Posts Tagged model ts

Celebrating the National Historic Vehicle Register

America’s car culture is a subject for music, movies, and postcards—and for serious study and preservation. / THF104062

There’s an exciting new changing exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. In partnership with our friends at the Hagerty Drivers Foundation, we’re spotlighting some of the nation’s most significant automobiles and trucks. Some of these vehicles introduced new ideas in engineering or design, others found glory on the race track, and a few lit up the silver screen. In all cases, these vehicles left a mark on American history important enough to earn them a place on the National Historic Vehicle Register.

We inaugurate this collaborative display with a car from the world of popular culture. For those of us who were teens in the 1980s, the movies of writer-director John Hughes were inescapable. Films like Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club, Weird Science, and Pretty in Pink captured the Reagan-era teenage zeitgeist—and timeless teenage angst—to a T. But for self-styled Gen-X slackers, one film in the Hughes catalog stands above the rest: Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

There’s probably no need to summarize the well-known plot (see here if you disagree). Suffice it to say, high school senior Ferris (Matthew Broderick) convinces best friend Cameron (Alan Ruck) and girlfriend Sloane (Mia Sara) to join him on his own personal skip day through Chicago. The plot really gets rolling, so to speak, when Ferris convinces Cameron to let them take his father’s 1961 Ferrari 250 GT California on their adventures. It doesn’t end well. The Ferrari becomes the target of Cameron’s longstanding anger with his father, and its accidental destruction forces some serious interpersonal growth.

This (genuine) 1958 Ferrari 250 GT California was part of Henry Ford Museum’s 1965 Sports Cars in Review exhibit. / THF139028

We’re delighted to be able to exhibit that Ferrari. Well, not that Ferrari… the one that got destroyed. For that matter, what we’re showing isn’t even a Ferrari. It’s a 1985 Modena Spyder California—an authentic-looking replica built by Modena Design & Development in El Cajon, California. It’s one of three Modena replicas used in shooting the movie. (Even in the mid-1980s, a genuine Ferrari 250 GT was too valuable to risk in film work.) This beloved pop-culture car is a playful way to kick off our celebration of a serious project: the National Historic Vehicle Register.

The National Historic Vehicle Register has its roots in the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER). Established jointly in 1969 by the National Park Service, the American Society of Civil Engineers, and the Library of Congress, HAER documents significant sites and structures associated with America’s engineering and industrial history. According to established HAER guidelines, nominated structures are documented with written reports, photographs, and technical drawings. These materials are then deposited in the Library of Congress. Generally, a listing in the HAER does not, in itself, protect a structure from possible demolition. It does, however, “preserve” that structure for the future via HAER’s extensive documentary materials.

HAER has documented buildings, bridges, and even airplanes, but it’s never documented cars. Recognizing the need for some similar mechanism to record significant automobiles and trucks, the Historic Vehicle Association (HVA) was formed in 2009. Modeling itself on HAER, the HVA had four founding principles:

- To document and recognize significant vehicles in a national register

- To establish and share best practices for the care and preservation of significant vehicles

- To promote the historical and cultural importance of motor vehicles

- To protect automotive history through affiliations with museums and academic institutions, through educational programs, and through support of relevant legislation

The Historic Vehicle Association, in collaboration with the U.S. Department of the Interior, established the National Historic Vehicle Register (NHVR) in 2013 and, in January 2014, it added the first car to its list. HVA selected a 1964 Shelby Cobra Daytona Coupe, one of six built by Carroll Shelby and his Shelby American team to compete in sports car races. Apart from Mr. Shelby himself, the Cobra Daytona Coupe was also developed with legendary racing figures like Pete Brock, Ken Miles, and Phil Remington.

CSX2287, the first Shelby Cobra Daytona Coupe, won the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1964. Fifty years later, it became the first entry on the National Historic Vehicle Register. / THF130368

We should pause to note that, of necessity, the National Historic Vehicle Register contains individual cars. The register does not list the Cobra Daytona Coupe as a model. Rather, it specifically includes chassis number CSX2287—the first of the six built, and the only one built completely at Shelby American’s Venice, California, shop. CSX2287 won the GT class at the 1964 Sebring 12-Hour race, competing as number 10, with drivers Dave MacDonald and Bob Holbert. The car later set 27 national and international land speed records at the Bonneville Salt Flats, with Craig Breedlove at the wheel. CSX2287 is now in the collections of the Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Following its selection, the Cobra Daytona Coupe—like all subsequent vehicles on the register—was thoroughly documented for the NHRV. Specialists researched the car through written documents and spoken interviews, they photographed it from multiple angles, and they measured the car using sophisticated laser scanners. (You can learn more about the scanning process in this clip from The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation.) The resulting materials were then sent to the Library of Congress for long-term preservation.

The Historic Vehicle Association was founded with philanthropic support from Hagerty, the world’s largest specialist insurance provider for historic vehicles. In more recent years, the work of the HVA has been folded into the Hagerty Drivers Foundation, which manages the National Historic Vehicle Register with the U.S. Department of the Interior.

The Marmon Wasp driven by Ray Harroun, winner of the 1911 Indianapolis 500. / THF229391

To date, more than 30 vehicles have been added to the National Historic Vehicle Register. There are celebrated race cars like the 1907 Thomas Flyer that won the 1908 New York to Paris Automobile Race, the 1911 Marmon Wasp that won the first Indy 500, and one of NASCAR’s “Fabulous Hudson Hornets” driven by Herb Thomas.

Volkswagen’s groundbreaking Type 2 Transporter is represented on the NHVR by a van that served a higher purpose: supporting Black Americans in the Civil Rights Movement. / THF105564

There are vehicles that participated in large national events, like a 1918 Cadillac employed by the U.S. Army in World War I, or a 1966 Volkswagen Transporter used in humanitarian efforts supporting Black Americans on Johns Island, South Carolina, during the Civil Rights Movement, or a 1969 Chevrolet Corvette driven by Apollo astronaut Alan Bean, who landed on the Moon in November 1969.

The 1964 Chevrolet Impala lowrider is a car culture icon, illustrated by this remote-controlled model. / THF151539

The wide world of American car culture is wonderfully represented by a 1932 Ford V-8 hot rod built by Bob McGee, a 1951 Mercury Coupe modified for Masato Hirohata by “King of Kustomizers” George Barris, and the pioneering 1964 Chevrolet Impala lowrider “Gypsy Rose,” customized by Jesse Valadez.

Preston Tucker’s 1948 Tucker 48 made a mark in life and on screen. / THF135047

The register doesn’t overlook the automobile’s contributions to popular culture. Apart from the replica Ferrari used in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, the list includes a 1968 Ford Mustang driven by Steve McQueen during the influential car chase in Bullitt, and a 1981 DeLorean DMC-12 that carried Michael J. Fox’s Marty McFly to 1955 before returning him back to the future. Preston Tucker’s 1947 Tucker 48 prototype is something of a movie car too. Yes, it inspired a real-life production vehicle, but it also inspired the 1988 film Tucker: The Man and His Dream, starring Jeff Bridges.

The 15 Millionth Ford Model T traveled from Greenfield Village to the National Mall in April 2018, after it was added to the NHVR. / Photo courtesy Hagerty Drivers Foundation

Some of you may be wondering if anything from The Henry Ford’s collections is listed on the National Historic Vehicle Register. I’m happy to report that, yes, we are represented by (what else) a Ford Model T added to the list in 2018. It’s not just any T, of course, but the 15 Millionth Ford Model T, which was the ceremonial “last” Model T built before Ford ended production in favor of the 1928–1931 Model A. Like most of the vehicles added to the register, our 15 Millionth Model T traveled to Washington, D.C., where it was displayed on the National Mall—to honor the car, but also to draw attention to the NHVR and the importance of preserving America’s automotive heritage. The NHVR research team also produced a 23-minute documentary on the Ford Model T and its enormous influence.

The register continues to grow. Likewise, The Henry Ford will continue to display a rotating selection of register cars in the years ahead. It’s a fun way to celebrate America’s car culture, but it’s also an opportunity to recognize the important and ongoing work of the National Historic Vehicle Register.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Model Ts, race cars, racing, popular culture, movies, by Matt Anderson, Henry Ford Museum, cars

Frank Kulick: Early Ford Racer

Frank Kulick sitting in a 1910 Ford Model T race car. / THF123278

Frank Kulick (1882–1968) was a lucky man who beat rivals and cheated death on the race track. But his greatest stroke of luck may have been being in the right place at the right time. Born in Michigan, Kulick started his first job—in a Detroit foundry—at age 12. He was listed as a spring maker in the 1900 census. But in 1903 he was working for Northern Manufacturing Company—an automobile company founded by Detroit auto pioneer Charles Brady King.

That’s where Frank Kulick met Henry Ford.

Ford stopped by Northern to borrow a car. Impressed with young Kulick, Ford lured him to his own Ford Motor Company, where Kulick signed on as one of Ford Motor’s first employees. Kulick was there at Lake St. Clair in January 1904 when Henry Ford set a land speed record of 91.37 miles per hour with his “Arrow” racer. Not long after, Ford told Kulick, “I’m going to build you a racing car.” By that fall, Frank Kulick was driving to promote Ford Motor Company on race tracks and in newspapers.

Frank Kulick scored his early victories driving this four-cylinder Ford racer. Its engine consisted of a pair of two-cylinder (1903) Model A engines mated together. / THF95388

Kulick went head-to-head with drivers who became legends in American motorsport—people like Barney Oldfield, whose cigar-chomping bravado set the mold for racing heroics, and Carl Fisher, who established Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1909 and the Indianapolis 500 two years later. Kulick firmly established his credentials with an improbable win at Yonkers, New York, in November 1904. Through skillful driving in the corners and a bit of good luck (which is to say, bad luck for his competitors), Kulick’s little 20-horsepower Ford pulled out a win against a 90-horsepower Fiat and a 60-horsepower Renault. Kulick covered a mile in 55 seconds—an impressive racing speed of 65 miles per hour.

Frank Kulick (second from right) and Henry Ford (third from left) were photographed in New Jersey with the Model K racer in 1905. / THF95015

Frank Kulick’s four-cylinder, 20-horsepower car was superseded in 1905 by a larger car with a six-cylinder, 60-horsepower engine. It was one of a series of cars using engines based on the six-cylinder unit that appeared in the Ford Model K. The bigger engine did not bring better results. Henry Ford himself drove one of the cars twice in the summer of 1905, chasing new land speed records on the New Jersey beach. But the car came up short each time.

With Kulick at the wheel, Ford tried again for a record at Ormond Beach, Florida, in January 1906—this time with the six-cylinder engine improved to 100 horsepower. But Kulick had trouble with the soft sand, and he managed no better than 40 miles per hour on the straightaway. (The record was broken at the Ormond Beach event—but by a steam-powered Stanley that hit 127.66 miles per hour.)

The end of the road for Ford’s six-cylinder racers nearly ended Frank Kulick’s career—and his life. It happened in October 1907, on the one-mile oval at the Michigan State Fairgrounds near Detroit. Kulick was trying to lap the dirt track in fewer than 50 seconds—a speed better than 72 miles per hour. His latest car was dubbed “666”—a name that simultaneously called attention to its cylinder count and paid homage to Henry Ford’s earlier “999.” In retrospect, that nefarious name was a bad omen.

Miraculously, Frank Kulick survived this crash in 1907, but it left him with a broken leg and a permanent limp. / THF125717

As Kulick was going through a turn on the fairgrounds oval, his rear wheel collapsed. Car and driver went careening off the track, through the fence, and down a 15-foot embankment. When rescuers arrived, they found Kulick some 40 feet from his wrecked racer. He was alive, but with his right kneecap fractured and his right leg broken in two places. Frank Kulick survived the crash, but his injuries healed slowly and imperfectly. He wore a brace for two years, and he walked with a limp for the rest of his life—his right leg having come out of the ordeal 1 ½ inches shorter than his left leg. The “666” was repaired, but it never competed again.

Henry Ford was horrified by Kulick’s accident, and he very nearly swore his company off racing for good. It wasn’t until 1910 that Kulick competed again under the company’s colors. By then, Ford Motor Company wasn’t building anything but the Model T, so Kulick naturally raced in a series of highly modified T-based cars. Arguably, his first effort in the renewed campaign was more show business than sport. Kulick went to frozen Lake St. Clair, northeast of Detroit, that February to challenge an ice boat. He easily won the match and earned quick headlines for the Model T.

Kulick posed in a Model T racer at the Algonquin Hill Climb, near Chicago, in 1912. / THF140161

Over the next two years, Kulick and his nimble Model T racers crossed the country competing—and frequently winning—road races and hill climbs. Despite Kulick’s success, Henry Ford remained lukewarm on racing. Ford Motor Company built nearly 70,000 cars in 1912 and still struggled to meet customer demand, so it certainly didn’t need the promotion—or problems—that came with an active motorsport program. Kulick later recalled that, after a race at Detroit in September 1912, Henry pulled $1,000 in cash from his pocket and told Frank, “I’ll give you that to quit racing.” Despite the generous offer (almost $30,000 in today’s dollars), Kulick continued a bit longer.

Frank Kulick may have started having second thoughts the next month. While practicing for the Vanderbilt Cup road race in Milwaukee, he grew concerned about the narrow roadway. There wasn’t enough room to pass another car without dipping into a ditch, so Kulick protested and dropped out of the contest. His concerns proved well founded when driver David Bruce-Brown was killed in the next round of practice.

It was the 1913 Indianapolis 500 that finally changed Kulick’s career path. Then in its third running, the Indy 500 was well on its way to becoming the most important race in the American motorsport calendar. Henry Ford was determined to enter Kulick in a modified Model T. But Indy’s rules specified a minimum weight for all entries. The Ford racer weighed in at less than 1,000 pounds—too light to meet the minimum. Indy officials rejected the modified T, and a frustrated Henry Ford reportedly replied, “We’re building race cars, not trucks.” With that, there would be no Ford car in the Indianapolis 500—in fact, there would be no major factory-backed Ford racing efforts for 22 years.

Kulick’s later career involved more genteel assignments, like driving the ten millionth Ford on a coast-to-coast publicity tour in 1924. Here, he takes a back seat to movie stars Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks. / THF134645

Frank Kulick’s racing days were over, but he remained with Ford Motor Company for another 15 years. His assignments varied from research and development to publicity. In 1924, Kulick was charged with driving the ten millionth Ford Model T on a transcontinental tour from New York to San Francisco. Three years later, Kulick was called on to help celebrate the 15 millionth Model T. This time, rather than driving it across the country, Kulick—as one of Ford Motor Company’s eight senior-most employees—had the honor of helping stamp digits into the engine’s serial number plate. It was perfectly fitting that, as someone who’d done so much to promote the Model T through racing, Kulick was there to make his mark on the ceremonial last T. Kulick left Ford not long after that. He had done well investing in real estate, which afforded him a comfortable retirement.

Frank Kulick passed away in 1968. He survived to see Ford Motor Company achieve its great racing triumphs at Indianapolis and Le Mans during the “Total Performance” era. He also lived long enough to sit for an interview with author Leo Levine, whose 1968 book, Ford: The Dust and the Glory, remains the definitive history of Ford racing in the first two-thirds of the 20th century. Levine wrote a whole chapter on Frank Kulick—but then, Frank Kulick wrote a whole chapter in Ford’s racing history.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Remembering Al Unser, Sr. (1939-2021)

- Eight Questions with Vaughn Gittin, Jr.

- Race Cars of Driven to Win

- 2016 Ford GT Full-Size Clay Model, 2014

Michigan, Model Ts, Indy 500, cars, by Matt Anderson, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, Henry Ford, race cars, race car drivers, racing

Remembering Mose Nowland (1934-2021)

Mose Nowland, with wife Marcia and daughter Suzanne, at The Henry Ford in June 2021.

The Henry Ford lost a dear friend and a treasured colleague on August 13, 2021, with the passing of Mose Nowland. When he joined our Conservation Department as a volunteer in 2012, Mose had just concluded a magnificent 57-year career with Ford Motor Company—most of it in the company’s racing program—and he was eager for something to keep himself occupied in retirement. We soon discovered that “retire” was just about the only thing that Mose didn’t know how to do.

To fans of Ford Performance, Mose was a legendary figure. He joined the Blue Oval in 1955 and, after a brief pause for military service, he spent most of the next six decades building racing engines. Mose led work on the double overhead cam V-8 that powered Jim Clark to his Indianapolis 500 win with the 1965 Lotus-Ford. Mose was on the team behind the big 427 V-8 that gave Ford its historic wins over Ferrari at Le Mans—first with the GT40 Mark II in 1966 and then again with the Mark IV in 1967. And Mose was there in the 1980s when Ford returned to NASCAR and earned checkered flags and championships with top drivers like Davey Allison and Bill Elliott.

Mose with one of his creations during Ford’s Total Performance heyday.

Following his retirement, Mose transitioned gracefully into the role of elder statesman, becoming one of the last remaining participants from Ford’s glory years in the “Total Performance” 1960s. Museums and private collectors sought him out with questions on engines and cars from that era, and he was always happy to share advice and insight. Mose’s expertise was exceeded only by his modesty. He never claimed any personal credit for Ford’s racing triumphs—he was just proud to have been part of a team that made motorsport history. Mose was able to see that history reach a wider audience with the success of the recent movie Ford v Ferrari.

Michigan, Dearborn, The Henry Ford staff, 21st century, 20th century, racing, race cars, philanthropy, Old Car Festival, Model Ts, Mark IV, making, in memoriam, Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, engines, engineering, collections care, cars, by Matt Anderson, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Ford Methods and the Ford Shops

THF97674

In 1913, Ford Motor Company combined the standardization of interchangeable parts with the subdivision of labor and the fluid movement of work to workers to create the world’s most influential assembly line. We are unusually fortunate that two keen observers of industry, Horace Lucien Arnold and Fay Leone Faurote, were there to document it.

Arnold, a correspondent for The Engineering Magazine, grasped the significance in Ford’s work and began a series of articles on the company’s Highland Park factory. After Arnold’s untimely death, Faurote completed and compiled the articles in the 1915 study Ford Methods and the Ford Shops. The book’s detailed descriptions, numerous photographs and careful diagrams give us a vivid window into Highland Park at a seminal moment in manufacturing history.

Looking back now, the most remarkable aspect of Ford Methods and the Ford Shops is the liberal level of access Ford gave to its authors. It is difficult to imagine Google or Apple opening their doors to today’s press and giving unfettered access to employees, workspaces, and sensitive production figures. The company’s cooperation speaks volumes about Henry Ford’s confidence in Highland Park. He knew that his methods were far ahead of his competitors, and there was little fear of them catching up too quickly.

Workers place magnets on Model T flywheels, 1913. Fittingly, successful experiments with a moving magneto assembly line “sparked” Ford’s adoption of assembly line techniques throughout Highland Park. / THF96001

The assembly line came to Ford Motor Company in stages. Around April 1, 1913, flywheel magnetos were placed on moving lines. Instead of one worker completing one flywheel in some 20 minutes, a group of workers stood along a waist-high platform. Each worker assembled some small piece of the flywheel and then slid it along to the next person. One whole flywheel came off the line every 13 minutes. With further tweaking, the assembly line produced a finished flywheel magneto in just five minutes.

Flow charts and maps in the book illustrated the logical, sequential arrangement of machine tools at Highland Park. / THF600582

It was a genuine “eureka” moment. Ford soon adapted the assembly line to engines, and then transmissions, and, in August 1913, to complete chassis. The crude “slide” method was replaced with chain-driven delivery systems that not only reduced handling but also regulated work speed. By early 1914, the various separate production lines had fused into three continuous lines able to churn out a finished Model T every 93 minutes—an extraordinary improvement over 12½ hours per car under the old stationary assembly methods.

Workers lower an engine into a Model T chassis, 1913. Note that the line is not yet chain-driven. Ford constantly improved the assembly line in search of time and cost savings. / THF91696

The incredible time and cost savings realized through the assembly line allowed Henry Ford to lower the Model T’s price, which increased demand for the car, which then prompted Ford to seek even greater manufacturing efficiencies. This feedback loop ultimately produced some 15 million Model Ts selling for as little as $260 each.

The peak annual Model T production of 1.8 million in 1923 was still years away when Arnold and Faurote made their study. They did not capture Ford’s assembly line in a fully realized form. In fact, the line never was finished. It existed in a state of flux, under constant review for any potential improvements. Adjusting the height of a work platform might save a few seconds here, while moving a drill press might shave some more seconds there. Several such small changes could yield large productivity gains.

Ford Methods and the Ford Shops captures a manufacturer that has just discovered the formula for previously unimagined production levels. The assembly line is groundbreaking, and Ford knows it. The company’s openness with its methods, and Arnold’s and Faurote’s efforts to document and publicize them, helped make the Model T assembly line the industrial milestone that we still celebrate more than a century later.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. This post was adapted from a 2013 post in our Pic of the Month series.

Additional Readings:

- The Wool Carding Machine

- Positioning and Synchronicity on Paper

- Fordson Tractor No. 100,000

- Thomas Blanchard’s Wood Copying Lathe

research, Model Ts, cars, Ford Motor Company, manufacturing, by Matt Anderson, Henry Ford, books

Henry Ford: Case Study of an Innovator

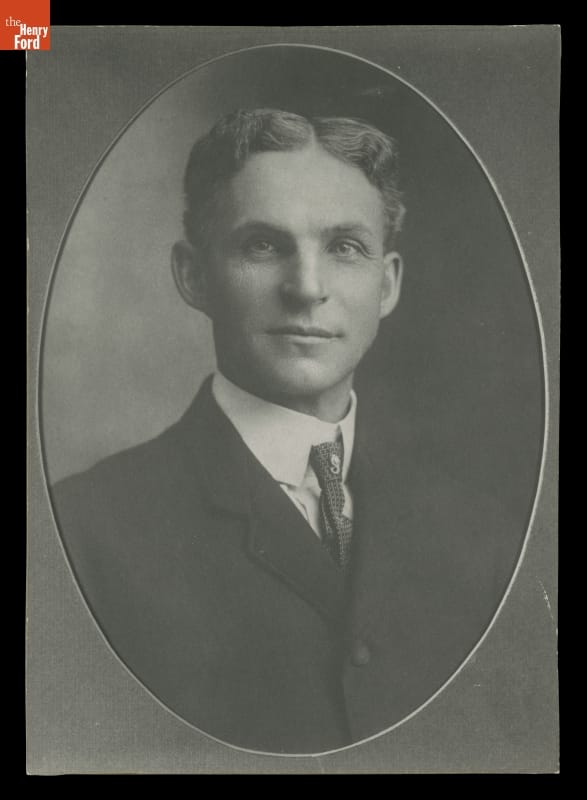

Henry Ford’s first official Ford Motor Company portrait, 1904. / THF97952

Henry Ford did not invent the automobile. But more than any other single individual, he was responsible for transforming the automobile from an invention of unknown utility into an innovation that profoundly shaped the 20th century and continues to affect the 21st. His work at Ford Motor Company revolutionized the automotive industry, setting new standards for production and accessibility.

Innovators change things. They take new ideas—sometimes their own, sometimes other people’s—and develop and promote those ideas until they become an accepted part of daily life. Innovation requires self-confidence, a taste for taking risks, leadership ability, and a vision of what the future should be. Henry Ford had all these characteristics, but it took him many years to develop all of them fully.

Portrait of the Innovator as a Young Man

Ford’s beginnings were perfectly ordinary. He was born on his father’s farm in what is now Dearborn, Michigan, on July 30, 1863. At this time, most Americans were born on farms, and most looked forward to being farmers themselves. Early on, Ford demonstrated some of the characteristics that would make him successful. In his family, he became infamous for taking apart his siblings’ toys as well as his own. He organized other boys to build rudimentary waterwheels and steam engines. He learned about full-size steam engines by becoming acquainted with the engines’ operators and pestering them with questions. He taught himself to fix watches and used the watches themselves as textbooks to learn the basics of machine design. Thus, at an early age, Ford demonstrated curiosity, self-confidence, mechanical ability, the capacity for leadership, and a preference for learning by trial and error. These characteristics would become the foundation of his whole career.

Artist Irving Bacon depicted Henry Ford in his first workshop, along with friends, in this 1938 painting. / THF152920

Ford could simply have followed in his father’s footsteps and become a farmer. But young Henry was fascinated by machines and was willing to take risks to pursue that fascination. In 1879, he left the farm to become an apprentice at a machine shop in Detroit. Over the next few years, he held jobs at several places, sometimes moving when he thought he could learn more somewhere else. He returned home in 1882 but did little farming. Instead, he operated and serviced portable steam engines used by farmers, occasionally worked in factories in Detroit, and cut and sold timber from 40 acres of his father’s land.

By now, Ford was demonstrating another characteristic—a preference for working on his own rather than for somebody else. In 1888, Ford married Clara Bryant, and in 1891 they moved to Detroit. Ford had taken a job as night engineer for the Edison Electric Illuminating Company—another risk on his part, because he did not know a great deal about electricity at this point. He took the job in part as an opportunity to learn.

Henry Ford (third from left, in white coat) with other employees at Edison Illuminating Company Plant, November 1895. / THF244633

Early Automotive Experiments: Failure and Then Success

Henry was a skilled student, and by 1896 had risen to chief engineer of the Illuminating Company. But he had other interests. He became one of the scores of other people working in barns and small shops trying to make horseless carriages. Ford read about these other efforts in magazines, copying some of the ideas and adding some of his own, and convinced a small group of friends and colleagues to help him. This resulted in his first primitive automobile, the Quadricycle, completed in 1896. A second, more sophisticated car followed in 1898. These early experiments laid the groundwork for his future endeavors in the automotive industry.

Henry Ford’s 1896 Quadricycle Runabout, the first car he built. / THF90760

Ford now demonstrated one of his most important characteristics—the ability to articulate a vision and convince other people to sign on and help him achieve that vision. He convinced a group of businessmen to back him in the biggest risk of his life—starting a company to make horseless carriages. But Ford knew nothing about running a business, and learning by doing often involves failure. The new company failed, as did a second. His first venture, the Detroit Automobile Company, failed due to the poor quality of its vehicles. Ford tried again, this time with the Henry Ford Company. But disputes over the new company’s direction soon caused Ford and his investors to part ways.

To revive his fortunes, Ford took bigger risks, building and even driving a pair of racing cars. The success of these cars attracted additional financial backers, and on June 16, 1903, just before his 40th birthday, Henry incorporated his third automobile venture, the Ford Motor Company.

The early history of Ford Motor Company illustrates another of Henry Ford’s most valuable traits—his ability to identify and attract outstanding talent. He hired a core of young, highly competent people who would stay with him for years and make Ford Motor Company into one of the world’s great industrial enterprises. He hired a core of young, highly competent people who would stay with him for years, reshaping America’s automotive industry while building Ford Motor Company into one of the world’s great industrial enterprises.

Print of Norman Rockwell's painting, "Henry Ford in First Model A on Detroit Street." / THF288551

The new company’s first car was called the Model A, and a variety of improved models followed. In 1906, Ford’s 4-cylinder, $600 Model N became the best-selling car in the country. But by this time, Ford had a vision of an even better, cheaper “motorcar for the great multitude.” Working with a small group of employees, he came up with the Model T, introduced on October 1, 1908. The Model T was a game-changer, designed to be simple, reliable, and ultimately affordable for the average American.

The Automobile: A Solution in Search of a Problem

As hard as it is for us to believe, in 1908 there was still much debate about exactly what automobiles were good for. We may see them as a necessary part of daily life, but the situation in 1908 was very different. Americans had arranged their world to accommodate the limits of the transportation devices available to them. People in cities got where they wanted to go by using electric street cars, horse-drawn cabs, bicycles, and shoe leather because all the places they wanted to go were located within reach of those transportation modes.

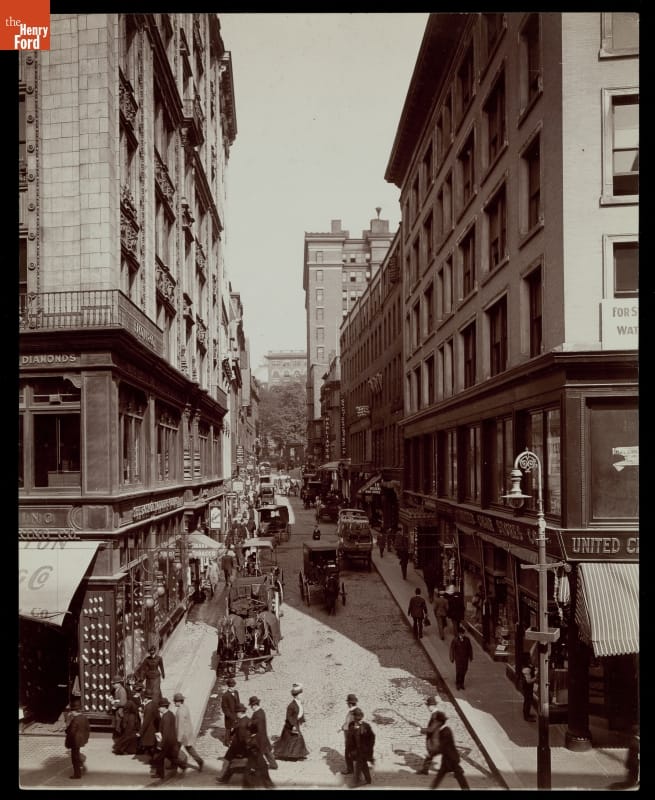

This Boston street scene, circa 1908, shows pedestrians and horse-drawn carriages on the road—but no cars. / THF203438

Most of the commercial traffic in cities still moved in horse-drawn vehicles. Rural Americans simply accepted the limited travel radius of horse- or mule-drawn vehicles. For long distances, Americans used our extensive, well-developed railroad network. People did not need automobiles to conduct their daily activities. Rather, the people who bought cars used them as a new means of recreation. They drove them on joyrides into the countryside. The recreational aspect of these early cars was so important that people of the time divided motor vehicles into two large categories: commercial vehicles, like trucks and taxicabs, and pleasure vehicles, like private automobiles. The term “passenger cars” was still years away. The automobile was an amazing invention, but it was essentially an expensive toy, a plaything for the rich. It was not yet a true innovation.

Henry Ford had a wider vision for the automobile. He summed it up in a statement that appeared in 1913 in the company magazine, Ford Times:

“I will build a motor car for the great multitude. It will be large enough for the family but small enough for the individual to run and care for. It will be constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise. But it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one—and enjoy with his family the blessings of hours of pleasure in God’s great open spaces.”

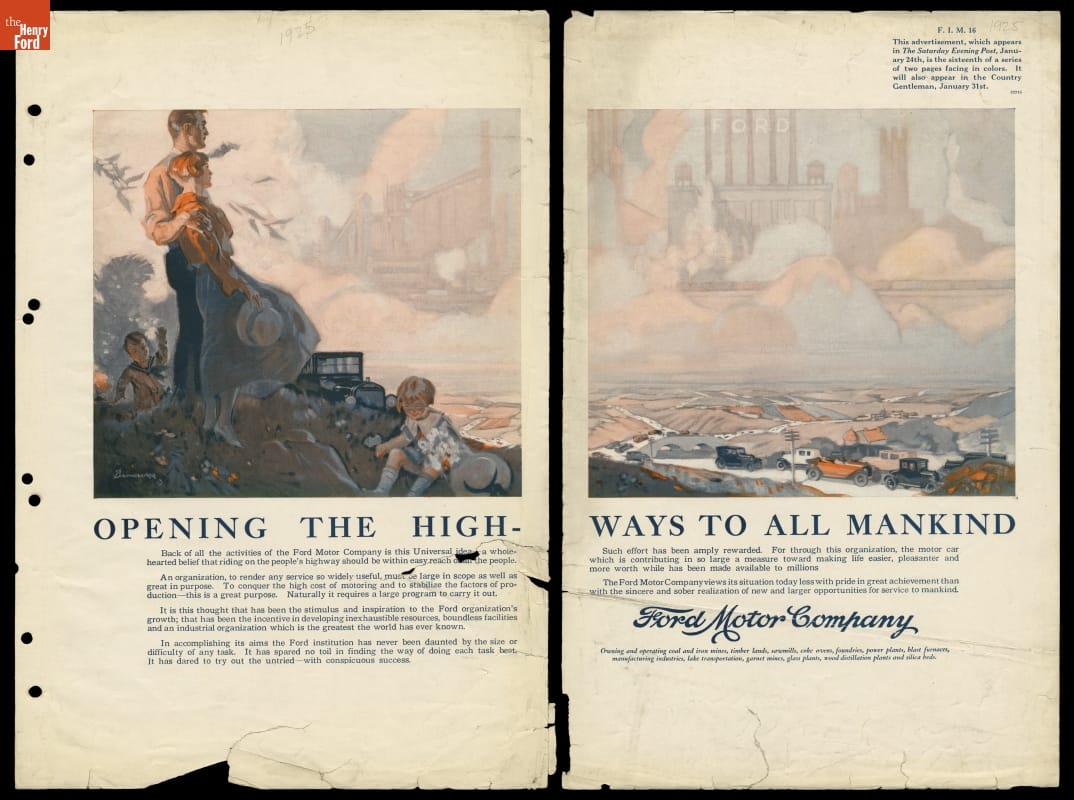

This 1924 Ford ad, part of a series, echoes the vision expressed 11 years earlier by Henry Ford: “Back of all of the activities of the Ford Motor Company is this Universal idea—a wholehearted belief that riding on the people’s highway should be in easy reach of all the people.” / THF95501

It was this vision that moved Henry Ford from inventor and businessman to innovator. To achieve his vision, Ford drew on all the qualities he had been developing since childhood: curiosity, self-confidence, mechanical ability, leadership, a preference for learning by trial and error, a willingness to take risks, and an ability to identify and attract talented people.

One Innovation Leads to Another

Ford himself guided a design team that created a car that pushed technical boundaries. The Model T’s one-piece engine block and removable cylinder head were unusual in 1908 but would eventually become standard on all cars. The Ford’s flexible suspension system was specifically designed to handle the dreadful roads that were then typical in the United States. The designers utilized vanadium alloy steel that was stronger for its weight than standard carbon steel. The Model T was lighter than its competitors, allowing its 20-horsepower engine to give it performance equal to that of more expensive cars. The Model T forever changed the automotive industry and American culture. Its impact can still be felt today.

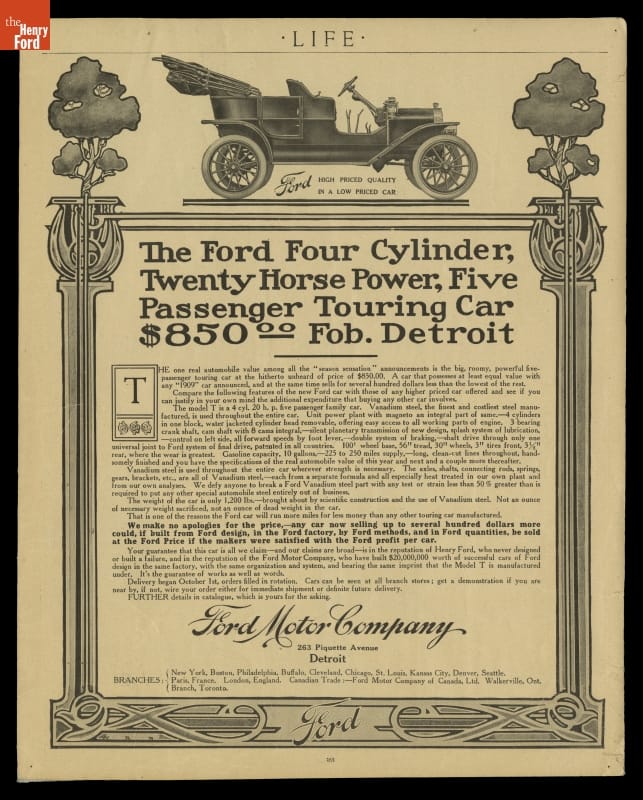

1908 advertisement for the 1909 Ford Model T. In advertisements, Ford Motor Company emphasized key technological features and the low prices of their Model Ts. Ford's usage of vanadium steel enabled the company to make a lighter, sturdier, and more reliable vehicle than other early competitors. / THF122987

The new Ford car proved to be so popular that Henry could easily sell all he could make, but he wanted to be able to make all he could sell. So Ford and his engineers began a relentless drive both to raise the rate at which Model Ts could be produced and to lower the cost of production.

In 1910, the company moved into a huge new factory in Highland Park, a city just north of Detroit. Borrowing ideas from watchmakers, clockmakers, gunmakers, sewing machine makers, and meat processors, Ford Motor Company had, by 1913, developed a moving assembly line for automobiles. But Ford did not limit himself to technical improvements.

When his workforce objected to the relentless, repetitive work that the line entailed, Ford responded with perhaps his boldest idea ever—he doubled wages to $5 per day. With that one move, he stabilized his workforce and gave it the ability to buy the very cars it made. He hired a brilliant accountant named Norval Hawkins as his sales manager. Hawkins created a sales organization and advertising campaign that fueled potential customers’ appetites for Fords. Model T sales rose steadily while the selling price dropped. By 1921, half the cars in America were Model Ts, and a new one could be had for as little as $415.

Norval Hawkins headed the sales department at Ford Motor Company for 12 years, introducing innovative advertising techniques and increasing Ford’s annual sales from 14,877 vehicles in 1907 to 946,155 in 1919. / THF145969

Through these efforts, Ford turned the automobile from an invention bought by the rich into a true innovation available to a wide audience. By the 1920s, largely as a result of the Model T’s success, the term “pleasure car” was fading away, replaced by “passenger car.” Ford’s moving assembly line and $5 day ushered in a new era of mass production and affordability. American society itself was transformed as motorists were free to travel where they wanted, when they wanted.

The assembly line techniques pioneered at Highland Park spread throughout the auto industry and into other manufacturing industries as well. The high-wage, low-skill jobs pioneered at Highland Park also spread throughout the manufacturing sector. Advertising themes pioneered by Ford Motor Company are still being used today. Ford’s curiosity, leadership, mechanical ability, willingness to take risks, ability to attract talented people, and vision produced innovations in transportation, manufacturing, labor relations, and advertising. His legacy is preserved at places like Greenfield Village, showcasing his impact on American life and the evolution of the automotive industry.

What We Have Here Is a Failure to Innovate

Henry Ford was slow to admit that customers no longer wanted the Model T. However, in 1927, he finally acknowledged that shift, and Henry Ford and his son, Edsel Ford, drove this last Model T—number 15,000,000—off the assembly line at Highland Park. / THF135450

Henry Ford’s great success did not necessarily bring with it great wisdom. In fact, his very success may have blinded him as he looked to the future. The Model T was so successful that he saw no need to significantly change or improve it. He did authorize many detail changes that resulted in lower cost or improved reliability, but there was never any fundamental change to the design he had laid down in 1907.

He was slow to adopt innovations that came from other carmakers, like electric starters, hydraulic brakes, windshield wipers, and more luxurious interiors. He seemed not to realize that the consumer appetites he had encouraged and fulfilled would continue to grow. He seemed not to want to acknowledge that once he started his company down the road of innovation, it would have to keep innovating or else fall behind companies that did innovate. He ignored the growing popularity of slightly more expensive but more stylish and comfortable cars, like the Chevrolet, and would not listen to Ford executives who believed it was time for a new model.

But Model T sales were beginning to slip by 1923, and by the late 1920s, even Henry Ford could no longer ignore the declining sales figures. In 1927, he reluctantly shut down the Model T assembly lines and began the design of an all-new car. It appeared in December 1927 and was such a departure from the old Ford that the company went back to the beginning of the alphabet for a name—it was called the Model A.

Edsel and Henry Ford introduce the new Model A at the Ford Industrial Exposition in New York in January 1928. Edsel had worked to convince his father to replace the outmoded Model T with something new. / THF91597

One area where Ford did keep innovating was in actual car production. In 1917, he began construction of a vast new plant on the banks of the Rouge River southwest of Detroit. This plant would give Ford Motor Company complete control over nearly all aspects of the production process. Raw materials from Ford mines would arrive on Ford boats, and would be converted into iron and steel, which were transformed into engines, transmissions, frames, and bodies. Glass and tires would be made onsite as well, and all of this would be assembled into completed cars. Assembly of the new Model A was transferred to the Rouge. Eventually the plant would employ 100,000 people and generate many innovations in auto manufacturing. The River Rouge complex became a symbol of Ford's ambition and scale, a testament to his vision for vertically integrated production.

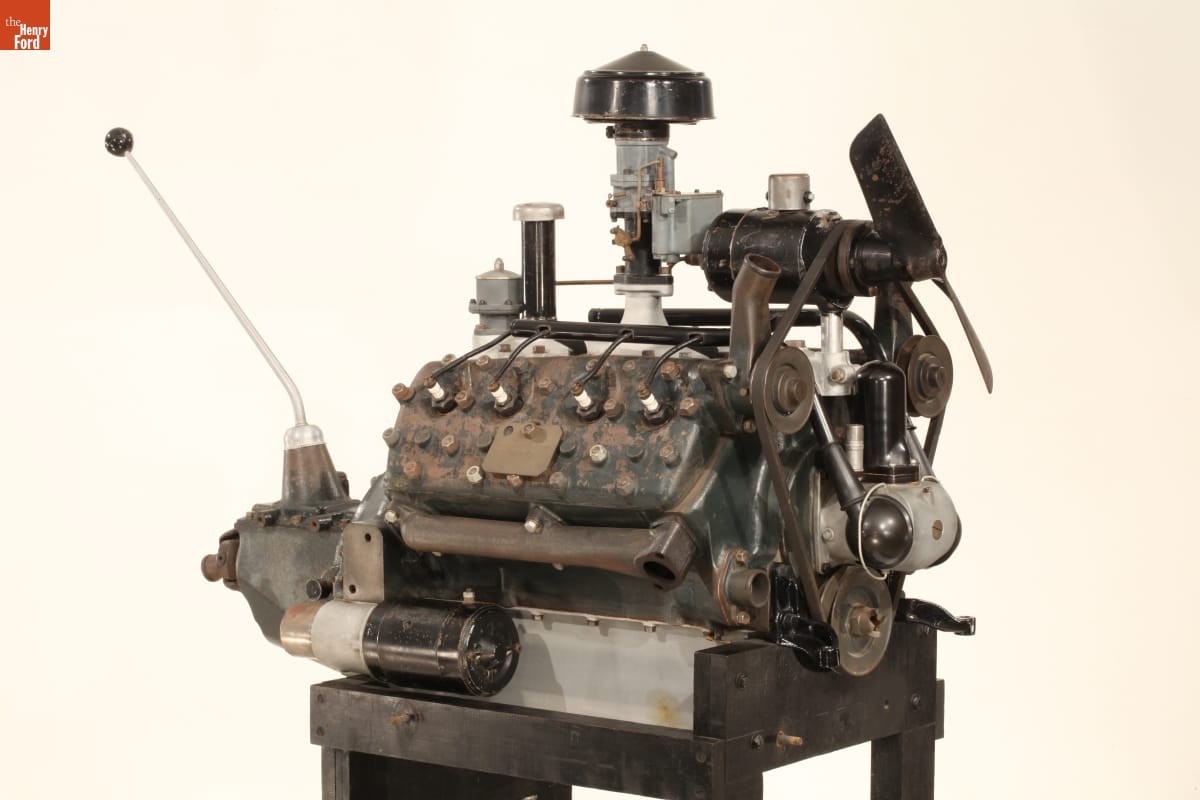

But improvements in manufacturing were not enough to make up for the fact that Henry Ford was no longer a leader in automotive design. The Model A was competitive for only four years before needing to be replaced by a newer model. In 1932, at age 69, Ford introduced his last great automotive innovation, the lightweight, inexpensive V-8 engine. It represented a real technological and marketing breakthrough, but in other areas Fords continued to lag behind their competitors. The Ford factory continued to evolve, but the company faced new challenges in keeping up with changing consumer preferences and technological advancements in the automotive industry.

The V-8 engine was Henry Ford’s last great automotive innovation. This is the first V-8 engine produced, which is on exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / THF101039

By 1936, the company that once sold half of the cars made in America had fallen to third place behind both General Motors and the upstart Chrysler Corporation. By the time Henry Ford died in 1947, his great company was in serious trouble, and a new generation of innovators, led by his grandson Henry Ford II, would work long and hard to restore it to its former glory. Henry’s story is a textbook example of the power of innovation—and the power of its absence. His contributions to the automotive industry and American society are undeniable, but his later resistance to change serves as a cautionary tale.

Bob Casey is former Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. This post is adapted from an educational document from The Henry Ford titled “Henry Ford and Innovation: From the Curators.”

Detroit, Michigan, Dearborn, 20th century, 19th century, quadricycle, Model Ts, manufacturing, Henry Ford, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Ford Motor Company, entrepreneurship, engines, engineering, cars, by Bob Casey, advertising

Passengers rush to board the Overland Limited, which ran between Los Angeles and Chicago over the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe Railway, ca. 1905. / THF207763

Between 1865 and 1920, America’s railroad network increased sevenfold, from 35,085 miles to an all-time high of 254,037 miles in 1916. The rapid expansion of the national rail network corresponded with major technological improvements—including double tracking, improved roadbeds, heavier and faster locomotives, and the elimination of sharp curves—which allowed trains to operate at higher speeds. Travel times were steadily cut year by year. To emphasize time savings, railroad companies began to give their faster lines special names like “flyer,” “express,” and “limited.”

This 1913 timetable for the St. Louis-Colorado Limited line of the Wabash-Union Pacific Railroad boasted that it was the shortest line with the fastest time between destinations. / THF291441

However, increased speed came with disadvantages. High speeds resulted in an increasing number of gruesome railroad accidents caused by both discrepancies in local times and mix-ups between different railroad companies’ timetables.

A catastrophic collision occurred between two passenger trains on the Providence & Worcester Railroad when they failed to meet at a passing siding as scheduled, 1853. / THF622050

Facing governmental intervention to address the problem, the railroads took it upon themselves to enact a single standardized time across the country by dividing the nation into five roughly even time zones. Some people at first rebelled against this arbitrary imposition, especially when the newly drawn time zone designations did not align with local practices. But most people found it increasingly convenient to set their clocks by this new “standard time.”

Residents of Fitchburg, Massachusetts, would have synchronized the time on their personal clocks and watches to the railroad depot clock seen in this ca. 1916 postcard. / THF124830

Another disadvantage, some people complained, was that the increasing speed of railroad travel was unhealthy. Many believed that the rapid pace of life contributed to new forms of stress and anxiety and that the railroad was a key cause of these problems.

Railroad passengers ascending the staircase after arriving in Chicago, via the Illinois Central Railroad, ca. 1907 / THF105820

By 1920, railroad passenger travel was at the highest level it would ever attain. But, with the exception of the unique conditions during World War II, the railroad would never again be the dominant form of personal transportation in America. Within a few decades, the American public would embrace automobiles with the passion they had once given over to the railroads. How did this transfer of allegiance from railroad to automobile occur so effortlessly and completely during the early 20th century, and how does it relate to Americans’ changing concepts of time?

A group of motorists travelling from Davenport, Iowa, to New York, ca. 1905 / THF104740

At first, many railroad managers did not take automobiles seriously—and for good reason. When they were first introduced in the 1890s, automobiles had no practical purpose. They were considered amusing and entertaining playthings for wealthy hobbyists and adventurers.

1909 advertisement for the Pierce-Arrow Motor Car, an automobile geared to wealthy motorists who could afford to have a chauffeur handle the driving for them. / THF88377

Most railroad managers were complacent, agreeing with one claim that “the fad of automobile riding will gradually wear off and the time will soon be here when a very large part of the people will cease to think of automobile rides.” But, as it turned out, the public passion for automobile riding did not wear off. Increasingly, Americans from all walks of life embraced automobiles and their advantages over railroads. By 1910, more than 468,000 motor vehicles had been registered in the United States.

Automobiles would have not achieved the level of popularity that they did without major advancements in the roads on which they traveled. As far back as the 1890s, bicyclists and early motorists had tried to alert the public to, and lobby the government for, better roads—roads that the railroads had ironically either replaced or rendered unnecessary.

The Bulletin and Good Road, the official organ of the League of American Wheelmen, kept bicyclists up to date on advancements relating to the “Good Roads” movement. / THF207011

One reason that people embraced automobiles was because they revived the promise of individual freedom. Compared with railroad travel, motorists were unhampered, free to follow their own path. Elon Jessup, author of several motor camping books, wrote, “Time and space are at your beck and call, your freedom is complete.”

Motorists enjoying life on the road in the Missouri Ozarks, 1923. / THF105550

According to a 1910 American Motorist article, no longer were people tied to intercity train schedules, “rushed meals,” and “rude awakenings.” The motorist was “his own station master, engineer, and porter.” Riding in his own “highway Pullman,” he had “no one’s time to make except his own.” Automobile advocate Henry B. Joy wrote in a 1917 Outlook article that motoring promised “freedom from the shackles of the railway timetable.” Automobiles were also considered a particular advantage for women, who were increasingly venturing out into public spaces to shop, work, socialize, and take pleasure trips.

Four women in a Haynes automobile, travelling from Chicago to New York, ca. 1905. / THF107595

In addition to restoring people’s personal control over their own time, automobiles succeeded in slowing down the fast pace of modern life. Early automobile advocates claimed that railroads were simply too fast. Elon Jessup, in his 1921 book, The Motor Camping Book, described the view from the train as “a blur.” In his 1928 book, Better Country, nature writer Dallas Lore Sharp remarked that railroads rushed “blindly along iron rails” in their “mad dash across the night,” offering passengers only “fleeting impressions.” Automobiles, on the other hand, promised a nostalgic return to a slower time. Harkening back to the “simpler” days of stagecoach and carriage travel, automobiles were “refreshingly regressive.” Instead of being rushed along by “printed schedules and clock-toting conductors,” motorists could stop and start whenever they wanted, or when natural obstacles intervened. A car trip was leisurely, allowing heightened attention to regional variation and uniqueness.

Motorists take a leisurely drive through the countryside on the cover of this September 1924 American Motorist magazine. / THF202475

All told, the automobile liberated the individual who “hated alarm clocks” and “the faces of the conductor who twice daily punched his ticket on the suburban train.” In his 1928 book, Dallas Sharp even claimed that motoring was, in fact, more patriotic than railroad travel because it encouraged people to enjoy the country “quietly” and “sanely.” As a result, the slower tempo of automobile travel was thought to be restorative to frayed nerves brought on by the increasingly hectic pace of life in an urban, industrial society.

No automobile had more impact on the American public than the Model T, introduced in 1908. Envisioned by Henry Ford as a car for “the great multitude,” the Model T was indeed “everyman’s car”—sturdy, versatile, thrifty, and powerful. While Model Ts sold well from the beginning, the low price, extensive dealer network, and easy availability of replacement parts led to a leap in Model T sales after World War I.

Brochure for the 1924 Ford Model T, promoting its use as a vehicle for family pleasure trips. / THF107809

The need and demand for better roads corresponded with the unprecedented rise in Model T sales. The first and most widely publicized of the new, independently funded cross-country highways was the Lincoln Highway (1912), which ran (at least on paper) between New York City and San Francisco, California. In 1916—ironically, the same year that national railroad mileage reached a peak—the U.S. government passed the Federal Aid Road Act, providing grants-in-aid to several states to fund road improvement. The railroad companies watched helplessly as the government subsidized improved roads that extended to villages and hamlets the railroads could never hope to reach.

Effie Price Gladding recounts her cross-country trip on the Lincoln Highway in this 1915 book. The cover points out the states she passed through along the route of this highway. / THF204498

By the end of the 1920s, due in large part to the unprecedented popularity of the Model T, automobiles had gained a “vice-like grip on the American psyche.” Total car sales had leaped from 3.3 million in 1916 to 23 million by the late 1920s. Motorists were not only opting to take cars rather than trains for their regular travel routines, but they were also beginning to take longer-distance trips than they had ever attempted before. As the 1920s closed, Americans were traveling five times farther in cars than in trains. Enthusiasm for the automobile remained high throughout the Great Depression of the 1930s, when massive new road and highway construction projects were initiated to stimulate employment.

Black Americans embraced automobiles to avoid discrimination and humiliation on public transportation—at least until they had to stop to eat, sleep, and fill up with gas. Beginning in 1936, the Negro Motorist Green Book listed “safe places” for Black motorists to stop in towns and cities across the country. / THF99195

Conversely, the Depression was devastating for the railroad companies, who abandoned a record number of miles of existing track during this decade. By the late 1930s, railroad companies were optimistically attempting to revive business by embracing modern new streamlined designs, which claimed to reflect aerodynamic principles and promised a smooth ride incorporating the latest standards of comfort and convenience. A new emphasis on speed led to numerous record-breaking runs.

For its speed, as well as its beauty, comfort, and convenience, the Wabash Railroad’s “Blue Bird Streamliner” of 1950 was touted as “The Most Modern Train in America.” / THF99239

After World War II, the lifting of wartime rationing, the inclusion of two-week paid vacations in most labor union contracts, pent-up demand for consumer goods, and general postwar affluence ensured the automobile industry “banner sales,” which lasted into the 1950s.

Travel brochures like this one abounded after World War II, appealing to family vacationers. / THF202155

State-endorsed toll roads met the immediate postwar demand for motorists’ “right to speedy and accident-free travel over long distance.”

The Pennsylvania Turnpike, the first state-endorsed toll road, officially entered service on October 1, 1940. It currently stretches three times its original length. / THF202550

But the U.S. government’s long-time obsession with highway improvement truly reached a “dizzying crescendo” in 1956, with the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act. This Act called for 46,000 miles of state-of-the-art, limited-access superhighways, to be funded by public taxes on fuel, tires, trucks, buses, and trailers. Although justified for military and national defense purposes, the interstate highway system made it possible for average citizens to reach their destinations faster in their cars than by taking trains.

Although the new urban expressways were promoted as modern advantages, as seen in this 1955 “Auto-Owners Expressway Map” for the Detroit area, in fact, these same expressways cut through and often devastated poor and historically marginalized communities. / THF205968

Ironically, as automobiles became the standard vehicle for long-distance transportation, and highways beckoned motorists with higher speed limits and improved surfaces, the slow, leisurely pace of motoring—so lauded 50 years earlier—had transformed into an outpacing of even the “blurring” speed of railroads.

The wonder of the fast and efficient new expressways is evident in the child’s expression in this 1959 promotional photograph, as he views a futuristic model highway envisioned by researchers at General Motors. / THF200901

For the most part, travelers rejoiced as four-lane divided highways replaced the older two-lane highways. With the new speed and comfort features of cars and improved highways, the impulse toward getting somewhere as rapidly and efficiently as possible, along the straightest path, became the new end goal.

Sources consulted include:

- Belasco, Warren James. Americans on the Road: From Autocamp to Motel, 1910-1945. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1979.

- Douglas, George H. All Aboard: The Railroad in American Life. New York: Paragon House, 1992.

- Gordon, Sarah H. Passage to Union: How the Railroads Transformed American Life, 1829-1929. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1996.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. This blog post is adapted from her M.A. Thesis, “American Dreams and Railroad Schemes: Cultural Values and Early-Twentieth-Century Promotional Strategies of the Wabash Railroad Company” (University of Michigan-Dearborn, 2013).

Additional Readings:

- Steam Locomotive "Sam Hill," 1858

- Canadian Pacific Snowplow, 1923

- Model Train Layout: Demonstration

- Fair Lane: The Fords’ Private Railroad Car

20th century, 19th century, travel, trains, roads and road trips, railroads, Model Ts, cars, by Donna R. Braden

The Henry Ford’s Ingersoll Milling Machine and Mass Production at Highland Park

THF129649

What are the icons of the Industrial Revolution—steam engines, printing presses, combine harvesters, textile machinery? Any such list would surely include Ford’s Model T. Like the other machines that would make the grade it too was a complex mechanism, but it was also a beloved consumer product rooted in personal practical everyday use, and it was a design icon—in its day a symbol of absolute modernity.

The T’s success came about through two revolutions within the Industrial Revolution—those of power generation and distribution, and precision production manufacturing. Developments in the electrical industry liberated Henry Ford and his production experts from the constraints of mechanical power distribution. Earlier systems dictated where machinery was placed based on long straight runs of shafts and associated pulleys. Electric motors powering first groups and then individual machines enabled Ford’s engineers to position machine tools where the production process dictated. It was the incredible machines developed specifically for that process that were crucial to the speed and quality of Model T production.

Henry Ford and his assistants developed a system of mass production at Ford Motor Company’s Highland Park plant that was based on moving components through a refined sequence of manufacturing, machining and assembly steps. Launched in October 1913, Ford’s new system ultimately reduced the time of producing Model Ts from about 12½ man-hours to only 1½ man-hours.

Model Ts contained more than ten thousand parts. Ford’s moving assembly line required that each one of these parts be manufactured to exacting tolerances (the acceptable amount of variation) and be fully interchangeable with any other part of its kind. By organizing the automobile’s construction into a series of distinct small steps and using precision machinery, the assembly line generated enormous gains in productivity.

This is the only survivor of the vast range of custom-designed high-production machine tools used at Ford’s Highland Park plant. THF129616

Machines like this 1912 Ingersoll milling machine were crucial to the high production levels attained at Highland Park. Milling machines are machine tools that rotate cutters to plane or shape surfaces. Teams of Ford specialists collaborated with machine tool designers to develop and continually improve machinery for Highland Park, resulting in milling machines that were capable of undertaking highly accurate, multiple cutting operations on many components at the same time.

One of six similar machines in a careful arrangement of machine tools in Highland Park’s cylinder finishing shop, this planer-type milling machine – both a vertical and a horizontal miller – simultaneously milled the underside and main bearing holders of Model T engine blocks. Cutters on the horizontal spindle shaped the bearing holders, while large cutters on vertical spindles milled the bottom surface of the blocks flat. The machine could mill 15 engine blocks in one batch—loaded and unloaded by semi-skilled labor. The work was physically demanding, and while it did not demand the skills of a trained machinist, it did require dexterity and attention to detail in addition to stamina.

The Henry Ford’s Ingersoll milling machine is represented by one of the six horizontal cross shapes labeled #2 on the left of this diagram, which shows the arrangement of machine tools in the cylinder block machining shop at Highland Park. THF300582

The Ingersoll milling machine first arrived at Ford’s Highland Park plant in December 1912. It was just one of a vast range of new, specialized machines that enabled Ford to mass produce quality, affordable vehicles – and capture 50% of the American market! Today, it is exhibited in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation as the only survivor of the custom-designed high-production machine tools used at Highland Park. Twenty-one feet long and eight feet high, the machine is an imposing presence and a compelling reminder of Ford’s moving assembly line—as important a development as the Model T itself.

Additional Readings:

- Steam Engine Lubricator, 1882- “Female Operatives Are Preferred”: Two Stories of Women in Manufacturing

- The Changing Nature of Sewing

- Collecting Mobility: Insights from Hagerty

cars, Ford Motor Company, Made in America, Henry Ford Museum, Model Ts, manufacturing

Portrait of Aloha Wanderwell Baker, 1922-1928, THF274629

Secretary. Driver. Mechanic. Lecturer. Explorer. Cinematographer. Filmmaker. All of these job titles, and many more, were held by one extraordinary woman in the 1920s. Her global adventures, visiting more than 40 countries on four continents, earned her the moniker, “The World’s Most Widely Traveled Girl.” And throughout it all, Aloha Wanderwell Baker challenged societal norms, built a career for herself, and created an inspiring legacy of curiosity and resourcefulness.

The young woman who would become Aloha Wanderwell Baker was born Idris Galcia Hall in Winnipeg, Alberta, Canada, in 1906. After her father was killed in action at the Third Battle of Ypres during World War I, Idris’ mother decided to move with both of her daughters to Europe. Young Idris, enrolled in a French convent school, longed for adventure and world travel. According to her memoir, Call to Adventure!, she was a girl who, “desired to sleep with the winds of heaven blowing around her head, and who preferred the canopy of stars and the Mediterranean moon to the handsome but dust-catching and air-repelling draperies of the school furnishings.” With these yearnings, Idris’ time at the school would not be long.

Captain Walter Wanderwell Business Card, THF274644

In 1922, young Idris’ future would be forever changed when a traveler known as Captain Walter Wanderwell arrived in Nice, France. Cap, as he was more commonly known, was Polish-born Valerian Johnannes Pieczynski. In 1919, Cap and his wife Nell founded the Work Around the World Educational Club, or WAWEC, to promote world peace, provide educational opportunities, and monitor global disarmament. To accomplish these goals, Nell and Cap competed in a global driving race, the winner being the team to rack up the most miles. Along the way, the teams would sell promotional pamphlets, host lectures, and screen their adventure films as a means to raise money and educate the public. Corporate funds were also sought, such as Cap contacting Henry Ford in 1922 about purchasing the negatives for educational films that were shot. By the time Cap wrote that letter to Ford, he and Nell were physically separated, in Europe and North America, and essentially separated in their marriage.

Correspondence between Ford Motor Company and Walter Wanderwell, 1921-1922, THF274639

And so it was in Nice, in October 1922, that Cap and Idris’ paths would cross, and her future would forever be changed. In her memoir, she talks about seeing an advertisement for Cap’s lecture in the local newspaper, sneaking out of school to attend. Utterly inspired and captivated by the images she saw, young Idris spoke with Cap afterward. During the conversation, he mentioned his need for a new expedition secretary. The Nice newspaper also carried an ad for this position with the headline, “Brains, Beauty and Breeches-World Tour Offer for Lucky Young Woman.” Going against contemporary norms, the woman who accepted this position would forego skirts for breeches, promise not to marry for at least three years, and be prepared to rough it through Africa and Asia. At the age of 16, Idris, with her mother’s permission, joined the Wanderwell Expedition and became known as Aloha Wanderwell.

Postcard, Wanderwell Expedition 1921-192?, THF274627

Between October 1922 and December 1923, the Wanderwell Expedition crisscrossed Europe in their Model Ts. Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Poland - all were visited, some multiple times. Along the route, Aloha learned the skills that would carry her career into the future. After leaving the tour for a few months due to an argument with Cap, Paris became a bore and Aloha longed to be back on the road. She tracked the expedition down in Egypt, and met up with the crew in March 1924.

Aloha Wanderwell Arrives at the Sphinx, 1924

After Cairo, the expedition wound its way through the Middle East, then sailed on to Pakistan and India. They covered more than 2,200 miles before sailing to Malaysia. The travelers then made their way up to Cambodia, where they marveled at Ankor Wat, and then went on to Singapore, Hong Kong, and Shanghai. They went up through Tientsin, Peiping, and Murkden before being granted visas to travel to Siberia. Japan was visited after Russia, and then the Wanderwell Expedition sailed for North America.

Driver Aloha Wanderwell on the Hoist Lifting Her Ford Model T from Aboard Ship, Shanghai, China, 1924,THF96385

They made landfall in Hawaii, where Cap filmed Aloha next to the Halemaumau volcano. When the expedition arrived in California, Cap left for a few weeks, traveled to Florida, and legally divorced Nell. Upon his return to California, Cap proposed to Aloha, and they wed in April 1925. Over the next few months, they drove throughout the American West and Midwest, ending up in Detroit that August and ultimately ending in Florida. Their first child, a son named Valri, was born there that December.

Captain Walter Wanderwell Filming Aloha Wanderwell on the Edge of Kilauea Volcano, 1924, THF274631

In 1926, the Wanderwells were traveling through Cuba, Canada, and the northeastern United States before they sailed for South Africa, where Aloha reunited with her mother and sister. There, in April 1927, Aloha gave birth to the couple’s second child, a son named Nile. Three weeks later, with Aloha’s mother caring for the children, the expedition left again to traverse the eastern coast of Africa. North they drove, through Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya, where on October 13, 1927, Aloha celebrated her 21st birthday in Nairobi. This journey ended in France, where the Wanderwells reunited with their children and the family returned to the United States. The film documenting these journeys, With Car and Camera Around the World, debuted in 1929.

Aloha Wanderwell Driving Car between Limpopo River and Sabe River, Mozambique, 1927, THF274633

The following year in 1930, Cap and Aloha were traveling to Brazil, visiting the Mato Grosso region in an effort to search for lost British explorer Lt. Colonel Percy Fawcett. Flying to the interior of the Amazon rainforest, the Wanderwells’ plane had to make an emergency landing, ending up in the territory of the Bororo tribe. Over the next month, Cap and Aloha befriended them, and when Cap left to obtain replacement parts, Aloha stayed with the Bororos and filmed her experiences. The resulting film, Flight to the Stone Age Bororos, remains part of the Smithsonian’s anthropological film library to this day. Another film focusing on this trip, The River of Death, can be viewed through the Library of Congress.

The next Wanderwell expedition was to be an ocean voyage throughout the Pacific. A yacht, The Carma, was being fitted out for this journey, although it was not to be. In December 1932, Captain Wanderwell was shot and killed on board, a case that remains unsolved. The year after Cap’s death, Aloha married former WAWEC cameraman Walter Baker. The couple continued to travel and film their adventures. Over the years, the travel grew less, but Aloha continued to give lectures and presentations about her adventures. Aloha Wanderwell Baker passed away in Newport Beach, California, in 1996, about a year after Walter.

Aloha’s films, photographs, and writings have allowed later generations to learn of this extraordinary woman who followed her passion. In an age where women were expected to wear dresses and work within the home, she wore breeches and traveled the world. Aloha cultivated skills in jobs that were traditionally reserved for men, and used that knowledge to further her career. She turned a desire to be out in the world into a lifetime of learning and exploring. And in the end, her desire to “sleep with the winds of heaven blowing round her head” drove her to follow her heart, keep an open mind, and learn from the world.

Janice Unger is Processing Archivist at The Henry Ford.

Source:

Wanderwell, Aloha. Aloha Wanderwell Call to Adventure!: True Tales of the Wanderwell Expedition, First Woman to Circle the World in an Automobile (Touluca Lake, California: Nile Baker Estate & Boyd Production Group, 2013), pages 21-26.

roads and road trips, cars, Model Ts, archives, travel, by Janice Unger, women's history

A Significant Car on an Important Roster

1927 Ford Model T Touring Car, The Fifteen-Millionth Ford. THF135450

Beginning today through April 9 we're honored to have our 1927 Ford Model T Touring Car, the fifteen-millionth Ford, on view at the National Mall for the 2018 Cars at the Capital event. The Historic Vehicle Association has selected our T for inclusion on its National Historic Vehicle Association Register. The 15 Millionth Model T joins impressive roster this year; other vehicles being added to the list include a 1984 Plymouth Voyager (the first Chrysler Minivan), a 1968 Ford Mustang Fastback (used in the iconic chase scene in the 1968 film Bullitt), a 1985 Modena Spyder California (featured in the 1986 movie Ferris Bueller's Day Off), and a 1918 Cadillac Type 57.

Henry Ford and Edsel Ford with the Fifteen-Millionth Ford Model T on the Last Day of Model T Production, May 26, 1927. THF118798

Although the 1927 Model T looked different from the original 1908 Model T due to many styling changes, the basic elements that made the Model T a technological innovation and cultural phenomenon - a simple 4-cylinder engine, planetary transmission, the limited color choices, and a flexible and strong chassis - were still there but were now liabilities in the automobile market. Consumers were no longer satisfied with a basic, dependable car. Americans demanded faster cars with smoother rides and more amenities. By the mid-1920s, it was obvious to almost everyone at Ford that the Model T's time had passed. Henry Ford, however, retained his firm belief that the Model T was all that anyone would ever need. In an attempt to check declining sales, Ford engineers incrementally modernized the car, introducing options such as electric starters, manually operated windshield wipers and body color choices. (Famously, black as the only color offered from 1914 through 1925.)

None of these ploys, however, allowed the Model T to compete with Chevrolet and Dodge Brothers cars that offered heaters, automated wipers, and a more comfortable ride - all at a comparable price.

When production of the Model T ended in May 1927, Henry Ford's "Universal Car" had introduced the world to the idea of personal mobility and transformed where and how we lived.

Take a look at the car getting ready to head to Washington, D.C., in this video.

cars, Greenfield Village, Henry Ford, by Matt Anderson, Ford Motor Company, Model Ts

Saved by Model T’s

As cars became more widespread during the early 20th century, mechanized vehicles began to replace horses and wagons in wartime. While tanks were tested on the battlefield during World War I, there was also a need to remove wounded soldiers from the front quickly, safely, and efficiently. Ford Motor Company’s Model Ts were light, economical, and easy to operate, which made them perfect for this need.

We’ve just digitized dozens of photographs and drawings showing these innovative World War I–era Ford Model T ambulances, including this October 1918 demo picture, with the wartime message “On to Berlin” visible on the shoe soles of the “patient.”

Visit our Digital Collections to browse more photographs and technical drawings of Model T ambulances.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Strategy Manager, Collections & Content at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Europe, 1910s, 20th century, World War I, Model Ts, healthcare, Ford Motor Company, digital collections, cars, by Ellice Engdahl