Posts Tagged manufacturing

The Wool Carding Machine

THF621302

Few pieces of textile technology had as great an impact for as long a time as the wool carding machine. The wool industry was much slower to mechanize than the cotton textile industry, for several reasons: the longer time it took to perfect wool processing machines; the fact that the machines were not engineered to work together for efficient production; and the conviction by potential entrepreneurs that it was impossible to compete with fine British imports and, as a result, wool processing did not offer the same potential for profit as cotton textiles. The slow mechanization of the wool industry both reinforced and encouraged the already strong tradition of home production of wool through the 19th century.

Before carding machines, farm families prepared wool for spinning using hand cards like these. / THF183701

Despite—and partially because of—the slow mechanization of the wool industry, carding machines thrived. The first machines to be perfected in the wool production process, carding machines accomplished the one step that was most significant—and most tedious—in preparing wool before spinning. Mechanized carding machines not only sped up the time and removed the tedium of hand-carding, but they also produced a better combed roll of wool for spinning—improving both spinning time and the ultimate quality of the spun yarn.

The carding machine, introduced in America during the 1790s, was based upon technology and know-how brought by immigrant British machinists. It was adopted quickly in America. By 1810, there were 1,776 new carding machines in the US, duplicating the action of hand cards.

Manufacturers of carding equipment emerged to supply the growing wool industry in the 19th century. / Detail, THF621405

In the typical carding mill, sheared wool was first sent through a picker to remove dirt and separate hard bunches of wool. The teeth on the rotating cylinder of the mechanical picker replaced the previous similar hand process of opening the wool fibers, cleaning out the dirt, burrs, and other impurities, then fluffing the wool.

When first shorn, sheep’s wool is matted, waxy, and dirty. / THF119199

After picking, wool is fed into the carding machine. / THF91532 (Photographed by John Sobczak)

Like the picker, the carding machine also transferred an earlier hand process into a more efficient rotary operation. Using several toothed leather strips (called card clothing) fixed on a series of revolving cylinders, it opened and blended the wool into a series of uniform sheets of fiber, shaping these sheets of fiber into loose, fluffy rolls called rovings. The cylinders were arranged so the ends of the teeth were nearly in contact, allowing for the continuous shaping of each roving, ready for spinning. Each roving, produced across the width of the carding machine, had a common length of 24 inches—ideal for hand spinning. It was longer, narrower, and ultimately sturdier, than those formed with hand cards.

Carding machines produced loose rolls of wool fiber, called rovings, ready to be spun into yarn on wool wheels like this one. / THF175844

Because carding machines mechanized the laborious hand process of straightening and combing wool fibers—an important step in preparing yarn and making woolen cloth—carding mills (like John Gunsolly’s 1850s mill, now in Greenfield Village), became extremely popular in 19th-century America. To learn more about how families embraced mechanized carding, watch for another upcoming blog post.

Donna Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

"Sampling" the Past: Fabrics from America's Textile Mills

In 2017, The Henry Ford acquired a significant collection of materials from the American Textile History Museum (ATHM) when financial challenges forced that organization to close its doors. Founded in 1960, ATHM was located in Lowell, Massachusetts, a city key to the story of the Industrial Revolution and to the American textile industry. For decades, ATHM gathered and interpreted a superb collection of textile machinery and tools, clothing and textiles, and an extensive collection of archival materials. The Henry Ford was among the many museums, libraries, and other organizations to which ATHM's collections were transferred.

The Henry Ford acquired textile machinery, clothing, and textiles, as well as archival material that includes approximately 3,000 cubic feet of printed materials and fabric samples from various textile manufacturers, dating from the early 1800s into the mid-to-late 1900s. As part of the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship, The Henry Ford has digitized many sample books, as well as product literature, from the archival material within the ATHM collection.

So, what is a sample book? Textile manufacturing companies – commonly referred to as mills or print works – kept a record of fabrics produced by the company within a given year or season. These records typically consist of a fabric sample attached to a blank page in a bound book, and are often accompanied by information including pattern name, inventory number, dyestuffs, and in a few cases, the retail company for which the fabric was made.

The pages of these books offer a rich look at the broad range of fabrics produced by an increasingly mechanized textile industry, allowing researchers to see the evolution in textile design, materials, and manufacturing techniques. They also allow a glimpse into the various methods of recordkeeping among the many companies represented in the collection. Finally, the books—and the fabric samples within them—provide us with a broad view into the rich color palate of American textiles of the 1800s and 1900s. This is especially helpful for exploring clothing and textiles in the era before widespread color photography, where our understanding of the period is dulled by black-and-white depictions. The sample books are strikingly beautiful, offering an intriguing glimpse of the evolution of styles and patterns over time.

In addition to the sample books, we had the opportunity to digitize several examples of product literature from the 1900s, including catalogs and brochures. The product literature was used for marketing and sales, rather than as a record of production. These materials offer insight into the fabric and designs available for clothing or domestic use during the 1900s.

Have I piqued your interest? Below are a few favorite items I’ve come across in this collection.

Sample Books

Cocheco Manufacturing Company (Dover, New Hampshire & Lawrence, Massachusetts)

Fabric Samples from the Notebook of Washington Anderton, Color Mixer for Cocheco Print Works, 1876-1877 / THF670738, THF670787, THF670757

Fabric Samples from the Notebook of Washington Anderton, Color Mixer for Cocheco Print Works, November to December 1877 / THF670668, THF670707, THF670697

Sample Book, January 9, 1880 to April 22, 1880 / THF600226

Hamilton Manufacturing Company (Lowell, Massachusetts)

Sample Book, April 9, 1900 to May 27, 1901 / THF600027, THF600141, THF600167

Lancaster Mills (Clinton, Massachusetts)

Sample Book, "36 Inch Klinton Fancies," Fall 1927 / THF299907, THF299924

Sample Book, "Glenkirk," Spring 1928 / THF299970, THF299971

Product Literature

Hellwig Silk Dyeing Company (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

Sample Book, "Indanthrene Colors," 1900-1920 / THF299990

Montgomery Ward & Co. (Chicago, Illinois)

Suit Catalog, "Made to Measure All Wool Suits," 1932 / THF600534

I.V. Sedler Company, Inc. (Cincinnati, Ohio)

Catalog, "The Nation's Stylists Present Sedler Frocks," 1934 / THF600502

Carlton Mills, Inc. (New York, New York)

Sales Catalog for Men's Fashion, 1940-1950 / THF670587

Harford Frocks, Inc. (Cincinnati, Ohio)

"Frocks by Harford Frocks, Inc.," 1949 / THF600604

Sears, Roebuck and Company (Chicago, Illinois)

"Sears Decorating Made Easy," 1964 / THF600561

Samantha Johnson is Project Curator for the William Davidson Foundation Initiative for Entrepreneurship at The Henry Ford. Special thanks to Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford for sharing her expertise of the textile industry and for reviewing this content.

20th century, 19th century, manufacturing, furnishings, fashion, entrepreneurship, by Samantha Johnson

The Jazz Bowl: Emblem of a City, Icon of an Age

The Jazz Bowl, originally called The New Yorker, about 1930. THF88363

Cowan Pottery of Rocky River, Ohio, was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy in early 1930 when a commission arrived from a New York gallery for a New York City-themed punch bowl. The client -- who preferred to remain unknown -- wanted the design to capture the essence of the vibrant city.

The assignment went to 24-year-old ceramic artist Viktor Schreckengost. His design would become an icon of America’s “Jazz Age” of the 1920s and 1930s.

The Artist and His Design

The cosmopolitan Viktor Schreckengost was a perfect choice for this special commission. Schreckengost (1906-2008), born in Sebring, Ohio, had studied ceramics at the Cleveland Institute of Art in the late 1920s. He then spent a year in Vienna, where he was introduced to cutting-edge ideas in European art and design. When Schreckengost returned to Ohio, he took a part-time teaching position at his alma mater and spent the balance of his time as a designer at Cowan Pottery.

A jazz musician as well as an artist, Schreckengost had firsthand knowledge of New York, where he frequented jazz clubs during visits. To Schreckengost, jazz music represented the spirit of New York. He wanted to capture its excitement and energy in visual form on his bowl. Schreckengost later recalled: “I thought back to a magical night when a friend and I went to see [Cab] Calloway at the Cotton Club [in Harlem] ... the city, the jazz, the Cotton Club, everything ... I knew I had to get it all on the bowl.”

During its heyday in the 1920s and 30s, the Cotton Club was the place to listen to jazz in New York. THF125266

A “Jazz”-inscribed drumhead surrounded by musical instruments symbolize the Cotton Club. Organ pipes represent the grand theater organs that graced New York City’s movie palaces during the 1920s and 1930s. Schreckengost recalled that he was especially fond of Radio City Music Hall’s Wurlitzer organ. THF88363

A show in progress at Radio City Music Hall auditorium, 1936. THF125259

The images on the Jazz Bowl, then, may be read as a night on the town in New York City, starting out in bustling Times Square; then on to Radio City Music Hall to enjoy a show; next, a stroll uptown past a group of soaring skyscrapers to take in a sweeping view of the Hudson River; afterward, a stop at a cocktail party; and finally--topping off the evening with a visit to the famous Cotton Club.

Times Square, circa 1930. THF125262i

The blinking traffic signals, and "Follies" and "Dance" signs on the Jazz Bowl portray the vitality of Times Square at night. THF88358

Schreckengost decorated the punch bowl with a deep turquoise blue background he described as “Egyptian,” since it recalled the shade found on ancient Egyptian pottery. According to Schreckengost, the penetrating blue immerses the viewer in the glow of the night air--and the sensation of mystery and magic of a night on the town.

This is the view of the New York skyline and the Hudson River that Schreckengost saw on his trips to the city and later interpreted in the Jazz Bowl. THF125264g

Skyscrapers, a luxury ocean liner, cocktails on a tray, and liquor bottles represent a night on the town. THF88364

The Famous Client

In early 1931, the finished bowl was delivered to New York. The pleased patron who had commissioned it immediately ordered two additional punch bowls. To Schreckengost’s delight, the patron turned out to be Eleanor Roosevelt, then First Lady of New York State. Mrs. Roosevelt had commissioned the bowl to celebrate her husband Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1930 reelection as governor. She presumably placed one bowl in the Governor’s Residence in Albany, one in the Roosevelts’ home in Hyde Park, and one in their Manhattan apartment. When the Roosevelts moved into the White House in 1933, after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s election as President, one of the bowls made its way there as well.

Eleanor Roosevelt commissioned the Jazz Bowl to celebrate her husband’s 1930 reelection as governor of New York. THF208655

Mass Producing the Jazz Bowl?

Immediately after the Jazz Bowl was delivered to Eleanor Roosevelt, the New York City gallery placed an order for fifty identical bowls. Unfortunately, Schreckengost’s process was laborious--it took Cowan Pottery’s artisans an entire day to produce the incised decoration on Mrs. Roosevelt’s version. Cowan Pottery sought to mass produce the punch bowl, simplifying the original design to create a second and third version the company originally marketed as “The New Yorker.”

The Henry Ford’s bowl is the third version, known informally as “The Poor Man’s Jazz Bowl.” It is slightly smaller than the original and the decoration is raised, rather than scratched into the surface. No one knows exactly, but perhaps fifty of the original version, only a few of the unsuccessful second version, and possibly twenty of the third version of the Jazz Bowl were made in total. The whereabouts of many of the Jazz Bowls are not known, though they appear periodically on the art market and are acquired by eager collectors. Even the present location of the bowls made for Eleanor Roosevelt seems to be a mystery.

Jazz Bowl as Icon

The “Poor Man’s Jazz Bowl” didn’t save the Cowan Pottery from the ravages of the Great Depression -- by the end of 1931, the company folded. Viktor Schreckengost moved on, continuing to teach at the Cleveland Institute of Art and pursuing freelance design for several firms. His Jazz Bowl would come to be recognized as a visual icon of the Jazz Age in America.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. This post originally ran as part of our Pic of the Month series.

New York, 20th century, 1930s, 1920s, presidents, music, manufacturing, making, Henry Ford Museum, furnishings, decorative arts, by Charles Sable, art

The Henry Ford’s Ingersoll Milling Machine and Mass Production at Highland Park

THF129649

What are the icons of the Industrial Revolution—steam engines, printing presses, combine harvesters, textile machinery? Any such list would surely include Ford’s Model T. Like the other machines that would make the grade it too was a complex mechanism, but it was also a beloved consumer product rooted in personal practical everyday use, and it was a design icon—in its day a symbol of absolute modernity.

The T’s success came about through two revolutions within the Industrial Revolution—those of power generation and distribution, and precision production manufacturing. Developments in the electrical industry liberated Henry Ford and his production experts from the constraints of mechanical power distribution. Earlier systems dictated where machinery was placed based on long straight runs of shafts and associated pulleys. Electric motors powering first groups and then individual machines enabled Ford’s engineers to position machine tools where the production process dictated. It was the incredible machines developed specifically for that process that were crucial to the speed and quality of Model T production.

Henry Ford and his assistants developed a system of mass production at Ford Motor Company’s Highland Park plant that was based on moving components through a refined sequence of manufacturing, machining and assembly steps. Launched in October 1913, Ford’s new system ultimately reduced the time of producing Model Ts from about 12½ man-hours to only 1½ man-hours.

Model Ts contained more than ten thousand parts. Ford’s moving assembly line required that each one of these parts be manufactured to exacting tolerances (the acceptable amount of variation) and be fully interchangeable with any other part of its kind. By organizing the automobile’s construction into a series of distinct small steps and using precision machinery, the assembly line generated enormous gains in productivity.

This is the only survivor of the vast range of custom-designed high-production machine tools used at Ford’s Highland Park plant. THF129616

Machines like this 1912 Ingersoll milling machine were crucial to the high production levels attained at Highland Park. Milling machines are machine tools that rotate cutters to plane or shape surfaces. Teams of Ford specialists collaborated with machine tool designers to develop and continually improve machinery for Highland Park, resulting in milling machines that were capable of undertaking highly accurate, multiple cutting operations on many components at the same time.

One of six similar machines in a careful arrangement of machine tools in Highland Park’s cylinder finishing shop, this planer-type milling machine – both a vertical and a horizontal miller – simultaneously milled the underside and main bearing holders of Model T engine blocks. Cutters on the horizontal spindle shaped the bearing holders, while large cutters on vertical spindles milled the bottom surface of the blocks flat. The machine could mill 15 engine blocks in one batch—loaded and unloaded by semi-skilled labor. The work was physically demanding, and while it did not demand the skills of a trained machinist, it did require dexterity and attention to detail in addition to stamina.

The Henry Ford’s Ingersoll milling machine is represented by one of the six horizontal cross shapes labeled #2 on the left of this diagram, which shows the arrangement of machine tools in the cylinder block machining shop at Highland Park. THF300582

The Ingersoll milling machine first arrived at Ford’s Highland Park plant in December 1912. It was just one of a vast range of new, specialized machines that enabled Ford to mass produce quality, affordable vehicles – and capture 50% of the American market! Today, it is exhibited in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation as the only survivor of the custom-designed high-production machine tools used at Highland Park. Twenty-one feet long and eight feet high, the machine is an imposing presence and a compelling reminder of Ford’s moving assembly line—as important a development as the Model T itself.

Additional Readings:

- Steam Engine Lubricator, 1882- “Female Operatives Are Preferred”: Two Stories of Women in Manufacturing

- The Changing Nature of Sewing

- Collecting Mobility: Insights from Hagerty

cars, Ford Motor Company, Made in America, Henry Ford Museum, Model Ts, manufacturing

#InnovationNation: Agriculture & Environment

cars, Greenfield Village buildings, manufacturing, farms and farming, Greenfield Village, farm animals, farming equipment, The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation, agriculture

#InnovationNation: Design & Making

Take a look at a collection of clips showcasing design and making within the collections at The Henry Ford.

technology, African American history, quilts, fashion, manufacturing, Henry Ford Museum, Eames, The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation, making, design

A Closer Look: The Champion Egg Case Maker

After the Civil War, urban populations swelled. Until this time, farm families had kept flocks of chickens and gathered eggs for their own consumption, but with increased demand for eggs in growing cities, egg farming grew into a specialized industry. Some families expanded egg production at existing farms, and other entrepreneurs established large-scale egg farms near cities and on railroad lines. Networks developed for shipping eggs from farms to buyers – whether wholesalers, retailers, or individuals operating eating establishments.

While farmers who sold eggs directly to customers carried their products to market in different ways, sellers who shipped eggs to buyers standardized their containers to ensure a consistent product. The standard egg case became an essential and enduring part of the egg industry.

Egg producers initially used different sizes and types of containers to pack eggs for market. As the egg industry developed, standardized cases that held thirty dozen (360) eggs – like this version first patented by J.L. and G.W. Stevens in 1867 – became the norm. THF277733

Egg distributors settled on a lightweight wooden box to hold 30 dozen (360) eggs. The standard case had two compartments that held a total of twelve “flats” – pressed paper trays that held 30 eggs each and provided padding between layers. Retailers who purchased wholesale cases of eggs typically repackaged them for sale by the dozen (though customers interested in larger quantities could – and still can – buy flats of 30 eggs).

The standard egg case held 12 of these pressed paper trays, or “flats,” which held 30 eggs each. THF169534

Some egg shippers purchased premade egg cases from dedicated manufacturers. Others made their own. Enter James K. Ashley, who invented a machine to help people build egg cases to standard specifications. Ashley, a Civil War veteran, first patented his egg case maker in 1896 and received additional patents for improvements to the machine in 1902 and 1925.

James K. Ashley’s patented Champion Egg Case Maker expedited the assembly of standard egg cases.

Ashley’s machine, which he marketed as the Champion Egg Case Maker, featured three vises, which held two of the sides and the interior divider of the egg case steady. Using a treadle, the operator could rotate them, making it easy to nail together the remaining sides, bottom, and top to complete a standard egg case, ready to be stenciled with the seller’s name and filled with flats of eggs for shipment.

Ashley’s first customer was William Frederick Priebe, who, along with his brother-in-law Fred Simater, operated one of the country’s largest poultry and egg shipping businesses. As James Ashley continued to manufacture his egg case machines (first in Illinois, then in Kentucky) in the early twentieth century, William Priebe found rising success as the big business of egg shipping grew ever bigger.

One of James K. Ashley’s Champion Egg Case Makers, now in the collections of The Henry Ford. THF169525

James Ashley received some acclaim for his invention. Ashley’s Champion Egg Case Maker earned a medal (and, reputedly, the high praise of judges) at the St. Louis World's Exposition in 1904. And in 1908, The Egg Reporter – an egg trade publication that Ashley advertised in for more than a decade – described him as “the pioneer in the egg case machine business” (“Pioneer in His Line,” The Egg Reporter, Vol. 14, No. 6, p 77).

While the machine in the The Henry Ford’s collection no longer manufactures egg cases, it still has purpose – as a keeper of personal stories and a reminder of the complex ways agricultural systems respond to changes in where we live and what we eat.

Additional Readings:

- Henry’s Assembly Line: Make, Build, Engineer

- Ford’s Game-Changing V-8 Engine

- Steam Engine Lubricator, 1882

- The Wool Carding Machine

farming equipment, manufacturing, food, farms and farming, farm animals, by Saige Jedele, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture

The Tucker 48: “The Car You Have Been Waiting For”

The 1948 Tucker

The Tucker '48 automobile, brainchild of Preston Thomas Tucker and designed by renowned stylist Alex Tremulis, represents one of the most colorful attempts by an independent car maker to break into the high-volume car business. Ultimately, the Big Three would continue to dominate for the next forty years. Preston Tucker was one of the most recognized figures of the late 1940s, as controversial and enigmatic as his namesake automobile. His car was hailed as "the first completely new car in fifty years." Indeed, the advertising promised that it was "the car you have been waiting for." Yet many less complimentary critics saw the car as a fraud and a pipe dream. The Tucker's many innovations were and continue to be surrounded by controversy. Failing before it had a chance to succeed, it died amid bad press and financial scandal after only 51 units were assembled.

Much of the appeal of the Tucker automobile was the man behind it. Six feet tall and always well-dressed, Preston Tucker had an almost manic enthusiasm for the automobile. Born September 21, 1903, in Capac, Michigan, Preston Thomas Tucker spent his childhood around mechanics' garages and used car lots. He worked as an office boy at Cadillac, a policeman in Lincoln Park, and even worked for a time at Ford Motor Company. After attending Cass Technical School in Detroit, Tucker turned to salesmanship, first for Studebaker, then Stutz, Chrysler, and finally as regional manager for Pierce-Arrow.

As a salesman, Tucker crossed paths at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway with the great engine designer Harry A. Miller, and in 1935 they formed Miller-Tucker, Inc. Their first contract was to build race cars for Henry Ford. The company delivered ten Miller-Ford Indy race cars, but they proved inadequate for Ford and he pulled out of the project.

During World War II, automobile companies' operations were dedicated to the war effort. Denied new car models for four years, by the war's end Americans were eager for a new automobile, any new automobile. The time was right for Tucker to begin his dream. In 1946, he formed Tucker Corporation for the manufacture of automobiles.

Tucker Corporation employee badge. THF135737

He set his sights on the old Dodge plant in the Chicago suburb of Cicero, Illinois. Spanning over 475 acres, the plant built B-29 engines during World War II, and its main building, covering 93 acres, was at the time the world's largest under one roof. The War Assets Administration (WAA) leased Tucker the plant provided he could have $15 million dollars capital by March 1 of the following year. In July, Tucker moved in and used any available space to build his prototype while the WAA inventoried the plant and its equipment.

The fledgling company needed immediate money, and Tucker soon discovered that support from businessmen who could underwrite such a venture meant sacrificing some, if not all, control of his company. To Tucker, this was not an option, so he conceived of a clever alternative. He began selling dealer franchises and soon raised $6 million dollars to be held in escrow until his car was delivered. The franchises attracted the attention of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and in September of 1946 it began an investigation, the first of a series that would last for the next three years.

The agreements were rewritten to SEC satisfaction and the franchise sales proceeded. In October, Tucker began another proposal: a $20 million stock issue contingent upon a completed prototype and clearance by the SEC. That same month, Tucker met his first serious obstacle. Wilson Wyatt, head of the National Housing Agency, ordered the WAA to cancel Tucker's lease and turn the plant over to the Lustron Corporation to build prefabricated houses.

Tucker may have been an unfortunate pawn in a bureaucratic war between the housing agency and the WAA, but the battle continued until January of 1947. Franchise sales fell, stock issues were delayed, and Tucker's reputation was severely damaged. In the end, he kept his plant, but the episode made him some real enemies in Washington, including Michigan Senator Homer Ferguson. But Tucker did find some allies. The WAA extended Tucker's $15 million cash deadline to July 1 and Senator George Malone of Nevada began his own investigation of the SEC.

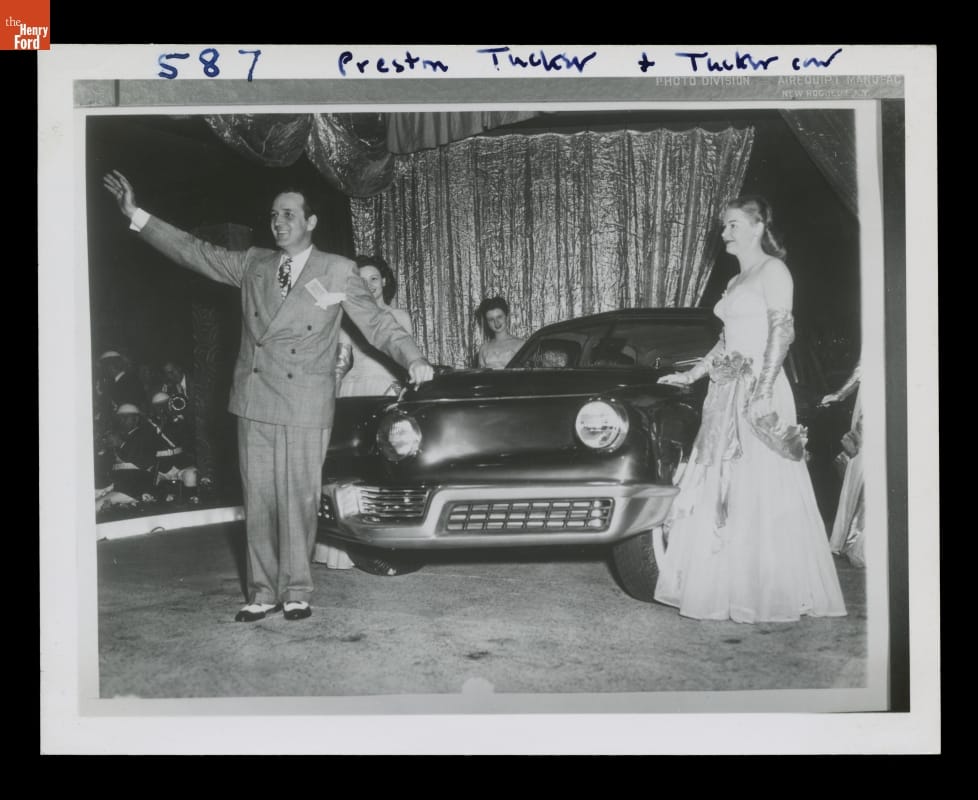

Meanwhile, Tucker still had a prototype to build. During Christmas 1946, he commissioned Alex Tremulis to design his car and ordered the prototype ready in 100 days. The time frame was unheard of, but necessary. Unable to obtain clay for a mock-up, engineers – many from the race car industry – began beating out sheet iron, a ridiculous way to build a car but a phenomenal achievement. The first car, completely hand-made, was affectionately dubbed the "Tin Goose." Preston Tucker unveils his car, June 19, 1947. THF135047

Preston Tucker unveils his car, June 19, 1947. THF135047

The Tucker '48 premiered June 19, 1947, in the Tucker plant before the press, dealers, distributors and brokers. Tucker later discarded many of the Tin Goose's features, such as 24-volt electrical system starters to turn over the massive 589-cubic-inch engine. For the premier, workers substituted two 12-volt truck batteries weighing over 150 pounds that caused the Tucker's suspension arms to snap. Speeches dragged on as workers behind the curtain tried feverishly to get the Tin Goose up and running. Finally, before the crowd of 5000, the curtains parted and the Tucker automobile rolled down the ramp from the stage and to its viewing area where it remained for the rest of the evening. Stock finally cleared for sale on July 15.

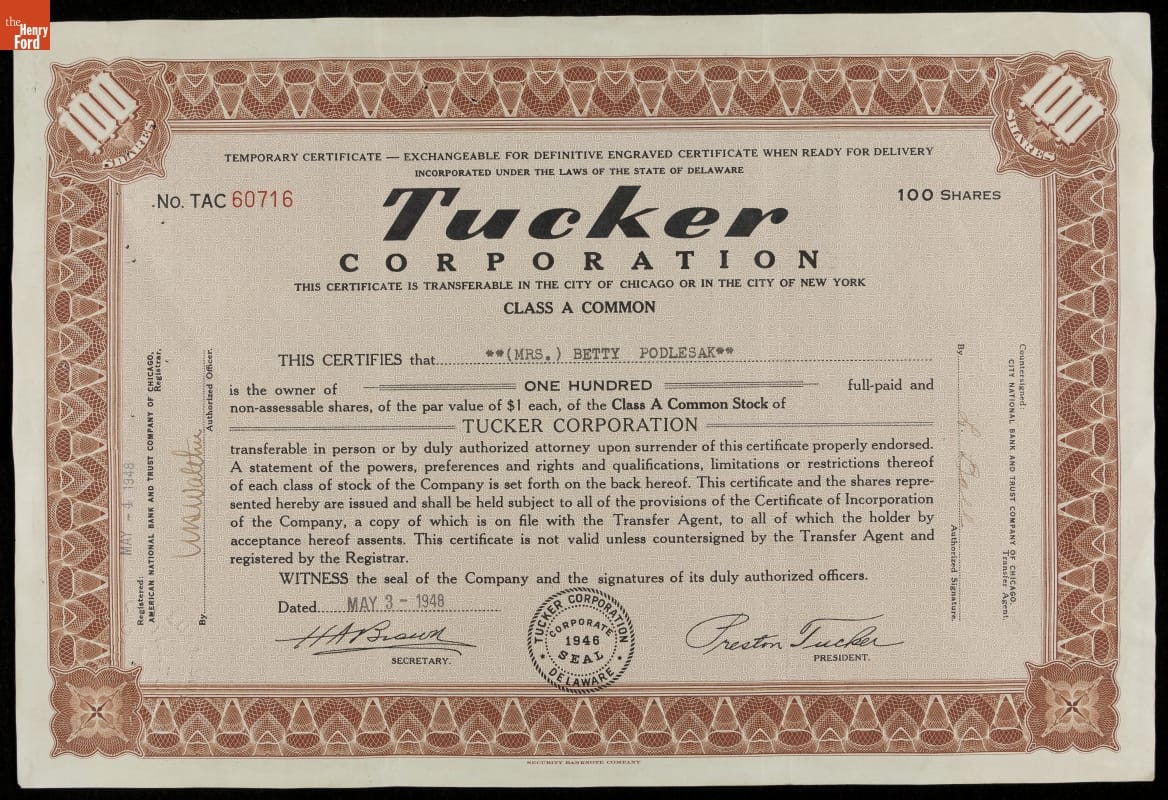

By the spring of 1948, Tucker had a pilot production line set up but his stock issue had been $5 million short and he again needed immediate money. He began a pre-purchase plan for Tucker automobile accessories such as radios and seat covers. Although he raised $1 million, advanced payment on accessories to a car not yet in production was the final straw for the SEC. On May 28, 1948, the SEC and the Justice Department launched a full-scale investigation. Investigators swarmed the plant and Tucker was forced to stop production and lay off 1,600 workers. Receivership and bankruptcy suits piled up, creditors bolted, and stock plunged. A Tucker stock certificate for 100 shares, dated May 3, 1948. THF208633

A Tucker stock certificate for 100 shares, dated May 3, 1948. THF208633

The SEC's case had to show that the Tucker car could not be built, or – if built – would not perform as advertised. But Tucker was building cars. Seven Tuckers performed beautifully at speed trials in Indianapolis that November, consistently making 90 mph lap speed. However, after Thanksgiving, a skeletal crew of workers assembled the last cars that the company would ever produce. In January 1949, the plant closed and the company was put under trusteeship.

"Gigantic Tucker Fraud Charged in SEC Report" ran the Detroit News headline in March. The article related an SEC report recommending conspiracy and fraud charges against Preston Tucker. Incensed, Tucker demanded to know how the newspaper had seen the report even before him. SEC Commissioner John McDonald later admitted he delivered the report to the paper in direct violation of the law. Feeling tried and convicted by the press, Tucker wrote an open letter to many newspapers around the country.

On June 10, Tucker and seven of his associates faced a Grand Jury indictment on 31 counts – 25 for mail fraud, 5 for SEC regulation violation, and one on conspiracy to defraud. The trial opened on October 5, 1949, and from the beginning the prosecution based its entire case on the "Tin Goose" prototype. It refused to recognize the 50 production cars and called witness after witness who, under cross-examination, ended up hurting the government's case. In the end, Tucker's defense team merely stated that the government had failed to prove any offense so there was nothing to defend.

On January 22, 1950, the jury found the defendants innocent of any attempt to defraud, but the verdict was a small triumph. The company was already lost. The remaining assets, including the Tucker automobiles, were sold for 18 cents on the dollar. Seeking some recompense, Preston Tucker filed a series of civil suits against news organizations that he believed had defamed him in the months leading up to his trial. His targets included the Detroit News, which he hit with a $3 million libel suit in March 1950.

In preparation for its defense, the Evening News Association – publisher of the Detroit News – acquired Tucker serial number 1016 for examination. But the suit never reached the courtroom. Preston Tucker was diagnosed with lung cancer and died December 26, 1956. The Evening News Association subsequently presented car 1016 to The Henry Ford, where it remains today.

Illinois, Michigan, 20th century, 1940s, manufacturing, entrepreneurship, cars

Positioning and Synchronicity on Paper

THF91558 (Photographed by John Sobczak)

In the early 19th century, lined paper was generally used only in business ledgers and account books. And the ruling was done by hand using cylindrical rulers and dip pens. Imagine the tedious hours that went into ruling just one book, with multiple colored lines as well as many stop lines, cross lines and sets of double as well as single lines.

In the 1840s, William Orville Hickok got to work on improving this by-hand paper-ruling process, inventing a machine that had a moving belt running beneath a set of pen nibs held in place by a crossbar. Cotton threads, dipped into a trough of ink containers, kept the overhead pens moist. Ink was applied from the mounted pens to the paper fed through the machine — an exercise in perfect positioning and synchronicity.

Learn more about William Orville Hickok and his contributions to the paper-ruling business, and see the 1913 Hickok Paper Ruling Machine for yourself in Made in America at Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. The Hickok paper-ruling machine was donated by Carl H. Dubac of Saginaw, Michigan, in 1986. Dubac’s father, who bound books by hand for more than 60 years, used the machine to line paper for ledger books.

Additional Readings:

- Made in America: Manufacturing- Thomas Blanchard’s Wood Copying Lathe

- Women in Industry and at Home in WWI

- The Wool Carding Machine

making, manufacturing, communication, Henry Ford Museum, Made in America

Ford Ambulances for the Red Cross

Ford Motor Company devoted its employees and manufacturing facilities to military production during both of the 20th century’s world wars. Ford’s efforts in World War I were slow to start, given Henry Ford’s outspoken opposition to the conflict, but once the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, the automaker rose to the challenge. Over the next two years, Ford built passenger cars, supply trucks, aircraft engines, gun caissons, tanks, helmets and body armor. Ironically, one of Ford’s best-known wartime products, the Eagle anti-submarine boats, never saw action before the Armistice. However, the factory that built the Eagle boats subsequently became the core of Ford’s River Rouge plant.

Ford’s efforts for World War II were greater still. Like other American automakers, the company suspended all civilian production in February 1942. Ford famously turned out B-24 bombers at its Willow Run facility, but it also produced a variety of wheeled vehicles including jeeps, amphibious cars, armored cars, trucks and tanks. Ford’s non-vehicle production included military gear of every type, from aircraft engines to guns to helmets to tents.

Red Cross Workers with a Ford Military Ambulance at the Highland Park Plant, 1918. THF 263442

Needless to say, ambulances were among the most crucial vehicles used in both wars. During World War I, Ford personal collaborated with the United States Surgeon General’s Office and frontline drivers to design a Model T-based ambulance ideal for battlefield conditions. The company donated $500,000 to the Red Cross, enabling the humanitarian organization to purchase nearly 1,000 vehicles for wartime use – including 107 ambulances. Beyond those Red Cross units, another 5,745 ambulances were built for the Allied armies.

Red Cross Motor Corps members took classes in auto maintenance. These women are checking under a Ford ambulance’s hood in 1942. THF 265816

Dodge produced most of the frontline ambulances used by American forces in World War II, but Ford units were active on the homefront. The Red Cross’s Motor Corps, established in World War I, rendered important service during the Second World War as well. Corps drivers working in the United States ferried Red Cross staff and supplies, couriered packages and messages, and occasionally stepped in to assist with Army and Navy transportation needs. An estimated 45,000 women were active in the Motor Corps during World War II. Corps members generally drove their personnel vehicles in this service, but Ford-built ambulances were also used in the transport of the sick and wounded.

In honor of National Red Cross Month, take a look at our digital collections to see more artifacts related to the organization.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

manufacturing, 1940s, 1910s, 20th century, World War II, World War I, healthcare, Ford Motor Company, cars, by Matt Anderson