony was rapidly losing currency and Americans increasingly favored revival styles, including Colonial and Medieval Revivals.

Fair Lane as Built

Fair Lane from the Rouge River, 1915 / THF98284

Fair Lane Entrance, 1916 / THF149961

When I look at images of Van Tine’s house, completed in early 1916, I am struck by the odd composition, such as the sloping horizontal rooflines, especially to the left of the front entrance. These seem derived from Marion Mahony’s designs. There are vertical, castle-like forms, such as the one just to the right of the entrance, which are not at peace with the rest of the house. The result is a hodge-podge of disharmonious elements that barely coexist with each other.

Planting Plan for Fair Lane Grounds Number 5, November 1915 / THF155894

The planting plan above gives us a sense of Van Tine’s arrangement of the house. To the far left is Henry Ford’s power house, which is connected to the house through a tunnel under the rose garden. The tunnel ends near the indoor swimming pool intended for son Edsel’s use.

Entry Hall from the Living Room around 1925 / THF126547

Library in 1951 / THF98258

Living Room in March 1916 / THF126073

The main rooms of the house are indicated in an area labeled as “residence” on the plan. The first-floor entrance consists of a grand hall and wide staircase. To the right of the hall is a small library. The hall leads into what the Fords described as their living room, the heart of the house. At the rear of the photograph above, please note the player organ installed in late 1915.

Music Room in 1951 / THF126543

The entrance to the music room is to the right of the player organ in the living room. It is by far the largest and grandest room in the house. The photograph above shows it in its final incarnation, shortly after Clara Ford’s death.

Dining Room in 1925 / THF98262

The dining room leads off the living room and is another grand room, although it lacks the scale of the music room. As you can see, all the large public rooms at Fair Lane are rather dark and heavily decorated.

Sun Porch, Identified as the Loggia on the Ground Plan, about 1925 / THF137033

The sun porch is unlike any other public room in Fair Lane. It was filled with light and was said to have been one of the Fords’ favorite rooms. Also, unlike the rest of the house, it was filled with wicker furniture.

As you can see, Fair Lane was a very dark and heavily decorated home. We know that the Fords—Clara in particular—were unhappy with the interior. For example, sometime in the 1920s or the 1930s, Clara Ford went so far as to paint the walnut paneling in the music room. This north facing room must have appeared very dark, especially on a cloudy winter day.

Sidney Houghton’s Work at Fair Lane

Records in the Benson Ford Research Center indicate that Sidney Houghton began consulting on furnishings for Fair Lane in 1919. The records and correspondence continue through 1925, with proposals and payments through the entire period. The only “before” and “after” photographs that we have are of the living room.

Living Room in 1919 / THF132991

Living Room in 1940 / THF136074

By 1940, the furnishings of 1919 have been completely removed. The clutter of the 1919 furnishings have been replaced with groups of furniture oriented around the fireplace. The whole arrangement appears coherent and logical. The furniture styles of the 1940 living room are a mixture of historic English and American. Is this the work of Sidney Houghton? While we know that Houghton was working extensively at Fair Lane, we have no surviving renderings for furniture in this room.

Houghton’s Documented Designs for Fair Lane

Master Bedroom in 1951 / THF149959

Like the living room, the master bedroom contains a mixture of furnishings in historic English and American styles. For example, the mantelpiece is described as a “Wedgewood,” as the colored decoration derives from Wedgewood’s English Jasperware, first made in the 18th century. There are also pieces that are American in origin, such as the William and Mary–style table in front of the fireplace, and the Federal-style slant front desk in the corner, to the right of the window.

This room also contains two twin beds, likely designed by Sidney Houghton. They are made of veneered walnut with inlaid medallions done in a Chinoiserie style, a western interpretation of oriental design.

Design by Sidney Houghton for Fair Lane, Bed, 1921-1923 / THF626014

The headboard and footboard, as well as the crest rail and legs, of this bed are identical to those on the twin beds in the 1951 photograph. Houghton may have presented this design to Clara Ford, and she chose to have twin beds without a canopy produced instead.

Master Bedroom in 1951 / THF149955

The opposite wall in the master bedroom shows us again a combination of English and American historic furniture. They include an American Queen Anne oval table in the left corner. To the right of it is a Queen Anne style dressing table, partly obscured by an upholstered armchair. What is of interest is the dressing table and mirror at the center of the back wall. These are Houghton’s designs.

Design by Sidney Houghton for Fair Lane, Bedroom Dressing Table and Looking Glass, 1921-1923 / THF626012

We can see that the dressing table matches the bed—the inlaid medallions are also done in a Chinoiserie style—so this appears be part of a bedroom suite. Indeed, there is another design that does not appear in the room.

Design by Sidney Houghton Design for Fair Lane, Bedroom Cabinet or Chest, 1921-1923 / THF626016

This piece likely was presented to Clara Ford and rejected, or, if produced, removed before the photograph was taken in 1951.

Design by Sidney Houghton for Fair Lane, Chest of Drawers and Case, possibly for Bedroom, 1921-1923 / THF626010

This chest of drawers appears to relate to the bedroom suite, as it is similar in scale, although it lacks the inlaid medallions.

Design by Sidney Houghton for Fair Lane, Ladies Writing Table, 1921-1923 / THF626008

This elegant ladies desk may have been intended for the Fords’ bedroom. Like the chest, it may have been rejected or removed later.

The Benson Ford Research Center holds more of Houghton’s furniture designs for Fair Lane, although none appear in the historic photographs.

Design by Sidney Houghton for Fair Lane, Center Table or Partners Desk, 1921-1923 / THF626002

This heavy, masculine-looking piece was likely not part of the bedroom suite. If fabricated, it would have been a large, clunky piece of furniture.

Design by Sidney Houghton for Fair Lane, Side Table, 1921-1923 / THF625998

This piece, done in the Louis XV or 18th-century Rococo style is a departure from anything visible at Fair Lane. Clara Ford likely rejected it.

There are also Houghton sketches and working drawings in the archive.

Design by Sidney Houghton for Fair Lane, Slant Front Desk and Chair, 1921-1923 / THF625994

Design by Sidney Houghton for Fair Lane, Side Table or Stool, 1921-1923 / THF626000

These designs were likely drawn on-site and presented as ideas for Clara’s approval.

Conclusion

As these drawings suggest, Sidney Houghton was extremely talented. He could work in a variety of styles and produced high-quality furniture. He transformed Fair Lane during the early 1920s from an eclectic mix to a more simplified combination of 18th-century English and American styles. This post represents the beginning of inquiry into the role of Houghton at Fair Lane, which should be continued over time. My next blog post will examine Sidney Houghton’s later work for the Fords and the end of their relationship.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- Armchair Made from Longhorn Steer Horns, 1904-1910

- Prototype Eames Fiberglass Chair, circa 1949

- Sidney Houghton: The Fair Lane Rail Car and the Engineering Laboratory Offices

- Creatives of Clay and Wood

20th century, 1920s, 1910s, Sidney Houghton, research, Michigan, home life, Henry Ford, furnishings, drawings, design, decorative arts, Dearborn, Clara Ford, by Charles Sable, archives

Fair Lane: The Fords’ Private Railroad Car

Fair Lane, Henry and Clara Ford’s private railroad car. / THF80274

Fair Lane, Henry and Clara Ford’s private railroad car. / THF80274Fair Lane, the private Pullman railroad car built for and used by Henry and Clara Ford, turns 100 years old in 2021. It provides a fascinating window into business and pleasure travel for the wealthy in the early 20th century.

By 1920, the Fords found it increasingly difficult to travel with any degree of privacy. Henry, in particular, was widely recognized by the public. He’d been generating major headlines for a decade, whether for his victory against the Selden Patent, his achievements with mass production and worker compensation via the Five Dollar Day, or his misguided attempt to end World War I with the Peace Ship. The Fords could travel privately for shorter distances by automobile, and their yacht, Sialia, provided seclusion when traveling by water. But anytime they entered a railroad station, the couple was sure to be pestered by the public and hounded by reporters. Their solution was to commission a private railroad car for longer overland trips.

Private railroad cars are nearly as old as the railroad itself. America’s first common-carrier railroad, the Baltimore & Ohio, opened in 1830. Little more than ten years later, President John Tyler traveled by private railcar over the Camden & Amboy Railroad to dedicate Boston’s Bunker Hill Monument in 1843. Not surprisingly, railroad executives and officials were also early users of private railroad cars. Cornelius Vanderbilt, president of the New York Central Railroad, used a private car when traveling over his line, both for business and for pleasure. For a busy railroad manager, the private railcar served as a mobile workspace where business could be conducted at distant points on the railroad line, far from company headquarters.

Pullman cars on the First Transcontinental Railroad, circa 1870. / THF291330

Following the Civil War, the Pullman Palace Car Company earned a reputation for its opulent public passenger cars with comfortable sleeping accommodations. Company founder George Pullman designed a private railcar to similar high standards. Pullman named the car P.P.C.—his company’s initials—and used it when traveling with his family. Pullman enjoyed lending the car to other dignitaries, by which he could simultaneously impress VIP passengers and advertise his company. Eventually, Pullman began renting the car out to patrons who could afford the daily rate of $85 (more than $2,000 today).

Clara and Henry Ford ordered their private railroad car from the Pullman Company on February 18, 1920. They hoped to have it delivered by that September, for a planned trip to inspect properties Henry had recently purchased in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. But delays pushed the car’s actual delivery date back by about nine months. Some of those delays were due to changes to the car’s interior. Clara designed the interior spaces, working with Sidney Houghton of London, who had earlier provided the same service for the Fords’ yacht.

The finished railroad car was delivered on June 23, 1921. The Fords named it Fair Lane—the same name they’d given to their estate in Dearborn, Michigan. (Fair Lane was the area in County Cork, Ireland, where Mr. Ford’s grandfather was born.) The final bill for the railcar came to $159,000 (about $2.3 million today). The Fords paid 25 percent of that cost upon placing their order, a further 25 percent during construction, and the final 50 percent on delivery.

Surely the finished Fair Lane was worth the wait and expense. The car included accommodations for six passengers and sleeping quarters for two additional staff members. When traveling, Fair Lane typically was staffed by a porter to attend to the passengers’ needs and a cook to prepare meals.

Fair Lane’s lounge offered the best views of passing scenery. / THF186264

At the rear of the car, a comfortable lounge provided a spot to read, relax, or simply watch the passing scenery through the large windows. An open porch-like platform at the very rear of the car was particularly enjoyable at moderate train speeds. Typically, Fair Lane was coupled to the end of a train, meaning that the view from the platform would not be obstructed.

Bedrooms in Fair Lane were cozy but comfortable. / THF186273

From the lounge, a narrow hallway ran most of the car’s length. Four bedrooms were located along the corridor. These rooms were cozy but comfortable. Each room had a bed, but berths could be unfolded from above to provide additional sleeping space if needed. Dressers and small desks rounded out the furnishings. Likewise, the bathrooms in Fair Lane were small but serviceable. Each one had hot and cold running water and a toilet. The master bath also included a shower.

Fair Lane’s passengers dined in this area. An on-board cook prepared meals to order. / THF186285

The dining area, near the front of the car, featured an extension table that comfortably seated six adults at one time. The chandelier, which hung directly above the table, was secured with guys that kept it from swaying as the car rolled down the railroad track. Built-in cabinets housed the car’s glassware and china. Clara Ford stocked Fair Lane with 144 various glasses, 169 pieces of silverware, and 230 crockery items. Wood posts and rails kept things from sliding around or falling out of the cabinets.

The car’s kitchen was small but sufficient for elaborate meals. / THF186289

Logically, the kitchen was located just in front of the dining room. Finished in stainless steel, the kitchen included an oven, a stovetop, a sink, and numerous additional cabinets. Food and supplies were loaded through the door at the car’s front end, so as not to disturb the riders farther back in the car. Staff quarters were located in the front of the car too. Compared with the other bedrooms, the staff room was sparse and utilitarian.

Using Fair Lane was not like driving a limousine or flying a private airplane. The railcar’s travels had to be coordinated with the various host railroads that operated America’s 250,000-mile rail network. Usually, Fair Lane was coupled to a regularly scheduled passenger train. The fee for pulling the private car was equivalent to 25 standard passenger tickets. One standard ticket on a train from Detroit to New York City in the early 1920s cost around $30, meaning the Fair Lane fee worked out to about $750 (around $10,000 today). If Fair Lane required a special movement—that is, if it was moved with a dedicated locomotive and not as a part of a regular train—then the fee jumped to the equivalent of 125 standard tickets.

The fee structure was different when Fair Lane moved over the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railroad. Henry Ford personally owned DT&I from 1920 to 1929. It was considered official railroad business when Mr. Ford used his private car on DT&I, so he did not need to pay a fare for himself. But he did pay fares for Fair Lane passengers who weren’t directly employed by DT&I.

Edsel and Eleanor Ford, Henry and Clara Ford, and Mina and Thomas Edison pose on the car’s rear platform about 1923. / THF97966

The Fords made more than 400 trips with Fair Lane in the two decades that they owned the car. Annual excursions took Henry and Clara Ford to their winter homes in Fort Myers, Florida, or Richmond Hill, Georgia. Likewise, Edsel and Eleanor Ford, Henry and Clara’s son and daughter-in-law, occasionally used Fair Lane to visit their own vacation home in Seal Harbor, Maine. The Fords hosted several special guests on the car too. Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge both spent time on the car, as did entertainer and humorist Will Rogers. Not surprisingly, Thomas and Mina Edison—among Henry and Clara Ford’s closest friends—also traveled aboard Fair Lane.

Clara Ford enjoyed trips to New York City, where she could visit friends or patronize specialty boutiques and department stores. Fair Lane could be coupled to direct Detroit–New York trains like New York Central’s Wolverine or Detroiter. Both trains arrived at the famous Grand Central Terminal in the heart of Manhattan. In 1922, an overnight run from the Motor City to the Big Apple on the Wolverine took 16 hours.

Both Henry Ford and Edsel Ford used Fair Lane when traveling on Ford Motor Company business. Chicago, New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C., were all frequent destinations on these trips. Of course, they’d travel to distant Ford Motor Company properties too, including those previously mentioned holdings in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Detroit’s Michigan Central Station, where most of Fair Lane’s journeys began and ended. / THF137923

Most of the car’s trips started and ended at Detroit’s Michigan Central Station, ten miles east of Dearborn. The large station had facilities to clean and stock Fair Lane, and crews to switch the car onto regular passenger trains. Michigan Central was a New York Central subsidiary, and New York Central trains provided direct service from Detroit to Chicago, New York, Boston, and many places in between. For longer trips, New York Central coordinated with additional railroad lines to transfer Fair Lane to other trains at connecting points, making the trip as seamless as possible for the Fords.

When Fair Lane wasn’t traveling out on a railroad, the car was stored in a shed built for it near Henry Ford’s flour mill on Oakwood Boulevard in Dearborn. The shed was just west of Dearborn’s present John D. Dingell Transit Center, where Amtrak trains stop today.

The Fords considered updating or replacing Fair Lane at different times. As early as March 1923, Ernest Liebold, Henry Ford’s personal secretary, wrote to the Pullman Company to inquire about building a larger car surpassing Fair Lane’s 82-foot length. Whatever Pullman’s reply, Ford did not place a new order. Twelve years later, Edsel Ford wrote to Pullman to ask about adding air conditioning to Fair Lane. The company responded with an estimate of $12,000 for the upgrade. Apparently, the cost was high enough for the Fords to once again consider building an entirely new, larger private railcar. The Pullman Company prepared a set of drawings for review but, once again, no order was placed.

Fair Lane in November 1942, at the end of its time with the Fords. / THF148020

By the early 1940s, Fair Lane was aging and in need of either significant repairs or outright replacement. Henry and Clara Ford were aging too, and weren’t traveling quite as much as they had in earlier years. On top of this, the United States joined World War II following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Wartime brought with it restrictions on materials, manufacturing, and travel—each on its own enough to sidetrack further work on Fair Lane. Somewhat reluctantly, Henry and Clara Ford sold their private railroad car in November 1942.

The St. Louis Southwestern Railway purchased Fair Lane from the Fords for $25,000. The company used the car for railroad business, carrying executives on its lines concentrated in Arkansas and Texas. In 1972, St. Louis Southwestern donated Fair Lane to the Cherokee National Historical Society. The organization used the car as an office space for the Cherokee Nation in Tahlequah, Oklahoma.

Richard and Linda Kughn purchased Fair Lane in 1982. They moved it to Tucson, Arizona, and began a four-year project to restore the car to its original Ford-era appearance. At the same time, they updated Fair Lane with modern mechanical, electrical, and climate-control systems. The Kughns enjoyed the refurbished railcar for several years before gifting it to The Henry Ford in 1996. Today Fair Lane is back in Dearborn—a testament to the golden age of railroad travel, as experienced by those with gilded budgets.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- 1924 Railroad Refrigerator Car, Used by Fruit Growers Express

- Ingersoll-Rand Number 90 Diesel-Electric Locomotive, 1926

- Allegheny Locomotive: Can-Do Experience

- Revolution on Rails: Refrigerated Box Cars

21st century, 20th century, travel, railroads, Michigan, Henry Ford Museum, Henry Ford, Fair Lane railcar, Detroit, Dearborn, Clara Ford, by Matt Anderson

Interior of Henry Ford’s Private Railroad Car, “Fair Lane,” June 22, 1921 / THF148015

Beginning in 1921, Henry and Clara Ford used their own railroad car, the Fair Lane, to travel in privacy. Clara Ford designed the interior in consultation with Sidney Houghton, an interior designer based in London. The interior guaranteed a comfortable trip for the Fords, their family, and others who accompanied them on more than 400 trips between 1921 and 1942.

The view out the railcar windows often featured the landscape between Dearborn, Michigan, and Richmond Hill, Georgia, located near Savannah. The Fords purchased more than 85,000 acres in the area, starting in 1925, remaking it into their southern retreat.

On at least three occasions, Henry Ford might have looked out that Fair Lane window, observing changes in the landscape between Richmond Hill and a siding (or short track near the main railroad tracks, where engines and cars can be parked when not in use) near Tuskegee, Alabama. Henry Ford took the railcar to the Tuskegee Institute in 1938, 1941, and 1942, and Clara accompanied Henry at least twice.

Henry Ford and George Washington Carver, Tuskegee, Alabama, March 1938 / THF213839

Henry first met with George Washington Carver and Austin W. Curtis at Tuskegee on March 11, 1938. A small entourage accompanied him, including Ford’s personal secretary, Frank Campsall, and Wilbur M. Donaldson, a recent graduate of Ford’s school in Greenfield Village and student of engineering at Ford Motor Company.

George Washington Carver and Henry Ford on the Tuskegee Institute Campus, 1938. / THF213773

Photographs show these men viewing exhibits in the Carver Museum, installed at the time on the third floor of the library building on the Tuskegee campus (though it would soon move).

Austin Curtis, George Washington Carver, Henry Ford, Wilbur Donaldson, and Frank Campsall Inspect Peanut Oil, Tuskegee Institute, March 1938 / THF 213794

Frank Campsall, Austin Curtis, Henry Ford, and George Washington Carver at Tuskegee Institute, March 1938 / THF214101

Clara accompanied Henry on her first trip to Tuskegee Institute, in the comfort of the Fair Lane, in March 1941. Tuskegee president F.D. Patterson met them at the railway siding in Chehaw, Alabama, and drove them to Tuskegee. While Henry visited with Carver, Clara received a tour of the girls’ industrial building and the home economics department.

During this visit, the Fords helped dedicate the George W. Carver Museum, which had moved to a new space on campus. The relocated museum and the Carver laboratory both occupied the rehabilitated Laundry Building, next to Dorothy Hall, where Carver lived. A bust of Carver—sculpted by Steffen Thomas, installed on a pink marble slab, and dedicated in June 1937—stood outside this building.

The dedication included a ceremony that featured Clara and Henry Ford inscribing their names into a block of concrete seeded with plastic car parts. The Chicago Defender, one of the nation’s most influential Black newspapers, reported on the visit in its March 22, 1941, issue. That story itemized the car parts, all made from soybeans and soy fiber, that were incorporated—including a glove compartment door, distributor cap, gearshift knob, and horn button. These items symbolized an interest shared between Carver and Ford: seeking new uses for agricultural commodities.

Clara Ford, face obscured by her hat, inscribes her name in a block of concrete during the dedication of George Washington Carver Museum, March 1941, Tuskegee Institute, Alabama. Others in the photograph, left to right: George Washington Carver; Carrie J. Gleed, director of the Home Economics Department; Catherine Elizabeth Moton Patterson, daughter of Robert R. Moton (the second Tuskegee president) and wife of Frederick Douglass Patterson (the third Tuskegee president); Dr. Frederick Douglass Patterson; Austin W. Curtis, Jr.; an unidentified Tuskegee student who assisted with the ceremony; and Henry Ford. / THF213788

Henry Ford inscribing his name in a block of cement during the dedication of George Washington Carver Museum, Tuskegee Institute, March 1941 / THF213790

After the dedication, the Fords ate lunch in the dining room at Dorothy Hall, the building where Carver had his apartment, and toured the veterans’ hospital. They then returned to the Fair Lane railcar and headed for the main rail line in Atlanta for the rest of their journey north.

President Patterson directed a thank you letter to Henry Ford, dated March 14, 1941. In this letter, he commended Clara Ford for her “graciousness” and “her genuine interest in arts and crafts for women, particularly the weaving, [which] was a source of great encouragement to the members of that department.”

The last visit the Fords made to Tuskegee occurred in March 1942. The Fair Lane switched off at Chehaw, where Austin W. Curtis, Jr., met the Fords and drove them to Tuskegee via the grounds of the U.S. Veterans’ Hospital. Catherine Patterson and Clara Ford toured the Home Economics building and the work rooms where faculty taught women’s industries. Clara rode in the elevator that Henry had funded and had installed in Dorothy Hall in 1941, at a cost of $1,542.73, to ease Carver’s climb up the stairs to his apartment.

The Fords dined on a special luncheon menu featuring sandwiches with wild vegetable filling, prepared from one of Carver’s recipes. They topped the meal off with a layer cake made from powdered sweet potato, pecans, and peanuts that Carver prepared.

Tuskegee shared the Fords’ itinerary with Black newspapers, and the April 20, 1942, issue of Atlanta Daily World carried the news, “Carver Serves Ford New Food Products.” They concluded, in the tradition of social columns at the time, by describing what Henry and Clara Ford wore during the visit. “Mrs. Ford wore a black dress, black hat and gloves and a red cape with self-embroidery. Mr. Ford wore as usual an inconspicuously tailored business suit.”

Dr. Patterson wrote to Henry Ford on March 23, 1942, extending his regrets for not being at Tuskegee to greet the Fords. Patterson also reiterated thanks for “Mrs. Ford’s interest in Tuskegee Institute”—“The people in the School of Home Economics are always delighted and greatly encouraged with the interest she takes in the weaving and self-help project in the department.”

The Fords sold the Fair Lane in 1942. After many more miles on the rails with new owners over the next few decades, the Fair Lane came home to The Henry Ford. Extensive restoration returned its appearance to that envisioned by Clara Ford and implemented to ensure comfort for Henry and Clara and their traveling companions. Now the view from those windows features other artifacts on the floor of the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, in place of the varied landscapes, including those around the Tuskegee Institute, traveled by the Fords.

A view of the interior of Henry and Clara Ford’s private railroad car, the “Fair Lane,” constructed by the Pullman Company in 1921, restored by The Henry Ford to that era of elegance, and displayed in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF186264

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

1940s, 1930s, 20th century, Alabama, women's history, travel, railroads, Henry Ford Museum, Henry Ford, George Washington Carver, Ford family, Fair Lane railcar, education, Clara Ford, by Debra A. Reid, African American history

You could argue that one of the most visible buildings in Greenfield Village is Martha-Mary Chapel, standing as it does at the end of the Village Green, with its columns in front and high steeple. However, unlike many of the other buildings in the Village, the Chapel is not a historic building that was moved from elsewhere, but was built in the Village in 1929. Henry Ford wanted to recreate a typical village green and therefore had the Chapel (a characteristic building for a green) built, and named it after both his own mother, Mary Litogot Ford, and his wife Clara’s mother, Martha Bench Bryant. Some of the fixtures on the building came from Clara Ford’s childhood home, adding another layer of personal resonance. We’ve just digitized more than 100 images of the Chapel taken over its nearly 90-year history, including this classic shot from 1935—browse them all by visiting our Digital Collections.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Clara Ford, Henry Ford, Ford family, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl

Cooking with Clara Ford

Clara Ford reminiscing over her first cookbook, the Buckeye Cookbook, at the Women’s City Club, 1949

“I don’t think Mrs. Ford had any outstanding hobby outside her gardening, except possibly recipes” – Rosa Buhler, maid at Fair Lane.

Clara certainly seemed to enjoy her recipes, from Sweet Potato Pudding to Corned Tongue, Clara collected hundreds of recipes. Some were in the form of cookbooks, some typed up, others cut out of magazines or newspapers, but the majority of them were handwritten, either by Clara or the many friends she gathered recipes from.

By the time the Fords moved to Fair Lane, Clara probably wasn’t cooking much from the Buckeye Cookbook her mother gave her when she married as the household staff now included a cook, but Clara never stopped searching out new recipes to try. According to Buhler, “Mrs. Ford would come down every day to talk over the day’s menu. She always saved recipes from cookbooks or the newspaper.” Clara was also very particular about her food, which led to a high turnover in cooks, so when there wasn’t a cook the other servants had to prepare the meals. John Williams, the Fair Lane houseman (and occasional cook) remarked that “Mrs. Ford had a lot of good cookbooks. Sometimes when I was in the kitchen, she would come out and say, ‘John, I found a good recipe. Sometime we’ll try it.’” Everywhere she went, Clara would pay close attention to the food and would frequently ask hostesses for their recipes. Buhler remembered when the Fords would visit Georgia, “every once in a while they’d spring something new on her in the way of Southern cooking. That intrigued her, and she’d ask about it. She’d probably get the recipe from the lady who served it, and she’d want her cook to try it.” There’s plenty of correspondence between Clara and her friends and acquaintances swapping recipes and menu ideas. Clara responded to one such letter from Charlotte Copeland which included a recipe for “Tongue en Casserole” saying, “thank you so much. I do love recipes from friends that have tried them,” and reciprocated with a recipe of her own. In her collection are recipes from Mrs. Ernest Liebold (wife of Henry Ford’s secretary), Mrs. Gaston Plantiff (wife of another Ford associate), and there’s even a recipe for “Mr. Burroughs’ Brigand Stake” (possibly from the famous Vagabond naturalist himself).

While Henry preferred very plain foods, Clara liked richer fare; cream sauces, butter, and lots of spices. She also preferred the traditional English cuisine and style of cooking of her mother’s family. Not a few of the servants questioned the wisdom of the English methods, and as noted above many cooks came and went at Fair Lane. Buhler said that, “Mrs. Ford stuck to the old-fashioned ways, for instance, plum pudding for Christmas. We always had to have it cooked in a cloth and though it always turned out to be a failure, the very next Christmas we had to do the very same thing over.” Not all the traditional recipes resulted in less than satisfactory results however, John Williams spoke of one particular recipe he became expert at, “Mrs. Ford had a favorite recipe that she taught me how to make. It was her mother’s recipe. The crust was made with sour cream, salt and soda, and the apples were sliced and put in a pie plate. This crust was spread over the top very thinly which made it very light….After it was baked, you would turn it on a platter that it was to be served on, and then you would add your sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg after it was cooked. It made a very delicious pie. Any time any cook was hired, I would have to show them that recipe,” though he did say “In my way of thinking, you could make a two-crust pie much quicker than you could make this.”

While Henry preferred very plain foods, Clara liked richer fare; cream sauces, butter, and lots of spices. She also preferred the traditional English cuisine and style of cooking of her mother’s family. Not a few of the servants questioned the wisdom of the English methods, and as noted above many cooks came and went at Fair Lane. Buhler said that, “Mrs. Ford stuck to the old-fashioned ways, for instance, plum pudding for Christmas. We always had to have it cooked in a cloth and though it always turned out to be a failure, the very next Christmas we had to do the very same thing over.” Not all the traditional recipes resulted in less than satisfactory results however, John Williams spoke of one particular recipe he became expert at, “Mrs. Ford had a favorite recipe that she taught me how to make. It was her mother’s recipe. The crust was made with sour cream, salt and soda, and the apples were sliced and put in a pie plate. This crust was spread over the top very thinly which made it very light….After it was baked, you would turn it on a platter that it was to be served on, and then you would add your sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg after it was cooked. It made a very delicious pie. Any time any cook was hired, I would have to show them that recipe,” though he did say “In my way of thinking, you could make a two-crust pie much quicker than you could make this.”

- Clara appears to have had a sweet tooth, the majority of the recipes fall into the dessert category. A variety of cakes, cookies, puddings, and pies appear in her collection with flavors from chocolate and butterscotch to blackberry. Many of the entrees and sides were vegetarian, reflecting on Henry’s preferences for lighter fare and Clara’s love of gardening, there were even recipes for alcoholic beverages (something Henry hardly ever consumed). In all there are recipes ranging from Green Mango Pie and Blueberry Dumplings, to Suet Pudding and Frizzled Oysters. If you’re looking to “Coddle an Egg” or find a recipe “For Crusty Top to Soufflé” Clara Ford has a recipe in her collection for you. The only ingredient that seems to be notable for its lack of representation in the collection is the soybean, only one recipe “25% Soybean Bread” features Henry’s favorite legume. John Thompson, butler at Fair Lane noted “Mr. Ford tried to convince Mrs. Ford she should have an interest in soybean products, but she never did. She never thought much of them...Mr. Ford used to eat soybean soup every day during the period he was interested in those experiments…Mrs. Ford didn’t go for this soup.” Though they could both agree on wheat germ, one of their favorite cookies being Model T’s, and according to Ford employee A.G. Wolfe, “You haven’t had anything until you have had a Model T cookie!”

Learn more:

Ford family, Michigan, Dearborn, 20th century, women's history, recipes, making, food, Clara Ford, by Kathy Makas, archives

Clara Ford’s Roadside Market: A Small Building with Big Aspirations

Buying fresh produce direct from local farmers is a key to our efforts today to “eat local.” Nearly 90 years ago, Clara Ford was advocating the same thing, to improve on diets that were undermined by too much processed food and--more importantly to her--to improve the situations of rural farm women. Continue Reading

Michigan, women's history, cars, by Jim McCabe, food, shopping, Clara Ford, agriculture, farms and farming

Jens Jensen (1860–1951) was a Danish-born landscape architect who did a large amount of design work for the Ford family and Ford Motor Company. This included Ford Motor Company pavilion landscaping for the 1933–34 Chicago World’s Fair, landscape design for multiple residences of Edsel Ford, and complete landscaping for Fair Lane, the Dearborn estate of Henry and Clara Ford. We’ve just digitized 29 blueprints from the Jens Jensen Drawings Series showing planting plans, grading and topographical plans, and water feature plans for the Fair Lane estate, such as this one for a bird pool. View all related material in our digital collections.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, Ford family, Clara Ford, home life, 20th century, 1920s, 1910s, Henry Ford, drawings, digital collections, design, by Ellice Engdahl

"The Call of The Wild" at The Henry Ford

In 1903, Jack London was a young writer still in the early stages of his career. He was 27 years old when he published The Call of the Wild, the story that was destined to become an American classic and earn him a place in the canon of American literature. Drawing upon London’s experiences in the Klondike Gold Rush, The Call of the Wild is the story of Buck, a dog who is kidnapped from his idyllic home in northern California and thrown into the harsh life of a sled dog in the cold wilderness of the Yukon.

The Call of the Wild was first published in The Saturday Evening Post, a popular weekly magazine that featured a variety of content including articles on current events, editorials, illustrations, cartoons, poetry, and fiction. The magazine paid Jack London a sum of $750 for his story, the equivalent of almost $20,000 today. The Call of the Wild was published in five consecutive issues from June 20, 1903 to July 18, 1903. The first two of these issues are held in the collections of The Henry Ford, including the initial issue which features The Call of the Wild on the cover.

The Saturday Evening Post had widespread circulation; in fact, even Clara Ford had a subscription. Several of The Henry Ford’s issues from around 1903 bear an address label for Mrs. H. Ford at 332 Hendrie Ave., the address of the Fords’ residence in Detroit at the time. Henry Ford founded Ford Motor Company on June 16, 1903, just four days before The Call of the Wild was first published. When the final installment of The Call of the Wild was published a month later, Ford Motor Company had just sold their first car for $850, as recorded in their first checkbook. Coincidentally, the base price of the Model A car was $750, the same amount that Jack London received from The Saturday Evening Post for his story. (Ford Motor Company’s first customer paid an extra $100 for a tonneau, or backseat compartment, bringing the total for the car to $850.) I imagine that Henry Ford was quite busy building his fledgling company and didn’t have much time for leisure reading. However, it is interesting to think that he or his wife Clara might have read The Call of the Wild when it was first published, especially at a time when both Henry Ford and Jack London were on the verge of success that would lead them to become icons in American industrial and literary history, respectively.

The Saturday Evening Post had widespread circulation; in fact, even Clara Ford had a subscription. Several of The Henry Ford’s issues from around 1903 bear an address label for Mrs. H. Ford at 332 Hendrie Ave., the address of the Fords’ residence in Detroit at the time. Henry Ford founded Ford Motor Company on June 16, 1903, just four days before The Call of the Wild was first published. When the final installment of The Call of the Wild was published a month later, Ford Motor Company had just sold their first car for $850, as recorded in their first checkbook. Coincidentally, the base price of the Model A car was $750, the same amount that Jack London received from The Saturday Evening Post for his story. (Ford Motor Company’s first customer paid an extra $100 for a tonneau, or backseat compartment, bringing the total for the car to $850.) I imagine that Henry Ford was quite busy building his fledgling company and didn’t have much time for leisure reading. However, it is interesting to think that he or his wife Clara might have read The Call of the Wild when it was first published, especially at a time when both Henry Ford and Jack London were on the verge of success that would lead them to become icons in American industrial and literary history, respectively.