Posts Tagged henry ford

Celebrating Ninety Years of Inspiration: Collecting Through the Decades

Aerial View of Henry Ford Museum under Construction, Late October or Early November 1929. THF98555

Henry Ford dedicated his museum and village on October 21, 1929, marking the 50th anniversary of Thomas Edison’s first successful light bulb test. Ford named his new complex The Edison Institute of Technology to honor his friend and lifelong hero. This year, Henry Ford’s museum and village complex – now known as The Henry Ford – celebrates its 90th anniversary. Throughout 2019, we’ll be reflecting decade-by-decade on significant additions to the collection he began, with a focus on our institution's evolving collecting philosophies.

Our Origins

Although Henry Ford became one of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful industrialists, he never forgot the values of the rural life he had left behind growing up on a farm. His interest in collecting began in 1914, as he searched for McGuffey Readers to verify a long-remembered verse from one of his old grade school recitations. Soon, the clocks and watches he had loved tinkering with and repairing since childhood grew into a collection of their own. Before long, he was accumulating the objects of ordinary people, items connected with his heroes and from his own past, and examples of industrial progress.

Contrary to the notorious quote, Henry Ford never really believed that history is bunk. What he believed was bunk was the kind of history taught in schools—that emphasized kings and generals and omitted the lives of ordinary folks. In 1916, Ford began to imagine building a museum that would show people a kind of history he believed was worth preserving.

Restorations

In 1919, Henry Ford learned that his birthplace was at risk because of a road improvement project. He took charge—moving the farmhouse and restoring it to the way he remembered it from the time of his mother’s death in 1876, when he was 13. He and his assistants combed the countryside for items that he remembered and insisted on tracking down.

He followed this up by restoring his old one-room school, Scotch Settlement School; the 1686 Wayside Inn in South Sudbury, Massachusetts (with a plan to develop a “working” colonial village); and the 1836 Botsford Inn in Farmington, Michigan, a stagecoach inn where he and his wife Clara had once attended old-fashioned dances. These restorations gave Ford many opportunities to add to his rapidly growing collections while honing his ideas for his own historic village.

Something of Everything

In the early 1920s, Henry Ford moved his growing hoard of antiques into a vacated tractor assembly building. The objects fit every description. Large items hung from rafters; smaller ones sat on makeshift benches and racks. Watches and clocks hung along the wall. Henry and his wife Clara enjoyed sharing their relics with others. Once people learned Ford was collecting objects for a museum, they flooded his office with letters offering to give or sell him antiques.

Frank Campsall, Charles Newton, and Henry Ford at the Ford Engineering Laboratory with Donations for Henry Ford's Museum, 1928 THF126101

Ford also sent out assistants to help him find and acquire the kinds of objects he felt were important to preserve. Goods intended for the museum arrived in Dearborn almost daily—sometimes by the train-car full. By the late 1920s, Henry Ford had become the primary collector of Americana in the world.

One of the most well-known artifacts in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation is the rocking chair used by Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre the night of his assassination, April 14, 1865. Originally purchased as part of a parlor suite, the rocking chair was intended for use in a reception room in Ford's Theatre, which opened in 1863. The parlor suite was purchased by Harry Clay Ford (no relation to Henry Ford), manager of the Theatre. However, the comfortable rocking chair began to be used by ushers during their "down" time and the fabric became soiled by their hair oil. This stain is still visible on the back. Sometime in 1864, Harry Ford had the chair moved to his apartment across the alley from the Theatre in a belated attempt to keep it clean.

Beginning with the Theatre's opening in 1863, President Lincoln became a frequent visitor. At some point, Mr. Ford began to supply the president and his party with comfortable seating furniture. Apparently, the president preferred this rocking chair, perhaps, due to his height. On the afternoon of April 14th, the chair was brought to the president's box along with a matching sofa and side chair. After the assassination, the Theatre and its contents was seized by the federal government.

After its seizure, the chair remained in the private office of the Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton. In 1867, the chair was transferred to the Department of the Interior and then sent to the Smithsonian Institution and placed in storage. For all practical purposes, the chair vanished from the public for half a century. Documentation at the Smithsonian indicates that it was catalogued into the collection in 1902. In 1929, the rocker was returned to Blanche Chapman Ford, widow of Harry Clay Ford.

Mrs. Ford sold the chair at auction through the Anderson Galleries in New York on December 17, 1929. The purchaser was Israel Sack, the dean of antique American furniture dealers, and an agent of Henry Ford. Sack had observed that Ford delighted in furniture that had association with American historical figures. Sack, in turn, offered the chair to Mr. Ford, who purchased it and carefully documented its arrival in Greenfield Village in early 1930. There, the chair resided in the Logan County, Illinois Court House where Lincoln practiced law as a circuit rider in the 1840s. Mr. Ford had moved the Court House to Greenfield Village in 1929--the chair became the centerpiece of his Lincoln collection. In 1979, as part of the institution's 50th anniversary, the chair moved from the Court House to the Museum, where it remains today.

Learn more about the Lincoln rocker here.

Beyond the Lincoln Chair, our collections experts have selected a number of other items acquired before and during the 1920s that reflect our early collecting philosophy.

Ned Kendall Keyed Bugle

Country dances, town bands. America’s musical traditions held personal meaning for Henry Ford. In 1928, Ford purchased Daniel S. Pillsbury’s extraordinary collection of 175 early band instruments.This 1837 keyed bugle from the Pillsbury collection had belonged to Ned Kendall-- keyed bugle virtuoso and leader of the Boston Brass Band. During the 19th century, community bands provided much of the music enjoyed by everyday Americans. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

Argand Lamp, 1790-1850

This lamp expresses the collecting philosophy that Henry Ford and his staff were using in developing the lighting collection. They were seeking to acquire examples documenting the changes in lighting technology that led to the introduction of the electric light bulb in 1879. This Argand lamp was one the first oil lamps that created a flame burning brighter than a single candle. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

Menlo Park Laboratory

Among the most iconic and significant buildings in Greenfield Village, the re-creation of the Menlo Park Compound was a very important achievement for Henry Ford. Work began to salvage what was left of Menlo Park in the late 1920s. By early 1929, original bits of the Main Lab, the Carbon Shed, and the Glass House came together with the re-created Library, and Machine Shop to bring Menlo Park to life. On October 21, 1929, the entire project received Thomas Edison’s stamp of approval, with the exception of it being too clean. - Jim Johnson, Director, Greenfield Village and Curator, Historic Structures & Landscapes

1896 Ford Quadricycle

It all began with the Quadricycle. Ford Motor Company, the Model T, The Henry Ford -- none of it would have happened if Henry Ford hadn't finished this little car in June 1896. He sold it a few months later for $200 -- money he promptly spent building his second car. Fast forward to 1904. With Ford Motor Company blooming and Henry perhaps feeling nostalgic, he paid $65 to buy the Quadricycle back. It was arguably Mr. Ford's first significant acquisition documenting his own life and achievements. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

Platform Rocker, 1882-1900

In 1928, Henry Ford became interested in the estate of the late Josephine Moore Caspari of Detroit. A wealthy heiress, she married a Spanish riding master but divorced him just four years later after discovering that he had married another in Germany. The divorce was the talk of the town. Ms. Caspari became a recluse; bolting the doors to her large Italianate mansion and positioning two large dogs to guard the entry. When she passed away, her estate was set to be sold. Intrigued, Henry Ford bought many items from the estate, including this platform rocker made by George Hunzinger. Hunzinger’s platform spring rocking chairs combined numerous inventions, creating a more comfortable and quiet rocking experience. - Katherine White, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Paper Horseshoe Filament Lamp Used at New Year's Eve Demonstration of the Edison Lighting System, 1879

Electrical engineer William Joseph Hammer began working for Thomas Edison in 1879 and soon started collecting the incandescent lamps they were developing at Edison's Menlo Park complex in New Jersey. After Edison created the first practical incandescent lamp in October 1879, news spread and the public clamored to view his achievement. On New Year's Eve, thousands of people streamed into Menlo Park to see the first public display of Edison's electric light, including this surviving example. In 1929, a group of Edison's former employees known as the "Edison Pioneers" donated Hammer's collection, which contained this lamp, to Henry Ford's new museum the "Edison Institute." - Ryan Jelso, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Letter from Thomas Edison to His Parents, October 30, 1870

This brief letter from a 23-year-old Thomas Edison to his parents provides insight into the early growth of Edison’s work on telegraph instruments. As part of a much larger collection acquired in 1929 through a gift from the Edison Pioneers, the letter also reflects Henry Ford’s many efforts to honor his friend and lifelong hero, which included the re-creation of Edison’s Menlo Park Laboratory and the naming of his new museum and village complex The Edison Institute of Technology. - Brian Wilson, Senior Manager Archives and Library, Benson Ford Research Center

Eastman Kodak Box Camera, 1888-1889

Henry Ford drew on personal and professional connections to build his extensive museum collection. Following a conversation with Ford, photography pioneer George Eastman donated a group of significant cameras that included this one: an example of Eastman’s first “Kodak” camera (the first designed for roll film), which revolutionized popular photography. - Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Ambler's Mowing Machine, circa 1836

Henry Ford relied on antique dealers to ferret out "firsts," and the Ambler Moving Machine is an example. Felix Roulet acquired the machine for Ford. He convinced Ford of the merits of the Ambler mower by quoting a paragraph printed in Merritt Finley Miller’s booklet, The Evolution of the Reaping Machine, published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Office of Experiment Stations, Bulletin No. 103 (1902), page 28: “Enoch Ambler of New York, obtained a patent Dec 23, 1834 about which little can be learned. It is understood, however, that he had the first wrought-iron finger bar with steel guards & shoes…” Roulet described the machine to Ford in correspondence, and he assured Ford that “this machine will be a gem in [sic] Mr Fords collection." The machine arrived at Ford Motor Company on November 23, 1924. - Debra Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

#Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, Greenfield Village, Henry Ford Museum, Henry Ford, THF90

In the early years of World War I hundreds of thousands of Belgian refugees fled to England to escape their war torn country. Lord Perry, of Ford of England, worked with Henry Ford to establish a home for these refugees to help get them on their feet while they found work and homes of their own in England. For this purpose, Perry leased Oughtrington Hall in Cheshire, England with money donated from Henry and Clara Ford to house up to 100 refugees at a time.

The idea of helping the refugees appears to have been discussed in person between Perry and the Fords in October 1914 while Perry was visiting the states. On returning to England, Perry wrote Clara Ford in December of 1914, saying he’d secured Oughtrington Hall for $35.00 per month, with the landlord giving the rent money to the Belgian Refugee Fund. By December 29, 1914 the first group of refugees had arrived consisting of “six better class adults, 14 better class children and 3 nurses for the children; one wounded Belgian Officer and his wife; 7 discharged Belgian soldiers (these men have been wounded and are sufficiently recovered from their wounds to be discharged from Hospital, but not well enough to rejoin the Army; they cannot go back to their homes in Belgium because they have been destroyed); 4 working class married couples with 5 young children, 3 elderly single men.” The first group of refugees was picked by Perry and included those he considered “the better class” and those of the “working class.” Perry envisioned the wealthy refugees overseeing the children and the working class, and the working class performing the housekeeping, and cooking. The “servant class,” however, rebelled at this notion and Perry was soon writing to Clara noting the working class, “imagine themselves guests and see no reason why they should not be treated as guests with a consequence that they expect to be waited on etc.” Perry compromised by proposing they be paid a servants wage for their labor which would be payable after they left the house to return to Belgium or other employment. The number of refugees in the house continued to grow quickly, by February 1915 there were 93 refugees in the house and in March, 110.

To oversee the group’s needs, Perry appointed a former Ford Motor Company agent in Brussels, Vandermissen as he was the only one in the original group who could speak English. The initial group of refugees battled outbreaks of many contagious diseases, including a scarlet fever and small pox scare. Perry was unable to find a Belgian doctor for some time, so he had to hire local doctors and even use the Manchester plant doctor to see to the refugees needs, however the language gap proved a problem. Eventually, a Belgian doctor was hired, and a surgery and doctor’s office were set up on the grounds. A chapel was built, and a Belgian priest was brought in to see to the refugees’ spiritual needs. Oughtrington Hall was one of the few refugee homes that could house large families and there were always many children in the hall. A nursery and school were established, and the indoor tennis court was heated with a stove to provide a play area for the children. The refugees also raised and sold pigs and cows on the 30 acres attached to the hall.

Perry and his wife, Katie, spent countless hours arranging for the lease, administrating the house, and seeing to the needs of the refugees. They donated much of their own furniture and clothing, “Katie and I have both taken all of our clothes, excepting those that we are actually wearing – both suits and under-clothes – and used them for fitting out some of these poor people.” Perry also requested the Fords send their second-hand clothing to the refugees as well “if it is not too much trouble, it would be nice to receive from you any old clothes of Edsel’s or Mr. Ford’s which could be spared…Such clothes would be of much better quality than we can think of buying, and would further more save money,” a request the Fords followed through with (although only one woman in the hall could fit into Clara’s shoes). However, not all the refugees’ needs were met immediately. When the boiler went out in 1915, Perry refused to pay for a new one as they were only renting, demanding the landlord replace the unit, but it took the landlord sometime to make up his mind and “meanwhile the poor Belgians are very cold.” The money the Fords provided not only furnished the house, and provided food, but also bought clothing, toiletries, and basic items for the refugees (many of whom had left the country with no extra clothes or personal possessions) as well as provided the refugees with pocket money from $0.50 - $1.00 each per week. Perry also purchased subscriptions for magazines and rented a piano and gramophone (asking Edsel Ford to send along any old records). Because the first refugees moved in around Christmas the Perry’s purchased a Christmas tree, decorations, and small gifts for the children.

By 1918, because of war rationing, Perry was forced to reduce the number of refugees in the home and stop taking in new refugees; he proposed to the Fords to gradually start winding up the project and close down Oughtrington Hall. The chapel, priest, and doctor had all left by this time and Perry stated only families with children were left. Perry wrote Clara, “I feel that the conditions under which you have, for so long, rendered help to Belgian Refugees in this country, have materially changed; so much so, that it is probably true to say that there are no Belgian refugees in the same sense that there were three years ago.” He went on to add most of the refugees had found work and had become part of community, the others he believed should be taken care of by the government. Over the three years of operation a constant flow of hundreds of refugees came and went through Oughtrington Hall, the number of refugees fluctuated but appears to have stayed around 100 for the most part. Many found jobs, some at the Ford Manchester plant, and moved into homes of their own, or a relative in Belgium sent them money so they could establish their own residence. In July 1918, Perry transferred administration of the hall to the Manchester Belgian Refugees Committee along with the furniture and all equipment in the house.

Kathy Makas is Reference Archivist at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 1910s, Europe, World War I, philanthropy, Henry Ford, Ford Motor Company, by Kathy Makas

A Significant Car on an Important Roster

1927 Ford Model T Touring Car, The Fifteen-Millionth Ford. THF135450

Beginning today through April 9 we're honored to have our 1927 Ford Model T Touring Car, the fifteen-millionth Ford, on view at the National Mall for the 2018 Cars at the Capital event. The Historic Vehicle Association has selected our T for inclusion on its National Historic Vehicle Association Register. The 15 Millionth Model T joins impressive roster this year; other vehicles being added to the list include a 1984 Plymouth Voyager (the first Chrysler Minivan), a 1968 Ford Mustang Fastback (used in the iconic chase scene in the 1968 film Bullitt), a 1985 Modena Spyder California (featured in the 1986 movie Ferris Bueller's Day Off), and a 1918 Cadillac Type 57.

Henry Ford and Edsel Ford with the Fifteen-Millionth Ford Model T on the Last Day of Model T Production, May 26, 1927. THF118798

Although the 1927 Model T looked different from the original 1908 Model T due to many styling changes, the basic elements that made the Model T a technological innovation and cultural phenomenon - a simple 4-cylinder engine, planetary transmission, the limited color choices, and a flexible and strong chassis - were still there but were now liabilities in the automobile market. Consumers were no longer satisfied with a basic, dependable car. Americans demanded faster cars with smoother rides and more amenities. By the mid-1920s, it was obvious to almost everyone at Ford that the Model T's time had passed. Henry Ford, however, retained his firm belief that the Model T was all that anyone would ever need. In an attempt to check declining sales, Ford engineers incrementally modernized the car, introducing options such as electric starters, manually operated windshield wipers and body color choices. (Famously, black as the only color offered from 1914 through 1925.)

None of these ploys, however, allowed the Model T to compete with Chevrolet and Dodge Brothers cars that offered heaters, automated wipers, and a more comfortable ride - all at a comparable price.

When production of the Model T ended in May 1927, Henry Ford's "Universal Car" had introduced the world to the idea of personal mobility and transformed where and how we lived.

Take a look at the car getting ready to head to Washington, D.C., in this video.

cars, Greenfield Village, Henry Ford, by Matt Anderson, Ford Motor Company, Model Ts

Ford Radio and Fordlandia

Henry Ford used wireless radio to communicate within Ford Motor Company (FMC) starting after October 1, 1919. This revolutionary new means of communication captured Ford’s interest because it allowed him to transmit messages within his vast operation. By August 1920, he could convey directions from his yacht to administrators in FMC offices and production facilities in Dearborn and Northville, Michigan. By February 1922, Ford’s railroad offices and the plant in Flat Rock, Michigan were connected, and by 1925, the radio transmission equipment was on Ford’s Great Lake bulk haulers and ocean-going vessels. Historian David L. Lewis claimed that “Ford led all others in the use of intracompany radio communications” (The Public Image of Henry Ford, 311).

Ford Motor Company also used radio transmissions to reach external audiences through promotional campaigns. During 1922, FMC sales branches delivered a series of expositions that featured Ford automobiles and Fordson tractors. An article in Motor Age (August 10, 1922) described highlights of the four-month tour of western Oregon:

“The days are given over to field demonstrations of tractors, plows and implements, while at night a radio outfit that brings in the concerts from the distant cities and motion pictures from the Ford plant, keep an intensely interested crowd on the grounds until the Delco Light shuts down for the night.”

The Ford Radio and Film crew that broadcast to the Oregon crowds traveled in a well-marked vehicle, taking every opportunity available to inform passers-by of Ford’s investment in the new technology – radio – and the utility of new FMC products. Ray Johnson, who participated in the tour, recalled that he drove a vehicle during the day and then played dance music in the evenings as a member of the three-piece orchestra, “Sam Ness and his Royal Ragadours.”

Ford and Fordson Power Exposition Caravan and Radio Truck, Seaside, Oregon, 1922 . THF134998

In 1922, Intra-Ford transmissions began making public broadcasts over the Dearborn’s KDEN station (call letters WWI) at 250-watts of power, which carried a range of approximately 360 meters. The radio station building and transmission towers were located behind the Ford Engineering Laboratory, completed in 1924 at the intersection of Beech Street and Oakwood Boulevard in Dearborn.

Ford Motor Company Radio Station WWI, Dearborn, Michigan, March 1925. THF134748

Staff at the station, conveying intracompany information and compiled content for the public show which aired on Wednesday evenings.

Ford Motor Company Radio Station WWI, Dearborn, Michigan, August 1924. THF134754

The station did not grow because Ford did not want to join new radio networks. He discontinued broadcasting on WWI in early February 1926 (The Public Image of Henry Ford, 179).

Ford did not discontinue his intracompany radio communications. FMC used radio-telegraph means to communicate between the head office in Dearborn and remote locations, including, Fordlandia, a 2.5-million-acre plantation that Ford purchased in 1927 and that he planned to turn into a source of raw rubber to ease dependency on British colonies regulated by British trade policy.

Brazil and other countries in the Amazon of South American provided natural rubber to the world until the early twentieth century. The demand for tires for automobiles increased so quickly that South American harvests could not satisfy demand. Industrialists sought new sources. During the 1870s, a British man smuggled seeds out of Brazil, and by the late 1880s, British colonies, especially Ceylon (today Sri Lanka) and Malaysia, began producing natural rubber. Inexpensive labor, plus a climate suitable for production, and a growing number of trees created a viable replacement source for Brazilian rubber.

British trade policies, however, angered American industrialists who sought to establish production in other places including Africa and the Philippines. Henry Ford turned to Brazil, because of the incentives that the Brazilian government offered him. His goals to produce inexpensive rubber faced several hurdles, not the least of which was overcoming the traditional labor practices that had suited those who harvested rubber in local forests, and the length of time it took to cultivate new plants (not relying on local resources).

Ford built a production facility on the Tapajós River in Brazil. This included a radio station. The papers of E. L. Leibold, in The Henry Ford’s Benson Ford Research Center, include a map with a key that indicated the “proposed method of communication between Home Office and Ford Motor Company property on Rio Tapajos River Brazil.” The system included Western Union (WU) land wire from Detroit to New York, WU land wire and cable from New York to Para, Amazon River Cable Company river cable between Para and Santarem, and Ford Motor Company radio stations at each point between Santarem and the Ford Motor Company on Rio Tapajós. Manual relays had to occur at New York, Para, and Santarem.

Map Showing Routes of Communication between Dearborn, Michigan and Fordlandia, Brazil, circa 1928. THF134693

Ford officials studied the federal laws in Brazil that regulated radio and telegraph to ensure compliance. Construction of the power house and processing structures took time. The community and corporate facilities at Boa Vista (later Fordlandia) grew. By 1931, the power house had a generator that provided power throughout the Fordlandia complex.

Generator in Power House at Fordlandia, Brazil, 1931. THF134711

Power House and Water Tower at Fordlandia, Brazil, 1931. THF134714

Lines from the power house stretching up the hill from the river to the hospital and other buildings, including the radio power station. The setting on a higher elevation helped ensure the best reception for radio transmissions.

Sawmill and Power House at Fordlandia, Brazil, 1931. THF134717

Workers built the radio power house, which held a Delco Plant and storage batteries, and the radio transmitter station with its transmission tower. The intracompany radio station operated by 1929.

Radio Power House, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134697

Radio Transmitter House, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134699

Storage Batteries in Radio Power House, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134701

Delco Battery Charger for Radio Power House, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134703

Radio Power House Motor Generator Set, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134705

The radio power house is visible at the extreme left of a photograph showing the stone road leading to the hospital (on an even higher elevation) at Fordlandia.

Stone Road Leading to Hospital, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134709

Radio Transmitter Station, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134707

Back at FMC headquarters in Dearborn, Ford announced in late 1933 that he would sponsor a program on both NBC and CBS networks. The Waring show aired two times a week between 1934 and 1937, when Ford pulled funding. Ford also sponsored World Series broadcasts. The most important radio investment FMC made, however, was the Ford Sunday Evening Hour, launched in the fall of 1934. Eighty-six CBS stations broadcast the show. Programs included classical music and corporate messages delivered by William J. Cameron, and occasionally guest hosts. Ford Motor Company printed and sold transcripts of the weekly talks for a small fee.

On August 24, 1941 Linton Wells (1893-1976), a journalist and foreign correspondent, hosted the broadcast and presented a piece on Fordlandia.

Program, "Ford Summer Hour," Sunday, August 24, 1941. THF134690

Linton Wells was not a stranger to Henry Ford’s Greenfield Village, he and his wife, Fay Gillis Wells, posed for a tintype in the village studio on 2 May 1940.

Tintype Portrait of Linton Wells and Fay Gillis Wells, Taken at the Greenfield Village Tintype Studio, circa 1940. THF134720

This radio broadcast informed American listeners of the Fordlandia project, in its 16th year in 1941. Wells summarized the products made from rubber (by way of an introduction to the importance of the subject). He described the approach Ford took to carve an American factory out of an Amazonian jungle, and the “never-say-quit” attitude that prompted Ford to re-evaluate Fordlandia, and to trade 1,375 square miles of Fordlandia for an equal amount of land on Rio Tapajós, closer to the Amazon port of Santarem. This new location became Belterra. Little did listeners know the challenges that arose as Brazilians tried to sustain their rubber production, and Ford sought to grow its own rubber supply.

By 1942, nearly 3.6 million trees were growing at Fordlandia, but the first harvest yielded only 750 tons of rubber. By 1945, FMC sold the holdings to the Brazilian government (The Public Image of Henry Ford, 165).

The Ford Evening Hour Radio broadcasts likewise ceased production in 1942 after eight years and 400 performances.

Learn more about Fordlandia in our Digital Collections.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment; Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communication and Information Technology; and Jim Orr is Image Services Specialist at The Henry Ford.

Sources

- Relevant collections in the Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford, Dearborn, Michigan.

- Grandin, Greg. Fordlandia: The Rise and Fall of Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City. Picador. 2010.

- Lewis, David L. The Public Image of Henry Ford: An American Folk Hero and His Company. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 1976.

- Frank, Zephyr and Aldo Musacchio. “The International Natural Rubber Market, 1870-1930.″ EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. March 16, 2008.

South America, 20th century, 1940s, 1930s, 1920s, technology, radio, Michigan, Henry Ford, Fordlandia and Belterra, Ford Motor Company, communication, by Kristen Gallerneaux, by Jim Orr, by Debra A. Reid

Seventy-five Years of the George Washington Carver Cabin

This year, we celebrate the 75th anniversary of the dedication of the George Washington Carver Memorial in Greenfield Village. There is not a great deal of specific information about this project in the archival collections, but here is what we do know.

Henry Ford’s connections and interest in the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute began as early as 1910 when he contributed to the school’s scholarship fund. At this time, George Washington Carver was the head of the Research and Experimental Station there.

Henry Ford always had interests in agricultural science, and as his empire grew, he became even more focused on using natural resources, especially plants, to maximize industrial production. He was especially interested in plant materials that could be grown locally. Carver has similar interest, but his focus was on improving the lives of southern farmers. His greatest fame was that of a “Food Scientist”, though he was also very well known for developing a variety of cotton that was better suited for the growing conditions in Alabama. Through the decades that followed, connections and correspondences were made, but it would not be until 1937 that the two would meet face to face.

Through the 1930s, work and research began to really ramp up in the Research or Soybean Laboratory in Greenfield Village. Various plants with the potential to produce industrial products were researched, but eventually, the soybean became the focus. Processes that extracted oils and fibers became very sophisticated, and some limited production of soy based car parts did take place in the late 1930s and early 1940s, as a result of the work done there.

In 1935, the Farm Chemurgic Council had its very first meeting in Dearborn. This group, formed to study and encourage better use of renewable resources, would meet annually becoming the National Farm Chemurgic Council. It was at the 1937 meeting, also held in Dearborn, that George Washington Carver, and his assistant, Austin Curtis, were asked to speak. Carver was put up in a suite of rooms at the Dearborn Inn, and it was here that he and Henry Ford were able to meet and discuss their ideas for the first time, face to face. During the visit, Ford entertained Carver at Greenfield Village and gave him the grand tour. Carver was also invited to address the students of the Edison Institute Schools. Carver would write to Ford following the visit, “two of the greatest things that have come into my life have come this year. The first was the meeting with you, and to see the great educational project that you are carrying on in a way that I have never seen demonstrated before.”

It was at some point during the visit that Henry Ford put forth the idea of including a building dedicated to George Washington Carver in Greenfield Village. It seems that he asked Carver about his recollections of his birthplace, and went as far as to ask for descriptions and drawings. Later correspondence from Austin Curtis in November of 1937 confirm Ford’s interest. It was determined by that point that the original building that stood on the farm of Moses Carver in Diamond Point, Missouri had long been demolished. Granting Ford’s request, Curtis would go on to supply suggested dimensions and a sketch, to help guide the project. The cabin was described as fourteen feet by eighteen feet with a nine- foot wall, reaching to fourteen feet at the peak of the roof. It included a chimney made of clay and sticks.

A 1937 rendering of the birthplace of George Washington Carver based on his recollections. No artist is attributed, but it is likely this was drawn by Carver. THF113849

It would not be until the spring of 1942 that the project would get underway. The building, very loosely based on the descriptions provided by Carver, would be constructed adjacent to the Logan County Courthouse. In 1935, the two brick slave quarters from the Hermitage Plantation, had been reconstructed on the other side of the courthouse. The grouping was completed with the addition of the Mattox House (thought to be a white overseers house from Georgia) in 1943. As Edward Cutler, Henry Ford’s architect, would state in a 1955 interview, “we had the slave huts, the Lincoln Courthouse, the George Washington Carver House. The emancipator was in between the slaves and the highly- educated man, It’s a little picture in itself.”

There are no records beyond Henry Ford’s requests for information as to how the final design of the building, that now stands in Greenfield Village, was determined. An invoice and correspondence does appear requesting white pine logs, of specific dimensions, from Ford’s Iron Mountain property. There is also an extensive photo documentation of the construction process in the spring and early summer of 1942.

Foundation being set, spring 1942. THF28591

Beginnings of the framing, Spring 1942. THF285293

Logs in place, roof framing in process, spring 1942. THF285285

Newly Completed George Washington Carver Memorial, Early Summer, 1942. THF285295

In the end, the cabin would resemble less of a hard scrabble slave hut, and more of a 1940s Adirondack style cabin that any of us would be proud to have on some property “up north”. It was fitted out with a sitting room, two small bedrooms (with built in bunks), a bathroom, and a tiny kitchen. It was furnished with pre-civil war antiques and was also equipped with a brick fireplace that included a complete set-up for fireplace cooking. As an interesting tribute to Carver, a project, sponsored by the Boy Scouts of America, provided wood representing trees from all 48 states and the District of Columbia to be used as paneling throughout the cabin. Today, one can still see the names of each wood and state inscribed into the panels.

Plans had initially been made for Carver to come for an extended stay in Dearborn in August of 1942, but those plans changed and he arrived on July 19. This was likely due to Carver’s frail health and bouts of illness. While the memorial was being built, extensive plans were also underway for the conversion of the old Waterworks building on Michigan Avenue, adjacent to Greenfield Village, into a research laboratory for Carver. The unplanned early arrival date forced a massive effort into place to finish the work before Carver arrival. Despite wartime restrictions, three hundred men were assigned to the job and it was finished in about a week’s time.

George Washington Carver would stay for two weeks and during his visit, he was given the “royal” treatment. His visit was covered extensively by the press and he made at least one formal presentation to the student of the Edison Institute at the Martha Mary Chapel. During his stay, he resided at the Dearborn Inn, but on July 21, following the dedication of the laboratory and the memorial in Greenfield Village, just to add another level of authenticity to the cabin, Carver spent the night in it.

George Washington Carver and Henry Ford at the Dedication of the George Washington Carver National Laboratory, July 21, 1942. THF253993

Edsel Ford, George Washington Carver, and Henry Ford, Carver Memorial, July 21, 1942. THF253989

George Washington Carver at fireplace in Carver Memorial, July 21, 1942. THF285303

George Washington Carver seated at the table in Carver Memorial, July 21, 1942. THF285305

Interior views of Carver Memorial, August, 1943. THF285309 and THF285307

The completed George Washington Carver Memorial in Greenfield Village c.1943. THF285299

Beginning in 1938, Carver began to suffer from some serious health issues. Pernicious anemia is often a fatal disease and when first diagnosed, there was not much hope for Carver’s survival. He surprised everyone by responding to the new treatments and gaining back his strength. Henry and Clara visited Tuskegee in 1938 for the first time, later, when Henry Ford heard of Carver’s illness, he sent an elevator to be installed in the laboratory where Carver spent most of his time. Carver would profusely thank Ford, calling it a “life saver”. In 1939, Carver visited the Fords at Richmond Hill and visited the school the Fords had built and named for him there. In 1941, the Fords made another visit to Tuskegee to attend the dedication of the George Washington Carver Museum.

During this time, Carver would suffer relapses, and then rebound, each time surprising his doctors. This likely had much to do with his change in travel plans in the summer of 1942. Following his visit to Dearborn, through the fall, there was regular correspondence to Henry Ford. One of the last, dated December 22, 1942, was a thank you for the pair of shoes made by the Greenfield Village cobbler. Following a fall down some stairs, George Washington Carver died on January 5, 1943, he was seventy-eight years old.

Carver Memorial in its whitewashed iteration, c.1950. THF285299

It was seventy-five years ago, that George Washington Carver made his last trip to Dearborn. His legacy lives on here, and he remains in the excellent company of those everyday Americans such as Thomas Edison, the Wright Brothers, and Henry Ford, who despite very ordinary beginnings, went on to achieve extraordinary things and inspire others. His fame lives on today, and even our elementary school- age guests, know of George Washington Carver and his work with the peanut.

Jim Johnson is Curator of Historic Structures and Landscapes at The Henry Ford.

Sources Cited

- Bryan, Ford, Friends, Family & Forays: Scenes from the Life & Times of Henry Ford, Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 2002.

- Edward Cutler Oral Interview, 1955, Archival Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- Collection of correspondences between Henry Ford and George Washington Carver, Frank Campsall, Austin Curtis, 1937-1943, Archival Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- George Washington Carver Memorial Building Boxes, Archival Collection, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford.

- The Herald, August, 1942, The Edison Institute, Dearborn, MI

Dearborn, Michigan, farms and farming, agriculture, Henry Ford, by Jim Johnson, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, George Washington Carver, African American history

The Logan County Courthouse Story

As we look forward to the Greenfield Village opening of 2017, our guests and staff alike enjoy reconnecting with our amazing array of historic buildings. Each of them not only represent different periods of American history, they also hold so many fascinating stories. Among the more interesting, are how they came to have new lives here in Greenfield Village. The Logan County Courthouse’s story is among my favorites.

Abraham Lincoln featured prominently in Henry Ford’s plans for Greenfield Village which revolved around the story of how everyday people with humble beginnings would go on to play important roles in American history. Henry Ford was a “later comer” to the Lincoln collecting world, but with significant resources at his disposal, he did manage to secure a few very important items. The Logan County Courthouse is among them. Logan County Courthouse as it stands today in Greenfield Village.

Logan County Courthouse as it stands today in Greenfield Village.

Authenticated objects, related to Lincoln’s early life, were especially scarce by the late 1920s.There seemed to be an abundance of items supposedly associated and attributed to Lincoln, especially split rails and things made from them. But very few of these were the real thing. For Henry Ford, the idea of acquiring an actual building directly tied to Abraham Lincoln seemed unlikely.  Logan County Courthouse September of 1929.

Logan County Courthouse September of 1929.

But, in the summer of 1929, through a local connection, Henry Ford was made aware that the old 1840 Postville/ Logan County, Illinois courthouse, where Lincoln practiced law, was available for sale. The 89-year-old building, was used as a rented private dwelling, and was in run down condition, described by some as “derelict”. It was owned by the elderly Judge Timothy Beach and his wife. They were fully aware of the building’s storied history, and had made several unsuccessful attempts to turn the historic building over to Logan County in return for funding the restoration, and taking over its on-going care and maintenance. View of rear section of building with shed addition, September 1929

View of rear section of building with shed addition, September 1929

Seeing no other options, the Beaches agreed to the sale of the building to Henry Ford via one of his agents. They initially seemed unaware of Henry Ford intentions to move the building to Greenfield Village, assuming it was to be restored on-site much like another historic properties Ford had taken over. The local newspaper, The Courier, even quoted Mrs. Beach as saying “she would refund to Mr. Ford if it was his plan to take the building away from Lincoln, as nothing was said by the agent about removal”. By late August of 1929, the entire project in West Lincoln, Illinois, had captured the national spotlight and the old courthouse suddenly had garnered a huge amount of attention, even becoming a tourist destination.

View of side currently adjacent to Dr. Howard’s Office, September, 1929. This view shows evidence of filled in window openings. The window currently behind the judge’s bench was restored.

View of side currently adjacent to Dr. Howard’s Office, September, 1929. This view shows evidence of filled in window openings. The window currently behind the judge’s bench was restored.

By early September, local resistance to its removal was growing, and Henry Ford felt the need to pay a visit to personally inspect the building and meet with local officials, and the Beaches. He clearly made his case with the owners and finalized the deal. As reported, “Ford sympathized with the sentiment of the community but thought that the citizens should look at the matter from a broader viewpoint. He spoke for the cooperation of the community with him in making a perpetual memorial for the town at Dearborn, where the world would witness it. My only desire is to square my own conscience with what I think will be for the greatest good to the greatest number of people.”

Views of partitioned first floor, summer 1929.

The courthouse would indeed be leaving West Lincoln, and by September 6, Henry Ford’s crew arrived to begin the process of study, dismantling, and packing for the trip to Dearborn. Local resistance to the move continued as the final paperwork was filed, and the newly purchased land was secured by Ford’s staff. By September 11, the resistance had run its course and the dismantling process began. It was also revealed that the city, county, several local organizations, and even the state of Illinois had all been offered several opportunities to acquire the building and take actions to preserve it. They all had declined the various offers over the years. It was then understood that Judge & Mrs. Beach, in the end, had acted on what was best for the historic building and should not be “subjected to criticism.” Judge Beach would die a week later, on September 19th.

The dismantling and discovery process was closely covered by the local newspapers, and as the building came apart, its original design was revealed.

Beginning as early as the late 1840s, changes had taken place on both the exterior and interior of the building. By 1880, the building had been converted from a commercial building into a dwelling and that was the state in which it was found by Ford’s crew in 1929. The doorway and first floor interior had been radically changed and eventually, a covered porch was added to what is now the main entrance, and a shed addition to the rear. But, the most significant change, was the move off its original foundation, 86 feet forward on the lot.

In 1848, the county seat moved from Postville, to Mount Pulaski. At that time the courthouse was decommissioned, and after a legal battle between the County, and the original investor/builders of the building, it was sold to Solomon Kahn. None other than Abraham Lincoln successfully represented the County in the matter. Mr. Kahn converted the building into a general store, and ran the local post office within. It was he who moved the building to its new location. In doing so, the old limestone foundation was left behind, and the original limestone chimney and interior fireplaces were demolished. A new brick lined cellar and foundation was created, along with updated internal brick chimneys on each end of the building, designed to accommodate cast-iron heating stoves. This took place before 1850.

The oldest know photograph of the Logan County Courthouse c.1850-1880. The original door arrangement remains in place.

The oldest know photograph of the Logan County Courthouse c.1850-1880. The original door arrangement remains in place.

Photographs taken in September of 1929, show the outline of the original chimney on the side of the building where it has been re-created today. Further discoveries revealed the original floor plan of a large single room on the first-floor, and the original framing for the room divisions on the second. Second floor photographs show the original wall studs, baseboards, chair rails, window, and door frames, all directly attached to the framing, with lath and plaster added after the fact. The framing of the walls on the first floor were all clearly added after the original build. The oldest photograph of the courthouse shows it on its second site with its original window and door arrangement still in place, but with new brick chimneys. The photo dates from between 1850 and 1880.

It was some of the older inhabitants of the area that alerted Henry Ford’s staff as to the original location of the foundation. Once located, the original foundation revealed the dimensions of the original first-floor fireplace. All the stones were carefully removed and shipped to Dearborn. The courthouse rests on this foundation today. The local newspaper also reported that while excavating the foundation, a large key and doorknob were found at the edge, aligned where the front door would have been located.

View of side that currently faces Scotch Settlement School, September, 1929. Shadow of original stone chimney is visible. Patched sections of siding show that originally, the stone would have been flush with the siding until approximately the top third, which would have extended out from the building like the entire chimney currently does. The window and door are late additions.

View of side that currently faces Scotch Settlement School, September, 1929. Shadow of original stone chimney is visible. Patched sections of siding show that originally, the stone would have been flush with the siding until approximately the top third, which would have extended out from the building like the entire chimney currently does. The window and door are late additions.

By September 20th, the building, consisting of two car loads of material, was on its way to Dearborn. Reconstruction in Greenfield Village began almost immediately at a frenzied pace. Finishing touches were still being applied right up until the October 21st dedication of Greenfield Village. Edward Cutler oversaw the final design elements needed to restore the building along with the actual work of reconstructing it. All the first- floor details, including the fireplace, mantle, and judges bench had to be re-created. The first-floor interior trim was reproduced in walnut, and was based on the original trim that survived on the second floor. The second floor, using a large amount of original material, including flooring, was also restored to its original appearance. Even the original plaster was collected, re-ground, and used to re-plaster the interior walls.

Views of the excavated original foundation, located 86 feet back from building’s second location. Lower view shows foundation for the original fireplace. September, 1929.

Views of the excavated original foundation, located 86 feet back from building’s second location. Lower view shows foundation for the original fireplace. September, 1929.

Based on the oldest of the original photographs, all new windows and exterior doors were also reproduced. Where possible, the original exterior walnut siding was also restored, and re-applied to the building and secured with brass screws.This was not a period technique, but rather a solution by Cutler to ensure the original siding with its worn nail holes, would stay in place.

The result was a place where Henry Ford could now display, and share his collection of Lincoln associated artifacts, including the most famous of all, the rocking chair from the presidential booth in Ford’s theater where Abraham Lincoln was sitting when he was shot by John Wilkes Booth in April of 1865.

Re-construction well under way in Greenfield Village on October, 2, 1929. The building would be complete for the October 21, dedication. The Sarah Jordan Boarding House can be seen in the distance.

Re-construction well under way in Greenfield Village on October, 2, 1929. The building would be complete for the October 21, dedication. The Sarah Jordan Boarding House can be seen in the distance.

The completed Logan County Courthouse in Greenfield Village as it appeared for the October 21 dedication.

The completed Logan County Courthouse in Greenfield Village as it appeared for the October 21 dedication.

The newly unpacked Ford’s Theater rocking chair in the Logan County Courthouse, January of 1930.

The interior of the completed Logan County Courthouse c.1935. It featured a display of Abraham Lincoln associated objects including Springfield furniture and the rocking chair from Ford’s Theater.

The interior of the completed Logan County Courthouse c.1935. It featured a display of Abraham Lincoln associated objects including Springfield furniture and the rocking chair from Ford’s Theater.

From 1929 until the mid-1980s, the building was left almost untouched as a shrine to Abraham Lincoln.

It was not until the mid-1980s that the research material was re-examined, primarily for preparations for much needed repairs to the now 50 plus year old restoration. In 1980, prior to the restoration work, the Lincoln assassination rocking chair was removed from the courthouse and placed in Henry Ford Museum. In 1984, the building underwent a significant restoration and was re-sided, the first- floor flooring was repaired, and extensive plaster repair and refinishing took place. In addition, a furnace was added (inside the judge’s bench), to provide adequate heat.

The interpretation of the building also was redefined and was re-focused away from the Abraham Lincoln shrine and more toward the stories of the history of our legal system and the civic lives of Americans in the 1840s. Gradually, many of the Lincoln artifacts were removed to appropriate climate controlled storage or display in Henry Ford Museum.

That brings us to the Greenfield Village opening of 2017. The Logan County Courthouse has now stood as long in Greenfield Village as it did in Postville, 88 years. It has had an interesting and storied history in both locations. Both the curatorial team, and the Greenfield Village programs team are excited to continue the process of ongoing research and improving the scholarship of the stories we tell there. We are working on some projects to accomplish just that for the near future and are looking forward to sharing all the details.

Continue ReadingHenry Ford, Michigan, Dearborn, Illinois, 20th century, 19th century, presidents, Logan County Courthouse, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, by Jim Johnson, Abraham Lincoln

The Search for Home

Detroit Reacts to the Great Migration: Before the first World War, a majority of Detroit's African American population lived on the East Side and shared the area, known as Black Bottom, with white immigrant populations. At this time, relatively few African Americans, just 1.2% of the total population, called Detroit home. By 1930, the city’s African American population had grown by over 1,991%. The white immigrant population began to vacate the Black Bottom area and were quickly replaced with the growing population of African Americans attracted to the north by the promise of employment in Detroit’s booming auto industry and an escape from the rampant oppression of the south. As the African American population in Detroit increased, racial residential boundaries began to form, due in part to the stress on housing stock, as well as to outright discrimination in institutions such as employment and real estate.

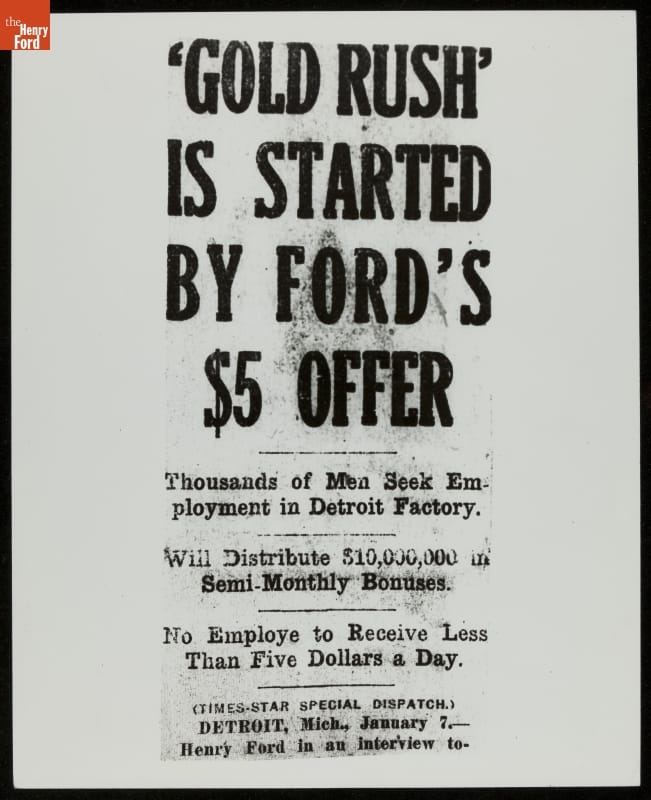

Photographic print - "Newspaper Article, "Gold Rush is Started by Ford's $5 Offer," January 7, 1914" - Ford Motor Company

The automobile industry and Henry Ford’s highly-publicized $5-a-day helped to draw people in great numbers to the Detroit area. However, for African American workers, reality often differed from their hopes and expectations in the north. While many of the automotive manufacturers did hire African Americans, it was almost always for the lowest paying jobs, such as in the janitorial department or the foundry. Ford Motor Company led the automotive industry in its hiring of African American workers by 1919. The company paid African American workers the same rate as their white counterparts and hired for a variety of positions, including skilled labor. Across the board, however, African American workers made less money than their white counterparts, and consequently, had less income for quality housing.

Photographic print - "Pickling Metal Crankcases and Other Parts to Remove Surface Impurities, Ford Rouge Plant, 1936" - Ford Motor Company Photographic Department

Discriminatory real estate practices played a significant role in the housing issues which plagued Detroit. Racially restrictive covenants, which legally ensured the sale of property to only white buyers, became increasingly common in Detroit. Even if a restrictive covenant was not in place, the Detroit Real Estate Board warned area realtors “not to sell to Negroes in a 100 percent white area,” thereby enforcing and perpetuating Detroit’s racial geography. Further, the practice of “redlining,” or the racial categorization of areas by their perceived financial risk in home insurance and mortgage lending, effectively shut out black homebuyers from the market. The practice extended to the lending of new mortgages, but also to home loans, leading to the inability to complete home repairs and, eventually, an abundance of blighted homes in black neighborhoods. In addition, real estate agents erroneously reported to white homeowners that the presence of black families in their neighborhoods would lower their property values. White homeowners, even those without ingrained prejudices against African Americans, certainly did not want their property values to lower, so rallied against any attempt by an African American homebuyer purchasing in their neighborhoods. The infamous story of African American Physician Dr. Ossian Sweet exemplifies the discrimination and mob violence experienced by those who attempted to move into white neighborhoods.

Discrimination in the workplace meant that African Americans, as a whole, made significantly less money than their white counterparts. Redlining practices forced them into racially-segregated neighborhoods and cemented their inability to access loans for mortgages or home repairs. Yet, the promise of the north continued to draw African Americans to Detroit. Without access to capital, increasingly-crowded neighborhoods became increasingly-deteriorated. At each turn, discriminatory systems excluded an entire population from quality housing. From these conditions, Charles H. Lawrence and his family departed Detroit in search of quality housing and a better life. He became the first African American to settle in Inkster, Michigan, and hundreds soon followed.

African Americans Settle in Inkster

The City of Inkster, also located in Wayne County, is approximately fourteen miles from downtown Detroit. Detroit Urban League President John Dancy fielded many housing inquiries from frustrated African American migrants to Detroit in the post-World War I period and beyond. Unable to locate sufficient housing in the City of Detroit, Dancy broadened his search outside the City with hopes that more rural areas would not have the same restrictive covenants and that lesser demand would persuade landowners to sell to African American buyers. In 1920, Dancy succeeded when he found amenable property owners in possession of 140 acres in rural Inkster. Although Inkster’s first African American residents’ settlement in Inkster preceded Dancy’s discovery, the 140 acres of available land enabled and impelled hundreds more African American families to move from Detroit to Inkster, despite the lack of a local government or basic public amenities like streetlights or sewer lines.

Clipping (Information artifact) - ""Henry Ford on Unemployment," 1932" - Detroit Free Press (Firm)

A Community Becomes a Project

Henry Ford was vocal about his disdain for institutionalized philanthropy. He wrote an entire chapter, entitled “Why Charity?” in an autobiography, and explained, “philanthropy, no matter how noble its motive, does not make for self-reliance…A philanthropy that spends its time and money in helping the world to do more for itself is far better than the sort which merely gives and thus encourages idleness.” Henry Ford’s brand of philanthropy was characterized by helping people help themselves. During the Great Depression, Henry Ford was called upon by the City of Detroit to provide aid because the City’s welfare offices were overwhelmed. Their argument, aside from civic responsibility, was that the City was not receiving taxes from Ford Motor Company (FMC’s factories were located outside Detroit) yet as many as “36 percent of the families receiving care from the City of Detroit were former Ford employees” in 1931. The public goodwill that Ford’s $5 a day policy brought was quickly dissipating. In 1931, Ford agreed to two philanthropic ventures; he provided a low-interest, short-term $5 million loan to the City of Detroit and essentially took the then-Village of Inkster under the Ford Motor Company’s auspices.

Photographic print - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

Photographic print - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

Photographic print - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

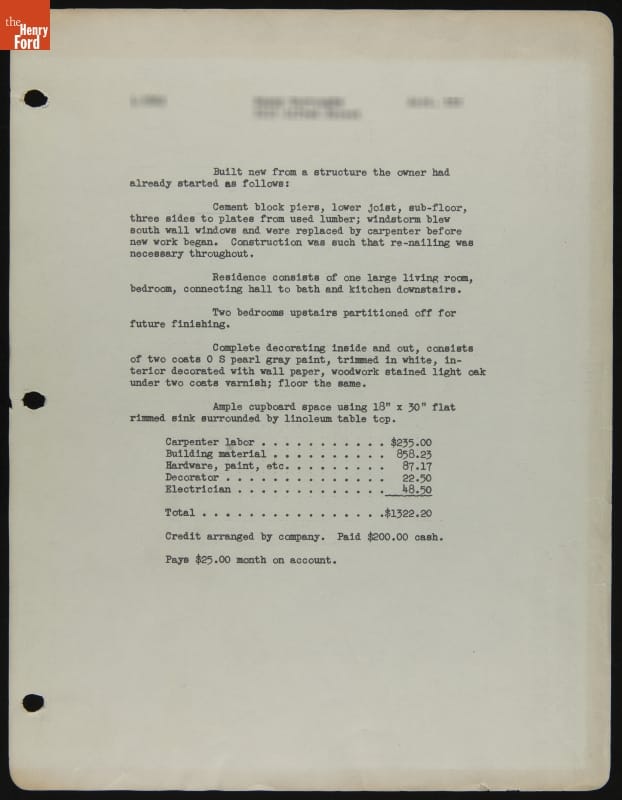

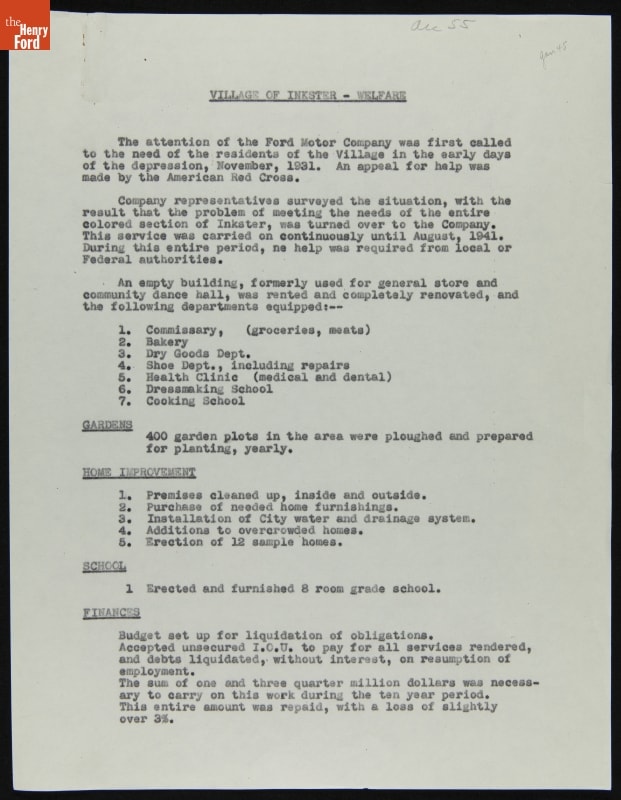

Report - "Ford Motor Company Employee Home Improvement Project, Inkster, Michigan, 1930-1944" - Ford Motor Company

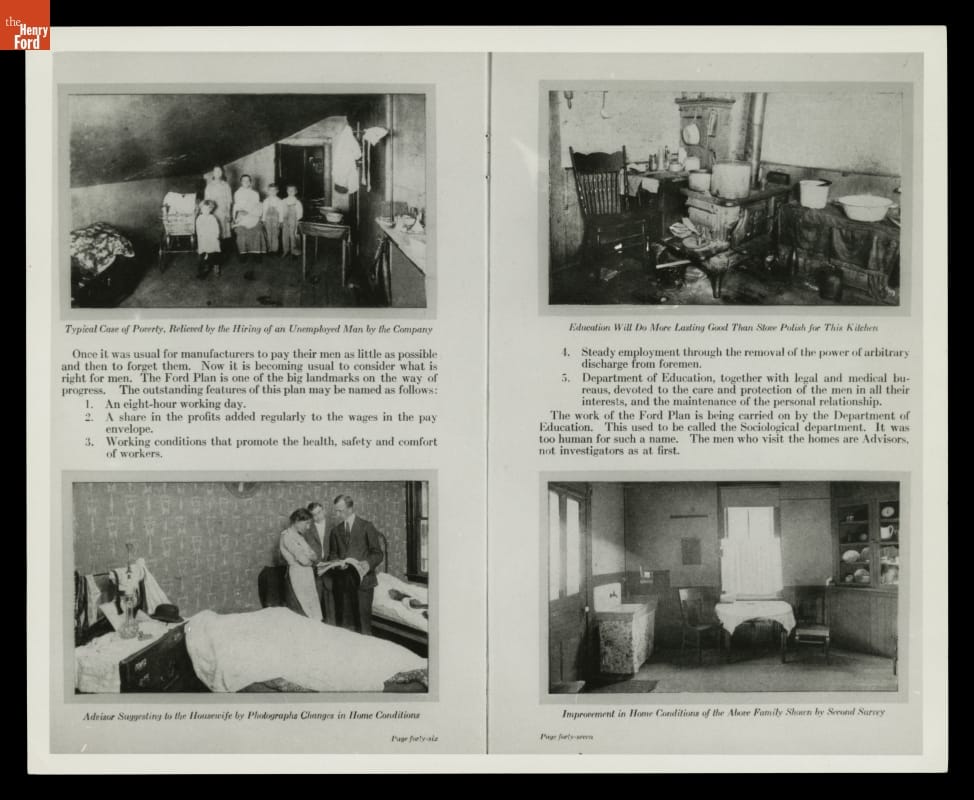

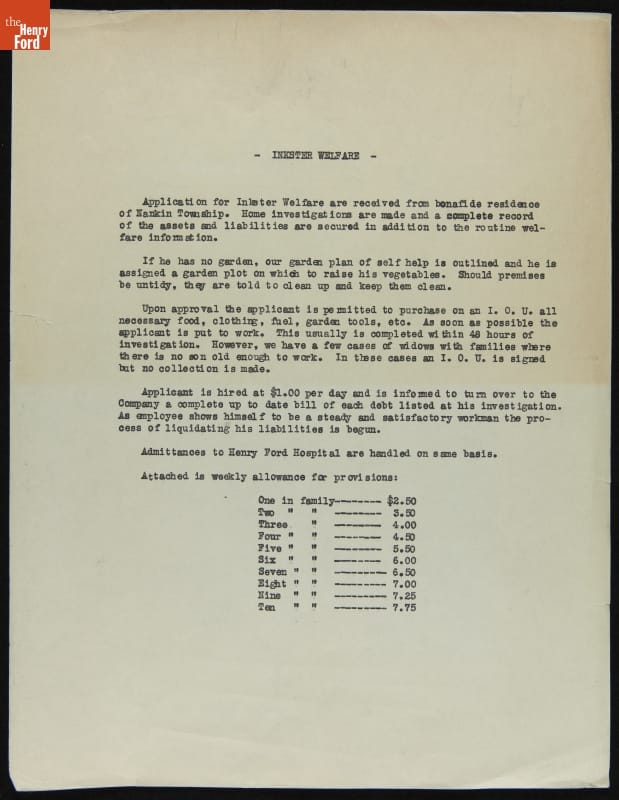

By 1931, a few years into the Great Depression’s hardships, the residents of Inkster were struggling. Unemployment and debt were high, public services had been cut, and many residences remained partially-completed, as the Great Depression halted progress in the young village. Controversially, Henry Ford placed FMC’s Sociological Department in charge of what became known as the Inkster Project. The Sociological Department was created in 1914 in order to manage the diverse workforce and ensure employee adherence to the company’s strict standards, which were paternalistic in nature and often crossed the home life-work life boundary. In Inkster, the Sociological Department immediately began implementing programs to comprehensively rehabilitate the village. A commissary, which sold high-quality, low-cost food and essential home goods, was established. Coal was distributed to those who needed it to heat their homes. Debtors were paid off, and a medical clinic and school were constructed. Homes deemed insufficient were rehabilitated. The inability to pay for these services was irrelevant; a type of “I.O.U,” repayable through Ford-provided work and wages, was enough to access all life’s necessities.

Photographic print - "Checking on Ford Employees Home Conditions, Views from "Factory Facts From Ford," 1917"

The Legacy of the Inkster Project

Although the Inkster Project was generally highly-regarded at the time, the FMC Sociological Department’s role was often overreaching. When agreeing to Ford’s aid, an Inkster resident was also agreeing to running their household as preferred by Henry Ford. Although his funds undoubtedly helped Inkster during the Great Depression, Ford’s motives were not entirely altruistic. Besides the much-needed public relations boost he received from the Inkster Project, he also was able to assert his influence and ideals on a community that largely had no choice but to accept his aid -- with all strings attached.

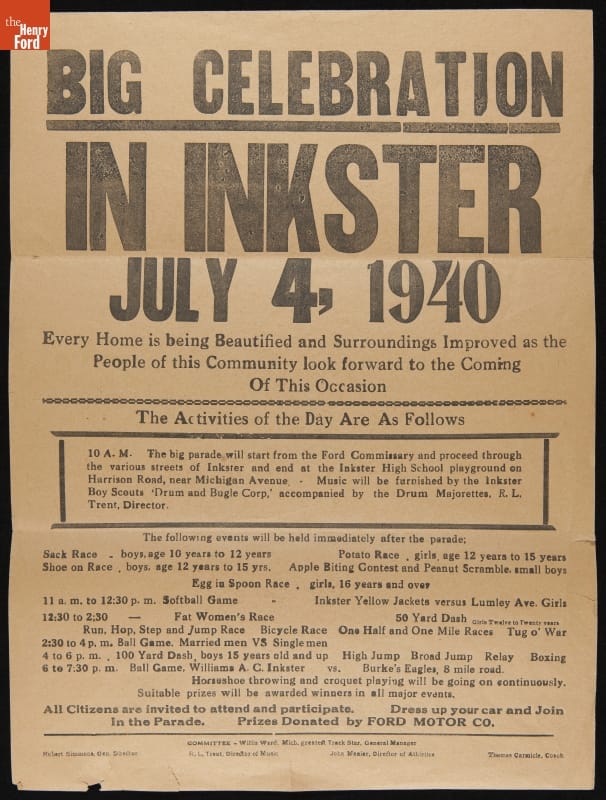

Broadside (Notice) - "Big Celebration in Inkster," July 4, 1940"

The Inkster Project’s legacy is complicated; many historians criticize Henry Ford’s paternalistic nature and the perhaps forceful imposition of his will onto the desperate, but others, including former residents of Inkster, praise Henry Ford for his aid. In her reminiscences, Georgia Ruth McKay explains that Inkster became a “jungle village changed into a city” during this period and that, “without his [Henry Ford’s] help, many would not have survived.” The Inkster Project was slowly phased out, but continued to operate in Inkster until 1941 when all programs were withdrawn.

Progress report - "Village of Inkster Welfare Report, 1931-1941" - Ford Motor Company

Report - "Village of Inkster Welfare Provision Report, circa 1936" - Ford Motor Company

Katherine White is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. In writing this piece, she appreciated the research and writings of Beth Tompkins Bates’ “The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford”, Thomas J. Sugrue’s “The Origins of the Urban Crisis; Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit,”, and Howard O’Dell Lindsey’s dissertation, “Fields to Fords, Feds to Franchise: African American Empowerment in Inkster, Michigan.”

20th century, Michigan, labor relations, home life, Henry Ford, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, Detroit, by Katherine White, African American history

Starting and Ending with Henry

Some time ago, The Henry Ford’s digitization team started a project to digitize selected photographs of Greenfield Village buildings. More than 2800 photos and two years later, we have finally completed this project, a celebration marked by the team with mini-cupcakes and commemorative coasters featuring some of our favorite images from the project.

While all the buildings have a strong relationship to Henry Ford—the majority were selected by him and added to the Village under his watch—the final building we imaged is one of the most important to Henry’s story: his birthplace. We imaged over 175 photos of Ford Home, including this November 5, 1920 shot of the house on its original site.

Visit our Digital Collections and search on any building name to see more—or see some staff favorite photos in our Expert Set.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, Henry Ford, by Ellice Engdahl, digital collections

Celebrating Manufacturing Day

Every year, the first Friday in October brings Manufacturing Day, a time to celebrate the contribution that modern manufacturing makes to our lives. We see it not only in the countless products we use every day, but in the many jobs that manufacturing provides to American workers.

We thought it would be appropriate to mark the day with a look back at the most influential manufacturing innovation of the 20th century: Henry Ford’s moving assembly line. By combining interchangeable parts with the subdivision of labor and the movement of work to workers, Ford dramatically increased the speed with which his employees built Model T automobiles – reducing the car’s price and boosting sales as a result. The moving assembly line quickly spread to other automakers, and then to manufacturers of all types. Today, almost anything you can name is made on an assembly line, from helicopters to hamburgers.

Here, in honor of Manufacturing Day, is an Expert Set of 25 photos, documents and artifacts that tell the story of Henry Ford’s ground-breaking manufacturing technique.

Henry Ford: Assembly Line

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

by Matt Anderson, Ford Motor Company, Henry Ford, cars, manufacturing

An Educator Admired by Henry Ford

We are closing in on the end of our multi-year project to digitize photographs related to the buildings in Greenfield Village, and one of the most recent buildings we’ve tackled has been the William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace. In the 1830s, McGuffey created a series of textbooks commonly known as McGuffey’s Readers, intended to teach reading and writing to various grade levels of schoolchildren. Henry Ford used these readers as a child and considered them an important influence in his life, so he moved the Washington County, Pennsylvania birthplace of McGuffey to Greenfield Village in the early 1930s, dedicating it on September 23, 1934, the 134th anniversary of the author’s birth. Among the several dozen images we’ve just digitized is this 1845 portrait of Harriet Spining McGuffey, who became William Holmes McGuffey’s wife in 1827.

Visit our Digital Collections to view all of the newly digitized images, or browse through other McGuffey-related artifacts, including a number of McGuffey Readers.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Henry Ford, Pennsylvania, 19th century, 1830s, William Holmes McGuffey Birthplace, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, education, digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl, books