Posts Tagged ford rouge factory complex

Ford’s Game-Changing V-8 Engine

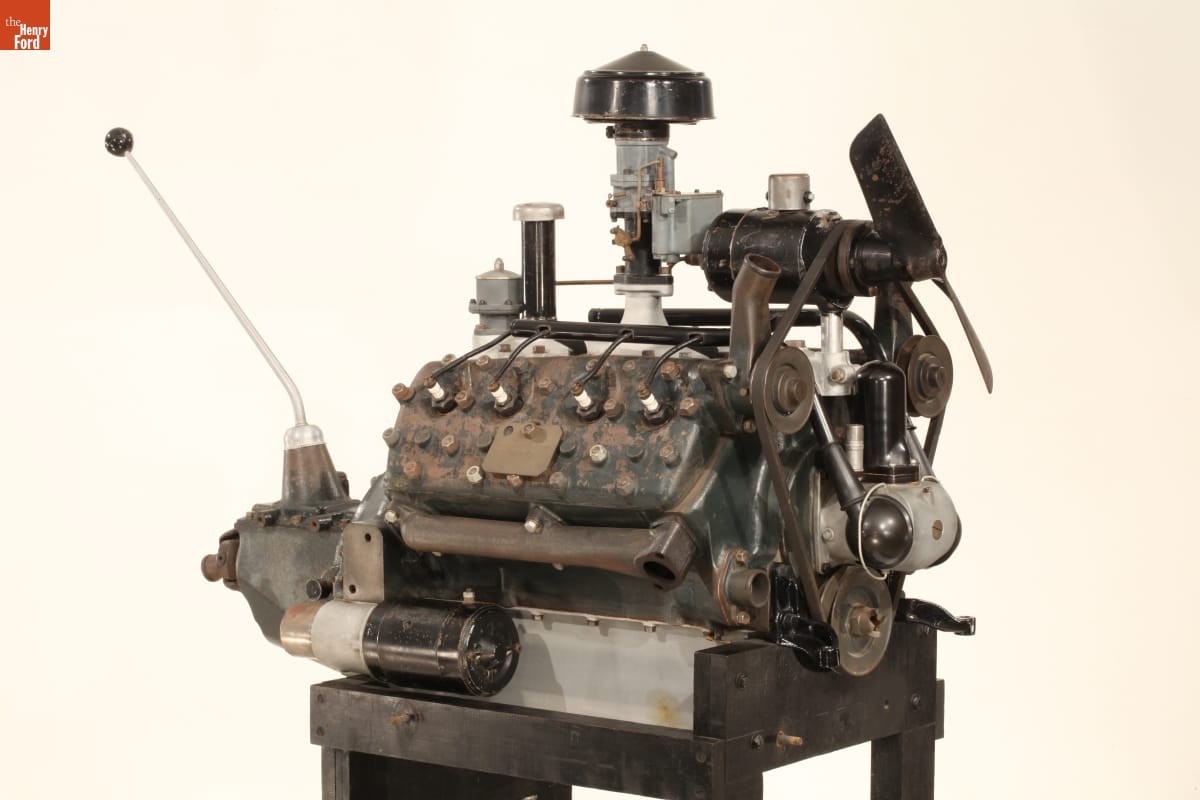

1932 Ford V-8 Engine, No. 1. / THF101039

It’s been said that when the Ford flathead V-8 went into production in 1932, Ford Motor Company revolutionized the automobile industry—again. And the engine put the hot rod movement into high gear.

What made this engine revolutionary? It was the first V-8 light enough and cheap enough to go into a mass-produced vehicle. The block was cast in one piece, and the design was conducive to backyard mechanics’ and gearheads’ modifications.

This 1932 brochure illustrates the difference between the Ford V-8, with the cylinders and crankcase cast as a single block of iron, and a traditional V-8, built by bolting separate cylinders onto the crankcase. / THF125666

With so much at stake, you would think Henry Ford would set up his engineers tasked with the engine’s design in the most state-of-the-art facility he had at his disposal.

Not so. Instead, Ford sent a handpicked crew to Greenfield Village to gather in Thomas Edison’s Fort Myers Laboratory, which had been moved from Fort Myers, Florida, to Dearborn not long before.

Henry Ford and Thomas Edison with Fort Myers Laboratory at its original site, Fort Myers, Florida, circa 1925. / adapted from THF115782

“Henry Ford likely used the building because it provided his engineers with privacy and freedom from distraction,” said Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. “I imagine he also thought the team might be inspired by the surroundings.”

Ford’s plan worked. In just two years, Ford’s engineering crew left the lab in Greenfield Village with a final design.

Continue Reading

Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Henry Ford, Ford Motor Company, manufacturing, design, engineering, engines, race cars, cars, racing, The Henry Ford Magazine

Work, Play, and Leadership at Ford’s Dearborn Truck Plant

Corey Williams, Dearborn Truck Plant Manager, will tell you that the culture at the plant where the F-150 is built is one of a kind. / Photo by Nick Hagen

Corey Williams, Dearborn Truck Plant Manager, will tell you that the culture at the plant where the F-150 is built is one of a kind. / Photo by Nick Hagen

Corey Williams has been a part of the Dearborn Truck Plant management team for nearly four years, promoted to plant manager in January 2021, and he’s worked at many Ford facilities in a variety of management positions over the 25-plus years he’s been with Ford. He’ll tell you with conviction that the Dearborn Truck Plant, where the Ford F-150 is built and The Henry Ford’s Ford Rouge Factory Tour welcomes thousands of visitors a year, is unlike anywhere else in the world.

“Every Ford plant has the same goals, metrics and objectives—we all want to deliver the best, highest-quality product to the customer that we can,” said Williams. “But at Dearborn Truck, the culture is different. And when I say different, I mean everyone here understands that we are building America’s bestselling truck and the sense of pride in that is like no other.”

“Everybody knows that we are leaders, never followers,” he added. “That if it can be done, it will be done at DTP [Dearborn Truck Plant]—at not only the highest rate and volumes but with the greatest efficiency.”

Ford F-150 Truck Assembly at the Dearborn Truck Plant at the Ford Rouge Complex

That attitude and mental mantra fit perfectly with Williams’ persona. He’s not afraid to admit he’s an ultracompetitive guy who feeds off having to face the next challenge.

“I’ve been a sports guy my entire life,” he said. “I love to compete and like the idea of a team—the collaborative part of it and how you have to work together toward a common goal.”

And when asked about the new set of players—vehicles as well as workers—that are now ready to call the Ford Rouge Complex home along with Dearborn Truck Plant, Williams couldn’t be more excited. In 2022, the new Rouge Electric Vehicle Center is slated to open, employing hundreds of new hires and manufacturing the all-new battery-electric F-150. “Not a day goes by that people don’t ask me about our new hybrid, the EV center, and electric truck—the buzz and amazement just grows,” said Williams. “It’s a huge step in continuing our truck leadership and dominance. We are changing the game.”

Play to Work

Staff from Ford Motor Company and The Henry Ford trace some of their interest in STEM and manufacturing to childhood television, toys, and games, like this 1960s Clue set in our collection. / THF188744

We asked Corey and other members of Ford Motor Company’s vehicle launch team and The Henry Ford’s Ford Rouge Factory Tour what games, TV shows, toys, etc., they remember growing up that helped spark their interest in STEM and manufacturing.

Corey Williams, Plant Manager at Ford: Playing team sports in his younger years is a key precursor to his manufacturing management skills today. “Involving yourself in team events where you need to collaborate and compete as a team toward a common objective is extremely relevant from a STEM standpoint,” he said.

James Housel, Bodyshop Launch Manager at Ford: “Saturday morning cartoons watching ‘Wile E. Coyote, SUUUUUUPER Genius.’” The cartoon character is always obtaining crazy gizmos from fictional mail-order company Acme in the hopes of capturing the Road Runner.

Cynthia Jones, Director, Museum Experiences & Engagement, at The Henry Ford: “I loved to play the board games Risk and Clue. Both of those helped me identify patterns, test hypotheses, set strategy goals and learn from failure.” Like Williams, Jones, a dedicated swimmer through high school, credits competitive sports too.

Doug Plond, Senior Manager, Ford Rouge Factory Tour, at The Henry Ford: “As a really young tyke, I loved to build with my red cardboard brick set—knocking them down was the fun part. Once I got a bit older, I moved up to Lincoln Logs.”

Jennifer LaForce is Editorial Director at Octane and Editor of The Henry Ford Magazine. This post was adapted from an article first published in the June–December 2021 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

African American history, toys and games, The Henry Ford Magazine, sports, Michigan, manufacturing, Ford workers, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Ford Motor Company, Dearborn, childhood, cars, by Jennifer LaForce, alternative fuel vehicles

Back to School with the Henry Ford Trade School

As students everywhere settle into a new school year, let’s take a look back at the Henry Ford Trade School, founded in 1916.

The first six boys and three instructors, 1916. / THF626066

The school was formed to give young men aged 12–19 an education in industrial arts and trades. Boys who were orphans, family breadwinners, or from low-income families from the Detroit area were eligible for training and split their time between classroom and shop.

Henry Ford Trade School students and teachers in classroom, October 31, 1919. / THF284497

Students working on machinery at the Rouge Plant, 1935. / THF626060

The school started at the Highland Park plant, expanded to the neighboring St. Francis Orphans Home, and then to the Rouge plant and Camp Legion.

Henry Ford Trade School building, August 1, 1923. / THF284499

Trade School students on campus at the Rouge Plant, 1937. / THF626062

While students were receiving their education, they were also being paid an hourly wage, as well as a savings balance that was available to them at graduation. Students started off repairing tools and equipment, and as they gained more experience, moved on to working on machinery.

Student repairing goggles, Rouge Plant, 1938. / THF626064

Trade School student at the Ford Motor Company Rouge Plant, August 3, 1942. / THF245372

Students also got four weeks of vacation and daily hot lunches.

Students at lunch in the Rouge B Building cafeteria, 1937. / THF626068

The students were trained in a wide range of courses, both shop and academic, using textbooks created by the trade school. Shop courses ranged from welding to foundry work, and academic classes from English to metallurgy.

Shop Theory, 1942: cover and page 149. / THF626070, THF626075

When Ford Motor Company participated in various World’s Fairs, top trade school students were selected to demonstrate their unique style of learning.

Henry Ford Trade School demonstration, California Pacific International Exposition, San Diego, 1935. / THF209775

Students also had time for sports and clubs, including baseball, football, and radio club.

Henry Ford Trade School baseball team and manager, August 1927. / THF284507

Henry Ford Trade School football team, 1923. / THF118176

Claude Harvard with other Radio Club members, Henry Ford Trade School, March 1930. / THF272856

The Henry Ford Trade School closed in 1952. In its 36 years of operation, the school graduated over 8,000 boys from Detroit and the surrounding area. Students graduating from the trade school were offered jobs at Ford but were free to accept jobs elsewhere; among the graduates who later worked for Ford was engineer Claude Harvard (shown above). Other students went on to work in a wide range of endeavors from the automotive industry to arts and design, and even medicine and dentistry.

You can view more artifacts related to Henry Ford Trade School in our Digital Collections, or go more in-depth on our AskUs page. While the reading room at the Benson Ford Research Center remains closed at present for research, if you have any questions, please feel free to email us.

Kathy Makas is Reference Archivist at The Henry Ford. This post is based on a September 2021 presentation of History Outside the Box as a story on The Henry Ford’s Instagram channel.

school, childhood, Michigan, 20th century, sports, making, History Outside the Box, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, education, by Kathy Makas, books, archives

Henry Ford: Case Study of an Innovator

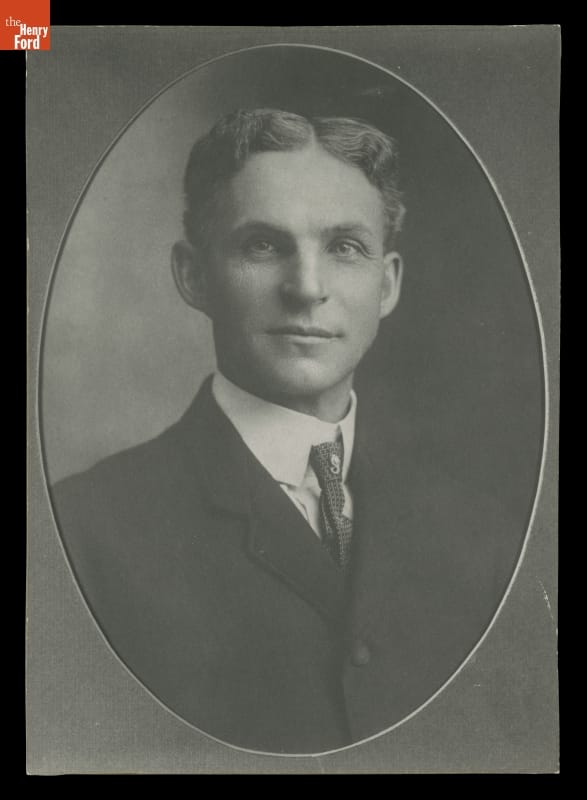

Henry Ford’s first official Ford Motor Company portrait, 1904. / THF97952

Henry Ford did not invent the automobile. But more than any other single individual, he was responsible for transforming the automobile from an invention of unknown utility into an innovation that profoundly shaped the 20th century and continues to affect the 21st. His work at Ford Motor Company revolutionized the automotive industry, setting new standards for production and accessibility.

Innovators change things. They take new ideas—sometimes their own, sometimes other people’s—and develop and promote those ideas until they become an accepted part of daily life. Innovation requires self-confidence, a taste for taking risks, leadership ability, and a vision of what the future should be. Henry Ford had all these characteristics, but it took him many years to develop all of them fully.

Portrait of the Innovator as a Young Man

Ford’s beginnings were perfectly ordinary. He was born on his father’s farm in what is now Dearborn, Michigan, on July 30, 1863. At this time, most Americans were born on farms, and most looked forward to being farmers themselves. Early on, Ford demonstrated some of the characteristics that would make him successful. In his family, he became infamous for taking apart his siblings’ toys as well as his own. He organized other boys to build rudimentary waterwheels and steam engines. He learned about full-size steam engines by becoming acquainted with the engines’ operators and pestering them with questions. He taught himself to fix watches and used the watches themselves as textbooks to learn the basics of machine design. Thus, at an early age, Ford demonstrated curiosity, self-confidence, mechanical ability, the capacity for leadership, and a preference for learning by trial and error. These characteristics would become the foundation of his whole career.

Artist Irving Bacon depicted Henry Ford in his first workshop, along with friends, in this 1938 painting. / THF152920

Ford could simply have followed in his father’s footsteps and become a farmer. But young Henry was fascinated by machines and was willing to take risks to pursue that fascination. In 1879, he left the farm to become an apprentice at a machine shop in Detroit. Over the next few years, he held jobs at several places, sometimes moving when he thought he could learn more somewhere else. He returned home in 1882 but did little farming. Instead, he operated and serviced portable steam engines used by farmers, occasionally worked in factories in Detroit, and cut and sold timber from 40 acres of his father’s land.

By now, Ford was demonstrating another characteristic—a preference for working on his own rather than for somebody else. In 1888, Ford married Clara Bryant, and in 1891 they moved to Detroit. Ford had taken a job as night engineer for the Edison Electric Illuminating Company—another risk on his part, because he did not know a great deal about electricity at this point. He took the job in part as an opportunity to learn.

Henry Ford (third from left, in white coat) with other employees at Edison Illuminating Company Plant, November 1895. / THF244633

Early Automotive Experiments: Failure and Then Success

Henry was a skilled student, and by 1896 had risen to chief engineer of the Illuminating Company. But he had other interests. He became one of the scores of other people working in barns and small shops trying to make horseless carriages. Ford read about these other efforts in magazines, copying some of the ideas and adding some of his own, and convinced a small group of friends and colleagues to help him. This resulted in his first primitive automobile, the Quadricycle, completed in 1896. A second, more sophisticated car followed in 1898. These early experiments laid the groundwork for his future endeavors in the automotive industry.

Henry Ford’s 1896 Quadricycle Runabout, the first car he built. / THF90760

Ford now demonstrated one of his most important characteristics—the ability to articulate a vision and convince other people to sign on and help him achieve that vision. He convinced a group of businessmen to back him in the biggest risk of his life—starting a company to make horseless carriages. But Ford knew nothing about running a business, and learning by doing often involves failure. The new company failed, as did a second. His first venture, the Detroit Automobile Company, failed due to the poor quality of its vehicles. Ford tried again, this time with the Henry Ford Company. But disputes over the new company’s direction soon caused Ford and his investors to part ways.

To revive his fortunes, Ford took bigger risks, building and even driving a pair of racing cars. The success of these cars attracted additional financial backers, and on June 16, 1903, just before his 40th birthday, Henry incorporated his third automobile venture, the Ford Motor Company.

The early history of Ford Motor Company illustrates another of Henry Ford’s most valuable traits—his ability to identify and attract outstanding talent. He hired a core of young, highly competent people who would stay with him for years and make Ford Motor Company into one of the world’s great industrial enterprises. He hired a core of young, highly competent people who would stay with him for years, reshaping America’s automotive industry while building Ford Motor Company into one of the world’s great industrial enterprises.

Print of Norman Rockwell's painting, "Henry Ford in First Model A on Detroit Street." / THF288551

The new company’s first car was called the Model A, and a variety of improved models followed. In 1906, Ford’s 4-cylinder, $600 Model N became the best-selling car in the country. But by this time, Ford had a vision of an even better, cheaper “motorcar for the great multitude.” Working with a small group of employees, he came up with the Model T, introduced on October 1, 1908. The Model T was a game-changer, designed to be simple, reliable, and ultimately affordable for the average American.

The Automobile: A Solution in Search of a Problem

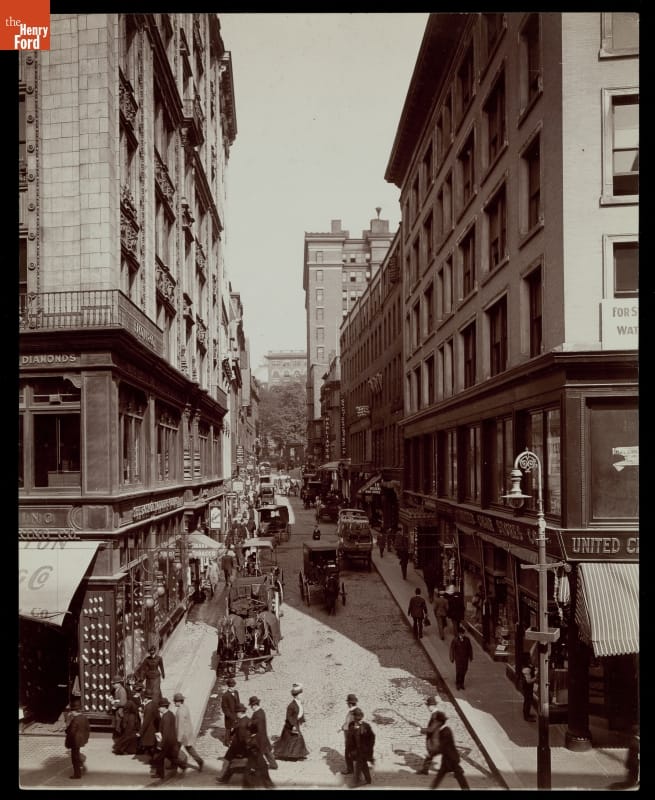

As hard as it is for us to believe, in 1908 there was still much debate about exactly what automobiles were good for. We may see them as a necessary part of daily life, but the situation in 1908 was very different. Americans had arranged their world to accommodate the limits of the transportation devices available to them. People in cities got where they wanted to go by using electric street cars, horse-drawn cabs, bicycles, and shoe leather because all the places they wanted to go were located within reach of those transportation modes.

This Boston street scene, circa 1908, shows pedestrians and horse-drawn carriages on the road—but no cars. / THF203438

Most of the commercial traffic in cities still moved in horse-drawn vehicles. Rural Americans simply accepted the limited travel radius of horse- or mule-drawn vehicles. For long distances, Americans used our extensive, well-developed railroad network. People did not need automobiles to conduct their daily activities. Rather, the people who bought cars used them as a new means of recreation. They drove them on joyrides into the countryside. The recreational aspect of these early cars was so important that people of the time divided motor vehicles into two large categories: commercial vehicles, like trucks and taxicabs, and pleasure vehicles, like private automobiles. The term “passenger cars” was still years away. The automobile was an amazing invention, but it was essentially an expensive toy, a plaything for the rich. It was not yet a true innovation.

Henry Ford had a wider vision for the automobile. He summed it up in a statement that appeared in 1913 in the company magazine, Ford Times:

“I will build a motor car for the great multitude. It will be large enough for the family but small enough for the individual to run and care for. It will be constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise. But it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one—and enjoy with his family the blessings of hours of pleasure in God’s great open spaces.”

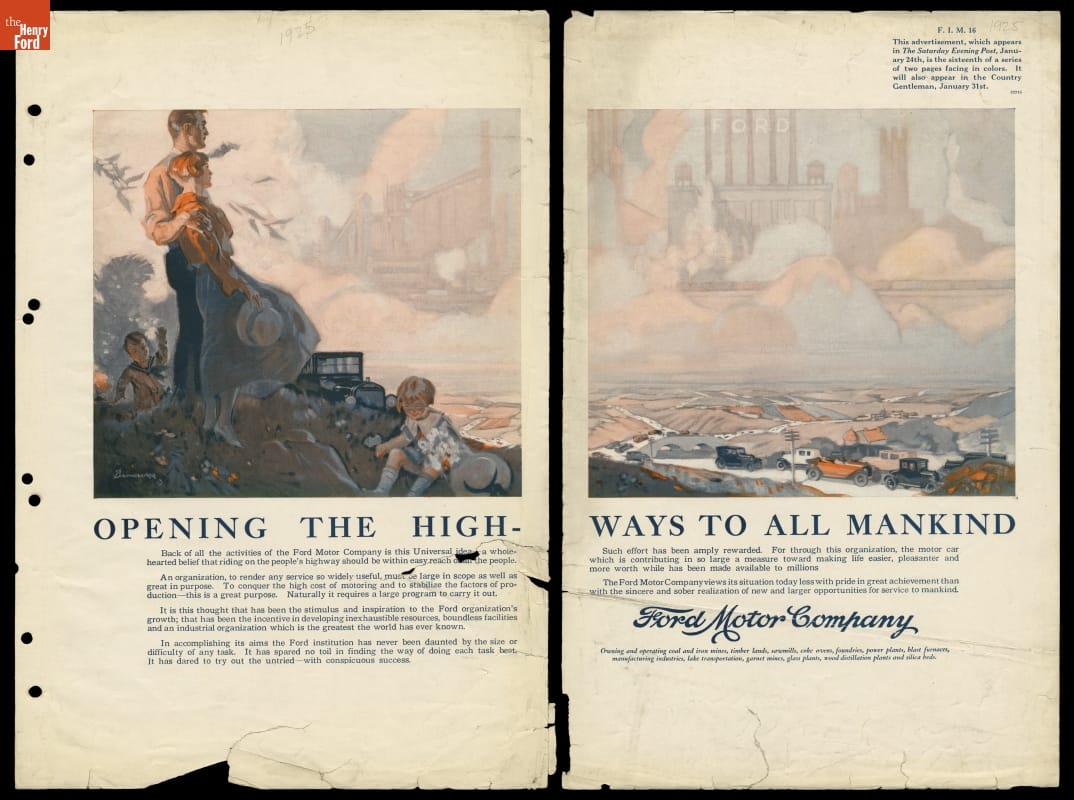

This 1924 Ford ad, part of a series, echoes the vision expressed 11 years earlier by Henry Ford: “Back of all of the activities of the Ford Motor Company is this Universal idea—a wholehearted belief that riding on the people’s highway should be in easy reach of all the people.” / THF95501

It was this vision that moved Henry Ford from inventor and businessman to innovator. To achieve his vision, Ford drew on all the qualities he had been developing since childhood: curiosity, self-confidence, mechanical ability, leadership, a preference for learning by trial and error, a willingness to take risks, and an ability to identify and attract talented people.

One Innovation Leads to Another

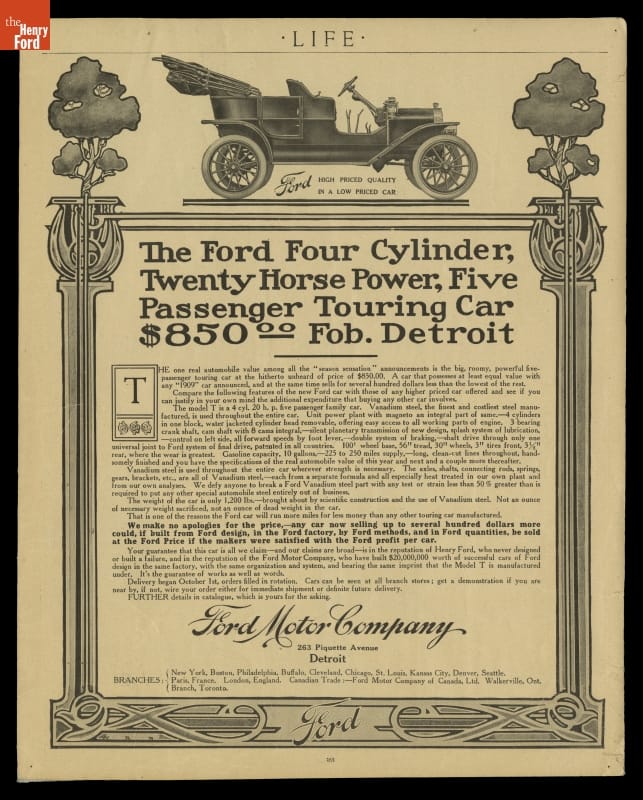

Ford himself guided a design team that created a car that pushed technical boundaries. The Model T’s one-piece engine block and removable cylinder head were unusual in 1908 but would eventually become standard on all cars. The Ford’s flexible suspension system was specifically designed to handle the dreadful roads that were then typical in the United States. The designers utilized vanadium alloy steel that was stronger for its weight than standard carbon steel. The Model T was lighter than its competitors, allowing its 20-horsepower engine to give it performance equal to that of more expensive cars. The Model T forever changed the automotive industry and American culture. Its impact can still be felt today.

1908 advertisement for the 1909 Ford Model T. In advertisements, Ford Motor Company emphasized key technological features and the low prices of their Model Ts. Ford's usage of vanadium steel enabled the company to make a lighter, sturdier, and more reliable vehicle than other early competitors. / THF122987

The new Ford car proved to be so popular that Henry could easily sell all he could make, but he wanted to be able to make all he could sell. So Ford and his engineers began a relentless drive both to raise the rate at which Model Ts could be produced and to lower the cost of production.

In 1910, the company moved into a huge new factory in Highland Park, a city just north of Detroit. Borrowing ideas from watchmakers, clockmakers, gunmakers, sewing machine makers, and meat processors, Ford Motor Company had, by 1913, developed a moving assembly line for automobiles. But Ford did not limit himself to technical improvements.

When his workforce objected to the relentless, repetitive work that the line entailed, Ford responded with perhaps his boldest idea ever—he doubled wages to $5 per day. With that one move, he stabilized his workforce and gave it the ability to buy the very cars it made. He hired a brilliant accountant named Norval Hawkins as his sales manager. Hawkins created a sales organization and advertising campaign that fueled potential customers’ appetites for Fords. Model T sales rose steadily while the selling price dropped. By 1921, half the cars in America were Model Ts, and a new one could be had for as little as $415.

Norval Hawkins headed the sales department at Ford Motor Company for 12 years, introducing innovative advertising techniques and increasing Ford’s annual sales from 14,877 vehicles in 1907 to 946,155 in 1919. / THF145969

Through these efforts, Ford turned the automobile from an invention bought by the rich into a true innovation available to a wide audience. By the 1920s, largely as a result of the Model T’s success, the term “pleasure car” was fading away, replaced by “passenger car.” Ford’s moving assembly line and $5 day ushered in a new era of mass production and affordability. American society itself was transformed as motorists were free to travel where they wanted, when they wanted.

The assembly line techniques pioneered at Highland Park spread throughout the auto industry and into other manufacturing industries as well. The high-wage, low-skill jobs pioneered at Highland Park also spread throughout the manufacturing sector. Advertising themes pioneered by Ford Motor Company are still being used today. Ford’s curiosity, leadership, mechanical ability, willingness to take risks, ability to attract talented people, and vision produced innovations in transportation, manufacturing, labor relations, and advertising. His legacy is preserved at places like Greenfield Village, showcasing his impact on American life and the evolution of the automotive industry.

What We Have Here Is a Failure to Innovate

Henry Ford was slow to admit that customers no longer wanted the Model T. However, in 1927, he finally acknowledged that shift, and Henry Ford and his son, Edsel Ford, drove this last Model T—number 15,000,000—off the assembly line at Highland Park. / THF135450

Henry Ford’s great success did not necessarily bring with it great wisdom. In fact, his very success may have blinded him as he looked to the future. The Model T was so successful that he saw no need to significantly change or improve it. He did authorize many detail changes that resulted in lower cost or improved reliability, but there was never any fundamental change to the design he had laid down in 1907.

He was slow to adopt innovations that came from other carmakers, like electric starters, hydraulic brakes, windshield wipers, and more luxurious interiors. He seemed not to realize that the consumer appetites he had encouraged and fulfilled would continue to grow. He seemed not to want to acknowledge that once he started his company down the road of innovation, it would have to keep innovating or else fall behind companies that did innovate. He ignored the growing popularity of slightly more expensive but more stylish and comfortable cars, like the Chevrolet, and would not listen to Ford executives who believed it was time for a new model.

But Model T sales were beginning to slip by 1923, and by the late 1920s, even Henry Ford could no longer ignore the declining sales figures. In 1927, he reluctantly shut down the Model T assembly lines and began the design of an all-new car. It appeared in December 1927 and was such a departure from the old Ford that the company went back to the beginning of the alphabet for a name—it was called the Model A.

Edsel and Henry Ford introduce the new Model A at the Ford Industrial Exposition in New York in January 1928. Edsel had worked to convince his father to replace the outmoded Model T with something new. / THF91597

One area where Ford did keep innovating was in actual car production. In 1917, he began construction of a vast new plant on the banks of the Rouge River southwest of Detroit. This plant would give Ford Motor Company complete control over nearly all aspects of the production process. Raw materials from Ford mines would arrive on Ford boats, and would be converted into iron and steel, which were transformed into engines, transmissions, frames, and bodies. Glass and tires would be made onsite as well, and all of this would be assembled into completed cars. Assembly of the new Model A was transferred to the Rouge. Eventually the plant would employ 100,000 people and generate many innovations in auto manufacturing. The River Rouge complex became a symbol of Ford's ambition and scale, a testament to his vision for vertically integrated production.

But improvements in manufacturing were not enough to make up for the fact that Henry Ford was no longer a leader in automotive design. The Model A was competitive for only four years before needing to be replaced by a newer model. In 1932, at age 69, Ford introduced his last great automotive innovation, the lightweight, inexpensive V-8 engine. It represented a real technological and marketing breakthrough, but in other areas Fords continued to lag behind their competitors. The Ford factory continued to evolve, but the company faced new challenges in keeping up with changing consumer preferences and technological advancements in the automotive industry.

The V-8 engine was Henry Ford’s last great automotive innovation. This is the first V-8 engine produced, which is on exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF101039

By 1936, the company that once sold half of the cars made in America had fallen to third place behind both General Motors and the upstart Chrysler Corporation. By the time Henry Ford died in 1947, his great company was in serious trouble, and a new generation of innovators, led by his grandson Henry Ford II, would work long and hard to restore it to its former glory. Henry’s story is a textbook example of the power of innovation—and the power of its absence. His contributions to the automotive industry and American society are undeniable, but his later resistance to change serves as a cautionary tale.

Bob Casey is former Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. This post is adapted from an educational document from The Henry Ford titled “Henry Ford and Innovation: From the Curators.”

Detroit, Michigan, Dearborn, 20th century, 19th century, quadricycle, Model Ts, manufacturing, Henry Ford, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Ford Motor Company, entrepreneurship, engines, engineering, cars, by Bob Casey, advertising

If you’re ready to bring more innovative thinking, collaboration and can-do spirit to your virtual meetings? These background images will help you conduct your meeting in the original environments that are part of The Henry Ford collections and experiences. They include Thomas Edison’s lab, the Wright Brothers Cycle Shop, Mathematica, Dymaxion House, an 18th-century farmhouse, railroad roundhouse and a real automotive factory.

You can download additional backgrounds from our digital collections.

Here are the instructions to set the images below as your background on Zoom or Microsoft Teams.

Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation

Dymaxion House

Driving America Continue Reading

Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 2010s

As the 21st century began, The Henry Ford’s automotive exhibit, Automobile in American Life, was into its second decade of life, and needed a refresh. In a major change that affected 80,000 square feet on the Museum floor, Driving America roared into life in January of 2012.

Not only were the themes and artifacts included in the exhibit completely rethought, but digital technologies were integrated from the beginning to fuel touchscreen kiosks containing activities, curator interviews, and tens of thousands of digitized artifacts from The Henry Ford’s collections—including a substantial new set of glamour shots for each vehicle in the exhibit. This first big experiment with digitized collections within an exhibit is forming the basis for the use of interactive technologies in upcoming exhibits.

Technology Accelerates at the Rouge

In late 2014, Ford Motor Company began producing the first mass-produced truck in its class featuring a high-strength, military-grade, aluminum-alloy body and bed after having completely redesigned its F-150 assembly line at the Ford Rouge plant. This posed a challenge for the Ford Rouge Factory Tour—the manufacturing story had completely changed. An overhaul of the entire experience involved updated experiences in both theaters, particularly in the Manufacturing Innovation Theater, offering a multisensory, multidirectional show. An interactive kiosk, similar to those installed in Driving America, was also installed to allow visitors to access The Henry Ford’s digital collections with the touch of a finger.

Village Growth

While the Village has not yet seen any more changes as substantial as those that occurred in the early part of the 21st century, the period since 2010 has brought a couple of notable upgrades to the working districts of Greenfield Village. One was the 2014 addition of a 50-foot-tall coaling tower, based on historic designs and used to store and load coal into the historic operating locomotives of Greenfield Village.

The other recent project was the physical expansion of the Pottery Shop in 2013, a project sparked by the need to replace a salt kiln that was nearly three decades old. The kiln room was rebuilt and slightly expanded, and by reconfiguring the layout, a spacious area for the decorators to work was also created.

Anniversaries and Remembrances

Despite the growth in digital experiences, the power of physical artifacts is still undeniable. Many significant anniversaries related to the objects and stories of The Henry Ford have been observed with events within Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village in recent years.

One of the largest and most notable was the Day of Courage, celebrated with an all-day event on February 4, 2013. Historians, musicians, students, and Museum guests remembered the life of Rosa Parks on her 100th birthday. In November 2013, lectures by newscaster Dan Rather and former Secret Service agent Clint Hill, as well as an opportunity to visit the fateful limousine, formed a remembrance of President John F. Kennedy on the 50th anniversary of his assassination. April 2015, the 150th anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, was marked with a lecture by historian Doris Kearns Goodwin and the first removal of the Lincoln chair from its display case in decades.

Innovation Focus

Our collecting continues to focus on resourcefulness, innovation, and ingenuity—and both new and old artifacts, along with their stories, are featured in new ways. In particular, as digital technologies became ubiquitous, The Henry Ford began developing new strategies to accomplish its mission to share, teach, and inspire, particularly focused on the “innovation” portion of the mission statement.

The Henry Ford Archive of American Innovation™ represents the core assets of The Henry Ford that illustrate the process and context of innovation. It refers to artifacts and documents in the collection that provide an unprecedented window into America’s traditions of resourcefulness, innovation, and ingenuity. It is the key to understanding how our entire modern world was created.

Related stories of artifacts and innovation are featured on The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation, a weekly educational TV program produced by Litton Entertainment and hosted by Mo Rocca, which has aired since Fall 2014. Innovation is also brought in through events such as Maker Faire Detroit, hosted annually at The Henry Ford since 2010.

Active Collecting

Though the world has become increasingly digital, The Henry Ford continues to collect hundreds or even thousands of physical artifacts each year. In the second decade of the 21st century, this has included material related to significant artifacts we already hold (John F. Kennedy material, to add additional context to the Kennedy Limousine; and the George Devol collection, which relates to the world’s first industrial robot), design (an Eames-designed, IBM-used kiosk and hundreds of examples of 20th century soap packaging), and auto racing (photographic collections from John Clark and Ray Masser and dozens of tether cars or “spindizzies”).

Major recent acquisitions include the John Margolies Roadside America collection, the Bachmann studio collection of American glass, the Roddis clothing collection, and Mathematica, a circa 1960 exhibit designed by Charles and Ray Eames.

The Collections Go Digital

The Henry Ford began scaling up its collections digitization effort in 2010, hiring new staff with new skills to advance this technology-intensive effort that involves conservation, cataloging, photography, and scanning. Images of tens of thousands of artifacts are now freely available online, from our Digital Collections, and provide the basis for additional layers of supporting content, helping the public to understand artifacts in the context of their original time and place as well as the context of today.

Digitization efforts include artifacts on display within the Museum or Village, new acquisitions, and “hidden” items currently in storage. In 2013–15, for example, more than 1,200 communications-related artifacts in storage, including many significant rediscovered treasures, were digitized through a grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

From Digital Artifacts to Digital Stories

While more than 20,000 artifacts are on public exhibit in Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, the Benson Ford Research Center, and the Ford Rouge Factory Tour, The Henry Ford’s collection holds many more—about 250,000 objects and millions more photographs and documents within our archives. Institutional commitment to the digitization of The Henry Ford Archive of American Innovation™ is making these collections, and the ideas behind them, more accessible to more people in more ways than ever.

Acquisitions Made to the Collections - 2010s

Apple 1 Computer, 1976

In 2013, The Henry Ford acquired an Apple 1 computer—one of the first fifty ever made, and fully operational. This groundbreaking device documents an important “first,” as one of the earliest desktop computers to be sold with a pre-assembled motherboard (although users had to purchase a separate keyboard, monitor, and power source). The Apple 1 is also the beginning of something in the sense that it led to the founding of one of today’s most successful computer companies in the world. This artifact demonstrates The Henry Ford’s commitment to collecting the hardware, software, and the ephemeral culture that powers the digital age. You can see a video describing the Apple 1 acquisition and the process of booting it up here. - Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communication & Information Technology

Throstle Spinning Frame

This rare spinning frame was part of a landmark acquisition, perhaps the largest since Henry Ford’s time--nine truckloads of textile history-related objects and archival materials! Spinning frames like this circa 1835 example--likely the earliest surviving American industrial textile machine--helped spin the large quantities of thread that growing industrial weaving operations needed in the early and mid-19th century. In 2016, the American Textile History Museum in Lowell, Massachusetts closed its doors and began to transfer their collections to other organizations. The Henry Ford was among them--able to provide a home for many thousands of objects dating from the 18th to 21st centuries: textile machinery and tools, clothing and domestic textiles, and hundreds of sample books of printed fabrics from several major New England companies. This rich collection from ATHM tells the story of a key player in America’s Industrial Revolution--the textile industry. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

La-Z-Boy Reclina Rocker

La-Z-Boy is a story of technological innovation, marketing, and sales savvy. Two cousins created the first chair in the late 1920s but didn’t gain acclaim until the 1960s with the Reclina Rocker, which combined a built-in ottoman with a rocking feature. Multi-faceted promotional strategies, including celebrity endorsements, caught the eye of middle-class Americans, who eagerly bought the chair for their homes. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

2016 General Motors First-Generation Self-Driving Test Vehicle

Self-driving cars have the potential to reduce accidents, ease traffic, reduce pollution, and improve mobility for people unable to drive themselves. Assuming we can solve the remaining technical, legal, and psychological challenges, autonomous cars promise to bring the most significant change in our relationship with the automobile since the Model T itself. This experimental vehicle represents General Motors' first major step toward our autonomous future -- and The Henry Ford's first major step to document the journey. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

Ruth Adler Schnee Textiles

Designer Ruth Adler Schnee's modern textiles are bold, colorful, and pushed the mid-20th century modern design movement forward. She drew inspiration from the world around her, the ordinary as well as the extraordinary. The Henry Ford's acquisition of her textiles in 2000 and in 2018 speak to her continued relevance to our collection-- as a modern design pioneer, a female entrepreneur, and a Jewish immigrant. - Katherine White, Associate Curator

Robert Propst Papers

Noted industrial designer Robert L. Propst is best known for his work with Herman Miller and for designing the “Action Office,” an office furnishing system which became the basis for the modern cubicle. Propst’s papers cover the design and business aspects of “Action Office” as well many of his other projects such as a residential housing system, hotel housekeeping carts, hospital furniture, an industrial timber harvester, and even children's playground equipment. - Brian Wilson, Sr. Manager, Archives and Library

Champion Egg Case Machine, 1900-1925

This artifact furthers The Henry Ford's mission in several ways –it’s the product of an innovator. James Ashley first patented a box-making machine in 1892. Resourceful farm families with eggs to sell built boxes with this machine, marked the contents "farm fresh," and shipped their product to meet the growing demand of chicken-less urban consumers. The machine created a standardized box which held 12 flats (six on each side). Each flat held 30 eggs for a total of 360 eggs (30 dozen) in one box. Consumers today eat eggs transported to market on flats in boxes similar to the ones this machine was designed to build. Ashley's egg-case maker helps document the long history of farm-market exchange that responded to wary consumers' concerns over the freshness of the agricultural product. - Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

events, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, THF90

Paint a Bigger Picture

Image courtesy of the Ford Motor Comany Archives

The Fumes to Fuel program at Ford Rouge Complex strives to make the process of adding color onto cars more environmentally friendly.

Take the Ford Rouge Factory Tour, and a number of sustainable, environmentally conscious manufacturing practices and processes jump out at you right away. You’ll see the Dearborn Truck Plant’s massive living roof and purposeful use of natural light. You can even walk the surrounding outdoor sanctuary where birds nest, flowers bloom and honeybees flourish.

“What really impresses me is Ford’s continued commitment to tackle big issues and figure out new processes and ways of doing things that not only make it better for the product but also address air and water issues,” said Cynthia Jones, general manager of the Ford Rouge Factory Tour. “Ford is pushing the paint industry to make paints better, and it is also pushing to make its own processes better.”

Solvents in the paint used to coat vehicles wind up in the exhaust system, and what’s left is “nasty stuff,” according to David Crompton, a senior environmental engineer at Ford Motor Company. “A lot of countries will not permit the discharge of it into the atmosphere,” he added, “so our early work focused on developing ways of abating those solvents.”

The Fumes to Fuel process, which has been refined over several years, pushes solvent-laden exhaust air through a carbon bed. The carbon removes the solvents from the exhaust, leaving behind clean exhaust that can be safely discharged into the atmosphere. The carbon is then swept with nitrogen, heating it up and removing the solvents. The carbon returns to the absorption stage, and the solvent-laden nitrogen is condensed into a liquid form.

The entire process ends up being more environmentally friendly than producing water-based coatings, because less energy is required and the potentially harmful solvents are abated.

“Some of our competitors chose water-based coatings,” Crompton said. “We believe that solvent-born technology provides the best overall environmental performance because the technology requires less energy consumption, which translates into lower CO2 emissions. It also allows lower facility and operating costs, so there’s a smaller overall footprint.”

Another added benefit, the solvent-born coatings give Ford vehicles a best-in-class finish in terms of durability and chip and scratch resistance.

Did You Know?

The Ford Rouge Factory Tour’s Manufacturing Innovation Theater received a 2016 Thea Award for outstanding achievement for a brand experience. The Thea awards program honors creative excellence in theme parks, museums and other attractions, and is considered one of the attraction industry’s greatest honors.

This story originally ran in the June-December 2016 edition of The Henry Ford Magazine.

manufacturing, cars, environmentalism, The Henry Ford Magazine, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Ford Motor Company

In 1915, Henry Ford began acquiring property along the Rouge River in southeastern Michigan with the intent of building a vast manufacturing complex, aiming to transform raw materials into parts and those parts into automobiles in the most rapid and efficient possible ways. The first major building on the site was constructed in 1917, but work to extend and expand the Rouge plant and its capabilities continued through the 1920s. We’ve just digitized 119 images taken between February and May 1918 that focus on the construction going on at the Rouge, including many like this one that give a sense of the expansive nature of the endeavor. Visit our Digital Collections to see these Rouge images and others from our Automobile Plant Construction Photographs collection, or learn more about the modern Rouge and how you can see the plant yourself on our visit page.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

digital collections, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Ford Motor Company, by Ellice Engdahl

House of Glass

![Ford's New-Model Quality Center MS37640[1] Ford's New-Model Quality Center MS37640[1]](/SitefinityImages/0x0-44c54e84-d30d-6b61-be8b-ff010073bae4.jpg)

Photo courtesy of Ford Motor Company Archives.

Restored architectural gem stands out in its industrial space

You don’t usually associate large manufacturing factories with architectural beauty. Sightseers at the Ford Rouge Complex’s glass plant, however, might be inclined to think otherwise.

This plant looks different. No concrete, only rivets and steel. From inside, the high roof and floor-to-ceiling windows create an unusually airy, spacious atmosphere. Natural light can’t help but stream in, creating a softness and easy glow.

Designed by famed American industrial architect Albert Kahn, the Ford Rouge’s glass plant was built in 1923 as an automotive glass-production facility. “It was about achieving volume,” Don Pijor, launch manager at the Dearborn Truck Plant and site expert for the glass plant, said of the building’s original design. “This space was built with steel columns riveted together, which gives it much more usable real estate.”

In the late ‘90s, the 40,000-square-foot building was taken out of the complex’s production equation, its sweeping windows covered with aluminum and its new primary purpose as a warehouse.

When the restoration process began in the mid-2000s, the original intent was to transition the building into office space. Pijor later helped persuade Ford Motor Company leadership to put the plant to better use as a prove-out and employee training building for the Ford F-150, the truck built at the Rouge’s Dearborn Truck Plant.

Careful decisions were made at every corner during the restoration. The building’s window glass, for example, had come from Europe, so the restoration team reached out overseas to the original manufacturer for the glass to replace the windows. Entry doors to a fire station that was part of the building’s layout were also replaced to replicate those of the original specs.

“It’s beautiful,” Cynthia Jones, The Henry Ford’s Ford Rouge Factory Tour manager, said of the glass plant today. “There’s lots of natural light, and even though the fire station doors are in an area the public doesn’t see, restoring them showed respect for the continuing history of the site.”

Today, the glass plant is a house for innovation, used for prototyping by Ford engineers and designers. As a result of its newfound purpose, the building’s glass at the lower levels is frosted so outsiders can’t see the confidential work being done inside.

Said Jones of balancing the building’s historical integrity with its modern uses, “When you’re making choices about restoring buildings, you look at product — what is it we’re making at this place and what does it need? You’re also employee-driven because if they can’t do their job well here, changes have to be made. Third, how does it affect the area around it? I think this site has that balance.”

Though the effectiveness of the plant’s current functions are at the forefront of any decision-making about its form, preserving its history is meaningful for the people who work there as well as for posterity. Added Pijor, “To sit in this space and watch flaming ore cars go by, it’s as if it has been like this for 100 years.”

Ford Rouge Glass Plant, 1927. THF 113886

Ford Rouge Glass Plant, 1927. THF 113886

National Historic Landmark

The Ford Rouge Complex was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1978.

The rare designation (with just 2,500 historic landmarks nationwide) usually restricts future changes to a site. The Ford Rouge Complex, however, is recognized as remaining in continual operation, which means the designation can be maintained even as the site continues to evolve.

“It’s important for the public to be aware” of the designation, said Jones. The designation is marked at the complex’s entry with a plaque and a statue of Henry Ford.

Summer 2015 marked 100 years since Ford started acquiring the property which the Rouge now inhabits. “We’re carving out space within this giant industrial complex to recognize its history and the history of the hundreds of thousands of people that have been employed here,” said Jones.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 20th century, manufacturing, glass, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Ford Motor Company, design

The Henry Ford Launches on Google Cultural Institute

We're very pleased to announce that we are launching a new partnership between The Henry Ford and the Google Cultural Institute, available to anyone with Internet access here. The Google Cultural Institute platform features over 1,000 cultural heritage institutions worldwide, and more than 6 million total artifacts, “putting the world’s cultural treasures at the fingertips of Internet users and … building tools that allow the cultural sector to share more of its diverse heritage online” (in Google’s own words). Continue Reading

technology, 21st century, 2010s, Greenfield Village, Google Arts & Culture, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, by Ellice Engdahl, African American history