Posts Tagged henry ford

Sidney Houghton: The Fair Lane Rail Car and the Engineering Laboratory Offices

In my last blog post, I discussed how Sidney Houghton (1872–1950), a British interior designer and interior architect, met and befriended Henry Ford during World War I and, following the war, became part of the Fords’ inner circle.

The Benson Ford Research Center at The Henry Ford holds significant correspondence, designs, and records relating to commissions between Houghton and Henry and Clara Ford. Probably the single document that details the variety of Ford commissions associated with Houghton is a brochure, more of a portfolio of projects, published by Houghton in the early 1930s, to promote his design firm.

Cover of Houghton brochure. / THF121214

From Houghton’s reference images, we can document many commissions that no longer survive, as well as provide background for some that are still do. This post centers on two projects, the Fair Lane rail car and Henry and Edsel Ford’s offices in the Ford Engineering Laboratory, which still exist. Fortunately, aspects of both still exist in The Henry Ford’s collection!

The Fair Lane Rail Car

The Fair Lane rail car. / THF80274

Edsel and Eleanor Ford, Henry and Clara Ford, and Mina and Thomas Edison pose on the car’s rear platform about 1923. / THF97966

Images of the Fair Lane rail car from Houghton brochure. / THF121225a

The Fair Lane rail car was built by the Pullman Rail Car Company in Pullman, Illinois, and delivered to Henry and Clara Ford in Dearborn, Michigan, in summer 1921. A detailed history and background on the rail car by Matt Anderson, The Henry Ford’s Curator of Transportation, can be found here.

Sidney Houghton was responsible for creating the interiors and furnishings for the car. Many sources state that he worked with Clara Ford on the designs. What is likely is that Clara Ford approved or disapproved of Houghton’s design work. This is especially evident in the public rooms of the rail car—what Houghton called the “dining saloon” and the “observation parlour.”

Dining saloon in 1921. / THF148009

The same view in 2021. / THF186285

Glassware storage. / THF186283

The dining room walls are paneled in dark walnut, with veneered elements of mahogany. The effect suggests a richly appointed room from which to view the passing scenery. The styles that Houghton employed, and Clara Ford approved, derived from a combination of eighteenth-century English classical styles, including the caned and oval-backed side chairs and the elegantly carved three-quarter relief columns around the walls. China and glassware were stored in built-in units fitted with slots or pegs to keep the objects from shifting during travel.

The observation saloon in 1921. / THF148015

The observation saloon in 1921. / THF148012

The observation saloon in 2021. / THF186264

Detail of the observation saloon. / THF186263

What Houghton called the “observation saloon” was where passengers would spend their days while traveling. It was fitted out with sets of upholstered armchairs below the windows and a slant front desk and bookcase against the inner wall. This was an extremely useful piece of furniture; while at the desk, you could read or write correspondence, and when done, store your letters in one of the many drawers in the desk. The upper case allowed plenty of room to store books and other reading materials. Dials above the door to the observation platform displayed the miles per hour, the time, and the outdoor temperature.

As you can see in the recent photographs, over time the painted woodwork in this room was stripped and refinished. Also, the wonderful slant front desk and original light fixtures have not survived. Fortunately, after the Fords sold the rail car in 1942, a subsequent owner lovingly restored the interior, including reproducing much of the furniture, before donating it to The Henry Ford.

The Ford Engineering Laboratory Offices

In the early 1920s, Henry Ford commissioned his favorite architect, Albert Kahn, to design what Ford called his Engineering Laboratory in Dearborn. Completed in 1923, this building came to be the heart of the Ford Motor Company enterprise. Both Henry and his son, Edsel, had offices in the building, and Henry commissioned Sidney Houghton to design identical furniture and woodwork for each. Both offices survive, as does most of the furniture, which is now in the collections of The Henry Ford. Of all of Houghton’s projects for the Fords, it is the best preserved.

Henry Ford’s office in 1923. / THF237704

Henry Ford’s office in 1923. / THF237702

Edsel Ford’s office (top) and Henry Ford’s office (bottom) from Houghton brochure. / THF121221a

In looking at the offices, one thing comes to mind: they were designed to impress. Like the rail car, they are paneled in rich walnut, with matching walnut furniture. Both have large conference tables; Henry’s is round, while Edsel’s is rectangular.

Conference table used in Edsel Ford’s office. / THF158754

The chairs and tables all feature heavy, turned, and curved legs, known as cabriole legs. They are also inlaid with woods with their grains carefully arranged to their fullest and most luxurious effect.

Desk chair. / THF158365

Armchair. / THF158349

Easy chair. / THF158367

Sofa. / THF158750

The style of this furniture is English Jacobean, deriving from forms used in the seventeenth century. The intent with this furniture was to show off wealth and good taste—as befit a person of Henry Ford’s status.

Console table. / THF158371

This console table, seen in the photograph behind Henry Ford’s desk, is inlaid with matched veneers along the drawer front and handles in the shapes of shells. The elaborately turned legs, which look like upside down trumpets, are characteristic of the Jacobean style in England. Combined with the cabriole legs on the chairs, Houghton has mixed and matched English furniture styles here in what decorative arts historians call an eclectic fashion.

Tall Case Clock, works by Waltham Clock Company. / THF158743

If the rest of the office furniture was meant to impress, the tall case clock takes it over the top. Henry Ford was known for his love of clocks and watches. This piece was undoubtedly something that he was proud to possess and show off to guests in his office.

We know from documents that Henry Ford rarely used his office. He preferred to be out in the field visiting with employees or, in later years, in Greenfield Village. Consequently, the furniture shows little signs of wear. Further, there are few photographs of Henry Ford in his office, other than those taken in 1923 when it was newly installed.

Henry Ford’s office in 1949. / THF149868

Taken two years after Henry Ford’s death in 1947, this image shows how he used the office.

Henry Ford by Edward Pennoyer, 1931. / THF174088

On the wall behind the desk is a painting by artist Edward Pennoyer, used as an illustration for a 1931 advertisement. Henry Ford undoubtedly liked the image of himself with the Quadricycle, his first automobile, and hung it behind his desk.

Photograph of Henry Ford with Lord Halifax, to Henry Ford’s right, surrounded by unknown figures, November 1941. / THF240734

Henry Ford with Lord Halifax, November 1941. / THF241506

Henry Ford with Lord Halifax, November 1941. / THF241508

Only three photographs survive of Henry Ford in his office. All date to November 1941, when the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, visited Henry Ford and toured the Rouge Factory. Guests to the Engineering Laboratory were almost always photographed outside the building or in the adjacent Henry Ford Museum or Greenfield Village.

The third photograph above shows another work of art in the office. The landscape shows Henry Ford’s Wayside Inn, in South Sudbury, Massachusetts, purchased in 1923. This, of course, was a place near and dear to Henry Ford, and helped him to realize his goal of creating Greenfield Village.

As we can see, Sidney Houghton was close to Henry and Clara Ford, designing Henry’s office and the Fair Lane rail car intimate environment, used on a very regular basis. In the next blog post, I will look at the most intimate of the Fords’ interiors—their Fair Lane Estate, onto which Houghton put his own influence during the first half of the 1920s.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- The Webster Dining Room Reimagined: An Informal Family Dinner

Fully Furnished - Designs for Aging: New Takes on Old Forms

- The Enigmatic Sidney Houghton, Designer to Henry and Clara Ford

decorative arts, Sidney Houghton, railroads, Michigan, Henry Ford, furnishings, Ford Motor Company, Fair Lane railcar, Edsel Ford, design, Dearborn, by Charles Sable

Henry Ford's “Sweepstakes” Celebrates its 120th Anniversary

The original “Sweepstakes,” on exhibit in Driven to Win: Racing in America in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Auto companies often justify their participation in auto racing by quoting the slogan, “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday.” When Henry Ford raced in “Sweepstakes,” it was a case of win on Sunday to start another company on Monday. On October 10, 2021, we commemorate the 120th anniversary of the race that changed Ford’s life—and ultimately changed the course of American automotive history.

In the summer of 1901, things were not going well for Henry. His first car company, the Detroit Automobile Company, had failed, and his financial backers had doubts about his talents as an engineer and as a businessman. Building a successful race car would reestablish his credibility.

Ford didn’t work alone. His principal designer was Oliver Barthel. Ed “Spider” Huff worked on the electrical system, Ed Verlinden and George Wettrick did the lathe work, and Charlie Mitchell shaped metal at the blacksmith forge. The car they produced was advanced for its day. The induction system was a rudimentary form of mechanical fuel injection, patented by Ford, while the spark plugs may have been the first anywhere to use porcelain insulators. Ford had the insulators made by a Detroit dentist.

1901 Ford "Sweepstakes" Race Car. / THF90168

The engine had only two cylinders, but they were huge: bore and stroke were seven inches each. That works out to a displacement of 538 cubic inches; horsepower was estimated at 26. Ford and Barthel claimed the car reached 72 miles per hour during its road tests. That doesn’t sound impressive today, but in 1901, the official world speed record for automobiles was 65.79 miles per hour.

Ford entered the car in a race that took place on October 10, 1901, at a horse racing track in Grosse Pointe, Michigan. The race was known as a sweepstakes, so “Sweepstakes” was the name that Ford and Barthel gave their car. Henry’s opponent in the race was Alexander Winton, who was already a successful auto manufacturer and the country’s best-known race driver. No one gave the inexperienced, unknown Ford a chance.

When the race began, Ford fell behind immediately, trailing by as much as 300 yards. But Henry improved his driving technique quickly, gradually cutting into Winton’s lead. Then Winton’s car developed mechanical trouble, and Ford swept past him on the main straightaway, as the crowd roared its approval.

Henry Ford behind the wheel of his first race car, the 1901 "Sweepstakes" racer, on West Grand Boulevard in Detroit, with Ed "Spider" Huff kneeling on the running board. / THF116246

Henry’s wife, Clara, described the scene in a letter to her brother: “The people went wild. One man threw his hat up and when it came down he stamped on it. Another man had to hit his wife on the head to keep her from going off the handle. She stood up in her seat ... screamed ‘I’d bet $50 on Ford if I had it.’”

Henry Ford’s victory had the desired effect. New investors backed Ford in his next venture, the Henry Ford Company. Yet he was not home free. He disagreed with his financiers, left the company in 1902, and finally formed his lasting enterprise, Ford Motor Company, in 1903.

Ford sold “Sweepstakes” in May of 1902, but eventually bought it back in the 1930s. He had a new body built to replace the original, which had been damaged in a fire, and he displayed the historic vehicle in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. Unfortunately, Ford did not keep good records of his restoration, and over time, museum staff came to believe that the car was not an original, but a replica. It was not until the approach of the 1901 race’s 100th anniversary that the car was closely examined and its originality verified. Using “Sweepstakes” as a pattern, Ford Motor Company built two running replicas to commemorate the centennial of its racing program in 2001.

Ford gifted one of the replicas to us in 2008. That car is a regular feature at our annual Old Car Festival in September. Occasionally, it comes out for other special activities. We recently celebrated the 120th anniversary of the 1901 race by taking the replica to the inaugural American Speed Festival at the M1 Concourse in Pontiac, Michigan. The car put on a great show, and it even won another victory when it was awarded the M1 Concourse Prize as a festival favorite.

The “Sweepstakes” replica caught the attention of Speed Sport TV pit reporter Hannah Lopa at the 2021 American Speed Festival. / Photo courtesy Matt Anderson

The original car, one of the world’s oldest surviving race cars, is proudly on display at the entrance to our exhibit Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors. You can read more about how we developed that display in this blog post.

Specifications |

| Frame: Ash wood, reinforced with steel plates Wheelbase: 96 inches |

Bob Casey is Former Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. This post was adapted from our former online series “Pic of the Month,” with additional content by Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Driven to Win: Sports Car Performance Center

- Barney Oldfield: America’s Racer

- Fast Cars and Warm Quilts: Auto Racing’s "Quilt Lady"

- 2016 Ford GT Full-Size Clay Model, 2014

20th century, 1900s, 21st century, 2020s, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Michigan, making, Henry Ford Museum, Henry Ford, Driven to Win, design, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson, by Bob Casey, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Sidney Houghton is one of the most interesting and yet-to-be-documented figures in the group surrounding Henry and Clara Ford. Many in the Fords’ entourage are colorful and well-researched, including Harry Bennett, Henry’s security chief, known as the notorious head of the Ford Motor Company “Service” Department; Henry’s business manager, Ernest Liebold, who handled all financial transactions; and even their son, Edsel Ford, whose life and important cultural contributions are thoroughly documented. The great Ford historian Ford R. Bryan tells the story of these figures in his book, Henry’s Lieutenants (1993). Bryan frequently mentions Sidney Houghton, most notably in his book Friends, Family, and Forays (2002).

Perhaps Houghton remains undocumented because he was British, and in the decades before Internet resources became widely available, American researchers like Bryan had limited access to British sources. Today, we are fortunate to not only have the profound resources of the Benson Ford Research Center at The Henry Ford at our disposal, but also digital access to repositories around the world. As Curator of Decorative Arts, I have spent considerable time trying to fully grasp the enigmatic Mr. Houghton—his biography, his business, and, most importantly, his relationship with Henry and Clara Ford. This blog is the first in a series that will delve into this mostly hidden story.

Now, you may ask, why should we care about the Fords’ interior designer? Seeing and understanding the interior environments that the Fords created to live and work provides us with great insight into their characters, creating a well-rounded picture of their lives. We can understand their motivations and desires and see how these changed over time. We can peel back the larger-than-life personas of the Fords that come with such public lives and see them as individuals.

What Do We Know About Sidney Houghton’s Early Life?

Researching Houghton was not easy. The first place I looked was Ancestry.com, but Houghton is a very common name in Britain. After a lot of digging and working with colleagues at The Henry Ford, I located Sidney Charles Houghton, who was born in 1872 and died in 1950. He was the son of cabinetmaker Charles Houghton, which likely led to his interest in furniture-making and interior design.

One of the questions still in my mind is: Where was Houghton educated? To date, I have not been able to find out which art school he attended—these records do not appear to be available online. What I do know is that he married in 1895, and had a family consisting of two sons by 1898. By 1910, according to the British census, his business, Houghton Studio, was established in London.

Houghton in World War I

From Ford R. Bryan’s publications and resources in the Benson Ford Research Center, I knew that Houghton was in the British Navy during World War I. I searched the British National Archives and found his fascinating military service record. Houghton, I discovered, was an experienced yachtsman, and was commissioned as a commander. He helped to create patrol boats, called P-boats, that swiftly located enemy submarines. In 1917, he was sent to the United States to work with Reginald Fessenden (1866–1932), a Canadian-American inventor who worked in early radio. Together, they developed an early sonar system to locate enemy ships, submarines, and mines. For his contributions to the war effort, Houghton was awarded the Order of the British Empire, or O.B.E., in 1919.

Through the reminiscences of Ernest Liebold, held in the Benson Ford Research Center, I discovered that Houghton was brought into the Ford Motor Company’s war effort to create what Liebold called the Eagle boats. These were similar to the British P-boats. Unlike the relatively simple P-boats, though, the Eagle boats would be like a “young battleship,” according to Liebold. He went on to state that the boats would “have the eye of an eagle and would flit over the seas.”

Eagle Boat #1 on Launching Trestle at the Ford Rouge Plant, July 11, 1918. / THF270275

Eagle Boat #60 Lowered to Water, August 1919. / THF270277

Liebold continued:

Houghton came along, and he said, “We ought to have a listening device put on those ships to detect submarines.” That is where [Thomas] Edison came in to develop this listening device, and I think Houghton is the man who contacted him. I remember him coming out with a long rod and stuff, and it was so darned secret that nobody knew a thing about it.

They had a special room provided for it in the Eagle boats. It was to be this listening chamber in which the apparatus was placed. They could detect a submarine by the beat of its propellers. A magnetic signal could determine just exactly in what direction it was, [sic] and approximately, from the intensity of the sound of the beating of the propeller, they could tell just what distance and in what direction it was.

They would radio that information to the nearest battleship in a cordon of battleships, or destroyers or whatever they had. They would be able to attack the submarine, you see. That was the object of it.

As an integral member of the Eagle boat team, it is highly likely that Houghton travelled to Dearborn and met Henry Ford. We know from later correspondence that Henry and Clara developed an abiding personal friendship with Houghton which continued through the 1920s. They commissioned a series of projects, beginning with the Fords’ yacht, the Sialia—but I am getting ahead of myself. At this point, I would like to discuss Houghton’s work in interior design, specifically his role as an interior architect.

Sidney Houghton’s Studio

Cover of Houghton’s Studio Catalogue, circa 1928. / THF121214

Back Cover of Houghton’s Studio Catalogue, circa 1928. / THF121230

This brochure or trade catalogue gives us great insight into the Houghton Studio. We date it to the late 1920s, when the projects Houghton worked on for the Fords were complete. From the text, we can see just what the firm’s capabilities were. The back cover reads: “Designs and estimates for decoration and furnishing of every kind / from the simplest to the most exotic / always in good style / always at exceptional values.” What this tells us is that Houghton Studio was a rarity in the interior design world.

Houghton was an interior architect, meaning that he designed both interiors and furnishings—the woodwork, wall treatments, lighting, furniture, textiles, and accessories—to create a unified interior environment. In new construction, an interior architect would collaborate with the architect to create an interior in harmony with the architecture. This contrasts with our present-day conception of an interior designer as a person who simply selects existing furnishings that harmonize to create a unified interior aesthetic. Obviously, Houghton Studio’s clients were wealthy and able to afford the best.

Chateau Laurier National Hotel, Ottawa Canada. / THF121219a

Designs for Modern Furniture. / THF121226a

Like most of his contemporaries, Houghton worked in a variety of styles, as demonstrated in the images above—from period revivals as seen in the Chateau Laurier National Hotel, in Ottawa, Canada, to his renderings for “Modern” furniture, done in what we would describe as the Art Deco style, which was synonymous with high-end 1920s taste.

List of Commissions in the Houghton Catalogue. / THF121229b

One of the most interesting pages in the catalogue notes several commissions to design interiors for yachts, which was a specialty of the Houghton Studio. The most important of these was a commission for the Sialia, Henry Ford’s yacht. The Fords purchased the yacht just before World War I, and it was requisitioned for use by the U.S. Navy in 1917. The ship was returned to Henry Ford in 1920. At this point, Sidney Houghton was asked to redesign the interiors.

Henry Ford’s Sialia

Henry Ford’s Yacht, Sialia, Docked at Ford Rouge Plant, Dearborn, Michigan, 1927. /THF140396

According to Ford R. Bryan, the cost of the interiors was approximately $150,000. As seen here, the interiors are comfortable, but relatively simple. During the 1920s, the Fords occasionally used the Sialia, but Henry and Clara Ford preferred other means of travel, usually by large Ford corporate ore carriers, when they traveled to their summer home in Michigan’s upper peninsula. According to the ship’s captain, Perry Stakes, Henry Ford never really liked the Sialia, and he sold it in July of 1927.

Parlor on Sialia, Henry Ford’s Yacht, circa 1925. / THF92100

Bedroom on Sialia, Henry Ford’s Yacht, circa 1925. / THF92098

Following the Sialia commission, the Fords found a kindred spirit in Houghton. The archives contain ample correspondence from the early 1920s, with the Fords asking Houghton to return to Dearborn. Houghton subsequently received a commission to design the interior of the Fords’ Fair Lane railroad car in 1920. Between 1920 and 1926, Houghton was deluged with projects from the Fords, including the redesign of the Fair Lane Estate interiors, design of Henry and Edsel’s offices in the new Ford Engineering Laboratory, interiors for the Dearborn Country Club, as well as interiors for the Henry Ford Hospital addition.

In the next post in this series, we will look closer at several of these projects and present surviving renderings from the Fair Lane remodeling, as well as furniture from the Engineering Laboratory offices.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Additional Readings:

- Sidney Houghton: The Fair Lane Estate

- Striker to the Line: An English Plate Depicting an American Sport

- Marshmallow Love Seat, 1956-1965

- Court Cupboard, Owned by Hannah Barnard, 1710-1720

Sidney Houghton, World War I, technology, research, home life, Henry Ford, furnishings, Ford Motor Company, design, decorative arts, by Charles Sable, archives

There’s Only One Greenfield Village

Greenfield Village map, 1951. / THF133294

Greenfield Village map, 1951. / THF133294

Greenfield Village may just look like a lot of buildings to some, but each building tells stories of people. When I wrote The Henry Ford Official Guidebook, it really hit me how unique and one-of-a-kind Greenfield Village is. I wanted to share several stories I found particularly interesting about Greenfield Village.

Researching Building Stories

Whenever we research a Village building, we usually start with archival material—looking at sources like census records, account books, store invoices (like the one below, related to Dr. Howard’s Office), and old photographs—to give us authentic accounts about our subjects’ lives. Here are some examples.

1881 invoice for Dr. Howard. / THF620460

At Daggett Farmhouse, Samuel Daggett’s account book showed that he not only built houses but also dug stones for the community schoolhouse; made shingles for local people’s houses; made chairs, spinning wheels, coffins, and sleds; and even pulled teeth! If you are interested in learning more about how our research influenced the interpretation at Daggett, along with four other Village buildings, check out this blog post.

Daggett Farmhouse, photographed by Michelle Andonian. / THF54173

For Dr. Howard’s Office, we looked at old photographs, family reminiscences, the doctor’s daily record of patients and what he prescribed for them, his handwritten receipt (recipe) book of remedies, and invoices of supplies and dried herbs he purchased. You can read more about the history of Dr. Alonson Howard and his office in this blog post.

Page from Dr. Howard’s receipt book. / THF620470

For J.R. Jones General Store, we used a range of primary sources, from local census records to photographs of the building on its original site (like the one below) to account books documenting purchases of store stock from similar general stores. You can read more about the history of J.R. Jones General Store in this blog post.

Photo of J.R. Jones General Store on its original site. / THF255033

Urbanization and Industrialization Seen through Greenfield Village Buildings

Many Greenfield Village buildings were acquired because of Henry Ford’s interests. But some give us the opportunity to look at larger trends in American life, especially related to urbanization and industrialization.

Engelbert Grimm sold clocks and watches to Detroit-area customers, including Henry Ford, in the 1880s. But Grimm Jewelry Store also demonstrates that in an increasingly urban and industrial nation, people were expected to know the time and be on time—all the time.

Grimm Jewelry Store in Greenfield Village. / THF1947

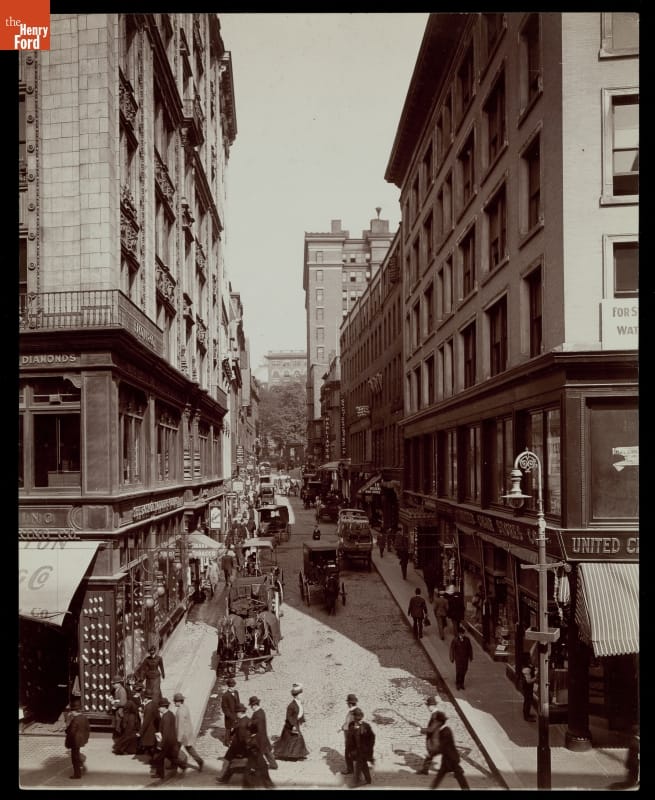

Related to this, notice the public clock in the Detroit Publishing Company photograph below of West 23rd Street, New York City, about 1908. (Clue: Look down the street, above the horse-drawn carriage, and you’ll see a large street clock on a stand.) You can read more about the emergence of “clock time” in this blog post.

THF204886

Smiths Creek Depot is here because of its connection with Thomas Edison. But this building also shows us that railroad depots at the time were more than simply the place to catch a train—they were also bustling places where townspeople connected with the outside world. Below you can see a photo of Smiths Creek in Greenfield Village, as well asthe hustle and bustle of railroad depots in a wonderful image of the Union Pacific Depot in Cheyenne, Wyoming, from about 1910.

Smiths Creek Depot in Greenfield Village. / THF1873

Union Pacific Depot. / THF204972

Henry Ford brought Sarah Jordan Boarding House to Greenfield Village because it was home to many of Thomas Edison’s workers. It was also one of three residences wired for Edison’s new electrical lighting system in December 1879—and it is the only one still in existence. In the bigger picture, the mushrooming of boarding houses at this time was particularly due to a shortage of affordable housing in the growing urban-industrial centers, which were experiencing a tremendous influx of new wage laborers.

Sarah Jordan Boarding House in Greenfield Village. / THF2007

Sarah Jordan Boarding House on its original site in Menlo Park, New Jersey, in 1879. / THF117242

Luther Burbank and Henry Ford

Other buildings in Greenfield Village have strong ties to Henry’s personal relationships. Henry Ford met horticulturalist Luther Burbank in connection with the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. That year, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and a few other companions traveled there to attend Edison Day. Luther Burbank welcomed them to the area.

Panama-Pacific International Exposition Souvenir Medal. / THF154006

Afterward, the group followed Burbank up on an invitation to visit him at his experimental garden in Santa Rosa, California. Edison and Ford had a grand time there. Burbank later wrote, “The ladies said we acted like three schoolboys, but we didn’t care.”

Thomas Edison, Luther Burbank, and Henry Ford at Burbank's home in Santa Rosa, California. / THF126337

After that visit, the original group, plus tire magnate Harvey Firestone, drove by automobile to the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego. During that trip, Edison proposed a camping trip for Ford, Firestone, and himself. The Vagabonds camping trips, taking place over the next nine years, were born!

“Vagabonds” camping trip. / THF117234

Henry Ford was so inspired by Luther Burbank’s character, accomplishments, and “learning by doing” approach that he brought to Greenfield Village a modified version of the Luther Burbank Birthplace and a restored version of the Luther Burbank Garden Office from Santa Rosa.

Luther Burbank Garden Office in Greenfield Village. / THF1887

Greenfield Village Buildings and World’s Fair Connections

Greenfield Village has several other direct connections to World’s Fairs of the 1930s. At Chicago’s Century of Progress Exposition of 1933–1934, for example, an “industrialized American barn” with soybean exhibits later became the William Ford Barn in Greenfield Village.

THF222009

In a striking Albert Kahn–designed building, Ford Motor Company boasted the largest and most expensive corporate pavilion of the same Chicago fair. It drew some 75% of visitors to the fair that year. After the fair, the central part of this building was transported from Chicago to Dearborn, where it became the Ford Rotunda. It was used as a hospitality center until it burned in a devastating fire in 1962.

Ford at the Fair Brochure, showing the building section that would eventually become the Ford Rotunda. / THF210966

Ford Rotunda in Dearborn after a 1953 renovation. / THF142018

At the Texas Centennial Exposition in 1936, a model soybean oil extractor was demonstrated. This imposing object is now prominently displayed in the Soybean Lab Agricultural Gallery in Greenfield Village.

A presenter at the Texas Centennial Exposition demonstrates how the soybean oil extraction process works with a model of a soybean oil extractor that now resides in the Soybean Lab in Greenfield Village. / THF222337

At the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Henry Ford promoted his experimental school system in a 1/3-scale version of Thomas Edison’s Menlo Park Machine Shop in Greenfield Village. Students made model machine parts and demonstrated the use of the machines.

Boys from Henry Ford's Edison Institute Schools operate miniature machine replicas in a scale model of the Menlo Park Machine Shop during the 1939-40 New York World's Fair. / THF250326

Village Buildings That Influenced Famous Men

Several people whose stories are represented in Greenfield Village were influenced by the places in which they grew up and worked, like the Wright Brothers, shown below on the porch of their Dayton, Ohio, home, now the Wright Home in the Village, around 1910.

THF123601

In addition to practicing law in Springfield, Illinois, Abraham Lincoln traveled to courthouses like the Logan County Courthouse in Greenfield Village to try court cases for local folk. The experiences he gained in these prepared him for his future role as U.S. president (read more about this in this “What If” story).

THF110836

Enterprising young Tom Edison took a job as a newsboy on a local railway, where one of the stops was Smiths Creek Station. This and other experiences on that railway contributed to the man Thomas Edison would become—curious, entrepreneurial, interested in new technologies, and collaborative.

Young Thomas Edison as a newsboy and candy butcher. / THF116798

Henry Ford, the eldest of six children, was born and raised in the farmhouse pictured below, now known as Ford Home in Greenfield Village. Henry hated the drudgery of farm work. He spent his entire life trying to ease farmers’ burdens and make their lives easier.

THF1938

Henry J. Heinz

Henry J. Heinz (the namesake of Heinz House in Greenfield Village) wasn’t just an inventor or an entrepreneur or a marketing genius: he was all of these things. Throughout the course of his career, he truly changed the way we eat and the way we think about what we eat.

H.J. Heinz, 1899. / THF291536

Beginning with horseradish, Heinz expanded his business to include many relishes and pickles—stressing their purity and high quality at a time when other processed foods did not share these characteristics. The sample display case below highlights the phrase “pure food products.”

Heinz Sample Display Case. / THF174348

Heinz had an eye for promotion and advertising unequaled among his competitors. This included signs, billboards, special exhibits, and, as shown below, the specially constructed Heinz Ocean Pier, in Atlantic City, New Jersey, which opened in 1898.

Advertising process photograph showing Heinz Ocean Pier. / THF117096

The pickle pin, for instance, was a wildly successful advertising promotion. Heinz first offered a free pickle-shaped watch fob at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. At some point, a pin replaced the watch fob, and the rest is history!

Heinz Pickle Pin "Heinz Homestyle Soups." / THF158839

By the time of H.J. Heinz’s death in 1919, his company had grown into one of the largest food processing businesses in the nation. His company was known for its innovative food processing, packaging, advertising, and enlightened business practices. You can learn more about Heinz House and its journey to Greenfield Village here.

Even More Fun Facts about Greenfield Village Buildings

Most of the time, we focus on big themes that tell American history in relatable ways. When we choose a theme to focus on, we inevitably leave out interesting little-known facts. For example, Cohen Millinery was a dry goods store, a candy store, a Kroger grocery, and a restaurant during its lifetime!

Cohen Millinery at its original site. / THF243213

Surprisingly, for most of its life prior to its incorporation into Greenfield Village, Logan County Courthouse was a private residence. Many different families had lived there, including Mr. and Mrs. Elijah Watkins, the last caretakers before Henry Ford acquired the building. They are depicted below, along with an interior shot of one of their rooms when Henry Ford’s agents went to look at the building.

Mr. and Mrs. Watkins. / THF238624

Interior of Logan County Courthouse at its original site. / THF238596

In the 1820s, eastern Ohio farmers realized huge profits from the fine-grade wool of purebred Merino sheep. But by the 1880s, competition had made raising Merino sheep unprofitable. Benjamin Firestone, the previous owner of Firestone Farmhouse and father of Harvey Firestone, however, stuck with the tried and true. Today, you can visit our wrinkly friends grazing one of several pastures in the Village.

Merino sheep at Firestone Farm in Greenfield Village in 2014. / THF119103

We have several different breeds of animals at the Village, but some of our most memorable were built, not bred. The Herschell-Spillman Carousel is a favorite amongst visitors. Many people think that all carousel animals were hand-carved. But the Herschell-Spillman Company, the makers of our carousel, created quantities of affordable carousel animals through a shop production system, using machinery to rough out parts. You can read more on the history of our carousel in this blog post.

THF5584

And there you have it! Remember, odd and anachronistic as it might seem at times—the juxtaposed time periods, the buildings from so many different places, the specific people highlighted—there’s only one Greenfield Village!

Presenters at Daggett Farmhouse. / THF16450

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

#THFCuratorChat, Wright Brothers, world's fairs, Thomas Edison, research, railroads, Luther Burbank, Logan County Courthouse, J.R. Jones General Store, Henry Ford, Heinz, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Ford Motor Company, farm animals, Dr. Howard's Office, Daggett Farmhouse, Cohen Millinery, by Donna R. Braden, archives, agriculture, Abraham Lincoln

The Fair Lane Business Car: Restrained Luxury

Henry Ford's Private Railroad Car "Fair Lane," 1921 / THF186260

Just as many of today’s captains of industry and business leaders consider an executive jet to be a crucial part of their tool kit, so in the period prior to widespread air travel was the railroad business car considered an essential amenity. There are two basic categories of business cars, each with their equivalents in the modern world of business jets: the private car (at its most grandiose taking the form of “a palace on wheels”), owned by a wealthy individual or large corporation, and the chartered car, a well-appointed business car available for hire by companies or individuals as needed.

Business cars were attached at the rear of regularly scheduled passenger trains, according to arrangements made ahead of time with railroad companies. While the reliance on existing timetables and the inevitable complexities associated with being switched from one train to another en route might seem cumbersome and time-consuming to us, the opportunity to conduct business on the go, with food to order and a place to sleep, all in fully-staffed, well-appointed surroundings, made sense from a business standpoint: Work was accomplished, decisions were made, and the individuals concerned arrived in a better state than if they had been prey to the pitfalls of the ordinary traveler.

The interior of the Fair Lane, restored by The Henry Ford to as closely as possible resemble its appearance during Henry Ford’s ownership, is restrained, given Ford’s wealth. / THF186280

This car, Henry Ford’s Fair Lane, was one of the largest passenger railcars built when it was completed by Pullman in 1921. It is a private car, and as such reflects the taste of its owner, one of the wealthiest men on Earth. Paradoxically, Ford’s restrained taste and sense of occasion (think of the scale and finish of his house, given his wealth) resulted in a car that had more in common with the lower-key chartered cars—vehicles that incorporated the sumptuousness of the boardroom rather than the chairman’s own particular taste.

Even more paradoxically, traffic records reveal that the most extensive use to which Fair Lane was put was luxury transportation for Clara Ford and her close friends on shopping trips to New York City.

Explore many more images of the exterior and interior of the Fair Lane, including new 360-degree views of its compartments, in our Digital Collections.

This post is adapted from an educational document from The Henry Ford titled “Transportation: Past, Present, and Future—From the Curators.”

travel, railroads, Henry Ford Museum, Henry Ford, Fair Lane railcar

Fair Lane: The Fords’ Private Railroad Car

Fair Lane, Henry and Clara Ford’s private railroad car. / THF80274

Fair Lane, Henry and Clara Ford’s private railroad car. / THF80274Fair Lane, the private Pullman railroad car built for and used by Henry and Clara Ford, turns 100 years old in 2021. It provides a fascinating window into business and pleasure travel for the wealthy in the early 20th century.

By 1920, the Fords found it increasingly difficult to travel with any degree of privacy. Henry, in particular, was widely recognized by the public. He’d been generating major headlines for a decade, whether for his victory against the Selden Patent, his achievements with mass production and worker compensation via the Five Dollar Day, or his misguided attempt to end World War I with the Peace Ship. The Fords could travel privately for shorter distances by automobile, and their yacht, Sialia, provided seclusion when traveling by water. But anytime they entered a railroad station, the couple was sure to be pestered by the public and hounded by reporters. Their solution was to commission a private railroad car for longer overland trips.

Private railroad cars are nearly as old as the railroad itself. America’s first common-carrier railroad, the Baltimore & Ohio, opened in 1830. Little more than ten years later, President John Tyler traveled by private railcar over the Camden & Amboy Railroad to dedicate Boston’s Bunker Hill Monument in 1843. Not surprisingly, railroad executives and officials were also early users of private railroad cars. Cornelius Vanderbilt, president of the New York Central Railroad, used a private car when traveling over his line, both for business and for pleasure. For a busy railroad manager, the private railcar served as a mobile workspace where business could be conducted at distant points on the railroad line, far from company headquarters.

Pullman cars on the First Transcontinental Railroad, circa 1870. / THF291330

Following the Civil War, the Pullman Palace Car Company earned a reputation for its opulent public passenger cars with comfortable sleeping accommodations. Company founder George Pullman designed a private railcar to similar high standards. Pullman named the car P.P.C.—his company’s initials—and used it when traveling with his family. Pullman enjoyed lending the car to other dignitaries, by which he could simultaneously impress VIP passengers and advertise his company. Eventually, Pullman began renting the car out to patrons who could afford the daily rate of $85 (more than $2,000 today).

Clara and Henry Ford ordered their private railroad car from the Pullman Company on February 18, 1920. They hoped to have it delivered by that September, for a planned trip to inspect properties Henry had recently purchased in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. But delays pushed the car’s actual delivery date back by about nine months. Some of those delays were due to changes to the car’s interior. Clara designed the interior spaces, working with Sidney Houghton of London, who had earlier provided the same service for the Fords’ yacht.

The finished railroad car was delivered on June 23, 1921. The Fords named it Fair Lane—the same name they’d given to their estate in Dearborn, Michigan. (Fair Lane was the area in County Cork, Ireland, where Mr. Ford’s grandfather was born.) The final bill for the railcar came to $159,000 (about $2.3 million today). The Fords paid 25 percent of that cost upon placing their order, a further 25 percent during construction, and the final 50 percent on delivery.

Surely the finished Fair Lane was worth the wait and expense. The car included accommodations for six passengers and sleeping quarters for two additional staff members. When traveling, Fair Lane typically was staffed by a porter to attend to the passengers’ needs and a cook to prepare meals.

Fair Lane’s lounge offered the best views of passing scenery. / THF186264

At the rear of the car, a comfortable lounge provided a spot to read, relax, or simply watch the passing scenery through the large windows. An open porch-like platform at the very rear of the car was particularly enjoyable at moderate train speeds. Typically, Fair Lane was coupled to the end of a train, meaning that the view from the platform would not be obstructed.

Bedrooms in Fair Lane were cozy but comfortable. / THF186273

From the lounge, a narrow hallway ran most of the car’s length. Four bedrooms were located along the corridor. These rooms were cozy but comfortable. Each room had a bed, but berths could be unfolded from above to provide additional sleeping space if needed. Dressers and small desks rounded out the furnishings. Likewise, the bathrooms in Fair Lane were small but serviceable. Each one had hot and cold running water and a toilet. The master bath also included a shower.

Fair Lane’s passengers dined in this area. An on-board cook prepared meals to order. / THF186285

The dining area, near the front of the car, featured an extension table that comfortably seated six adults at one time. The chandelier, which hung directly above the table, was secured with guys that kept it from swaying as the car rolled down the railroad track. Built-in cabinets housed the car’s glassware and china. Clara Ford stocked Fair Lane with 144 various glasses, 169 pieces of silverware, and 230 crockery items. Wood posts and rails kept things from sliding around or falling out of the cabinets.

The car’s kitchen was small but sufficient for elaborate meals. / THF186289

Logically, the kitchen was located just in front of the dining room. Finished in stainless steel, the kitchen included an oven, a stovetop, a sink, and numerous additional cabinets. Food and supplies were loaded through the door at the car’s front end, so as not to disturb the riders farther back in the car. Staff quarters were located in the front of the car too. Compared with the other bedrooms, the staff room was sparse and utilitarian.

Using Fair Lane was not like driving a limousine or flying a private airplane. The railcar’s travels had to be coordinated with the various host railroads that operated America’s 250,000-mile rail network. Usually, Fair Lane was coupled to a regularly scheduled passenger train. The fee for pulling the private car was equivalent to 25 standard passenger tickets. One standard ticket on a train from Detroit to New York City in the early 1920s cost around $30, meaning the Fair Lane fee worked out to about $750 (around $10,000 today). If Fair Lane required a special movement—that is, if it was moved with a dedicated locomotive and not as a part of a regular train—then the fee jumped to the equivalent of 125 standard tickets.

The fee structure was different when Fair Lane moved over the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railroad. Henry Ford personally owned DT&I from 1920 to 1929. It was considered official railroad business when Mr. Ford used his private car on DT&I, so he did not need to pay a fare for himself. But he did pay fares for Fair Lane passengers who weren’t directly employed by DT&I.

Edsel and Eleanor Ford, Henry and Clara Ford, and Mina and Thomas Edison pose on the car’s rear platform about 1923. / THF97966

The Fords made more than 400 trips with Fair Lane in the two decades that they owned the car. Annual excursions took Henry and Clara Ford to their winter homes in Fort Myers, Florida, or Richmond Hill, Georgia. Likewise, Edsel and Eleanor Ford, Henry and Clara’s son and daughter-in-law, occasionally used Fair Lane to visit their own vacation home in Seal Harbor, Maine. The Fords hosted several special guests on the car too. Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge both spent time on the car, as did entertainer and humorist Will Rogers. Not surprisingly, Thomas and Mina Edison—among Henry and Clara Ford’s closest friends—also traveled aboard Fair Lane.

Clara Ford enjoyed trips to New York City, where she could visit friends or patronize specialty boutiques and department stores. Fair Lane could be coupled to direct Detroit–New York trains like New York Central’s Wolverine or Detroiter. Both trains arrived at the famous Grand Central Terminal in the heart of Manhattan. In 1922, an overnight run from the Motor City to the Big Apple on the Wolverine took 16 hours.

Both Henry Ford and Edsel Ford used Fair Lane when traveling on Ford Motor Company business. Chicago, New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C., were all frequent destinations on these trips. Of course, they’d travel to distant Ford Motor Company properties too, including those previously mentioned holdings in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Detroit’s Michigan Central Station, where most of Fair Lane’s journeys began and ended. / THF137923

Most of the car’s trips started and ended at Detroit’s Michigan Central Station, ten miles east of Dearborn. The large station had facilities to clean and stock Fair Lane, and crews to switch the car onto regular passenger trains. Michigan Central was a New York Central subsidiary, and New York Central trains provided direct service from Detroit to Chicago, New York, Boston, and many places in between. For longer trips, New York Central coordinated with additional railroad lines to transfer Fair Lane to other trains at connecting points, making the trip as seamless as possible for the Fords.

When Fair Lane wasn’t traveling out on a railroad, the car was stored in a shed built for it near Henry Ford’s flour mill on Oakwood Boulevard in Dearborn. The shed was just west of Dearborn’s present John D. Dingell Transit Center, where Amtrak trains stop today.

The Fords considered updating or replacing Fair Lane at different times. As early as March 1923, Ernest Liebold, Henry Ford’s personal secretary, wrote to the Pullman Company to inquire about building a larger car surpassing Fair Lane’s 82-foot length. Whatever Pullman’s reply, Ford did not place a new order. Twelve years later, Edsel Ford wrote to Pullman to ask about adding air conditioning to Fair Lane. The company responded with an estimate of $12,000 for the upgrade. Apparently, the cost was high enough for the Fords to once again consider building an entirely new, larger private railcar. The Pullman Company prepared a set of drawings for review but, once again, no order was placed.

Fair Lane in November 1942, at the end of its time with the Fords. / THF148020

By the early 1940s, Fair Lane was aging and in need of either significant repairs or outright replacement. Henry and Clara Ford were aging too, and weren’t traveling quite as much as they had in earlier years. On top of this, the United States joined World War II following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Wartime brought with it restrictions on materials, manufacturing, and travel—each on its own enough to sidetrack further work on Fair Lane. Somewhat reluctantly, Henry and Clara Ford sold their private railroad car in November 1942.

The St. Louis Southwestern Railway purchased Fair Lane from the Fords for $25,000. The company used the car for railroad business, carrying executives on its lines concentrated in Arkansas and Texas. In 1972, St. Louis Southwestern donated Fair Lane to the Cherokee National Historical Society. The organization used the car as an office space for the Cherokee Nation in Tahlequah, Oklahoma.

Richard and Linda Kughn purchased Fair Lane in 1982. They moved it to Tucson, Arizona, and began a four-year project to restore the car to its original Ford-era appearance. At the same time, they updated Fair Lane with modern mechanical, electrical, and climate-control systems. The Kughns enjoyed the refurbished railcar for several years before gifting it to The Henry Ford in 1996. Today Fair Lane is back in Dearborn—a testament to the golden age of railroad travel, as experienced by those with gilded budgets.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- 1924 Railroad Refrigerator Car, Used by Fruit Growers Express

- Ingersoll-Rand Number 90 Diesel-Electric Locomotive, 1926

- Allegheny Locomotive: Can-Do Experience

- Revolution on Rails: Refrigerated Box Cars

21st century, 20th century, travel, railroads, Michigan, Henry Ford Museum, Henry Ford, Fair Lane railcar, Detroit, Dearborn, Clara Ford, by Matt Anderson

Ford Methods and the Ford Shops

THF97674

In 1913, Ford Motor Company combined the standardization of interchangeable parts with the subdivision of labor and the fluid movement of work to workers to create the world’s most influential assembly line. We are unusually fortunate that two keen observers of industry, Horace Lucien Arnold and Fay Leone Faurote, were there to document it.

Arnold, a correspondent for The Engineering Magazine, grasped the significance in Ford’s work and began a series of articles on the company’s Highland Park factory. After Arnold’s untimely death, Faurote completed and compiled the articles in the 1915 study Ford Methods and the Ford Shops. The book’s detailed descriptions, numerous photographs and careful diagrams give us a vivid window into Highland Park at a seminal moment in manufacturing history.

Looking back now, the most remarkable aspect of Ford Methods and the Ford Shops is the liberal level of access Ford gave to its authors. It is difficult to imagine Google or Apple opening their doors to today’s press and giving unfettered access to employees, workspaces, and sensitive production figures. The company’s cooperation speaks volumes about Henry Ford’s confidence in Highland Park. He knew that his methods were far ahead of his competitors, and there was little fear of them catching up too quickly.

Workers place magnets on Model T flywheels, 1913. Fittingly, successful experiments with a moving magneto assembly line “sparked” Ford’s adoption of assembly line techniques throughout Highland Park. / THF96001

The assembly line came to Ford Motor Company in stages. Around April 1, 1913, flywheel magnetos were placed on moving lines. Instead of one worker completing one flywheel in some 20 minutes, a group of workers stood along a waist-high platform. Each worker assembled some small piece of the flywheel and then slid it along to the next person. One whole flywheel came off the line every 13 minutes. With further tweaking, the assembly line produced a finished flywheel magneto in just five minutes.

Flow charts and maps in the book illustrated the logical, sequential arrangement of machine tools at Highland Park. / THF600582

It was a genuine “eureka” moment. Ford soon adapted the assembly line to engines, and then transmissions, and, in August 1913, to complete chassis. The crude “slide” method was replaced with chain-driven delivery systems that not only reduced handling but also regulated work speed. By early 1914, the various separate production lines had fused into three continuous lines able to churn out a finished Model T every 93 minutes—an extraordinary improvement over 12½ hours per car under the old stationary assembly methods.

Workers lower an engine into a Model T chassis, 1913. Note that the line is not yet chain-driven. Ford constantly improved the assembly line in search of time and cost savings. / THF91696

The incredible time and cost savings realized through the assembly line allowed Henry Ford to lower the Model T’s price, which increased demand for the car, which then prompted Ford to seek even greater manufacturing efficiencies. This feedback loop ultimately produced some 15 million Model Ts selling for as little as $260 each.

The peak annual Model T production of 1.8 million in 1923 was still years away when Arnold and Faurote made their study. They did not capture Ford’s assembly line in a fully realized form. In fact, the line never was finished. It existed in a state of flux, under constant review for any potential improvements. Adjusting the height of a work platform might save a few seconds here, while moving a drill press might shave some more seconds there. Several such small changes could yield large productivity gains.

Ford Methods and the Ford Shops captures a manufacturer that has just discovered the formula for previously unimagined production levels. The assembly line is groundbreaking, and Ford knows it. The company’s openness with its methods, and Arnold’s and Faurote’s efforts to document and publicize them, helped make the Model T assembly line the industrial milestone that we still celebrate more than a century later.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. This post was adapted from a 2013 post in our Pic of the Month series.

Additional Readings:

- The Wool Carding Machine

- Positioning and Synchronicity on Paper

- Fordson Tractor No. 100,000

- Thomas Blanchard’s Wood Copying Lathe

research, Model Ts, cars, Ford Motor Company, manufacturing, by Matt Anderson, Henry Ford, books

Henry Ford: Case Study of an Innovator

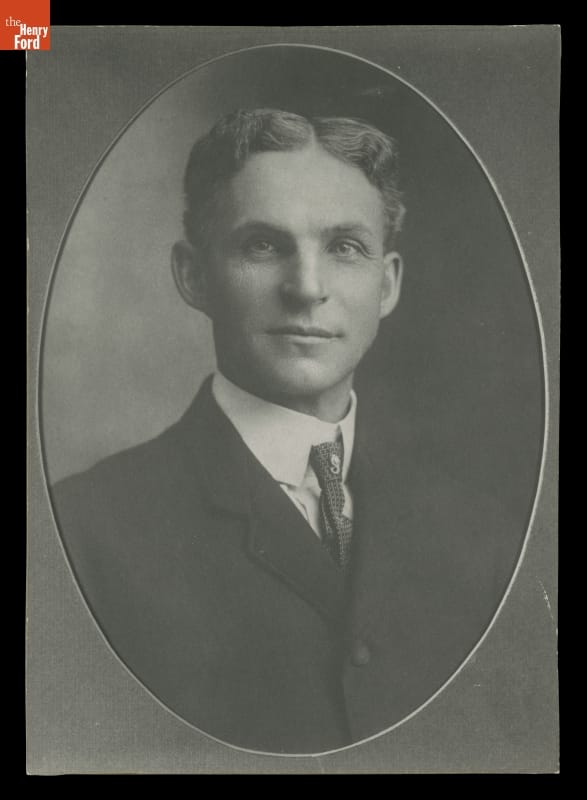

Henry Ford’s first official Ford Motor Company portrait, 1904. / THF97952

Henry Ford did not invent the automobile. But more than any other single individual, he was responsible for transforming the automobile from an invention of unknown utility into an innovation that profoundly shaped the 20th century and continues to affect the 21st. His work at Ford Motor Company revolutionized the automotive industry, setting new standards for production and accessibility.

Innovators change things. They take new ideas—sometimes their own, sometimes other people’s—and develop and promote those ideas until they become an accepted part of daily life. Innovation requires self-confidence, a taste for taking risks, leadership ability, and a vision of what the future should be. Henry Ford had all these characteristics, but it took him many years to develop all of them fully.

Portrait of the Innovator as a Young Man

Ford’s beginnings were perfectly ordinary. He was born on his father’s farm in what is now Dearborn, Michigan, on July 30, 1863. At this time, most Americans were born on farms, and most looked forward to being farmers themselves. Early on, Ford demonstrated some of the characteristics that would make him successful. In his family, he became infamous for taking apart his siblings’ toys as well as his own. He organized other boys to build rudimentary waterwheels and steam engines. He learned about full-size steam engines by becoming acquainted with the engines’ operators and pestering them with questions. He taught himself to fix watches and used the watches themselves as textbooks to learn the basics of machine design. Thus, at an early age, Ford demonstrated curiosity, self-confidence, mechanical ability, the capacity for leadership, and a preference for learning by trial and error. These characteristics would become the foundation of his whole career.

Artist Irving Bacon depicted Henry Ford in his first workshop, along with friends, in this 1938 painting. / THF152920

Ford could simply have followed in his father’s footsteps and become a farmer. But young Henry was fascinated by machines and was willing to take risks to pursue that fascination. In 1879, he left the farm to become an apprentice at a machine shop in Detroit. Over the next few years, he held jobs at several places, sometimes moving when he thought he could learn more somewhere else. He returned home in 1882 but did little farming. Instead, he operated and serviced portable steam engines used by farmers, occasionally worked in factories in Detroit, and cut and sold timber from 40 acres of his father’s land.

By now, Ford was demonstrating another characteristic—a preference for working on his own rather than for somebody else. In 1888, Ford married Clara Bryant, and in 1891 they moved to Detroit. Ford had taken a job as night engineer for the Edison Electric Illuminating Company—another risk on his part, because he did not know a great deal about electricity at this point. He took the job in part as an opportunity to learn.

Henry Ford (third from left, in white coat) with other employees at Edison Illuminating Company Plant, November 1895. / THF244633

Early Automotive Experiments: Failure and Then Success

Henry was a skilled student, and by 1896 had risen to chief engineer of the Illuminating Company. But he had other interests. He became one of the scores of other people working in barns and small shops trying to make horseless carriages. Ford read about these other efforts in magazines, copying some of the ideas and adding some of his own, and convinced a small group of friends and colleagues to help him. This resulted in his first primitive automobile, the Quadricycle, completed in 1896. A second, more sophisticated car followed in 1898. These early experiments laid the groundwork for his future endeavors in the automotive industry.

Henry Ford’s 1896 Quadricycle Runabout, the first car he built. / THF90760

Ford now demonstrated one of his most important characteristics—the ability to articulate a vision and convince other people to sign on and help him achieve that vision. He convinced a group of businessmen to back him in the biggest risk of his life—starting a company to make horseless carriages. But Ford knew nothing about running a business, and learning by doing often involves failure. The new company failed, as did a second. His first venture, the Detroit Automobile Company, failed due to the poor quality of its vehicles. Ford tried again, this time with the Henry Ford Company. But disputes over the new company’s direction soon caused Ford and his investors to part ways.

To revive his fortunes, Ford took bigger risks, building and even driving a pair of racing cars. The success of these cars attracted additional financial backers, and on June 16, 1903, just before his 40th birthday, Henry incorporated his third automobile venture, the Ford Motor Company.

The early history of Ford Motor Company illustrates another of Henry Ford’s most valuable traits—his ability to identify and attract outstanding talent. He hired a core of young, highly competent people who would stay with him for years and make Ford Motor Company into one of the world’s great industrial enterprises. He hired a core of young, highly competent people who would stay with him for years, reshaping America’s automotive industry while building Ford Motor Company into one of the world’s great industrial enterprises.

Print of Norman Rockwell's painting, "Henry Ford in First Model A on Detroit Street." / THF288551

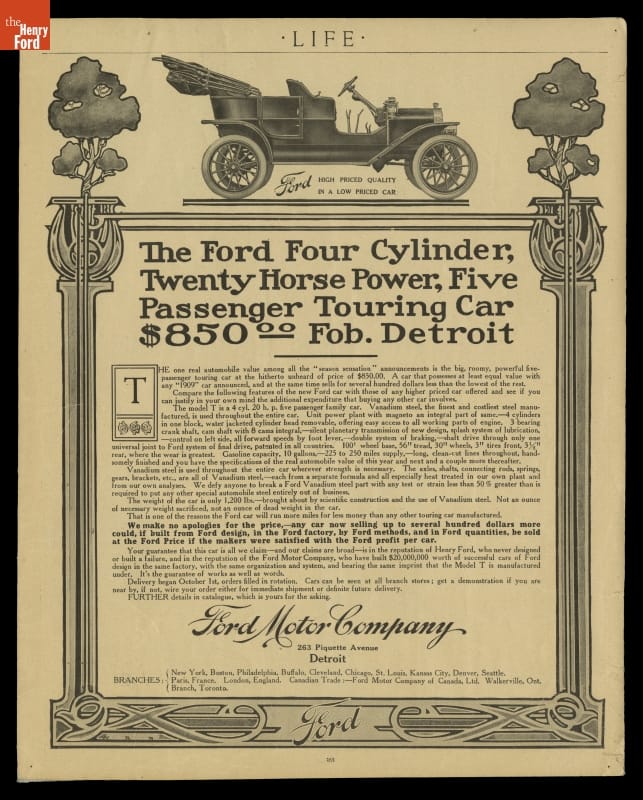

The new company’s first car was called the Model A, and a variety of improved models followed. In 1906, Ford’s 4-cylinder, $600 Model N became the best-selling car in the country. But by this time, Ford had a vision of an even better, cheaper “motorcar for the great multitude.” Working with a small group of employees, he came up with the Model T, introduced on October 1, 1908. The Model T was a game-changer, designed to be simple, reliable, and ultimately affordable for the average American.

The Automobile: A Solution in Search of a Problem

As hard as it is for us to believe, in 1908 there was still much debate about exactly what automobiles were good for. We may see them as a necessary part of daily life, but the situation in 1908 was very different. Americans had arranged their world to accommodate the limits of the transportation devices available to them. People in cities got where they wanted to go by using electric street cars, horse-drawn cabs, bicycles, and shoe leather because all the places they wanted to go were located within reach of those transportation modes.

This Boston street scene, circa 1908, shows pedestrians and horse-drawn carriages on the road—but no cars. / THF203438

Most of the commercial traffic in cities still moved in horse-drawn vehicles. Rural Americans simply accepted the limited travel radius of horse- or mule-drawn vehicles. For long distances, Americans used our extensive, well-developed railroad network. People did not need automobiles to conduct their daily activities. Rather, the people who bought cars used them as a new means of recreation. They drove them on joyrides into the countryside. The recreational aspect of these early cars was so important that people of the time divided motor vehicles into two large categories: commercial vehicles, like trucks and taxicabs, and pleasure vehicles, like private automobiles. The term “passenger cars” was still years away. The automobile was an amazing invention, but it was essentially an expensive toy, a plaything for the rich. It was not yet a true innovation.

Henry Ford had a wider vision for the automobile. He summed it up in a statement that appeared in 1913 in the company magazine, Ford Times:

“I will build a motor car for the great multitude. It will be large enough for the family but small enough for the individual to run and care for. It will be constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise. But it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one—and enjoy with his family the blessings of hours of pleasure in God’s great open spaces.”

This 1924 Ford ad, part of a series, echoes the vision expressed 11 years earlier by Henry Ford: “Back of all of the activities of the Ford Motor Company is this Universal idea—a wholehearted belief that riding on the people’s highway should be in easy reach of all the people.” / THF95501

It was this vision that moved Henry Ford from inventor and businessman to innovator. To achieve his vision, Ford drew on all the qualities he had been developing since childhood: curiosity, self-confidence, mechanical ability, leadership, a preference for learning by trial and error, a willingness to take risks, and an ability to identify and attract talented people.

One Innovation Leads to Another

Ford himself guided a design team that created a car that pushed technical boundaries. The Model T’s one-piece engine block and removable cylinder head were unusual in 1908 but would eventually become standard on all cars. The Ford’s flexible suspension system was specifically designed to handle the dreadful roads that were then typical in the United States. The designers utilized vanadium alloy steel that was stronger for its weight than standard carbon steel. The Model T was lighter than its competitors, allowing its 20-horsepower engine to give it performance equal to that of more expensive cars. The Model T forever changed the automotive industry and American culture. Its impact can still be felt today.

1908 advertisement for the 1909 Ford Model T. In advertisements, Ford Motor Company emphasized key technological features and the low prices of their Model Ts. Ford's usage of vanadium steel enabled the company to make a lighter, sturdier, and more reliable vehicle than other early competitors. / THF122987

The new Ford car proved to be so popular that Henry could easily sell all he could make, but he wanted to be able to make all he could sell. So Ford and his engineers began a relentless drive both to raise the rate at which Model Ts could be produced and to lower the cost of production.

In 1910, the company moved into a huge new factory in Highland Park, a city just north of Detroit. Borrowing ideas from watchmakers, clockmakers, gunmakers, sewing machine makers, and meat processors, Ford Motor Company had, by 1913, developed a moving assembly line for automobiles. But Ford did not limit himself to technical improvements.

When his workforce objected to the relentless, repetitive work that the line entailed, Ford responded with perhaps his boldest idea ever—he doubled wages to $5 per day. With that one move, he stabilized his workforce and gave it the ability to buy the very cars it made. He hired a brilliant accountant named Norval Hawkins as his sales manager. Hawkins created a sales organization and advertising campaign that fueled potential customers’ appetites for Fords. Model T sales rose steadily while the selling price dropped. By 1921, half the cars in America were Model Ts, and a new one could be had for as little as $415.

Norval Hawkins headed the sales department at Ford Motor Company for 12 years, introducing innovative advertising techniques and increasing Ford’s annual sales from 14,877 vehicles in 1907 to 946,155 in 1919. / THF145969

Through these efforts, Ford turned the automobile from an invention bought by the rich into a true innovation available to a wide audience. By the 1920s, largely as a result of the Model T’s success, the term “pleasure car” was fading away, replaced by “passenger car.” Ford’s moving assembly line and $5 day ushered in a new era of mass production and affordability. American society itself was transformed as motorists were free to travel where they wanted, when they wanted.

The assembly line techniques pioneered at Highland Park spread throughout the auto industry and into other manufacturing industries as well. The high-wage, low-skill jobs pioneered at Highland Park also spread throughout the manufacturing sector. Advertising themes pioneered by Ford Motor Company are still being used today. Ford’s curiosity, leadership, mechanical ability, willingness to take risks, ability to attract talented people, and vision produced innovations in transportation, manufacturing, labor relations, and advertising. His legacy is preserved at places like Greenfield Village, showcasing his impact on American life and the evolution of the automotive industry.

What We Have Here Is a Failure to Innovate

Henry Ford was slow to admit that customers no longer wanted the Model T. However, in 1927, he finally acknowledged that shift, and Henry Ford and his son, Edsel Ford, drove this last Model T—number 15,000,000—off the assembly line at Highland Park. / THF135450

Henry Ford’s great success did not necessarily bring with it great wisdom. In fact, his very success may have blinded him as he looked to the future. The Model T was so successful that he saw no need to significantly change or improve it. He did authorize many detail changes that resulted in lower cost or improved reliability, but there was never any fundamental change to the design he had laid down in 1907.

He was slow to adopt innovations that came from other carmakers, like electric starters, hydraulic brakes, windshield wipers, and more luxurious interiors. He seemed not to realize that the consumer appetites he had encouraged and fulfilled would continue to grow. He seemed not to want to acknowledge that once he started his company down the road of innovation, it would have to keep innovating or else fall behind companies that did innovate. He ignored the growing popularity of slightly more expensive but more stylish and comfortable cars, like the Chevrolet, and would not listen to Ford executives who believed it was time for a new model.

But Model T sales were beginning to slip by 1923, and by the late 1920s, even Henry Ford could no longer ignore the declining sales figures. In 1927, he reluctantly shut down the Model T assembly lines and began the design of an all-new car. It appeared in December 1927 and was such a departure from the old Ford that the company went back to the beginning of the alphabet for a name—it was called the Model A.

Edsel and Henry Ford introduce the new Model A at the Ford Industrial Exposition in New York in January 1928. Edsel had worked to convince his father to replace the outmoded Model T with something new. / THF91597

One area where Ford did keep innovating was in actual car production. In 1917, he began construction of a vast new plant on the banks of the Rouge River southwest of Detroit. This plant would give Ford Motor Company complete control over nearly all aspects of the production process. Raw materials from Ford mines would arrive on Ford boats, and would be converted into iron and steel, which were transformed into engines, transmissions, frames, and bodies. Glass and tires would be made onsite as well, and all of this would be assembled into completed cars. Assembly of the new Model A was transferred to the Rouge. Eventually the plant would employ 100,000 people and generate many innovations in auto manufacturing. The River Rouge complex became a symbol of Ford's ambition and scale, a testament to his vision for vertically integrated production.

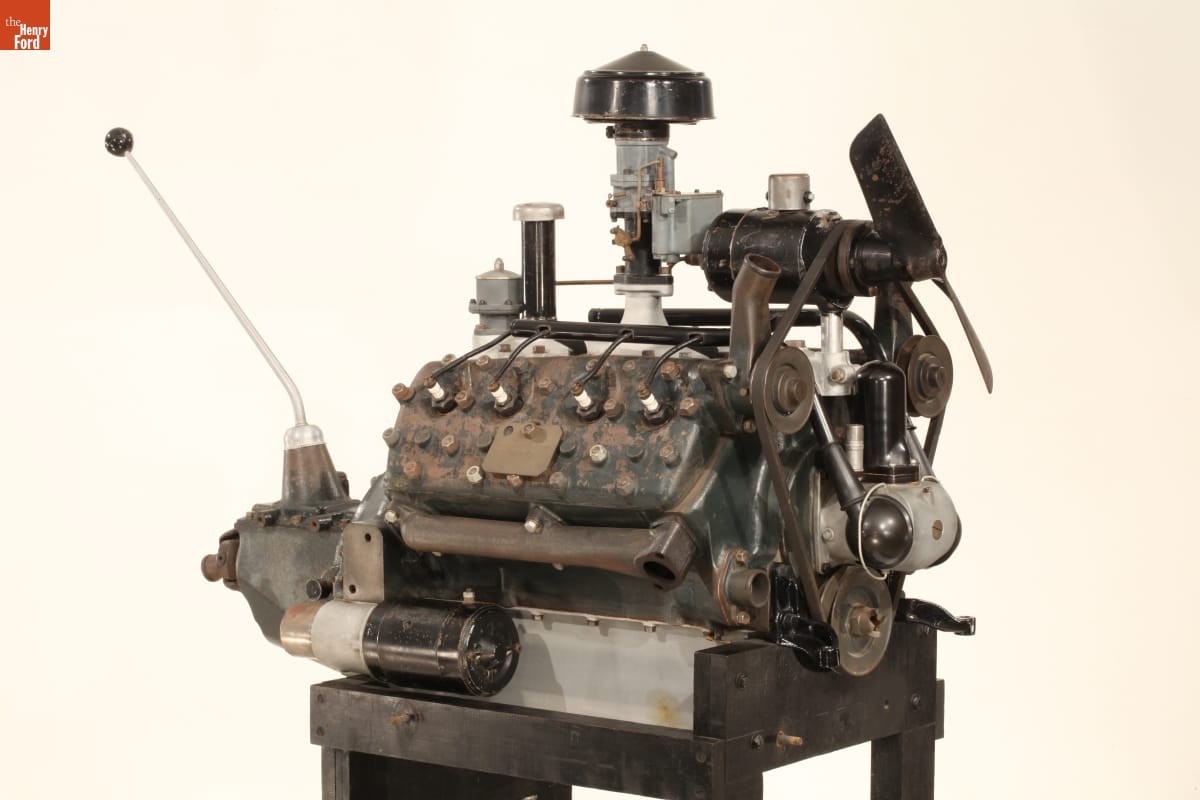

But improvements in manufacturing were not enough to make up for the fact that Henry Ford was no longer a leader in automotive design. The Model A was competitive for only four years before needing to be replaced by a newer model. In 1932, at age 69, Ford introduced his last great automotive innovation, the lightweight, inexpensive V-8 engine. It represented a real technological and marketing breakthrough, but in other areas Fords continued to lag behind their competitors. The Ford factory continued to evolve, but the company faced new challenges in keeping up with changing consumer preferences and technological advancements in the automotive industry.

The V-8 engine was Henry Ford’s last great automotive innovation. This is the first V-8 engine produced, which is on exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF101039

By 1936, the company that once sold half of the cars made in America had fallen to third place behind both General Motors and the upstart Chrysler Corporation. By the time Henry Ford died in 1947, his great company was in serious trouble, and a new generation of innovators, led by his grandson Henry Ford II, would work long and hard to restore it to its former glory. Henry’s story is a textbook example of the power of innovation—and the power of its absence. His contributions to the automotive industry and American society are undeniable, but his later resistance to change serves as a cautionary tale.

Bob Casey is former Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. This post is adapted from an educational document from The Henry Ford titled “Henry Ford and Innovation: From the Curators.”

Detroit, Michigan, Dearborn, 20th century, 19th century, quadricycle, Model Ts, manufacturing, Henry Ford, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Ford Motor Company, entrepreneurship, engines, engineering, cars, by Bob Casey, advertising

“Whenever Henry Ford visited England, he always liked to spend a few days in the Cotswold Country, of which he was very fond … during these sojourns I had many happy times driving Mr. Ford around the lovely scenes which abound in this part of Britain.”

—Herbert Morton, Strange Commissions for Henry Ford

A winding road through a Cotswold village, October 1930. / THF148434, detail

The Cotswolds Catch Henry Ford’s Eye

Henry Ford loved the Cotswolds, a rural region in southwest England—nearly 800 square miles of rolling hills, pastures, and small villages.

During the Middle Ages, a vibrant wool trade brought the Cotswolds great prosperity—at its heart was a breed of sheep known as Cotswold Lions. For centuries, the Cotswold region was well-known throughout Europe for the quality of its wool. Raising sheep, trading in wool, and woolen cloth fueled England’s economic growth from the Middle Ages to the Industrial Revolution. Cotswold’s prosperity and its rich belt of limestone that provided ready building material resulted in a distinctive style of architecture: limestone homes, churches, shops, and farm buildings of simplicity and grace.

During Henry Ford’s trips to the Cotswolds in the 1920s, he became intrigued with the area’s natural beauty and charming architecture—all those lovely stone buildings that “blossomed” among the verdant green countryside and clustered together in Cotswold’s picturesque villages. By early 1929, Ford had decided he wanted to acquire and move a Cotswold home to Greenfield Village.

A letter dated February 4, 1929, from Ford secretary Frank Campsall described that Ford was looking for “an old style that has not had too many changes made to it that could be restored to its true type.” Herbert Morton, Ford’s English agent, was assigned the task of locating and purchasing a modest building “possessing as many pretty local features as might be found.” Morton began to roam the countryside looking for just such a house. It wasn’t easy. Cotswold villages were far apart, so his search covered an extensive area. Owners of desirable properties were often unwilling to sell. Those buildings that were for sale might have only one nice feature—for example, a lovely doorway, but no attractive window elements.

Cotswold Cottage (buildings shown at left) nestled among the rolling hills in Chedworth, 1929–1930. / THF236012

Herbert Morton was driving through the tiny village of Lower Chedworth when he saw it. Constructed of native limestone, the cottage had “a nice doorway, mullions to the windows, and age mellowed drip-stones.” Morton knew he had found the house he had been looking for. It was late in the day, and not wanting to knock on the door and ask if the home was for sale, Morton returned to the town of Cheltenham, where he was staying.

The next morning Morton strolled along a street in Cheltenham, pondering how to approach the home’s owner. He stopped to look into a real estate agent’s window—and saw a photograph of the house, which was being offered for sale! Later that day, Morton arrived in Chedworth, and was greeted by the owner, Margaret Cannon Smith, and her father. The cottage, constructed out of native limestone in the early 1600s, had begun life as a single cottage, with the second cottage added a bit later.

Interior of Cotswold Cottage, 1929-1930. / THF236052