Posts Tagged entrepreneurship

Unpacking the History of Labels

Crate Label, “Far West Brand Pears,” circa 1930 THF293059

As Project Curator for the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship, I research objects within The Henry Ford’s collections that tell entrepreneurial stories. Most recently, I delved into the Label Collection, which includes labels from alcoholic beverages, cigar boxes, medicines, various food related items, and miscellaneous products. This blog post highlights the West Coast fruit crate labels and canned food labels.

Label Lithography

Can Label, “Defender Brand Tomatoes,” 1913-1918 THF293393

In the late 1800s, the preferred method of printing used to make image-centric labels like these was lithography. This process involved the transfer of an inked image from stone or metal plates to paper via a printing press. Skilled artists drew their images on flattened, smooth pieces of stone – traditionally limestone – to then be inked and transferred. Later, flexible, photosensitive metal plates were used on rotary and offset presses, making the lithographic process more efficient. The artists who worked in this medium were called lithographers. Some of the growers, as well as some of the packing and distribution companies, had their own lithography departments to produce labels. The majority, however, hired lithography companies to create their label designs.

The introduction of color into the lithography process, known as chromolithography, transformed the advertising industry. Multi-colored lithographs involved several transfers of the same image from multiple stones, or plates, each with their own color ink in the desired layout. The more colors included in the image, the more transfers (and stones/plates) required to produce the desired result.

Crate Label, “Atlas Brand Blackberries,” 1916-1930 THF113854

This label for Atlas Brand Blackberries is an example of single-color lithography and was produced through a single ink pass. The shading and variation seen in this image was created by the methods of stippling, linework, and applying different densities of the same color of ink to the page. The stippling method refers to the pattern of dots, which can be seen if you look closely at the fruit depicted on this label.

Can Label, “Holly Brand Peaches,” circa 1916 THF293047

To enhance the attractiveness of a label some lithographers incorporated metallic pigments and dimensional, embossed areas into their designs. Metallic pigments created the shiny golden appearance that can be seen along the edges of this label for Holly Brand Yellow Cling Peaches.

Fruit Crate Labels

Before the 1860s, East and West Coast markets were essentially isolated. Because of differing climates, certain produce was only available to consumers living in the eastern United States during specific seasons while most produce in the West could be grown throughout the entire year. When the transcontinental railroad opened in 1869, eastern markets were opened to the West Coast produce industry for the first time. The railroad, along with the growing canning industry, allowed consumers to enjoy fruits and vegetables year-round – encouraging the establishment of more growers and packing companies in the West to meet the high demand. By the turn of the century and into the early twentieth-century, California fruit growers provided an abundance of fresh fruit to the national markets, transforming the American diet.

With greater competition among growers and packing houses, the crate label became an important marketing tool. At the time, grocers were the link between customers and the products. Grocers obtained their goods from wholesale markets, choosing their products by price and intuition. The label had to stand out and appeal to the grocer who would then buy several crates of the product and sell it in his store. If the grocer heard that customers liked a certain brand over previous ones he’d supplied, he could make sure to purchase that particular brand again, using the crate label for identification.

These fruit crate labels are often stunningly beautiful – more like mini-posters with broad color palettes, incredibly detailed images, and clever brand names. A common feature of label design was an image of where the fruits and vegetables were produced. Customers became enamored with the shining groves of oranges in the West and came to identify certain places with the best produce. Other labels feature popular motifs of the time and allow us to explore the trends in graphic design.

Crate Label, “Orchard Brand Pears,” circa 1920 THF293065

California wasn’t the only state on the West Coast to produce delicious fruit. Washington was known for its many varieties of apples as well as other fruits, including pears.

Crate Label, “Bocce Brand Zinfandel Grapes,” circa 1940 THF293043

C. Mondavi & Sons’ “Bocce” label played up the family’s Italian roots, aligning its product with the quality grapes grown in Italian vineyards. This successful business was established by Cesare Mondavi, a Minnesota grocer and saloon owner who often traveled to California to select and ship grapes back home to make his own wine. After becoming enamored with the California climate, which reminded him of Italy, he moved his family to Lodi in 1923 to open a business growing and shipping grapes. His success allowed him to purchase a winery in 1946, which is still thriving today as C. K. Mondavi and Family.

Crate Label, “Santa Rosa Brand Ventura County Lemons,” copyright 1927 THF293109

This label features the sprawling lemon groves in Oxnard, California. It also features the “Sunkist” logo, which became a popular brand known for its high-quality oranges and lemons.

Canned Food Labels

The process of canning food has been around since the early 19th century, with products used as wartime provisions for French and British armies. Tin cans allowed food producers to safely transport their goods without fear of them breaking – as was common with glass jars and bottles – making cans a more economical container for foodstuffs. While canned foods were introduced to America by the 1820s, the demand for these products came four decades later during the American Civil War.

Unlike glass jars or bottles, which allowed consumers to view the product inside, cans required identification. At first, labels were simply a tool to inform the customers of the product they were buying, who produced it, and where it was produced. As railroad networks expanded in the late 1800s and competition increased, more elaborate labels were created to appeal to customers in new markets across the country. The label became even more important after World War I when customers began selecting products for themselves in self-service grocery stores.

Can Label, “Butterfly Brand Golden Pumpkin,” 1880-1895 THF113859

Can Label, “Butterfly Brand Golden Wax Stringless Beans,” circa 1885 THF113860

Using the same design for several different products became a strategy for helping customers find the brand with which they were familiar. Olney and Floyd’s Butterfly Brand products were easy to identify with their colorful, eye-catching labels and signature butterfly.

Can Label, “Bare Foot Boy Brand Tomatoes,” circa 1910 THF293079

Characters were a common feature in product advertising. The goal was to create an emotional or personal connection between the product and the customer – a practice that is still seen in marketing strategies today.

Can Label, “Lynx Brand Puget Sound Salmon,” 1880-1900 THF109742

As canned goods made their way across the country, certain states became known for specific products. Washington, for instance, was known for its salmon industry and canned salmon was shipped from the Pacific Northwest all across the United States. This beautiful label was created by the Schmidt Lithograph Company – one of the most well-known companies in the lithography industry.

If you enjoyed this small sample of labels, visit our Digital Collections to see other fruit crate labels and canned food labels in our collection.

Samantha Johnson is Project Curator for the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship at The Henry Ford.

shopping, by Samantha Johnson, advertising, communication, technology, printing, food, entrepreneurship

The Secret Life of a Heinz Recipe Book

As Project Curator for the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship, part of my job is to select items related to entrepreneurs within our collection to be digitized. Sometimes this calls for additional research to provide context and significance. Searching for the significance of an object or photograph can often feel like detective work. Sometimes we are able to do some sleuthing and find what we are looking for and other times we run out of leads. Recently, while working with the H. J. Heinz Company Records – the first archival collection selected for this project – we had the opportunity to dig deeper into the significance of a notebook and learn more about its owner.

This notebook containing hand-written recipes from the H. J. Heinz company has been on display at the Heinz House in Greenfield Village for the past several years. Upon getting a closer look, we discovered that there was a name written on the outside: Jn Koehrer.

The cover of the notebook states that it belongs to Jn Koehrer.

Who was this Jn (John) Koehrer? Unaware of any immediate connections to H. J. Heinz, we turned to Ancestry.com, where we discovered that John Koehrer (1871-1945) was listed as a foster son of Heinz’s cousin, Frederick Heinz. Census records noted that he worked for a “Pick Co.” – which we assumed was supposed to say “Pickle Co.” – and that his occupation was that of a “pickler” or a “foreman.” So now we have a connection to H. J. Heinz, but what does his notebook have to do with the company history?

A Google search for “‘John Koehrer’ Heinz” led us to our answer. An Architectural and Historical Survey of Muscatine, Iowa, noted that, “On January 29, 1893, the Muscatine Improvement and Manufacturing Company closed the contract with Heinz to build its first plant outside of Pittsburgh… The three-story brick building… Opened in 1894 under the management of John Koehrer.” There it was! – the reason he had a notebook of recipes, and why it was significant to company history, was because he was to manage the new Heinz factory and needed to make sure he could replicate the products.

Handwritten recipe from the notebook for “Chilli Sauce.” Half-way down the page you’ll notice that the recipe calls for “1/2 pound of xxx.” The three x’s can be found in other recipes too and represent a secret ingredient.

Additional research from online newspaper articles allowed us to discover what was primarily produced at the plant – sauerkraut, horseradish, pickles, ketchup, and other tomato products – and we inferred that the recipes within the notebook would have been fairly simple to produce at the factory. From previous conservation and cataloguing reports, we had dated the notebook to around 1890, which fit perfectly into the timeline for John to have used these recipes in Iowa.

With this new information we are now able to more accurately describe the notebook on display and the research we uncovered can be added to our records for future use. When it comes to historical research, you never truly know what you’re going to find. In this digital age, and with more resources at our fingertips than ever before, more hidden gems like this one can be uncovered – a joy to behold in the history field.

Samantha Johnson is Project Curator for the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship at The Henry Ford. Special thanks to Aimee Burpee, Associate Registrar – Special Projects, for helping us uncover the mystery behind this notebook!

19th century, research, recipes, Heinz, food, entrepreneurship, by Samantha Johnson, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Exploring Entrepreneurship

Many experts describe entrepreneurship as the act of launching and managing a business venture. Those who establish these businesses are called entrepreneurs – but what does it really mean to be an entrepreneur?

The Parker Brothers honed their own entrepreneurship skills as they became a household name in the board game industry. Their “Make-a-Million” was a card game from the 1930s in which teams competed to win “tricks,” vying to become the first to reach one million dollars. THF91890

With the recent launch of the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship, The Henry Ford hopes to become a recognized resource for the next generation of entrepreneurs and innovators. Through a $1.5 million grant, the institution-wide initiative will support the creation of a Speaker Series, youth programming, workshops, and Innovation Labs, which focus on cultivating an entrepreneurial spirit for the entrepreneurs of today and tomorrow. Additionally, four Entrepreneurs in Residence (EIRs) – beginning with local urban farmer Melvin Parson – will foster entrepreneurial learning for both youth and adults by engaging the EIR’s expertise in a project that connects The Henry Ford and the broader entrepreneurial community. Lastly, as a part of its commitment to connecting to and inspiring future entrepreneurs, the Initiative for Entrepreneurship will highlight the entrepreneurial stories within our collections. As Project Curator, I will work with Project Collections Specialist-Cataloger Katrina Wioncek and Project Imaging Technician Cory Taylor, as well as other staff from The Henry Ford, to identify and provide access to these stories through our Digital Collections and related content, including blog posts like this one.

The Henry Ford’s founder and namesake is one of the best-known American entrepreneurs. Persisting through multiple failures, Ford revolutionized the automotive industry and built a lasting enterprise in the Ford Motor Company. This 1924 photograph shows Ford posing in front of his first automobile – the 1896 Quadricycle – and the ten-millionth Model T to roll off the assembly line. THF113389

When I joined the project in January, my first task was to define “entrepreneur.” This proved to be challenging, as a simple Internet search produced dozens of definitions and interpretations. I soon discovered that the reason for the discrepancy is that there are several different categories of entrepreneurship, but the many sources I referenced agree on two points: all entrepreneurs launch and manage their own business and take on financial risks in creating that business.

Harvey Firestone was an entrepreneur in the tire making business, building the global brand Firestone Tire and Rubber Company. Here Henry Ford and Firestone observe an experimental watering system at Firestone Farm in Columbiana, Ohio in 1936. THF242526

Entrepreneurs can range from small business owners hoping to provide for their families to industry millionaires who head up large companies. There are also social entrepreneurs who seek to solve a local problem or large social enterprises hoping to save the world. The differences lie within their motivations and how they measure success. While most entrepreneurs are in the business to make a profit, social entrepreneurs have the goal of generating funds to contribute to a particular cause or solving a social problem. For-profit entrepreneurs measure success based on revenue or stock increases, while social entrepreneurs can be a blend of for-profit and non-profit agendas, assessing their impact on society while still generating revenue.

Social entrepreneur Lauren Bush Lauren was the first speaker in the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship Speaker Series. Lauren spoke about her business, FEED Projects, which seeks to tackle world hunger. Proceeds from her line of handbags and accessories provide meals to schoolchildren around the globe.

Throughout the two-year initiative we will highlight stories from our rich and varied collections that demonstrate the characteristics that entrepreneurs share. To name a few, entrepreneurs are creative thinkers, resourceful, passionate, highly motivated, willing to take risks, and able to persevere through hardship.

The Wright Brothers were fantastic inventors – their greatest invention being the first powered, controlled airplane. But the Wrights were better inventors than entrepreneurs as they never found great success in the manufacture or sale of their airplanes. An entrepreneur is tenacious and will do whatever it takes to see their plan through, regardless of setbacks and barriers. THF112405

Henry J. Heinz transformed the eating habits of late 19th– and early 20th—century America. He was passionate about providing a quality product and supported a strong working relationship with his employees. Here Heinz is in a cucumber field encouraging and motivating his workers. THF275188

The first six months of the initiative will focus on Social Transformation within Agriculture and the Environment – two of our collecting areas that encompass transformative social change in the history of how we grow and experience food. In addition to digital content and other programs created by the grant, local urban farmer and social justice activist Melvin Parson will serve as our first Entrepreneur in Residence, allowing us to connect these ideas to our community. Stay tuned over the next several months as we digitize related archival material and publish new entrepreneurial digital content!

Samantha Johnson is Project Curator for the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship at The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Small Objects with Big Stories

Timber Scribe: A small tool, a timber scribe, helps inform us about resourcefulness and entrepreneurship.

Timber Scribe: A small tool, a timber scribe, helps inform us about resourcefulness and entrepreneurship.

The Oxford English Dictionary confirms use of the term “timber scribe” by 1858 as “a metal tool or pointed instrument for marking logs and casks.” Another tool, a “race-knife” (also spelled rase knife) performed a similar function, “marking timber,” but the tools differed in detail.

The race knife had a “bent-over, sharp lip for scribing,” according to Edward H. Knight who compiled the Practical Dictionary of Mechanics, a nearly 8,000-page behemoth containing 20,000 subjects and around 6,000 illustrations, published in 1877. The timber scribe included two pieces with bent-over sharp lips as well as a point. The combination made it possible to scribe Arabic numbers, not just gouge Roman numerals, into logs and casks and timber, as shown below.

This tool has a wooden handle, a brass band that helped stabilize the wooden end where the forged steel was inset into the wooden handle, and the steel point with a cutter/gouge and separate “bent-over sharp lip”/gouge Dimensions: Length 7.25 inches; Height 2 inches; Width 1 inch. Object ID: 2017.0.34.625

This tool has a wooden handle, a brass band that helped stabilize the wooden end where the forged steel was inset into the wooden handle, and the steel point with a cutter/gouge and separate “bent-over sharp lip”/gouge Dimensions: Length 7.25 inches; Height 2 inches; Width 1 inch. Object ID: 2017.0.34.625

Simply stated, a timber scribe included the components of the race knife. Lumbermen, shipbuilders, house wrights and carpenters, coopers, and surveyors, all used the timber scribe to make uniform marks on wood, but they could also use the elongated cutter/gouge to make free-hand marks. They used the race knife to make free-hand marks.

Appearances mattered. The timber scribe at The Henry Ford combines three natural materials – iron/steel, brass, and wood – all processed and refined in ways that make the tool pleasing to the eye, and useful to the woodsman or craftsman. The maker chamfered the edges of the wooden handle and scribed the brass collar.

An 1897 catalog from a Detroit hardware distributor, the Charles A. Strelinger Company, advertised a “rase knife or timber scribe.” The company sold three variations: a large size (though the catalog provided no dimensions), a small size, and a pocket rase knife. The large timber scribe included all three steel components (point with cutter gouge and “bent-over sharp lip” gouge) while the small version included just two of the three (point and gouge). The pocket rase knife likely consisted of just the gouge, which folded into the wooden handle of the knife, as seen below.

Rase Knife or Timber Scribe. Detail from Wood Workers’ Tools: Being a Catalogue of Tools, Supplies, Machinery, and Similar Goods used by Carpenters, Builders, Cabinet Makers, Pattern Makers, Millwrights, Carvers, Ship Carpenters, Inventors, Draughtsmen, and [also] all “Wood Butchers” not included in Foregoing Classification and in Manufactories, Mills, Mines, etc., etc. Detroit Michigan: Charles A. Strelinger & Company, 1897, page 662. In the collection of the Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford, Dearborn, Michigan.

The tool in The Henry Ford's collection compares to the large timber scribe illustrated in Strelinger & Company’s 1897 catalog. The tool’s dimensions (7.25 inches long) inform us about the size of a “large” scribe.

Charles A. Strelinger was born in Detroit in 1856. The 1897 catalog Charles A. Strelinger Company indicated that the company had 30 years of experience in manufacturing and selling tools, supplies and machinery. Strelinger’s approach to advertising his wares through print media indicated how little change occurred in the tool business. The front page of the catalog had a blank space to write in the date, and, as he explained in “This Year’s Catalogue”: “our 1895 catalogue is also our 1896-’97-’98, and perhaps, 1899 catalogue. If we were selling Seeds and Plants, Ladies’ Hats and Bonnets, Patent Medicines, etc., we would, doubtless, find it necessary to issue a new catalogue every year, but our goods are of a stable nature, changes are comparatively few, and we are not warranted to going to the expense of printing a new book every year.”

The timber scribe and the Strelinger Company catalog confirm the need for specialized tools that serve many in various wood-working trades. The Company was resourceful in advertising, because the hand tools in woodworking were remarkably standardized by the late-nineteenth century and remained useful despite industrialization.

Debra A. Reid is Curator, Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford received funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) in 2017 to support a three-year project to conserve, rehouse, and digitize thousands of objects. This is work, supported through IMLS’s Museums for America Collections Stewardship project, will continue over three years as The Henry Ford consolidates offsite collections into a new location on campus. The work “will improve the physical condition of the project artifacts through conservation treatment, rehousing, and removal to improved environments.” Finally, IMLS funding “will facilitate collections access through the creation of catalog records and digital images, available to all via THF's Digital Collections.”

A series of blogs shares the stories of small items that tell big stories of innovation, ingenuity, and resourcefulness, and that relate to other collections and interpretation at The Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford & the STEMIE Coalition: Joining Forces

I’m pleased to announce that The Henry Ford and the STEMIE Coalition have officially joined forces to strengthen our invention education offerings across the country and around the world. Several members of the STEMIE Coalition are now part of The Henry Ford organization.

I’m pleased to announce that The Henry Ford and the STEMIE Coalition have officially joined forces to strengthen our invention education offerings across the country and around the world. Several members of the STEMIE Coalition are now part of The Henry Ford organization.

For those of you who don’t know, The STEMIE Coalition is a non-profit, umbrella membership organization of youth invention and entrepreneurship programs across the U.S. and globally and is best known for producing NICEE, the National Invention Convention and Entrepreneurship Expo.

We held the 2018 NICEE for the very first time here in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation this past June, and now we will be the permanent home of that program during which more than 400 students from 20 states and two countries qualified to attend.

In fact, when we started the conversations around the planning and hosting of NICEE here at The Henry Ford, it was then that we realized how similar our missions are, that both organizations shared a vision of creating the next generation of innovators, inventors and entrepreneurs and it was apparent to us that combined, we could reach significantly more students and make a greater impact.

I see this as a marriage of missions. The STEMIE Coalition’s mission to train every child in every school in invention and entrepreneurship skills aligns with The Henry Ford’s quest to move our country forward through innovation and invention. This expands the pipeline of products available to address kids preK-12 and to increase the accessibility of invention education for students of all backgrounds. This is an investment in unleashing the next generation of innovators and entrepreneurs and creating tomorrow’s workforce.

Thank you, as always, for helping The Henry Ford activate our mission and for your continued support. See you soon.

Patricia E. Mooradian is President & CEO of The Henry Ford.

education, childhood, Invention Convention Worldwide, entrepreneurship, innovation learning, by Patricia E. Mooradian

Black Entrepreneurs during the Jim Crow Era

Two Sisters Beauty Salon, 1945-50. THF240367

“Jim Crow” laws—first enacted in the 1880s by angry and resentful Southern whites against freed African Americans—separated blacks from whites in all aspects of daily life. Favoring whites and repressing blacks, these became an institutionalized form of inequality.

Jim Crow was a character first created for a minstrel-show act during the 1830s. The act—featuring a white actor wearing black makeup—was meant to demean and make fun of African Americans. Applied to the later set of laws and practices, the name had much the same effect. THF98689

In the Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states had the legal power to require segregation between blacks and whites. Jim Crow laws spread across the South virtually anywhere that the two races might come in contact. In the North and Midwest, segregation became equally entrenched through informal customs and practices. Many of these laws and practices lasted into the 1960s, until outlawed by the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Through separate (and inferior) public facilities like building entrances, elevators, cashier windows, and drinking fountains, African Americans were reminded everywhere of their second-class status. THF13419, THF13421

It took a great deal of courage, resilience, and strength of character for African Americans to maintain their self-respect and battle the daily humiliation of Jim Crow. The black church, self-help organizations, and men’s and women’s clubs offered refuge, support, and protection, while the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) provided potential legal assistance.

The NAACP, formed in 1909, emphasized fighting for racial equality through legal action rather than political protest or economic agitation. THF11647

Out of the demeaning environment of Jim Crow arose the opportunity for some African Americans to establish their own businesses. The more cut off that black communities became from white communities and the more that white businessmen refused to cater to black customers, the more possible it became for enterprising black entrepreneurs to create viable businesses of their own.

Most of these businesses were local, small-scale, and family-run. Many black entrepreneurs followed the tenets of Booker T. Washington, who had established the National Business League in 1900 to promote economic self-help. Washington advocated economic development as the best path to racial advancement and the means to eventually challenging the racial prejudice of Jim Crow. While Washington’s precepts would become increasingly out of step with the times, especially when the Civil Rights movement gained momentum, the support for his ideas among black entrepreneurs of the Jim Crow era is repeatedly evident in the naming of businesses after Washington.

The following images from the collections of The Henry Ford provide an intriguing window into the world of black enterprise and entrepreneurship during the Jim Crow era.

Barber Shops

Rodger Clark’s No. 1 Barber Shop, c. 1950. THF240383

Black barbers had long cut white customers’ hair as part of their traditional second-class status in service to white people. But, by the early 20th century, white patrons had begun to shift their business to white-owned shops. A new generation of black barbers proudly established shops within their own communities, catering to a growing black consumer market. They knew that their white counterparts would offer no competition, as they did not want the close contact with blacks that cutting hair demanded. Nor could white barbers offer black men the kind of haircut and shave that they themselves knew how to give.

The cost to enter the field was low but black barbers’ status was high. They generally attracted a regular customer base, akin to church preachers. Men congregated and felt comfortable in these shops, and conversation flowed freely, both about local goings-on and larger racial matters that concerned them all. Barber shops remained important spheres of influence during and after the Civil Rights era.

Beauty Parlors

The rise of black female beauty culture paralleled larger trends in society, especially the influence of mass media like movies and popular magazines. Several black female entrepreneurs spearheaded an emerging beauty culture industry—the most famous of these being Madam C. J. Walker. Some enterprising black women, initially trained as agents to sell special hair preparation and cosmetic products (so-called “beauty systems”), eventually opened their own beauty shops as permanent spaces to facilitate their work as “beauty culturists.” With the little capital needed to start their own businesses, they could free themselves from economic dependence on their husbands or on white employers. It was respectable work, considered doing their part for racial progress and the economic uplift of the black race.

Beauty parlors became places where black women could indulge in moments of pampering, self-indulgence, and relaxation while also letting off steam, gossiping, and speaking their minds. Increasingly, beauty parlors became vital public spaces that nurtured debate and activism among women within black communities.

Undertakers and Funeral Directors

Booker T. Washington was depicted on the front of this cardboard handheld fan for the Jacob Brothers Funeral Home, Indianapolis, Indiana, circa 1955. As advertised on the back, the funeral home promised air-conditioning and an organ in its chapels. THF224305

By the 1920s, funeral homes had emerged across the country as primary locations for carrying out the responsibilities of handling and burying the deceased. These first emerged in large towns and cities and gradually spread to rural regions. Funeral homes became a particularly lucrative avenue of entrepreneurship for blacks, which lacked white competition because of the close physical contact that was involved in this work. When African Americans were excluded from joining the National Funeral Directors Association, they organized their own independent organization in 1925.

People entrusted black undertakers and funeral directors in their local communities with the proper and responsible treatment of their deceased loved ones. These entrepreneurs offered an appropriate mixture of respect for traditional religious practices, modern American values, and the changing desires of local neighborhoods. Some black funeral homes flourished through aggressive marketing and modern amenities like spacious limousines.

Cafés, Taverns, and Liquor Stores

Dixie Liquor Store, St. Louis, Missouri, 1940s. THF240367

Saratoga Café and Sportsman Lounge, Chicago, Illinois, 1940s. THF240377

During the Jim Crow era, segregation may have been the law in the South but it was just as apparent in northern and midwestern cities. Restaurants, cafés, taverns, and liquor stores thrived in black neighborhoods, established by local businessmen and geared to local customers. These two stores—in St. Louis, Missouri and Chicago, Illinois—seem to have been extremely popular gathering places for both men and women.

Roadside Amenities

The Negro Motorist Green Book, 1949. THF 77183

It was one thing to frequent the businesses in your own neighborhood. But what happened when you took an out-of-town road trip? Where might you and your family inadvertently encounter hostility, be turned away, perhaps even risk your lives? Black postal worker Victor H. Green attempted to help black travelers combat this dilemma by creating The Negro Motorist Green Book. From 1936 to 1966, the Green Book offered a directory of safe places for African-American travelers. This included not only the expected roadside amenities of lodgings, service stations, and restaurants, but also listings of many of the classic businesses found in local neighborhoods—like barber shops, beauty parlors, liquor stores, and nightclubs. [For more on the Green Book, see this blog post.

A. G. Gaston Motel, 1954. THF 104701, 104700

One of the most difficult and risky aspects of cross-country travel for African Americans was the question of where to stay overnight. The Negro Motorist Green Book attempted to update its listings as often as possible, while word of mouth helped African Americans learn of safe places—who often drove miles out of their way to get to them. But the fact remained that the most extensive listings of hotels and motels were in northern metropolises with large populations of black Americans. In smaller towns, a tourist home or two might be listed—which meant staying in a room in someone’s house. Many towns lacked even a single listing.

In 1954, a new kind of black-owned lodging opened in Birmingham, Alabama, coinciding with a black Baptist convention in town. Billed “The Nation’s Newest and Finest Motel,” it was built, owned, and run by pioneering black entrepreneur Arthur George (A. G.) Gaston. Gaston also established several other businesses in Birmingham, including a bank, radio stations, the Booker T. Washington Insurance Company, a funeral home, and a construction firm.

Modeled after the groundbreaking Holiday Inns that had recently opened in Memphis, Tennessee, the A. G. Gaston Motel included 32 rooms, each with their own air-conditioning and telephone. Gaston remarked that opening this motel “means that many persons passing through our city will have a fine place to stay.” In 1963, the Gaston Motel became the epicenter of Birmingham’s Civil Rights protests and demonstrations.

Berry Gordy and Motown Records

This Smokey Robinson and the Miracles 45 rpm record was licensed to and issued nationally by Chess Records because Motown as yet lacked a national distribution network. THF170558

Berry Gordy Jr., founder of Motown Records in Detroit, Michigan, in 1959, created a business that successfully bridged the Jim Crow era and the post-Civil Rights Act era. He accomplished this by accurately predicting the coming of an integrated market of consumers for black popular music.

In 1922, Gordy’s father, Berry Sr., moved his family to Detroit from Georgia—an area steeped in Jim Crow laws and practices—because he faced hostility and potential violence from local whites when his food distribution business proved too successful. Berry Sr. established the Booker T. Washington Grocery Store in the black working-class neighborhood of Detroit, which soon also became highly successful. All the while, he encouraged his children to be industrious and establish their own business ventures.

Inspired by the legendary boxer Joe Louis, Berry Jr. first dreamed of becoming a famous boxer but he eventually gravitated to his other interest—music. From record store owner to songwriter to multi-million-dollar record producer and distributor, Gordy used his business savvy to redefine black music coming out of Detroit as popular music that both blacks and whites would want to hear and buy. Throughout the monumental success of his career, Gordy claimed that he had continually upheld his family’s business ethic and the self-help ideals of Booker T. Washington.

The Jim Crow Era provided the impetus for a number of black businesses to grow and flourish, instilling a sense of pride within black communities, serving as symbols of racial progress, and promising safe places to do business and socialize. The conversation and ideas that flowed freely in black business establishments also helped raise consciousness and establish a sense of solidarity within black neighborhoods. When the Civil Rights movement gained momentum—offering an end to the indignities and disenfranchisement of Jim Crow—many black entrepreneurs did what they could to support the movement. After the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964, and segregation was declared illegal, black entrepreneurs could take pride in the role they had played in the Civil Rights movement despite the fact that the future viability of their segregated businesses were now in jeopardy.

To read more on these topics, check out these helpful books:

- Cutting Across the Color Line: Black Barbers and Barber Shops in America, by Quincy T. Mills (2013)

- Style and Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women, 1920-75, by Susannah Walker (2007)

- Pageants, Parlors, and Pretty Women: Race and Beauty in the 20th Century South,(2016)

- Dancing in the Street: Motown and the Cultural Politics of Detroit, by Suzanne E. Smith (1999)

Donna R. Braden is the Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 19th century, entrepreneurship, by Donna R. Braden, African American history

Motown’s Contribution to the Civil Rights Movement

Motown Record Album, “The Great March to Freedom: Rev. Martin Luther King Speaks, June 23, 1963.” THF31935

Detroit’s Walk to Freedom, held on June 23, 1963, helped move the southern Civil Rights struggle to a new focus on the urban North. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. later called this march “one of the most wonderful things that has happened in America.”

Organized by the Detroit Council on Human Rights, this was the largest Civil Rights demonstration to date. Its main purpose was to speak out against Southern segregation and the brutality that faced Civil Rights activists there. It was also meant to raise consciousness about the unique concerns of African Americans in the urban North, which included discriminatory hiring practices, wages, education, and housing. The date was chosen to correlate with both the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and the 20th anniversary of the 1943 Detroit race riots that had left 34 people (mostly African American) dead. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who agreed to lead the march, had by this time become committed to uniting both North and South through his grand vision of achieving racial justice by using non-violent protest.

On the day of the march, about 125,000 people filed down Woodward Avenue, singing freedom songs and carrying signs demanding racial equality. Some 15,000 spectators watched them pass by a 21-block area before turning west down Jefferson Avenue to Cobo Hall. Cobo was filled to capacity to hear the speeches of the march’s leaders while thousands more listened to them on loudspeakers outside. Of the speeches given that day, Dr. King’s was the most memorable. People were riveted while he expressed his vision for the future, sharing a dream that foreshadowed the “I Have a Dream” speech that he would give a few months later at the March on Washington.

Berry Gordy, founder of the Motown Record Corporation, considered Detroit’s Walk to Freedom to be such a historic event that he offered the resources of his Hitsville studio to produce a record album documenting Dr. King’s impassioned words. Gordy heightened the drama of the event by titling the album, “The Great March to Freedom: Reverend Martin Luther King Speaks.” He believed that this record belonged in every home, that it should be required listening for “every child, white or black.” No one realized at the time, including Gordy, that the August March on Washington would become the more remembered event.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dreams of social justice, voiced at Detroit’s Walk to Freedom, would prove elusive. Despite the fact that Detroit had gained a national reputation for being a “model city” of race relations at the time, in reality the city’s African-American population faced unemployment, housing discrimination, de facto segregation in public schools, and police brutality. Ultimately this disconnect between perception and reality would lead to the violence and civil unrest of July 1967.

For more on the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom held on August 28, 1963, take a look at this post.

Donna R. Braden is the Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

1960s, 20th century, music, Michigan, entrepreneurship, Detroit, Civil Rights, by Donna R. Braden, African American history

The Tucker 48: “The Car You Have Been Waiting For”

The 1948 Tucker

The Tucker '48 automobile, brainchild of Preston Thomas Tucker and designed by renowned stylist Alex Tremulis, represents one of the most colorful attempts by an independent car maker to break into the high-volume car business. Ultimately, the Big Three would continue to dominate for the next forty years. Preston Tucker was one of the most recognized figures of the late 1940s, as controversial and enigmatic as his namesake automobile. His car was hailed as "the first completely new car in fifty years." Indeed, the advertising promised that it was "the car you have been waiting for." Yet many less complimentary critics saw the car as a fraud and a pipe dream. The Tucker's many innovations were and continue to be surrounded by controversy. Failing before it had a chance to succeed, it died amid bad press and financial scandal after only 51 units were assembled.

Much of the appeal of the Tucker automobile was the man behind it. Six feet tall and always well-dressed, Preston Tucker had an almost manic enthusiasm for the automobile. Born September 21, 1903, in Capac, Michigan, Preston Thomas Tucker spent his childhood around mechanics' garages and used car lots. He worked as an office boy at Cadillac, a policeman in Lincoln Park, and even worked for a time at Ford Motor Company. After attending Cass Technical School in Detroit, Tucker turned to salesmanship, first for Studebaker, then Stutz, Chrysler, and finally as regional manager for Pierce-Arrow.

As a salesman, Tucker crossed paths at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway with the great engine designer Harry A. Miller, and in 1935 they formed Miller-Tucker, Inc. Their first contract was to build race cars for Henry Ford. The company delivered ten Miller-Ford Indy race cars, but they proved inadequate for Ford and he pulled out of the project.

During World War II, automobile companies' operations were dedicated to the war effort. Denied new car models for four years, by the war's end Americans were eager for a new automobile, any new automobile. The time was right for Tucker to begin his dream. In 1946, he formed Tucker Corporation for the manufacture of automobiles.

Tucker Corporation employee badge. THF135737

He set his sights on the old Dodge plant in the Chicago suburb of Cicero, Illinois. Spanning over 475 acres, the plant built B-29 engines during World War II, and its main building, covering 93 acres, was at the time the world's largest under one roof. The War Assets Administration (WAA) leased Tucker the plant provided he could have $15 million dollars capital by March 1 of the following year. In July, Tucker moved in and used any available space to build his prototype while the WAA inventoried the plant and its equipment.

The fledgling company needed immediate money, and Tucker soon discovered that support from businessmen who could underwrite such a venture meant sacrificing some, if not all, control of his company. To Tucker, this was not an option, so he conceived of a clever alternative. He began selling dealer franchises and soon raised $6 million dollars to be held in escrow until his car was delivered. The franchises attracted the attention of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and in September of 1946 it began an investigation, the first of a series that would last for the next three years.

The agreements were rewritten to SEC satisfaction and the franchise sales proceeded. In October, Tucker began another proposal: a $20 million stock issue contingent upon a completed prototype and clearance by the SEC. That same month, Tucker met his first serious obstacle. Wilson Wyatt, head of the National Housing Agency, ordered the WAA to cancel Tucker's lease and turn the plant over to the Lustron Corporation to build prefabricated houses.

Tucker may have been an unfortunate pawn in a bureaucratic war between the housing agency and the WAA, but the battle continued until January of 1947. Franchise sales fell, stock issues were delayed, and Tucker's reputation was severely damaged. In the end, he kept his plant, but the episode made him some real enemies in Washington, including Michigan Senator Homer Ferguson. But Tucker did find some allies. The WAA extended Tucker's $15 million cash deadline to July 1 and Senator George Malone of Nevada began his own investigation of the SEC.

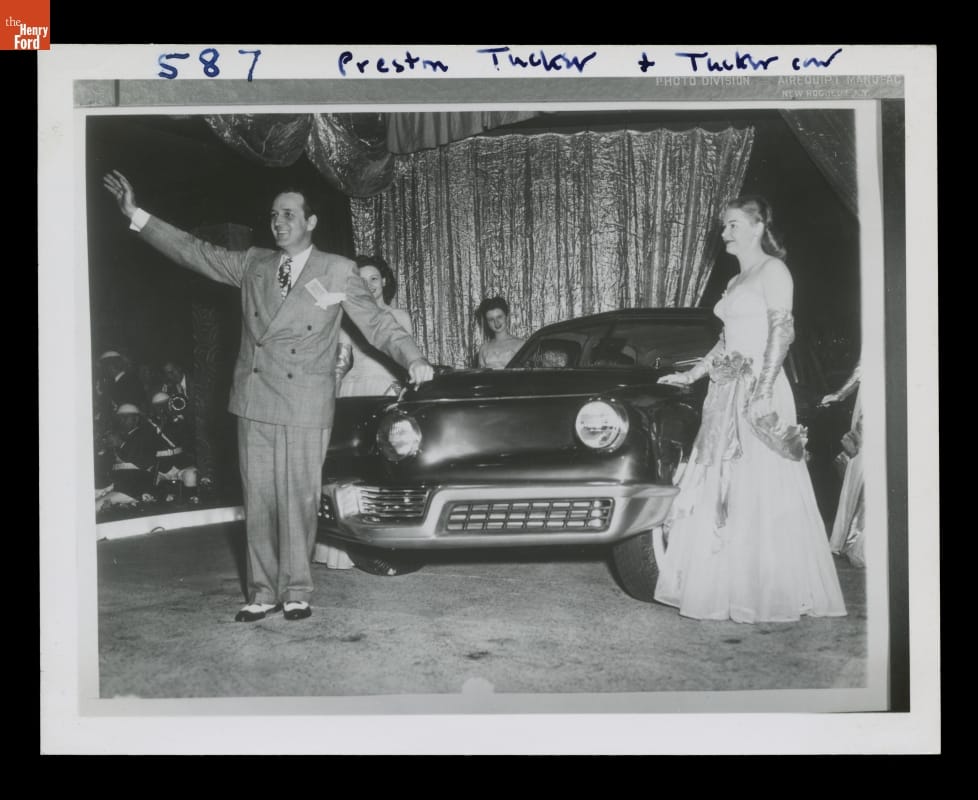

Meanwhile, Tucker still had a prototype to build. During Christmas 1946, he commissioned Alex Tremulis to design his car and ordered the prototype ready in 100 days. The time frame was unheard of, but necessary. Unable to obtain clay for a mock-up, engineers – many from the race car industry – began beating out sheet iron, a ridiculous way to build a car but a phenomenal achievement. The first car, completely hand-made, was affectionately dubbed the "Tin Goose." Preston Tucker unveils his car, June 19, 1947. THF135047

Preston Tucker unveils his car, June 19, 1947. THF135047

The Tucker '48 premiered June 19, 1947, in the Tucker plant before the press, dealers, distributors and brokers. Tucker later discarded many of the Tin Goose's features, such as 24-volt electrical system starters to turn over the massive 589-cubic-inch engine. For the premier, workers substituted two 12-volt truck batteries weighing over 150 pounds that caused the Tucker's suspension arms to snap. Speeches dragged on as workers behind the curtain tried feverishly to get the Tin Goose up and running. Finally, before the crowd of 5000, the curtains parted and the Tucker automobile rolled down the ramp from the stage and to its viewing area where it remained for the rest of the evening. Stock finally cleared for sale on July 15.

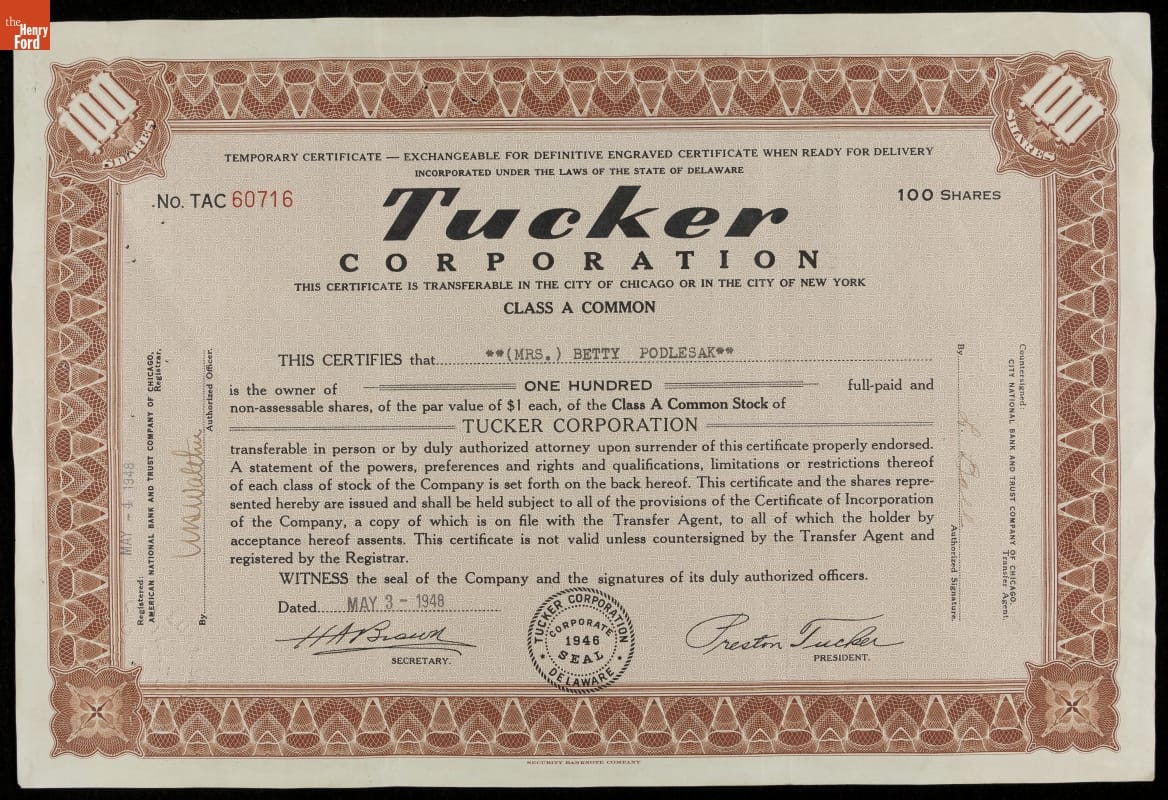

By the spring of 1948, Tucker had a pilot production line set up but his stock issue had been $5 million short and he again needed immediate money. He began a pre-purchase plan for Tucker automobile accessories such as radios and seat covers. Although he raised $1 million, advanced payment on accessories to a car not yet in production was the final straw for the SEC. On May 28, 1948, the SEC and the Justice Department launched a full-scale investigation. Investigators swarmed the plant and Tucker was forced to stop production and lay off 1,600 workers. Receivership and bankruptcy suits piled up, creditors bolted, and stock plunged. A Tucker stock certificate for 100 shares, dated May 3, 1948. THF208633

A Tucker stock certificate for 100 shares, dated May 3, 1948. THF208633

The SEC's case had to show that the Tucker car could not be built, or – if built – would not perform as advertised. But Tucker was building cars. Seven Tuckers performed beautifully at speed trials in Indianapolis that November, consistently making 90 mph lap speed. However, after Thanksgiving, a skeletal crew of workers assembled the last cars that the company would ever produce. In January 1949, the plant closed and the company was put under trusteeship.

"Gigantic Tucker Fraud Charged in SEC Report" ran the Detroit News headline in March. The article related an SEC report recommending conspiracy and fraud charges against Preston Tucker. Incensed, Tucker demanded to know how the newspaper had seen the report even before him. SEC Commissioner John McDonald later admitted he delivered the report to the paper in direct violation of the law. Feeling tried and convicted by the press, Tucker wrote an open letter to many newspapers around the country.

On June 10, Tucker and seven of his associates faced a Grand Jury indictment on 31 counts – 25 for mail fraud, 5 for SEC regulation violation, and one on conspiracy to defraud. The trial opened on October 5, 1949, and from the beginning the prosecution based its entire case on the "Tin Goose" prototype. It refused to recognize the 50 production cars and called witness after witness who, under cross-examination, ended up hurting the government's case. In the end, Tucker's defense team merely stated that the government had failed to prove any offense so there was nothing to defend.

On January 22, 1950, the jury found the defendants innocent of any attempt to defraud, but the verdict was a small triumph. The company was already lost. The remaining assets, including the Tucker automobiles, were sold for 18 cents on the dollar. Seeking some recompense, Preston Tucker filed a series of civil suits against news organizations that he believed had defamed him in the months leading up to his trial. His targets included the Detroit News, which he hit with a $3 million libel suit in March 1950.

In preparation for its defense, the Evening News Association – publisher of the Detroit News – acquired Tucker serial number 1016 for examination. But the suit never reached the courtroom. Preston Tucker was diagnosed with lung cancer and died December 26, 1956. The Evening News Association subsequently presented car 1016 to The Henry Ford, where it remains today.

Illinois, Michigan, 20th century, 1940s, manufacturing, entrepreneurship, cars

Mrs. Cohen: A Fashion Entrepreneur

Life is often a juggling act of work, play and family. While current-day clothiers experience the trials and tribulations of being small-town entrepreneurs in the big business of fashion, more than 100 years ago many women were facing similar circumstances, leaning on their sense of style to furnish a living.

In the late 1800s, Elizabeth Cohen had run a millinery store next to her husband’s dry goods store in Detroit. When he died and left her alone with a young family, she consolidated the shops under one roof. Living above the store, she was able to run a business and earn a living while staying near her children.

Cohen leveraged middle-class consumers’ growing fascination with fashion, using mass-produced components to create hats in the latest styles and to the individual tastes of customers. To attract business, resourceful store owners like Mrs. Cohen displayed goods in storefront windows and might have advertised through trade cards or by placing advertisements in newspapers, magazines or city directories.

“While Mrs. Cohen was more likely following fashion than creating it, it did take creativity and design skill,” Jeanine Head Miller, curator of domestic life at The Henry Ford, said of Cohen’s millinery prowess. “She was a small maker connecting with local customers in her community — a 19th-century version of Etsy, perhaps, but without the online reach.”

And she certainly gained independence and the satisfaction of supporting her family while selling the hats she created from the factory-produced components she acquired. “People can appreciate the widowed Elizabeth Cohen’s balancing act,” added Miller, “successfully caring for her children while earning a living during an era when fewer opportunities were available to women.”

Jennifer LaForce is a writer for The Henry Ford Magazine. This story originally appeared in the June-December 2016 issue.

19th century, women's history, The Henry Ford Magazine, shopping, Michigan, making, hats, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, fashion, entrepreneurship, Detroit, design, Cohen Millinery, by Jennifer LaForce

Victor H. Green and “The Negro Motorist Green Book”

Green Book 1949 front cover. THF77183

“Where Will You Stay Tonight?”

Freedom. Independence. Hitting the open road without a care in the world. After years of being tied down to railroad schedules, motorists in the early 20th century used words like these to describe the joys of cross-country travel by automobile.

African Americans were as eager to purchase automobiles as anyone, to escape the indignities of “Jim Crow” laws that dictated segregated waiting rooms and railroad cars in the South, and to avoid more subtle—yet equally humiliating—forms of discrimination elsewhere. But the joys of motoring without care did not apply to them.

Sign from segregated railroad station, 1921. THF93445

For, once they stopped along the road—anywhere along the road in virtually any part of the country—segregation, discrimination, and humiliation returned in force. It was at hotels and tourist cabins that denied them lodging for the night; at restaurants, where they were turned away for meals or a cup of coffee; and at service stations, where requests to fill up with gasoline, repair a vehicle, or use the restroom were denied. According to Civil Rights leader Julian Bond, “It didn’t matter where you went—Jim Crow was everywhere.” Constantly alert to situations that might be humiliating, African-American motorists took to packing food, blankets, pillows, portable containers with gasoline, and old coffee cans or buckets to use as toilets. They made prior plans to stop overnight with relatives or friends, sometimes driving miles out of their way.

Even worse than segregation laws and customs, Black travelers had to constantly navigate a minefield of uncertainty and risk on the road. Would this place be safe to stop? Could my children use the bathroom here? African-American motorists faced the potential of physical violence, racial profiling by police (targeting individuals for crimes based upon their race), or forcible expulsion from whites-only “sundown towns” in both the North and South, with their laws insisting that non-whites leave city limits by dusk or face the consequences. Some African-American travelers did not make it to their destinations, they just disappeared. It is no wonder that the question, “Where Will You Stay Tonight?” was always top of mind.

Victor Green Addresses a Need

“The Negro Motorist Green Book” was the brainchild of Victor H. Green, a black postal carrier in Hackensack, New Jersey, who later moved to Harlem in New York City. As Green tells it, the idea for this guidebook came to him in 1932, when he decided to do something about his own frustrating travel experiences as well as the constant complaints he heard from friends and neighbors about difficult and painfully embarrassing experiences they had while traveling by automobile. Green modeled the guide after those created for Jewish travelers, a group that had long experienced discrimination at vacation spots. The first edition of The Green Book, produced in 1936, was limited to listings in New York City. But the demand for the guide was so great that, by the following year, it became national in both scope and distribution.

Green Book 1937 ed. THF99195

Although often including longer editorial features, at its heart The Green Book was a directory of safe places for African-American travelers, including hotels, motels, tourist homes (the homes of private individuals who were willing to offer a room for the night), restaurants, beauty and barber shops, service stations, garages, road houses, taverns, and nightclubs. The most prolific listings were in metropolises with large populations of black Americans, like New York, Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Perhaps more valuable to travelers were the listings in smaller towns far removed from these cities.

The Los Angeles listings in the 1949 Green Book were quite extensive compared to other California towns and cities.THF77190

Green collected the listings through his contacts in the postal workers’ union, as well as by asking Green Book users to submit suggestions. As the book became more popular, Green commissioned agents to solicit new business listings as well as to verify the accuracy of existing ones.

From his small-scale publishing house in Harlem, Green distributed the books by mail order, to black-owned businesses, and at Esso (Standard Oil) service stations—a rare gasoline distributor that franchised to African Americans. He sold copies at black churches, the Negro Urban League, virtually anywhere that African Americans were bound to encounter them.

The Michigan listings in the 1949 Green Book were most extensive in Detroit and the black resort of Idlewild. THF77203

Rise and Decline

Publication of The Green Book was suspended between 1942 and 1946, because of World War II, but it started up again in earnest with the postwar travel boom in 1947. Ever the entrepreneur looking for ways to aid African American travelers, Green branched out that year to create a Vacation Reservation Service, a travel agency that booked reservations at any hotel or resort listed in the book. That same year, he also issued a supplementary directory of summer resorts that welcomed black vacationers, called the Green Book Vacation Guide.

Left: An ad for The Green Book Vacation Guide in the 1949 Green Book. THF 77185

In 1952, Green retired from the postal service and became a full-time publisher. He renamed the guidebook “The Negro Travelers’ Green Book” to reflect the increasing popularity of international travel by ship and airplane. By 1955, the book was endorsed and in use by the American Automobile Association and its hundreds of affiliated clubs throughout the country, as well as travel bureaus, bus lines, airlines, travelers’ aid societies, libraries, and thousands of subscribers.

The market for The Green Book began eroding in the 1960s, especially after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that legally prohibited racial segregation. Increasing numbers of middle-class African Americans began to question whether the book was actually doing more harm than good because it continued to encourage Jim Crow practices by steering black travelers to segregated businesses rather than encouraging integration. New, interstate-highway hotels, which were integrated, became preferable to detouring to black-owned lodgings in remote locations. The Green Book continued until 1966, published by Victor Green’s family after his death in 1960. Until the last year of publication, the book maintained that listing black-friendly businesses guaranteed hassle-free vacations for African-American families.

For 30 years, The Green Book protected African Americans from difficulties, indignities, and humiliation during their travels. Green charged only enough to make a modest profit. He never became rich; it was really all about helping out. In publishing this book, Green not only helped thousands of African Americans take more enjoyable vacations but also gave a tremendous boost to black-owned businesses across the country during the challenging Jim Crow era.

Peruse the entire 1949 “Negro Motorist Green Book” in our digital collections.

Continue Reading1950s, 1930s, 1940s, 20th century, travel, roads and road trips, entrepreneurship, cars, by Donna R. Braden, African American history