Posts Tagged tv

Sesame Street 50th Anniversary

Big and Little Bird reinforce the concept of contrasting sizes in this 1973 Playskool puzzle. THF97463

No television show has influenced how we think about children’s learning and thought processes as much as Sesame Street. For 50 years, this innovative TV show has continually broken barriers in its portrayal of diverse human interactions and relationships, its clever integration of Jim Henson’s wildly creative Muppets, and its rapid-fire approach to teaching basic educational concepts.

The idea for Sesame Street began back in 1966 at a dinner party hosted by Joan Ganz Cooney, a TV publicist turned documentary producer, and her husband Tim. In attendance was Lloyd Morrisett, who was both Vice President of the philanthropic Carnegie Corporation and an experimental psychologist interested in children’s education. At the dinner, Morrisett described his three-year-old daughter’s fascination with television—which included not only tuning in to Saturday morning cartoons, but also watching the pre-programming test patterns on the screen and reciting every commercial jingle by heart. Talk turned to the potential of television as a medium for educating young children. Could the seemingly addictive quality of TV be harnessed to both entertain and instruct?

This monster with the insatiable appetite—especially for cookies—has, under adult pressure, increasingly shown an awareness for healthy eating habits. THF97460

Cooney quickly developed a proposal entitled, “The Potential Use of Television in Preschool Education.” Her goal was groundbreaking at the time—to test the premise that TV could help level the playing field in education, preparing less advantaged three- to five-year-olds for school by teaching basic academic skills, self-esteem, and positive socialization. In March 1968, Cooney and Morrisett announced the formation of the Children’s Television Workshop (CTW) and set out to create an educational TV show that would both appeal to young children and help them get a jump on learning. With an eight-million-dollar startup grant from private foundations and government agencies (including the rather skeptical Department of Education), Cooney was able to test ideas for the type of show she had in mind.

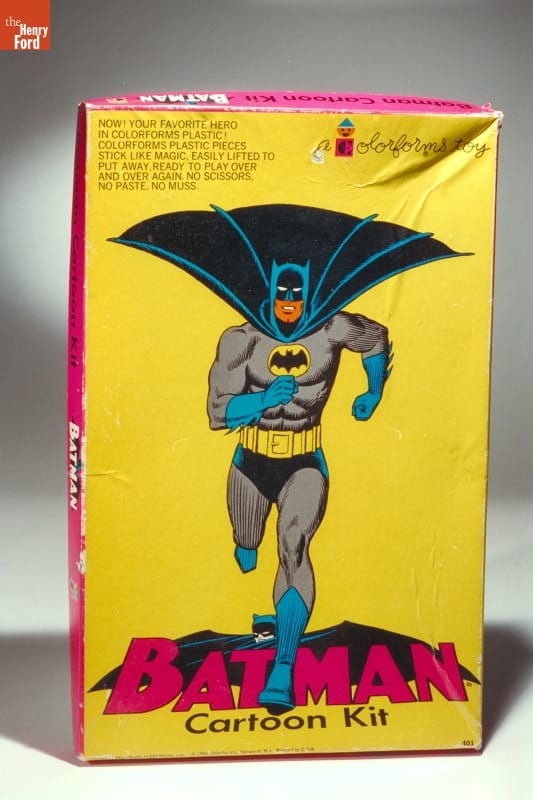

The colorful, fast-paced Batman TV show, which premiered in January 1966, provided one of many inspirations for Joan Ganz Cooney in creating Sesame Street. THF6651

Cooney’s reference points included the rapid-fire pacing of the hip new adult-oriented TV show, Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In. The campy breakout TV show Batman also provided a model, with its fast-paced action as well as its bright, bold colors and even its use of cartoon balloons. Cooney drew additional inspiration from short TV commercials, with their simple melodies in bright major keys. She did not get inspiration from most children’s TV shows, which she thought were dull, slow-paced, and seemed more oriented to adults than kids—with the possible exception of the kid-friendly Captain Kangaroo.

This 1970s Fisher-Price music box plays the song, “The People in Your Neighborhood,” while the Sesame Street scene moves horizontally across the “TV screen.” THF135804

Cooney soon realized that, while she had plenty of vision, she needed help in writing, directing, and producing the show. For this, she called on several veterans from Captain Kangaroo—most significantly Jon Stone, who played such a significant leadership role in shaping Sesame Street that he took over as executive producer for the next 20-odd years. Other talented and dedicated scriptwriters, composers, and directors also joined the team, while psychologists and educators lent their support from the beginning.

Cooney and her collaborators initially created a show that included brief skits, musical numbers, cartoons, and live-action video footage—all basically teaching school-readiness concepts. The idea of portraying a diverse group of people living and working together in a community was intentional, providing a hopeful real-life model for an integrated society, which encouraged respect, mutual tolerance, and cross-cultural friendship. The live action scenes were interspersed with pre-taped “commercials”—that is, short “bits” about letters and numbers presented either as animated segments or featuring Jim Henson’s Muppets. The live-action segments were purposely kept separate from the pre-taped “commercials,” as researchers felt that combining these “reality” and “fantasy” elements would confuse children.

Having the sweetly quizzical Big Bird live in a nest near, and interact with, the live actors on Sesame Street became a key to the show’s success. THF97451

Initial testing, however, revealed that children thought the live-action scenes were boring, the dialog tedious and lengthy. On the other hand, they found the short “commercials” to be catchy and memorable. Pushing back on the researchers’ advice, Cooney and Stone brought in Jim Henson as a full-time producer, while his Muppet creations Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch joined the live-action human cast. The resulting interaction between humans and Muppets—seamless and convincing—provided the missing alchemy. The foundation was laid for Sesame Street as we know it today.

Ongoing episodes about ultra-serious Bert and fun-loving Ernie reinforce to children that vastly different personalities can still be good friends. THF92308

The first episode of Sesame Street premiered on November 10, 1969 and the show aired weekdays on the new Public Broadcasting System (PBS) network. It was immediately hailed as a groundbreaking blend of learning and fun, despite some criticism about its high entertainment quotient, its threat to teachers for undermining early school lessons, and—in Mississippi—its initial banning because of its integrated cast. Time magazine featured popular Sesame Street character Big Bird on its November 23, 1970 cover, next to the headline, “Sesame Street: TV’s Gift to Children.” This issue devoted nine pages to the show’s impact and importance, calling it “the best children’s show in TV history.”

Puppeteer Kevin Clash breathed new energy and vitality into Elmo in the 1980s, but this furry red Muppet became a breakout star in 1996, when comedienne Rosie O’Donnell featured both Clash and this doll on her TV show. THF176791

As Sesame Street has continually changed and grown with the times, its popularity and impact have endured. Comedienne Rosie O’Donnell, whose remarks on her own TV show helped transform Elmo from a minor character to a superstar, described the show’s unique contributions this way:

"From the beginning Sesame Street encouraged imagination and playfulness. It always felt like a show to me about freedom, and it has always spoken to children in a pure and truthful way. Children are children, rich or poor, and there is a language of truth that is innate to these tiny, undeveloped beings that they can hear. Sesame Street had respect for its audience and respect for itself. They never cut any corners and they stuck to their democratic ideals."

Innovative, groundbreaking, and radical when it was introduced, Sesame Street has become nothing short of an American institution.

Donna Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

1960s, 20th century, 21st century, 2010s, TV, popular culture, Jim Henson, education, childhood, by Donna R. Braden

A Technological Assist

Assistive technology refers to a wide range of products designed to help people work around a variety of challenges as they learn, work, and perform other daily living activities. Certain assistive devices allow people who are deaf or hard of hearing to access technologies that many take for granted, like telephones, televisions, and even alarm clocks. For a young woman in the 1970s and 80s, these products -- now in the collections of The Henry Ford -- also provided greater independence, broader access to popular culture, and improved communication with family and friends.

Hal-Hen Products Vibrating Alarm Clock, circa 1975 (THF158135)

In September 1975, just before leaving home to begin college, a young woman named Shari acquired this inventive alarm clock. It included a bedside clock connected to a vibrating motor, which attached to the underside of the bed and shook intensely when the alarm was triggered. The eager freshman looked forward to waking independently, “rather than trying to rely on others who would have a different class schedule” -- so it’s easy to imagine her dismay when she arrived at her dormitory to find bunk beds! The alarm “would shake and rattle the whole bunk,” creating “quite a rude awakening” for her bunkmate. After a few nights, the students figured out how to separate their bunk beds into twin beds. Even though the new arrangement made the small dorm room even tighter, Shari (and, undoubtedly, her roommate) finally considered the alarm clock to have been “a definite advantage.”

Brochure, "Real-Time Closed Captioning Brings Early-Evening News to the Hearing Impaired, circa 1981 (THF275615)

In December 1981, with money saved from her first job after college, Shari purchased a television caption adapter. At this time, a few programs, like the national news, were broadcast with closed captions for viewers who were deaf or hard of hearing. This text was visible only when activated, at first through separate decoding units.

Television Caption Adapter, 1980-1981 (THF173767)

Shari remembered -- especially as more shows began to include closed captions in the 1980s -- that this decoder “opened up a whole new world of entertainment.” She associated closed captioning with independence -- as she didn’t “have to pester other family members to ‘tell me what they're saying’” -- and participation, recalling, “No longer did I resign myself to reading a book in an easy chair in the same room while the rest of the family watched exciting shows on TV!” The Television Decoder Circuitry Act of 1990 required televisions to have built-in caption display technology, decreasing the need for separate caption adapters and giving people access to on-screen captions almost anywhere they watched TV.

System 100 Text Telephone Unit, circa 1980 (THF173771)

In 1981, the same year she purchased her first TV caption adapter, Shari also acquired a teletypewriter, or text telephone, abbreviated TTY. This device connected to a standard telephone line, allowing communication via a keyboard and electronic text display. The technology was freeing -- Shari remembered that “it was wonderful to finally be able to independently make a few of my own phone calls” -- but also limited. At first, she could only communicate with someone else who had access to a TTY device. After she became a mother, Shari recalled loaning a TTY unit to a neighbor who also had small children, making it easier to “set up ‘play dates’ and just do the typical conversing young moms do.” In the late 1980s, some states implemented services to relay dialogue between TTY and non-TTY users. Eventually, spurred by state and federal legislation, relay systems improved nationwide, and TTY technology became more accessible and affordable.

In their time, these lifechanging devices represented the cutting edge of assistive technology. Ongoing research, technological ad vances, and new design approaches in the decades that followed led to improved products and more choices for consumers. Today, many users have adopted digital technologies. Email, text or instant message, and real-time video services enable communication, and digital devices, often connected to smartphones, offer solutions that address a range of user needs.

vances, and new design approaches in the decades that followed led to improved products and more choices for consumers. Today, many users have adopted digital technologies. Email, text or instant message, and real-time video services enable communication, and digital devices, often connected to smartphones, offer solutions that address a range of user needs.

Saige Jedele is Associate Curator, Digital Content, at The Henry Ford. Learn more about assistive technology on an upcoming episode of The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation.

home life, TV, clocks, communication, by Saige Jedele, technology, accessibility

“Batman Cartoon Kit” Colorforms, 1966-68. THF 6651

It was the 1960s—the golden age of television. Some 95% of American homes boasted at least one TV. These were primarily black and white sets, as color TV was still out of the reach of many families. It’s hard to imagine now but there were only three channels at the time. Every year, the three networks (CBS, NBC, and ABC) vied for viewer ratings, shifting and changing shows and showtimes at two pivotal times during the television season—Fall and Winter.

As the Fall 1966 season unfolded, it became evident to TV viewers that something extraordinary was happening. Sure, there were the usual long-running sitcoms, like Green Acres, Petticoat Junction, and The Beverly Hillbillies. But change was in the wind. A new crop of programs emerged—colorful, fast-paced, poking fun at things that were supposed to be serious and exploring contemporary social issues.

Why the difference all of a sudden? Many of these shows were aimed at the youth audience, considered by this time an influential group of TV watchers. Others purposefully took advantage of the new color televisions. Sometimes show producers and creators were simply tired of the old formulas and wanted to break out of the box.

Let’s take a look at a few highlights from the 1966-67 TV season—starting with the staid and true and working up to the wild and wacky—and see what all the hubbub was about!

Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color (Sunday, 7:30-8:30 p.m., NBC)

Snow Globe, “The Wonderful World of Disney,” 1969-79. THF174650

On Sunday nights since 1954, millions of Americans had tuned in to watch Walt Disney host his TV show, with a changing array of animated and live-action features, nature specials, movie reruns, travelogues, programs about science and outer space, and—best of all—updates on Walt Disney’s theme park, Disneyland. Since 1961, this show had been broadcast in color.

The 1966-67 season was particularly memorable because Walt Disney tragically passed away on December 15, 1966. But since the episodes had been pre-recorded, there was Walt still hosting them until April 1967. Viewers found this both comforting and disconcerting. Finally, after April, Walt was dropped as the host and, eventually, the show was retitled The Wonderful World of Disney. It ran with solid ratings until the mid-1970s.

Bonanza (Sunday, 9:00-10:00 p.m., NBC)

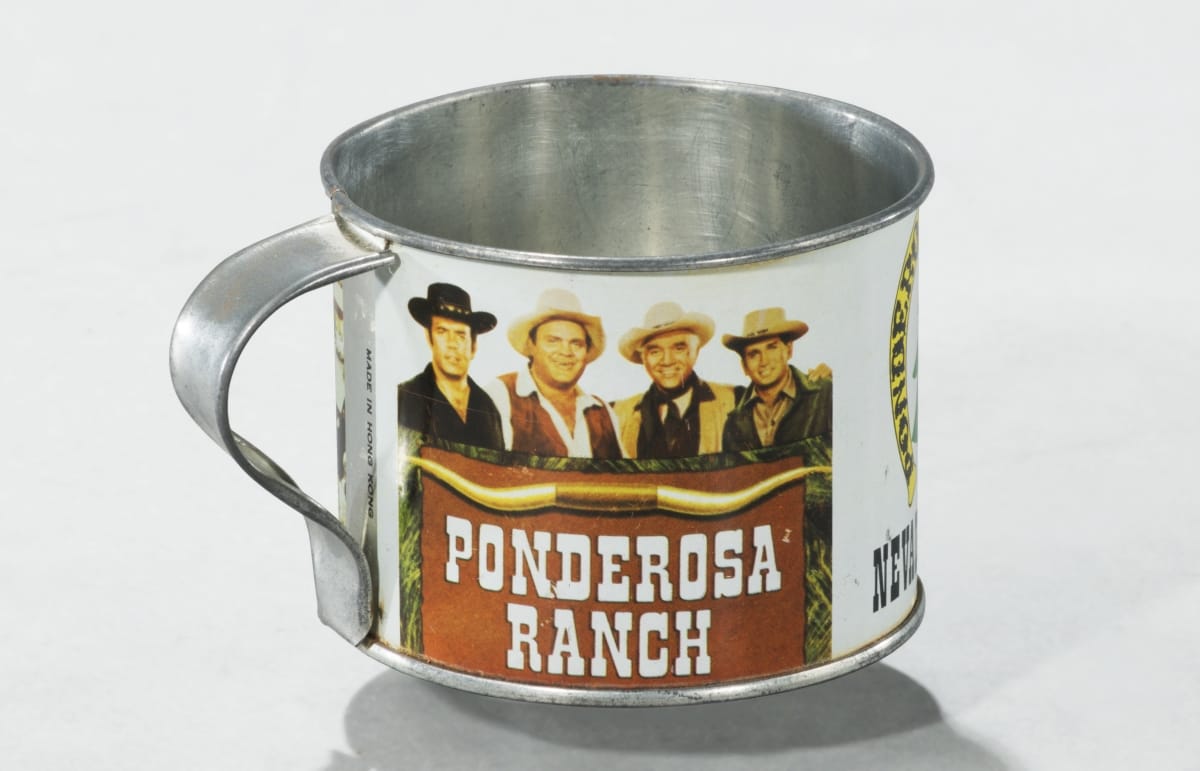

“Ponderosa Ranch” Mug, ca. 1970. THF174648

Viewership was high on NBC on Sunday nights at 9:00, as Bonanza was one of the most popular TV shows of all time. Running for 14 seasons and 430 episodes, this series about the trials and tribulations of widower Ben Cartwright and his three sons on the Ponderosa Ranch was an immediate breakout hit when it premiered in 1959, amidst a plethora of more run-of-the-mill prime-time westerns. Its popularity was primarily due to its quirky characters and unconventional stories—including early attempts to confront social issues. It was the first major western to be filmed in color and was the top-rated show on TV from 1964 to 1968. Bonanza ran until 1973.

The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (Friday, 8:30-9:30, NBC)

“The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” lunchbox and thermos, 1966. THF92303

Premiering in September 1964, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. took full advantage of the popularity of the spy genre launched by the James Bond film series. In fact, early concepts for it were conceptualized by Bond creator Ian Fleming. In this series, Napoleon Solo (originally conceived as the lone star) and Russian agent Ilya Kuryakin (added in response to popular demand) teamed up as part of a secret international counterespionage and law enforcement agency called U.N.C.L.E. (United Network Command for Law and Enforcement). Solo and Kuryakin banded together with a global organization of other agents to fight THRUSH, an international organization that aimed to conquer the world.

During this, the Cold War era, it was groundbreaking for a show to portray a United States-Soviet Union pair of secret agents, as these two countries were ideologically at odds most of the time. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was also known for its high-profile guest stars and—taking a cue from the Bond films—its clever gadgets. In 1966, this series won the Golden Globe for Best Television Program and, building upon its popularity, spun off into two related double-feature movies that year. Unfortunately, attempting to compete with lighter, campier programs of the era, the producers made a conscious effort to increase the level of humor—leading to a severe ratings drop. Although the serious plot lines were soon reinstated, the ratings never recovered. The Man from U.N.C.L.E. was canceled in January 1968.

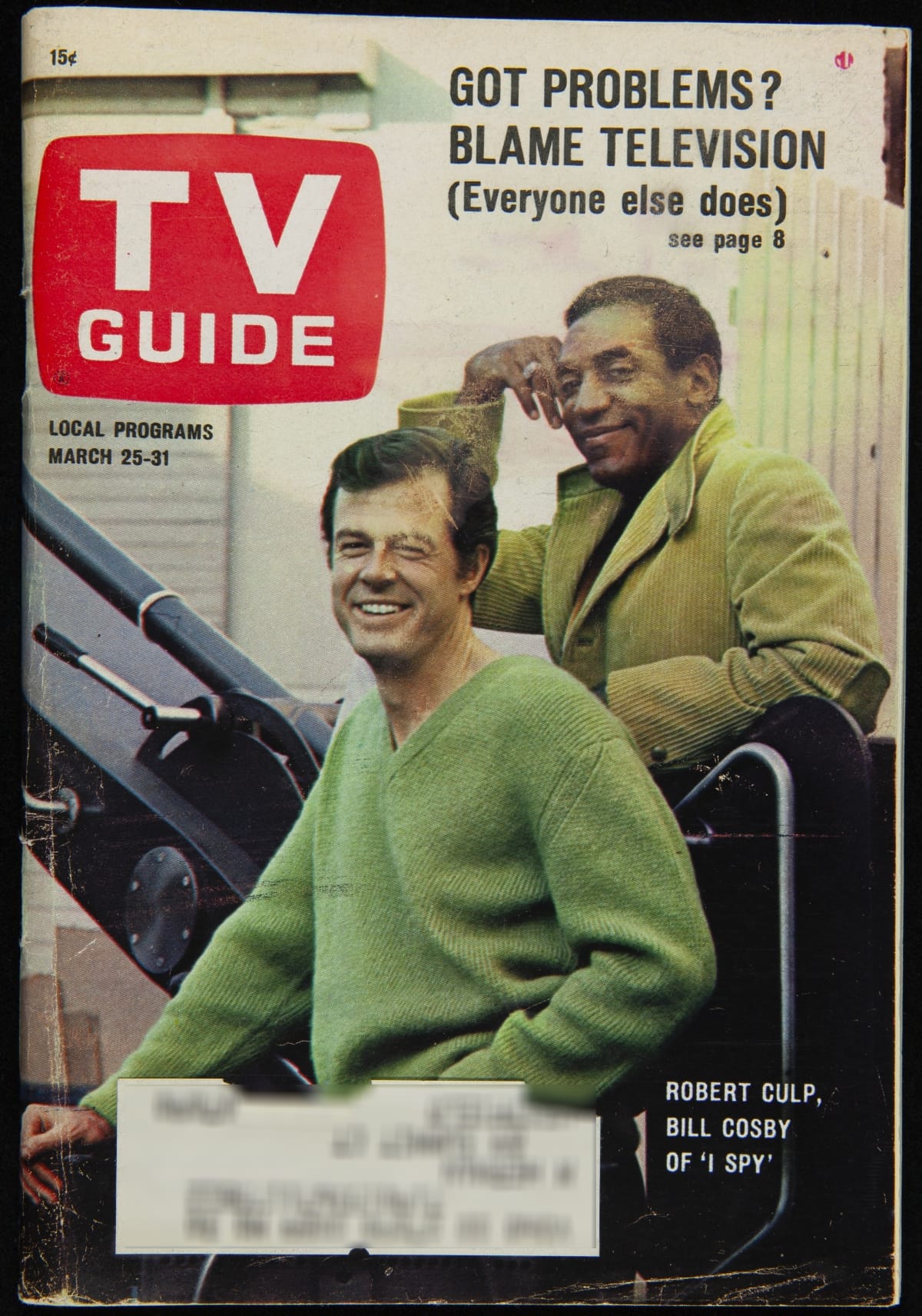

I Spy (Wednesday 10:00-11:00, NBC)

TV Guide featuring “I Spy” characters Robert Culp and Bill Cosby on cover, March 25-31, 1967. THF275655

One series that never opted for campy was I Spy, which starred Bill Cosby and Robert Culp playing two U.S. intelligence agents traveling undercover as international “tennis bums.” This series, which premiered in 1965, was also inspired by the James Bond film series and remained a fixture in the secret agent/espionage genre until cancelled in April 1968. I Spy, additionally a leader in the buddy genre, broke new ground as the first American TV drama series to feature a black actor in a lead role. It was also unusual in its use of exotic locations—much like the James Bond films—when shows like The Man from U.N.C.L.E. were completely filmed on a studio backlot.

I Spy offered hip banter between the two stars and some humor, but it focused primarily on the grittier side of the espionage business, sometimes even ending on a somber note. The success of this series was attributed to the strong chemistry between Culp and Cosby. Cosby’s presence was never called out in the way that black stars and co-stars were made a big deal of on later TV programs like Julia (1968) and Room 222 (1969).

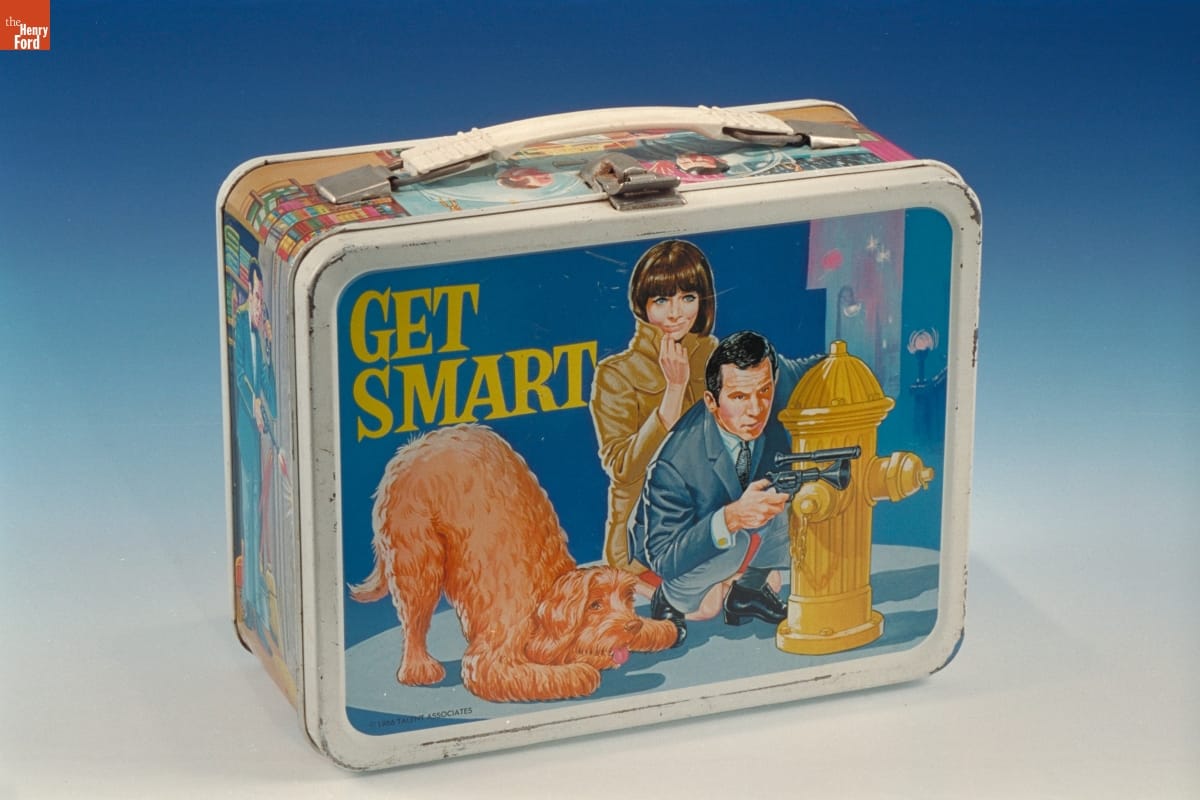

Get Smart (Saturday, 8:30-9:00 NBC)

“Get Smart” Lunchbox, 1966. THF92304

Premiering in September 1965, Get Smart was a comedy that satirized virtually everything considered serious and sacred in the James Bond films and such TV shows as I Spy and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Created by comic writers Mel Brooks and Buck Henry as a response to the grim seriousness of the Cold War spy genre, it starred bumbling Secret Agent 86—otherwise known as Maxwell “Max” Smart, along with supporting characters, female Agent 99 and the Chief. These characters worked for CONTROL, a secret U.S. government counterintelligence agency, against KAOS, “an international organization of evil.” Brooks and Henry also poked fun at this genre’s use of high-tech spy gadgets (Max’s shoe phone perhaps being the most memorable), world takeover plots, and enemy agents. Somehow, despite serious mess-ups in every episode, Maxwell Smart always emerged victorious in the end.

Get Smart was considered groundbreaking for broadening the parameters of TV sitcoms but was especially known for catchphrases like “Would you believe…” and “Sorry about that, Chief.” Despite a declining interest in the secret-agent genre, Get Smart’s talented writers attempted to keep it fresh until it was finally cancelled in May 1970.

Batman (Wednesday and Thursday, 7:30-8:00, ABC)

Toy Batmobile, 1966-69. THF174647

Bursting onto the scene in January 1966, Batman became an instant hit and took the country by storm. Batmania was in full swing by the Fall 1966-67 TV season. The series, based upon the DC comic book of the same name, featured the Caped Crusader (millionaire Bruce Wayne in his alter-ego of Batman) and the Boy Wonder (his young ward Dick Grayson in his alter-ego of Robin). These two crime-fighting heroes defended Gotham City from a variety of evil villains. It aired twice weekly, with most stories leaving viewers hanging in suspense the first night until they tuned in the second night.

This show successfully captured the youth audience, with its campy style, upbeat theme music, and tongue-in-cheek humor. Despite the fact that it verged on being a sitcom, the producers wisely left out the laugh track, reinforcing the seriousness with which the characters seemed to take the often absurd and wildly improbable situations in which they found themselves. The filming simulated a surreal comic-book quality, with characters and situations shot at high and low angles, with bright splashy colors and with sound effects, like Pow, Bam, and Zonk, appearing as words splashed across the action sequences on screen. The series was also replete with numerous gadgets and over-the-top props, with the Batmobile undoubtedly most memorable. Batman ran until March 1968, experiencing a significant ratings drop after its initial novelty faded.

Lost in Space (Wednesday 7:30-8:30, CBS)

“Lost in Space” Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967. THF92298

Loosely based upon the story of the Swiss Family Robinson, this TV series depicted the adventures of the Robinson family, a pioneering family of space colonists who struggled to survive in the depths of space in the futuristic year of 1997—as the United States was gearing up to colonize space due to overpopulation. But the family’s mission was sabotaged, forcing the crew members to crash-land on a strange planet and leaving them lost in space.

The show had premiered in September 1965 as a serious science fiction series about space exploration and a family searching to find a new place for humans to dwell. But, in January 1966, pitted against Batman’s time slot, Lost in Space producers attempted to imitate Batman’s campiness with ever-more-outrageous villains, brightly colored outfits, and over-the-top action. The plots increasingly featured Robby the Robot and the evil Dr. Zachary Smith. Viewers and actors alike strongly disapproved of this shift. The show lingered on until March 1968.

The Monkees (Monday, 7:30-8:00, NBC)

“Monkees” Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967. THF92313

Where other shows might have been lighthearted, campy, or tongue-in-cheek, The Monkees at times verged on pure anarchy. This series, which premiered on September 12, 1966, led off NBC’s prime-time programming every Monday night. It lasted only two seasons but during that time, its star shone brightly. The Monkees followed the experiences of four young men trying to make a name for themselves as a rock ‘n’ roll band, often finding themselves in strange, even bizarre, circumstances while searching for their big break. Aimed directly at the youth audience, the band members were characterized as heroes down on their luck while the adults were consistently depicted as the “heavies.”

The Beatles’ films A Hard Day’s Night and Help! inspired producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider to create not only a show about a rock ‘n’ roll band but also to adapt a loose narrative structure (each member of the Monkees was trained in improvisational acting techniques at the outset of the show) and the musical sequences or “romps” that appeared each week. The series built a reputation for its innovative use of avant-garde filming techniques like quick jump cuts and breaking the fourth wall (that is, having the characters directly address the TV viewers). A well-oiled marketing machine behind the show also ensured that strong tie-ins were maintained with teen magazines, merchandise, and live concerts.

The Monkees won the Emmy for best comedy series during its first, the 1966-67, season. However, backlash was inevitable among critics and older teenagers when the Monkees admitted that they did not play their own instruments—although they clearly played them in their live concerts and, in fact, eventually had a falling-out with network executives about this very issue. Though the show was cancelled in 1968, it experienced a huge revival among younger audiences through Saturday morning reruns and especially with the 1986 MTV Monkees Marathon. Remaining band members Micky Dolenz and Mike Nesmith still attract large audiences of intergenerational fans at their live concerts, while reruns of their TV shows continue to draw new audiences.

Star Trek (Thursday, 8:30-9:30 NBC)

“Star Trek” lunchbox, 1968. THF92299

When Star Trek premiered on September 8, 1966, science fiction shows were not very advanced—or even thought of very highly. Star Trek’s closest competitor, Lost in Space, offered only shallow plots, one-dimensional characters, and fake sets. No one could imagine at the time that this rather low-key show would become one of the biggest, longest-running, and highest-grossing media franchises of all time. This series traced the interstellar adventures of Captain James T. Kirk and his crew aboard the United Federation of Planets’ starship Enterprise, on a five-year mission “to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before.”

Creator Gene Roddenberry, aiming the show at the youth audience, wanted to combine suspenseful adventure stories with morality tales reflecting contemporary life and social issues. So, to get by network scrutiny, he set the premise of the show in an imaginary future. With the freedom to experiment, he put in place one of TV’s first multiracial and multicultural casts and was able to explore through different episodes some of the most relevant political and social allegories on TV at the time. The stories were also considered exceptionally high quality for that era, involving believable characters with which viewers could both identify and sympathize. Unlike the gloomy predictions of most science fiction writings of the time, Roddenberry hoped that the futuristic utopia he created on Star Trek would give young people hope, that it would empower them to create a better future for themselves someday. Star Trek, with only modest ratings, lasted only three seasons. But it would go on to become a cult classic.

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (Sunday, 9:00-10:00 p.m. beginning February 1967, CBS)

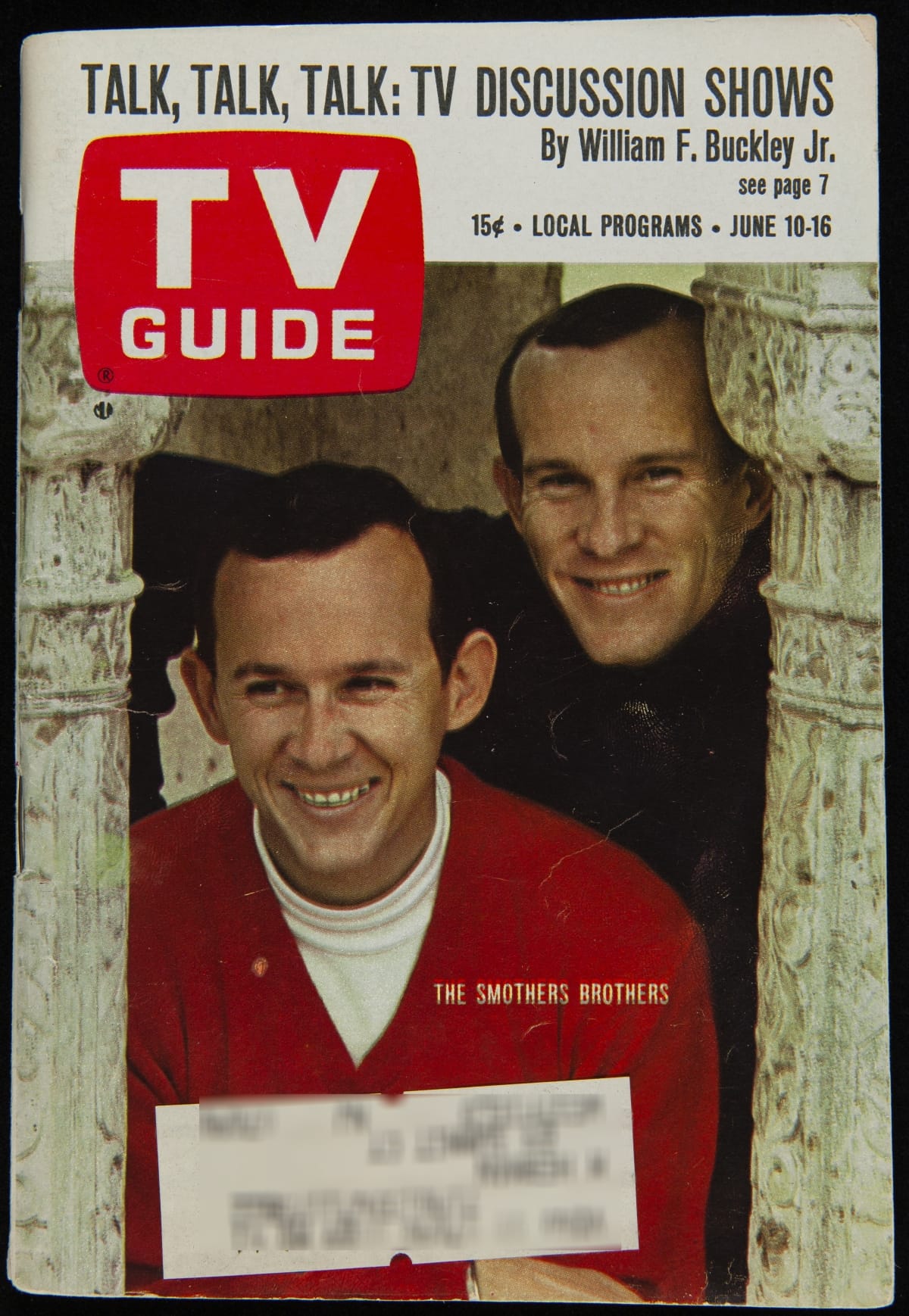

TV Guide featuring The Smothers Brothers on cover, June 10-16, 1967. THF275657

In Fall 1966, The Garry Moore Show, a variety show on CBS hosted by the aging radio and TV star, was no match when pitted against Bonanza—even with this, its first season in color. Network executives, at their wit’s end to try to attract viewership, decided the only way they could come up with a quick replacement was to substitute another variety show. In desperation, they landed on a simple variety series featuring the soft-spoken, clean-cut, non-threatening folk-music-playing Smothers Brothers. Considered a “young act,” an added bonus was that their show might capture the coveted youth audience. Little did they know what they were in for.

As the show evolved, the brothers not only became more politicized themselves but felt that they owed it to their young viewers to increase the show’s relevance, boldly addressing overtly divisive political and social issues. Their staff of young writers was only too happy to comply. Unfortunately, as a result, the brothers were continually at odds with the network censors until the show was finally cancelled after three seasons. In its continual conflicts with network executives, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour turned the variety show genre on its ear and paved the way for Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1968) and, in pushing TV’s all-out rebellion against the status quo, led an explosive charge that resulted in 1970s shows like All in the Family (1971).

These are but a few highlights from the 1966-67 TV season. Some say that this was the greatest television season ever, a clear indication that TV had finally come of age. Because of shows like these, television would certainly never be the same again. And, come to think of it, neither would we!

Donna Braden, Curator of Public Life, was 13 years old during that memorable TV season and proudly wears her fan club button to every Monkees concert she still attends.

20th century, 1960s, TV, Star Trek, space, popular culture, music, Disney, by Donna R. Braden

Is That from Star Trek?

We recently got together a number of our curators and staff, who are Star Trek fans and frequent visitors to our current exhibit "Star Trek: Exploring New Worlds," to brainstorm the many connections we might make between the collections of The Henry Ford and the media empire that is Star Trek. During that discussion, someone threw out an example of a name shared across both—but as we dug deeper, we also discovered the artifact had an interesting parallel to (or contrast with) the ship or character. Locating more of these seemed a fitting tribute to Star Trek’s characteristic combination of humor and seriousness.

Below are some similar examples we came up with. What other artifacts can you think of from our collection that share a name with—and perhaps a philosophical tie to—Star Trek?

1984 Plymouth Voyager Minivan

Chrysler boldly went where no carmaker had gone before when it introduced the minivan for 1984. With taller interiors and flatter floors (front-wheel drive eliminated that pesky driveshaft tunnel), minivans generally had more interior room than station wagons, and soon supplanted them as the ideal family car. And, at around 20 miles per gallon, the Plymouth Voyager probably got better fuel mileage than the U.S.S. Voyager of the eponymous series! –Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

Gondola Landing after Piccard Stratosphere Balloon Flight, Cadiz, Ohio, October 23, 1934

Four hundred thirty years before Captain Jean-Luc Picard would command the U.S.S. Enterprise, Jean and Jeannette Piccard engaged the stratosphere in a metal gondola attached to a hydrogen balloon. –Jim Orr, Image Services Specialist

Vulcan Brand Appliances Advertisement, 1905, "Vulcan- Handy Things for Every Home"

Star Trek’s half-Vulcan, half-human science officer, Spock, represented the polar opposite of the Roman god of fire, Vulcan. While the Roman god served as a harbinger of volcanic destruction, Spock modeled cool composure. In 1905, Vulcan Brand Appliances embraced the Roman mythology and marketed their toasters and curling-iron heaters as handy things for every home. What would Spock think? –Debra Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

Google Nexus Q, 2012

It didn’t sweep you into an extra-dimensional fantasy realm like the Nexus that trapped Kirk and Picard in Star Trek Generations, nor did it use omnipotent powers to tease your crew like the meddlesome Q of Star Trek: The Next Generation, but the Google Nexus Q could keep you entertained for hours on end with music, movies, and TV shows. –Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

Scot Towels, circa 1937

Montgomery Scott, known as "Scotty," is the Chief Engineer aboard the U.S.S. Enterprise in the original Star Trek series. The heavy Scottish accent adopted for the role by Canadian actor James Doohan became one of Scotty's hallmarks, as did his intense pride in the Enterprise, his sense of humor, his complaints when the ship encounters yet another tight spot, and the way he always tells Captain Kirk repairs will take longer than they actually will. Still, like this roll of Scot Towels in our collection, which would have facilitated quick and easy cleanup of mid-20th-century messes, Scotty always comes through when the 23rd-century Enterprise is in need of a quick fix. –Ellice Engdahl, Digital Collections and Content Manager

Trade Card for "White Cloud," "Mechanic," "Coronet," and "Mikado" Soap, James S. Kirk & Co., circa 1885

James S. Kirk was born in Scotland (not Iowa, like Enterprise captain James T. Kirk) and established his soap company in Utica, New York. He relocated the business to Chicago in 1859 and, by 1900, had built it into one of the largest soap manufacturers in the world, producing 100 million pounds of the cleaner each year. –Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

Tread Power, circa 1885

Gene Roddenberry (1921–1991) considered the United Space (or Star) Ship Enterprise as the main character of Star Trek. But why the name "enterprise"? In response to 1960s counterculture, veterans of World War II, including Roddenberry, did not want anyone to forget the need to ally against evil. The name "enterprise" conjured up associations with action that changed the course of human events. Decades before Star Trek, companies used the term to imply initiative and progress. The Enterprise Manufacturing Company produced an endless-belt tread power, on which a dog, goat, or sheep walked to generate power for myriad uses on family farms. –Debra Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

1896 Riker Electric Tricycle

Andrew L. Riker was a pioneer builder of both electric and gasoline-powered automobiles. He may not have served as first officer aboard a starship like Will Riker of Star Trek: The Next Generation, but Andrew Riker did serve as first president of the Society of Automotive Engineers! –Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

Steam Engine Lubricator, 1882

Star Trek's Leonard McCoy would remind you that he's a doctor, not a locomotive fireman. This steam engine lubricator was patented by African-American mechanical engineer Elijah McCoy, who may have had more in common with Bones' shipmate Scotty. –Jim Orr, Image Services Specialist

Trade Card for Excelsior Botanical Company, circa 1885

The Latin root, excello, meaning "to rise," inspired many companies with aspirations. Excelsior Botanical Company marketed cure-all preparations and "excelsior" became the synonym for packing material made from wood chips or pine needles. All of this happened more than a century before the release of Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, in which Hikaru Sulu commanded the U.S.S. Excelsior starting in 2290. –Debra Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

The Historical Figures of Star Trek

Though the various series and movies of Star Trek are set in the future, those crews and characters sometimes ended up crossing paths with historical figures familiar to those of us stuck here in the 21st century. Image Services Specialist (and Trekkie) Jim Orr shares some objects from our collection that tie to those notables, and explains each Star Trek connection as we continue to celebrate our latest exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, "Star Trek: Exploring New Worlds."

Life Mask of Abraham Lincoln by Clark Mills

In the 1966 Star Trek episode "The Savage Curtain," Captain Kirk and Commander Spock become unwilling participants in an alien experiment to determine which is stronger—good or evil. Their allies included a doppelganger of Kirk's hero, President Abraham Lincoln.

Relief Plaque of "The Last Supper"

In the 1969 Star Trek episode "Requiem for Methuselah," Kirk encounters an ancient, immortal being who claims to have been many notable figures from history, including Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci. Another version of Leonardo da Vinci would appear in the 1997 Star Trek: Voyager episode "Concerning Flight," in which alien arms dealers steal the U.S.S. Voyager's holographic equipment.

Bookplate of Jack London, circa 1905

In the 1992 Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Time's Arrow," Lieutenant Commander Data finds himself stranded in the year 1893 after an encounter with time-traveling aliens. There, he befriends hotel bellhop (and aspiring writer) Jack London.

Portrait of Mark Twain, by Edoardo Gelli, 1904

While attempting to rescue a time-traveling Data from 1893 San Francisco in the 1992 Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Time's Arrow," the crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise accidentally returns with author Samuel Clemens (a.k.a. Mark Twain).

Book, "Opticks: or a Treatise on Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of Light," by Sir Isaac Newton, 4th ed., 1730

Data played a hand of poker against holographic representations of "three of history's greatest minds" in the 1993 Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Descent." Sir Isaac Newton's works include Opticks: or a Treatise on Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of Light.

Ford Motor Company Executive Ernest G. Liebold with Albert Einstein, 1941

Data's poker game with "three of history's greatest minds" also includes a holographic representation of Albert Einstein. Ford Motor Company executive E.G. Liebold posed for this photograph with the real Albert Einstein in 1941.

Amelia Earhart Speaking at the Elks Air Circus, July 11, 1929

Amelia Earhart's mysterious fate has figured into the plots of TV shows ranging from Night Gallery to The Love Boat. Star Trek: Voyager featured Earhart in the 1995 episode "The 37's," explaining her 1937 disappearance as—what else—an alien abduction. (Thanks to Curator of Transportation and fellow Trekkie Matt Anderson for this contribution!)

Jim Orr is Image Services Specialist at The Henry Ford and has seen all 732 episodes (and counting) of every series of Star Trek.

We don’t generally associate Star Trek with historic automobiles (or, for that matter, with any automobiles). The classic original series is set circa 2265-2269, nearly 360 years after the first Model T rolled out of Ford’s Piquette Avenue Plant. By all evidence, Federation citizens in the 23rd century are content to get around by spaceship and shuttlecraft (with the notable exception of the Jupiter 8). But who can blame them for not driving? After all, we’re talking about a universe in which teleportation is a thing. But Star Trek isn’t an entirely auto-free zone. Through the clever storytelling devices of science fiction, Kirk, Spock, and McCoy encounter multiple 20th century American cars over the course of the show.

Ask fans to name their favorite episodes and you’ll likely hear “The City on the Edge of Forever” mentioned several times. The romantic yarn, which closed the first season, finds the crew of the Enterprise in a time-traveling misadventure. Dr. McCoy, less than lucid after an accidental overdose of medication, charges through a temporal gateway into New York City circa 1930. Kirk and Spock follow their ailing comrade and discover that McCoy has inadvertently altered history with serious consequences. Our heroes manage to put things right, but not without considerable anguish on Kirk’s part.

Ford’s 1929 Model AA stake body truck, similar to one seen in “The City on the Edge of Forever.” (THF28278)

The episode features several period automobiles including a 1930 Buick, 1928 and 1930 Chevrolets, and a circa 1930 Ford Model AA truck. Most are in the background, but a 1939 GMC AC-series truck plays a crucial part in the story. In fact, it’s not too much to say that the whole plot depends on it. (Beware of the spoiler at this link.) No, a ’39 truck has no business being on the streets of New York in 1930, but we’ll just let that slide.

The crew returns to a circa 1930 setting in the memorable season two episode “A Piece of the Action.” But this time they’re not on Earth. The Enterprise arrives at the planet Sigma Iotia II, last visited by outsiders before implementation of the Federation’s sacrosanct Prime Directive – barring any interference with the natural development of alien cultures. Kirk and company discover that the planet was indeed contaminated by those earlier visitors. They left behind a book on Chicago gangsters in the 1920s, and the Iotians – a society of mimics – have modeled their planet on that tome, with the expected chaotic results.

Cadillac, the choice of discerning Starfleet officers. (THF103936)

Those industrious Iotians somehow managed to replicate a host of 1920s and 1930s American cars. Look for a 1929 Buick, a 1932 Cadillac V-16, and a 1925 Studebaker in the mix. But the star car undoubtedly is the 1931 Cadillac V-12 used by Kirk and Spock. It’s one of the few times you’ll see Kirk drive, and it makes for one of the episode’s more amusing scenes. Give one point to Spock for knowing about clutch pedals, but take one point away for his referring to the Caddy as a “flivver.” One could quibble with ’30s cars appearing in a ’20s setting – but one should also remember that this isn’t Earth. We can’t expect the Iotians to get all the details right!

It’s also worth taking a look at season two’s final episode, “Assignment: Earth.” The Enterprise travels back in time to 1968 to conduct a little historical research on Earth. They cross paths with the mysterious Gary Seven, an interstellar agent on a mission of his own to prevent the launch of an orbiting missile platform that will – apparently – lead to nuclear war. It sounds like something right out of “Star Wars.” (No, not that Star Wars, this “Star Wars.”)

Based on the Department of Defense cars seen in “Assignment: Earth,” it seems the Pentagon prefers Plymouths. Now why could that be? (THF150740)

It’s all very complicated, but it provides another opportunity to see some vintage wheels. (Well, vintage to us and to the Enterprise crew. To TV audiences in 1968, these were contemporary cars.) Pay attention and you’ll spot a number of government agency vehicles including a 1963 Plymouth Savoy, a 1967 Dodge Coronet, and a 1968 Plymouth Satellite (the latter being particularly apropos for a space series). For those who aren’t Mopar fans, look quickly and you’ll also spy a 1966 Ford Falcon in the episode.

Okay, so no one will ever confuse Star Trek with Top Gear. But, if you keep your eyes peeled, every now and then you’ll find a little gasoline to go along with all of that dilithium. After all, sometimes the boldest way to go is the oldest way to go.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

by Matt Anderson, cars, popular culture, TV, space, Star Trek

Lunchbox Fandom

"Monkees" Lunchbox and Thermos, 1967 (THF92313)

Beaver Cleaver may have carried a plain metal lunch box to school, but lunch boxes with pictures on them have been big business since the days of the Leave It to Beaver television show. Since the 1950s, children have been persuading their parents that they absolutely must have a school lunch box sporting their favorite character. For, to show off a Davy Crockett or a Beatles or a Star Wars lunch box to the world (or to your friends, which meant basically the same thing) when these were popular was simply the essence of cool. And, for young children, this is still true today -- only the characters and the lunch box materials have changed.

The first true pictorial lunch box was created in 1950, when a painted image of Hopalong Cassidy was applied to a steel lunch box and matching thermos bottle. In the first year of its production, Nashville, Tennessee manufacturer Aladdin Industries sold an unprecedented 600,000 of these, at a (not inexpensive) retail cost of $2.39.

Three years later, American Thermos introduced a fully lithographed steel lunch box depicting Roy Rogers and Dale Evans. Sales of these reached an astonishing 2 1/2 million the first year, and these types of lunch boxes -- with pictures covering all sides -- immediately became the industry standard. The pictorial lunch box industry was off and running, and competition between companies became fierce. Over the next three decades, steel lunch boxes featured dozens of television shows, movies, popular musicians, sports stars, special events, fads, and famous places.

Pictorial lunch boxes made of waterproof vinyl wrapped around cardboard first came on the market in 1959. Their shiny, purse-like qualities lent themselves to pictorial themes marketed to girls, like the highly popular Barbie lunch boxes, introduced in 1961. Unfortunately, these could not stand up to heavy use -- their seams split and their corners crushed easily.

During the 1970s, vocal parents and school administrators began to complain that metal lunch boxes were to blame for students' injuries-enough so that, by 1987, lunch box manufacturers were forced to cease using steel in favor of safer (and cheaper) plastic.

Hopalong Cassidy, 1950 (THF92292)

William (Bill) Boyd brought this fictional character to life, first at the movies then on television in 1950. "Hoppy" became the first television hero for many American children. This show precedes the major era of television westerns ushered in by Gunsmoke in 1955, when the huge popularity of westerns signaled Americans' nostalgia for a simpler past and their need for clear-cut heroes and villains during an uncertain time.

Tom Corbett: Space Cadet, 1954 (THF92296)

On television from 1950 to 1955, this early science fiction show was a spin-off of a comic book and teen adventure novel series. The show, which took place in a futuristic world of scientific marvels, was made somewhat believable by the technical expertise of Willy Ley, an associate of Werner von Braun.

Rocky and Bullwinkle, 1962 (THF92316)

Like The Simpsons, Rocky and His Friends disguised adult entertainment in the form of a cartoon. The show aired from 1957 to 1963 during prime time, and with its clever, tongue-in-cheek scripts, it could well be considered the most subversive show about the Cold War of its time. From 1964 to 1973, the show continued under the new name The Bullwinkle Show, and it has since been entertaining children and adults alike through reruns and videos.

"Sock It To Me," 1968 (THF92319)

Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In was a mid-season replacement in 1968, and no one expected it to be very popular. That's probably why its producers were able to experiment with virtually a new format-a rapid-fire pace using video editing and no narrative structure-and a new kind of hip topicality couched in one-liner jokes. Although its novelty is lost to us today -- the one-liners seem hopelessly outdated, even old-fashioned -- catch-phrases like "Sock It to Me" have become instantly recognizable cultural icons, while the show's short skits, slapstick humor, and use of topical material helped to revolutionize television.

Happy Days, 1976 (THF92322)

A mid-season replacement in 1974, this show had its origins in a 1972 Love, American Style episode and took great advantage of the popularity of the film American Graffiti. The first television show to take place in an era where television had already been invented, this version of the 1950s was embraced especially by young people who had not known the real decade first-hand. The show's true star was "The Fonz," who may have seemed like an unlikely role model but became television's biggest star for several years.

Sesame Street, 1983 (THF92308)

From the time this show premiered on PBS in 1969, it quickly established itself as the most significant educational program in television history. Envisioned as an entertaining show for preschoolers-especially those from underprivileged backgrounds-to help prepare for school, Sesame Street incorporated the rapid-fire style of both television commercials and television programs like Laugh-In. With its consistently high quality and humor geared toward both children and their parents, this show continues to be extremely popular today.

Donna Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

20th century, TV, school, popular culture, music, movies, food, childhood, by Donna R. Braden

Emmy Award-winning The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation with Mo Rocca is a weekly celebration of the inventor’s spirit, from historic scientific pioneers throughout past centuries to the forward-looking visionaries of today. Each episode tells the dramatic stories behind the world’s greatest inventions and the perseverance, passion and price required to bring them to life.

The fourth season of The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation with Mo Rocca marks its 100th episode on April 28, 2018. We asked a few of the curators you've seen on screen and who work hard behind the scenes to share some of their favorite memories and artifacts from the show so far.

One of my favorite Innovation Nation episodes to work on featured the 1964 Moog synthesizer prototype—a singular artifact that impacted the history of electronic music. I remember being on set very early in the morning with Mo and scrambling to figure out how to play “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” on our Minimoog synthesizer in time for the cameras to roll. I think it was a success, though no record deals have arrived yet!

Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communication & Information Technology

I’m so glad we opened our 1923 Canadian Pacific snowplow for the first season of Innovation Nation. Not only did it help illustrate the work required to keep a railroad operating year-round, it provided an opportunity for us to photograph the snowplow’s interior. Now everyone can share the experience through our Digital Collections!

Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content

For me, nothing tops the segment on Henry Ford’s 1896 Quadricycle. Because we have an operating replica, Mo and I could experience the artifact in a way that’s different from simply looking at – or even touching – something. No doubt Henry had his frustrations building the original but, based on our ride, he had some fun along the way, too!

Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

One of my favorite moments was walking into the Lovett Hall ballroom to see Susana Hunter’s vibrant improvisational quilts spread out on the gleaming wooden floor. I had seen these quilts many times before. But in this setting, the group looked absolutely luminous—and Susana’s joyful, creative spirit shown through every quilt.

Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

quilts, quadricycle, railroads, technology, music, TV, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation

Ideas in Action

This feature originally ran in the June-December 2016 edition of The Henry Ford Magazine.

TV, The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation, technology, flying, inventors, The Henry Ford Magazine

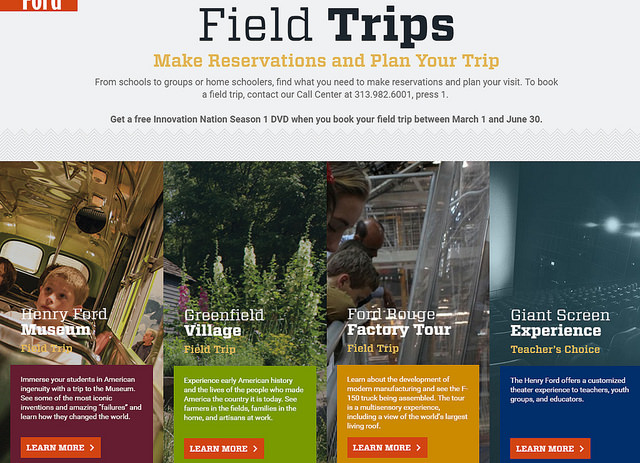

The Key to Successful Field Trips at The Henry Ford

The education department at The Henry Ford has the pleasure of working with teachers who do an excellent job of planning their field trips. They each bring their schools and classrooms here for a multitude of reasons but they all agree that preparing their students is the key to a successful field trip. The more preparation that students receive increases their comfort and excitement, leading to a more powerful learning experience. This “prep work” includes both the logistics of the visit and linking what they do and see at The Henry Ford to what they are learning in the classroom.

This spring, we are making two major investments to help teachers better prepare their students prior to visiting us:

The Henry Ford has a newly designed website to help teachers easily find the many options for customizing a field trip to meet specific curriculum and scheduling needs. Each venue has its own page with logistical assistance for your trip and our most popular curriculum-aligned activities to use before, during and/or after your visit. If you don’t find the perfect resource there, additional activities can be found in our Resource Bank.

Each teacher who books a field trip now through June 30, 2016 will receive a season one DVD of The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation. In this Emmy-award winning TV series, host Mo Rocca meets up with our curators to learn the significance of our most famous artifacts and experiences – and lets viewers in on some hidden gems. Then, co-hosts visit with today’s innovators, linking the past with the present and future. Some of these innovators are even the same age as our field trip visitors! The clips can tie classroom curriculum to the artifacts and experiences at The Henry Ford. For example, a high school U.S. History class visiting Henry Ford Museum should watch our segment on the Rosa Parks Bus. An elementary class studying inventors should check out the Wright Brothers and Thomas Edison segments before coming to Greenfield Village.

The clips can tie classroom curriculum to the artifacts and experiences at The Henry Ford. For example, a high school U.S. History class visiting Henry Ford Museum should watch our segment on the Rosa Parks Bus. An elementary class studying inventors should check out the Wright Brothers and Thomas Edison segments before coming to Greenfield Village.

If you are interested in your own copy of The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation Season 1 DVD, it is available in our gift shops and online. You can also access individual clips of both season 1 and season 2 on The Henry Ford’s YouTube channel.

Check your local listings to see when The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nationis airing on CBS in your area.

We believe that equipping teachers with new features on our revamped website and episodes from the TV show will help to better prepare students for a visit to The Henry Ford so that they can be inspired by the stories of American ingenuity, resourcefulness and innovation. After all…THEY are the ones who will produce future innovations to help shape a better future.

Catherine Tuczek is Curator of School and Public Learning and Phil Grumm is Curator of Digital Learning at The Henry Ford. Want to be the first to know about our latest resources and special offers? Then sign up for our OnLearning newsletter.

TV, The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation, educational resources, education, field trips, by Phil Grumm, by Catherine Tuczek