Posts Tagged greenfield village

Mrs. Cohen: A Fashion Entrepreneur

Life is often a juggling act of work, play and family. While current-day clothiers experience the trials and tribulations of being small-town entrepreneurs in the big business of fashion, more than 100 years ago many women were facing similar circumstances, leaning on their sense of style to furnish a living.

In the late 1800s, Elizabeth Cohen had run a millinery store next to her husband’s dry goods store in Detroit. When he died and left her alone with a young family, she consolidated the shops under one roof. Living above the store, she was able to run a business and earn a living while staying near her children.

Cohen leveraged middle-class consumers’ growing fascination with fashion, using mass-produced components to create hats in the latest styles and to the individual tastes of customers. To attract business, resourceful store owners like Mrs. Cohen displayed goods in storefront windows and might have advertised through trade cards or by placing advertisements in newspapers, magazines or city directories.

“While Mrs. Cohen was more likely following fashion than creating it, it did take creativity and design skill,” Jeanine Head Miller, curator of domestic life at The Henry Ford, said of Cohen’s millinery prowess. “She was a small maker connecting with local customers in her community — a 19th-century version of Etsy, perhaps, but without the online reach.”

And she certainly gained independence and the satisfaction of supporting her family while selling the hats she created from the factory-produced components she acquired. “People can appreciate the widowed Elizabeth Cohen’s balancing act,” added Miller, “successfully caring for her children while earning a living during an era when fewer opportunities were available to women.”

Jennifer LaForce is a writer for The Henry Ford Magazine. This story originally appeared in the June-December 2016 issue.

19th century, women's history, The Henry Ford Magazine, shopping, Michigan, making, hats, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, fashion, entrepreneurship, Detroit, design, Cohen Millinery, by Jennifer LaForce

Starting and Ending with Henry

Some time ago, The Henry Ford’s digitization team started a project to digitize selected photographs of Greenfield Village buildings. More than 2800 photos and two years later, we have finally completed this project, a celebration marked by the team with mini-cupcakes and commemorative coasters featuring some of our favorite images from the project.

While all the buildings have a strong relationship to Henry Ford—the majority were selected by him and added to the Village under his watch—the final building we imaged is one of the most important to Henry’s story: his birthplace. We imaged over 175 photos of Ford Home, including this November 5, 1920 shot of the house on its original site.

Visit our Digital Collections and search on any building name to see more—or see some staff favorite photos in our Expert Set.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Henry Ford, by Ellice Engdahl, digital collections

Now Open: Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery

When Charles Sable, curator of decorative arts, was tasked with updating The Henry Ford's American glass collection, he accepted the challenge with enthusiasm. He envisioned creating an all-new gallery on the grounds of The Henry Ford, a place to exhibit portions of the institution's 10,000 glass artifacts currently in storage.

The gallery would also give him a strong talking point with Bruce and Ann Bachmann, private collectors of one of the most important Studio Glass collections. According to Sable, the Studio Glass Movement, which originated in the early 1960s, is recognized as a turning point in the history of glass as artists explored the qualities of of the medium in a studio environment. Their goal was to create fine art, in place of craft or mass produced objects.

While other museums were interested in the Bachmann Collection, it was The Henry Ford that garnered their full attention. "The Bachmanns had very specific criteria for their collection," said Sable. "They were looking for an institution that was in an urban area, preferably in the Midwest where they live, had a large visitation, and was capable of exhibiting and maintaining the collection."

After years of hard work, The Henry Ford recently added the Bachmann glass collection to its Archive of American Innovation. "As Bruce [Bachmann] told me, it was a good marriage," noted Sable of the donation. "He felt his collection would live here in perpetuity."

This month, the story of the Studio Glass Movement becomes a permanent exhibit in Henry Ford Museum with the opening of the Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery. "Our exhibit is a deep dive into how Studio Glass unfolded," said Sable. "It's the story of the combination of science and art that created a new and innovative chapter in the history of glass. As a history museum we look at the impact of Studio Glass on everyday life – we will include a section on mass-produced glass influenced by Studio Glass, but sold by retailers such as Crate and Barrel, Pier 1 Imports and others."

With donor support and fundraising, Sable's vision for an all-new glass gallery in Greenfield Village is also a reality. The Gallery of American Glass will open in the Liberty Craftworks District in spring 2017, giving thousands of visitors the opportunity to see the artistry and evolution of American glass through artifacts, digitized images and interactive displays.

Did You Know?

The Bruce and Ann Bachmann Studio Glass Collection numbers approximately 300 pieces, with representation of every artist of importance, including Paul Stankard, Harvey Littleton and Toots Zynsky.

The all-new Gallery of American Glass is a careful redesign of the McDonald & Sons Machine Shop in Greenfield Village's Liberty Craftworks District. The Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery in Henry Ford Museum is located in the hall that once displayed the sliver and pewter collection.

Additional Readings:

- Vase Made by Harvey K. Littleton at the Second Toledo Museum of Art Glass Workshop, 1962

- "Devils Blowing Glass" by Lucio Bubacco, 1997

- Tiffany and Art Glass

- Artist in Residence: Shelley Muzylowski Allen

Greenfield Village, Henry Ford Museum, philanthropy, art, glass

The First of Its Kind

Hanks Silk Mill was acquired by Henry Ford in 1929, moved to Greenfield Village in 1931, and reconstructed in 1932, with a grove of mulberry trees (the standard diet of silkworms) planted nearby in 1935. The mulberry grove still stands, but the mill is a fairly small, unassuming-looking building, which belies the “firsts” in its history. Established in 1810, it is believed to be the first water-powered silk mill in the United States, and perhaps also to have produced the first machine-made silk.

As part of our ongoing effort to digitize photos of the buildings of Greenfield Village, we’ve just digitized over a dozen images of the Hanks Silk Mill, including this 1931 photo of the mill on its original site, with a sign proudly proclaiming its heritage. Visit our Digital Collections to view all the newly digitized images.

manufacturing, fashion, by Ellice Engdahl, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, digital collections

A Wardrobe Workshop

Visit Greenfield Village and you can’t help but notice the clothing. From the colonial-era linen garments worn by the Daggett Farmhouse staff as they go about their daily chores to the 1920s flapper-style dresses donned by the village singers, or even the protective clothing worn by the pottery shop staff in the Liberty Craftworks district — all outfits in Greenfield Village are designed to add to the guest experience. In many cases, these tangible elements help accurately showcase the time period being interpreted.

“Clothing is such a big part of history,” said Tracy Donohue, general manager of The Henry Ford’s Clothing Studio, which creates most of The Henry Ford’s reproduction apparel and textiles for daily programs as well as seasonal events. “It’s a huge part of how we live even today. The period clothing we provide helps bring to life the stories we tell in the village and enhances the experience for our visitors.”

The Clothing Studio is tucked away on the second floor of Lovett Hall. It provides clothing for nearly 800 people a year in accurate period garments, costumes and uniforms, and covers more than 250 years of fashion — from 1760 to the present day — making the studio one of the premier museum period clothing and costume shops in the country.

The scope and flow of work in the studio is immense, from outfitting staff and presenters for the everyday to clothing hundreds for extra seasonal programs such as Historic Base Ball, Hallowe’en and Holiday Nights. Work on the April opening of Greenfield Village, for example, begins before the Holiday Nights program ends in December, with the sewing of hundreds of stock garments and accessories in preparation for hundreds of fitting sessions for new and current employees.

“When it comes to historic clothing, our goal is to create garments accurate to the period — what our research indicates people in that time and place wore,” said Donohue. “For our group, planning for Hallowe’en is an especially fun challenge. We have more creative license with costumes for this event than we typically do with our daily period clothing.”

For Hallowe’en in Greenfield Village, the studio staff researches new characters and can work on the design and development for more elaborate wearables for months. In addition to new costume creation, each year existing outfits are refreshed and/or reinvented. Last year, for example, the studio added the Queen of Hearts, Opera Clown and a number of other new characters to the Hallowe’en catalog. Plus, they freshened the look of the beloved dancing skeletons and the popular pirates.

Historic clothing, period photographs, prints, trade catalogs and magazines from the Archive of American Innovation provide a wealth of on-site resources to explore the styles, clothing construction and fabrics worn by people decades or centuries ago. Each year, Jeanine Head Miller, curator of domestic life, and Fran Faile, textile conservator, host the studio’s talented staff for a field trip to the collections storage area for an up-close look at original clothing from a variety of time periods.

“Getting the details right really matters,” Miller said. “Clothing is part of the powerful immersive experience we provide in Greenfield Village. Having people in accurate period clothing in the homes and the buildings helps our visitors understand and immerse themselves in the past, and think about how it connects to their own lives today.”

Did You Know?

The Clothing Studio has a comprehensive computerized inventory management system, which tracks close to 50,000 items.

During each night of Hallowe’en, Clothing Studio staff are on call, checking on costumed presenters throughout the evening to ensure they look their best.

What They're Wearing Under There

At Greenfield Village, costume accuracy goes well beyond what’s on the surface. Depending on the time period they’re interpreting, women may also wear chemises, corsets and stays.

“Our presenters have a lot of pride in wearing the clothing and wearing it correctly,” said Donohue.

While the undergarments function in the service of historic accuracy, corsets also provide back support and chemises help absorb sweat. Natural fibers in cotton fabrics breathe, so they’re often cooler to wear than modern-day synthetic fabrics. And when the weather runs to extreme cold conditions, layers of period-appropriate outerwear help keep village staff warm. The staff at the Clothing Studio also sometimes turns to a few of today’s tricks to keep staff comfortable. Wind- and water-resistant performance fabrications are often built into Hallowe’en costumes to offer a level of protection from outdoor elements.

“It can be 100 degrees in the summer and 10 degrees on a cold Holiday Night,” Donohue said. “Our staff is out in the elements, and they still have to look amazing. We care about the look and overall visual appearance of the outfit, of course, but we also care about the person wearing it.”

From The Henry Ford Magazine. This story originally ran in the June-December 2016 issue.

Hallowe'en in Greenfield Village, events, Greenfield Village, making, costumes, fashion, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, The Henry Ford Magazine

An Educator Admired by Henry Ford

We are closing in on the end of our multi-year project to digitize photographs related to the buildings in Greenfield Village, and one of the most recent buildings we’ve tackled has been the William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace. In the 1830s, McGuffey created a series of textbooks commonly known as McGuffey’s Readers, intended to teach reading and writing to various grade levels of schoolchildren. Henry Ford used these readers as a child and considered them an important influence in his life, so he moved the Washington County, Pennsylvania birthplace of McGuffey to Greenfield Village in the early 1930s, dedicating it on September 23, 1934, the 134th anniversary of the author’s birth. Among the several dozen images we’ve just digitized is this 1845 portrait of Harriet Spining McGuffey, who became William Holmes McGuffey’s wife in 1827.

Visit our Digital Collections to view all of the newly digitized images, or browse through other McGuffey-related artifacts, including a number of McGuffey Readers.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Henry Ford, Pennsylvania, 19th century, 1830s, William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, education, digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl, books

Although medical history is not currently a focus of The Henry Ford’s collections, we do have numerous medical artifacts because they relate in some way to a different area of our collections, such as public life, transportation, buildings and architecture, or design. New Associate Curators of Digital Content, Katherine White and Ryan Jelso, combed through The Henry Ford’s collection looking for artifacts that were medically innovative, either as physical innovations or as representations of innovations in the medical profession. The objects they found were initially acquired for their relation to a different collections area, but they tie closely to the development of today's medical technologies and practices.

A Civil War surgeon used this government-issued Field Operating Kit, initially acquired by The Henry Ford as a public history artifact, at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May of 1863. It contains all the tools needed to perform the most common Civil War medical procedure – amputation.

New Weapons Technology Leads to New Surgical Techniques

In 1849, French military officer Claude-Etienne Minié invented a hollow-based cylindrical bullet, which was more accurate over long distances than its predecessors and more quickly loaded into a rifle barrel due to its slightly smaller size. The minié bullet provided a significant advantage to those on the offensive; however, the bullet was immensely destructive to those on the defensive. Due to its hollow nature, the projectile became misshapen upon impact and its ragged edges caused significantly more internal damage than the solid bullets used previously.

Both the Union and Confederate Armies utilized the minié bullet extensively during the American Civil War. The damages wrought by this particular bullet surely contributed to the war’s astronomical death count, but also contributed to the advancement of amputation surgery. While amputation had been used throughout the ages, Civil War surgeons innovated numerous surgical advancements. Immediate amputation of an injured limb before infection spread to healthy tissue became standard and drastically decreased battlefield mortality rates.

The Henry Ford's broad transportation collection covers the motorization of ambulances during World War I. Take a look at a few archival photographs that document the Model T's role in this important part of ambulance history, here.

The Motorization of Medical Care

The Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries spurred technological innovations that would change how wars were conducted in the decades to come. By the beginning of World War I in the early 20th century, military units had become increasingly motorized, replacing the horses and wagons of past wars. Armies employed mechanized military vehicles like tanks, airplanes and submarines along with new forms of chemical warfare to inflict mass casualties during what became known as "The Great War." With a surge in casualties, quick transportation of the wounded away from the battlefronts to safer hospitals became a life-saving priority. To meet this need, volunteer services and individual armies experimented with and developed motor ambulance corps, eventually making them commonplace.

The torn up roads, heavily shelled areas, and muddy terrain of the war-torn European continent made lighter vehicles preferable. While other makes and models were present, lightweight Ford Model Ts made up a large percentage of the ambulances in service during World War I. The vehicles’ ability to traverse the war environment along with their easy maneuverability made them popular among ambulance drivers. Other advantages of Model T ambulances included their low cost, economical fuel usage, and ease of operation for the average solider or volunteer. The standardization of Model T parts also meant that maintenance for these ambulances could be performed readily, extending each vehicle's service life and allowing medical professionals to tend to the wounded quicker than ever before.

As a part of the historic building collection in Greenfield Village at The Henry Ford, Doc Howard's office serves as an example of the 19th century origins from which modern American medicine would evolve.

A Snapshot of Mid-19th Century Medicine

Representative of a typical early rural doctor's office, this mid-19th century building is where Dr. Alonson Bingley Howard (1823-1883) practiced an eclectic combination of conventional, botanical, and homeopathic medicine. Born in New York, Howard moved to Tekonsha, Michigan, and began his career as a farmer, eventually deciding that he wanted to become a physician. He first attended Cleveland Medical College from 1850-1851, later entering the University of Michigan's School of Medicine, where he took classes from 1851-1852. Although medical school records list him as a non-graduate, Howard moved back to Tekonsha and went on to practice medicine until his death in 1883.

In the 19th century, medical professionals had a limited understanding of illnesses and often relied on bloodletting or other purging methods to "balance" the body and keep diseases at bay. Along with minor surgery, these common practices were available to Dr. Howard as he traveled across his community attending to pregnancies, chronic diseases, tuberculosis, dental problems, and various wounds. To aid him in treating his patients, he relied on the early pharmaceutical medicines that could be found on the market during this period. However, he also kept a laboratory in his office where he could experiment with developing his own medicines through a wide personal stock of plants and minerals.

The Henry Ford obtained this Eames Molded Plywood Leg Splint as a design history artifact. It can be found in design museums throughout the world and is included in The Henry Ford Museum’s “Fully Furnished” exhibit.

Experimentation with Plywood Provides Medical Solution

The Museum of Modern Art held a design competition in 1940 entitled Organic Design in Home Furnishings, which aimed to spur development of modern furniture that adequately addressed the era’s changing way of life. Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen, friends and peers at Michigan’s Cranbrook Academy of Art, entered multiple molded plywood chair designs into the competition and won two of the six categories. At the time, molding or bending plywood was still a quite progressive process and molded plywood was not yet commonly used in mass-produced goods for the public. Along with his wife, Ray, Charles Eames continued experimentation with molded plywood after the competition.

America’s entry into World War II brought shortages of many materials, including metal. Splints for broken limbs had historically been produced of metal, although metal splints were not ideal for military use due to their weight and inflexibility. Charles and Ray Eames, perpetual problem-solvers, designed a lightweight, strong, and flexible leg splint produced through their innovative method of molding plywood. The Eames molded leg splint became a highly effective solution for the military as well as a highly sculptural design object.

Represented in The Henry Ford's large American public life collection is the late 19th- and early 20th-century phenomenon of patent medicines, over-the-counter drugs that consumers used to self-medicate.

Consumerism Helps Standardize Early Medicines

In the late 19th century, an increasing body of medical knowledge had begun to revolutionize the practice of medicine. However, a lack of scientific understanding of early medical drugs meant that drugs used in treatment were often inadequate and could even exacerbate illnesses. At a time when disease was still widespread, Americans sought cures for any number of maladies and tried nearly anything to get relief. Entrepreneurs took advantage, using advertising to make claims and promise cures with manufactured patent medicines. Such patent medicines rose to popularity in the last quarter of the 19th century, but the industry was unregulated and manufacturers were secretive about their recipes.

Some of these concoctions contained harmful ingredients or ingredients used in unsafe quantities. Cocaine, alcohol, opium, and heroin were some of the common ingredients that could be found in early patent medicines. These examples, as well as other additives, could result in addiction or even death, prompting national legislation that prohibited misleading health claims and required manufacturers to list their product's contents. In the United States, the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 helped stop the manufacture of drugs and products considered poisonous, adulterated or mislabeled.

Some of the patent medicines in our collection were analyzed in 2013 through a partnership between The Henry Ford's conservation staff and the Chemistry & Biochemistry Department at University of Detroit Mercy. Their findings, as well as more information on patent medicines can be found here in our Digital Collections.

An artifact, especially an innovative artifact, often has multidisciplinary significance. An object that is distinctly medical in nature may be equally as significant, or even more significant, as a public history or design history artifact. The Henry Ford’s collections boast countless significant artifacts with histories that reach across subject matter boundaries, such as this grouping of medically innovative artifacts.

By Katherine White and Ryan Jelso, Associate Curators, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. This post was made possible in part by our partners at Beaumont. Beaumont is a leading high-value health care network focused on extraordinary outcomes through education, innovation and compassion. For the latest health and wellness news, visit beaumont.org/health-wellness.

20th century, 19th century, patent medicines, healthcare, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Eames, Dr. Howard's Office, design, by Ryan Jelso, by Katherine White

In the late 1880s, German immigrant Engelbert Grimm had a building designed by local architect Peter Dederichs, Jr., which was then built along Michigan Avenue in Detroit’s Corktown neighborhood. Grimm sold and repaired watches, clocks, and jewelry for more than four decades on the ground floor of this building, and lived with his family on the second floor. After the death of the store’s founder, customer Henry Ford acquired both the contents of the store and, later, the building itself, which now stands in Greenfield Village as Grimm Jewelry Store.

We’ve just digitized dozens of photographs from our collections related to the building, including this 1926 interior photo showing Engelbert Grimm hard at work. Visit our Digital Collections to see all of the Grimm Jewelry images.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village

Henry Ford and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Concert in the Ford Symphony Gardens, Century of Progress International Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, 1934. THF212561

For the past 24 years the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and The Henry Ford have teamed up for Salute to America, our annual concert and fireworks celebration in Greenfield Village. But the affiliation between the DSO and our organization goes back much farther than that.

Preparing for a Performance in Ford Symphony Gardens, Century of Progress International Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, 1934. THF212547

The connection dates back to the 1934 Chicago World's Fair, A Century of Progress International Exposition. Ford Motor Company’s exhibits were housed in the famous Rotunda building and also included the Magic Skyway and the Ford Symphony Gardens. The large amphitheater of the Symphony Gardens hosted several musical and stage acts, including the DSO, who Ford sponsored for 150 concerts over the course of the year. The symphonic notes proved so popular that Henry and Edsel Ford decided to launch a radio program featuring selections from symphonies and operas - the Ford Sunday Evening Hour. The weekly program played to over 10,000,000 listeners each broadcast over the CBS network (the same network that now presents The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation). Musical pieces were played by DSO musicians under the name Ford Symphony Orchestra, a 75-piece ensemble, and were conducted by Victor Kolar, the DSO’s associate director, for the first few years of the show. Pieces ranged from symphony classics including works by Handel, Strauss, Liszt, Wagner, Handel, Puccini, Bizet, and Tchaikovsky (including, of course, the 1812 Overture), to some of Henry Ford’s favorite traditional and folk songs like Turkey in the Straw and Annie Laurie, and even included popular tunes such as Night and Day by Cole Porter.

Each broadcast featured guest stars, soloists, and singers such as Jascha Heifetz, Grisha Goluboff, Gladys Swarthout, Grete Stükgold, and José Iturbi. The broadcast performances were open to the public for free, first at Orchestra Hall from 1934-1936, and then at the Masonic Temple 1936-1942. The show ran from 1934-1942, September-May with 1,300,000 live attendees and countless radio listeners tuning in.

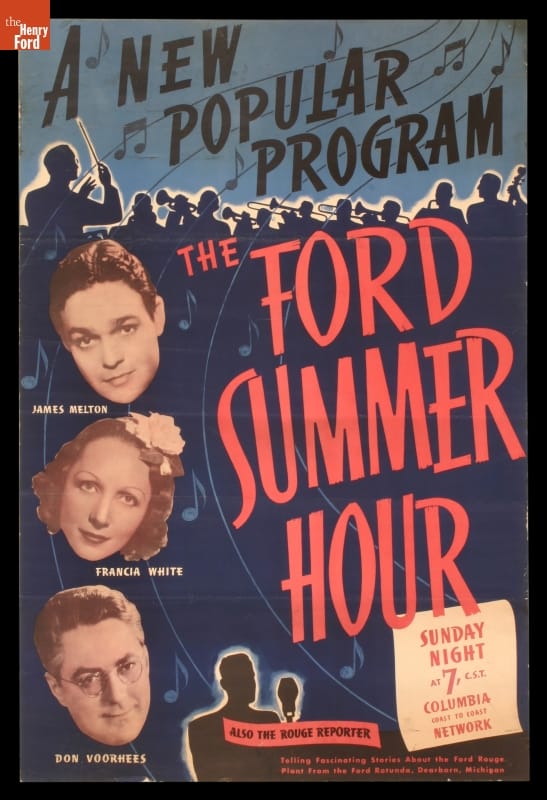

Advertising Poster, The Ford Summer Hour, 1939. THF111542

Salute to America is our summer music tradition, and listeners in 1939 must have wanted some summer-themed music as well because Henry and Edsel started the Ford Summer Hour that year. Like the winter program, it was broadcast each Sunday evening on CBS, from May to September and featured a smaller 32-piece orchestra, again mostly made up of DSO musicians. Guest stars and conductors appeared, such as Don Voorhees, James Melton, and Jessica Dragonette.

The show included music from Ford employee bands like the River Rouge Ramblers, Champion Pipe Band, and the Dixie Eight. This was a program of lighter music, popular songs, and tunes from musical comedies and operettas. Apparently not everyone appreciated the lighter fare; a letter from a concerned listener stated:

“...as the strains of the trivial program of Ford Summer Show float into my room, I am moved to contrast them with the fine programs of your winter series, and to wonder why the myth persists that in hot weather the human mentality is unequal to the strain of listening to good music. Pardon me while I switch my radio to station WQXR which has fine music the year round.”

Strong words from the listening public, though apparently not the majority as the summer program rivaled the winter program with about 9,000,000 listeners per broadcast. The Ford Summer Hour, broadcast from the Ford Rotunda, only ran three seasons, but played a wide range of music for listeners such as Heigh Ho from Snow White, Dodging a Divorcee, selections from Carmen, Oh Dear, What Can the Matter Be, and One Fine Day from Madame Butterfly.

Both programs ceased by 1942 with the opening of World War II. Henry Ford II tried to bring back the Ford Sunday Evening Hour in 1945, broadcasting the same type of music by DSO musicians, but times and tastes had changed and the program was discounted after the first season.

Kathy Makas is a Benson Ford Research Center Reference Archivist at The Henry Ford. To learn more about the Ford Sunday Evening Hour or Ford Summer Hour, visit the Benson Ford Research Center or email your questions to us here.

Greenfield Village, events, Salute to America, by Kathy Makas, Ford Motor Company, Edsel Ford, Ford family, radio, world's fairs, Michigan, Henry Ford, music, Detroit

Garage Art

Photo by Bill Bowen.

Model T mechanics are restoration artists in their own right.

The Henry Ford has a fleet of 14 Ford Model T’s, 12 of which ride thousands of visitors along the streets of Greenfield Village every year.

With each ride, a door slams, shoes skid across the floorboards, seats are bounced on, gears are shifted, tires meet road, pedals are pushed, handles are pulled and so on. Makes maintaining the cars and preserving the visitor experience a continuous challenge.

“These cars get very harsh use,” said Ken Kennedy, antique vehicle mechanic and T Shed specialist at The Henry Ford. “Between 150,000 and 180,000 people a year ride in them. Each car gives a ride every five to seven minutes, with the longest route just short of a mile. This happens for nine months a year.”

The T Shed is the 3,600-square-foot garage on the grounds of Greenfield Village where repairs, restoration and maintenance magic happen. Kennedy, who holds a degree in restoration from McPherson College in Kansas, leads the shed’s team of staff and volunteers — many car-restoration hobbyists just like him.

“I basically turned my hobby into a career,” quipped Kennedy, who began restoring cars long before college. His first project: a 1926 two-door Model T sedan. “I also have a 1916 Touring and a 1927 Willys-Knight. And I’m working on a Model TT truck,” he added.

April through December, the shed is humming, doing routine maintenance and repairs on the Model T’s as well as a few Model AA trucks that round out Greenfield Village’s working fleet. “What the public does to these cars would make any hobbyist pull their hair out. Doors opening and shutting with each ride. Kids sliding across the seats wearing on the upholstery,” said Kennedy. Vehicles often go through a set of tires every year. Most hobbyist-owned Model T’s have the same set for three-plus decades.

With the heavy toll taken on the vehicles, the T Shed’s staff often makes small, yet important, mechanical changes to the cars to ensure they can keep up. “We have some subtle things we can do to make them work better for our purpose,” said Kennedy. Gear ratios, for example, are adjusted since the cars run slow — the speed limit in Greenfield Village is 15 miles per hour, maximum. “The cars look right for the period, but these are the things we can do to make our lives easier.”

In the off-season, when Greenfield Village is closed, the T Shedders shift toward more heavy mechanical work, replacing upholstery tops and fenders, and tearing down and rebuilding engines. While Kennedy may downplay the restoration, even the conservation, underpinnings of the work happening in the shed, the mindset and philosophy are certainly ever present.

“Most of the time we’re not really restoring, but you still have to keep in mind authenticity and what should be,” he said. “It’s not just about what will work. You have to keep the correctness. We can do some things that aren’t seen, where you can adjust. But where it’s visible, we have to maintain what’s period correct. We want to keep the engines sounding right, looking right.”

Photo by Bill Bowen.

RESTORATION IN THE ROUND

Tom Fisher, Greenfield Village’s chief mechanical officer, has been restoring and maintaining The Henry Ford’s steam locomotives since 1988. “It was a temporary fill-in; I thought I’d try it,” Fisher said of joining The Henry Ford team 28 years ago while earning an engineering degree.

He now oversees a staff with similarly circuitous routes — some with degrees in history, some in engineering, some with no degree at all. Most can both engineer a steam-engine train and repair one on-site in Greenfield Village’s roundhouse.

“As a group, we’re very well rounded,” said Fisher. “One of the guys is a genius with gas engines — our switcher has a gas engine, so I was happy to get him. One guy is good with air brake systems. We feel them out, see where they’re good and then push them toward that.”

Fisher’s team’s most significant restoration effort: the Detroit & Lima Northern No. 7. Henry Ford’s personal favorite, this locomotive was formerly in Henry Ford Museum and took nearly 20 years to get back on the track.

“We had to put on our ‘way-back’ hats and say this is what we think they would have done,” said Fisher.

No. 7 is one of three steam locomotives running in Greenfield Village. As with the Model T’s, maintaining these machines is a balance between preserving historical integrity and modernizing out of necessity.

“A steam locomotive is constantly trying to destroy itself,” Fisher said. “It wears its parts all out in the open. The daily firing of the boiler induces stresses into the metal. There’s a constant renewal of parts.”

Parts that Fisher and his team painstakingly fabricate, cast and fit with their sturdy hands right at the roundhouse.

DID YOU KNOW?

The No. 7 locomotive began operation in Greenfield Village to help commemorate Henry Ford’s 150th birthday in 2013.

Additional Readings:

- Ingersoll-Rand Number 90 Diesel-Electric Locomotive, 1926

- Keeping the Roundhouse Running

- Model Train Layout: Demonstration

- Part Two: Number 7 is On Track

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, trains, The Henry Ford Magazine, railroads, Model Ts, Greenfield Village, Ford Motor Company, engineering, collections care, cars, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford