Posts Tagged space

Model Maker: Photographer Dan Winters

Dan Winters surveys a shifting landscape—his own backyard. On a mid-August morning, the 59-year-old photographer, author, and filmmaker is in the kitchen of his Austin, Texas, home, detailing the impending relocation of his studio and workshop (headquartered in a converted post office, general store, and Texaco station 25 miles south in unincorporated Driftwood) to just steps from his front porch. Anyone who has worked with Winters—presidents, astronauts, publishers of the country’s most influential publications—could grasp the challenge, given Winters’ lifelong accumulation of equipment, archives, and personal collections, which range from apiaries (beehives) to pieces of Apollo spacecraft.

The shuffling of workspaces feels natural, almost expected, given the rotational history of his surroundings. Winters’ home, which he; his wife, Kathryn; and son, Dylan, moved to from Los Angeles in 2000, was built in downtown Austin in 1938 and later transported to this quiet enclave on the north side of town circa 1975. Their detached garage will soon supplant the Driftwood studio. It was originally Winters’ model-building workshop, but that migrated a decade ago to a pitched-roof room on the second floor. The model shop is a place of refuge cocooned in paint sets, kit parts, and books on the artistry of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Dan Winters’ first serious profession was that of a motion picture special effects model builder. He still builds miniatures today, finding the act of creating for the sake of creating rewarding. / Photo by Dan Winters

Winters vividly recalls the first model he ever built (a British SE5a biplane), around age 6, with his father, Larry Winters—a welder from Ohio who moved the family to Ventura, California, in 1959. “I would ask him to draw me something, an airplane or a rocket, and it would be on the breakfast table when I’d get up in the morning for school,” Winters said from his own breakfast table. “He would also make little spaceships out of wine corks and put screws in them or paper clips for skids. He’d leave them as little surprises.”

Seeing Possibility

Model-building has been a constant in Winters’ life. “When you start a model,” he explained, “the only thing that exists is your intent and whatever tools and materials you need. You work through the thing, create it, and then it exists. You will it into being. There’s an unbelievable satisfaction in that. In the ability to see what the model is going to be before it gets to a point of unification.”

Growing up, Winters remembers the yard on the working farm where he was raised as always strewn with spare parts, and he was often tasked with repurposing them. “The engine in our Volkswagen threw a rod, and we had to rebuild the whole thing,” he recalled. He assisted his father on nights and weekends, staving off resentment for missing idle time with his friends. “I remember the weekend we put the motor back in. We had it on a jack, and my dad slid it in, and I had to balance it until it speared the spline of the transaxle. He got in and pushed the clutch and it started up—I mean, right up. We took it for a drive, even though the bumper and deck lid were off. I remember driving down the street and reflecting on what it took to do that. As a kid, it was way out of my wheelhouse. But seeing that it was possible to do that was massive.”

In 1978, Winters’ father drove his 16-year-old son 50 miles to Van Nuys to visit Apogee, a special-effects company operated by John Dykstra, the Oscar-winning effects supervisor on Star Wars. Winters had cold-called Steve Sperling, who ran the office, and sent several photographs of his model spaceships by mail. A tour with Grant McCune, chief model maker on Star Wars and Battlestar Galactica, was arranged. As Winters wrote in his 2014 book, Road to Seeing, “Once inside, it was surreal to see the same model shop firsthand that I’d studied in dozens of photographs published in movie magazines. I was captivated by the artistry I witnessed at every turn…. I cannot describe the profound inspiration and affirmation this visit gave me.”

Road to Seeing by Dan Winters explores his journey to becoming a photographer and significant moments in his career.

In the months that followed, Winters’ mailbox remained packed with special-order plastics, and his fleet of scratch-built spaceships grew. The photos of his progress eventually led two Apogee veterans to recommend him for employment at Design Setters, an effects house in Burbank. Through a work-experience program during his senior year, Winters attended two classes in the morning, then drove to the San Fernando Valley to build models, including one for the Neil Young film Human Highway. It was a creative utopia disguised as a pass/fail.

This portrait of actor Denzel Washington, seated in a set singlehandedly constructed by Dan Winters and published in the New York Times Magazine in 1992, was an inflection point in Winters’ career, opening the door to decades of world-class editorial and portrait work. / Photo by Dan Winters

After attending college at Moorpark, studying abroad in Munich, and assisting for photographer Chris Callis in New York City, Winters began incorporating his skills as a model builder and production designer into his portraiture, creating fictitious worlds unique to each image. An assignment to photograph Denzel Washington for the New York Times Magazine in 1992 was instrumental. Winters stayed up through the night and singlehandedly built a forced-perspective set that evoked the rural outposts documented by photographer Walker Evans during the Depression. The set also emphasized the body position of a seated Washington, whose hands were resting against his dark suit, causing his fingertips to pop. The secret, in a sense, was the human touch.

Winters’ subjects have included Ryan Gosling (above), the Dalai Lama, Tupac Shakur, Helen Mirren, and Fred Rogers, who, according to Winters, “treated the photo shoot sacredly.” He’s also photographed two presidents, George W. Bush and Barack Obama; his portrait of Obama is featured prominently as the back jacket of the president’s memoir, A Promised Land. / Photo by Dan Winters

Another World

This approach carries through Winters’ latest and most immersive project, the film Tone, which he wrote, directed, and photographed. It’s a love story set in a dystopian future where a laborer—the eponymous Tone, whose vocal cords have been stripped by a surveillance state—returns to Earth from Mars and helps heal another broken soul. At nearly 40 minutes, the project far exceeds the scope of Winters’ previous short-subject documentaries and music videos, and visualizing both the earthbound and cosmic elements of the story demanded extensive model and miniature work.

The majority of those Mars miniatures, both piecemeal and whole, still reside in Winters’ Driftwood studio. (Before driving from his home for a studio tour, he cautioned not to crush a box of spare plastics on the car seat, which a hobby shop owner had recently reserved for him. It was an F/A-18C Hornet kit affixed with a handwritten Post-it note that read: WINTERS DAN PARTS GIFT.) Built in 1903 as a post office and general store, the sandstone building in Driftwood expanded in 1942 to accommodate a feed store. A subsequent owner extended that addition, turning a water cistern out back into an interior structure, surrounded by closets, one of which Winters converted to a darkroom. The facade is adorned with a defunct fire-engine-red Texaco gravity pump, occasionally confusing gas-strapped passers-by on the highway.

| A Photographer’s Thoughts on a Photograph |

Portrait of Charles Batchelor, "First Photograph Made with Incandescent Light," 1880 / THF253728 |

| “As a practitioner of the craft of photography, I frequently employ the use of artificial light when making my photographs, the distinction being that the light emanates from a manmade source and not from the sun. |

Inside, Winters stands beside a bay of humming computer monitors with a Topo Chico. The cold bottle of sparkling water is perfect for slaking thirst and, as tradition holds, providing the next building block in a backyard pile of empties he’s dubbed Mount Topo. Through hundreds of annual deposits, the glass mountain now hosts a rotating colony of pill bugs, snakes, silverfish, and eleodes (beetles). It’s another world within worlds on the studio grounds, where nature and Winters’ collection of artifacts from nearly two centuries of photographic history meet the realities of an increasingly digitized future.

The encroachment of the elements proved calamitous in 2020, when winds clocking 75 mph tore at the metal roof and rainfall destroyed thousands of negatives in storage lockers below. While taking solace that well over a million negatives were safe, including those amassed from anonymous collections he’d found at junk stores and paper-goods shows, the incident nonetheless prompted the decampment for his Austin backyard, where proximity alleviates the increasing sense of vulnerability.

With another Topo tossed to the beetles out back, Winters begins detailing the international origins of the books on the shelves lining the original exterior wall of the post office. It called to mind the 1931 essay “Unpacking My Library,” in which German theorist Walter Benjamin wrote, “I have made my most memorable purchases on trips, as a transient.… How many cities have revealed themselves to me in the marches I undertook in the pursuit of books!”

Winters settles on Photography Album 1, edited by Pierre de Fenoyl, purchased at 23 while biking across Australia. “There’s amazing work in it, work that made me feel like photography was boundless,” Winters said. “I was riding from Sydney to Adelaide, and I had two panniers on my bike for storage. I rode that book for 1,300 miles, in a brown paper bag. I still have the bike; it’s at the house.” A casual flip through the book revealed a preserved leaf tucked inside. “We want to have a memory,” Winters added. “Certain objects will anchor us to a place and time.”

Dan Winters considers his desk, an old drafting table, the anchor of his studio. Littered with objects collected over time, he said of this space, “Sitting at the desk provides a connection to my history.” / Photo by Dan Winters

The undisputed anchor of the studio is Winters’ work desk, an old drafting table festooned with his full range of interests. “Sitting at the desk provides a connection to my history,” he said. “I’m inspired by the intrinsic value of these objects. Some have historical significance, certainly, and some are significant to me and my own path in life. Oftentimes they’re just beautiful objects I like to contemplate. One of the drawbacks of the collection is I feel it would be pretty quickly marginalized by whoever was settling my estate. At first glance, it probably looks like junk.”

According to theorist Benjamin, “the most distinguished trait of a collection will always be its transmissibility.” Winters senses the necessity of cataloging these objects in the moment and imparting their meaning. There’s the National Supply badge that belonged to his grandfather, whose company made transmissions for Sherman tanks. Or a rivet from the Golden Gate Bridge, flecks of international orange paint still visible. (Ironworkers presented the rivet ceremoniously to Winters after a photo shoot.)

| Lost in Space | |

Photo by Dan Winters |  Photo by Dan Winters |

| Among Dan Winters’ desktop mementos are two pieces of equipment from the Apollo program: a pressure transducer (left above) and an RCS check valve assembly, still bagged (right above. Both were procured from a Los Angeles scrap dealer who capitalized on the closure of a Van Nuys plant operated by Rocketdyne, manufacturer of the Saturn V engines. The keepsakes have remained within reach ever since. | |

There’s also a swab attached to a wine cork, which is in fact a vital tool, one that facilitated a series of portraits for National Geographic that quickly became among Winters’ most widely seen images. Published in May 2021 and intended to draw attention to World Bee Day, the subject was actress Angelina Jolie covered in bees. Before the shoot, Winters and friend Konrad Bouffard contacted Ronald Fischer, an entomologist now in his 90s, who was “bearded” in bees for an iconic Richard Avedon portrait in Davis, California, in 1981. They also reached Avedon’s on-set beekeeper, who still had the cork swab he’d used to dot Fischer’s skin with queen-bee pheromone, thus attracting a swarm. As a lifelong beekeeper, Winters was honored to use the very same swab for his shoot and to be told he could keep the cork among his treasures.

It was hard not to draw a line to the cork-and-paper-clip spaceships Winters’ father left for him in the mornings, the ones that inspired him both to build and to collect. Asked if a cork ship was docked on his desk, Winter was convinced, though he couldn’t pinpoint one. “I know I have one in these boxes,” he said, sifting through cardboard stacks. He reminded himself to check later. For now, the day was still young, and the sun was out. In the shadow of Mount Topo, this message in a bottle would remain open, awaiting its cork.

James Hughes is a writer and editor based in Chicago. This post was adapted from an article in the January–May 2022 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Texas, The Henry Ford Magazine, space, photography, photographs, movies, making, California, by James Hughes, books, 21st century, 20th century

Neil Armstrong: Reluctant Hero

Neil Armstrong visited Greenfield Village on August 16, 1979, and graciously posed for several photographs, particularly near the Wright Brothers’ Home and Cycle Shop. / THF128243

Watching the moon landing on TV on July 20, 1969, was a defining moment for most baby boomers. I know it was for me. My brothers and I were glued to the TV set for hours, hanging on to every word uttered by broadcast journalist Walter Cronkite, waiting for the exciting moment that the Lunar Module Eagle would land on the moon and its crew members would take their first steps into uncharted territory.

Photograph of the TV broadcast of the moon landing, July 20, 1969, with TV viewers dimly reflected on the screen. / THF114240

Three Apollo 11 crew members—Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr., and Michael Collins—embarked on this mission on July 16 and returned safely to earth on July 24. In between, each crew member contributed his utmost to the tasks at hand. But one name eternally sticks out—Neil Armstrong, the mission’s commander. As commander, he accepted his role as spokesperson for the crew and the mission. And, as commander, he became the first man to step on the moon, voicing the now-immortal words, “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.” After that time, he relentlessly shunned the limelight and hated being singled out. When Armstrong passed away in 2012, his family released a statement that reinforced these sentiments: “Neil Armstrong was a reluctant American hero who always believed he was just doing his job.” Yet, like it or not, he was—and will forever be—singled out as the “first man.”

Artist Louis Glanzman captured the spirit of the momentous occasion for the July 25, 1969, cover of Time magazine, despite having no real photographs to reference (none were available yet and, in fact, no photographs of Neil Armstrong were ever taken on the moon). It became one of Time’s most popular covers ever. / THF230050

Neil Armstrong was from Ohio—as I am. I have always been proud of that connection. In the 1990s and early 2000s, when my daughter was young and we would often drive down I-75 to visit family members in Dayton, we would stop at the Armstrong Air & Space Museum (founded in 1972)—located right at the freeway exit for Armstrong’s hometown of Wapakoneta. There we would enjoy viewing personal artifacts of his, reliving the story of the Apollo 11 mission, and reacquainting ourselves with the timeline of all the missions leading up to and following that one.

So, when the opportunity arose to write a blog post about Neil Armstrong, I enthusiastically volunteered. I figured I would enjoy reading up on him again. This time around, however, I particularly looked for insights into what made him that reluctant hero.

Armstrong was born in a farmhouse about six miles from the small town of Wapakoneta, Ohio, on August 5, 1930. He didn’t actually live in Wapakoneta until he was 14 years old. Because his father was an auditor for the state of Ohio, his family often moved around—in fact 16 times before they finally settled in Wapakoneta! Other small Ohio towns—like Upper Sandusky and St. Marys—were just as influential in shaping his character. As a boy, he was considered calm, serious, determined, and always on task.

Interior of a Ford Trimotor during a passenger flight, 1929. / THF116296

Being an astronaut was not Neil Armstrong’s great ambition in life. He wanted to fly airplanes, and wistfully envied earlier pilots like Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart with their record-setting flights. When he was only six years old, he thoroughly enjoyed the ride he took on a Ford Trimotor (his father was downright terrified). (For more on Trimotors, see this expert set.) A few years later, he began building and flying model airplanes; in fact, he filled his bedroom with them. He read countless books and magazines about airplanes. He also worked various jobs to earn money to take flying lessons. At only 15, he earned his pilot’s license and made his first solo flight soon after.

Neil Armstrong was different from many other airplane pilots and, later, astronauts in that he was not only interested in flying, but also in learning how planes were built and how to make them more efficient, faster, better. So, he decided to study aeronautical engineering, attending Purdue University on a Navy scholarship.

Armstrong’s college years were interrupted by his being sent to fight in the Korean War. He was assigned to Fighter Squadron 51, flying small jets off an aircraft carrier to bomb enemy bridges and railroads and to scout areas where other planes would attack later. After college, Armstrong flew high-speed, high-altitude experimental airplanes at Edwards Air Force Base in the Mojave Desert, California—not because he loved speed (as many other test pilots did), but because he wanted to use planes as tools to gather information and solve problems.

Armstrong loved this work, but in 1962 he switched gears and applied to become an astronaut. Some say this was because of his need to make a dramatic lifestyle change after the tragic death of his two-year-old daughter. But he himself claimed, “I decided that if I wanted to get out of the atmospheric fringes and into deep space work, that was the way to go.”

Either way, before long, Armstrong was chosen to become one of the so-called “New Nine”—that is, the second group of men (women were not allowed to become astronauts until 1978) that NASA picked to fly missions to outer space. (For more on the initial Mercury Seven astronauts, see this blog post.)

Before the “New Nine,” there were the Mercury Seven, the first seven astronauts chosen by NASA to attempt to place a man in space through a program known as Mercury. Here they are posing in their space suits for this circa 1963 trading card. / THF230119

That was seven full years before Armstrong became a household name with the Apollo 11 mission. What did he do during all that time? In fact, a great deal needed to be figured out and perfected if there was to be any hope of meeting President John F. Kennedy’s vision to land a man on the moon before the end of the decade. Armstrong spent much of his time practicing, training, and undertaking the many tasks that prepared him and others to fly to outer space and attempt a moon landing. During these years, Armstrong also willingly talked to members of the media, not only because they never seemed satisfied with NASA’s updates, but also to help allay negative public opinion about the government’s focus on the space program when so many domestic issues seemed more pressing.

Many people felt that such pressing issues as poverty, Civil Rights, and the war in Vietnam (as reflected by this 1968 protest poster) should take precedence over the space program. / THF110904

Meanwhile, Armstrong patiently waited his turn—like the other astronauts—to participate in a real mission to outer space. He finally got that turn in March 1966, when he was assigned to command NASA’s 14th crewed space mission, Gemini 8—with the goal to “dock” or connect with another satellite already in space. In 1968, he was also named the backup commander for the Apollo 8 lunar orbit mission (but did not go on that mission).

During that time, Armstrong repeatedly practiced with the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV)—the prototype module for landing men on the moon. The LLTV was an ungainly, unstable wingless aircraft, powered by a turbofan engine, which took off and landed vertically. It was highly experimental and extremely dangerous. As Buzz Aldrin later remarked, “…to train on it properly, an astronaut had to fly at altitudes of up to five hundred feet. At that height, a glitch could be fatal.”

Armstrong faced constant risks and dangers in his career as an airplane pilot and then as an astronaut—including flying 78 missions in the Korean War; piloting the world’s fastest, riskiest, most experimental aircraft; and encountering close calls while commanding Gemini 8 and while practicing on the LLTV. But he never panicked. He concentrated on the tasks and remained cool under pressure. His mind was always focused on analyzing and solving the problems, then on moving forward.

And that is exactly why he was chosen to command Apollo 11—the space mission that would finally attempt a landing on the moon. As Chris Kraft, NASA’s director of flight operations at the time, explained, “Neil was Neil. Calm, quiet, and absolute confidence. We all knew that he was the Lindbergh type. He had no ego. He was not of a mind that, ‘Hey, I’m going to be the first man on the Moon!’ That was never what Neil had in his head."

Neil Armstrong brought to the Apollo 11 mission all of his training, practice, and knowledge. His ability to keep calm under pressure particularly came in handy when he and Aldrin landed the Apollo’s Lunar Module Eagle onto the moon’s surface with only 20 seconds of fuel remaining.

Which brings us back to the moment when I—along with about 500 million other people—sat on the edge of my seat and watched on TV as the Eagle landed, and, several hours later, as the Eagle’s hatch opened, as Neil Armstrong wriggled out and began to descend the ladder toward the moon’s surface, and as he took his first step on the moon.

Neil Armstrong took this famous photograph of Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin on the moon. His own reflection can be seen in Aldrin’s helmet. / THF56899

The moon landing was considered a success. Americans were ebullient as they celebrated the Apollo 11 astronauts’ achievements, with only months to spare before the decade ran out. The three Apollo 11 crew members were honored and celebrated for months afterward.

This set of tumblers, commemorating the Apollo 11 space mission, depicts such iconic images as the Lunar Module Eagle and Neil Armstrong’s first step on the moon. / THF175132

But most of the adulation, it seemed, was directed at Neil Armstrong. He even received the Medal of Freedom, the highest award the U.S. government bestows on a civilian. But he never liked the attention. He felt he did not deserve the fame and always attributed the success of the mission to the entire team of people who had made the dream of reaching the moon possible. Ever modest, he once tried to argue, “I was just chosen to command the flight. Circumstance put me in that particular role.”

This button would have likely been proudly worn by someone attending a public celebration of the Apollo 11 astronauts. / THF189959

In the end, I believe that Neil Armstrong should be remembered for so much more than being the “first man.” For his modesty, his quiet humility, over to advance the course of human progress, he modelled values and behaviors for which we can all strive. He may have been a reluctant hero, but these qualities, to me, are exactly what make Neil Armstrong heroic.

That, and the fact that he was from Ohio (just kidding)!

The author posing with a statue of Neil Armstrong (with model airplane fittingly in hand) on a bench in front of the Armstrong Air & Space Museum in Wapakoneta, Ohio, November 2021. / Photo courtesy of Donna Braden.

Donna R. Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Heroes of the Sky

- Modernizing the Mail

- 1928 Ford 4-AT-B Tri-Motor Airplane, "Floyd Bennett," Flown Over the South Pole by

- Richard E. Byrd

- A Stunt-Flying Aviatrix

Ohio, 20th century, 1960s, travel, space, popular culture, flying, by Donna R. Braden, aviators, airplanes

Cover of "Habitability Study, Earth Orbital Space Stations," 1968 / THF109188

In 1967, late in his storied career, industrial designer Raymond Loewy and a small team were contracted as NASA “space habitability” experts, producing a series of reports that focused on long-duration missions and the problem of how to exist as a “whole human” in outer space.

These reports acknowledged the restrictive parameters of spacecraft interiors yet stressed the ability of human-centered design to boost crew morale. They considered sleeping arrangements, modular storage, communal dining, mental decompression spaces, and entertainment in zero gravity—including a “one man theatre” helmet and a weighted “space dart” game.

"Habitability Study, Earth Orbital Space Stations,” Figure 6B, page 15B / THF701089, detail from THF701085

Loewy’s plans underscored the most “human” of all space travel design problems: the intake of food and disposal of body waste. The images above and below may look quaint to us now, but it is important to note that at the time that Loewy was considering how an astronaut might eat tomato soup in space, plastic squeeze-tube packaging was still considered experimental. As for the inevitable issue of waste collection, Loewy provided several ergonomic space toilet designs, underlining bathroom privacy for crew members.

"Habitability Study, Earth Orbital Space Stations,” Figure 55, page 112 / THF701090, detail from THF701086

While not all of Loewy’s ideas were adopted, several suggestions were implemented in the Skylab space station, including the biggest astronaut perk of all—a window to gaze at the stars while floating in space.

Visit our Digital Collections to browse selected pages and images from one of Raymond Loewy’s habitability studies.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communications and Information Technology at The Henry Ford. This post was adapted from an article in the January–May 2022 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

20th century, 1960s, The Henry Ford Magazine, space, design, by Kristen Gallerneaux

NASA’s first attempt to land a spacecraft on the moon was the unmanned Ranger 3, launched on January 26, 1962.

THF141214

Ranger 3 carried a 25-inch “Lunar Facsimile Capsule,” developed by Ford Motor Company’s aerospace division, Aeronutronic, located in Newport Beach, California.

THF141217

Aeronutronic described the capsule as “a 300-pound ‘talking ball’ containing a seismometer to record moon quakes, temperature recording devices and other instruments.” The data these instruments collected about surface conditions on the moon would be important for planning later, manned missions.

Testing began in 1960. The capsule would need to withstand the extreme heat of lunar day and the extreme cold of lunar night. A special vacuum test chamber was used, which could be cooled by liquid nitrogen to minus 320 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 196 degrees Celsius).

THF141211

The small capsule was encased in an “Impact Limiter,” a larger ball made from carefully cut segments of balsa wood, which would protect the capsule and its delicate instruments from damage during its rough landing on the moon.

THF700675

The lunar landing sphere was mounted on a retrorocket that would decelerate the spacecraft to 80–100 mph (130–160 kph) as it impacted on the moon.

THF700681

The retrorocket was made from “Spiralloy,” a glass fiber composite. The retrorocket itself weighed only 15 pounds (7 kilograms).

THF700666

Unfortunately, Ranger 3 malfunctioned and flew past the moon on January 28, 1962.

THF700679, detail

Aeronutronic built two more lunar capsules, launched later in 1962 aboard Ranger 4 and Ranger 5. Ranger 4 was destroyed when it crashed into the far side of the moon on April 26, 1962. Ranger 5 missed the moon on October 21, 1962. It joined Ranger 3, trapped in orbit around the sun, where it remains to this day.

Following these failures, the Ranger spacecraft was completely redesigned for later missions in 1964–1965. These spacecraft would no longer carry a lunar landing sphere; instead, they would photograph the moon as they approached. Ranger 7, Ranger 8, and Ranger 9 successfully took over 17,000 thousand high-resolution photographs of the lunar surface.

Jim Orr is Image Services Specialist at The Henry Ford. This post is based on a July 2019 presentation of History Outside the Box.

California, 20th century, 1960s, space, History Outside the Box, Ford Motor Company, design, by Jim Orr

Suits for the Stars: Spacesuits of Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Cocooned within 21 layers of synthetics, neoprene rubber, and metalized polyester films, Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin was well protected from the airless moon’s extremes of heat and cold, deadly solar ultraviolet radiation, and even the off chance of a hurtling micrometeorite. / Photo by Neil Armstrong/NASA

Cocooned within 21 layers of synthetics, neoprene rubber, and metalized polyester films, Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin was well protected from the airless moon’s extremes of heat and cold, deadly solar ultraviolet radiation, and even the off chance of a hurtling micrometeorite. / Photo by Neil Armstrong/NASA

It’s possibly the most recognizable image in all of human history: Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the moon, his left arm drifting up as if checking the time during a stroll through the park.

The photo sticks in the imagination more than any image of sleek rockets on the launchpad or metallic modules landing on an inhospitable world. Perhaps it’s the casual, individual bravado oozing off Aldrin’s puffed-up frame that truly captures the essence of humans pushing past the ultimate boundary: space.

And yet the spacesuit is rarely the star of the human spaceflight epic. Which is a shame, since this was the most intimate component of the engineering endeavor that landed man on the moon 50 years ago—intimate also because the surprising winner of NASA’s spacesuit contract was a spinoff of Playtex, the underwear manufacturer which still makes items from bras to feminine products to this day.

Playtex made everyday women’s girdles like those shown in this ad before making an unlikely jump to producing clothing for space travel to the moon in the 1960s. / Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“The suits that other companies provided were stiff, they were bulky, they couldn’t fit the narrow confines of the mission parameters,” said Nicholas de Monchaux, professor of architecture at University of California Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design and writer of a deeply researched book called Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo.

At the core is the idea of the “human factor,” often overlooked by engineers in their quest to reach the lunar surface. The Saturn V rocket and the lunar module were exquisitely engineered, with sharp, clean lines governed by the unchanging forces of physics: thrust, gravity, air resistance. But the same equations are blurred when dealing with the human form. “The human body doesn’t operate from first principles,” said de Monchaux.

In the race to win the initial suit contract, companies such as David Clark Company, which made the Mercury mission spacesuits, and Hamilton Standard, a division of conglomerate United Aircraft, produced concepts informed by their decades-long experience with high-altitude pressure suits. These options proved much more difficult to maneuver than the suit produced by ILC Dover, the Playtex spinoff whose patented “convolutes” included rubber identical to that filling Playtex’s girdle molds, as well as nylon tricot and webbing taken from the supplies feeding its brassiere assembly lines.

The Apollo spacesuit designed by ILC Dover and worn on the moon had 21 layers, 20 of which were created with synthetics made by chemical giant DuPont. Familiar household names like nylon, Lycra, and Teflon were found in various layers, a fact DuPont proudly advertised at the time.

In 1966, events came to a head when a new ILC spacesuit had to compete once more against prototypes from Hamilton Standard and David Clark. Test subjects using the competing suits had trouble moving around, operating switches, and fitting in and out of the mock landing module. Imagine if Aldrin and Neil Armstrong had touched down successfully on the moon only to not fit through the hatch to step on the surface!

Though each competing suit was custom fitted, only the 21-layer ILC Dover soft suit was sewn by hand by a hotshot crew of the best seamstresses taken from Playtex’s sewing floor—eschewing paint-by-numbers engineering in favor of highly personalized, artisanal craftsmanship. Each spacesuit created by the ILC Dover team bore a laminated photograph of the astronaut it belonged to in order to create a connection to the person whom they were literally keeping alive with their craftsmanship.

Arlene Thalene of ILC Dover inspects a spacesuit’s mylar insulation layers. / Photo courtesy of ILC Dover, LP

Their knowledge, gained by fashioning bras and girdles for women’s activewear, proved indispensable to creating a superior product. The material itself was co-opted: “The rubber that made the suit was literally from the same tank that was, originally at least, supplying the girdle-making that had made Playtex’s fortune,” said de Monchaux.

ILC Dover employee Velma Breeding installs a bladder into a boot. / Photo courtesy of ILC Dover, LP

The ILC Dover suit bested the others in official NASA tests, but the systems-engineering bureaucracy of the Apollo program was still skeptical of an untested spinoff holding such a critical contract. When again faced with competition for the last phase of Apollo’s missions (numbers 14-17), the ILC Dover team even resorted to filming a test subject playing football in a pressurized suit for several hours. “And, as became clear on watching the films, the suited subject’s attempts were at the very least equivalent to those of an engineer in shirtsleeves and slacks who joined him on the field,” wrote de Monchaux. “ILC Dover, née Playtex, had won the Apollo game.”

A composite of the final drawings from ILC Dover depicts (from right to left) an Apollo 11 spacesuit’s pressure garment assembly, a suit with its Thermal Micrometeoroid Garment (TMG) attached, and an astronaut wearing a suit with TMG outer cover, gloves, and helmet. Once securely attached to the spacesuit’s inner pressure garment, the multilayered TMG protected astronauts against micrometeoroid impacts, solar and galactic radiation, thermal conduction, and abrasion, and also provided fire protection. / Drawings courtesy of ILC Dover, LP

Dressed for Health

More than 50 years after the Apollo 11 astronauts donned their spacesuits on the moon, I’m sitting in an office at hygiene and health giant Essity’s facility in North Carolina trying to pull on what looks like your average thick knee-high black socks. Kevin Tucker, the global technical innovations manager for a division of Essity, chuckles while I struggle with the fabric as it tightens like a vice. Tucker is in charge of the company’s work with NASA to develop a compression suit for astronauts returning from space. He points out as he puts the socks away that future NASA astronauts will wear something with twice the compression power.

Essity’s bread and butter is making compression garments for people with venous and lymphatic diseases. That’s when the body has issues with pumping fluids against the pull of gravity, causing symptoms from lack of feeling in extremities to loss of consciousness. It’s something we have all experienced to some degree, said Tucker. “If you’re sick in bed with the flu and you’re lying down for a long period of time and you have to go run to the bathroom, the first step you usually take you end up on your nose.”

Astronauts also have trouble with fluid control. When they first get up into space and gravity is no longer a factor, fluids are pumped more into their torso and head. That’s why new arrivals to the International Space Station have puffy faces. After a while, the body adjusts and pumps less to accommodate the lack of gravity. But the problem rears its head again upon re-entry and the rapid reintroduction to gravity. At that point, the body’s fluid pumping is weakened, and astronauts often have to be carried out of the capsule. “This sudden rush of fluid away from the head and heart down into the legs can affect your consciousness,” said Tucker. That’s something his team is trying to change.

To help NASA, Essity is applying its expertise in designing compressive socks, sleeves, and girdles to create a compression suit future astronauts would wear on re-entry to prevent or avoid the sudden redistribution of fluids to the lower extremities upon return to Earth’s gravity. When Tucker lays out the current design on a table, it’s a crisscross of tight black fabric and a few zippers, woven in a way reminiscent of those fancy yoga pants that have sheer patterns.

Health giant Essity is currently working with NASA to create a compression suit that astronauts will wear upon re-entry to Earth. The garments, shown separately here for illustrative purposes, will prevent or avoid the sudden redistribution of fluids to the lower extremities upon return to Earth’s gravity. / Photo courtesy of Essity

It’s slated to be the first layer of gear NASA astronauts will put on as they prepare to splash down—so getting stuck as you pull on the suit is simply not an option. Another “soft” consideration is that the astronauts will have to wear these for hours in a seated, upside-down position, and tests of earlier designs irritated subjects’ bent knees. The newest version of the compression suit comes slightly pre-bent at the joint, making it more comfortable.

The Human Factor and What’s Next

The human body was not meant for space travel, and the soft problems it presents require innovative solutions with intimate knowledge of the human body. Some of those challenges (and ways suits can help) are listed below.

Vacuum: Exposed to the vacuum of space, a body’s fluids would start boiling away as the body puffs up. A spacesuit protects you—but, be warned, it will puff up, too.

Temperature: Outside the International Space Station, the temperature swings wildly from 250 to -250 degrees Fahrenheit. But with no atmosphere to transfer heat or cold, a well-insulated spacesuit keeps you comfy.

Radiation: Above the protection of the Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field, cosmic radiation is the most consistent health concern. A spacesuit provides very limited protection—as does the space station.

Lack of Gravity: Low or no gravity makes muscles atrophy, bones lose density, and fluids redistribute. NASA is working on it.

Unfortunately, the human body is not always something the engineering culture of rocket scientists takes into account. “We’re still thinking about the engineering and the propulsion systems and the vehicle, but we’re not thinking enough about the pink, squishy things that are in the middle of that vehicle,” said Diana Dayal, who did a year-long apprenticeship at the National Space Biomedical Research Institute (NSBRI). Funded by NASA’s Human Research Program, NSBRI, which closed in 2017, was NASA’s lead partner in space biomedical research and provided hands-on lab opportunities for young scientists, engineers, and physicians such as Dayal to access careers in human spaceflight.

On future, longer space missions, the human factor will be amplified. New challenges will arise from the long stint in low gravity. “The deconditioning of your bones and muscles is going to be an unavoidable problem on a three-year Mars mission,” said Dayal. “How are you supposed to send people to Mars and expect them to set up a habitat?”

Astronaut Neil Armstrong—shown here aboard the Apollo 11 Lunar Module Eagle, the first crewed vehicle to land on the moon—later quipped that his spacesuit was one of the most widely photographed spacecrafts in history. Decades later, he sent a note to the team that designed the spacesuit, complementing it and calling it “tough, reliable and almost cuddly.” You can see the “cuddly” spacesuit worn by Armstrong, held by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, on their collections website. / Photo by NASA / Edwin E. Aldrin Jr.

One of the solutions being explored is enhancing the spacesuit with an exoskeleton—essentially empowering the humans by linking them to a stronger robotic carapace. This is a good idea, but the prototype Dayal saw at NASA’s Johnson Space Center was so large and cumbersome, it was hard to imagine it on an average person.

“It’s so cool that you basically have all this circuitry that simulates nerves, but at the same time, who did you build this for? Who’s going to wear it?” They were questions posed by Dayal’s group, she said, pointing out that current designs lack sufficient modularity to adjust to different body types.

While the lessons learned in developing the soft Apollo spacesuit decades earlier may have to be revisited as we look to longer missions, it’s also an opportunity to push the boundaries of design. “All of your constraints are out the window; everything is a variable,” said Dayal. “If anything, designing for space should help us better design for Earth.”

Fedor Kossakovski is a freelance science writer and producer. This post was adapted from an article in the June–December 2019 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

The Henry Ford Magazine, making, women's history, engineering, design, fashion, by Fedor Kossakovski, space

Out There Having Fun in the Warm California Sun: Aeronutronic Systems

Looking out the window at snowy Michigan probably had any Ford Motor Company engineer, researcher, or scientist thinking that developing and researching space systems, air cushioned vehicles, and computer components in sunny Newport Beach, California, was the way to go.

Aeronutronic Systems, Inc. was formed as a subsidiary of Ford in 1956 under the leadership of G.J. Lynch. The group was originally organized to develop and manufacture products for military purposes in the fields of Complete Weapons Systems, Aeronautics, Electronics, Computers, and Nucleonics and Physics. By 1959, the group was a made a division of Ford and had expanded into research and development beyond military purposes.

Lobby, computer products building. / THF627413

The division was headquartered in Newport Beach, California. Brochures for the division flaunted its cutting-edge research facilities, testing laboratories, research library, and proximity to deep-sea fishing, sailing, skiing, and the fact that the temperature rarely dropped below 44 or rose above 75.

Aeronutronic campus map. / THF627410

The groups within the division worked on a variety of projects. The Space Systems group completed projects including the Blue Scout vehicle, which tested equipment in space; a lunar capsule, designed to land on the moon with scientific testing equipment to gather data on the lunar environment; and a design for a space station.

Group of women who worked on the Blue Scout project. / THF627401

Artist's rendering of lunar capsule built by Ford Motor Company Aeronutronic Division, 1960. / THF141214

Space station concept drawing. / THF627416

In Weapons Systems, they worked on several missile projects, including the Shillelagh Guided Missile for the Army Missile Command, and ARTOC (Army Tactical Operations Central), which was a mobile command post for the Army Signal Corp.

ARTOC command board. / THF627406, detail

The Electronics and Computers division worked on BIAX computer components, as well as MIND (Magnetic Integration Neuron Duplication), an electronic neuron that duplicated the function of live nerve cells, among other things.

Computer elements. / THF627414

Research projects included surface tension tests; developing thin films solid state components; manufacturing the FLIDEN Flight Data Entry Unit, which was used as part of the FAA air traffic control system; and developing an air cushioned vehicle.

FLIDEN unit, demonstrated by Ellen Arthur. / THF627397

Air-cushioned vehicle concept. / THF627420

The employees at the Aeronutronic division had fun too, with an employee newsletter to keep them up to date on company happenings as well as their many recreation leagues, which included bowling, basketball, and baseball among other sports, as well as chess and bridge clubs.

Fred Ju, team captain, bowling in the Men’s Bowling League. / THF627399

Members of the Bridge Club / THF627395

Aeronutronic continued to change with the times. In 1962, it became a division of the Ford subsidiary Philco, and in 1976 became Ford Aerospace and Communication Corporation, before being sold by Ford in 1990.

Kathy Makas is Reference Archivist at The Henry Ford. This post is based on a December 2021 presentation of History Outside the Box on The Henry Ford’s Instagram channel. Follow us there for new presentations on the first Friday of each month.

1960s, California, 20th century, 1950s, technology, space, History Outside the Box, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, computers, by Kathy Makas, archives

1964 Lincoln Continental Stretch Limousine

THF172232

THF172232

Fit for the pope, perfect for a parade!

Ford Motor Company was approached by the Vatican in 1965 to provide a vehicle in which to transport Pope Paul VI during a visit to New York City that October. It was an unprecedented occasion—no sitting pope had ever visited the United States before—and Ford was determined to meet the challenge. The automaker approached George Lehmann and Bob Peterson of Chicago. The two men had specialized in “stretching” and customizing Lincoln Continentals since 1962, and their firm had earned a reputation for the high quality of its work. Lehmann-Peterson did not disappoint, rushing a special car to completion in fewer than two weeks.

The papal Lincoln was lengthened to 21 feet (from the standard 18). Step plates and handrails were added for security personnel. Additional seats, arranged in a vis-à-vis (i.e., face-to-face) layout, were placed in the rear compartment. Supplemental interior lighting and a public address system allowed the pontiff to be seen and heard by the crowds, and an adjustable seat—capable of being raised several inches—further improved his visibility. A removable roof panel and added windscreen allowed the pope to stand and wave when conditions permitted.

Pope Paul VI Pictured Visiting New York in 1965 / THF128756

Pope Paul VI spent a whirlwind 14 hours touring New York on October 4, 1965. He gave a blessing at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, met with President Lyndon Johnson at the Waldorf Astoria hotel, addressed the UN General Assembly, and led an outdoor mass at Yankee Stadium. The pontiff ended his tour with a visit to the Vatican exhibit at the New York World’s Fair.

The modified Lincoln returned to Chicago where it served as a city parade car for visiting dignitaries. In 1968, the Vatican called once again, this time requesting the car’s use during a papal visit to Bogotá, Colombia. The car again performed flawlessly, despite Bogotá’s high altitude and the engine modifications made to the vehicle as a result.

Apollo 13 Astronauts Jack Swigert and Jim Lovell in a Parade, Chicago, Illinois, May 1, 1970 / THF288386

The car went back to Chicago and soon carried a new series of dignitaries. Apollo 8 astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and William Anders—the first men to orbit the Moon—were paraded in the car on a visit to the Windy City in January 1969. Seven months later, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins enjoyed a similar honor. The crews of Apollo 13 and Apollo 15 would later have their own parades in the Lincoln.

Continue Reading

Illinois, New York, 20th century, 1960s, space, popular culture, limousines, Ford Motor Company, convertibles, cars, by Matt Anderson

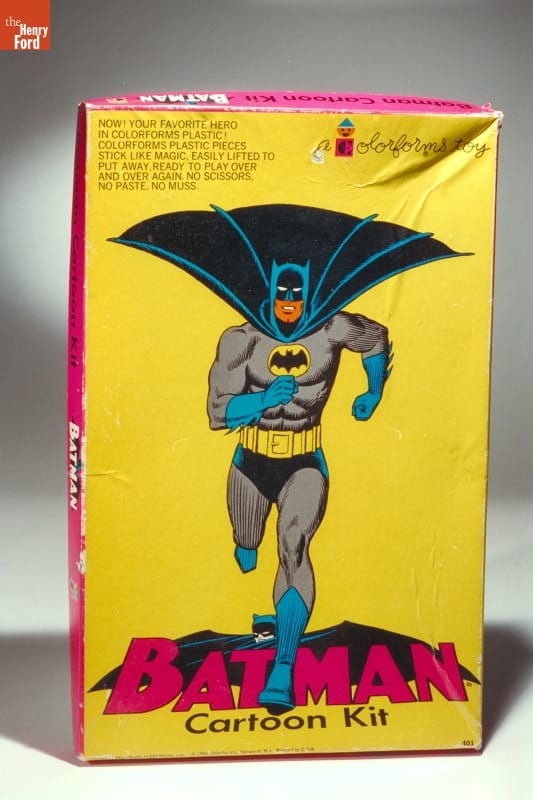

“Batman Cartoon Kit” Colorforms, 1966-68. THF 6651

It was the 1960s—the golden age of television. Some 95% of American homes boasted at least one TV. These were primarily black and white sets, as color TV was still out of the reach of many families. It’s hard to imagine now but there were only three channels at the time. Every year, the three networks (CBS, NBC, and ABC) vied for viewer ratings, shifting and changing shows and showtimes at two pivotal times during the television season—Fall and Winter.

As the Fall 1966 season unfolded, it became evident to TV viewers that something extraordinary was happening. Sure, there were the usual long-running sitcoms, like Green Acres, Petticoat Junction, and The Beverly Hillbillies. But change was in the wind. A new crop of programs emerged—colorful, fast-paced, poking fun at things that were supposed to be serious and exploring contemporary social issues.

Why the difference all of a sudden? Many of these shows were aimed at the youth audience, considered by this time an influential group of TV watchers. Others purposefully took advantage of the new color televisions. Sometimes show producers and creators were simply tired of the old formulas and wanted to break out of the box.

Let’s take a look at a few highlights from the 1966-67 TV season—starting with the staid and true and working up to the wild and wacky—and see what all the hubbub was about!

Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color (Sunday, 7:30-8:30 p.m., NBC)

Snow Globe, “The Wonderful World of Disney,” 1969-79. THF174650

On Sunday nights since 1954, millions of Americans had tuned in to watch Walt Disney host his TV show, with a changing array of animated and live-action features, nature specials, movie reruns, travelogues, programs about science and outer space, and—best of all—updates on Walt Disney’s theme park, Disneyland. Since 1961, this show had been broadcast in color.

The 1966-67 season was particularly memorable because Walt Disney tragically passed away on December 15, 1966. But since the episodes had been pre-recorded, there was Walt still hosting them until April 1967. Viewers found this both comforting and disconcerting. Finally, after April, Walt was dropped as the host and, eventually, the show was retitled The Wonderful World of Disney. It ran with solid ratings until the mid-1970s.

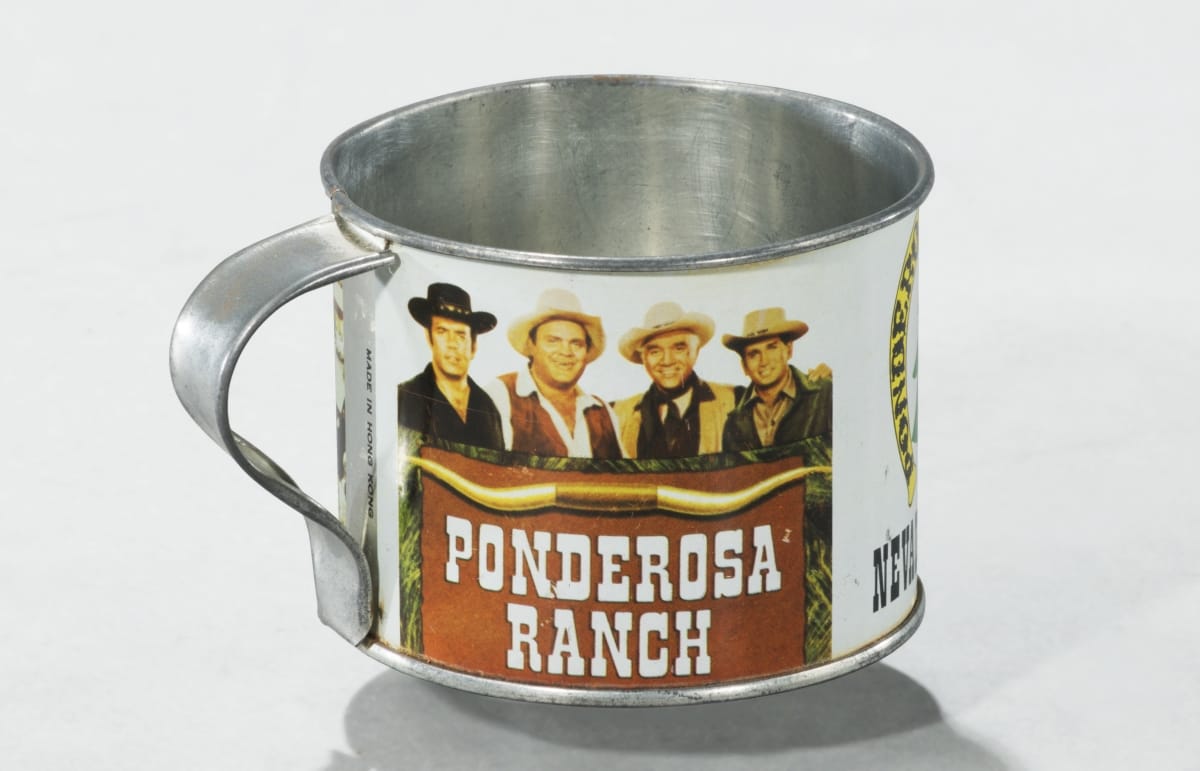

Bonanza (Sunday, 9:00-10:00 p.m., NBC)

“Ponderosa Ranch” Mug, ca. 1970. THF174648

Viewership was high on NBC on Sunday nights at 9:00, as Bonanza was one of the most popular TV shows of all time. Running for 14 seasons and 430 episodes, this series about the trials and tribulations of widower Ben Cartwright and his three sons on the Ponderosa Ranch was an immediate breakout hit when it premiered in 1959, amidst a plethora of more run-of-the-mill prime-time westerns. Its popularity was primarily due to its quirky characters and unconventional stories—including early attempts to confront social issues. It was the first major western to be filmed in color and was the top-rated show on TV from 1964 to 1968. Bonanza ran until 1973.

The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (Friday, 8:30-9:30, NBC)

“The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” lunchbox and thermos, 1966. THF92303

Premiering in September 1964, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. took full advantage of the popularity of the spy genre launched by the James Bond film series. In fact, early concepts for it were conceptualized by Bond creator Ian Fleming. In this series, Napoleon Solo (originally conceived as the lone star) and Russian agent Ilya Kuryakin (added in response to popular demand) teamed up as part of a secret international counterespionage and law enforcement agency called U.N.C.L.E. (United Network Command for Law and Enforcement). Solo and Kuryakin banded together with a global organization of other agents to fight THRUSH, an international organization that aimed to conquer the world.

During this, the Cold War era, it was groundbreaking for a show to portray a United States-Soviet Union pair of secret agents, as these two countries were ideologically at odds most of the time. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was also known for its high-profile guest stars and—taking a cue from the Bond films—its clever gadgets. In 1966, this series won the Golden Globe for Best Television Program and, building upon its popularity, spun off into two related double-feature movies that year. Unfortunately, attempting to compete with lighter, campier programs of the era, the producers made a conscious effort to increase the level of humor—leading to a severe ratings drop. Although the serious plot lines were soon reinstated, the ratings never recovered. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was canceled in January 1968.

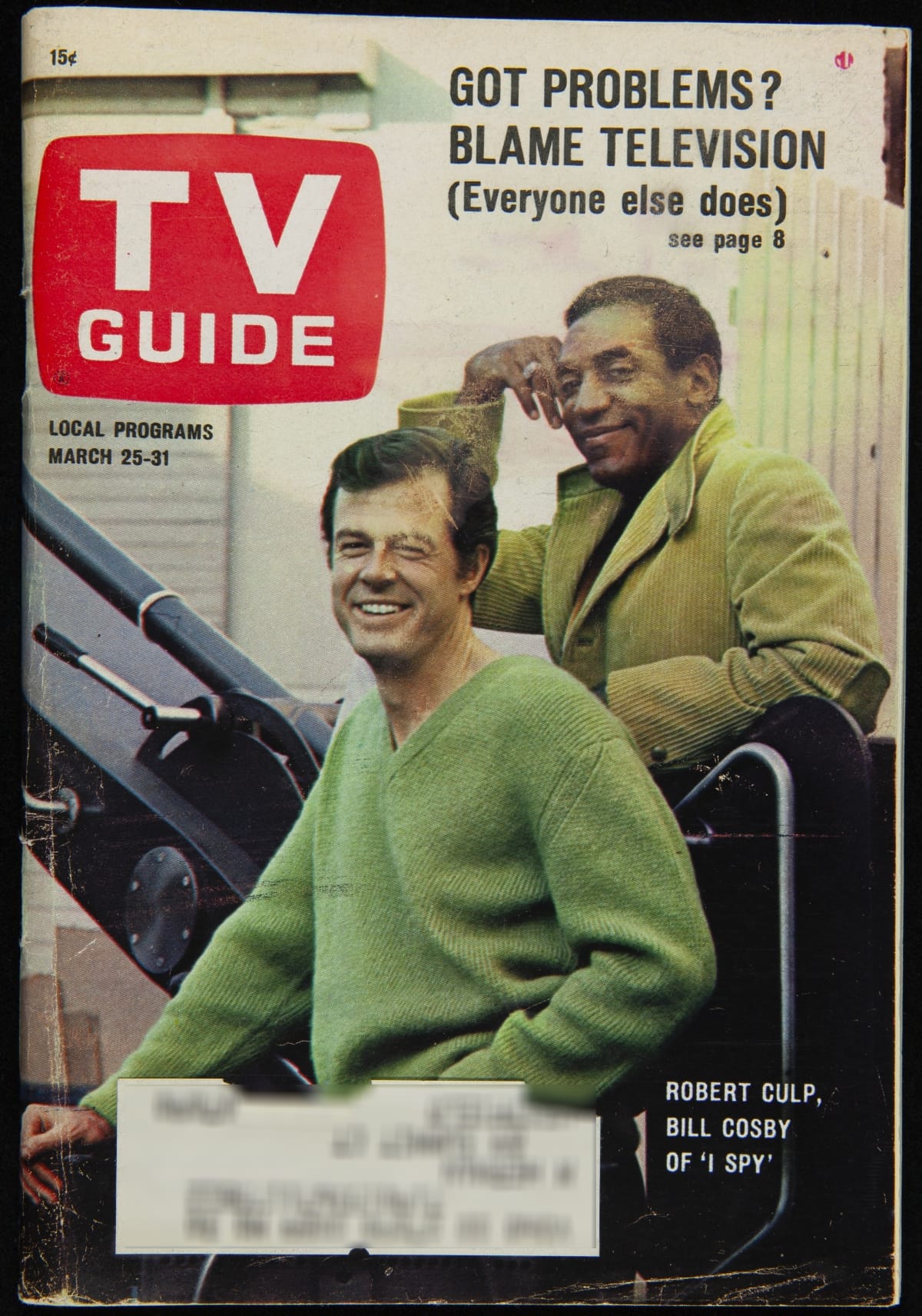

I Spy (Wednesday 10:00-11:00, NBC)

TV Guide featuring “I Spy” characters Robert Culp and Bill Cosby on cover, March 25-31, 1967. THF275655

One series that never opted for campy was I Spy, which starred Bill Cosby and Robert Culp playing two U.S. intelligence agents traveling undercover as international “tennis bums.” This series, which premiered in 1965, was also inspired by the James Bond film series and remained a fixture in the secret agent/espionage genre until cancelled in April 1968. I Spy, additionally a leader in the buddy genre, broke new ground as the first American TV drama series to feature a black actor in a lead role. It was also unusual in its use of exotic locations—much like the James Bond films—when shows like The Man from U.N.C.L.E. were completely filmed on a studio backlot.

I Spy offered hip banter between the two stars and some humor, but it focused primarily on the grittier side of the espionage business, sometimes even ending on a somber note. The success of this series was attributed to the strong chemistry between Culp and Cosby. Cosby’s presence was never called out in the way that black stars and co-stars were made a big deal of on later TV programs like Julia (1968) and Room 222 (1969).

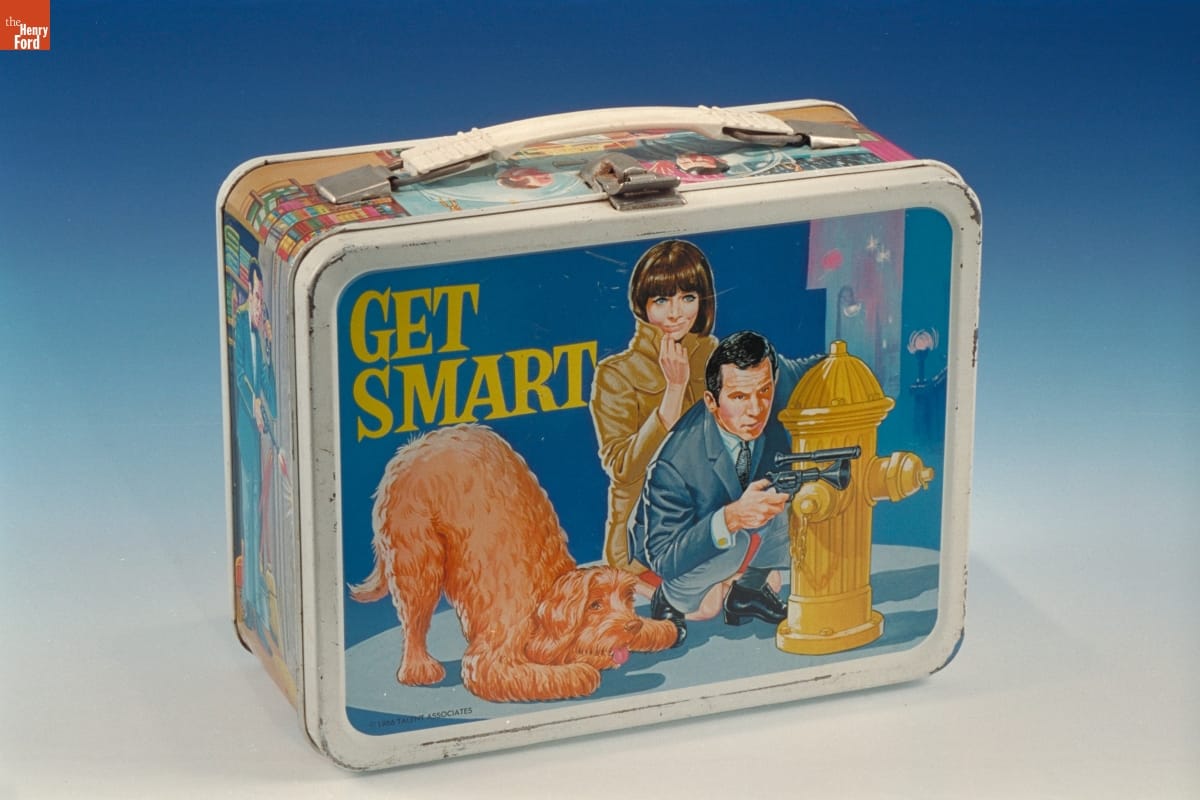

Get Smart (Saturday, 8:30-9:00 NBC)

“Get Smart” Lunchbox, 1966. THF92304

Premiering in September 1965, Get Smart was a comedy that satirized virtually everything considered serious and sacred in the James Bond films and such TV shows as I Spy and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Created by comic writers Mel Brooks and Buck Henry as a response to the grim seriousness of the Cold War spy genre, it starred bumbling Secret Agent 86—otherwise known as Maxwell “Max” Smart, along with supporting characters, female Agent 99 and the Chief. These characters worked for CONTROL, a secret U.S. government counterintelligence agency, against KAOS, “an international organization of evil.” Brooks and Henry also poked fun at this genre’s use of high-tech spy gadgets (Max’s shoe phone perhaps being the most memorable), world takeover plots, and enemy agents. Somehow, despite serious mess-ups in every episode, Maxwell Smart always emerged victorious in the end.

Get Smart was considered groundbreaking for broadening the parameters of TV sitcoms but was especially known for catchphrases like “Would you believe…” and “Sorry about that, Chief.” Despite a declining interest in the secret-agent genre, Get Smart’s talented writers attempted to keep it fresh until it was finally cancelled in May 1970.

Batman (Wednesday and Thursday, 7:30-8:00, ABC)

Toy Batmobile, 1966-69. THF174647

Bursting onto the scene in January 1966, Batman became an instant hit and took the country by storm. Batmania was in full swing by the Fall 1966-67 TV season. The series, based upon the DC comic book of the same name, featured the Caped Crusader (millionaire Bruce Wayne in his alter-ego of Batman) and the Boy Wonder (his young ward Dick Grayson in his alter-ego of Robin). These two crime-fighting heroes defended Gotham City from a variety of evil villains. It aired twice weekly, with most stories leaving viewers hanging in suspense the first night until they tuned in the second night.

This show successfully captured the youth audience, with its campy style, upbeat theme music, and tongue-in-cheek humor. Despite the fact that it verged on being a sitcom, the producers wisely left out the laugh track, reinforcing the seriousness with which the characters seemed to take the often absurd and wildly improbable situations in which they found themselves. The filming simulated a surreal comic-book quality, with characters and situations shot at high and low angles, with bright splashy colors and with sound effects, like Pow, Bam, and Zonk, appearing as words splashed across the action sequences on screen. The series was also replete with numerous gadgets and over-the-top props, with the Batmobile undoubtedly most memorable. Batman ran until March 1968, experiencing a significant ratings drop after its initial novelty faded.

Lost in Space (Wednesday 7:30-8:30, CBS)

“Lost in Space” Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967. THF92298

Loosely based upon the story of the Swiss Family Robinson, this TV series depicted the adventures of the Robinson family, a pioneering family of space colonists who struggled to survive in the depths of space in the futuristic year of 1997—as the United States was gearing up to colonize space due to overpopulation. But the family’s mission was sabotaged, forcing the crew members to crash-land on a strange planet and leaving them lost in space.

The show had premiered in September 1965 as a serious science fiction series about space exploration and a family searching to find a new place for humans to dwell. But, in January 1966, pitted against Batman’s time slot, Lost in Space producers attempted to imitate Batman’s campiness with ever-more-outrageous villains, brightly colored outfits, and over-the-top action. The plots increasingly featured Robby the Robot and the evil Dr. Zachary Smith. Viewers and actors alike strongly disapproved of this shift. The show lingered on until March 1968.

The Monkees (Monday, 7:30-8:00, NBC)

“Monkees” Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967. THF92313

Where other shows might have been lighthearted, campy, or tongue-in-cheek, The Monkees at times verged on pure anarchy. This series, which premiered on September 12, 1966, led off NBC’s prime-time programming every Monday night. It lasted only two seasons but during that time, its star shone brightly. The Monkees followed the experiences of four young men trying to make a name for themselves as a rock ‘n’ roll band, often finding themselves in strange, even bizarre, circumstances while searching for their big break. Aimed directly at the youth audience, the band members were characterized as heroes down on their luck while the adults were consistently depicted as the “heavies.”

The Beatles’ films A Hard Day’s Night and Help! inspired producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider to create not only a show about a rock ‘n’ roll band but also to adapt a loose narrative structure (each member of the Monkees was trained in improvisational acting techniques at the outset of the show) and the musical sequences or “romps” that appeared each week. The series built a reputation for its innovative use of avant-garde filming techniques like quick jump cuts and breaking the fourth wall (that is, having the characters directly address the TV viewers). A well-oiled marketing machine behind the show also ensured that strong tie-ins were maintained with teen magazines, merchandise, and live concerts.

The Monkees won the Emmy for best comedy series during its first, the 1966-67, season. However, backlash was inevitable among critics and older teenagers when the Monkees admitted that they did not play their own instruments—although they clearly played them in their live concerts and, in fact, eventually had a falling-out with network executives about this very issue. Though the show was cancelled in 1968, it experienced a huge revival among younger audiences through Saturday morning reruns and especially with the 1986 MTV Monkees Marathon. Remaining band members Micky Dolenz and Mike Nesmith still attract large audiences of intergenerational fans at their live concerts, while reruns of their TV shows continue to draw new audiences.

Star Trek (Thursday, 8:30-9:30 NBC)

“Star Trek” lunchbox, 1968. THF92299

When Star Trek premiered on September 8, 1966, science fiction shows were not very advanced—or even thought of very highly. Star Trek’s closest competitor, Lost in Space, offered only shallow plots, one-dimensional characters, and fake sets. No one could imagine at the time that this rather low-key show would become one of the biggest, longest-running, and highest-grossing media franchises of all time. This series traced the interstellar adventures of Captain James T. Kirk and his crew aboard the United Federation of Planets’ starship Enterprise, on a five-year mission “to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before.”

Creator Gene Roddenberry, aiming the show at the youth audience, wanted to combine suspenseful adventure stories with morality tales reflecting contemporary life and social issues. So, to get by network scrutiny, he set the premise of the show in an imaginary future. With the freedom to experiment, he put in place one of TV’s first multiracial and multicultural casts and was able to explore through different episodes some of the most relevant political and social allegories on TV at the time. The stories were also considered exceptionally high quality for that era, involving believable characters with which viewers could both identify and sympathize. Unlike the gloomy predictions of most science fiction writings of the time, Roddenberry hoped that the futuristic utopia he created on Star Trek would give young people hope, that it would empower them to create a better future for themselves someday. Star Trek, with only modest ratings, lasted only three seasons. But it would go on to become a cult classic.

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (Sunday, 9:00-10:00 p.m. beginning February 1967, CBS)

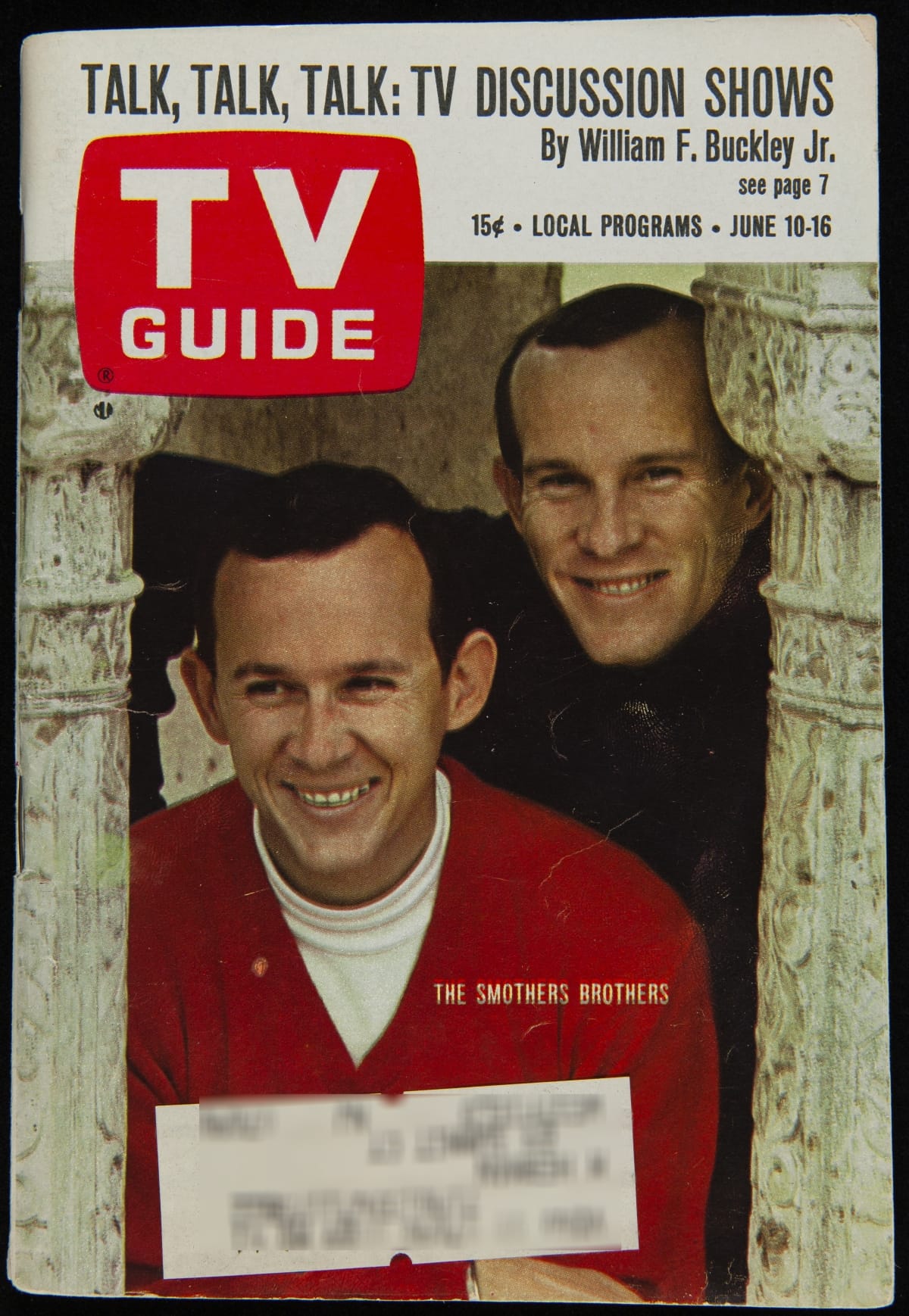

TV Guide featuring The Smothers Brothers on cover, June 10-16, 1967. THF275657

In Fall 1966, The Garry Moore Show, a variety show on CBS hosted by the aging radio and TV star, was no match when pitted against Bonanza—even with this, its first season in color. Network executives, at their wit’s end to try to attract viewership, decided the only way they could come up with a quick replacement was to substitute another variety show. In desperation, they landed on a simple variety series featuring the soft-spoken, clean-cut, non-threatening folk-music-playing Smothers Brothers. Considered a “young act,” an added bonus was that their show might capture the coveted youth audience. Little did they know what they were in for.

As the show evolved, the brothers not only became more politicized themselves but felt that they owed it to their young viewers to increase the show’s relevance, boldly addressing overtly divisive political and social issues. Their staff of young writers was only too happy to comply. Unfortunately, as a result, the brothers were continually at odds with the network censors until the show was finally cancelled after three seasons. In its continual conflicts with network executives, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour turned the variety show genre on its ear and paved the way for Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1968) and, in pushing TV’s all-out rebellion against the status quo, led an explosive charge that resulted in 1970s shows like All in the Family (1971).

These are but a few highlights from the 1966-67 TV season. Some say that this was the greatest television season ever, a clear indication that TV had finally come of age. Because of shows like these, television would certainly never be the same again. And, come to think of it, neither would we!

Donna Braden, Curator of Public Life, was 13 years old during that memorable TV season and proudly wears her fan club button to every Monkees concert she still attends.

20th century, 1960s, TV, Star Trek, space, popular culture, music, Disney, by Donna R. Braden

Symbols of the Space Age

Kitschy coin collectors convey Americans’ changing views of man’s ability to go where none had gone before.

There was a time when outer space belonged to the realm of fantasy and science fiction. Through movies, radio, television, comic strips and comic books, kids cheered as fantasy space heroes like Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers and Tom Corbett--Space Cadet safeguarded Earth’s inhabitants from evil forces. Futuristic space toys proliferated, from atomic ray guns and wind-up robots to toy spaceships. Then something happened. The United States and the Soviet Union began to explore outer space for real. When the Russians launched Sputnik I in October 1957, the “space race” took off, leading to a new era of more realistic space toys.

The Henry Ford’s collection of space-themed banks, dating from 1949 to 1964, captures the span of these two perceptions of outer space — as just a fantasy world to being a real place into which humans ventured. These mechanical banks, produced by Detroit-based companies Duro Mold & Manufacturing and Astro Manufacturing, were offered at individual bank branches as incentives for kids to start bank accounts. Having the branch bank’s name affixed to the front of one of these futuristic coin collectors was a sure sign that the financial institution was modern, progressive and in step with the times.

Atomic bank (c. 1949): co-opting a popular word of the Cold War era.

Rocket bank (c. 1951): resembling comic-book-style rockets.

Strato bank (c. 1953): the coin was shot through the “stratosphere” to the moon.

Guided missile bank (c. 1957): the first type made by Astro.

Plan-It bank (c. 1959): a play on words, depicting the sun surrounded by nine orbiting planets.

Satellite bank (c. 1961): this time - resembling a real rocket.

Unisphere bank (c. 1964): topped by the iconic centerpiece from the New York World’s Fair.

Destination moon bank (c. 1962): featuring the moon atop a realistic-looking rocket.

See more mechanical banks in our digital collections.

Donna Braden is Senior Curator & Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

One Giant Leap for Mankind

Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon Landing

The Space Race began in the 1950s, when both the United States and the Soviet Union attempted to launch ballistic missiles into outer space. Americans were surprised when the Russians beat them to it, launching the Sputnik I satellite in October 1957. But, when Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin orbited earth on April 12, 1961, Americans were downright shocked and not a little concerned. As a response, President Kennedy pledged to support a more aggressive space program than President Eisenhower had initiated before him.

On May 25, 1961, President Kennedy laid out a bold vision—that America should commit itself to landing a man on the moon “before the decade is out.” When astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin A. “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr. finally did set foot on the moon on July 20, 1969, many people considered it America’s finest hour.

Learn more about these artifacts below and then see them for yourself in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation during our pop-up exhibit now on display this summer.

This pictorial souvenir card depicts President Kennedy awarding NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal to America’s first astronaut, Navy Commander Alan B. Shepard, Jr., on May 8, 1961, three days after his successful flight.

Souvenir Card, 1961. THF230121

Trading cards like these generated excitement among America’s youth about the achievements of the space program.

Topps Astronaut Trading Cards, 1963. THF230119

This “Destination Moon” mechanical bank commemorates astronaut John Glenn’s achievement of orbiting the earth in 1962.

Mechanical Bank, 1962. THF173785. (Gift of Raymond Reines, Dedicated to the Berzac Family)

Congress had to approve a massive budget increase for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to make Kennedy’s bold vision even a remote possibility.

Recruiting Advertisement for NASA, July 1962. THF230079

NASA’s Apollo 11 lunar mission captivated audiences watching the drama unfolding on television. Some even documented the events with their personal cameras.

Photographic Print, July 20, 1969. THF114240

Print made from slide, July 20, 1969. THF114242

Four months before real men landed on the moon, Snoopy appeared in a Peanuts comic strip as the “World Famous Astronaut” walking on the moon. This Peanuts Pocket Doll commemorates the 1969 moon landing.

Snoopy Toy, 1969. THF52. (Gift of CarolAnn Missant)

This coloring book included the Mercury, Apollo, and Saturn vehicles and astronauts, as well as some history of the space program.

Coloring Book, 1969. THF292641

Those who viewed the moon landing on TV on July 20, 1969, often have difficulty separating the historic occasion from the steadfast reporting of it by Cronkite—considered at the time “the most trusted man in America.”

Record Album, Narrated by Walter Cronkite, 1969. THF110908

The cover story for this issue contained an in-depth report of the historic moon-landing mission.

Time Magazine for July 25, 1969. THF230050. (Gift of the Estate of Dr. and Mrs. Martin A. Glynn)

This commemorative game, simulating the successful moon landing, had players collecting “moon rocks.”

Board Game, 1969-1975. THF91918

This phonograph record comprises a “recorded history of space exploration and the triumph of the lunar landing.”

Record Album, 1969. THF154908. (Gift of the Estate of Dr. and Mrs. Martin A. Glynn)

At the height of the Apollo space program, Marathon Gas Stations offered a series of promotional glasses featuring the Apollo 11, 12, 13, and 14 missions.

Tumblers commemorating Apollo 11 mission, circa 1969. THF175132 (Gift of Jan Hiatt)

The Apollo 11 astronauts took pieces of the 1903 Wright Flyer—the first practical heavier-than-air flying machine—on their 1969 mission to symbolize the incredible progress made in those 66 years. Here, Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong poses in front of the Wright brothers' home in Greenfield Village during a 1979 visit to The Henry Ford.

Photograph of Neil Armstrong in Greenfield Village, August 16, 1979. THF128246

The iconic image on this poster depicts Buzz Aldrin walking on the moon’s surface, a photo taken by Neil Armstrong.

Poster, 1969. THF56899

Read more

John Glenn, Space Hero

John F. Kennedy's Enduring Legacy

Donna Braden is Senior Curator & Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 2010s, 20th century, 1960s, space, by Donna R. Braden