Posts Tagged michigan

Searching for Structural Integrity

One of the key aspects of the Dymaxion House in Henry Ford Museum is its central mast, which supports the entire structure. Buckminster Fuller, who created Dymaxion, had a lifelong interest in creating maximal structural strength with minimal materials and weight, most famously seen in his work with geodesic domes. When Fuller won his first commission for a geodesic structure, the Ford Rotunda, he worked with the Aerospace Engineering Lab at the University of Michigan to create a truss for load testing. Saved twice from being discarded by university staff, this test module was donated to The Henry Ford in 1993.

It’s newly digitized and available for viewing in our Digital Collections, along with many other artifacts related to geodesic domes, Buckminster Fuller, and the Dymaxion House.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

design, Michigan, Dearborn, Ford Motor Company, engineering, Buckminster Fuller, by Ellice Engdahl, digital collections

Join the Industrial Revolution... Workshop

The Henry Ford proudly announces that the National Endowment for the Humanities has awarded our institution a grant to again offer the Landmarks of American History and Culture Workshop “America’s Industrial Revolution at The Henry Ford” for K-12 teachers. The workshops will be held July 9-14, 2017 and July 16-21, 2017.

Participating teachers will explore the varied ways that Americans experienced social change between 1760s and the 1920s through lecture/discussions by noted scholars and by visiting select sites at The Henry Ford, Greenfield Village and Henry Ford Museum, including Thomas Edison’s Menlo Park Laboratory, working farms, historic transportation, and Ford Motor Company’s Rouge industrial complex. In addition, participants will explore archival sources in the Benson Ford Research Center and dedicate time to lesson plan development with colleagues.

“Learning by doing” - Scything, pre-Industrial Revolution.

Next year will be the eighth time The Henry Ford has hosted the America’s Industrial Revolution workshop. This deep learning experience has touched almost 500 teachers in the past 11 years – we estimate over 700,000 students have been impacted!

This year we are making some exciting tweaks that will make the week even more fruitful and more fun.

The biggest change is that we are adding a bus tour of Industrial Revolution-era Detroit. Participating teachers come from all over the country (and sometimes abroad, if they are teaching in military schools, etc.) and they just can’t miss our neighboring city which had such a pivotal role in America’s industrial story. On Monday evening, the second night of the workshop, teachers will take a tour bus to explore a few key areas of Detroit. We will visit Hamtramck, Highland Park, the Ford Piquette Avenue Plant and Corktown, allowing us to move through Detroit history from the era of a frontier surrounded by farmland, to a growing city fueled by industrial production that came to spawn the king of American manufacturing, the automobile industry.

Henry Ford designed the Model T in a secret room at the Piquette Plant.

We have found that participating teachers are often history junkies (just like ourselves) hungry for more learning. So, during our daily site visits to Greenfield Village we will use our knowledgeable master presenters as guides. We invite you to try to stump them with the great questions we know teachers always have.

Speaking of historical learning, we have updated the workshop reading list to include some more recent and more diverse pieces of scholarship on the Industrial Revolution. I particularly enjoyed Steel Drivin’ Man: John Henry, the Untold Story of an American Legend by Scott Reynolds Nelson. It tells about a historian’s journey to uncover the real story behind the folk song about John Henry, investigating if there was truly an African-American convict working on the railroad who died in a contest with a steam drill.

We want to encourage more useful lesson-planning time, too. So we have allocated time during the day to spend with colleagues of similar grades/subjects to plan lessons and to visit the Benson Ford Research Center to make use of our primary sources. We will also encourage teachers to use those primary sources virtually through our online collections. Teachers will see our rich collections in use by the scholars each morning, too.

Read and touch primary sources at the Benson Ford Research Center.

And it’s not just for social studies teachers. The workshop will be useful in many types of K-12 classrooms. Obviously if you teach the period of the Industrial Revolution, or eras following it, this background is indispensable for you. Science, technology and engineering teachers will discover concrete, society-changing examples of the concepts they teach. English Language Arts teachers will experience a taste of the eras that produced literature like Little House on the Prairie, The Jungle, Mark Twain, slave narratives, and (from across the pond) Dickens’ many works. Art teachers may find themselves inspired by the beauty of the machinery, as did Diego Rivera and Charles Sheeler at the Ford Rouge Factory.

Rivera was inspired by the Ford Rouge Factory for his “Detroit Industry” fresco cycle at the Detroit Institute of Arts. THF116582

Sounds fun, doesn’t it? To learn more about the workshop, and to apply, please visit thehenryford.org/neh. Applications are due March 1.

Christian W. Overland is Executive Vice President of The Henry Ford and Project Director, America’s Industrial Revolution at The Henry Ford.

Catherine Tuczek is Curator of School and Public Learning at The Henry Ford.

by Catherine Tuczek, by Christian W. Øverland, events, Michigan, Detroit, educational resources, education, teachers and teaching

Looking Back to Move Forward

If you’ve walked through “With Liberty and Justice for All” in Henry Ford Museum, you’re familiar with the long and complicated history of social transformation, including civil rights and race relations, in America. Some artifacts, like the Rosa Parks Bus, are primary sources in this story, but we also hold collections that offer a more oblique take, such as about 100 photo negatives we’ve just digitized relating to five days of civil unrest in Detroit in July 1967.

The images come from Detroit Edison, which was charged with the very normal work of restoring electricity under very abnormal conditions. While the photos primarily document the power company’s work in the wake of the unrest, the events of the preceding days and their aftermath are omnipresent, as you can see in this image. We undertook this digitization project as part of our participation in “Detroit 67: Looking Back to Move Forward,” “a multi-year community engagement project of the Detroit Historical Society that brings together diverse voices and communities around the effects of an historic crisis to find their place in the present and inspire the future.”

During 2017, we shared more collections-based stories related to the complex roots of, and reactions to, Detroit 67, in keeping with our mission to inspire people to help shape a better future. For now, visit our Digital Collections to browse all of the July 1967 Detroit Edison images.

Additional Readings:

- The Ingersoll-Rand Diesel-Electric Locomotive: Boxy but Significant

- Pioneers of Electricity

- #InnovationNation: Power & Energy

- Power by the Quarter

1960s, 20th century, power, Michigan, electricity, digital collections, Detroit, by Ellice Engdahl, African American history

Mentoring Youth at The Henry Ford

In 1990, a partnership was formed between The Henry Ford and Wayne-Westland Community Schools that would revolutionize the way The Henry Ford looked at community outreach. High School students would spend the first half of their days in the classroom, then be transported to The Henry Ford in taxis where they would spend the remainder of their school day working alongside full-time employees learning vital work skills, forming positive relationships, and creating memories that would last a lifetime.

Twenty-six years later the foundation of the program remains the same. Students from the district continue to make the daily commute to The Henry Ford (although in school buses rather than taxis) where they work in placements ranging from the William Ford Barn, Firestone Farm, Institutional Advancement, banquet kitchens and restaurants, and the Ford Rouge Factory Tour. They now have the opportunity to obtain additional academic credits by completing online courses, and participate in community engagement by practicing service learning with second-grade classrooms at an elementary school in the district on a weekly basis. Service learning allows our students to give back to their communities, and realize the impact they can have on the lives of others.

The students we serve have been identified by their counselors and principals for being at-risk for graduation. Academic struggles usually stem from a multitude of underlying issues such as an unstable home life, mental/physical health issues, or perhaps just lacking a sense of belonging in this world. People learn in different ways and normal schooling isn’t for everyone; the Youth Mentorship Program provides an atmosphere where students can succeed in an environment different from the traditional classroom.

The Youth Mentorship Program is a source of pride here at The Henry Ford. It’s one of the clearest ways we inspire people to learn from these traditions to help shape a better future, as our mission statement proudly states. Unlike most programs at The Henry Ford, the Youth Mentorship Program caters to a smaller group; approximately 12-15 students per semester. The students have the ability to participate in the YMP for a semester or longer, depending on what their schedule allows. Although small in numbers, we believe the YMP is a program that runs ‘an inch wide and a mile deep.’ Although we have a great desire to reach all youth in need in our community, small group size allows for more one-on-one opportunity as well as an overall intimate atmosphere. A quote we hear amongst our students year after year is how the YMP is truly like a family.

It’s incredibly inspiring to watch these students learn their place in the world and become good and successful citizens of their community. Whether it’s passing classes and earning credits, serving The Henry Ford’s guests in a banquet kitchen or restaurant, shearing sheep at Firestone Farm, or walking across a stage to grab their high school diplomas, the Youth Mentorship Program opens the eyes of students to opportunities they may never imagined with overwhelming cheers of support. It truly has deep and lasting impact on the students it serves each semester, as well as the students’ families, The Henry Ford staff, and the Wayne-Westland community.

Help us continue making our community impact by making a donation to the Youth Mentorship Program this Giving Tuesday. How can your donation help?

- $10 can provide a semester's worth of school supplies for a student

- $30 will help uniform one student

- $50 supplies a month's worth of meals for a student

- $200 pays for one online course for a student to complete to earn credit

- $2,500 provides transportation for one student for the year

Continue Reading

Michigan, philanthropy, #GivingTuesday, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, educational resources, education, school, childhood, by Emily Koch

Behind the Scenes with IMLS: Cleaning Objects

One of the main components of The Henry Ford’s IMLS-funded grant is the treatment of electrical objects coming out of storage. This largely involves cleaning the objects to remove dust, dirt, and corrosion products. Even though this may sound mundane, we come across drastic visual changes as well as some really interesting types of corrosion and deterioration, both of which we find really exciting.

One of the main components of The Henry Ford’s IMLS-funded grant is the treatment of electrical objects coming out of storage. This largely involves cleaning the objects to remove dust, dirt, and corrosion products. Even though this may sound mundane, we come across drastic visual changes as well as some really interesting types of corrosion and deterioration, both of which we find really exciting. An electrical drafting board during treatment (2016.0.1.28)

An electrical drafting board during treatment (2016.0.1.28)

Conservation specialist Mallory Bower had a great object recently which demonstrates how much dust we are seeing settled on some of the objects. We’re lucky that most of the dust is not terribly greasy, and thus comes off of things like paper with relative ease. That said, it’s still eye-opening how much can accumulate, and it definitely shows how much better off these objects will be in enclosed storage.

Before and after treatment images of a recording & alarm gauge (2016.0.1.46)

The recording and alarm gauge pictured above underwent a great visual transformation after cleaning, which you can see in its before-and-after-treatment photos. As a bonus, we also have an image of the material that likely caused the fogging of the glass in the first place! There are several hard rubber components within this object, which give off sulfurous corrosion products over time. We can see evidence of these in the reaction between the copper alloys nearby the rubber as well as in the fogging of the glass. The picture below shows where a copper screw was corroding within a rubber block – but that cylinder sticking up (see arrow) is all corrosion product, the metal was actually flush with the rubber surface. I saved this little cylinder of corrosion, in case we have the chance to do some testing in the future to determine its precise chemical composition.

Hard rubber in contact with copper alloys, causing corrosion which also fogged the glass (also 2016.0.1.46). Hard rubber corrosion on part of an object – note the screw heads and the base of the post.

Hard rubber corrosion on part of an object – note the screw heads and the base of the post.

This is another example of an object with hard rubber corrosion. In the photo, you can see it ‘growing’ up from the metal of the screws and the post – look carefully for the screw heads on the inside edges of the circular indentation. We’re encountering quite a lot of this in our day to day work, and though it’s satisfying to remove, but definitely an interesting problem to think about as well.

There are absolutely more types of dirt and corrosion that we remove, these are just two of the most drastic in terms of appearance and the visual changes that happen to the object when it comes through conservation.

We will be back with further updates on the status of our project, so stay tuned.

Louise Stewart Beck is Senior Conservator at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, IMLS grant, conservation, collections care, by Louise Stewart Beck, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Tracing Innovation, Resourcefulness, and Ingenuity in... Beverages

From November 20, 2016, through March 5, 2017, our colleagues at the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) are presenting an exhibition called Bitter|Sweet: Coffee, Tea & Chocolate. The exhibit will trace the impact of these beverages in Europe, beginning in the late 16th century. One set from The Henry Ford’s collections—this late 18th century tea service—will be on loan to the DIA, helping visitors understand what a formal tea setting would have looked like.

As we learned more about the exhibition, we saw additional parallels between the DIA’s goals and our own collections’ artifacts and themes, and ways our collections can extend the messages of the exhibit. The DIA will help explain how these new tastes spawned a design revolution and entirely new industries devoted to creating specialized tableware; our Made in America exhibit in Henry Ford Museum covers how British innovations in power and production machinery made way for the increasingly precise manufacture of porcelain and other mass-produced goods to support these needs, beginning the Industrial Revolution. Bitter|Sweet will focus on Europe, but The Henry Ford’s collections explore how the craze for these new beverages spread to America—including the tale of early American artisan and entrepreneur Paul Revere.

The exhibit will be interactive, allowing guests to explore via all five of their senses, which is similar in approach to Greenfield Village—for instance, being able to experience the sights, sounds, and smells of historic chocolate-making in our Holiday Nights in Greenfield Village program. And last, coffee, tea, and chocolate all remain popular today, allowing us to bring the past forward and show how these historic drinks fit into life in modern America.

Over the course of the exhibit, we’ll be adding links to this post that explore some of these themes in our collections. We hope these will provide a deeper understanding of the impact these three once-exotic drinks have had, from the earliest days of our country’s history right on through to the takeout coffee in your hand.

Drinking Chocolate, American-Style

Chocolate beverages in the collection

Coffee in the collection

Tea in the collection

Paul Revere and The Henry Ford's Tie to Tea

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Detroit, food, Detroit Institute of Arts, by Ellice Engdahl, beverages

Strange sounds will soon float through the air at The Henry Ford. Ghostly, warbling, hypnotic sounds. Reverberations that might be described as pure science fiction—as seeming “out-of-this-world.” These provocative sounds will rise out of an instrument called the theremin, developed in 1920 by Russian and Soviet inventor Léon Theremin. Famously, it is one of the only instruments that is played without physically touching it, and is considered to be the world’s first practical, mass-produced, and portable electronic instrument. These instruments offer a deep range of sonic possibility; learning to play one is a stirring experience.

At Maker Faire Detroit, July 30-31, 2016, Dorit Chrysler will provide several theremin workshops with KidCoolThereminSchool, a workshop program “dedicated to inspire and nurture creative learning and expression through innovative music education, art and science.” On Saturday, youth workshops (ages 4-13) will be held on a first come-first served basis at 11am and 1pm, followed by an adult workshop (ages 14 and above) at 4pm. On Sunday, youth workshops will be held at 1pm, followed by an adult workshop at 4pm. Maker Faire attendees are encouraged to arrive early to guarantee a place in the workshop, as each session is limited to ten participants. Additional guests are welcome to observe the workshop and test a theremin afterwards. Workshops typically run 45mins to 1hour, and will be held in the upper mezzanine area in the Heroes of the Sky exhibit.

Dorit Chrysler is rarity in the realm of musical performance: she is one of the few theremin players in the world who is considered to be a virtuoso of the instrument. She has accompanied an impressive list of bands including The Strokes, and Blonde Redhead, Swans, Cluster, ADULT., Dinosaur Jr., and Mercury Rev. Additionally, as part of her visit to Maker Faire, Dorit will give a performance each day at 3:15pm in The Henry Ford’s Drive-In Theatre, followed by a short Q&A session.

Kristen Gallerneaux, our Curator of Communications and Information Technology, had the opportunity to speak with Dorit Chysler about theremins, her music career, and the importance of collaboration.

Can you explain, using a few key words or phrases—as fanciful as you want them to be—how the theremin sounds?

The granddaughter of the Lev Termen, the theremin's inventor once told me, you have to play the theremin with your soul - to me the sound at its best translates your slightest physical motions into a haunting & delicate soundscape, like weaving winds, tickled butterflies or howls to the moon, and yes, a theremin can sound exquisitely lyrical, but—at its worst, it can also sound like stepping on a cats tail.

How did your introduction to and love of the theremin as an instrument begin? What was your creative background before committing to the theremin?

Having studied musicology in Vienna, I had been an active composer and also played guitar and sang in a rock band - when encountering the theremin at a friend’s house, I was instantly touched by its unusual interface, dynamic potential, the quixotic efforts necessary in controlling its pitch -why had the theremin not been more popular? It clearly deserved more attention.

How can the presence of a theremin influence the structure of a song?

A theremin is surprisingly versatile - it can be applied in solo voicing (just like violin or guitar) or looping monophonic voices atop of each other, which creates a very unique weaving effect or dynamically in swoops and other gestural movements generated through its unique interface of motion translating into sound.

Are there any “quirks” to playing this instrument live?

Playing a theremin live can be a challenge, as circuitry, wind (outdoors) or Hearing Aid ‘Loop’ T-coil Technology in concert halls, just to name a few, can interfere with the instrument. In addition, if you don't hear yourself well onstage, it is impossible to play in tune—so if playing with other instruments, such as an orchestra or a band with drummers, it is a challenge that can only be mastered with your own mixer and an in ear mic. Needless to say, all of this does not contribute in making the theremin a more popular instrument, the technical challenge playing live is real but can be mastered.

While commercial theremins are available via Moog Music, Inc., the theremin you sometimes play in your live shows doesn’t look like a commercial model. Is there a story behind who built it? Any special skills that creator may have had to work hard to learn in order to make the instrument a reality?

I own several different theremin models and sometimes play a Hobbs Theremin, created by Charlie Hobbs. This prototypes has hand-wound coils and a very responsive volume antenna which permits very dynamic playing.

What is the strangest setting in which you have played the theremin?

Many diverse settings seem to offer themselves to a thereminist. Some of my favorite ones have been: playing in front of Nikola Tesla's ashes, resting inside a gold ball sitting on a red velvet pillow at the Tesla Museum in Belgrade, or inside an ancient stone castle ruin, atop a mountain in Sweden, or on a wobbly boat off Venice during sunset and with creaming ducks, at the Carnival in Brazil on a busy street filled with dancing people, and finally, a market place in a small town in Serbia, when an orthodox priest held his cross against the theremin to protect his people from "the work of the devil."

Could you talk a little about the importance of collaboration, and perhaps talk about a project that you are especially fond of where collaboration had a key role?

I strongly believe in collaboration—its challenges and the new and unforeseen places it may take you. My biggest challenge this year has been playing with the San Francisco Symphony orchestra, to be surrounded by a sea of acoustic instruments sounded incredible and was a great sonic inspiration. We all had to trust each other and some of the traditional classical musicians of the ensemble eyed the electric theremin with great suspicion! Also I enjoyed playing with Cluster, stone cold improvising together onstage, or with a loud rock ensemble, filling the main stage at Roskilde festival with Trentemoeller, looking at a sea of thousands of people. This Fall I am committed to projects in collaboration with a project in Detroit with the band ADULT., a French band called Infecticide (they remind me of a political French version of Devo), a children’s theremin orchestra, and a theremin musical production for Broadway. Stylistically a theremin can fit in nowhere or anywhere, which opens many doors of collaboration

Can you tell us a little bit about how KidCoolTheremin school began? What other sorts of venues have you travelled this program to?

KidCoolThereminSchool began very organically, when children and adults were so eager to try the theremin themselves after concerts. I developed a curriculum and started classes at Pioneerworks, a center for art and science in Red Hook, NY. We were supported by Moog Music in Asheville, NC, where I had been teaching students over the course of six months. KidCoolThereminSchool has been going global ever since, we have had sold out classes in Sweden, Switzerland, Detroit's MOCAD, Houston, NYC, Moogfest, Vienna, and Copenhagen. This fall, KidCoolThereminSchool will go to Paris and Berlin as well as free classes in Manhattan as part of the "Dame Electric" festival in NY, Sept. 13-18th.

Why is it important for young people and new adult audiences to have the chance to try a theremin?

Ever since its inception, the theremin as a musical instrument has been underestimated—it merely hasn’t found its true sound as of yet. In this age of technology, a theremin's unique interface of motion to sound, seems contemporary and accessible. Amidst a sea of information, the very physical and innovative approach to different playing techniques can allow each player to find their own voice of expression, learning to listen and experiment, to train motorics and musical skills in a playful and creative way.

What can people expect to learn at the KidCool workshops at Maker Faire?

Due to time restrictions, we will offer introductory classes on the theremin. We will go through the basics of sound generation—and ensemble playing is sometimes all it takes for someone to get inspired in wanting to dive further into the sonic world of the theremin.

Is there anything you are particularly excited to see at the museum?

Yes, the collection apparently holds two RCA theremins. They are currently not on display but we (the NY Theremin Society, which I cofounded) would very much like to help examine and determine what it would take to operate these instruments one day, and to even play them in concert at the museum in the future. For a long time now I wanted to see the permanent collection of The Henry Ford!

Europe, New York, immigrants, Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, women's history, technology, school, musical instruments, music, Maker Faire Detroit, events, education, childhood

Take Me Home Huey

The Vietnam War is remembered as “the Helicopter War” for good reason. The Huey helicopter played a pivotal role serving the U.S. Armed Forces in combat as well as bringing thousands of soldiers and civilians alike back to safety. The helicopter’s prominent rotor “chop” and striking visual as it flew in groups across the sky, became iconic symbols of a challenging period in our nation’s history; symbols that continue to evoke powerful feelings today.

The Henry Ford is proud to host a special display on the front lawn of Henry Ford Museum: Take Me Home Huey is mixed-media sculpture created from the remains of an historic U.S. Army Huey helicopter that was shot down in 1969 during a medical rescue in Vietnam.

Artist Steve Maloney conceived of the piece to draw attention to the sacrifices made by veterans of the U.S. Armed Forces, and the 50th anniversary of the start of the Vietnam War. Maloney partnered with Light Horse Legacy (LHL), a Peoria, Arizona-based nonprofit and USA Vietnam War Commemorative Partner focused on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. LHL acquired the Huey helicopter – #174 – from an Arizona boneyard, re-skinned and restored it, and delivered it to the Maloney to transform into art for healing.

Learn more about Take Me Home Huey here.

Greg Harris is Senior Manager of Events & Program Production at The Henry Ford.

Asia, Michigan, flying, events, Dearborn, by Greg Harris, art, 21st century, 20th century, 2010s, 1960s

Henry Ford and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra

Concert in the Ford Symphony Gardens, Century of Progress International Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, 1934. THF212561

For the past 24 years the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and The Henry Ford have teamed up for Salute to America, our annual concert and fireworks celebration in Greenfield Village. But the affiliation between the DSO and our organization goes back much farther than that.

Preparing for a Performance in Ford Symphony Gardens, Century of Progress International Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, 1934. THF212547

The connection dates back to the 1934 Chicago World's Fair, A Century of Progress International Exposition. Ford Motor Company’s exhibits were housed in the famous Rotunda building and also included the Magic Skyway and the Ford Symphony Gardens. The large amphitheater of the Symphony Gardens hosted several musical and stage acts, including the DSO, who Ford sponsored for 150 concerts over the course of the year. The symphonic notes proved so popular that Henry and Edsel Ford decided to launch a radio program featuring selections from symphonies and operas - the Ford Sunday Evening Hour. The weekly program played to over 10,000,000 listeners each broadcast over the CBS network (the same network that now presents The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation). Musical pieces were played by DSO musicians under the name Ford Symphony Orchestra, a 75-piece ensemble, and were conducted by Victor Kolar, the DSO’s associate director, for the first few years of the show. Pieces ranged from symphony classics including works by Handel, Strauss, Liszt, Wagner, Handel, Puccini, Bizet, and Tchaikovsky (including, of course, the 1812 Overture), to some of Henry Ford’s favorite traditional and folk songs like Turkey in the Straw and Annie Laurie, and even included popular tunes such as Night and Day by Cole Porter.

Each broadcast featured guest stars, soloists, and singers such as Jascha Heifetz, Grisha Goluboff, Gladys Swarthout, Grete Stükgold, and José Iturbi. The broadcast performances were open to the public for free, first at Orchestra Hall from 1934-1936, and then at the Masonic Temple 1936-1942. The show ran from 1934-1942, September-May with 1,300,000 live attendees and countless radio listeners tuning in.

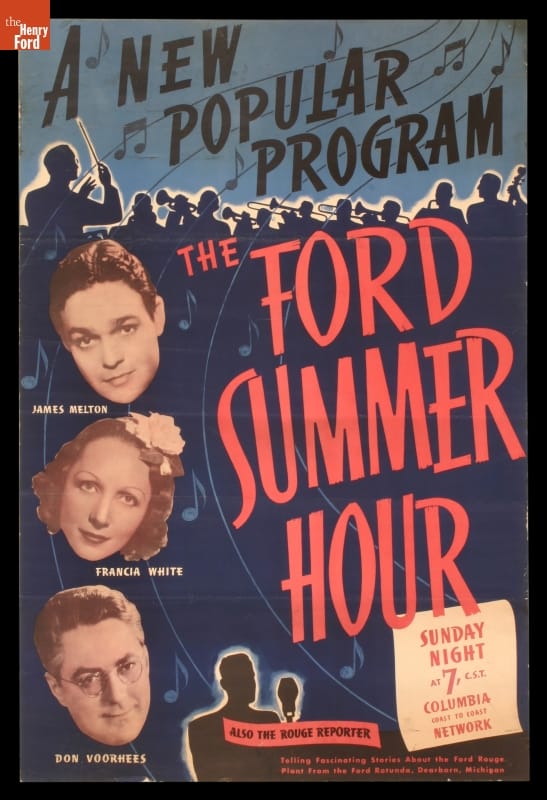

Advertising Poster, The Ford Summer Hour, 1939. THF111542

Salute to America is our summer music tradition, and listeners in 1939 must have wanted some summer-themed music as well because Henry and Edsel started the Ford Summer Hour that year. Like the winter program, it was broadcast each Sunday evening on CBS, from May to September and featured a smaller 32-piece orchestra, again mostly made up of DSO musicians. Guest stars and conductors appeared, such as Don Voorhees, James Melton, and Jessica Dragonette.

The show included music from Ford employee bands like the River Rouge Ramblers, Champion Pipe Band, and the Dixie Eight. This was a program of lighter music, popular songs, and tunes from musical comedies and operettas. Apparently not everyone appreciated the lighter fare; a letter from a concerned listener stated:

“...as the strains of the trivial program of Ford Summer Show float into my room, I am moved to contrast them with the fine programs of your winter series, and to wonder why the myth persists that in hot weather the human mentality is unequal to the strain of listening to good music. Pardon me while I switch my radio to station WQXR which has fine music the year round.”

Strong words from the listening public, though apparently not the majority as the summer program rivaled the winter program with about 9,000,000 listeners per broadcast. The Ford Summer Hour, broadcast from the Ford Rotunda, only ran three seasons, but played a wide range of music for listeners such as Heigh Ho from Snow White, Dodging a Divorcee, selections from Carmen, Oh Dear, What Can the Matter Be, and One Fine Day from Madame Butterfly.

Both programs ceased by 1942 with the opening of World War II. Henry Ford II tried to bring back the Ford Sunday Evening Hour in 1945, broadcasting the same type of music by DSO musicians, but times and tastes had changed and the program was discounted after the first season.

Kathy Makas is a Benson Ford Research Center Reference Archivist at The Henry Ford. To learn more about the Ford Sunday Evening Hour or Ford Summer Hour, visit the Benson Ford Research Center or email your questions to us here.

Greenfield Village, events, Salute to America, by Kathy Makas, Ford Motor Company, Edsel Ford, Ford family, radio, world's fairs, Michigan, Henry Ford, music, Detroit

Homegrown Wearables

DESIGNERS DISILLUSIONED WITH FAST FASHION LOOK TO CREATE A GRASSROOTS GARMENT INDUSTRY ONE CITY AND ONE HANDMADE SHIRT AT A TIME

Laura Lee Laroux is full of confidence, even though some peers say she shouldn’t be.

Laroux, 36, moved to Bozeman, Montana, with seven sewing machines and 12 rolls of fabric in a U-Haul earlier this year, intent on making the rugged town at the northern foot of the Gallatin Range the new headquarters of her clothing line. She calls it RevivALL because she upcycles old materials into new garments, such as ruffled dresses fashioned from men’s shirts and hip bags revived from leather scraps bought from a recreational vehicle manufacturer.

Laroux had been overly busy and underearning in her previous home of Eugene, Oregon, running a clothing boutique, co-producing a local fashion week and, in the snatches of remaining time, working on developing RevivALL. But then, like so many bold Americans, from the pioneers to Kerouac on down, she concluded that her destiny, her chance to leave the old muddle behind and pursue her dream full time, lay elsewhere. “I just got some kind of rumbling inside me that said I have to leave Eugene,” said Laroux.

But Bozeman, population 37,000, isn’t New York or Los Angeles, teeming with seamstresses, fashion buyers and media. Why does she think she can make it there?

The same could be asked of legions of other upstart fashion designers setting up shop in locales such as Lawrence, Kansas; Nashville; and Detroit, none fashion capitals likely to be featured on Project Runway.

Something is afoot.

The odds of upstarts breaking profitably into the $2.5 trillion international fashion business remain long, but American entrepreneurs like Laroux have been newly emboldened to try by a confluence of cultural and economic forces. These include an appetite among some activist consumers to opt out of the fast-fashion system; Web stores like Etsy that connect small makers to buyers everywhere; low costs in postindustrial American cities; the decline of New York’s garment district; and fledgling pockets of support for apparel startups by government and not-for-profit groups. The result of all this has been the growth — sometimes halting, occasionally stunted, but often encouraging — of grassroots garment industries across the American landscape.

“Not all designers have to come to New York,” said Lisa Arbetter, editor of the influential fashion magazine StyleWatch, which has a per-issue circulation of 825,000. “Every line doesn’t have to be sold in Saks.”

A LITTLE IS ENOUGH

It might seem counterintuitive, but the fact that 97 percent of the clothing sold in the United States is now made overseas, up from 50 percent in 1990 and 10 percent in the 1960s, has created opportunity for American makers. While Zara, H&M, Gap and Fast Retailing, the parent of Uniqlo, have annual sales of more than $74 billion combined, some of the fashion-forward want to wear clothes that a million other people aren’t also slithering into.

What’s especially sweet about the kind of apparel businesses those like Laroux are starting is that a little success can be enough. Their ambition is not to become the next Betsey Johnson or Yves St. Laurent, but merely to gain the satisfaction of earning enough money selling dresses made from shower curtains, cruelty-free handbags or bespoke belt buckles to quit their boring day jobs.

“I’m close to making a living on my own stuff,” said Leslie Kuluva, who has seen sales of her line of LFK T-shirts printed in Lawrence, Kansas, rise every year since 2006. Kuluva says when she started, “I used to print them on my living room table and lay them out on the couch to dry, and cats would be walking all over them.”

Now, the “stuff” she creates in her professional print shop on East 8th Street in the college town includes men’s ties she buys at thrift stores and upcycles by printing clever designs on them, along with baby onesies and adult shirts she buys wholesale and unprinted from American Apparel, adds LFK logos to and sells at a profit of roughly $10 a garment. The line is carried at downtown shops such as Wonder Fair and Ten Thousand Villages eager to support local makers.

MORE THAN A HOBBY

Of course, having one artist or even a dozen eke out a living printing shirts one by one is not on its own enough to jump-start the economy of a town or change fashion as we know it. The challenges in taking a step up from that by launching a relatively small national apparel brand are formidable, as would-be entrepreneur Lisa Flannery learned over the past few years. A veteran of two decades of toil in various roles at big brands in the Manhattan fashion business, Flannery attempted to start her own surfwear line.

“You need serious capital for development and production; unlimited amounts of time for sourcing, designing and fitting,” Flannery shared in a long and deeply detailed gush during a short break from her current job as a technical design manager at a national clothing brand. “And a partner or really good friends and family to help you with the sales, marketing and PR, legalities and accounting, etc., because you need to handle design and production, which are really jobs for multiple people — if you can manage to handle that, then you confront massive minimums, which is why you need all of that capital — minimums on fabric, trims and the amount of units the factory will produce for you — most China factories want at least 3,000 units — otherwise you are making small lots locally at very high prices, which your potential customers scoff at because they are used to Forever 21/Zara/H&M prices. And then if you do manage to get some traction, you can bet someone is going to knock you off at a much lower price.”

Flannery ended up spending more than $10,000 and gave up when, after subsisting on four hours of sleep a night, her health started to fail. She’s not optimistic about the long-term prospects for Laroux and others.

Such barriers to big dreams are why Karen Buscemi runs the Detroit Garment Group (DGG), a three-year-old nonprofit with an ambitious agenda. “We are trying to make Michigan the state for the cut-and-sew industry,” said Buscemi, a former fashion magazine editor.

Funded by donors including two automobile seating manufacturers, the DGG offers as one of its five major programs a fashion incubator. It takes up to 10 fashion entrepreneurs; installs them in offices in Detroit’s Tech Town building; gives monthly workshops on making business plans; provides access to high-end design equipment for free; assigns seven mentors across legal, sustainability, sales and other fields; and, at the end of a year, sets up a showroom where retailers come and hopefully buy clothes and start a wholesale relationship with the incubees. Those not admitted to the full program can sign on as an associate member for $100 a month to use the high-end printers, pattern-digitizers and other machines to create a fashion collection.

DGG’s apprenticeship programs in pattern-making and sewing machine repair promise to help convert the unemployed into garment workers. (DGG’s certificate classes in industrial sewing are offered at a few schools, including Henry Ford College in Dearborn, which is not affiliated with The Henry Ford.) Meanwhile, DGG is working with a variety of state agencies to establish a full-blown garment district, taking advantage of the decline in New York, where the district, due to high costs and foreign outsourcing, is a shell of its old self. Los Angeles has already shown it can be done, becoming a new apparel-making center.

The idea could very well work in Detroit, too, said StyleWatch editor Arbetter. “They are training people in a manufacturing skill that dovetails into the history of that town as a manufacturing center, and by doing that, they are creating businesses and creating jobs. It seems that particular city is ripe for this.”

One key, Buscemi said, is starting small by helping young designers find stable footing. “They want to come out the door from college and be entrepreneurs,” she noted. “But unless you have had experience, how are you going to do that and turn it into a real business rather than a hobby you are doing on the side?”

A COMMUNITY WITHIN

Apparel brands can change a city. In Nashville in 2009, the jeans shop Imogene + Willie opened in a former gas station on 12th Avenue South. Its informal vibe, with cool folks lounging on couches next to stacks of blue jeans and thick belts — a few doors up from the famed guitar shop Corner Music — helped establish a neighborhood aesthetic.

As co-owner with her husband, Carrie Eddmenson explains in the brand’s online statement: “The way Matt and I operate has always involved a mix of uncertainty reinforced by intuition, call it a gut feeling.”

The words could be a manifesto for Nashville, where guts, gut feelings and flights of inspiration have for a century oozed through the city’s honky-tonk veins, only recently spilling out into creative fields beyond music.

Although the jeans are made in Los Angeles, the store’s bustling neighborhood, now known by the hipster moniker “12 South,” is one of the emblems of Nashville’s ferocious resurgence. Chef Sean Brock credits the city’s apparel scene for his decision to open a Nashville outpost of his award-winning restaurant Husk. “I came back to visit friends,” Brock said, moments after slicing a local ham for thrilled patrons in the dining room last winter. “And there was just a buzz. People were coming from New York and LA to do things like make leather belts.”

In Bozeman, Laroux has identified what there is of a garment industry and has taken steps to become a part of it. There are companies producing backpacks there, and Red Ants Pants, a brand that is like Carhartt for women, is headquartered in Bozeman. Even though not all of these companies produce apparel in Montana, their presence, Laroux figures, means there must be expert seamstresses, fabric cutters and other production people around, some of them likely willing to take second jobs for an ambitious, youngish designer.

In her first 10 days in town, Laroux met with a woman who runs a coworking space and a screen-printing business, another who has a clothing boutique and another, Kate Lindsay, who founded Bozeman Flea, a market for artists and makers. Laroux’s goal is to start earning $50,000 annually, after expenses. Some of that income may come from selling patterns for her dresses for $10 each via websites such as Indiesew; some from showing at an upcoming fashion event in Helena, Montana, and at Bozeman Flea; some from opening a local shop with other designers; some from sales of sock garters on the e-commerce maker superstore Etsy; and some, perhaps, from catching the fancy of a buyer from a national retailer looking for a unique American-made product.

The extra bedroom in the faux colonial she rents with friends, her share being $600 monthly, has become, for now, a design studio and sewing room. Not for long, Laroux said. “In three months, in my ideal world, I would have this little storefront I’ve been looking at downtown, with my studio in the basement and three other designers that have studio space, and we take turns running the shop.”

Long ago at fashion school in New York, Laroux had a burned-out professor who told the class none of them were ever going to really make it as designers. “’You’re just going to be getting coffee for people at design houses,’” she recalled him saying, acting as if administering this dose of reality was a favor.

Maybe it was. He made her angry, and now she’s making her stand, assembling a fashion posse.

By Allen Salkin for The Henry Ford Magazine. This story ran in the June-December 2016 edition.

21st century, 2010s, women's history, The Henry Ford Magazine, Michigan, making, fashion, entrepreneurship, Detroit, design, by Allen Salkin