Posts Tagged disney

A Ride on the Magic Skyway at the New York World’s Fair

Loading Area for the Magic Skyway Ride at the Ford Pavilion, New York World's Fair, 1964-1965 / THF701306

On the first Friday of every month, our staff present interesting stories from our archives on The Henry Ford’s Instagram account as part of our “History Outside the Box” series. Earlier this year, Image Services Specialist Jim Orr took our followers on a virtual trip through time, back to the 1964–1965 New York World’s Fair. Particularly, Jim demonstrated what a ride on the Magic Skyway, an attraction designed by Walt Disney for Ford Motor Company’s Wonder Rotunda, would have looked and felt like. Take a quick trip to the Fair below!

New York, 1960s, 20th century, world's fairs, History Outside the Box, Ford Motor Company, Disney, cars, by Jim Orr, by Ellice Engdahl, archives

Disney Songs as Storytellers

Poster for Heroes and Villains: The Art of the Disney Costume.

Poster for Heroes and Villains: The Art of the Disney Costume.Inspired by the creative thought process of founder Walt Disney, everything that the Walt Disney Company does is based upon the power of story. This can range from the plot of a film to the backstory of a theme park attraction. In all cases, the sets, props, and costumes help to provide clues for the audience about story elements and characters.

The songs in a Disney film can also enhance the story, moving it forward through emotion, detail, and nuance. Through songs, the characters become more believable, helping the audience become more invested in the story. Here are some classic examples.

Babes in Toyland

Babes in Toyland was a popular 1961 Christmas musical featuring a cast of Mother Goose characters. It starred Annette Funicello as Mary Quite Contrary, Tommy Sands as Tom Piper, Ray Bolger as the evil and villainous Barnaby, and Ed Wynn as the Toymaker. Annette Funicello later recounted that this was her favorite filmmaking experience.

The film was based upon Victor Herbert’s popular 1903 operetta of the same name. Herbert, a composer, wrote it with Glen McDonough, an opera librettist, in an attempt to outdo the extremely popular stage musical The Wizard of Oz, then playing on Broadway. (This was, of course, decades before the 1939 movie The Wizard of Oz.) The Babes in Toyland operetta continued to be performed for many years on the stage, where it was embraced as a children’s classic.

Disney’s was the second film version of the Babes in Toyland operetta released at movie theatres (the first was a film by Laurel and Hardy) and it was the first in Technicolor. In the Disney version, the plot was changed quite a bit and many of the song lyrics were rewritten. Some of the song tempos were even sped up.

“March of the Toys” is the best-known portion of the score of Babes in Toyland. It was used in the sequence in which the Toymaker displays his toys for the human children who have strayed into Toyland. One can almost imagine the toys coming alive in this lively up-tempo march.

“Toyland,” a whimsical song about a magical land filled with toys for girls and boys, also debuted in the original version of Babes in Toyland. This song still shows up on Christmas playlists, as it has been covered by many vocalists over the years, including Nat King Cole, Perry Como, Jo Stafford, Johnny Mathis, and—most notably—Doris Day.

Into the Woods

“No One is Alone” comes from the 2014 Disney musical fantasy film Into the Woods, which was adapted from a 1986 musical theater production. This song was created by American composer, songwriter, and lyricist Stephen Sondheim. It appears at the end of Act II, as the four remaining leads (the Baker, Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, and Jack) try to understand the consequences of their wishes and decide to place community wishes above their own. The song serves to demonstrate that even when life throws its greatest challenges, you do not have to face them alone.

With its universal theme, this song has been used for many other purposes, including the Minnesota AIDS Project in 1994, and a speech by President Barack Obama during the tenth anniversary of 9/11.

Although this film is lesser known than many other Disney live-action films, Stephen Sondheim is one of the most important figures in 20th-century musical theater, known for tackling dark, complex, unexpected themes that range far beyond the genre’s traditional subjects. He wrote the music for West Side Story, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

Beauty and the Beast

Costumes from the live-action movie Beauty and the Beast in the Heroes and Villains: The Art of the Disney Costume exhibit. / THF191450

The song “Beauty and the Beast” was written by lyricist Howard Ashman and composer Alan Menken for the Disney animated feature film of the same name (1991). This, truly the film’s theme song, was recorded by American-British-Irish actress Angela Lansbury in her role as the voice of the character Mrs. Potts. Lansbury was hesitant to record “Beauty and the Beast” because she felt that it was not suitable for her aging singing voice, but ultimately she completed the song in one take. It was also recorded as a pop song for the closing credits by the duet of Canadian singer Celine Dion and American singer Peabo Bryson. It was released as the only single from the film’s soundtrack. Both versions of “Beauty and the Beast” were very successful, garnering both Golden Globe and Academy Awards for Best Original Song.

Considered to be among Disney’s best and most popular songs, “Beauty and the Beast” has since been covered by numerous artists. In the 2017 live-action adaptation of the animated film, it was sung by Emma Thompson as Mrs. Potts and as a duet by Ariana Grande and John Legend during the end credits. In addition to Beauty and the Beast, Howard Ashman and Alan Menken collaborated on the music and lyrics for two other beloved Disney animated films—The Little Mermaid and Aladdin—before Ashman’s untimely death in 1991.

Mary Poppins

Costume from Mary Poppins in the Heroes and Villains: The Art of the Disney Costume exhibit. / Photo by Real Integrated for The Henry Ford

Mary Poppins was an incredibly popular 1964 Disney live-action film. All the songs for this film were written by the inimitable Sherman brothers. Robert and Richard Sherman were hired by Walt Disney himself to be his staff songwriters in 1961. While at Disney, they wrote more motion-picture musical scores than any other songwriters in the history of film, including Mary Poppins, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, all but one song from The Jungle Book, Bedknobs and Broomsticks, and The Aristocats. But they are possibly best known for their can’t-get-them-out-of-your-head songs from two Disney theme park attractions: “There’s a Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow” from the Carousel of Progress and “It’s a Small World (After All)” from the attraction of the same name.

But, back to Mary Poppins. First, the song “Feed the Birds” speaks of an old beggar woman who sits on the steps of St. Paul’s Cathedral, selling bags of breadcrumbs to passers-by for tuppence a bag so they can feed the pigeons. The scene is reminiscent of the real-life seed vendors of Trafalgar Square in London. It is intended to be a lesson about charity and the merits of giving to others.

The song was regarded as one of Walt Disney’s favorite songs. Robert Sherman recalled:

“On Fridays, after work, Walt Disney would often invite us into his office and we’d talk about things that were going on at the Studio. After a while, he’d wander to the north window, look out into the distance and just say, ‘Play it.’ And Dick would wander over to the piano and play ‘Feed the Birds’ for him. One time just as Dick was almost finished, under his breath, I heard Walt say, ‘Yep. That’s what it’s all about.’ ”

“A Spoonful of Sugar Helps the Medicine Go Down” is an up-tempo number sung by Julie Andrews as Mary Poppins as she instructs the children, Jane and Michael, to clean their room. Although the task is daunting, she tells them that, with a good attitude, it can be fun. Story has it that Robert Sherman, the primary lyricist of the duo, worked an entire day trying to come up with a song idea for this scene. As he walked in the door at home that evening, his wife, Joyce, informed him that the children had gotten their polio vaccine that day. He asked his son Jeffrey if it hurt, thinking he had received a shot. Jeffrey responded that the medicine was put on a cube of sugar and that he swallowed it. By the next morning, Robert had the title of his song. Richard put a melody to the lyric and the song was born.

Finally, “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious” is sung by Julie Andrews as Mary Poppins and Dick Van Dyke as Bert the chimney sweep in the live-action film’s unique animated sequence—just after Mary Poppins wins a horse race. Flush with her victory, she is immediately surrounded by reporters who pepper her with leading questions and comment that she is probably at a loss for words. Mary disagrees, suggesting that at least one word is appropriate for the situation—a word to say when you have nothing to say, and that is: Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious!

The Sherman Brothers have given several conflicting explanations for this word’s origin, in one instance claiming to have coined it themselves. But, this was disproven when two other songwriters sued the Walt Disney Company, claiming to have written a song using that word in 1949. The Disney publishers ultimately won the lawsuit because they produced affidavits showing that many variants of the word had been known prior to 1949.

These are just a few of the many memorable songs that enhance the stories in Disney animated and live-action films. Which songs from Disney films are your favorites?

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

Walt Disney Visits The Henry Ford

Walt Disney spent years imagining his ground-breaking entertainment venue, Disneyland, before it opened in 1955. Disney found inspiration for this remarkable theme park from many people and places.

Walt Disney (1901–1966) spent his most memorable childhood years in Marceline, Missouri, leaving him with a great fondness for small town America. Disney's early passion for cartoon drawing and humor blossomed in 1928 with his first major success, the Mickey Mouse animated cartoon character. By the 1930s, Disney headed a thriving motion picture studio making animated cartoons and live action movies. He explained his interest in developing a theme park to his biographer, Bob Thomas:

“It all started when my daughters were very young, and I took them to amusement parks on Sunday. I sat on a bench eating peanuts and looking around me. I said to myself, why can't there be a better place to take your children, where you can have fun together? Well, it took me about fifteen years to develop the idea.”

While on business trips and family vacations, Disney visited not only amusement parks, but also fairs, expositions, tourist attractions, and zoos to further his vision of creating an extraordinary family leisure experience. One of these places was Greenfield Village, which Walt Disney visited several times during the 1940s.

Walt Disney Posing in the Greenfield Village Tintype Studio, 1940 / THF109756

Walt Disney paid his first visit to Greenfield Village on April 12, 1940. William B. Stout, an industrial designer best known for the Ford Tri-Motor airplane and the aerodynamic Scarab car, served as Disney's escort as he toured Henry Ford's historical village and museum. The Greenfield Village Journal, a daily administrative report, described Disney’s visit that day:

“Walt Disney, creator of the world-famous movie character, Mickey Mouse, visited the Village and Museum today. He showed great interest in everything mechanical, examining engines and old autos closely. He had a good time with Mr. Tremear while posing for a tin-type. In the Museum Theater he spoke for a few moments to the school children. He was accompanied by Mrs. Disney, and by Ben Sharpsteen, his chief animator. Wm B. Stout was his host.”

Walt Disney Shows Harriet Bennett How to Draw Mickey Mouse during a Visit to Henry Ford Museum, April 12, 1940 / THF118884

During Disney's tour, he stopped at the Tintype Studio to pose for photographer Charles Tremear, autographing one of his tintypes for display there. Disney also spent a few minutes talking with students from the Greenfield Village Schools, who had gathered in the museum's theater to greet him. (Henry Ford established a school system in his museum and village complex several years before his historical enterprise was formally opened to the public in 1933.) Ford Motor Company photographer George Ebling—who was often asked to take personal photographs for Henry Ford—captured images of Disney's delightful visit with the students.

Walt Disney and Family Visiting Henry Ford Museum, August 1943 / THF130871, THF130883, THF119434

On August 20, 1943, Disney again visited Henry Ford Museum. He; his wife, Lillian; and their daughter, Diane, posed for photographs with examples of some of the historical modes of transportation displayed there. Disney’s joyful, childlike expression embodies the experience he hoped to create for families visiting what would come to be Disneyland.

Walt Disney came back to Greenfield Village five years later, on August 23, 1948. Disney and one of his animators, Ward Kimball—who shared Disney's longtime fascination with railroads—had traveled to Chicago to attend the Railroad Fair. They decided to take a side trip to Greenfield Village. During the visit to Greenfield Village, Disney once again made a stop at the Tintype Studio, where he and Kimball were photographed by tintypist Charles Tremear.

Walt Disney and Ward Kimball Posing in the Greenfield Village Tintype Studio, 1948 / THF109757

By the late 1940s, Disney's ideas for a themed entertainment park had progressed substantially. On the train ride back to California, he shared his ideas with Kimball, then summarized them in a memo dated August 31, 1948. An excerpt of this memo seems to echo aspects of Greenfield Village: “The Main Village, which includes the Railroad Station, is built around a village green or informal park … Around the park will be built the town. At one end will be the Railroad Station; at the other end, the Town Hall…”

When Disneyland opened in Anaheim, California, in 1955, it quickly captured the public’s imagination. In his innovative theme park, Walt Disney drew inspiration from his many interests and experiences to create an entirely new kind of family entertainment. To learn more, check out this blog post!

This post by Cynthia Read Miller, former Curator of Photography and Prints at The Henry Ford, originally ran in September 2005 as part of our Pic of the Month series. It was reformatted for the blog by Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford.

photographs, popular culture, by Saige Jedele, by Cynthia Read Miller, Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, Disney

How Did World’s Fairs Encourage Playfulness?

Illustration by Mia Saine

I recently visited the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair site, now part of Flushing Meadows Corona Park in Queens. I gawked at the still-standing central icon, the Unisphere, then searched for long-forgotten ruins scattered about.

Perhaps most striking were the still-existing pathways with their original concrete benches and drinking fountains. I could picture the people—the fairgoers—who had traveled from near and far to visit this temporary but extraordinary place, a place of wonder and delight, a place of enjoyment, leisure, and playfulness—a world’s fair.

The 1964-65 World’s Fair was a failure in many respects. It never reached its projected attendance and almost went bankrupt. When most large nations declined to participate, smaller nations and American states filled the gap. The fair is probably best remembered as a showcase for American corporations, with an endless array of new products displayed inside midcentury modern structures.

Nowhere was the blend of design and playfulness more apparent than in the corporate attractions designed by Walt Disney and his Imagineers, especially Ford Motor Company’s Magic Skyway. Here guests embarked on “an exciting ride in a company-built convertible through a fantasy of the past and future in 12 minutes.” When Ford added new Mustang convertibles to the ride mere months before the fair’s opening, this only added to the anticipation and enjoyment.

The Unisphere, a 12-story-high model of Earth which embodied the 1964-65 New York World's Fair theme of "Peace Through Understanding," celebrating "Man's Achievement on the Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe," can be seen through the window in this photo of a car on the Magic Skyway. / THF114472

Walt Disney remarked about the attraction: “It could never happen in real life, but we can achieve the illusion by creating an adventure so realistic that visitors will feel they have lived through a wonderful, once-in-a-lifetime experience.”

This could well sum up the overall appeal of world’s fairs.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. This post was adapted from an article first published in the June–December 2021 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

popular culture, Ford Motor Company, Disney, world's fairs, The Henry Ford Magazine, by Donna R. Braden

Walt Disney and His Creation of Disneyland

Postcard, “Disneyland,” 1975. THF 207872

Welcome to Disneyland!

Disneyland was created from a combination of Walt Disney’s innovative vision, the creative efforts and technical genius of the team he put together, and the deep emotional connection the park elicits with guests when they visit there. Walt Disney himself claimed, “There is nothing like it in the entire world. I know because I’ve looked. That’s why it can be great: because it will be unique.” Here’s the story of how Walt created Disneyland, the first true theme park.

Souvenir Book, “Disneyland,” 1955. THF 205151

Disneyland is much like Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World in Florida, but it’s smaller and more intimate. To me, it seems more “authentic.” It’s like you can almost feel the presence of Walt Disney everywhere because he had a personal hand in things.

Walt Disney posing the Greenfield Village Tintype Studio, 1940. THF 109756

In creating Disneyland, Walt Disney challenged many rules of traditional amusement parks. We’ll see how. But first…since he insisted that everyone he met call him by his first name, that’s what we’ll do. From now on, I’ll be referring to him as Walt!

Souvenir Book, “Disneyland,” 1955. THF 205155

DISNEY INSIDER TRIVIA: Do you know where Walt Disney’s inspiration for Main Street, USA, came from?

ANSWER: Born in 1901, Walt loved the bustling Main Street of his boyhood home in Marceline, Missouri. Marceline later provided the inspiration for Disneyland’s Main Street, USA.

Map and guide, “Hollywood Movie Capital of the World,” circa 1942. THF 209523

After trying different animated film techniques in Kansas City, Walt left to seek his fortune in Hollywood.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Valentine, 1938. THF 335750

There, he made a name for himself with Mickey Mouse (1927) and—10 years later—the first full-length animated feature film, Snow White. Walt innately understood what appealed to the American public and later brought this to Disneyland.

Handkerchief, circa 1935. THF 128151

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: Here’s how Mickey Mouse looked on a child’s handkerchief in the 1930s.

“Merry-Go-Round-Waltz,” 1949. THF 255058

Walt claimed the idea of Disneyland came to him while watching his two daughters ride the carousel in L.A.’s Griffith Park. There, he began to imagine a clean, safe, friendly place where parents and children could have fun together!

Herschell-Spillman Carousel. THF 5584

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: That carousel in Griffith Park was built in 1926 by the Spillman Engineering Company—a later name for the Herschell-Spillman Company, the company that made the carousel now in our own Greenfield Village in 1913! Here’s what ours looks like.

Coney Island, New York, circa 1905 – THF 241449

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: For more on the evolution of American amusement parks, see my blog post, “From Dreamland to Disneyland: American Amusement Parks.”

1958 Edsel Bermuda Station Wagon Advertisement, “Dramatic Edsel Styling is Here to Stay.” THF 124600

The decline of these older amusement parks ironically coincided with the rapid growth of suburbs, freeways, car ownership, and an unprecedented baby boom—a market primed for pleasure travel and family fun!

Young Girl Seated on a Carousel Horse, circa 1955. THF 105688

Some amusement parks added “kiddie” rides and, in some places, whole new “kiddie parks” appeared. But that’s not what Walt had in mind. Adults still sat back and watched their kids have all the fun.

Chicago Railroad Fair Official Guidebook, 1948. THF 285987

Walt’s vision for his family park also came from his lifelong love of steam railroads. In 1948, he and animator/fellow train buff Ward Kimball visited the Chicago Railroad Fair and had a ball. Check out the homage to old steam trains in this program.

Tintype of Walt and Ward. THF 109757

After the Railroad Fair, Walt and Ward visited our own Greenfield Village, where they enjoyed the small-town atmosphere during a special tour. At the Tintype Studio, they had their portrait taken while dressed up as old-time railroad engineers.

Walt Disney and Artist Herb Ryman with illustration proposals for the Ford Pavilion, 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. THF 114467

DISNEY INSIDER TRIVIA: Walt Disney used the word Imagineers to describe the people who helped him give shape to what would become Disneyland. What two words did he combine to create this new word?

ANSWER: Walt hand-picked a group of studio staff and other artists to help him create his new family park. He later referred to them as Imagineers—combining the words imagination and engineering. This image shows Walt with Herb Ryman—one of his favorite artists.

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: For a deeper dive on an early female Imagineer, see my blog post, “The Exuberant Artistry of Mary Blair.”

Postcard viewbook of Los Angeles, California. THF 7376

Walt continually looked for new ideas and inspiration for his park, including places around Los Angeles, like Knott’s Berry Farm, the Spanish colonial-style shops on Olvera Street, and the bustling Farmer’s Market—one of Walt’s favorite hangouts.

Times Square – Looking North – New York City, August 7, 1948. THF 8840

Walt also worried about how people got fatigued in large and crowded environments. So, he studied pathways, traffic flow, and entrances and exits at places like fairs, circuses, carnivals, national parks, museums, and even the streets of New York City.

Souvenir Book, “Disneyland,” 1955. THF 205154

Studying these led to Walt’s first break from traditional amusement parks: the single entrance. Amusement park operators argued this would create congestion, but Walt wanted visitors to experience a cohesive “story”—like walking through scenes of a movie.

Souvenir Book, “Disneyland,” 1955. THF 205152

Another new idea in Walt’s design was the central “hub,” that led to the park’s four realms, or lands, like spokes of a wheel. Walt felt that this oriented people and saved steps. Check out the circular hub in front of the castle on this map.

Disneyland cup & saucer set, 1955-1960. THF 150182

A third rule-challenging idea in Walt’s plan was the attractor, or “weenie” for each land—in other words, an eye-catching central feature that drew people toward a goal. The main attractor was, of course, Sleeping Beauty Castle.

To establish cohesive stories for each land, Walt insisted that the elements in them fit harmoniously together—from buildings to signs to trash cans. This idea—later called “theming”—was Walt’s greatest and most unique contribution.

Halsam Products, “Walt Disney’s Frontierland Logs,” 1955-1962. THF 173562

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: This Lincoln Logs set reinforced the look and theming of Frontierland in Disneyland.

Woman’s Home Companion, March 1951. THF 5540

DISNEY INSIDER TRIVIA: Which came first, Disneyland the park, or Disneyland the TV show?

ANSWER: To build his park, Walt lacked one important thing—money! So, he took a risk on the new medium of TV. While most Hollywood moviemakers saw TV as a fad or as the competition, Walt saw it as “my way of going direct to the public.” Disneyland the TV show premiered October 27, 1954—with weekly features relating to one of the four lands and glimpses of Disneyland the park being built.

Child’s coonskin cap, 1958-1960. THF 8168

The TV show was a hit, but never more than when three Davy Crockett episodes aired in late 1954 and early 1955.

Souvenir Book, “Disneyland,” 1955. THF 205153

Disneyland, the park, opened July 17, 1955, to special guests and the media. So many things went wrong that day that it came to be called “Black Sunday.” But Walt was determined to fix the glitches and soon turned things around.

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: For more on “Black Sunday” and the creation of Disneyland, see my blog post, “Happy Anniversary, Disneyland.”

Walt Disney World Magic Kingdom guidebook, 1988. THF 134722

Today, themed environments from theme parks to restaurants to retail stores owe a debt to Walt Disney. Sadly, Walt Disney passed away in 1966. It was his brother Roy who made Walt Disney World in Florida a reality, beginning with Magic Kingdom in 1971.

Torch Lake steam locomotive pulling passenger cars in Greenfield Village, August 1972. THF 112228

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: In an ironic twist, a steam railroad was added to the perimeter of Greenfield Village for the first time during a late 1960s expansion—an attempt to be more like Disneyland!

Marty Sklar speaking at symposium for “Behind the Magic” at Henry Ford Museum, November 11, 1995. THF 12415

In 2005, The Henry Ford celebrated Disneyland’s 50th anniversary with a special exhibit, “Behind the Magic: 50 Years of Disneyland.” The amazing and talented Marty Sklar, then head of Walt Disney Imagineering, made that possible.

DISNEY INSIDER INFO: Check out this blog post I wrote to honor Marty’s memory when he passed away in 2017.

During these unprecedented times, Disneyland has begun its phased reopening. When you feel safe and comfortable going there, I suggest adding it to your must-visit (or must-return) list. When you're there, you can look around for Walt Disney's influences, just like I do.

Donna Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

Continue ReadingCalifornia, 20th century, popular culture, Disney, by Donna R. Braden, #THFCuratorChat

Lady and the Tramp Celebrates 65 Years

June 1955 magazine advertisement for the release of Lady and the Tramp. THF145583

Although this animated feature film received mixed reviews when it was first released on June 22, 1955, Walt Disney’s Lady and the Tramp has since become a classic. It is beloved for its songs, its story, its gorgeously rendered and meticulously detailed settings, and its universal themes of love and acceptance—not to mention that scene with the spaghetti! Numerous story artists and animators contributed their talents to creating this film, but it would take years before Walt Disney would finally give it his nod of approval.

Unlike other Disney animated films of the time, Lady and the Tramp is not based upon a venerable old fairy tale or a previously published book. Its origins can be traced back to 1937, when Disney story artist Joe Grant showed Walt Disney some sketches and told him of his idea for a story based upon the antics of his own English Springer Spaniel named Lady, who was “shoved aside” when the family’s new baby arrived. Walt encouraged Grant to develop the story but was unhappy with the outcome—feeling that Lady seemed too sweet and that the story didn’t have enough action. For the next several years, Grant and other artists worked on a variety of conceptual sketches and many different approaches.

In 1945, the storyline took a drastic turn, which ultimately led to its final film version. That year, Walt Disney read a magazine short story called, “Happy Dan, the Cynical Dog.” Here, in the story of a cynical, devil-may-care dog, Walt found the perfect foil for the prim and proper Lady. By 1953, the film had evolved to the point that Walt asked Ward Greene, the short story’s author, to write a novelization of it. It is Greene—not Joe Grant—who received credit in the final film. Walt couldn’t resist adding a personal tidbit to the story. According to his telling of the story, the opening scene came from his own experience of giving his wife a puppy as a gift in a hat box to make up for having forgotten a dinner date with her.

Interestingly, the spaghetti-eating scene was almost cut, as Walt Disney initially thought it was silly and unromantic. But animator Frank Thomas had such a strong vision for the scene that he completed all the animation for it before showing it to Walt, who was so impressed he agreed to keep in the now-iconic scene.

1955 charm bracelet of the dogs in Lady and the Tramp, likely a souvenir obtained at Disneyland. THF8604

Since the dogs were the main characters of the film, it seemed only natural to both show and tell the story from the dogs’ point of view. The animators studied many real dogs to capture their movements, behaviors, and personalities, while the scenes themselves were shot from a low “dog’s-eye-view” perspective.

A depiction of Main Street, U.S.A. at Disneyland from the 1955 Picture Souvenir Book to the park. THF205154

The film’s setting—early 20th century small-town America—referenced Walt Disney’s own return to his roots, particularly his growing up in the small town of Marceline, Missouri. As the setting was coming to life on film, a real live 3D version of it was being constructed at Disneyland, Walt Disney’s new park in Anaheim, California. Disneyland opened a mere three weeks after the film was released.

Although the setting hearkened back to the past, the filmmaking technique that Walt chose was typically state-of-the-art. As Walt marked the growing interest in widescreen film technology, he decided this would be the first of his animated films to use CinemaScope. To fill in the extra-wide space of this format, the animators extended the backgrounds—resulting in settings that are unusually breathtaking, detailed, mood-setting and, when the story called for it, filled with dramatic tension. Unfortunately, many theatres were not equipped with CinemaScope, so Walt decided that two versions of the film had to be created, forcing layout artists to scramble to restructure key scenes for a standard format as well. CinemaScope ultimately proved too expensive and did not last past the early 1960s. But its influence on Lady and the Tramp lives on—a testament to Walt’s commitment to filmmaking innovation.

Although souvenirs related to Lady and the Tramp are hard to come by these days, I was thrilled to find these salt-and-pepper shakers and collectible pins over several visits to Walt Disney World.

I saw Lady and the Tramp when it was re-released in theatres in 1962. I was nine years old at the time and I was completely enraptured. The details and setting—from the frilly ladies’ dresses, dapper men’s suits, and overstuffed furniture inside Lady’s house to the horses’ clip-clopping down the cobblestone streets—seemed like old photographs come to life. Taking in these details on the big screen as a girl, I was transfixed. Is this where my interest in history began?

After seeing Lady and the Tramp at the movies, I also became obsessed with wanting a dog. Not just any dog. I wanted Lady, or a cocker spaniel as close to Lady as I could get. I dreamed of her, drew pictures of her, transferred her personality onto the stuffed dogs I inevitably got as presents. When I was in eighth grade, my parents finally relented. One day my Mom surprised us and took us kids down to the animal shelter to get a dog. It wasn’t a cocker spaniel. But we did find a little golden-haired puppy that was a fine substitute.

I don’t know that I thought much of Tramp when I was a girl. He was wayward, a nuisance, too different. But from my older perspective, I see that Lady meeting, and ultimately falling for, Tramp was really a symbol of what happens in your life. Forced out of your comfort zone, broadening your horizons, seeing things from new perspectives, taking life’s curves with grace until, rather than resisting it, you accept it—even embrace it.

Who knew, when I was a girl, that this movie was not just about dogs but about life?

Note: The complete story of the making of Lady and the Tramp, including Joe Grant’s contributions, can be found in the bonus feature, “Lady’s Pedigree: The Making of Lady and the Tramp,” in the 50th Anniversary DVD of Lady and the Tramp.

Donna R. Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

The Exuberant Artistry of Mary Blair

Mary Blair was the artist for this hand-pulled silkscreen print, used in a guest room at Disney’s Contemporary Resort, Walt Disney World, 1973 to early 1990s. THF181161

When Disney’s Contemporary Resort opened at Walt Disney World in 1971—coinciding with the opening of Magic Kingdom—guests almost immediately complained about their rooms. The rooms seemed cold and hard. They lacked personality. Guests couldn’t even figure out how to operate the new-fangled recessed lighting. So, within two years, the rooms were refurbished with new textiles, fabrics, traditional lamps, and high-quality prints of Mary Blair’s original design. These prints were adapted from the individual scenes of a massive tile mural that she had created for the Contemporary Resort’s central atrium. The hand-pulled silk-screened prints, framed and hung on the walls over the beds, brought much-needed warmth, color, and a sense of playful exuberance to the rooms. More importantly—but probably unbeknownst to most guests—they reinforced Mary Blair’s deep, longstanding connection to Disney parks, attractions, and films that ultimately dated back to a personal friendship with Walt Disney himself.

Mary Blair was born Mary Browne Robinson in 1911 in rural Oklahoma. She developed a love of art early in her childhood and went on to major in fine arts at San Jose State College. She won a prestigious scholarship to the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles (which later became the California Institute of the Arts) and studied under the tutelage of Chouinard’s director of illustration, Pruett Carter. Carter was one of the era’s most accomplished magazine illustrators and stressed the importance of human drama, empathy, and theatre in illustration. Mary later recalled that he was her greatest influence.

By the late 1930s, Mary and her husband, fellow artist Lee Blair, were unable to survive off the sales of their fine art and began to work in Los Angeles’s animation industry. In 1941, both were working at Disney and had the opportunity to travel with Walt Disney and a group of Disney Studio artists to South America to paint as part of a government-sponsored goodwill trip. While on this trip, Mary grew into her own as an artist and found the bold and colorful style for which she would be known.

Mary Blair became one of Walt Disney’s favored artists, appreciated for her vibrant and imaginative style. She recalled, “Walt said that I knew about colors he had never heard of.” In her career at Disney, she created concept art and color styling for many films, including Dumbo (1941), Saludos Amigos (1942), Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951), and Peter Pan (1953). She left Disney after her work on Peter Pan to pursue freelance commercial illustration, but returned when Walt Disney specifically requested her help to create the “it’s a small world” attraction for the 1964-5 New York World’s Fair (later brought back to Disneyland and also recreated in Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World).

Before Walt Disney passed away in 1966, he commissioned Mary to produce multiple large-scale murals, including the one for the interior of the Contemporary Resort at Walt Disney World in Florida. The mural, completed in 1971, was her last work with Disney. Entitled “The Pueblo Village,” it featured 18,000 hand-painted, fire-glazed, one-foot-square ceramic tiles celebrating Southwest American Indian culture, prehistoric rock pictographs, and the Grand Canyon. (Because Mary’s depictions of Native Americans admittedly lack attention to the serious study of indigenous people in that region, they might be criticized as racial stereotyping).

When the guest rooms at the Contemporary Resort were renovated again in the early 1990s, the high-quality prints were removed. But the massive tile mural stoically remains at the center of the Resort’s ten-story atrium—a reminder of Mary Blair’s exuberant artistry and her many contributions to Disney parks and films.

For more on Mary Blair’s contributions, along with the previously unrecognized contributions of numerous other female artists who worked on Disney films, see the book The Queens of Animation: The Untold Story of the Women Who Transformed the World of Disney and Made Cinematic History, by Nathalia Holt (2019).

This blog post was a collaborative effort by Donna Braden, Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford, and Katherine White, Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

Indigenous peoples, Florida, 20th century, 1970s, 1960s, women's history, Disney, design, by Katherine White, by Donna R. Braden, art

The Real Toys of “Toy Story 4”

Chatty Cathy Talking Doll, ca. 1963, an inspiration for Gabby Gabby. THF 173150

Since 1995, Disney-Pixar’s “Toy Story” films have led the industry in combining computer-generated animation with powerful, heartfelt stories. One of the reasons that adults and kids alike are drawn to these films is the clever selection of toys. More often than not, these are based upon real toys that are fondly remembered by viewers from different generations (see several examples of these from The Henry Ford’s collections in the blog post, “The Real Toys of Toy Story”).

This summer’s release of “Toy Story 4”—with its cast of old friends along with several newly introduced toys—allows us the perfect opportunity to once again delve into The Henry Ford’s collections and see what real toys provided inspiration for this fourth “Toy Story” installment.

The Heroes

Kentucky Fried Chicken Spork, 1978-90. THF173933

A heroic spork? Yes, indeed! This time around, Pixar decided to explore what would happen when a handmade toy named Forky (with a plastic spork for a body) meets the old gang of mass-manufactured toys.

Sporks have a long, mostly unsuccessful history. Think about it. When you combine a spoon and a fork together, neither of them is going to work very well. Interlocking or folding sets of camp utensils have always been more popular with backpackers and Boy Scouts. Nevertheless, by the 1970s, plastic sporks were making their way into fast-food restaurants—to use for, as Forky describes it, "soup, salad, maybe chili, and then the trash!” Kentucky Fried Chicken was one of the first fast-food chains to regularly feature sporks, like the one shown here.

Image of Little Bo-Peep as part of Mother Goose Series, trade card for baking soda, John Dwight & Co., 1900. THF294575

In “Toy Story 4,” Bo Peep returns as a much more assertive and heroic character. Here we learn that she was once part of a lamp that Andy’s sister, Molly, had in her bedroom to help her fall asleep. In fact, the classic nursery rhyme, Little Bo-Peep—first printed in full in 1810—reveals that this young shepherdess lost her sheep because she had also fallen asleep!

Other connections exist between the old nursery rhyme and the newer, more independent Bo Peep. In the nursery rhyme, Bo Peep’s sheep lose their way because sheep are known to flock together. In “Toy Story 4,” Bo Peep’s three sheep are also inseparable—in fact, they are molded together as one piece, leading to often humorous results! In addition, a shepherdess would have traditionally used her crook not only to manage her sheep but also to defend them from attack by predators. In the film, Bo Peep similarly uses her crook to keep our heroes from harm.

Polly Pocket Watch Happy Meal Toy, 1995. THF141193

The appearance of Giggles McDimple in “Toy Story 4” likely delighted girls who grew up in the 1990s, as Giggles and her “home” reference the highly popular Polly Pockets of that era. These were first conceived by a British Dad for his daughter in 1983, using a powder compact as a tiny house that could fit in a pocket. Bluebird Toys, of Swindon, England, licensed the concept when these first appeared on the market in 1989, with Mattel in charge of distribution. In 1998, Mattel purchased the rights to manufacture Polly Pockets, then immediately redesigned them into larger dolls with changing garments. While various versions were produced after that, the original minuscule figures with jointed legs and peg-like bases that slotted into holes inside their cases never returned.

In “Toy Story 4,” Giggles compensates for her minuscule size by displaying an air of confidence and a can-do attitude—just the kind of out sized personality that little girls of the 1990s might have ascribed to their own Polly Pockets.

Evel Knievel X-2 Sky Cycle Toy, 1976-8. THF 302676

Duke Caboom—"Canada’s Greatest Stuntman”—is not an exact imitation of Evel Knievel, but this “Toy Story 4” character was certainly inspired by the famed 1970s stunt daredevil. Robert Craig Knievel, who was known at an early age for his combined athletic prowess and guts, became a national sensation in the 1970s, when he was featured several times on “ABC’s Wide World of Sports.” Knievel’s tremendous crowd appeal motivated Ideal to reproduce an action-figure version of him along with various stunt-related accessories—like this X-2 Sky Cycle that replicates the one he used during an attempted jump over Snake River Canyon, Idaho, in 1974.

During the peak of his popularity, Knievel’s flashy white leather jumpsuit and reputation for keeping his word helped reinforce his heroic, larger-than-life image. That is, until 1978, when he was convicted of assaulting the author of a book written about him and his popularity quickly plummeted. The tragic backstory of Duke Caboom and his kid who rejected him is a fitting connection to the real-life 1970s Evel Knievel and his young fans.

G.I. Joe Desert Troop Dusty with Sandstorm, his coyote, 1990-91. THF 94338

Combat Carl makes a small but unforgettable appearance in “Toy Story 4”—especially if you stay to the very end of the credits. He played a bit part in the first “Toy Story” film, then a larger role in Pixar’s 2013 Halloween TV special, “Toy Story of Terror!” Combat Carl is an everyman military action figure reminiscent of G.I. Joe action figures of the 1980s and ‘90s. Mattel introduced the first G.I. Joe in 1964—a 12” poseable version that directly referenced the military men who saw action during World War II and the Korean War. An African-American version of G.I. Joe was introduced in 1965.

As a result of the unpopular Vietnam War in the late 1960s and the rising price of plastic in the 1970s, G.I. Joes declined in popularity until they were discontinued in 1978. But they made a stunning comeback during the 1980s as 3-3/4” adventure-team action figures. This G.I. Joe action figure from The Henry Ford’s collection, named Dusty, was introduced in 1991, after the Persian Gulf War inspired toys based upon the real-life conflict. Exuding a great deal of self-possessed machismo but also tugging at our heartstrings a bit, Combat Carl always leaves us rooting for him.

The Villains

Shown on the right side of the page, Chatty Cathy is featured in the 1964 Sears Roebuck & Co. Christmas Catalog. Note her Gabby Gabby-like freckles! THF287020

At first glance, the scheming Gabby Gabby appears to have been based upon Chatty Cathy, introduced to the American public in 1960 as the first in a new line of Mattel talking dolls. Like Gabby Gabby in the film, Chatty Cathy’s “voice” was activated by a pull string in the back. The first Chatty Cathy, who had blue eyes and sported a blonde bobbed hairdo, recited 11 phrases at random via a record that was driven by a metal coil wound by pulling the toy’s string. Her phrases were voiced by June Foray, also famous as the voice of Rocky the Squirrel in “The Rocky & Bullwinkle Show.” Newer versions of the doll sported a wider choice of hair and eye colors as well as an African-American version. By 1963, when this version of Chatty Cathy was introduced, she had long pigtails and her vocabulary had increased to 18 phrases.

According to director Josh Cooley, Gabby Gabby was based more directly upon an evil doll named Talky Tina, who appeared in a 1963 “Twilight Zone” episode. In this edge-of-your-seats episode, a family’s problems are made worse when a talking doll—which was loosely based upon Chatty Cathy and was also voiced by June Foray—develops a mind of her own and wreaks havoc on the family, inevitably leading to a tragic ending.

Page of doll carriages, Sears Roebuck & Co. Christmas Catalog, 1964. THF294577

As Woody and Forky search for Bo Peep in the quiet atmosphere of the antique shop, the sudden sound of a squeaky doll carriage edging closer but just out of view is one of the more hair-raising moments in the film. Sure enough, it reveals itself as Gabby Gabby’s mobility device and there is good reason for viewers to be nervous. Some of us have a visceral memory of those squeaky doll carriages of the mid-20th century, before safety and cost issues replaced the carriages’ metal and vinyl parts with plastic.

Doll carriages were generally based upon full-size baby carriages of their era. In the late 19th century, these were often quite elaborate, made of wicker with brass fittings and matching parasols and only affordable to the wealthy. As the 20th century progressed, pop-up tops, removable beds, and suspension systems made baby carriages more comfortable and convenient, and they also became more affordable to families of different economic levels. The three options shown in this 1964 Sears Roebuck Christmas catalog—of varying prices and materials—are all reminiscent of Gabby Gabby’s squeaky—and sneaky—doll carriage.

Doll Dessert Set, 1935-40. THF141192

In “Toy Story 4,” Gabby Gabby is delighted when the antique shop owner’s granddaughter, Harmony, sets up a toy tea set and pretends to take tea—hoping beyond hope that when her voice box is fixed, Harmony will invite her to join in.

Since the 19th century, miniature tea sets were a traditional way for little girls to practice adult skills and feminine roles. It was up to them, however, to decide whom to invite for company. Images, like the cover of this doll dessert set, often show little girls having tea with favored dolls and stuffed animals. Indeed, in previous “Toy Story” movies, we saw both neighbor Sid’s little sister and young Bonnie engage in this type of imaginative play. The strengthening of bonds between little girls and their dolls through pretend tea-drinking is something that Gabby Gabby desperately wants—so much so that she will resort to desperate measures to have it.

Charlie McCarthy Doll, 1937-40. THF106436

Without a doubt the creepiest characters in “Toy Story 4” are the Bensons—the group of ventriloquist dummies that Gabby Gabby enlists to do her bidding. Dating back to 18th-century traveling fairs, ventriloquists “threw” their voices to appear as if they were coming from elsewhere, usually a puppet or other semi-lifelike figure referred to as a dummy. During the early 20th century, Edgar Bergen popularized the idea of comedic ventriloquism, teaming up with his “cheeky,” boyish dummy, Charlie McCarthy. Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy became so popular that they appeared on “The Chase & Sanborn Radio Hour” from 1937 to 1956, as well as later films and TV programs. As shown here, Charlie McCarthy was reproduced by Effanbee as a child’s toy, complete with different outfits and a carrying trunk.

The Charlie McCarthy dummy and related doll were not intended to be evil (although some people would maintain that all ventriloquists’ dummies are creepy). Credit for that goes to the fact that the Bensons were more directly inspired by a series of “Goosebumps” books by R. L. Stine that began in 1993, featuring the villainous Slappy the Dummy. Though the book is from a later era, Slappy’s appearance recalls the ventriloquist dummies of Charlie McCarthy’s time. In “Toy Story 4,” the Bensons have no voices because there are no humans to provide them. And their bodies are soft with no structure because, without humans to operate them, their body parts just dangle. Very clever! And definitely creepy!

Will there be a “Toy Story 5”—with new toys, the return of familiar old toys, and a fresh spin on their interconnecting stories? Only time will tell.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

Disney, toys and games, popular culture, movies, by Donna R. Braden

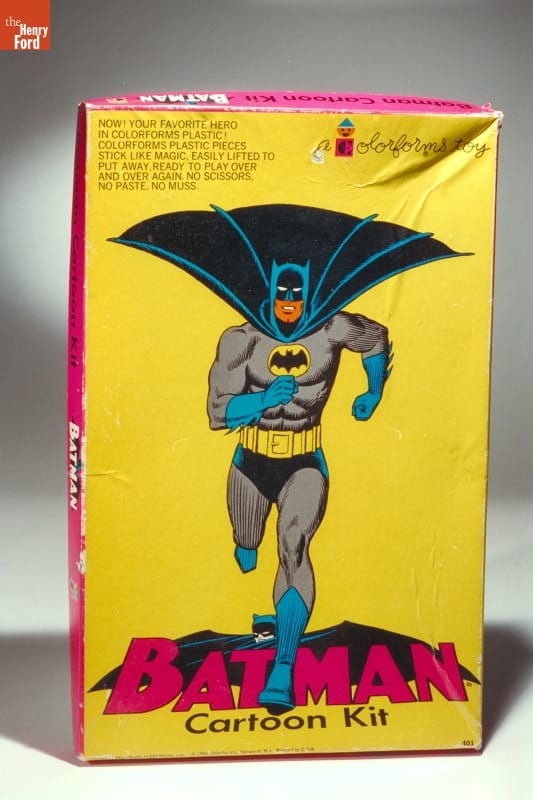

“Batman Cartoon Kit” Colorforms, 1966-68. THF 6651

It was the 1960s—the golden age of television. Some 95% of American homes boasted at least one TV. These were primarily black and white sets, as color TV was still out of the reach of many families. It’s hard to imagine now but there were only three channels at the time. Every year, the three networks (CBS, NBC, and ABC) vied for viewer ratings, shifting and changing shows and showtimes at two pivotal times during the television season—Fall and Winter.

As the Fall 1966 season unfolded, it became evident to TV viewers that something extraordinary was happening. Sure, there were the usual long-running sitcoms, like Green Acres, Petticoat Junction, and The Beverly Hillbillies. But change was in the wind. A new crop of programs emerged—colorful, fast-paced, poking fun at things that were supposed to be serious and exploring contemporary social issues.

Why the difference all of a sudden? Many of these shows were aimed at the youth audience, considered by this time an influential group of TV watchers. Others purposefully took advantage of the new color televisions. Sometimes show producers and creators were simply tired of the old formulas and wanted to break out of the box.

Let’s take a look at a few highlights from the 1966-67 TV season—starting with the staid and true and working up to the wild and wacky—and see what all the hubbub was about!

Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color (Sunday, 7:30-8:30 p.m., NBC)

Snow Globe, “The Wonderful World of Disney,” 1969-79. THF174650

On Sunday nights since 1954, millions of Americans had tuned in to watch Walt Disney host his TV show, with a changing array of animated and live-action features, nature specials, movie reruns, travelogues, programs about science and outer space, and—best of all—updates on Walt Disney’s theme park, Disneyland. Since 1961, this show had been broadcast in color.

The 1966-67 season was particularly memorable because Walt Disney tragically passed away on December 15, 1966. But since the episodes had been pre-recorded, there was Walt still hosting them until April 1967. Viewers found this both comforting and disconcerting. Finally, after April, Walt was dropped as the host and, eventually, the show was retitled The Wonderful World of Disney. It ran with solid ratings until the mid-1970s.

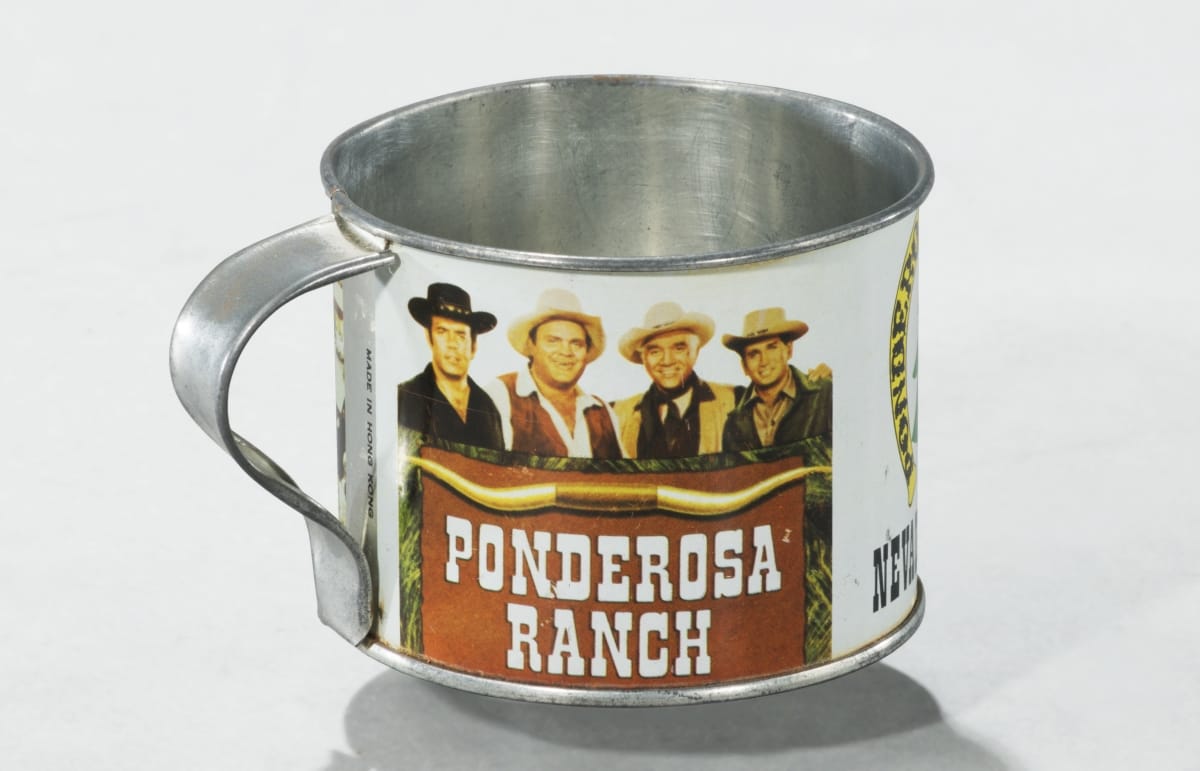

Bonanza (Sunday, 9:00-10:00 p.m., NBC)

“Ponderosa Ranch” Mug, ca. 1970. THF174648

Viewership was high on NBC on Sunday nights at 9:00, as Bonanza was one of the most popular TV shows of all time. Running for 14 seasons and 430 episodes, this series about the trials and tribulations of widower Ben Cartwright and his three sons on the Ponderosa Ranch was an immediate breakout hit when it premiered in 1959, amidst a plethora of more run-of-the-mill prime-time westerns. Its popularity was primarily due to its quirky characters and unconventional stories—including early attempts to confront social issues. It was the first major western to be filmed in color and was the top-rated show on TV from 1964 to 1968. Bonanza ran until 1973.

The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (Friday, 8:30-9:30, NBC)

“The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” lunchbox and thermos, 1966. THF92303

Premiering in September 1964, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. took full advantage of the popularity of the spy genre launched by the James Bond film series. In fact, early concepts for it were conceptualized by Bond creator Ian Fleming. In this series, Napoleon Solo (originally conceived as the lone star) and Russian agent Ilya Kuryakin (added in response to popular demand) teamed up as part of a secret international counterespionage and law enforcement agency called U.N.C.L.E. (United Network Command for Law and Enforcement). Solo and Kuryakin banded together with a global organization of other agents to fight THRUSH, an international organization that aimed to conquer the world.

During this, the Cold War era, it was groundbreaking for a show to portray a United States-Soviet Union pair of secret agents, as these two countries were ideologically at odds most of the time. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was also known for its high-profile guest stars and—taking a cue from the Bond films—its clever gadgets. In 1966, this series won the Golden Globe for Best Television Program and, building upon its popularity, spun off into two related double-feature movies that year. Unfortunately, attempting to compete with lighter, campier programs of the era, the producers made a conscious effort to increase the level of humor—leading to a severe ratings drop. Although the serious plot lines were soon reinstated, the ratings never recovered. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was canceled in January 1968.

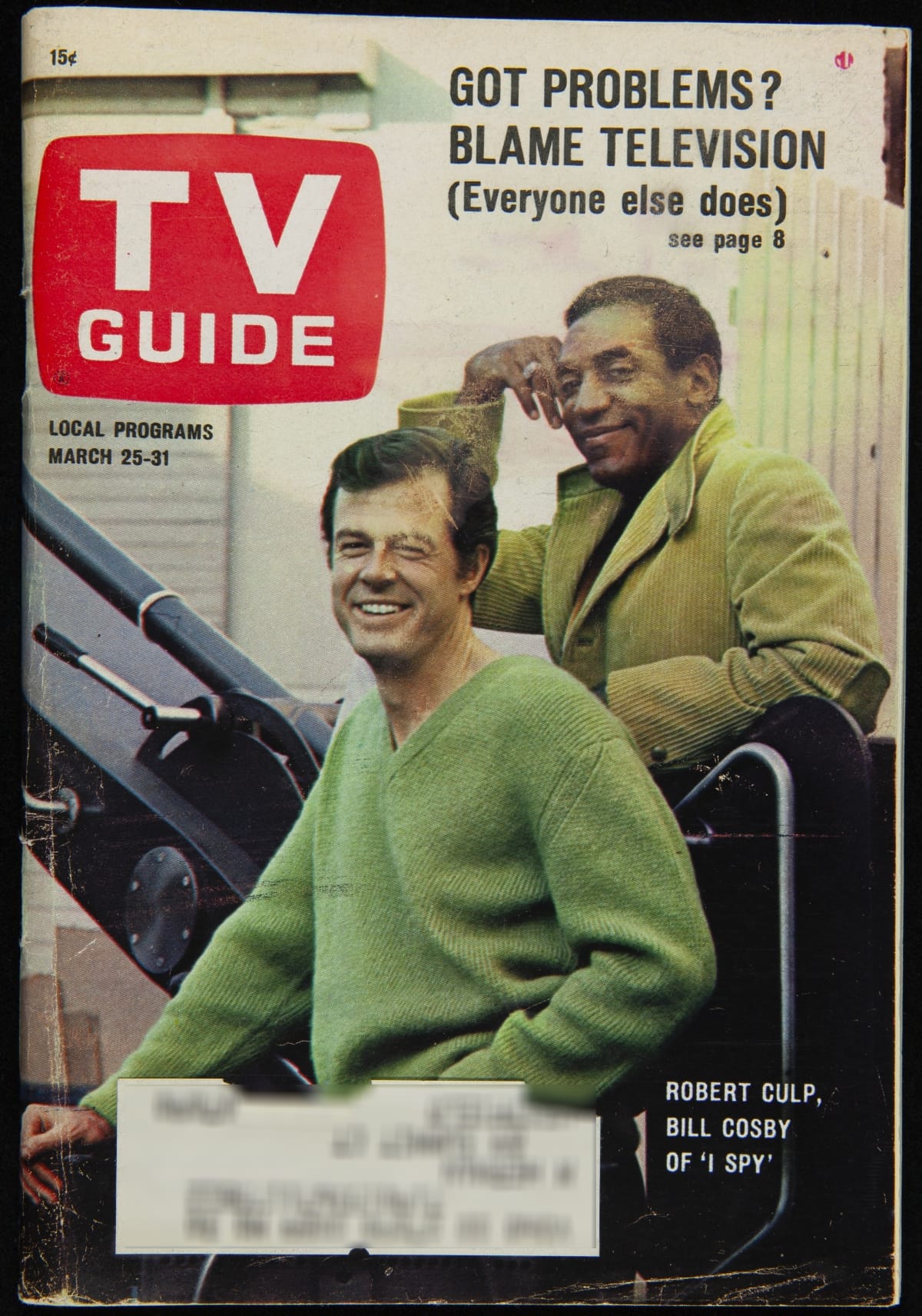

I Spy (Wednesday 10:00-11:00, NBC)

TV Guide featuring “I Spy” characters Robert Culp and Bill Cosby on cover, March 25-31, 1967. THF275655

One series that never opted for campy was I Spy, which starred Bill Cosby and Robert Culp playing two U.S. intelligence agents traveling undercover as international “tennis bums.” This series, which premiered in 1965, was also inspired by the James Bond film series and remained a fixture in the secret agent/espionage genre until cancelled in April 1968. I Spy, additionally a leader in the buddy genre, broke new ground as the first American TV drama series to feature a black actor in a lead role. It was also unusual in its use of exotic locations—much like the James Bond films—when shows like The Man from U.N.C.L.E. were completely filmed on a studio backlot.

I Spy offered hip banter between the two stars and some humor, but it focused primarily on the grittier side of the espionage business, sometimes even ending on a somber note. The success of this series was attributed to the strong chemistry between Culp and Cosby. Cosby’s presence was never called out in the way that black stars and co-stars were made a big deal of on later TV programs like Julia (1968) and Room 222 (1969).

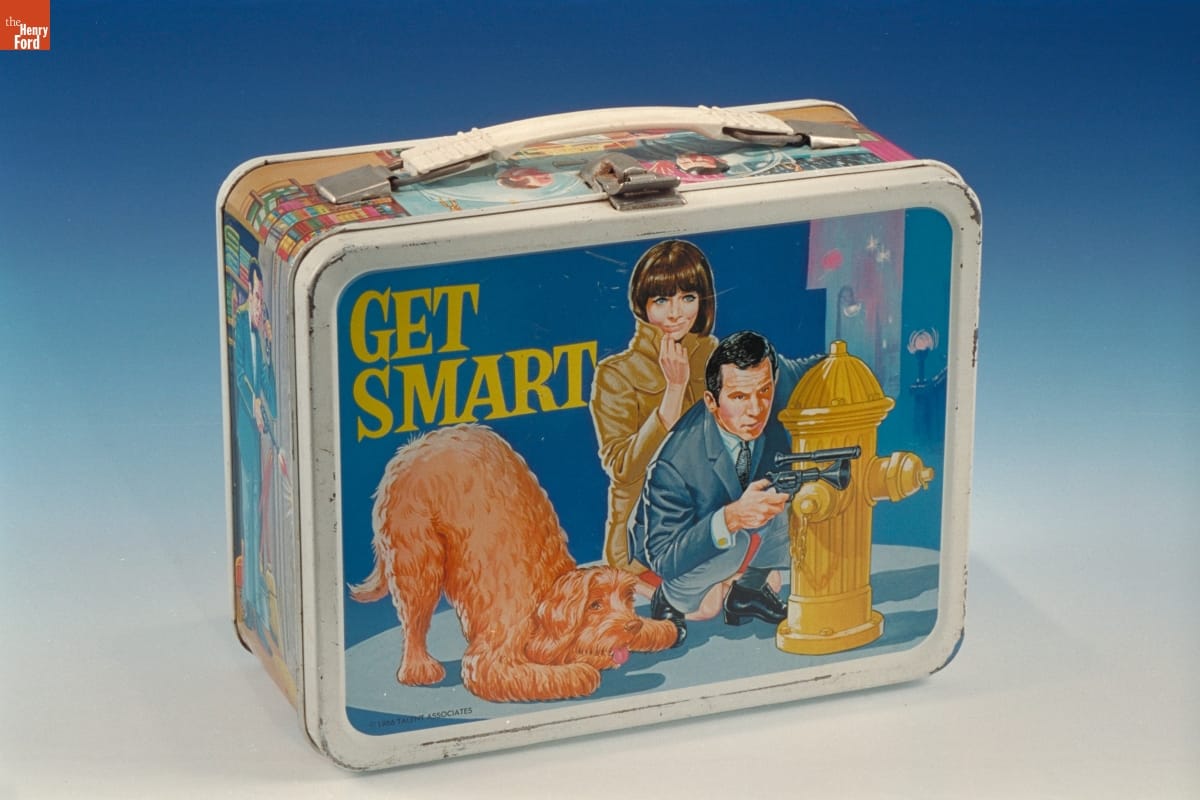

Get Smart (Saturday, 8:30-9:00 NBC)

“Get Smart” Lunchbox, 1966. THF92304

Premiering in September 1965, Get Smart was a comedy that satirized virtually everything considered serious and sacred in the James Bond films and such TV shows as I Spy and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Created by comic writers Mel Brooks and Buck Henry as a response to the grim seriousness of the Cold War spy genre, it starred bumbling Secret Agent 86—otherwise known as Maxwell “Max” Smart, along with supporting characters, female Agent 99 and the Chief. These characters worked for CONTROL, a secret U.S. government counterintelligence agency, against KAOS, “an international organization of evil.” Brooks and Henry also poked fun at this genre’s use of high-tech spy gadgets (Max’s shoe phone perhaps being the most memorable), world takeover plots, and enemy agents. Somehow, despite serious mess-ups in every episode, Maxwell Smart always emerged victorious in the end.

Get Smart was considered groundbreaking for broadening the parameters of TV sitcoms but was especially known for catchphrases like “Would you believe…” and “Sorry about that, Chief.” Despite a declining interest in the secret-agent genre, Get Smart’s talented writers attempted to keep it fresh until it was finally cancelled in May 1970.

Batman (Wednesday and Thursday, 7:30-8:00, ABC)

Toy Batmobile, 1966-69. THF174647

Bursting onto the scene in January 1966, Batman became an instant hit and took the country by storm. Batmania was in full swing by the Fall 1966-67 TV season. The series, based upon the DC comic book of the same name, featured the Caped Crusader (millionaire Bruce Wayne in his alter-ego of Batman) and the Boy Wonder (his young ward Dick Grayson in his alter-ego of Robin). These two crime-fighting heroes defended Gotham City from a variety of evil villains. It aired twice weekly, with most stories leaving viewers hanging in suspense the first night until they tuned in the second night.

This show successfully captured the youth audience, with its campy style, upbeat theme music, and tongue-in-cheek humor. Despite the fact that it verged on being a sitcom, the producers wisely left out the laugh track, reinforcing the seriousness with which the characters seemed to take the often absurd and wildly improbable situations in which they found themselves. The filming simulated a surreal comic-book quality, with characters and situations shot at high and low angles, with bright splashy colors and with sound effects, like Pow, Bam, and Zonk, appearing as words splashed across the action sequences on screen. The series was also replete with numerous gadgets and over-the-top props, with the Batmobile undoubtedly most memorable. Batman ran until March 1968, experiencing a significant ratings drop after its initial novelty faded.

Lost in Space (Wednesday 7:30-8:30, CBS)

“Lost in Space” Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967. THF92298

Loosely based upon the story of the Swiss Family Robinson, this TV series depicted the adventures of the Robinson family, a pioneering family of space colonists who struggled to survive in the depths of space in the futuristic year of 1997—as the United States was gearing up to colonize space due to overpopulation. But the family’s mission was sabotaged, forcing the crew members to crash-land on a strange planet and leaving them lost in space.

The show had premiered in September 1965 as a serious science fiction series about space exploration and a family searching to find a new place for humans to dwell. But, in January 1966, pitted against Batman’s time slot, Lost in Space producers attempted to imitate Batman’s campiness with ever-more-outrageous villains, brightly colored outfits, and over-the-top action. The plots increasingly featured Robby the Robot and the evil Dr. Zachary Smith. Viewers and actors alike strongly disapproved of this shift. The show lingered on until March 1968.

The Monkees (Monday, 7:30-8:00, NBC)

“Monkees” Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967. THF92313

Where other shows might have been lighthearted, campy, or tongue-in-cheek, The Monkees at times verged on pure anarchy. This series, which premiered on September 12, 1966, led off NBC’s prime-time programming every Monday night. It lasted only two seasons but during that time, its star shone brightly. The Monkees followed the experiences of four young men trying to make a name for themselves as a rock ‘n’ roll band, often finding themselves in strange, even bizarre, circumstances while searching for their big break. Aimed directly at the youth audience, the band members were characterized as heroes down on their luck while the adults were consistently depicted as the “heavies.”

The Beatles’ films A Hard Day’s Night and Help! inspired producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider to create not only a show about a rock ‘n’ roll band but also to adapt a loose narrative structure (each member of the Monkees was trained in improvisational acting techniques at the outset of the show) and the musical sequences or “romps” that appeared each week. The series built a reputation for its innovative use of avant-garde filming techniques like quick jump cuts and breaking the fourth wall (that is, having the characters directly address the TV viewers). A well-oiled marketing machine behind the show also ensured that strong tie-ins were maintained with teen magazines, merchandise, and live concerts.

The Monkees won the Emmy for best comedy series during its first, the 1966-67, season. However, backlash was inevitable among critics and older teenagers when the Monkees admitted that they did not play their own instruments—although they clearly played them in their live concerts and, in fact, eventually had a falling-out with network executives about this very issue. Though the show was cancelled in 1968, it experienced a huge revival among younger audiences through Saturday morning reruns and especially with the 1986 MTV Monkees Marathon. Remaining band members Micky Dolenz and Mike Nesmith still attract large audiences of intergenerational fans at their live concerts, while reruns of their TV shows continue to draw new audiences.

Star Trek (Thursday, 8:30-9:30 NBC)

“Star Trek” lunchbox, 1968. THF92299

When Star Trek premiered on September 8, 1966, science fiction shows were not very advanced—or even thought of very highly. Star Trek’s closest competitor, Lost in Space, offered only shallow plots, one-dimensional characters, and fake sets. No one could imagine at the time that this rather low-key show would become one of the biggest, longest-running, and highest-grossing media franchises of all time. This series traced the interstellar adventures of Captain James T. Kirk and his crew aboard the United Federation of Planets’ starship Enterprise, on a five-year mission “to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before.”

Creator Gene Roddenberry, aiming the show at the youth audience, wanted to combine suspenseful adventure stories with morality tales reflecting contemporary life and social issues. So, to get by network scrutiny, he set the premise of the show in an imaginary future. With the freedom to experiment, he put in place one of TV’s first multiracial and multicultural casts and was able to explore through different episodes some of the most relevant political and social allegories on TV at the time. The stories were also considered exceptionally high quality for that era, involving believable characters with which viewers could both identify and sympathize. Unlike the gloomy predictions of most science fiction writings of the time, Roddenberry hoped that the futuristic utopia he created on Star Trek would give young people hope, that it would empower them to create a better future for themselves someday. Star Trek, with only modest ratings, lasted only three seasons. But it would go on to become a cult classic.

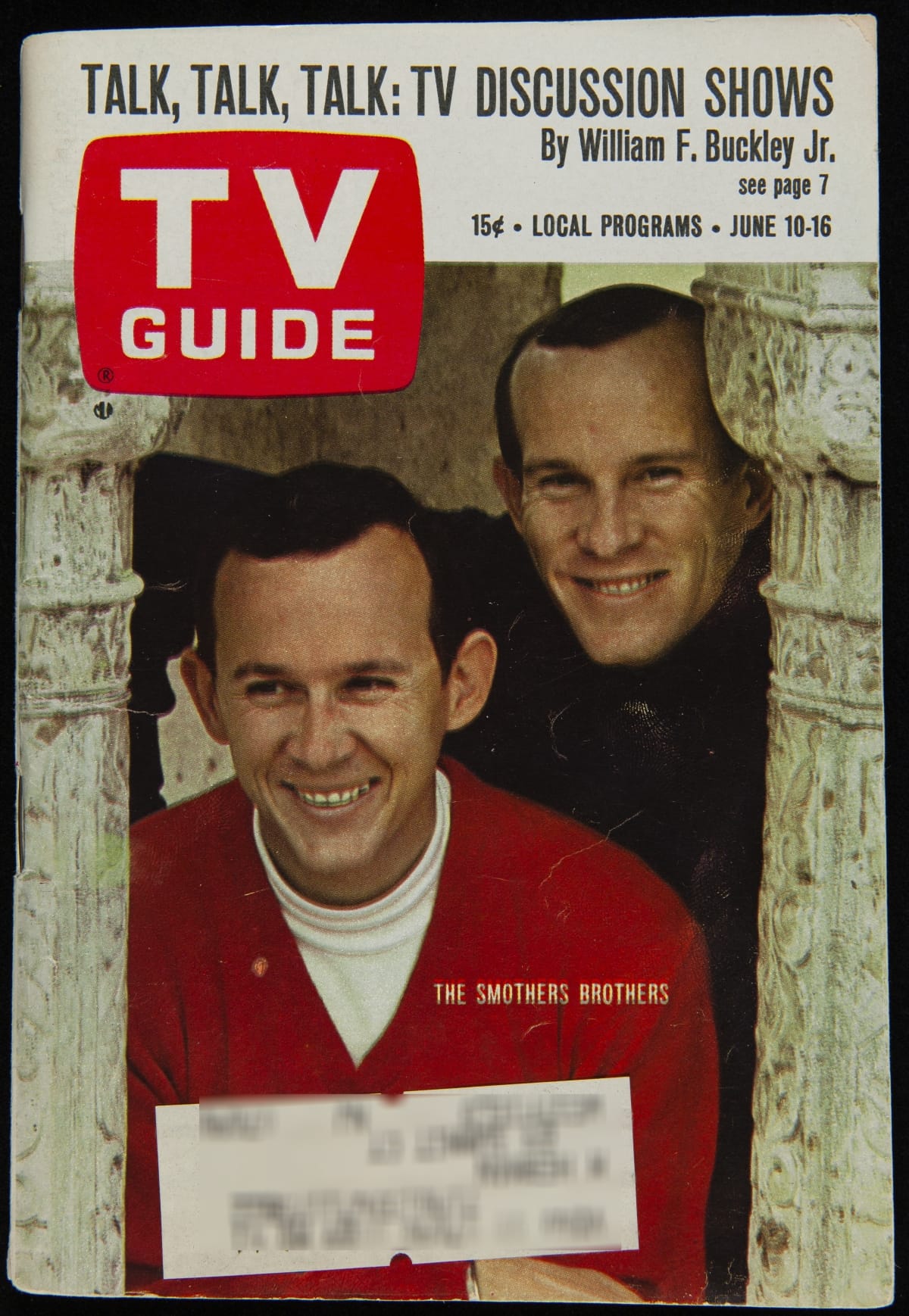

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (Sunday, 9:00-10:00 p.m. beginning February 1967, CBS)

TV Guide featuring The Smothers Brothers on cover, June 10-16, 1967. THF275657

In Fall 1966, The Garry Moore Show, a variety show on CBS hosted by the aging radio and TV star, was no match when pitted against Bonanza—even with this, its first season in color. Network executives, at their wit’s end to try to attract viewership, decided the only way they could come up with a quick replacement was to substitute another variety show. In desperation, they landed on a simple variety series featuring the soft-spoken, clean-cut, non-threatening folk-music-playing Smothers Brothers. Considered a “young act,” an added bonus was that their show might capture the coveted youth audience. Little did they know what they were in for.

As the show evolved, the brothers not only became more politicized themselves but felt that they owed it to their young viewers to increase the show’s relevance, boldly addressing overtly divisive political and social issues. Their staff of young writers was only too happy to comply. Unfortunately, as a result, the brothers were continually at odds with the network censors until the show was finally cancelled after three seasons. In its continual conflicts with network executives, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour turned the variety show genre on its ear and paved the way for Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1968) and, in pushing TV’s all-out rebellion against the status quo, led an explosive charge that resulted in 1970s shows like All in the Family (1971).

These are but a few highlights from the 1966-67 TV season. Some say that this was the greatest television season ever, a clear indication that TV had finally come of age. Because of shows like these, television would certainly never be the same again. And, come to think of it, neither would we!

Donna Braden, Curator of Public Life, was 13 years old during that memorable TV season and proudly wears her fan club button to every Monkees concert she still attends.

20th century, 1960s, TV, Star Trek, space, popular culture, music, Disney, by Donna R. Braden

The Real Toys of “Toy Story”

Sliding puzzles of Toy Story characters, 1996. THF135833, THF135835

Sunday November 22, 2020, is the 25th anniversary of Disney-Pixar’s first Toy Story movie, which came out in 1995. Learn about the real history of toys that inspired the characters in this hit animated film.

In 1995, Disney-Pixar’s Toy Story made history as the first feature-length computer-animated film. The movie was a surprise box-office hit, far exceeding estimates. In 1996, it won an Academy Award for Special Achievement and was the first animated film ever nominated for Best Original Screenplay.

In fact, Disney took a real chance on Pixar, a young unproven tech startup at the time. Indeed, the staff at Pixar knew computer technology but they had never created a full-length feature film. But, in the course of developing the film, they made a key decision that laid the foundation for Pixar’s success, both then and now. They decided to put the story first—to focus attention the characters, the plot, the action. So, sure, the computer animation of the first Toy Story movie looks really primitive today. But pretty soon, you forget about that because the story still grabs you. Even though the main characters are toys, it’s a universal human story, about who your friends are, or aren’t, or could be.

In addition to the very relatable human story, both children and adults embraced the film right from the beginning because of the choices of the toys themselves. Why are those the toys in Andy’s room? In fact, they primarily come from the filmmakers’ own memories playing with their childhood toys—leading to a motley assortment of toys from the mid-20th century to the 1990s that reflects the varied ages of the film’s creators. Some of these evoke a specific era; others have become classics, continually produced over decades for successive generations of kids. We dug into our own collections to find some of the real toys that appear in Toy Story and reveal their true stories.

Sheriff Woody: Cowboy Toys

Cheyenne game, 1958-65. THF 91876

Let’s start with the main character, Sheriff Woody. Woody wasn’t a real toy; instead, he represented a whole group of toys. During the 1950s, cowboy movies and TV shows were huge. This was an era during which the West was greatly romanticized, something Walt Disney was on to when he created Frontierland at Disneyland in 1955. Cowboys, in particular, were revered as rough and tough, independent, honest, and hardworking characters—at the time considered laudable traits for young boys (and girls) to emulate. In Toy Story 2, we find out that Woody indeed comes from a 1950s-era TV show entitled Woody’s Roundup. This game from our collection was named after a real TV show called Cheyenne that ran from 1955 to 1963.

Buzz Lightyear: Outer Space Toys

Rocket Darts game, 1940s. THF 91902

Buzz Lightyear also represented an era and a larger group of toys and games. During the mid-20th century, outer space was considered really mysterious and it fascinated people. At first, it was depicted as pure science fiction, as represented by the aliens and Pizza Planet in Toy Story and shown on the cover of this Rocket Darts game from the 1940s. Increasingly, outer space became a real destination as part of the 1960s-era “Space Race”—leading to Americans actually landing a man on the moon in 1969. Buzz Lightyear is reminiscent of this era, equipped as he is with special features that seem more advanced and sophisticated than Woody’s primitive pull string.

Mr. Potato Head

Mr. Potato Head playset, 1955-60. THF 47

Mr. (and Mrs.) Potato Head were and still are real toys. They were introduced in 1952 and 1953, respectively. Back in the 1950s, when this playset was produced, it included 28 different face pieces and accessories—like eyes, noses, mouths, and mustaches—that kids would stick on real potatoes! Hasbro began supplying a plastic potato with each kit in 1964.

Slinky

Life magazine ad, 1957. THF 109573

Slinky in original box, 1970s. THF 309090

Slinky Dog or, as Woody called him—“Slink”—was also a real toy, as show in this 1957 Christmas ad. He evolved from the invention of the Slinky, along with a host of other rather bizarre-looking Slinky-related toys shown in this ad. The original Slinky was introduced in 1946, when a marine engineer was trying to invent a spring for the motor of a naval battleship.

Toy Soldiers

Toy army men, mid- to late 20th century. THF 170098

The green army men from the “Bucket O Soldiers” referenced the long history of toy soldier playsets. Toy soldiers made of lead or tin date back to the 19th-century Europe. With advancements in plastics, green army men made of plastic like these became popular after World War II. Molding these figures in one piece with the base attached was less expensive to manufacture, leading to the stiff-legged maneuvers of the “troops”—as Woody called them—in the film.

Doodle Pad: Magic Slate and the Magna Doodle

Magic Slate, 1937-46. THF 135603

Woody’s Doodle Pad may be a mashup between the Magic Slate and the Magna Doodle. The Magic Slate, marketed as the “erasable blackboard” is essentially a cardboard pad covered with a clear plastic sheet that “wrote” when a wood or plastic stylus was impressed on it and “erased” when the plastic was lifted up. It dates back to the 1920s, when it was offered as a free giveaway by a printing company. People finally realized that it would make a great plaything and it was heavily marketed to kids after World War II. The Magna Doodle, introduced in 1974 as a “dustless chalkboard,” can be considered a later magnetic version of the Magic Slate, with an erasable arm that swept the “board” clean.

Etch A Sketch

Etch A Sketch, 1961. THF 93827

The Etch A Sketch fell somewhere between the Magic Slate and the Magna Doodle. It was invented in 1958 by a French mechanic and tinkerer, who called it “L’Ecran Magique,” or “The Magic Screen.” It used a mixture of aluminum powder and plastic beads with a metal stylus guided by twin knobs and it erased when it was turned over and shaken. The rights to the toy were sold to Ohio Art in 1960, where it became the company’s biggest hit.

Barrel of Monkeys

Barrel of Monkeys game, 1966-70. THF 91975

What better way to use the Barrel of Monkeys game than to make a chain of monkeys to try and save a toy that had fallen out of a second-story window? Unfortunately, the monkeys didn’t save Buzz Lightyear but, when this game was introduced in 1966, it was advertised as being—what else?—“more fun than a barrel of monkeys.”

TinkerToys

Junior TinkerToy for Beginners playset, 1937-46. THF 135602

Woody used the classic TinkerToy box as a lectern for his meeting with the other toys in Andy’s room. TinkerToys were the brainchild of a man who cut out tombstones for a living but saw how much fun kids were having sticking pencils into spools of thread. He came up with the idea of the TinkerToy playset in 1914, billing it as the “Thousand Wonder Builder.” Over the years, TinkerToys were produced in a huge array of colors, sizes, and variations including plastic sets for younger kids introduced in 1992.

Bonus “Toy:” Nursery Monitor

Playskool Portable Baby Monitor, circa 1990. THF170094

The Nursery Monitor is technically not a toy, but it played a key role in the “Toy Story” film for the troops’ reconnaissance mission to report out on Andy’s presents. So we’ll consider it an honorary toy. It is the only item here, and one of the very few in the film, that dates uniquely from the era of Andy’s own childhood. This device would have connected immediately with young viewers who were Andy’s age in 1995, and who would grow up with him in succeeding Toy Story films.

Donna R. Braden, Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford, enjoyed viewing Toy Story several times as “research” for this blog post.

This post was last updated November 18, 2020.

20th century, 1990s, toys and games, popular culture, movies, Disney, by Donna R. Braden