Posts Tagged dearborn

The Logan County Courthouse, a fixture on the Village Green in Greenfield Village, will has reached the milestone of having been here in Dearborn for as many years as it was in Postville, Illinois - 89 years.

Abraham Lincoln featured prominently in Henry Ford’s plans for Greenfield Village, which revolved around the story of how everyday people with humble beginnings would go on to play important roles in American history. Lincoln epitomized Ford’s view of the “self-made man,” and he made a significant effort to collect as many objects as possible associated with him. By the late 1920s, Henry Ford was a “later comer” to the Lincoln collecting world, but with significant resources at his disposal, he did manage to secure a few very important items. The Logan County Courthouse is among them.

It has taken nearly all the 89 years to achieve this, but an original feature, long absent from the courtroom is making a return. The bar now stands again. Using the original set of spindles, we have re-created our interpretation of what the rail, or the bar, that divided the courtroom may have looked like in the1840s. By referencing images of other early 19th century courtrooms, and studying architectural features represented in Greenfield Village, a typical design was created.

The stories associated with the Logan County Courthouse are fascinating. As it turns out, the story of how the original spindles from the original bar finally made their way back into the courthouse is fascinating as well.

Authenticated objects, related to Lincoln’s early life, were especially scarce by the late 1920s. There seemed to be an abundance of items supposedly associated and attributed to Lincoln, especially split rails and things made from them, but very few of these were the real thing. For Ford, the idea of acquiring an actual building directly tied to Lincoln seemed unlikely.

But, by the summer of 1929, through a local connection, Ford was made aware that the old 1840 Postville/Logan County, Illinois courthouse, where Lincoln practiced law, was available for sale. The 89-year-old building was used as a rented private dwelling, and was in very run-down condition, described by some as “derelict.” It was owned by the elderly Judge Timothy Beach and his wife. They were fully aware of the building’s storied history, and had made several unsuccessful attempts to turn the historic building over to Logan County in return for taking over the care of the building. Seeing no other options, the Beaches agreed to the sale of the building to Ford via one of his agents. They initially seemed unaware of Ford’s intentions to move the building to Greenfield Village, assuming it was to be restored on-site much like another historic properties Ford had taken over. This image shows the state of the building when it was first seen by Henry Ford’s staff in late August of 1929. Not visible in the large shed attached to the rear of the building. THF238386

This image shows the state of the building when it was first seen by Henry Ford’s staff in late August of 1929. Not visible in the large shed attached to the rear of the building. THF238386

The local newspaper, The Courier, even quoted Mrs. Beach as stating that, “she would refund to Mr. Ford if it was his plan to take the building away from Lincoln, as nothing was said by the agent about removal”. By late August of 1929, the entire project in West Lincoln, Illinois, had captured the national spotlight and the old courthouse suddenly had garnered a huge amount of attention, even becoming a tourist destination. By early September, local resistance to its removal was growing, and Ford felt the need to pay a visit to personally inspect the building and meet with local officials, and the Beaches. He clearly made his case with the owners and finalized the deal. As reported, “Ford sympathized with the sentiment of the community but thought that the citizens should look at the matter from a broader viewpoint. He spoke for the cooperation of the community with him in making a perpetual memorial for the town at Dearborn, where the world would witness it. My only desire is to square my own conscience with what I think will be for the greatest good to the greatest number of people."

Henry had made his case and the courthouse would indeed be leaving West Lincoln. Immediately following the final negotiations, Henry Ford’s crew arrived to begin the process of study, dismantling, and packing for the trip to Dearborn. Local resistance to the move continued as the final paperwork was filed to purchase the land. By September 11, the resistance had run its course and the dismantling process began. It was also revealed that the city, county, several local organizations, and even the state of Illinois had all been offered several opportunities to acquire the building and take actions to preserve it. They all had declined the various offers over the years. It was then understood that Judge & Mrs. Beach, in the end, had acted on what was best for the historic building and should not be “subjected to criticism.” Judge Beach would die on September 19, just as the last bits of the old courthouse were being loaded for their journey to Greenfield Village.

Reconstruction, which included the fabrication of many of the first-floor details and a new stone chimney and fireplaces, began immediately. In roughly a month’s time, the building was ready for the grand opening of Greenfield Village on October 21, 1929.

Nine years later, in 1938, Eugene Amberg sent a letter to Ford describing an interesting discovery. Mr. Amberg was a native of what was now Lincoln, Illinois and worked as a railroad ticket agent. He had a great interest in the local history and was a collector of local artifacts. As he writes in the letter dated February 8, 1938:

Several years ago, you purchased the Old Postville Court House here in Lincoln, Ills from Mrs. T Beach. At the time the Court House was made into a dwelling the railing that separated the judges desk from the main court room was torn out by my father (John Amberg) who was doing the remodeling, this he stored in the attic of his home, recently my mother died and while cleaning out the attic we came across these spindles, which are the original 28 spindles that the hand railing rested upon. The hand railing was of walnut, out of which was carved some arm rests that are now on some of the pews in St. Mary’s, a church here.

Would appreciate a line from you as to whether or not you would be interested in these spindles, have had numerous offers for them, inasmuch as they are part of the original court house I feel they should be with it, in your Dearborn Village.

Dated February 7, 1938, this is the initial letter from Gene Amberg to Henry Ford offering the 28 original spindles for sale. Despite several letters back and forth, a price could not be settled upon, and the transaction never took place. THF288006

This drawing was sent by Gene Amberg, as a follow-up to his first letter offering the spindles for sale. The artist, Mary Katherine, was Gene’s 14 year old daughter. THF288012

Negotiations evidently faltered, as a price was not agreed upon, and the spindles were never sent. Fast forward 71 years to 2009 when an email arrived from Carol Moore and her brother, Dennis Cunningham, the grandchildren of Eugene Amberg. They had no idea that their grandfather had begun this process, and were amazed when we produced the original correspondence from our archival collection. As it turns out, their story was almost identical to Eugene’s. As Carol wrote their mother, “Patricia Amberg Cunningham died March 1, 2008. While cleaning her house in Delavan, Illinois to prepare for sale, we found 28 old wooden spindles and a newspaper article believed to be from the Lincoln Courier indicating that the spindles are from the original Postville Courthouse in Lincoln, Illinois. It is our desire to donate them to the original Postville Courthouse.”

She was very familiar with Greenfield Village, and had visited the courthouse here. Jim McCabe, the Buildings Curator at the time, gladly accepted the donation.

Clipping from the Lincoln Courier ca. 1934, noting the 28 spindles from the “old Postville courthouse” in the possession of Gene Amberg. THF288016, THF288017

In 1848, the county seat moved from Postville, to Mount Pulaski. At that time the courthouse was decommissioned, and the county offices moved to a new courthouse. After a legal battle between the County, and the original investor/builders of the building, it was sold to Solomon Kahn. None other than Abraham Lincoln successfully represented the County in the matter.

Understanding the local history helps to also understand the changes that took place to the building. It explains how and why portions of the building were altered, parts removed, and eventually separated.

By the late 1840s, changes had taken place on both the exterior and interior. The most significant of these was the move off its original foundation, 86 feet forward on the lot. Mr. Kahn converted the building into a general store, and ran the local post office. It was he who moved the building to its new location. In doing so, it was lifted off its original limestone foundation, and the original single limestone chimney and interior fireplaces were demolished. A new brick lined cellar and foundation were created, along with updated internal brick chimneys on each end of the building, designed to accommodate cast-iron heating stoves.

This is the earliest known photograph of the Logan County Courthouse taken some time between 1850 and 1880. This photograph shows the building in its second location, 80 feet forward from its original foundation, at the crest of a small rise. The original window and door configuration remain intact. The original single stone chimney, now restored to the left side of the building, has been replaced by two internal brick chimneys designed for cast-iron heating stoves. Though not visible in the photograph, the building now sits on a new brick foundation and cellar. The items sitting near the doorway speak to the building’s new life as a store. THF132074

By 1880, the old courthouse had been converted from a commercial building into a private dwelling, and that was the state in which it was found by Ford’s crew in 1929. The doorway and first floor interior had been radically changed. Later, a porch was added to the front entrance, and a shed addition was added to the rear. Photographs taken in September of 1929 during the dismantling, show the outline of the original chimney on the side of the building where it has been re-created today. Further discoveries revealed the original floor plan of a large single room on the first-floor, and the original framing for the room divisions on the second. Second floor photographs show the original wall studs, baseboards, chair rails, window, and door frames, all directly attached to the framing, with lath and plaster added after the fact. The framing of the walls on the first floor were all clearly added after the original build.

This post 1880 view of the Logan County Courthouse shows its transformation into a two- family dwelling. Note the single doorway is now two, the second now taking the place of a former window opening. THF238350

This image shows further remodeling of the front of the building. This photo ca.1900 shows the addition of recessed covered porch with some decorative posts and millwork. This is the iteration in which the building was found when it was sold to Henry Ford in September of 1929. THF238348

These three images show the re-modeled interior of what was the original courtroom, now serving as the kitchen, dining room, and parlor. These photos were taken by Henry Ford’s staff just prior to the dismantling of the building in September of 1929. THF238580

The sub-divided first floor courtroom. THF238600

View of the cellar entrance under the stairway in the sub-divided courtroom. THF238598

We have no evidence that tells us what if any interior changes Mr. Kahn may have made when he relocated the building around 1850. The earliest photograph we have of the building shows it in its new location, but except for its new brick chimneys, it retains what appears to be its original door and window configuration. We can only assume that Mr. Kahn had kept the rail in place, which may have proved useful in the building’s new configuration as a store and post office. No photographs of the original courtroom exist and extensive changes made first in 1880, and then when the building was dismantled and reconstructed in Greenfield Village, further comprised any original evidence.

This view of the dismantled second floor shows matching trim and chair rail connected directly to the studs indicating this as the originally installed woodwork from 1840. The wall partition studs are also notched to meet the ceiling joists, showing that they are also part of the original framing configuration of the second floor. All the trim work, including the doors were made of walnut. THF285571

Based on the evidence we do have about these changes, it is very likely that at the time of the building’s conversion into a private dwelling, around 1880, the decorative hand-turned spindles and walnut hand rail would have been salvaged as the first floor of the building was sub-divided into a duplex. As stated in the family history, the walnut top rail was re-purposed and used in St. Mary’s Catholic Church (which burned in 1976), and the spindles saved for a future project.

Analysis of the original spindles showed that they were poplar, a wood commonly used for turning and as a secondary wood in the mid-19th century. Based on what we knew, we decided to use a combination of woods for the reconstruction of the bar rail. Walnut was used for the top rail and column caps, and the remainder of was done in poplar. Though refinished in 1929, the original walnut trim throughout the building was used as a guide for the color and sheen of the final finish. Reproduction hardware, again based on the existing hardware, mainly on the second floor, was used to mount the center gate.

Mose Nowland, conservation team volunteer at The Henry Ford, works on the design rendering for the bar. (Photo by Jim Johnson)

Mose Nowland and other members of The Henry Ford Conservation Team with the newly installed bar. (Photo by Bill Pagel)

The design of the physical installation of the rail and gate was robust. Each of the support columns is supported within by a steel post that runs through the floor joists and into the cellar floor. With over a half million guests visiting Greenfield Village each year, we thought this important. The design also offers some degree of protection to the original spindles that are centered within the top and bottom rail. This is a permanent installation, and we wanted to be sure it would stand up to the test of time.

Views of the newly re-created bar at the Logan County Courthouse in Greenfield Village. (Photos by Jim Johnson)

A huge thank you to Mary Fahey and Dennis Morrison for stewarding the project. Also to Mose Nowland, our extraordinary volunteer with The Henry Ford’s Conservation Team, who lead the charge in creating the design, and produced beautifully detailed drawings. Ken Gesek, one of our Historic Buildings Carpenters, built the rail, Cuong Nguyen and Tamsen Brown, with the help of the rest of the THF Conservation Team, oversaw the restoration of the original spindles. Tamsen also developed the formula to match the stain and finish to the existing woodwork in the courthouse. Jason Cagle, from the Painting Staff, skillfully applied the finish. Many other people worked to move the project forward as well.

This true team effort resulted in the original spindles finally being reunited with the Logan County Courthouse after an absence of nearly 140 years.

Logan County Courthouse as it appears today in Greenfield Village. (Photo by Jim Johnson)

Jim Johnson is Director of Greenfield Village at The Henry Ford.

Explore more of our Logan County Courthouse artifacts in our digital collections.

Sources Cited

- Fraker, Guy C. Lincoln’s Ladder to the Presidency: The Eighth Judicial Circuit, Carbondale, IL., Southern Illinois University Press, 2012.

- Leigh Henson, Mr. Lincoln, Route 66, and Other Highlights of Illinois, The Postville Courthouse as Private Property, http://findinglincolnillinois.com/sitemap.html

- Lincoln’s Eight Judicial Circuit, http://www.lookingforlinocln.com/8thcircuit/

- Logan County Courthouse Spindle Accession File, 2009.111, items 1-28, Archival Collection of the Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- Logan County Courthouse Building Files including original correspondences, records, photographs prior to dismantling in September of 1929, photographs of dismantling process, September 1929, reconstruction photographs, Greenfield Village, September 1929, 19th century photographic images, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- The Herald, vol. 5 n.3, The Edison Institute Press, March 4, 1938.

- Illinois, Logan County, Postville, 1840 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration

- Illinois, Logan County, Postville, 1850 U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration

- Stringer, Lawrence B, The History of Logan County, Illinois, A Record of its Settlement, Organization, Progress and Achievement, Pioneer Press, Chicago, 1911.

- “The Story of the Purchase of the Logan County Courthouse and its Removal to Greenfield Village by Mr. Henry Ford, as told in the columns of the Lincoln Evening Courier, 8/19/29-10/21/29”, compiled by Thomas I. Starr, Aug 1931. Logan County Courthouse Building Files, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

21st century, 2010s, 19th century, 1840s, Illinois, Michigan, Dearborn, presidents, making, Logan County Courthouse, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, collections care, by Jim Johnson, Abraham Lincoln, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

An Old Car Festival for the Books: 2017

The Canadian Model T Assembly Team wowed Old Car Festival crowds by putting together a working chassis in less than 10 minutes.

Our 67th annual Old Car Festival is in the books – and it was one for the books this year. Postcard-perfect weather, a host of new activities and hundreds of vintage automobiles from motoring’s first decades made this one of the most exciting Greenfield Village car shows in recent memory. This yellow 1921 Lincoln, from the Cleveland History Center, is believed to be the earliest surviving Lincoln motor car.

This yellow 1921 Lincoln, from the Cleveland History Center, is believed to be the earliest surviving Lincoln motor car.

Lincoln took center stage as our featured marque. It was 100 years ago that Henry Leland left Cadillac to form what would become his second automobile company, named for the first president for whom he voted. We had a number of important Lincolns on hand. From The Henry Ford’s own collection was the circa 1917 Liberty V-12 aircraft engine (Lincoln’s first product) and the 1929 Dietrich-bodied convertible. Our friends at the Cleveland History Center’s Crawford Auto-Aviation Collection brought something very special: a 1921 Model 101 believed to be the oldest surviving Lincoln automobile. The earliest cars, like this red 1903 Ford Model A runabout, line up for their turn at Pass-in-Review.

The earliest cars, like this red 1903 Ford Model A runabout, line up for their turn at Pass-in-Review.

Automotive enthusiasts had their pick of activities. There were the cars, of course, spread chronologically throughout the village. There were the Pass-in-Review parades, in which our expert narrators commented on participating vehicles as they drove past the Main Street grandstand. There were the car games, and continuing demonstrations by the Canadian Model T Assembly Team, in Walnut Grove. There were bicycle games near (appropriately enough) Wright Cycle Company. And there were presentations on various auto-related topics in Martha Mary Chapel and the Village Pavilion. Old Car Festival welcomed a few genuinely rare cars in addition to the wonderfully ubiquitous (Ford, Chevrolet, Dodge Brothers) and downright obscure (Crow, Liberty, Norwalk). Rarities this year included a 1913 Bugatti Type 22 race car (said to be the oldest Bugatti in North America) and a 1914 American Underslung touring car (purportedly the last vehicle produced by the company). Staff presenters and show participants alike dressed in period clothing, adding to the show’s atmosphere.

Staff presenters and show participants alike dressed in period clothing, adding to the show’s atmosphere.

But this year, the cars were only the beginning. Greenfield Village hosted activities and historical “vignettes” keyed to each decade represented in the show. Aging Civil War veterans reminisced about Shiloh and Gettysburg at the Grand Army of the Republic encampment. Farther into the village, doughboys and nurses commemorated the centennial of America’s entry into the Great War. Sheiks and Shebas danced the Charleston at the bandstand near Ackley Covered Bridge. Southern blues resonated through the Mattox Home, evocative of the Great Depression’s bleakest years. Perhaps the most popular vignette, though, was the 1910s Ragtime Street Fair occupying the southern end of Washington Boulevard. Great food, games and dancing filled the street, all set to music provided by some of the most talented piano syncopators this side of Scott Joplin. It’s magical when the sun sets and the headlamps turn on, like those on this 1925 Buick Master 6 Touring.

It’s magical when the sun sets and the headlamps turn on, like those on this 1925 Buick Master 6 Touring.

Longtime show participants and visitors will tell you that the highlight comes on Saturday evening. As the sun sets in the late-summer sky, drivers switch on (or fire up) their acetylene, kerosene and electric headlamps for the Gaslight Tour through Greenfield Village. Watching the parade, it’s hard to tell who enjoys it more – the drivers and passengers, or the visitors lined up along the route. This year’s tour was capped by a fireworks display at the end of the night.

It was a special weekend with beautiful automobiles, wonderful entertainment and – most of all – fellowship and fun for those of us who love old cars. Congratulations to the 2017 Old Car Festival Award Winners.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, Old Car Festival, Greenfield Village, events, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson

Seventy-five Years of the George Washington Carver Cabin

This year, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the dedication of the George Washington Carver Memorial in Greenfield Village. There is not a great deal of specific information about this project in the archival collections, but here is what we do know.

Henry Ford’s connections and interest in the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute began as early as 1910 when he contributed to the school’s scholarship fund. At this time, George Washington Carver was the head of the Research and Experimental Station there.

Henry Ford always had interests in agricultural science, and as his empire grew, he became even more focused on using natural resources, especially plants, to maximize industrial production. He was especially interested in plant materials that could be grown locally. Carver has similar interest, but his focus was on improving the lives of southern farmers. His greatest fame was that of a “Food Scientist”, though he was also very well known for developing a variety of cotton that was better suited for the growing conditions in Alabama. Through the decades that followed, connections and correspondences were made, but it would not be until 1937 that the two would meet face to face.

Through the 1930s, work and research began to really ramp up in the Research or Soybean Laboratory in Greenfield Village. Various plants with the potential to produce industrial products were researched, but eventually, the soybean became the focus. Processes that extracted oils and fibers became very sophisticated, and some limited production of soy based car parts did take place in the late 1930s and early 1940s, as a result of the work done there.

In 1935, the Farm Chemurgic Council had its very first meeting in Dearborn. This group, formed to study and encourage better use of renewable resources, would meet annually becoming the National Farm Chemurgic Council. It was at the 1937 meeting, also held in Dearborn, that George Washington Carver, and his assistant, Austin Curtis, were asked to speak. Carver was put up in a suite of rooms at the Dearborn Inn, and it was here that he and Henry Ford were able to meet and discuss their ideas for the first time, face to face. During the visit, Ford entertained Carver at Greenfield Village and gave him the grand tour. Carver was also invited to address the students of the Edison Institute Schools. Carver would write to Ford following the visit, “two of the greatest things that have come into my life have come this year. The first was the meeting with you, and to see the great educational project that you are carrying on in a way that I have never seen demonstrated before.”

It was at some point during the visit that Henry Ford put forth the idea of including a building dedicated to George Washington Carver in Greenfield Village. It seems that he asked Carver about his recollections of his birthplace, and went as far as to ask for descriptions and drawings. Later correspondence from Austin Curtis in November of 1937 confirm Ford’s interest. It was determined by that point that the original building that stood on the farm of Moses Carver in Diamond Point, Missouri had long been demolished. Granting Ford’s request, Curtis would go on to supply suggested dimensions and a sketch, to help guide the project. The cabin was described as fourteen feet by eighteen feet with a nine- foot wall, reaching to fourteen feet at the peak of the roof. It included a chimney made of clay and sticks.

A 1937 rendering of the birthplace of George Washington Carver based on his recollections. No artist is attributed, but it is likely this was drawn by Carver. THF113849

It would not be until the spring of 1942 that the project would get underway. The building, very loosely based on the descriptions provided by Carver, would be constructed adjacent to the Logan County Courthouse. In 1935, the two brick slave quarters from the Hermitage Plantation, had been reconstructed on the other side of the courthouse. The grouping was completed with the addition of the Mattox House (thought to be a white overseers house from Georgia) in 1943. As Edward Cutler, Henry Ford’s architect, would state in a 1955 interview, “we had the slave huts, the Lincoln Courthouse, the George Washington Carver House. The emancipator was in between the slaves and the highly- educated man, It’s a little picture in itself.”

There are no records beyond Henry Ford’s requests for information as to how the final design of the building, that now stands in Greenfield Village, was determined. An invoice and correspondence does appear requesting white pine logs, of specific dimensions, from Ford’s Iron Mountain property. There is also an extensive photo documentation of the construction process in the spring and early summer of 1942.

Foundation being set, spring 1942. THF28591

Beginnings of the framing, Spring 1942. THF285293

Logs in place, roof framing in process, spring 1942. THF285285

Newly Completed George Washington Carver Memorial, Early Summer, 1942. THF285295

In the end, the cabin would resemble less of a hard scrabble slave hut, and more of a 1940s Adirondack style cabin that any of us would be proud to have on some property “up north”. It was fitted out with a sitting room, two small bedrooms (with built in bunks), a bathroom, and a tiny kitchen. It was furnished with pre-civil war antiques and was also equipped with a brick fireplace that included a complete set-up for fireplace cooking. As an interesting tribute to Carver, a project, sponsored by the Boy Scouts of America, provided wood representing trees from all 48 states and the District of Columbia to be used as paneling throughout the cabin. Today, one can still see the names of each wood and state inscribed into the panels.

Plans had initially been made for Carver to come for an extended stay in Dearborn in August of 1942, but those plans changed and he arrived on July 19. This was likely due to Carver’s frail health and bouts of illness. While the memorial was being built, extensive plans were also underway for the conversion of the old Waterworks building on Michigan Avenue, adjacent to Greenfield Village, into a research laboratory for Carver. The unplanned early arrival date forced a massive effort into place to finish the work before Carver arrival. Despite wartime restrictions, three hundred men were assigned to the job and it was finished in about a week’s time.

George Washington Carver would stay for two weeks and during his visit, he was given the “royal” treatment. His visit was covered extensively by the press and he made at least one formal presentation to the student of the Edison Institute at the Martha Mary Chapel. During his stay, he resided at the Dearborn Inn, but on July 21, following the dedication of the laboratory and the memorial in Greenfield Village, just to add another level of authenticity to the cabin, Carver spent the night in it.

George Washington Carver and Henry Ford at the Dedication of the George Washington Carver National Laboratory, July 21, 1942. THF253993

Edsel Ford, George Washington Carver, and Henry Ford, Carver Memorial, July 21, 1942. THF253989

George Washington Carver at fireplace in Carver Memorial, July 21, 1942. THF285303

George Washington Carver seated at the table in Carver Memorial, July 21, 1942. THF285305

Interior views of Carver Memorial, August, 1943. THF285309 and THF285307

The completed George Washington Carver Memorial in Greenfield Village c.1943. THF285299

Beginning in 1938, Carver began to suffer from some serious health issues. Pernicious anemia is often a fatal disease and when first diagnosed, there was not much hope for Carver’s survival. He surprised everyone by responding to the new treatments and gaining back his strength. Henry and Clara visited Tuskegee in 1938 for the first time, later, when Henry Ford heard of Carver’s illness, he sent an elevator to be installed in the laboratory where Carver spent most of his time. Carver would profusely thank Ford, calling it a “life saver”. In 1939, Carver visited the Fords at Richmond Hill and visited the school the Fords had built and named for him there. In 1941, the Fords made another visit to Tuskegee to attend the dedication of the George Washington Carver Museum.

During this time, Carver would suffer relapses, and then rebound, each time surprising his doctors. This likely had much to do with his change in travel plans in the summer of 1942. Following his visit to Dearborn, through the fall, there was regular correspondence to Henry Ford. One of the last, dated December 22, 1942, was a thank you for the pair of shoes made by the Greenfield Village cobbler. Following a fall down some stairs, George Washington Carver died on January 5, 1943, he was seventy-eight years old.

Carver Memorial in its whitewashed iteration, c.1950. THF285299

It was seventy-five years ago, that George Washington Carver made his last trip to Dearborn. His legacy lives on here, and he remains in the excellent company of those everyday Americans such as Thomas Edison, the Wright Brothers, and Henry Ford, who despite very ordinary beginnings, went on to achieve extraordinary things and inspire others. His fame lives on today, and even our elementary school- age guests, know of George Washington Carver and his work with the peanut.

Jim Johnson is Curator of Historic Structures and Landscapes at The Henry Ford.

Sources Cited

- Bryan, Ford, Friends, Family & Forays: Scenes from the Life & Times of Henry Ford, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 2002.

- Edward Cutler Oral Interview, 1955, Archival Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- Collection of correspondences between Henry Ford and George Washington Carver, Frank Campsall, Austin Curtis, 1937-1943, Archival Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- George Washington Carver Memorial Building Boxes, Archival Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- The Herald, August, 1942, The Edison Institute, Dearborn, MI

Dearborn, Michigan, farms and farming, agriculture, Henry Ford, by Jim Johnson, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, George Washington Carver, African American history

Artist in Residence: Herb Babcock

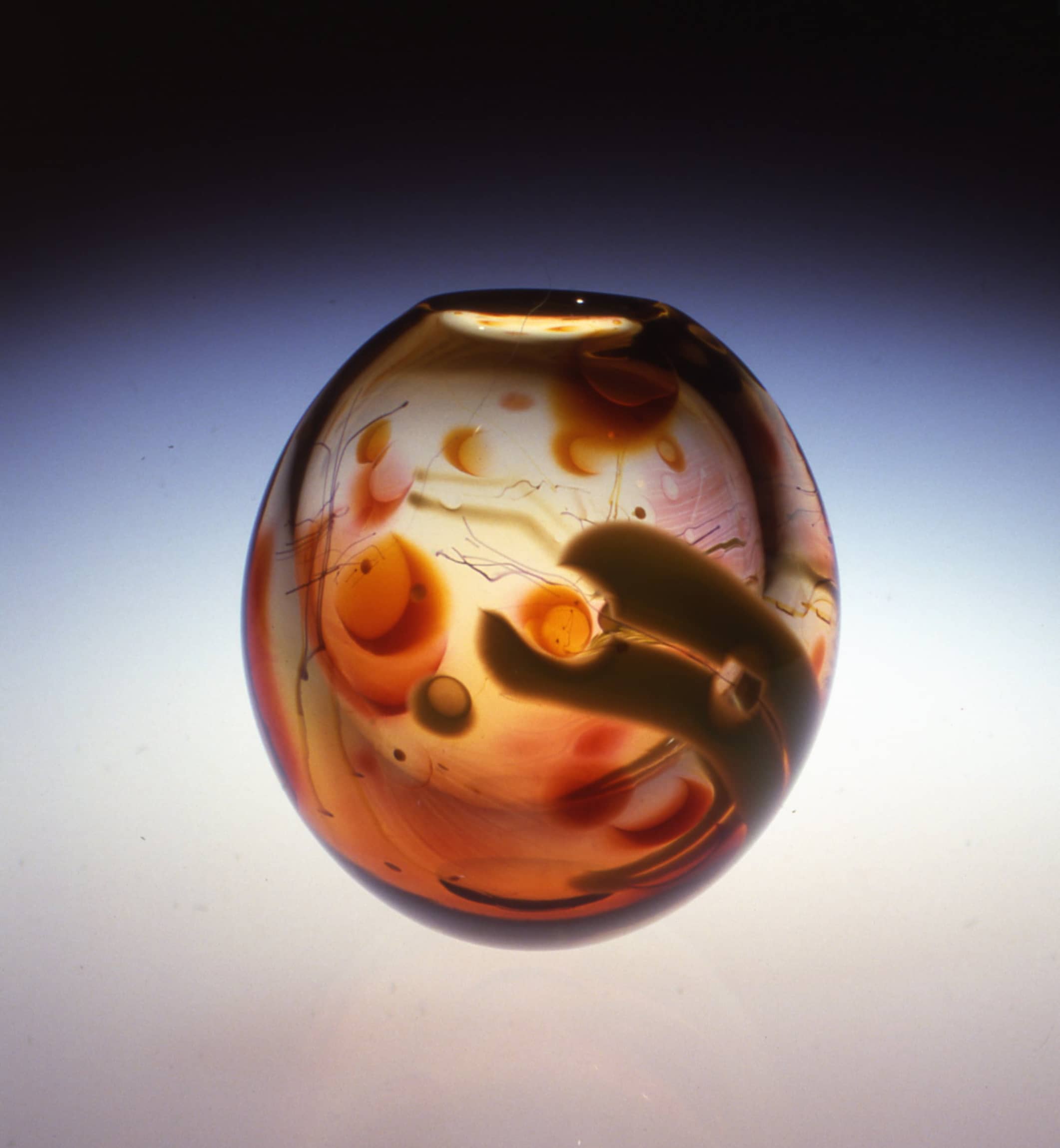

Meet our next artist in residence, Herb Babcock. Tell us a little bit about yourself and your work.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and your work.

I was born in a small town in Ohio in 1946. I received a BFA in Sculpture from the Cleveland Institute of Art, Cleveland, Ohio in 1969 and an MFA in Sculpture from Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan in 1973. I studied sculpture at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine 1967 and glass at the Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio from 1970-71.

I am Professor Emeritus, College for Creative Studies. I taught at CCS for 40 years. Currently I indulge myself in the studio, conceptualizing and creating art.

Fire began to dominate my art in 1969, the first time I tried to blow glass. As a sculptor, I was forging steel into “form.” Molten glass was an alternative: a hot, quick and scary medium to make art. Once I immersed myself in the glass process, the material became a “fine art” medium for me.

As my glass skills evolved and I explored a new process, I created the Image Vessel Series in 1976. In this series, I “painted” using color and line, and “sculpted” to produce a three-dimensional image through a blown-glass vessel.

Do you have a favorite piece you’ve created?

Not one favorite piece; however, each step in the evolution of my work has produced several pieces that I believe interpret what I am trying to say.

Why do you enjoy working with glass?

The three-dimensional world is reflected light and shadow. Glass adds transparency and translucency. Together this considerably expands the vocabulary of sculpture.

Where do you find your inspiration for your creations?

Inspiration comes from the “human figure” along with its movement and stance.

What are you most looking forward to while being an Artist in Residence at The Henry Ford?

I look forward to working with the highly skilled artisans that make up the Henry Ford glass studio. I hope to produce a three- dimensional interpretation of my Image Vessel Series.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 20th century, making, Greenfield Village, glass, artists in residence, art

The Logan County Courthouse Story

As we look forward to the Greenfield Village opening of 2017, our guests and staff alike enjoy reconnecting with our amazing array of historic buildings. Each of them not only represent different periods of American history, they also hold so many fascinating stories. Among the more interesting, are how they came to have new lives here in Greenfield Village. The Logan County Courthouse’s story is among my favorites.

Abraham Lincoln featured prominently in Henry Ford’s plans for Greenfield Village which revolved around the story of how everyday people with humble beginnings would go on to play important roles in American history. Henry Ford was a “later comer” to the Lincoln collecting world, but with significant resources at his disposal, he did manage to secure a few very important items. The Logan County Courthouse is among them. Logan County Courthouse as it stands today in Greenfield Village.

Logan County Courthouse as it stands today in Greenfield Village.

Authenticated objects, related to Lincoln’s early life, were especially scarce by the late 1920s.There seemed to be an abundance of items supposedly associated and attributed to Lincoln, especially split rails and things made from them. But very few of these were the real thing. For Henry Ford, the idea of acquiring an actual building directly tied to Abraham Lincoln seemed unlikely.  Logan County Courthouse September of 1929.

Logan County Courthouse September of 1929.

But, in the summer of 1929, through a local connection, Henry Ford was made aware that the old 1840 Postville/ Logan County, Illinois courthouse, where Lincoln practiced law, was available for sale. The 89-year-old building, was used as a rented private dwelling, and was in run down condition, described by some as “derelict”. It was owned by the elderly Judge Timothy Beach and his wife. They were fully aware of the building’s storied history, and had made several unsuccessful attempts to turn the historic building over to Logan County in return for funding the restoration, and taking over its on-going care and maintenance. View of rear section of building with shed addition, September 1929

View of rear section of building with shed addition, September 1929

Seeing no other options, the Beaches agreed to the sale of the building to Henry Ford via one of his agents. They initially seemed unaware of Henry Ford intentions to move the building to Greenfield Village, assuming it was to be restored on-site much like another historic properties Ford had taken over. The local newspaper, The Courier, even quoted Mrs. Beach as saying “she would refund to Mr. Ford if it was his plan to take the building away from Lincoln, as nothing was said by the agent about removal”. By late August of 1929, the entire project in West Lincoln, Illinois, had captured the national spotlight and the old courthouse suddenly had garnered a huge amount of attention, even becoming a tourist destination.

View of side currently adjacent to Dr. Howard’s Office, September, 1929. This view shows evidence of filled in window openings. The window currently behind the judge’s bench was restored.

View of side currently adjacent to Dr. Howard’s Office, September, 1929. This view shows evidence of filled in window openings. The window currently behind the judge’s bench was restored.

By early September, local resistance to its removal was growing, and Henry Ford felt the need to pay a visit to personally inspect the building and meet with local officials, and the Beaches. He clearly made his case with the owners and finalized the deal. As reported, “Ford sympathized with the sentiment of the community but thought that the citizens should look at the matter from a broader viewpoint. He spoke for the cooperation of the community with him in making a perpetual memorial for the town at Dearborn, where the world would witness it. My only desire is to square my own conscience with what I think will be for the greatest good to the greatest number of people.”

Views of partitioned first floor, summer 1929.

The courthouse would indeed be leaving West Lincoln, and by September 6, Henry Ford’s crew arrived to begin the process of study, dismantling, and packing for the trip to Dearborn. Local resistance to the move continued as the final paperwork was filed, and the newly purchased land was secured by Ford’s staff. By September 11, the resistance had run its course and the dismantling process began. It was also revealed that the city, county, several local organizations, and even the state of Illinois had all been offered several opportunities to acquire the building and take actions to preserve it. They all had declined the various offers over the years. It was then understood that Judge & Mrs. Beach, in the end, had acted on what was best for the historic building and should not be “subjected to criticism.” Judge Beach would die a week later, on September 19th.

The dismantling and discovery process was closely covered by the local newspapers, and as the building came apart, its original design was revealed.

Beginning as early as the late 1840s, changes had taken place on both the exterior and interior of the building. By 1880, the building had been converted from a commercial building into a dwelling and that was the state in which it was found by Ford’s crew in 1929. The doorway and first floor interior had been radically changed and eventually, a covered porch was added to what is now the main entrance, and a shed addition to the rear. But, the most significant change, was the move off its original foundation, 86 feet forward on the lot.

In 1848, the county seat moved from Postville, to Mount Pulaski. At that time the courthouse was decommissioned, and after a legal battle between the County, and the original investor/builders of the building, it was sold to Solomon Kahn. None other than Abraham Lincoln successfully represented the County in the matter. Mr. Kahn converted the building into a general store, and ran the local post office within. It was he who moved the building to its new location. In doing so, the old limestone foundation was left behind, and the original limestone chimney and interior fireplaces were demolished. A new brick lined cellar and foundation was created, along with updated internal brick chimneys on each end of the building, designed to accommodate cast-iron heating stoves. This took place before 1850.

The oldest know photograph of the Logan County Courthouse c.1850-1880. The original door arrangement remains in place.

The oldest know photograph of the Logan County Courthouse c.1850-1880. The original door arrangement remains in place.

Photographs taken in September of 1929, show the outline of the original chimney on the side of the building where it has been re-created today. Further discoveries revealed the original floor plan of a large single room on the first-floor, and the original framing for the room divisions on the second. Second floor photographs show the original wall studs, baseboards, chair rails, window, and door frames, all directly attached to the framing, with lath and plaster added after the fact. The framing of the walls on the first floor were all clearly added after the original build. The oldest photograph of the courthouse shows it on its second site with its original window and door arrangement still in place, but with new brick chimneys. The photo dates from between 1850 and 1880.

It was some of the older inhabitants of the area that alerted Henry Ford’s staff as to the original location of the foundation. Once located, the original foundation revealed the dimensions of the original first-floor fireplace. All the stones were carefully removed and shipped to Dearborn. The courthouse rests on this foundation today. The local newspaper also reported that while excavating the foundation, a large key and doorknob were found at the edge, aligned where the front door would have been located.

View of side that currently faces Scotch Settlement School, September, 1929. Shadow of original stone chimney is visible. Patched sections of siding show that originally, the stone would have been flush with the siding until approximately the top third, which would have extended out from the building like the entire chimney currently does. The window and door are late additions.

View of side that currently faces Scotch Settlement School, September, 1929. Shadow of original stone chimney is visible. Patched sections of siding show that originally, the stone would have been flush with the siding until approximately the top third, which would have extended out from the building like the entire chimney currently does. The window and door are late additions.

By September 20th, the building, consisting of two car loads of material, was on its way to Dearborn. Reconstruction in Greenfield Village began almost immediately at a frenzied pace. Finishing touches were still being applied right up until the October 21st dedication of Greenfield Village. Edward Cutler oversaw the final design elements needed to restore the building along with the actual work of reconstructing it. All the first- floor details, including the fireplace, mantle, and judges bench had to be re-created. The first-floor interior trim was reproduced in walnut, and was based on the original trim that survived on the second floor. The second floor, using a large amount of original material, including flooring, was also restored to its original appearance. Even the original plaster was collected, re-ground, and used to re-plaster the interior walls.

Views of the excavated original foundation, located 86 feet back from building’s second location. Lower view shows foundation for the original fireplace. September, 1929.

Views of the excavated original foundation, located 86 feet back from building’s second location. Lower view shows foundation for the original fireplace. September, 1929.

Based on the oldest of the original photographs, all new windows and exterior doors were also reproduced. Where possible, the original exterior walnut siding was also restored, and re-applied to the building and secured with brass screws.This was not a period technique, but rather a solution by Cutler to ensure the original siding with its worn nail holes, would stay in place.

The result was a place where Henry Ford could now display, and share his collection of Lincoln associated artifacts, including the most famous of all, the rocking chair from the presidential booth in Ford’s theater where Abraham Lincoln was sitting when he was shot by John Wilkes Booth in April of 1865.

Re-construction well under way in Greenfield Village on October, 2, 1929. The building would be complete for the October 21, dedication. The Sarah Jordan Boarding House can be seen in the distance.

Re-construction well under way in Greenfield Village on October, 2, 1929. The building would be complete for the October 21, dedication. The Sarah Jordan Boarding House can be seen in the distance.

The completed Logan County Courthouse in Greenfield Village as it appeared for the October 21 dedication.

The completed Logan County Courthouse in Greenfield Village as it appeared for the October 21 dedication.

The newly unpacked Ford’s Theater rocking chair in the Logan County Courthouse, January of 1930.

The interior of the completed Logan County Courthouse c.1935. It featured a display of Abraham Lincoln associated objects including Springfield furniture and the rocking chair from Ford’s Theater.

The interior of the completed Logan County Courthouse c.1935. It featured a display of Abraham Lincoln associated objects including Springfield furniture and the rocking chair from Ford’s Theater.

From 1929 until the mid-1980s, the building was left almost untouched as a shrine to Abraham Lincoln.

It was not until the mid-1980s that the research material was re-examined, primarily for preparations for much needed repairs to the now 50 plus year old restoration. In 1980, prior to the restoration work, the Lincoln assassination rocking chair was removed from the courthouse and placed in Henry Ford Museum. In 1984, the building underwent a significant restoration and was re-sided, the first- floor flooring was repaired, and extensive plaster repair and refinishing took place. In addition, a furnace was added (inside the judge’s bench), to provide adequate heat.

The interpretation of the building also was redefined and was re-focused away from the Abraham Lincoln shrine and more toward the stories of the history of our legal system and the civic lives of Americans in the 1840s. Gradually, many of the Lincoln artifacts were removed to appropriate climate controlled storage or display in Henry Ford Museum.

That brings us to the Greenfield Village opening of 2017. The Logan County Courthouse has now stood as long in Greenfield Village as it did in Postville, 88 years. It has had an interesting and storied history in both locations. Both the curatorial team, and the Greenfield Village programs team are excited to continue the process of ongoing research and improving the scholarship of the stories we tell there. We are working on some projects to accomplish just that for the near future and are looking forward to sharing all the details.

Continue ReadingHenry Ford, Michigan, Dearborn, Illinois, 20th century, 19th century, presidents, Logan County Courthouse, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, by Jim Johnson, Abraham Lincoln

Searching for Structural Integrity

One of the key aspects of the Dymaxion House in Henry Ford Museum is its central mast, which supports the entire structure. Buckminster Fuller, who created Dymaxion, had a lifelong interest in creating maximal structural strength with minimal materials and weight, most famously seen in his work with geodesic domes. When Fuller won his first commission for a geodesic structure, the Ford Rotunda, he worked with the Aerospace Engineering Lab at the University of Michigan to create a truss for load testing. Saved twice from being discarded by university staff, this test module was donated to The Henry Ford in 1993.

It’s newly digitized and available for viewing in our Digital Collections, along with many other artifacts related to geodesic domes, Buckminster Fuller, and the Dymaxion House.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

design, Michigan, Dearborn, Ford Motor Company, engineering, Buckminster Fuller, by Ellice Engdahl, digital collections

Behind the Scenes with IMLS: Cleaning Objects

One of the main components of The Henry Ford’s IMLS-funded grant is the treatment of electrical objects coming out of storage. This largely involves cleaning the objects to remove dust, dirt, and corrosion products. Even though this may sound mundane, we come across drastic visual changes as well as some really interesting types of corrosion and deterioration, both of which we find really exciting.

One of the main components of The Henry Ford’s IMLS-funded grant is the treatment of electrical objects coming out of storage. This largely involves cleaning the objects to remove dust, dirt, and corrosion products. Even though this may sound mundane, we come across drastic visual changes as well as some really interesting types of corrosion and deterioration, both of which we find really exciting. An electrical drafting board during treatment (2016.0.1.28)

An electrical drafting board during treatment (2016.0.1.28)

Conservation specialist Mallory Bower had a great object recently which demonstrates how much dust we are seeing settled on some of the objects. We’re lucky that most of the dust is not terribly greasy, and thus comes off of things like paper with relative ease. That said, it’s still eye-opening how much can accumulate, and it definitely shows how much better off these objects will be in enclosed storage.

Before and after treatment images of a recording & alarm gauge (2016.0.1.46)

The recording and alarm gauge pictured above underwent a great visual transformation after cleaning, which you can see in its before-and-after-treatment photos. As a bonus, we also have an image of the material that likely caused the fogging of the glass in the first place! There are several hard rubber components within this object, which give off sulfurous corrosion products over time. We can see evidence of these in the reaction between the copper alloys nearby the rubber as well as in the fogging of the glass. The picture below shows where a copper screw was corroding within a rubber block – but that cylinder sticking up (see arrow) is all corrosion product, the metal was actually flush with the rubber surface. I saved this little cylinder of corrosion, in case we have the chance to do some testing in the future to determine its precise chemical composition.

Hard rubber in contact with copper alloys, causing corrosion which also fogged the glass (also 2016.0.1.46). Hard rubber corrosion on part of an object – note the screw heads and the base of the post.

Hard rubber corrosion on part of an object – note the screw heads and the base of the post.

This is another example of an object with hard rubber corrosion. In the photo, you can see it ‘growing’ up from the metal of the screws and the post – look carefully for the screw heads on the inside edges of the circular indentation. We’re encountering quite a lot of this in our day to day work, and though it’s satisfying to remove, but definitely an interesting problem to think about as well.

There are absolutely more types of dirt and corrosion that we remove, these are just two of the most drastic in terms of appearance and the visual changes that happen to the object when it comes through conservation.

We will be back with further updates on the status of our project, so stay tuned.

Louise Stewart Beck is Senior Conservator at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, IMLS grant, conservation, collections care, by Louise Stewart Beck, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Strange sounds will soon float through the air at The Henry Ford. Ghostly, warbling, hypnotic sounds. Reverberations that might be described as pure science fiction—as seeming “out-of-this-world.” These provocative sounds will rise out of an instrument called the theremin, developed in 1920 by Russian and Soviet inventor Léon Theremin. Famously, it is one of the only instruments that is played without physically touching it, and is considered to be the world’s first practical, mass-produced, and portable electronic instrument. These instruments offer a deep range of sonic possibility; learning to play one is a stirring experience.

At Maker Faire Detroit, July 30-31, 2016, Dorit Chrysler will provide several theremin workshops with KidCoolThereminSchool, a workshop program “dedicated to inspire and nurture creative learning and expression through innovative music education, art and science.” On Saturday, youth workshops (ages 4-13) will be held on a first come-first served basis at 11am and 1pm, followed by an adult workshop (ages 14 and above) at 4pm. On Sunday, youth workshops will be held at 1pm, followed by an adult workshop at 4pm. Maker Faire attendees are encouraged to arrive early to guarantee a place in the workshop, as each session is limited to ten participants. Additional guests are welcome to observe the workshop and test a theremin afterwards. Workshops typically run 45mins to 1hour, and will be held in the upper mezzanine area in the Heroes of the Sky exhibit.

Dorit Chrysler is rarity in the realm of musical performance: she is one of the few theremin players in the world who is considered to be a virtuoso of the instrument. She has accompanied an impressive list of bands including The Strokes, and Blonde Redhead, Swans, Cluster, ADULT., Dinosaur Jr., and Mercury Rev. Additionally, as part of her visit to Maker Faire, Dorit will give a performance each day at 3:15pm in The Henry Ford’s Drive-In Theatre, followed by a short Q&A session.

Kristen Gallerneaux, our Curator of Communications and Information Technology, had the opportunity to speak with Dorit Chysler about theremins, her music career, and the importance of collaboration.

Can you explain, using a few key words or phrases—as fanciful as you want them to be—how the theremin sounds?

The granddaughter of the Lev Termen, the theremin's inventor once told me, you have to play the theremin with your soul - to me the sound at its best translates your slightest physical motions into a haunting & delicate soundscape, like weaving winds, tickled butterflies or howls to the moon, and yes, a theremin can sound exquisitely lyrical, but—at its worst, it can also sound like stepping on a cats tail.

How did your introduction to and love of the theremin as an instrument begin? What was your creative background before committing to the theremin?

Having studied musicology in Vienna, I had been an active composer and also played guitar and sang in a rock band - when encountering the theremin at a friend’s house, I was instantly touched by its unusual interface, dynamic potential, the quixotic efforts necessary in controlling its pitch -why had the theremin not been more popular? It clearly deserved more attention.

How can the presence of a theremin influence the structure of a song?

A theremin is surprisingly versatile - it can be applied in solo voicing (just like violin or guitar) or looping monophonic voices atop of each other, which creates a very unique weaving effect or dynamically in swoops and other gestural movements generated through its unique interface of motion translating into sound.

Are there any “quirks” to playing this instrument live?

Playing a theremin live can be a challenge, as circuitry, wind (outdoors) or Hearing Aid ‘Loop’ T-coil Technology in concert halls, just to name a few, can interfere with the instrument. In addition, if you don't hear yourself well onstage, it is impossible to play in tune—so if playing with other instruments, such as an orchestra or a band with drummers, it is a challenge that can only be mastered with your own mixer and an in ear mic. Needless to say, all of this does not contribute in making the theremin a more popular instrument, the technical challenge playing live is real but can be mastered.

While commercial theremins are available via Moog Music, Inc., the theremin you sometimes play in your live shows doesn’t look like a commercial model. Is there a story behind who built it? Any special skills that creator may have had to work hard to learn in order to make the instrument a reality?

I own several different theremin models and sometimes play a Hobbs Theremin, created by Charlie Hobbs. This prototypes has hand-wound coils and a very responsive volume antenna which permits very dynamic playing.

What is the strangest setting in which you have played the theremin?

Many diverse settings seem to offer themselves to a thereminist. Some of my favorite ones have been: playing in front of Nikola Tesla's ashes, resting inside a gold ball sitting on a red velvet pillow at the Tesla Museum in Belgrade, or inside an ancient stone castle ruin, atop a mountain in Sweden, or on a wobbly boat off Venice during sunset and with creaming ducks, at the Carnival in Brazil on a busy street filled with dancing people, and finally, a market place in a small town in Serbia, when an orthodox priest held his cross against the theremin to protect his people from "the work of the devil."

Could you talk a little about the importance of collaboration, and perhaps talk about a project that you are especially fond of where collaboration had a key role?

I strongly believe in collaboration—its challenges and the new and unforeseen places it may take you. My biggest challenge this year has been playing with the San Francisco Symphony orchestra, to be surrounded by a sea of acoustic instruments sounded incredible and was a great sonic inspiration. We all had to trust each other and some of the traditional classical musicians of the ensemble eyed the electric theremin with great suspicion! Also I enjoyed playing with Cluster, stone cold improvising together onstage, or with a loud rock ensemble, filling the main stage at Roskilde festival with Trentemoeller, looking at a sea of thousands of people. This Fall I am committed to projects in collaboration with a project in Detroit with the band ADULT., a French band called Infecticide (they remind me of a political French version of Devo), a children’s theremin orchestra, and a theremin musical production for Broadway. Stylistically a theremin can fit in nowhere or anywhere, which opens many doors of collaboration

Can you tell us a little bit about how KidCoolTheremin school began? What other sorts of venues have you travelled this program to?

KidCoolThereminSchool began very organically, when children and adults were so eager to try the theremin themselves after concerts. I developed a curriculum and started classes at Pioneerworks, a center for art and science in Red Hook, NY. We were supported by Moog Music in Asheville, NC, where I had been teaching students over the course of six months. KidCoolThereminSchool has been going global ever since, we have had sold out classes in Sweden, Switzerland, Detroit's MOCAD, Houston, NYC, Moogfest, Vienna, and Copenhagen. This fall, KidCoolThereminSchool will go to Paris and Berlin as well as free classes in Manhattan as part of the "Dame Electric" festival in NY, Sept. 13-18th.

Why is it important for young people and new adult audiences to have the chance to try a theremin?

Ever since its inception, the theremin as a musical instrument has been underestimated—it merely hasn’t found its true sound as of yet. In this age of technology, a theremin's unique interface of motion to sound, seems contemporary and accessible. Amidst a sea of information, the very physical and innovative approach to different playing techniques can allow each player to find their own voice of expression, learning to listen and experiment, to train motorics and musical skills in a playful and creative way.

What can people expect to learn at the KidCool workshops at Maker Faire?

Due to time restrictions, we will offer introductory classes on the theremin. We will go through the basics of sound generation—and ensemble playing is sometimes all it takes for someone to get inspired in wanting to dive further into the sonic world of the theremin.

Is there anything you are particularly excited to see at the museum?

Yes, the collection apparently holds two RCA theremins. They are currently not on display but we (the NY Theremin Society, which I cofounded) would very much like to help examine and determine what it would take to operate these instruments one day, and to even play them in concert at the museum in the future. For a long time now I wanted to see the permanent collection of The Henry Ford!

Europe, New York, immigrants, Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, women's history, technology, school, musical instruments, music, Maker Faire Detroit, events, education, childhood

Take Me Home Huey

The Vietnam War is remembered as “the Helicopter War” for good reason. The Huey helicopter played a pivotal role serving the U.S. Armed Forces in combat as well as bringing thousands of soldiers and civilians alike back to safety. The helicopter’s prominent rotor “chop” and striking visual as it flew in groups across the sky, became iconic symbols of a challenging period in our nation’s history; symbols that continue to evoke powerful feelings today.

The Henry Ford is proud to host a special display on the front lawn of Henry Ford Museum: Take Me Home Huey is mixed-media sculpture created from the remains of an historic U.S. Army Huey helicopter that was shot down in 1969 during a medical rescue in Vietnam.

Artist Steve Maloney conceived of the piece to draw attention to the sacrifices made by veterans of the U.S. Armed Forces, and the 50th anniversary of the start of the Vietnam War. Maloney partnered with Light Horse Legacy (LHL), a Peoria, Arizona-based nonprofit and USA Vietnam War Commemorative Partner focused on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. LHL acquired the Huey helicopter – #174 – from an Arizona boneyard, re-skinned and restored it, and delivered it to the Maloney to transform into art for healing.

Learn more about Take Me Home Huey here.

Greg Harris is Senior Manager of Events & Program Production at The Henry Ford.

Asia, Michigan, flying, events, Dearborn, by Greg Harris, art, 21st century, 20th century, 2010s, 1960s

Garage Art

Photo by Bill Bowen.

Model T mechanics are restoration artists in their own right.

The Henry Ford has a fleet of 14 Ford Model T’s, 12 of which ride thousands of visitors along the streets of Greenfield Village every year.

With each ride, a door slams, shoes skid across the floorboards, seats are bounced on, gears are shifted, tires meet road, pedals are pushed, handles are pulled and so on. Makes maintaining the cars and preserving the visitor experience a continuous challenge.

“These cars get very harsh use,” said Ken Kennedy, antique vehicle mechanic and T Shed specialist at The Henry Ford. “Between 150,000 and 180,000 people a year ride in them. Each car gives a ride every five to seven minutes, with the longest route just short of a mile. This happens for nine months a year.”

The T Shed is the 3,600-square-foot garage on the grounds of Greenfield Village where repairs, restoration and maintenance magic happen. Kennedy, who holds a degree in restoration from McPherson College in Kansas, leads the shed’s team of staff and volunteers — many car-restoration hobbyists just like him.

“I basically turned my hobby into a career,” quipped Kennedy, who began restoring cars long before college. His first project: a 1926 two-door Model T sedan. “I also have a 1916 Touring and a 1927 Willys-Knight. And I’m working on a Model TT truck,” he added.

April through December, the shed is humming, doing routine maintenance and repairs on the Model T’s as well as a few Model AA trucks that round out Greenfield Village’s working fleet. “What the public does to these cars would make any hobbyist pull their hair out. Doors opening and shutting with each ride. Kids sliding across the seats wearing on the upholstery,” said Kennedy. Vehicles often go through a set of tires every year. Most hobbyist-owned Model T’s have the same set for three-plus decades.

With the heavy toll taken on the vehicles, the T Shed’s staff often makes small, yet important, mechanical changes to the cars to ensure they can keep up. “We have some subtle things we can do to make them work better for our purpose,” said Kennedy. Gear ratios, for example, are adjusted since the cars run slow — the speed limit in Greenfield Village is 15 miles per hour, maximum. “The cars look right for the period, but these are the things we can do to make our lives easier.”

In the off-season, when Greenfield Village is closed, the T Shedders shift toward more heavy mechanical work, replacing upholstery tops and fenders, and tearing down and rebuilding engines. While Kennedy may downplay the restoration, even the conservation, underpinnings of the work happening in the shed, the mindset and philosophy are certainly ever present.

“Most of the time we’re not really restoring, but you still have to keep in mind authenticity and what should be,” he said. “It’s not just about what will work. You have to keep the correctness. We can do some things that aren’t seen, where you can adjust. But where it’s visible, we have to maintain what’s period correct. We want to keep the engines sounding right, looking right.”

Photo by Bill Bowen.

RESTORATION IN THE ROUND

Tom Fisher, Greenfield Village’s chief mechanical officer, has been restoring and maintaining The Henry Ford’s steam locomotives since 1988. “It was a temporary fill-in; I thought I’d try it,” Fisher said of joining The Henry Ford team 28 years ago while earning an engineering degree.

He now oversees a staff with similarly circuitous routes — some with degrees in history, some in engineering, some with no degree at all. Most can both engineer a steam-engine train and repair one on-site in Greenfield Village’s roundhouse.

“As a group, we’re very well rounded,” said Fisher. “One of the guys is a genius with gas engines — our switcher has a gas engine, so I was happy to get him. One guy is good with air brake systems. We feel them out, see where they’re good and then push them toward that.”

Fisher’s team’s most significant restoration effort: the Detroit & Lima Northern No. 7. Henry Ford’s personal favorite, this locomotive was formerly in Henry Ford Museum and took nearly 20 years to get back on the track.

“We had to put on our ‘way-back’ hats and say this is what we think they would have done,” said Fisher.

No. 7 is one of three steam locomotives running in Greenfield Village. As with the Model T’s, maintaining these machines is a balance between preserving historical integrity and modernizing out of necessity.

“A steam locomotive is constantly trying to destroy itself,” Fisher said. “It wears its parts all out in the open. The daily firing of the boiler induces stresses into the metal. There’s a constant renewal of parts.”

Parts that Fisher and his team painstakingly fabricate, cast and fit with their sturdy hands right at the roundhouse.

DID YOU KNOW?

The No. 7 locomotive began operation in Greenfield Village to help commemorate Henry Ford’s 150th birthday in 2013.

Additional Readings:

- Ingersoll-Rand Number 90 Diesel-Electric Locomotive, 1926

- Keeping the Roundhouse Running

- Model Train Layout: Demonstration

- Part Two: Number 7 is On Track

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, trains, The Henry Ford Magazine, railroads, Model Ts, Greenfield Village, Ford Motor Company, engineering, collections care, cars, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford