Posts Tagged women's history

When thinking about the celebrated figures in decorative arts history, one first thinks of individuals like Thomas Chippendale, Duncan Phyfe, and Gustav Stickley in furniture, Paul Revere and Tiffany and Company in silver, and Josiah Wedgwood in ceramics. All these prominent figures have something in common—they all are men. There are few celebrated female leaders in the decorative arts. This may be due to the scholarly focus on great men, to the detriment of women, until recent years.

Cover of Tried by Fire by Susan Frackelton, 1886. / THF627718

One of the most important and underrecognized women in decorative arts history was Susan Frackelton (1848–1932). She was a founder of the field of women’s china painting in the 1870s and 1880s. She was also a catalyst in transforming that pastime into a profession with the evolution of china painting into art pottery in the 1890s. Unlike her more famous peers, Susan Frackelton earned her living and supported her family on the proceeds of her publishing, teaching, and collaborations with like-minded artists.

Susan Frackelton faced many challenges in her personal and professional life. In many ways, she was a trailblazer for the modern, independent woman. Only in recent years have her contributions been recognized. Like other major figures in the decorative arts, including Thomas Chippendale, she is best remembered for a publication, her 1886 Tried by Fire. In the introduction, she states, “If the rough road that I have traveled to success can be made smoother for those who follow, or may hereafter pass me in the race, my little book will have achieved the end which is desired.”

Why Was China Painting a Means for Women’s Liberation?

Many factors fueled the growth of amateur china painting in late-19th-century America. As America became wealthier after the Civil War, women of the middle and upper middle classes gained more leisure time for personal pursuits. China painting became a socially acceptable pastime for women because it allowed them to create decorative objects for the home. Further, the influence of the English Aesthetic movement and later the Arts and Crafts movement advocated that the creation of art should be reflected in the home. By the 1870s and 1880s, wealthy women were freer to leave the confines of the home through organizations that they set up to create and exhibit their work.

What Is China Painting?

Pitcher, 1890–1910, decorated by an amateur china painter. / THF176880

This pitcher is a good example of the work of an amateur china painter. The artist would take a “blank”—a piece of fired, undecorated, white porcelain, in this case a pitcher made by the English firm Haviland—and paint over the glaze. These blanks could be purchased in multiples at specialty stores. One of the most prominent of these was the Detroit-based L.B. King China Store. It was founded in 1849 and closed during the Great Depression, about 1932. According to a 1913 advertisement, the retailer sold hotel china, fine china dinnerware, cut glass, table glassware, lamps, shades, art pottery, china blanks, and artists materials. Elbert Hubbard, founder and proprietor of the Roycrofters, a reformist community of craft workers and artists that formed part of the Arts and Crafts movement, wrote enthusiastically about the products of the L.B King China Store: “The store is not only a store—it is an exposition, a school if you please, where the finest displays of hand and brain in the way of ceramics are shown.” A woman seeking to learn about china painting could literally walk into the L.B. King Store and walk out with paints, blanks, and a manual like Frackelton’s Tried by Fire and start painting her own china.

The pitcher above is part of a large group of serving pieces in our collection. Also in our collections is a full set of china decorated by a young woman and her friends who learned china painting at what is now Michigan State University. They decorated the dinnerware service in preparation for the young woman’s wedding in 1911. According to family history, the young woman purchased the blanks at the L.B. King Store.

How Did China Painting Evolve in the Late 19th Century?

During the 1870s, Cincinnati was the center of American china painting. The movement was led by two wealthy women, Maria Longworth Nichols (1849–1932), who later founded the Rookwood Pottery, and her rival, Mary Louise McLaughlin (1847–1939). Both studied with European male ceramic artists who had made their way to Cincinnati. Both evolved from amateur status into extraordinary artists, who moved from painting over the glaze to learning how to throw and fire their own vessels, create designs, and formulate glazes for their vessels. This all occurred during the late 1870s, following a display of ceramic art at the Women’s Pavilion of the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Both sought to outdo each other in the formulations of glazes. It is generally believed McLaughlin was the first to learn the technique of underglaze decoration, although Nichols later claimed that she was the first to do so. Nichols’ most important achievement was in creating the Rookwood Pottery in Cincinnati in 1880. It was essentially the first commercial art pottery company in America, and it led the way in the development of new techniques that were widely imitated by other firms. Rookwood and its competitors began to hire women to decorate ceramics, opening a new livelihood for women less well off than Nichols and McLaughlin.

Vase, 1902, decorated by Grace Young, Rookwood Pottery Company, Cincinnati, Ohio. / THF176709

Vase, 1917, decorated by Lenore Asbury at the Rookwood Pottery Company in Cincinnati, Ohio. / THF176918

Tile, 1910–1920, made by the Rookwood Pottery Company in Cincinnati, Ohio. / THF176941

Essentially, through the pastime of china painting, a new industry, art pottery, came into being by 1900. Under the influence of popular magazines like the Ladies’ Home Journal and House Beautiful, Americans eagerly acquired art pottery. In fact, tastemakers like the young architect Frank Lloyd Wright filled his houses with art pottery. He considered it very much part of his total aesthetic. Through the first three decades of the 20th century, art pottery was considered a must in any well-furnished American home. It only fell out of fashion in the 1930s, when the Great Depression drastically altered lifestyles.

How Does Susan Frackelton’s Story Fit into All of This?

Susan Stuart Goodrich Frackelton was a contemporary of both Maria Longworth Nichols and Mary Louise McLaughlin, born in 1848 like Maria Longworth Nichols, and just a year older than Mary Louise McLaughlin. Unlike either of these women, she came from a modest background. Her father was a brick maker in Milwaukee, and she was raised in a middle-class environment. Susan began her artistic career studying painting with the pioneer Wisconsin artist Henry Vianden. In 1869, she married Richard Frackelton and eventually raised three sons and a daughter.

Richard’s business was importing English ceramics and glass and was relatively successful. Within a few years, however, the business began a sharp decline and Susan stepped in to help. She later said that she learned about American taste in ceramics and business while working with her husband. Concurrently, she began to experiment with china painting, applying her experience in painting with Henry Vianden. She was essentially self-taught, unlike her contemporaries in Cincinnati. Through publications, she was aware of what was going on in the field. She was also aware of the innovations of Mary Louise McLaughlin in glazes, and by the late 1870s was experimenting in underglaze painting herself.

Frackelton’s contributions to china painting began in 1877, when she opened Frackelton’s Decorating Works in Milwaukee. She trained young women in the art of china painting. By 1882 she opened a related business called Mrs. Frackelton’s Keramic Studio for Under and Overglaze, where she sold her own work, wares made by her students, commercial china, and glassware, as well as painting supplies. Like Detroit’s L.B. King store, she created a one-stop shop for young women interested in exploring china painting and, later, art pottery.

Title page, Tried by Fire, 1886. / THF627720

Frackelton made a national name for herself in 1886 with the publication of Tried by Fire. It differed from other manuals for china painters in that it was written by a teacher for beginning students. Frackelton’s conversational style and advice on not expecting too much too soon appealed to readers and the book became a best seller, reprinted in two revised editions in 1892 and 1895. As a teacher, Frackelton had no equal in the world of art pottery. She advocated that both wealthy and poor women could enjoy the art of china painting: “Beauty is the birthright of the poor as well as the rich, and he lives best who most enjoys it.”

Color plate from Tried by Fire, 1886. / THF627772

Color plate from Tried by Fire, 1886. / THF627773

Color plate from Tried by Fire, 1886. / THF627775

Color plate from Tried by Fire, 1886. / THF627774

Pitcher, 1890–1910, decorated by an amateur china painter. Note that the botanical decoration on this pitcher is similar to the Tried by Fire color plates. / THF176879

Another major innovation was the development of a patented gas-fired kiln, first offered in the advertising section of Tried by Fire. By 1888 she was granted a second patent for a new and improved version.

Advertising section of Tried by Fire showing Frackelton’s portable gas kiln. / THF627793

By 1890 Frackelton was a well-known figure and was noted for displaying her work in international exhibits. In 1893 she won eight awards for her work in a competition held at Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition. Additionally, she became renowned for her work in a variety of ceramic media, especially for her blue and white salt-glazed stoneware. She also worked to create new and easier-to-use paints for decoration. She went so far as to organize the National League of Mineral Painters in 1892, an organization “aimed to foster a national school of ceramic art and provide a link between china painters throughout the country.”

By the late 1890s, Frackelton’s reputation was secure, as were her finances. In 1897 she divorced Richard Frackelton and moved to Chicago and spent much of her time lecturing and promoting ceramic art. She collaborated with several ceramic artists, including the now famous George Ohr, a unique artist who called himself “the mad potter of Biloxi.” Together, they created several highly unusual pieces, now in the collections of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

In her later years, Frackelton moved away from working in ceramics, preferring to return to painting and working as an illuminator of manuscripts. However, Frackelton’s promotion of the ceramic arts made her one of the most admired female artists in America in the first decade of the 20th century. Susan Frackelton was a remarkable figure in American ceramics, justifiably earning her status as one of the prominent figures in the decorative arts and certainly in broadening the role of women in American society.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

Illinois, Wisconsin, 20th century, 19th century, women's history, teachers and teaching, making, furnishings, entrepreneurship, education, decorative arts, ceramics, by Charles Sable, books, art

Denise McCluggage

Denise McCluggage at the wheel of her Osca S187 at Bahamas Speed Weeks, 1959. / 1959NassauSpeedWeek_080

It’s one thing to cover auto racing for a living. It’s quite another to live the racing you cover. Journalist and race driver Denise McCluggage earned a unique place in racing history not only for her reporting on a golden era of motorsport, but for her participation in it too.

McCluggage was born in Eldorado, Kansas, in 1927. She traced her love of cars to a moment when, at six years old, she saw a Baby Austin parked on the street and decided she had to have one. Alas, even a letter to Santa Claus didn’t make that dream come true. But McCluggage realized another childhood dream—a career in journalism—that was ignited when she published her own neighborhood newspaper at age 12.

After high school, McCluggage studied at Mills College in Oakland, California, where she earned degrees in economics, philosophy, and politics. She began her journalism career at the nearby San Francisco Chronicle. McCluggage moved to the other side of the country in 1954 and went to work for the New York Herald Tribune. She joined the paper’s sports department, where her assignments included reports on auto racing.

McCluggage developed a lasting friendship with fellow driver Sir Stirling Moss. The two are pictured here at Bahamas Speed Weeks in 1959. / THF134439

As she covered the sport, McCluggage began to take a deeper interest in racing. She bought a British MG TC and began running in small sports car club events. McCluggage didn’t have any formal lessons, but she proved a natural on the track. Her experiences in competition brought unusual insight to her reporting and—at a time when women weren’t welcomed in pits or garages—gave her better access to the male drivers she covered. McCluggage’s efforts on the track gained her greater respect in the macho world of 1950s and 1960s motor racing, and she earned a reputation as someone who did what she wrote about. (When she wasn’t writing or racing, McCluggage was often on the slopes where she became an accomplished skier—another sport she frequently covered.)

With her trademark polka dot helmet, McCluggage earned an impressive list of victories and became one of the top female racing drivers of her time. She won Nassau Ladies Races in 1956 and 1957, and she took the checkered flag at the Watkins Glen Grand Prix Ladies Race in 1957. McCluggage placed first in the GT category at the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1961, and she finished first in her class at the 1964 Monte Carlo Rally.

McCluggage won the GT class at the 1961 Sebring 12-Hour Race. Her #12 Ferrari 250 is at center right. / THF246594

McCluggage’s journalism career flourished as well. In 1958 she collaborated in the founding of Competition Press. The racing magazine eventually broadened its focus to general car culture and changed its name to Autoweek, but it remains active today as a digital publication. McCluggage contributed columns to Autoweek for the rest of her life. She also wrote several books, including The Bahamas Speed Weeks, The Centered Skier, American Racing: Road Racing in the ’50s and ’60s, and By Brooks Too Broad for Leaping—a collection of some of her pieces for Autoweek.

In later years, McCluggage seemed to split her time between giving awards—she was an honorary judge at the prestigious Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance—and receiving them. She was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 2001, and into the Sports Car Club of America Hall of Fame in 2006.

Denise McCluggage passed away in 2015. At the time of her death, she was remembered as much for her achievements behind the wheel as for her accomplishments behind the typewriter, and she was recognized as one of the trailblazing women in racing. Time has not diminished her triumphs; McCluggage was posthumously inducted into the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America in 2022.

Mark Twain said “write what you know.” Denise McCluggage struck a similar chord in a quote published in Sports Illustrated in 2018: “Racing was something I wanted to do, so it was something I wanted to cover.” The automotive world is richer because she did both.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Remembering Al Unser, Sr. (1939-2021)

- Frank Kulick: Early Ford Racer

- 2012 Ford Fiesta Rally Car, Driven by Ken Block in "Gymkhana Five"

- Auto Racing Virtual Meeting Backgrounds: Featuring Driven to Win

21st century, 20th century, women's history, sports, racing, race car drivers, cars, by Matt Anderson

Suits for the Stars: Spacesuits of Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Cocooned within 21 layers of synthetics, neoprene rubber, and metalized polyester films, Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin was well protected from the airless moon’s extremes of heat and cold, deadly solar ultraviolet radiation, and even the off chance of a hurtling micrometeorite. / Photo by Neil Armstrong/NASA

Cocooned within 21 layers of synthetics, neoprene rubber, and metalized polyester films, Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin was well protected from the airless moon’s extremes of heat and cold, deadly solar ultraviolet radiation, and even the off chance of a hurtling micrometeorite. / Photo by Neil Armstrong/NASA

It’s possibly the most recognizable image in all of human history: Buzz Aldrin on the surface of the moon, his left arm drifting up as if checking the time during a stroll through the park.

The photo sticks in the imagination more than any image of sleek rockets on the launchpad or metallic modules landing on an inhospitable world. Perhaps it’s the casual, individual bravado oozing off Aldrin’s puffed-up frame that truly captures the essence of humans pushing past the ultimate boundary: space.

And yet the spacesuit is rarely the star of the human spaceflight epic. Which is a shame, since this was the most intimate component of the engineering endeavor that landed man on the moon 50 years ago—intimate also because the surprising winner of NASA’s spacesuit contract was a spinoff of Playtex, the underwear manufacturer which still makes items from bras to feminine products to this day.

Playtex made everyday women’s girdles like those shown in this ad before making an unlikely jump to producing clothing for space travel to the moon in the 1960s. / Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“The suits that other companies provided were stiff, they were bulky, they couldn’t fit the narrow confines of the mission parameters,” said Nicholas de Monchaux, professor of architecture at University of California Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design and writer of a deeply researched book called Spacesuit: Fashioning Apollo.

At the core is the idea of the “human factor,” often overlooked by engineers in their quest to reach the lunar surface. The Saturn V rocket and the lunar module were exquisitely engineered, with sharp, clean lines governed by the unchanging forces of physics: thrust, gravity, air resistance. But the same equations are blurred when dealing with the human form. “The human body doesn’t operate from first principles,” said de Monchaux.

In the race to win the initial suit contract, companies such as David Clark Company, which made the Mercury mission spacesuits, and Hamilton Standard, a division of conglomerate United Aircraft, produced concepts informed by their decades-long experience with high-altitude pressure suits. These options proved much more difficult to maneuver than the suit produced by ILC Dover, the Playtex spinoff whose patented “convolutes” included rubber identical to that filling Playtex’s girdle molds, as well as nylon tricot and webbing taken from the supplies feeding its brassiere assembly lines.

The Apollo spacesuit designed by ILC Dover and worn on the moon had 21 layers, 20 of which were created with synthetics made by chemical giant DuPont. Familiar household names like nylon, Lycra, and Teflon were found in various layers, a fact DuPont proudly advertised at the time.

In 1966, events came to a head when a new ILC spacesuit had to compete once more against prototypes from Hamilton Standard and David Clark. Test subjects using the competing suits had trouble moving around, operating switches, and fitting in and out of the mock landing module. Imagine if Aldrin and Neil Armstrong had touched down successfully on the moon only to not fit through the hatch to step on the surface!

Though each competing suit was custom fitted, only the 21-layer ILC Dover soft suit was sewn by hand by a hotshot crew of the best seamstresses taken from Playtex’s sewing floor—eschewing paint-by-numbers engineering in favor of highly personalized, artisanal craftsmanship. Each spacesuit created by the ILC Dover team bore a laminated photograph of the astronaut it belonged to in order to create a connection to the person whom they were literally keeping alive with their craftsmanship.

Arlene Thalene of ILC Dover inspects a spacesuit’s mylar insulation layers. / Photo courtesy of ILC Dover, LP

Their knowledge, gained by fashioning bras and girdles for women’s activewear, proved indispensable to creating a superior product. The material itself was co-opted: “The rubber that made the suit was literally from the same tank that was, originally at least, supplying the girdle-making that had made Playtex’s fortune,” said de Monchaux.

ILC Dover employee Velma Breeding installs a bladder into a boot. / Photo courtesy of ILC Dover, LP

The ILC Dover suit bested the others in official NASA tests, but the systems-engineering bureaucracy of the Apollo program was still skeptical of an untested spinoff holding such a critical contract. When again faced with competition for the last phase of Apollo’s missions (numbers 14-17), the ILC Dover team even resorted to filming a test subject playing football in a pressurized suit for several hours. “And, as became clear on watching the films, the suited subject’s attempts were at the very least equivalent to those of an engineer in shirtsleeves and slacks who joined him on the field,” wrote de Monchaux. “ILC Dover, née Playtex, had won the Apollo game.”

A composite of the final drawings from ILC Dover depicts (from right to left) an Apollo 11 spacesuit’s pressure garment assembly, a suit with its Thermal Micrometeoroid Garment (TMG) attached, and an astronaut wearing a suit with TMG outer cover, gloves, and helmet. Once securely attached to the spacesuit’s inner pressure garment, the multilayered TMG protected astronauts against micrometeoroid impacts, solar and galactic radiation, thermal conduction, and abrasion, and also provided fire protection. / Drawings courtesy of ILC Dover, LP

Dressed for Health

More than 50 years after the Apollo 11 astronauts donned their spacesuits on the moon, I’m sitting in an office at hygiene and health giant Essity’s facility in North Carolina trying to pull on what looks like your average thick knee-high black socks. Kevin Tucker, the global technical innovations manager for a division of Essity, chuckles while I struggle with the fabric as it tightens like a vice. Tucker is in charge of the company’s work with NASA to develop a compression suit for astronauts returning from space. He points out as he puts the socks away that future NASA astronauts will wear something with twice the compression power.

Essity’s bread and butter is making compression garments for people with venous and lymphatic diseases. That’s when the body has issues with pumping fluids against the pull of gravity, causing symptoms from lack of feeling in extremities to loss of consciousness. It’s something we have all experienced to some degree, said Tucker. “If you’re sick in bed with the flu and you’re lying down for a long period of time and you have to go run to the bathroom, the first step you usually take you end up on your nose.”

Astronauts also have trouble with fluid control. When they first get up into space and gravity is no longer a factor, fluids are pumped more into their torso and head. That’s why new arrivals to the International Space Station have puffy faces. After a while, the body adjusts and pumps less to accommodate the lack of gravity. But the problem rears its head again upon re-entry and the rapid reintroduction to gravity. At that point, the body’s fluid pumping is weakened, and astronauts often have to be carried out of the capsule. “This sudden rush of fluid away from the head and heart down into the legs can affect your consciousness,” said Tucker. That’s something his team is trying to change.

To help NASA, Essity is applying its expertise in designing compressive socks, sleeves, and girdles to create a compression suit future astronauts would wear on re-entry to prevent or avoid the sudden redistribution of fluids to the lower extremities upon return to Earth’s gravity. When Tucker lays out the current design on a table, it’s a crisscross of tight black fabric and a few zippers, woven in a way reminiscent of those fancy yoga pants that have sheer patterns.

Health giant Essity is currently working with NASA to create a compression suit that astronauts will wear upon re-entry to Earth. The garments, shown separately here for illustrative purposes, will prevent or avoid the sudden redistribution of fluids to the lower extremities upon return to Earth’s gravity. / Photo courtesy of Essity

It’s slated to be the first layer of gear NASA astronauts will put on as they prepare to splash down—so getting stuck as you pull on the suit is simply not an option. Another “soft” consideration is that the astronauts will have to wear these for hours in a seated, upside-down position, and tests of earlier designs irritated subjects’ bent knees. The newest version of the compression suit comes slightly pre-bent at the joint, making it more comfortable.

The Human Factor and What’s Next

The human body was not meant for space travel, and the soft problems it presents require innovative solutions with intimate knowledge of the human body. Some of those challenges (and ways suits can help) are listed below.

Vacuum: Exposed to the vacuum of space, a body’s fluids would start boiling away as the body puffs up. A spacesuit protects you—but, be warned, it will puff up, too.

Temperature: Outside the International Space Station, the temperature swings wildly from 250 to -250 degrees Fahrenheit. But with no atmosphere to transfer heat or cold, a well-insulated spacesuit keeps you comfy.

Radiation: Above the protection of the Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field, cosmic radiation is the most consistent health concern. A spacesuit provides very limited protection—as does the space station.

Lack of Gravity: Low or no gravity makes muscles atrophy, bones lose density, and fluids redistribute. NASA is working on it.

Unfortunately, the human body is not always something the engineering culture of rocket scientists takes into account. “We’re still thinking about the engineering and the propulsion systems and the vehicle, but we’re not thinking enough about the pink, squishy things that are in the middle of that vehicle,” said Diana Dayal, who did a year-long apprenticeship at the National Space Biomedical Research Institute (NSBRI). Funded by NASA’s Human Research Program, NSBRI, which closed in 2017, was NASA’s lead partner in space biomedical research and provided hands-on lab opportunities for young scientists, engineers, and physicians such as Dayal to access careers in human spaceflight.

On future, longer space missions, the human factor will be amplified. New challenges will arise from the long stint in low gravity. “The deconditioning of your bones and muscles is going to be an unavoidable problem on a three-year Mars mission,” said Dayal. “How are you supposed to send people to Mars and expect them to set up a habitat?”

Astronaut Neil Armstrong—shown here aboard the Apollo 11 Lunar Module Eagle, the first crewed vehicle to land on the moon—later quipped that his spacesuit was one of the most widely photographed spacecrafts in history. Decades later, he sent a note to the team that designed the spacesuit, complementing it and calling it “tough, reliable and almost cuddly.” You can see the “cuddly” spacesuit worn by Armstrong, held by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, on their collections website. / Photo by NASA / Edwin E. Aldrin Jr.

One of the solutions being explored is enhancing the spacesuit with an exoskeleton—essentially empowering the humans by linking them to a stronger robotic carapace. This is a good idea, but the prototype Dayal saw at NASA’s Johnson Space Center was so large and cumbersome, it was hard to imagine it on an average person.

“It’s so cool that you basically have all this circuitry that simulates nerves, but at the same time, who did you build this for? Who’s going to wear it?” They were questions posed by Dayal’s group, she said, pointing out that current designs lack sufficient modularity to adjust to different body types.

While the lessons learned in developing the soft Apollo spacesuit decades earlier may have to be revisited as we look to longer missions, it’s also an opportunity to push the boundaries of design. “All of your constraints are out the window; everything is a variable,” said Dayal. “If anything, designing for space should help us better design for Earth.”

Fedor Kossakovski is a freelance science writer and producer. This post was adapted from an article in the June–December 2019 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

The Henry Ford Magazine, making, women's history, engineering, design, fashion, by Fedor Kossakovski, space

Quiet & Loud Protest

Photo by Curatorial Staff of The Henry Ford

When you think of the word “protest,” what does it mean to you?

- Marching at a rally with a sign?

- Participating in a “walk out” at school?

- Boycotting companies?

- Wearing a shirt or hat with a message?

- Correcting people on their biases?

- Donating money to organizations?

- Civil disobedience?

A new temporary exhibit now on view in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, Quiet & Loud Protest, explores this question by demonstrating the ways that protest can be both loud and quiet. Throughout history, people have found different ways to advocate for change, whether marching in the streets or finding quieter ways to be an ally. Both are valuable in drawing attention to injustices. The exhibit draws together a small selection of recent acquisitions that showcase how artist-activists have used graphics to demand change and organize communities. The content of the exhibition is replicated in this post (with slightly expanded descriptions) for those unable to see it in person.

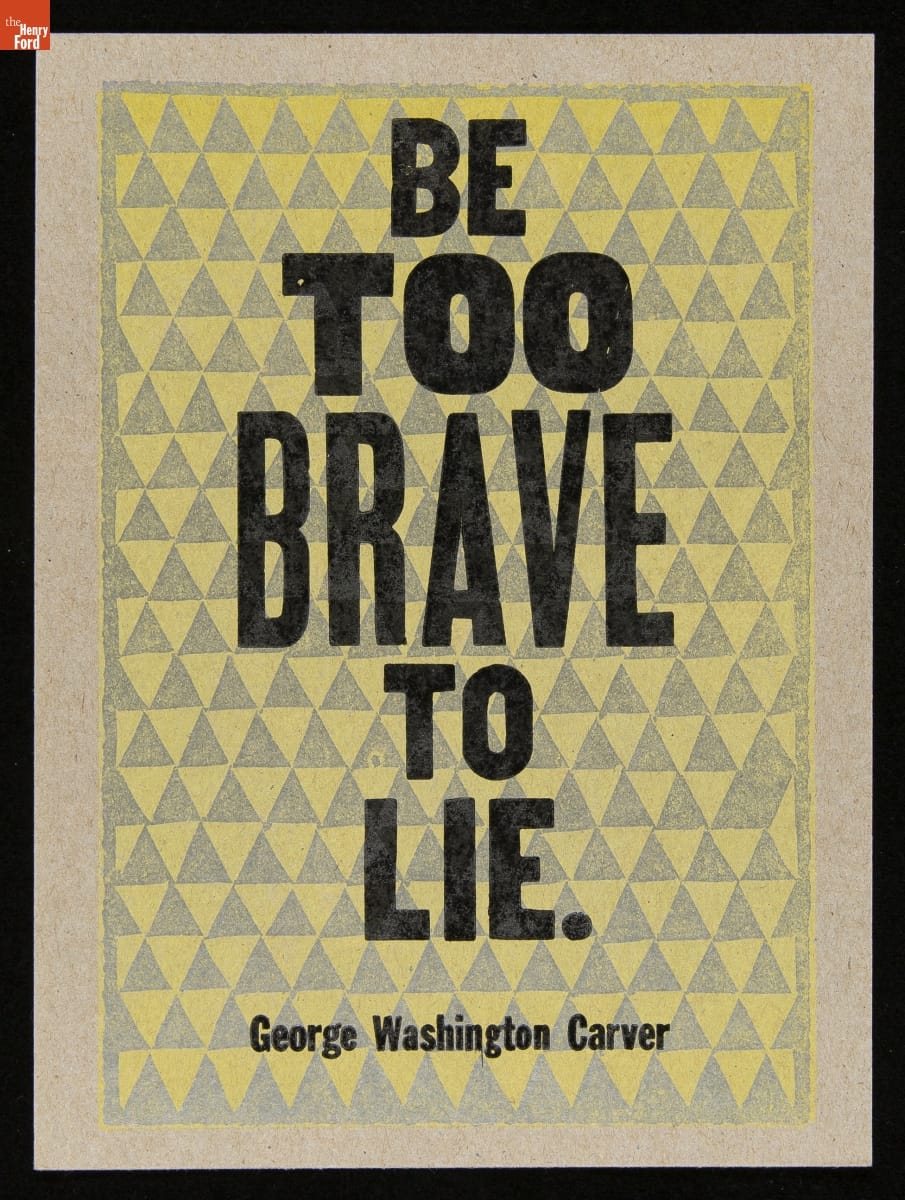

Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr.

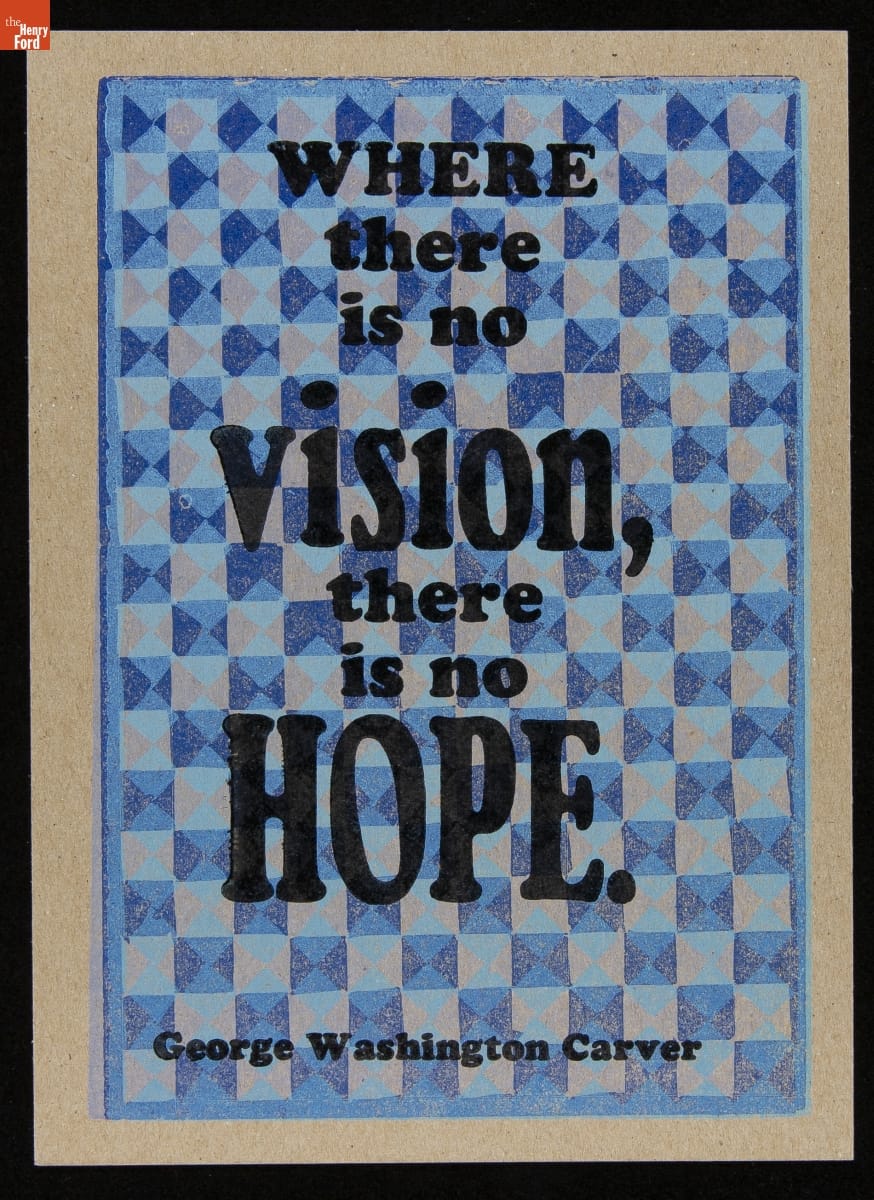

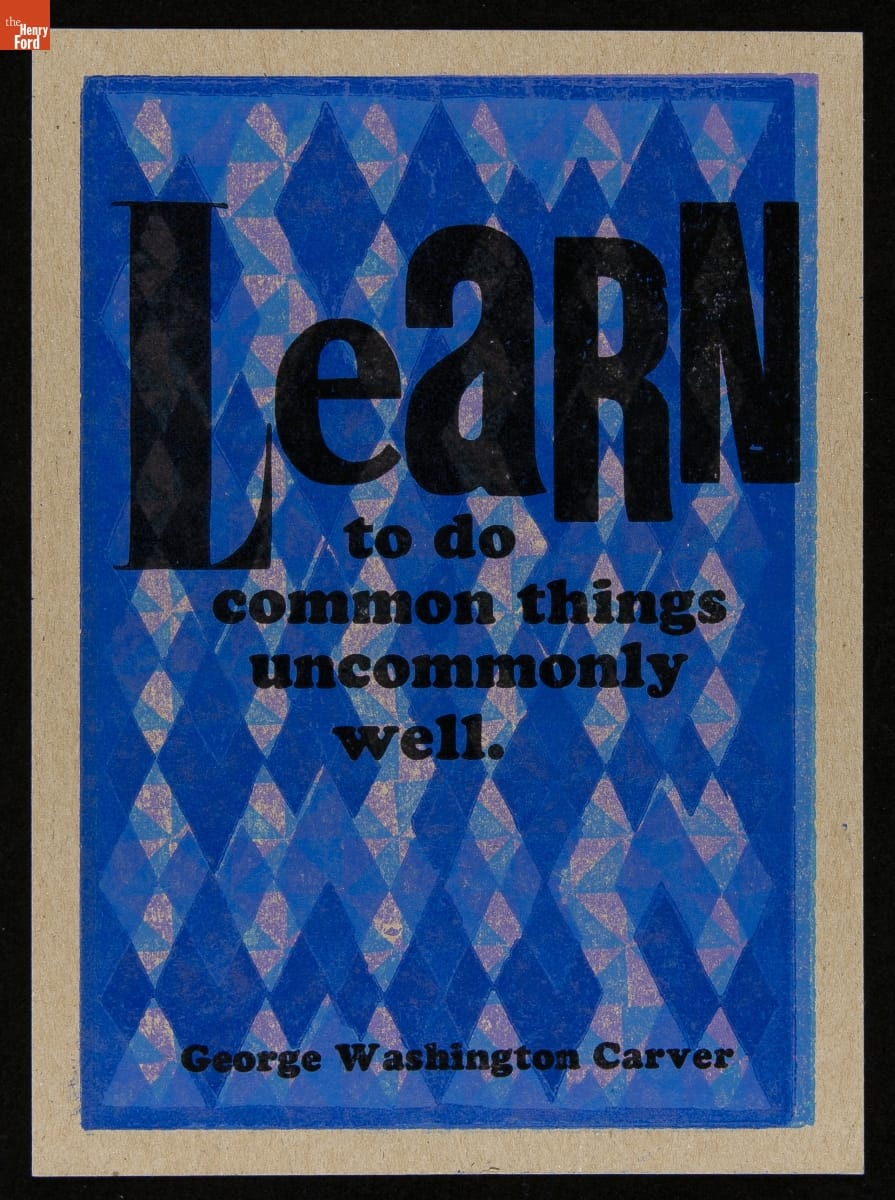

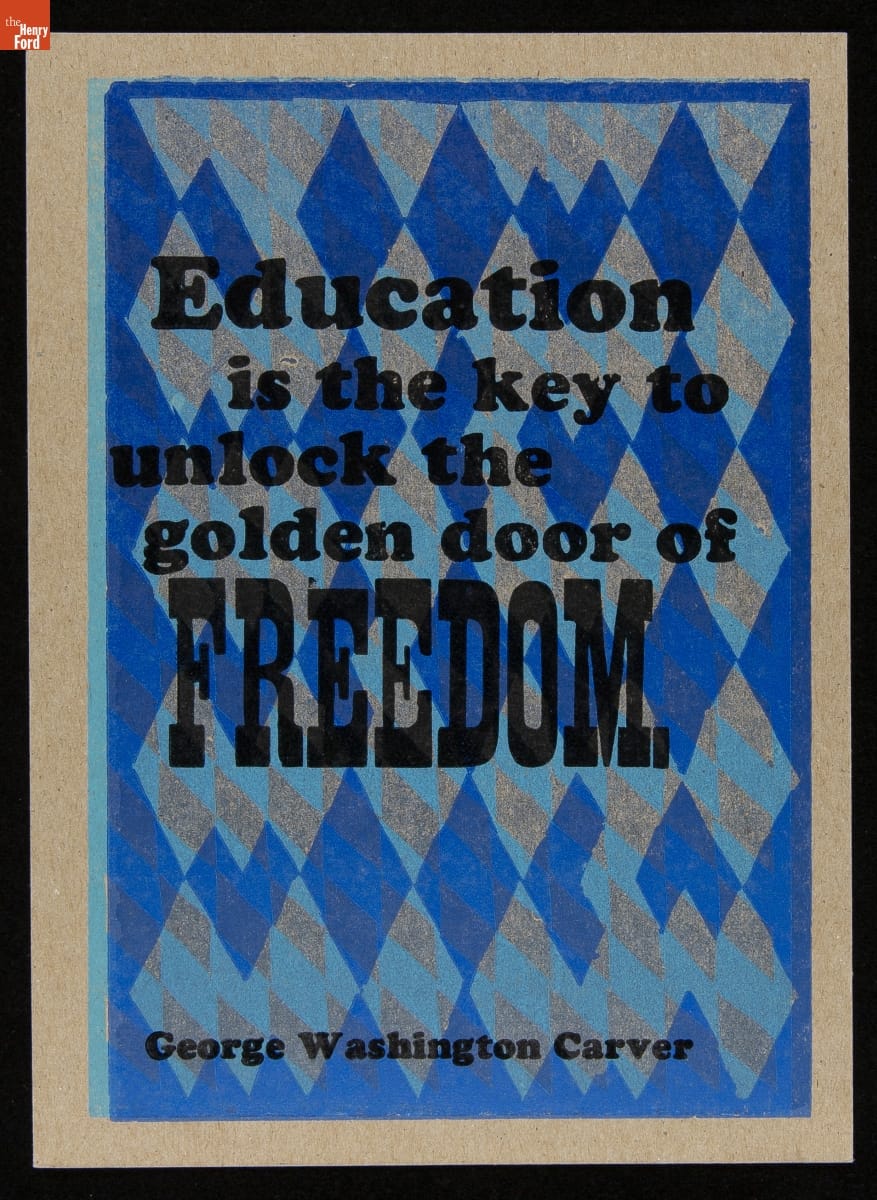

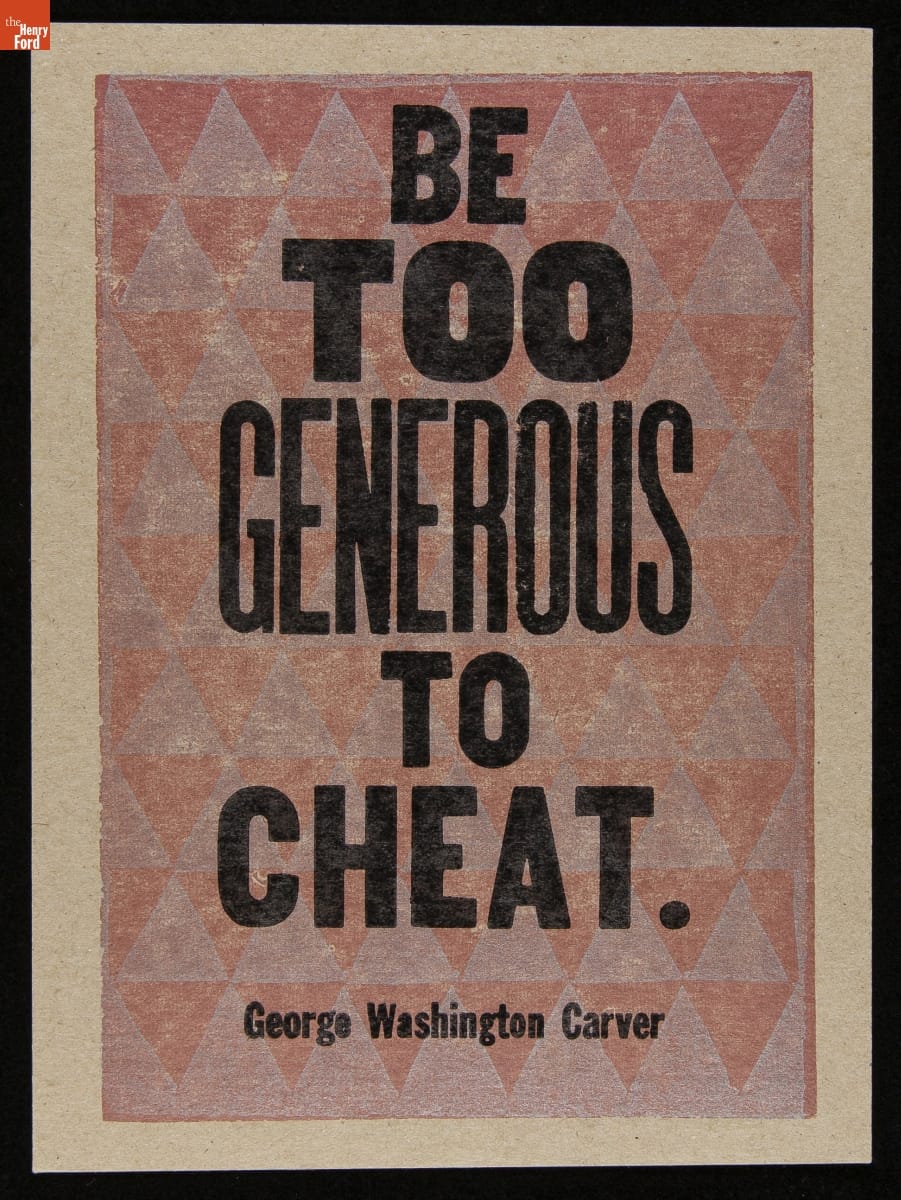

Amos Paul Kennedy Jr. has generously donated several prints to the collections of The Henry Ford. These examples feature quotes attributed to George Washington Carver and Rosa Parks—two advocates for change who are prominent in our collections. / THF626953 (top), THF626939 (bottom)

These letterpress prints are by Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr., who relocated to Michigan from the South in 1963 with his parents. In junior high, he experienced racism from teachers who presumed he was uneducated and poor because he was Black.

At the age of 40, Kennedy visited Colonial Williamsburg while on vacation with his family and was so enamored with the letterpress and bookbinding demonstrations being given by historical reenactors that he went home and began to take classes at a community print shop. His love for the medium grew to the point where he made the decision to leave his career as a corporate computer programmer at AT&T so that he could focus on printmaking full time.

Letterpress prints by Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr./ THF626947 (top), THF626949 (bottom)

He went on to earn an MFA in Fine Arts and taught in university art programs. When Kennedy left academia, he adopted the historical role of an iterant printer, travelling through the American South to different print shops, learning about print media and developing his style over the course of many years. Kennedy sometimes describes himself as a “humble Negro printer” and wears bib overalls with a pink dress shirt. By doing this, Kennedy confronts people with their biases, causing them to question race, language use, and class. In 2013, Kennedy moved to Detroit, where he operates Kennedy Prints today.

Letterpress prints by Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr. / THF626943 (top), THF626941 (bottom)

Kennedy is known for his prolific output of vibrant letterpress prints that address cultural biases and social justice issues. Many of his prints feature quotes by Black civil rights activists and abolitionists, scientists and innovators, and literary figures, as well as traditional African proverbs. In an interview with the Library of Congress in January 2020, Kennedy said:

“People sometimes classify me as a political artist, and I find that amusing because when I was young, I was told that everything you do is political […] I print the things that reflect the way that I want the world to be. I think that people who say they are not political in their work fail to recognize that ‘not being political’ is a political act.”

Kennedy refuses to call himself an artist and sells his work at affordable prices to make it more accessible. Thanks to the power of the multiple, Kennedy can use printmaking to spread messages of hope widely—to reflect exactly the type of world that he wants to live in.

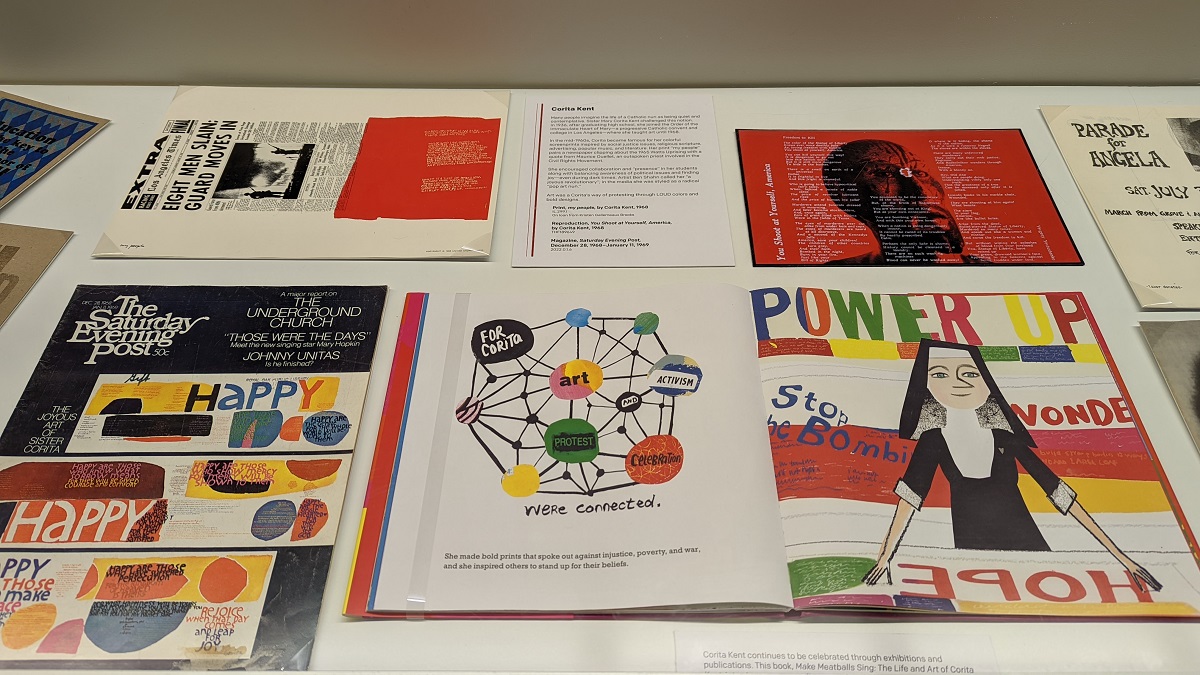

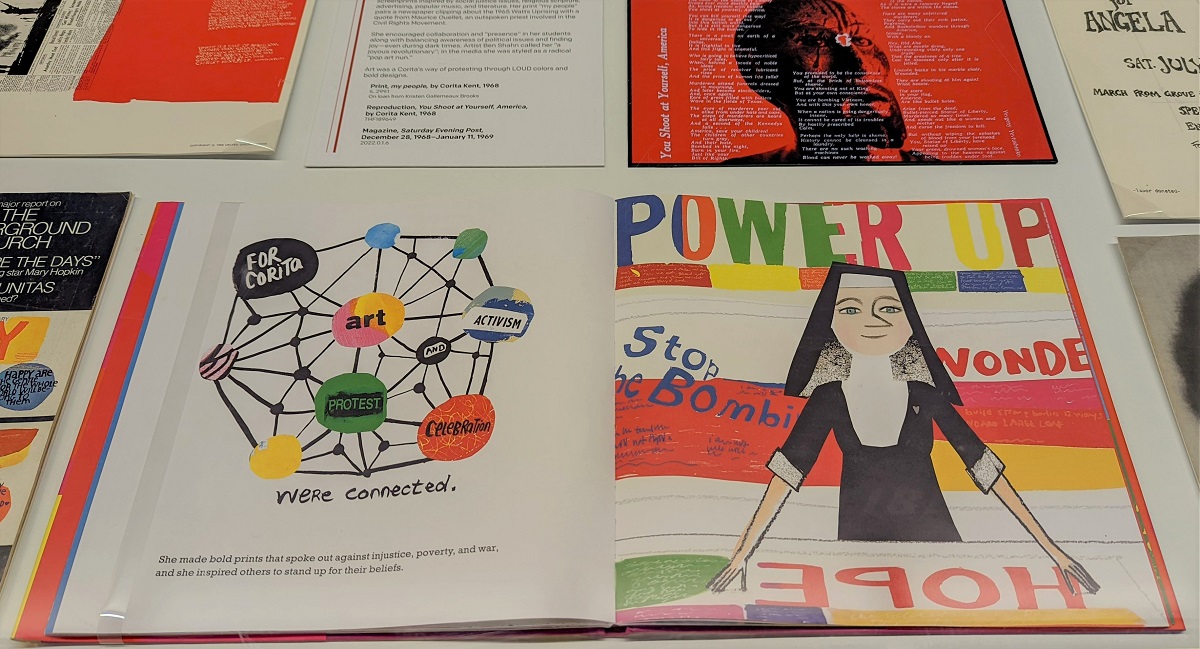

Corita Kent

Photo by Kristen Gallerneaux

Many people imagine the life of a Catholic nun as quiet and contemplative. Sister Mary Corita Kent challenged this notion. In 1936, after graduating high school, she joined the Order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary—a progressive Catholic convent and college in Los Angeles—where she taught art until 1968.

In the mid-1960s, Corita became famous for her colorful screenprints inspired by social justice issues, religious scripture, advertising, popular music, and literature. Her most celebrated prints are text-heavy and vibrant, layering blocks of bright color and DayGlo ink with high-key photographic imagery and words that twist around the page.

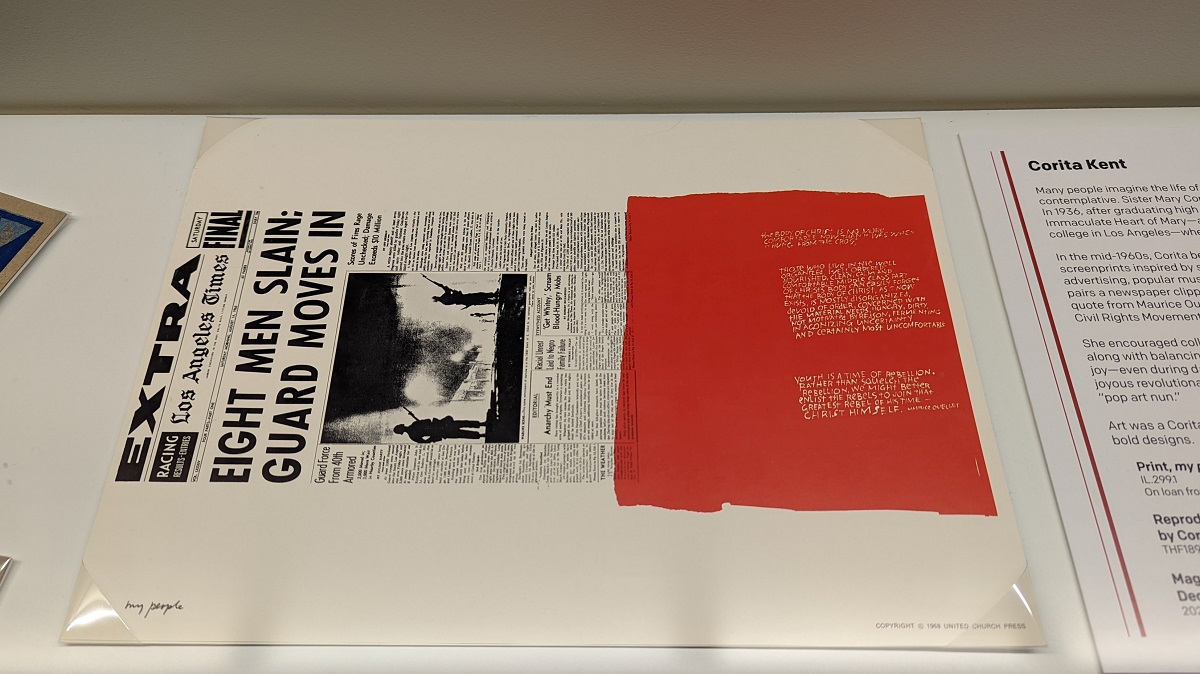

Detail of Quiet & Loud Protest exhibit with Corita Kent’s “my people” print. / Photo by Kristen Gallerneaux

Her print “my people” pairs a newspaper clipping about the 1965 Watts Uprising with a quote from Maurice Ouellet, an outspoken priest involved in the Civil Rights Movement in Selma, Alabama. Part of the quote Corita included reads: “Youth is a time of rebellion. Rather than squelch the rebellion, we might better enlist the rebels to join that greatest rebel of his time—Christ himself.” And in an oral history, Corita herself said: “I feel that the time for physically tearing things down is over. It’s over because as we stand and listen, we can hear it crumbling from within.”

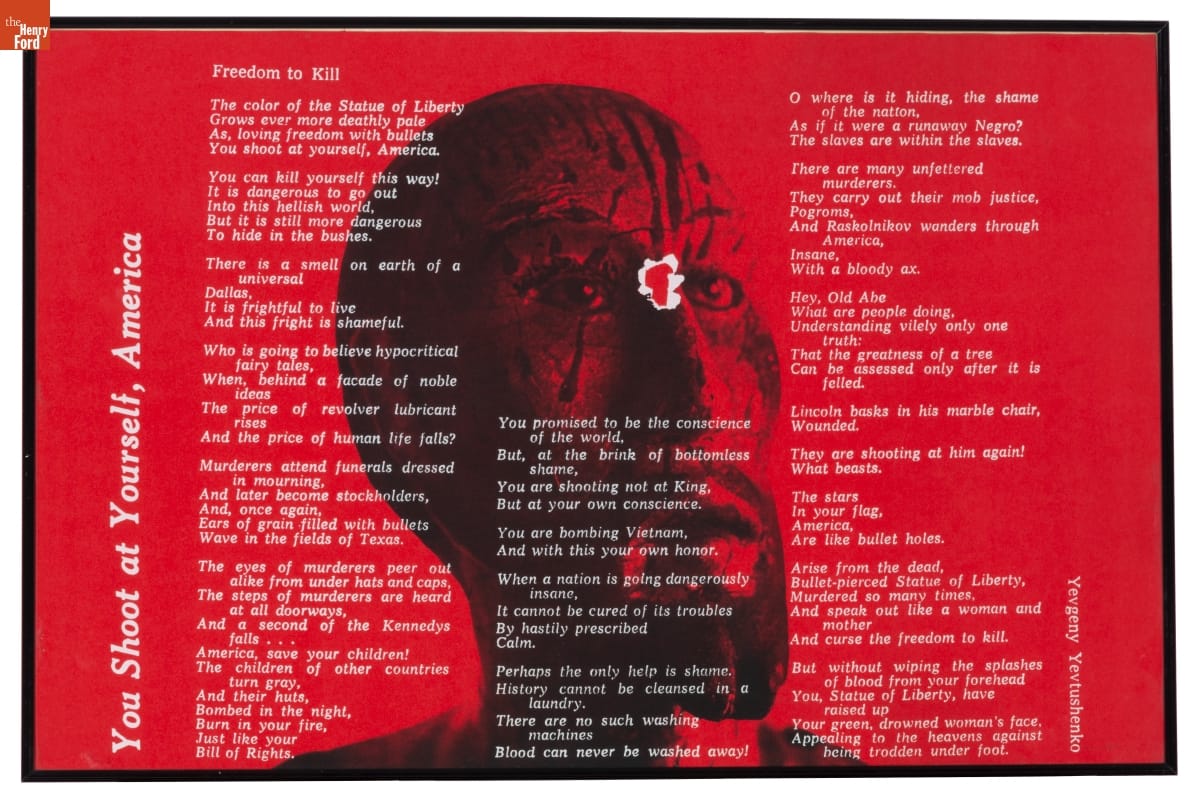

Corita Kent’s print “You Shoot at Yourself, America” was created in response to the 1968 assassination of Robert F. Kennedy. It features a poem by Yevgeny Aleksandrovich. / THF189649

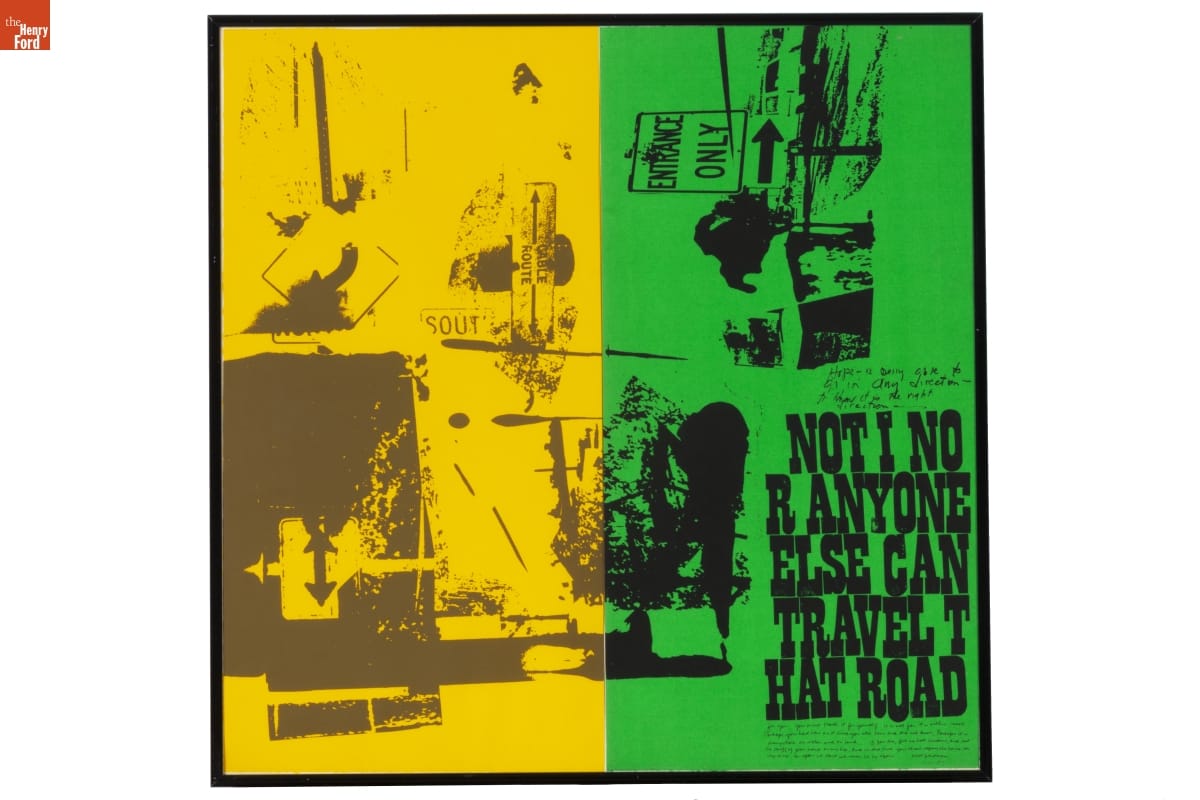

Corita Kent’s print “Road Signs (Part 1 & 2)” features text excerpted from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. / THF189650

Corita encouraged collaboration and “presence” among her students and encouraged them to balance awareness of political issues with finding joyful moments—even during dark times. Many important designers and creative thinkers visited her classroom, including Buckminster Fuller and Charles and Ray Eames. Artist Ben Shahn once called her “a joyous revolutionary” and in the media she was styled as a radical “pop art nun.”

Art was a Corita’s way of protesting through LOUD colors and bold designs.

During the height of Corita’s fame, the Catholic Church was reassessing many of its traditions, striving for unity and modernization under Vatican II. And yet not everyone agreed. In 1967, the Los Angeles archdiocese and Archbishop James McIntyre claimed the Immaculate Heart Community’s (IHC’s) approach to education was “communist” and referred to Corita’s work as being “blasphemous.” When the IHC sisters were ordered to end the liberating “renewal innovations” they had come to enjoy—or be asked to leave their teaching posts—many asked to be released from their vows and left in protest.

Corita’s decision to leave the order came a little sooner. In 1968, exhausted from an intense schedule and censorship from the church, Corita took a sabbatical. At the end of her time away, she left the Order and moved to Boston. There, she continued to receive commissions and to create art such as painting the Boston Gas Company’s tanks and designing the iconic “Love” postage stamp.

Corita Kent continues to be celebrated through exhibitions and publications. This book, Make Meatballs Sing: The Life and Art of Corita Kent, introduces young audiences to her story. / Photo by Kristen Gallerneaux

Angela Davis

Angela Davis is an activist, educator, and scholar who was a member of the Communist Party USA and the Black Panther Party. In 1970, Davis was placed on the FBI’s “Most Wanted” list. Guns registered to her name were used in a fatal attempt to free the Soledad Brothers during a courtroom trial. Davis was not present at the event. She fled police, fearing unfair treatment. After her capture, she spent 18 months in prison until being cleared of charges.

For some people, Davis is a controversial figure who believed in non-peaceful protest. To others, she is an inspiration as an outspoken supporter of women’s and civil rights, prison reform, and socialism. In recent years, she came out as lesbian and advocates for LGBTQ+ rights as well as those of Palestinian people.

The following artifacts relate to the impact of Angela Davis’s activism, past and present..jpg?sfvrsn=cc0a3601_2)

Vermont S. Galloway—a WWII veteran—made this “FBI Captures Angela” screenprint at Westside Press to advocate for Davis’s freedom. Galloway was fatally shot by the Los Angeles Police Department in 1972. / THF277084

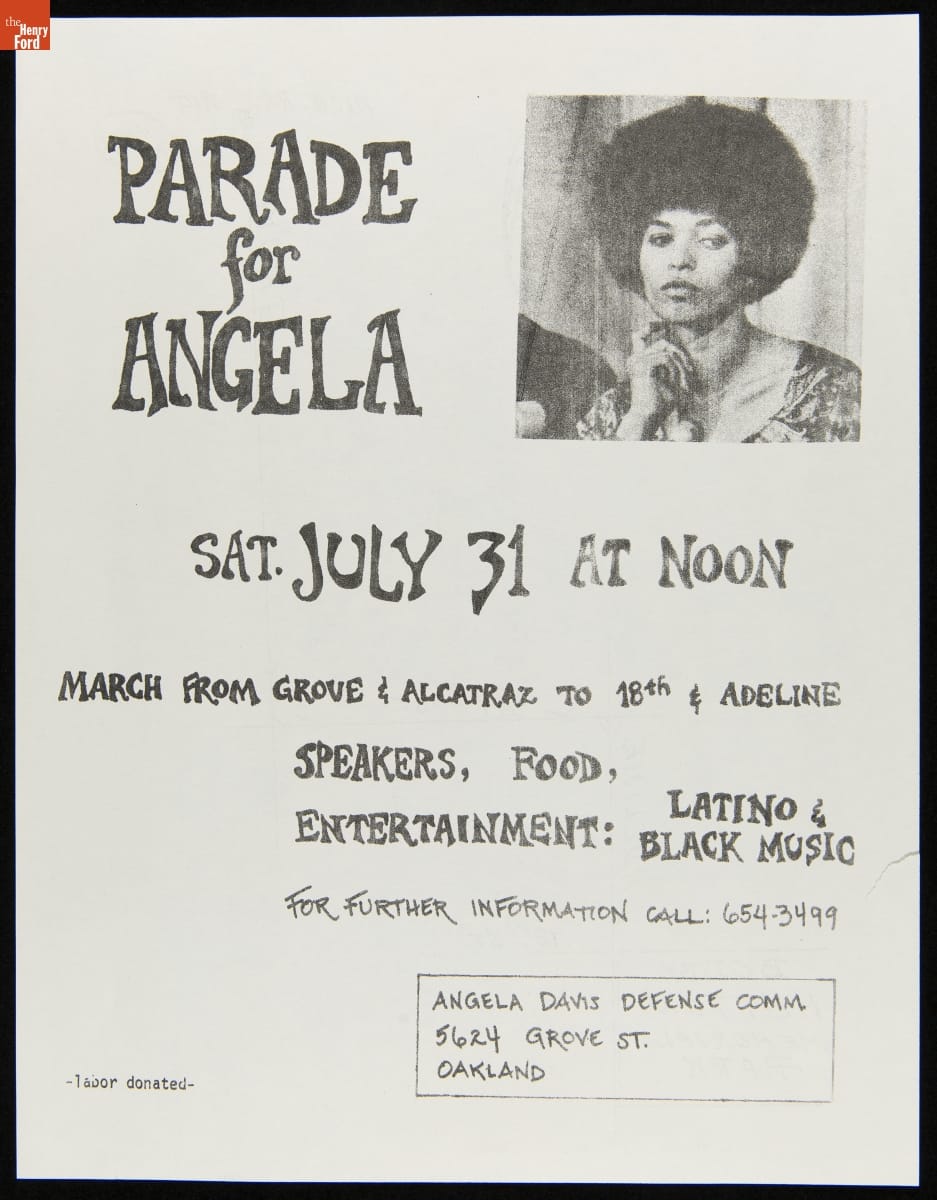

A parade flier documents the international “Free Angela” movement. The reverse side shows the planned route through Oakland, California. / THF627614

“13 Questions…” was the first interview with Davis while she was incarcerated. Her discussion with Joe Walker covers topics such as the surveillance of Black people, legal corruption, solidarity, and dismal prison conditions. / THF627594

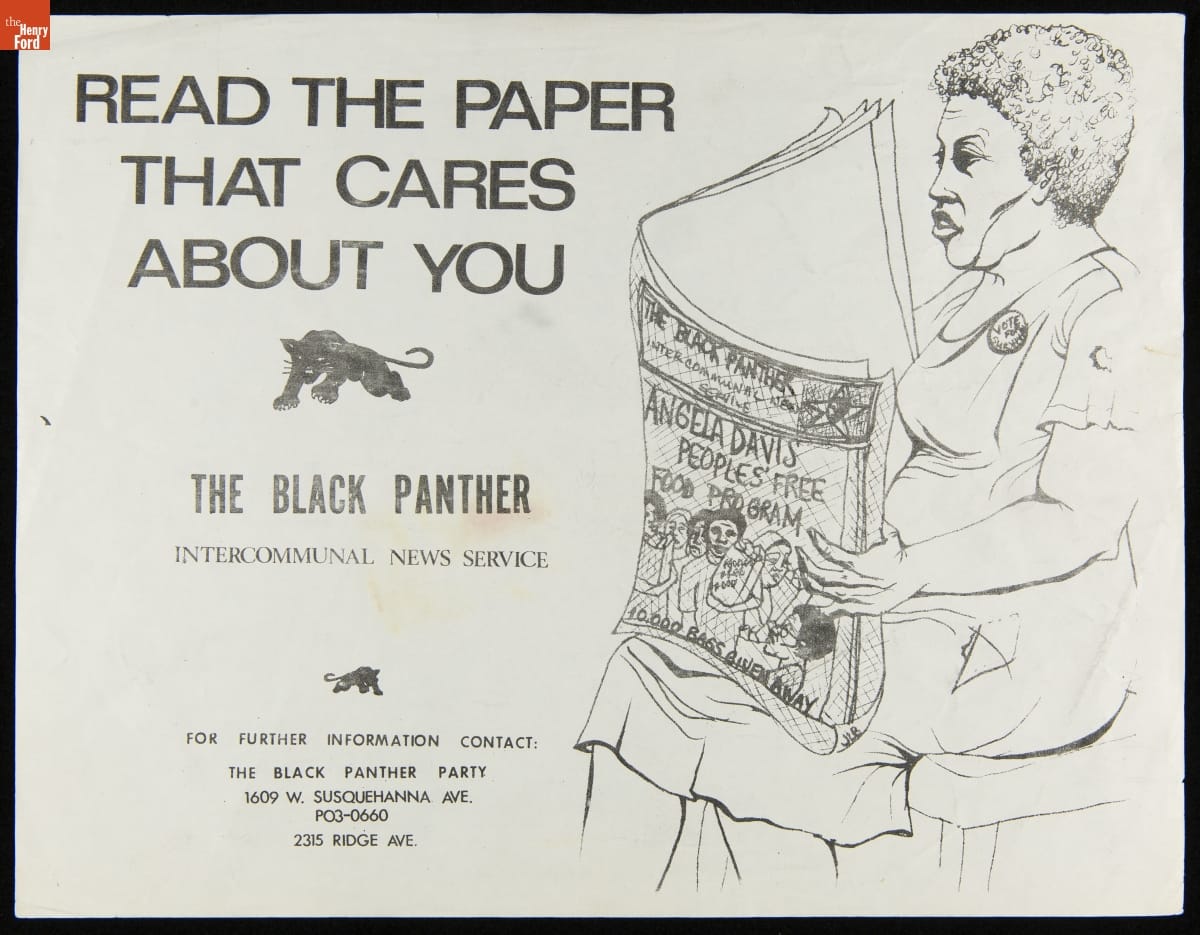

An illustration by Akinsanya Cambon advertises the Black Panther Party’s newspaper and the “Free Breakfast for Children Program,” using Davis’s name. / THF627598.jpg?sfvrsn=c40a3601_2)

Davis appears in a poster by Tongva artist Mer Young for the Amplifier Foundation. This poster shows the continued impact of Davis’s legacy and was created to encourage Black and Indigenous voting in the 2020 election. / THF626361

Listening to Our Community

In 2021, The Henry Ford began to seek community feedback for ways to update and improve our permanent exhibit With Liberty and Justice for All. This work is continuing in 2022.

Stories of movements, social innovators, and political history are difficult to fully capture in museum labels. There is always too much to tell in 100 words or less. To address this, throughout the display of this exhibit, we will be inviting several community partners to contribute their own labels, in their own voices, to foreground the issues they believe matter the most.

By the Curatorial Staff of The Henry Ford. Quiet & Loud Protest is on view in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation until March 31, 2022.

Civil Rights, art, making, women's history, African American history, Henry Ford Museum, printing

Women in Agricultural Work and Research

Woman with Machine Spinning Soybean Fiber into Soylon Thread, March 1943 / THF272609

One of The Henry Ford’s main collecting areas is agriculture and the environment. Last fall, Processing Archivist Hilary Severyn shared highlights from our archives around women in agricultural work and research as part of our History Outside the Box program on Instagram. If you missed it, you can check out her selections, which range from women working on soybean research to the Women’s Land Army to Rachel Carson’s fight against pesticides, in the video below.

archives, History Outside the Box, Rachel Carson, soybeans, environmentalism, women's history, agriculture, by Ellice Engdahl, by Hilary Severyn

Honoring Rachel Carson’s Legacy with Citizen Science

Trained scientist Rachel Carson and wildlife artist Bob Hines conduct research off the Atlantic coast in the early 1950s. The two formed an extraordinary partnership, which brought awareness of nature and conservation to the forefront. / Photo courtesy U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service / public domain

We live in an era where environmental sustainability, social responsibility, and renewable resources are keywords for how to live our lives and operate our businesses.

But it wasn’t always this way. In the early 1960s, writer and biologist Rachel Carson was one of the lone voices sounding the alarm that the rapid, destructive changes we were making to our own environment were having disastrous consequences.

With her groundbreaking 1962 book Silent Spring, which exposed the damage caused by indiscriminate use of pesticides manufactured by powerful chemical companies, Carson showed that she was a scientist motivated by a sense of responsibility to serve the best interests of the wider community. Carson’s eloquence reminded us that we are all part of a delicately balanced ecosystem, and by destroying any piece of it, we risk destroying the whole system. It would become unsustainable.

Rachel Carson holding a copy of Silent Spring in June 1963. / THF147928, detail

Thanks to Carson’s passion and perseverance, a movement of ecological awareness was born. Her work is credited with giving birth to the modern-day environmental movement. Other direct results were the banning of the pesticide DDT and the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

In an era of “living better through chemicals,” Rachel Carson was a changemaker who brought our awareness to the effects we had on our environment. But she also knew that we could be part of the solution. One way people carry on her legacy today is by acting as citizen scientists.

While Rachel Carson was a trained scientist and biologist working toward the greater good, a citizen scientist is a nonscientist who works with the scientific community to affect positive change. By paying attention to our environment and taking an interest in the science behind sustainability, we all can make a difference. Here are some ways you can become involved yourself.

At Home

It was a friend of Rachel Carson who raised an alarm about bird die-offs in her backyard and prompted Carson to write Silent Spring—proof that big change can start small. Here are a couple of ideas worth considering in your sustainability quest at home.

- Join the annual Great Backyard Bird Count at birdcount.org. The count is a great way to get kids involved with nature.

- Use your smartphone to help scientists gather data on animal populations. You can count Costa Rican wildcats at Instant Wild (instantwild.zsl.org) or share observations on your local wildlife at iNaturalist.org.

In Your Community

Look for opportunities for neighborhood involvement—you’ll stay socially connected and help your community at the same time.

- Use resources like greenamerica.org to find and support businesses and brands that are striving toward sustainability.

- Start a community garden. It’s a great way to shift away from packaged, processed foods and to get to know your neighbors. National Garden Clubs (gardenclub.org) helps coordinate the interests and activities of state and local garden clubs in the U.S. and abroad.

- Participate in crowdsourced data gathering like noisetube.net, which measures noise pollution, or createlab.org, which trains artificial intelligence to identify smoke emissions.

In Your Workplace

If you are motivated to make a difference, become an advocate for sustainability and social change within your company. Going green is a differentiator that gives businesses a leg up on recruiting and marketing.

- Recycle office waste, implement inventory controls (which prevent unnecessary purchases and wasteful spending), or research tax credits for becoming energy efficient at energy.gov, the website of the U.S. Department of Energy.

- Let your company’s unused computing power contribute to scientific research projects at scienceunited.org.

You can find even more inspiration to take action by browsing our website for artifacts related to Rachel Carson, artifacts related to environmentalism, and blog posts related to environmentalism.

This post is adapted from “Sustainability at Stake,” an article written by Linda Engelsiepen for the June–December 2020 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Rachel Carson, women's history, The Henry Ford Magazine, nature, home life, environmentalism, by Linda Engelsiepen

What Have We Been Collecting at The Henry Ford?: A Peek at Recent Acquisitions

The Henry Ford’s curatorial team works on many, many tasks over the course of a year, but perhaps nothing is as important as the task of building The Henry Ford’s collections. Whether it’s a gift or a purchase, each new acquisition adds something unique. What follows is just a small sampling of recent collecting work undertaken by our curators in 2021 (and a couple in 2020), which they shared during a #THFCuratorChat session on Twitter.

In preparation for an upcoming episode of The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation, Curator of Domestic Life Jeanine Head Miller made several new acquisitions related to board games. A colorful “Welcome to Gameland” catalog advertises the range of board games offered by Milton Bradley Company in 1964, and joins the 1892 Milton Bradley catalog—dedicated to educational “School Aids and Kindergarten Material”—already in our collection.

Milton Bradley Company Catalog, “Welcome to Gameland,” 1964. / THF626388

Milton Bradley Company Trade Catalog, “Bradley’s School Aids and Kindergarten Material,” 1892. / THF626712

We also acquired several more board games for the collection, including “The Game of Life”—a 1960 creation to celebrate Milton Bradley’s centennial anniversary that paid homage to their 1860 “The Checkered Game of Life” and featured an innovative, three-dimensional board with an integrated spinner. “The Game of Life,” as well as other board games in our collection, can be found in our Digital Collections.

Board games recently acquired for use in The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation. / THF188740, THF188741, THF188743, THF188750

This year, Katherine White, Associate Curator, Digital Content, was thrilled to unearth more of the story of designer Peggy Ann Mack. Peggy Ann Mack is often noted for completing the "delineation" (or illustration) for two early 1940s Herman Miller pamphlets featuring her husband Gilbert Rohde's furniture line. After Rohde's death in 1944, Mack took over his office. One commission she received was to design interiors and radio cases for Templetone Radio. The Henry Ford recently acquired this 1945 radio that she designed.

Radio designed by Peggy Ann Mack, 1945. / Photo courtesy Rachel Yerke

Peggy Ann Mack wrote and illustrated the book Making Built-In Furniture, published in 1950, which The Henry Ford also acquired this year. The book is filled with her illustrations and evidences her deep knowledge of the furniture and design industries.

Making Built-In Furniture, 1950. / Photo courtesy Katherine White

Mack (like many early female designers) has never received her due credit. While headway has been made this year, further research and acquisitions will continue to illuminate her story and insert her name back into design history.

Katherine White also worked this year to further expand our collection of Herman Miller posters created for Herman Miller’s annual employee picnic. The first picnic poster was created by Steve Frykholm in 1970—his first assignment as the company’s internal graphic designer. Frykholm would go on to design 20 of these posters, 18 of which were acquired by The Henry Ford in 1988; this year, we finally acquired the two needed to complete the series.

Herman Miller Summer Picnic Poster, “Lollipop,” 1988. / THF626898

Herman Miller Summer Picnic Poster, “Peach Sundae,” 1989. / THF189131

After Steve Frykholm, Kathy Stanton—a graduate of the University of Cincinnati’s graphic design program—took over the creation of the picnic posters, creating ten from 1990–2000. While The Henry Ford had one of these posters, this year we again completed a set by acquiring the other nine.

Recently acquired posters created by Kathy Stanton for Herman Miller picnics, 1990–2000 / THF626913, THF626915, THF626917, THF626921, THF189132, THF189133, THF189134, THF626929, THF626931

Along with the picnic posters, The Henry Ford also acquired a series of posters for Herman Miller’s Christmas party; these posters were created from 1976–1979 by Linda Powell, who worked under Steve Frykholm at Herman Miller for 15 years. All of these posters—for the picnics and the Christmas parties—were gifted to us by Herman Miller, and you can check them out in our Digital Collections.

Posters designed by Linda Powell for Herman Miller Christmas parties, 1976–1979 / THF626900, THF189135, THF189137, THF189136, THF189138, THF626909, THF626905

Thanks to the work of Curator of Communications and Information Technology Kristen Gallerneaux, in early 2021, a very exciting acquisition arrived at The Henry Ford: the Lillian F. Schwartz and Laurens R. Schwartz Collection. Lillian Schwartz is a groundbreaking and award-winning multimedia artist known for her experiments in film and video.

Lillian Schwartz was a long-term “resident advisor” at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey. There, she gained access to powerful computers and opportunities for collaboration with scientists and researchers (like Leon Harmon). Schwartz’s first film, Pixillation (1970), was commissioned by Bell Labs. It weaves together the aesthetics of coded textures with organic, hand-painted animation. The soundtrack was composed by Gershon Kingsley on a Moog synthesizer.

“Pixillation, 1970 / THF611033

Complementary to Lillian Schwartz’s legacy in experimental motion graphics is a large collection of two-dimensional and three-dimensional materials. Many of her drawings and prints reference the creative possibilities and expressive limitations of computer screen pixels.

“Abstract #8” by Lillian F. Schwartz, 1969 / THF188551

With this acquisition, we also received a selection of equipment used by Lillian Schwartz to create her artwork. The equipment spans from analog film editing devices into digital era devices—including one of the last home computers she used to create video and still images.

Editing equipment used by Lillian Schwartz. / Image courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

Altogether, the Schwartz collection includes over 5,000 objects documenting her expansive and inquisitive mindset: films, videos, prints, paintings, sculptures, posters, and personal papers. You can find more of Lillian Schwartz’s work by checking out recently digitized pieces here, and dig deeper into her story here.

Katherine White and Kristen Gallerneaux worked together this year to acquire several key examples of LGBTQ+ graphic design and material culture. The collection, which is currently being digitized, includes:

Illustrations by Howard Cruse, an underground comix artist…

Illustration created by Howard Cruse. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

A flier from the High Tech Gays, a nonpartisan social club founded in Silicon Valley in 1983 to support LGBTQ+ people seeking fair treatment in the workplace, as LGBTQ+ people were often denied security clearance to work in military and tech industry positions...

High Tech Gays flier. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

An AIDSGATE poster, created by the Silence = Death Collective for a 1987 protest at the White House, designed to bring attention to President Ronald Reagan’s refusal to publicly acknowledge the AIDS crisis...

“AIDSGATE” Poster, 1987. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

A number of mid-1960s newspapers—typically distributed in gay bars—that rallied the LGBTQ+ community, shared information, and united people under the cause...

“Citizens News.” / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

A group of fliers created by the Mattachine Society in the wake of the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, which paints a portrait of the fraught months that followed...

Flier created by the Mattachine Society. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

And a leather Muir cap of the type commonly worn by members of post–World War II biker clubs, which provided freedom and mobility for gay men when persecution and the threat of police raids were ever-present at established gay locales. Its many pins and buttons feature gay biker gang culture of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Leather cap with pins. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

Another acquisition that further diversifies our collection is the “Nude is Not a Color” quilt, recently acquired by Curator of Domestic Life Jeanine Head Miller. This striking quilt was created in 2017 by a worldwide community of women who gathered virtually to take a stand against racial bias.

“Nude is Not a Color” Quilt, Made by Hillary Goodwin, Rachael Door, and Contributors from around the World, 2017. / THF185986

Fashion and cosmetics companies have long used the term “nude” for products made in a pale beige—reflecting lighter skin tones and marginalizing people of color. After one fashion company repeatedly dismissed a customer’s concerns, a community of quilters used their talents and voices to produce a quilt to oppose this racial bias. Through Instagram, quilters were asked to create a shirt block in whatever color fabric they felt best represented their skin tone, or that of their loved ones.

Shirt blocks on the “Nude is Not a Color” quilt. / THF185986, detail

Quilters responded from around the United States and around the world, including Canada, Brazil, the United Kingdom, Spain, the Netherlands, and Australia. These quilt makers made a difference, as via social media the quilt made more people aware of the company’s bias. They in turn lent their voices, demanding change—and the brand eventually altered the name of the garment collection.

Jeanine Head Miller has also expanded our quilt collection with the addition of over 100 crib quilts and doll quilts, carefully gathered by Paul Pilgrim and Gerald Roy over a period of forty years. These quilts greatly strengthen several categories of our quilt collection, represent a range of quilting traditions, and reflect fabric designs and usage—all while taking up less storage space than full-sized quilts.

A few of the crib quilts acquired from Paul Pilgrim and Gerald Roy. / THF187113, THF187127, THF187075, THF187187, THF187251, THF187197

During 2021, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment Debra Reid has been developing a collection documenting the Civilian Conservation Corps, a New Deal program that employed around three million young men. This year, we acquired the Northlander newsletter (a publication of Fort Brady Civilian Conservation Corps District in Michigan), a sweetheart pillow from a camp working on range land regeneration in Oregon, and a pennant from a camp working in soil conservation in Minnesota’s Superior National Forest.

Recent Civilian Conservation Corps acquisitions. / THF624987, THF188543, THF188542

We also acquired a partial Civilian Conservation Corps table service made by the Crooksville China Company in Ohio. This acquisition is another example of curatorial collaboration, this time between Debra Reid and Curator of Decorative Arts Charles Sable. These pieces, along with the other Civilian Conservation Corps material collected, will help tell less well-documented aspects of the Civilian Conservation Corps story.

Civilian Conservation Corps Dinner Plate, 1933–1942. / THF189100

If you’ve been to Greenfield Village lately, you’ve probably noticed a new addition going in—the reconstructed Vegetable Building from Detroit’s Central Market. While we acquired the building from the City of Detroit in 2003, in 2021, Debra Reid has been working to acquire material to document its life prior to its arrival at The Henry Ford. As part of that work, we recently added photos to our collection that show it in service as a horse stable at Belle Isle, after its relocation there in 1894.

“Seventy Glimpses of Detroit” souvenir book, circa 1900, page 20. While this book has been in our collections for nearly a century, it helps illustrate changes in the Vegetable Building structure over time. / THF139104

Riding Stable at the Eastern End of Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan, October 27, 1963. / THF626103

Horse Stable on Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan, July 27, 1978. / THF626107

This year, Debra Reid also secured a photo of Dorothy Nickerson, who worked with the Munsell Color Company from 1921 to 1926, and later as a Color Specialist at the United States Department of Agriculture. Research into this new acquisition—besides leading to new ideas for future collecting—brought new attention (and digitization) to a 1990 acquisition: A.H. Munsell’s second edition of A Color Notation.

Dorothy Nickerson of Boston Named United States Department of Agriculture Color Specialist, March 30, 1927. / THF626448

All of this is just a small part of the collecting that happens at The Henry Ford. Whether they expand on stories we already tell, or open the door to new possibilities, acquisitions like these play a major role in the institution’s work. We look forward to seeing what additions to our collection the future might have in store!

Compiled by Curatorial Assistant Rachel Yerke from tweets originally written by Associate Curators, Digital Content, Saige Jedele and Katherine White, and Curators Kristen Gallerneaux, Jeanine Head Miller, and Debra A. Reid for a curator chat on Twitter.

quilts, technology, computers, Herman Miller, posters, women's history, design, toys and games, #THFCuratorChat, by Debra A. Reid, by Jeanine Head Miller, by Kristen Gallerneaux, by Katherine White, by Saige Jedele, by Rachel Yerke, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Healing in Music: Lavender Suarez Sound Healing

Lavender Suarez. / Photo by Jenn Morse

Lavender Suarez has made music as an experimental improviser for over a dozen years as C. Lavender and studied the philosophy of “deep listening” with composer Pauline Oliveros, which helped her understand the greater impact of sound in our daily lives. But it was seeing fellow artists and friends experience burnout from touring and stress that inspired her to launch her own sound healing practice in 2014.

“Many artists are uninsured, and I wanted to help them recognize the importance of acknowledging and tending to their health,” she said. “It felt like a natural progression to go into sound healing after many years of being a musician and studying psychology and art therapy in college.”

Suarez defines sound healing as “the therapeutic application of sound frequencies to the body and mind of a person with the intention of bringing them into a state of harmony and health.” Suarez received her certification as a sound healer from Jonathan Goldman, the leader of the Sound Healers Association. She recently published the book Transcendent Waves: How Listening Shapes Our Creative Lives (2020, Anthology Editions), which showcases how listening can help us tap into our creative practices. She also has presented sound healing workshops at institutions like New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and Washington, D.C.’s Hirshhorn Museum.

Continue Reading

healthcare, by Mike Rubin, The Henry Ford Magazine, women's history, music

Brain Food Barrier Breakers: Hamline University’s Feed Your Brain

Feed Your Brain free food pop-ups on campus at Hamline University are making healthier pantry and produce options available to hungry college students. Hamline students pictured, from left: Maggie Bruns, Feed Your Brain co-founder Emma Kiley, Maddie Guyott, Feed Your Brain co-founder An Garagiola-Bernier, and Najma Omar. / Photo courtesy Andy King

On October 26, 2017, students of Twin Cities–based Hamline University left work and class to flock to a few benches in a campus parking lot where more than 2,000 pounds of nonperishable food items were stacked. “We ran out in 30 minutes,” recalled An Garagiola-Bernier. A sophomore at the liberal arts school at the time, she organized the donation event, called Feed Your Brain, with fellow students Elise Hanson and Emma Kiley.

Even if the administration couldn’t see it, these three became acutely aware of food insecurity at Hamline after a sit-in over immigration laws earlier that year. “Students posted about immigration laws being changed, and some testified to experiencing so much hunger it was affecting their ability to learn,” said Garagiola-Bernier.

Photo courtesy Hamline University

The three friends wanted to dig deeper. They sent a survey to all undergrads to assess how food insecurity was affecting them, and included questions that addressed sourcing culturally appropriate food and healthy options for those with allergies or chronic conditions. “They were questions nobody was asking but students were really concerned about,” said Garagiola-Bernier.

Of the nearly 360 students who responded, 76% admitted to having trouble accessing food, and findings revealed heavier insecurity among Muslim, Hispanic, trans, and gay/lesbian students.

“We wanted to make the administration, and even the general public, aware that food insecurity is a profound indicator of poverty on college campuses,” said Garagiola-Bernier. “And if someone is food insecure, they’re also likely housing insecure or experiencing trouble with utilities or health care services.”

The findings contradicted Hamline’s reputation, and that of private college campuses in general, as places of privilege where food insecurity is an unexpected issue. “College students fall into a type of policy gap where they’re considered dependents of their parents. However, we know they’re living in financially independent situations,” said Garagiola-Bernier.

The first free food pop-up more than proved that, and a second one was held a month later. Feed Your Brain pop-ups continued monthly over the next two academic years (some intentionally set up in front of administration offices), and the founders continued to research food justice and work with faculty to help find a home for a food pantry.

Photo by Sabrina Merritt / The Oracle

“It was relentless advocacy and action first, and then asking for forgiveness later if we broke the rules,” said Garagiola-Bernier.

It was important for the pop-ups to offer students access to nonperishable, non-commodity foods and fresh produce. Not only do all three founders suffer from dietary health issues, but Garagiola-Bernier, a descendent of the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa, has seen the effects of unhealthy foods. “Being a Native woman, food sovereignty is a big issue,” she said. “Being able to choose what goes into your body and the repercussions of that, whether good or bad, and not just have commodity foods switched on you is vital. I’ve seen how having access only to unhealthy foods leads to extreme health conditions.”

In 2019, Feed Your Brain found a permanent home with the help of Kiley, who became the first campus food access AmeriCorps VISTA (Volunteer in Service to America), and the organization started hosting dinners and discussions on topics like the stigma of food insecurity. “It was a space where students could have meaningful conversations around topics that are hard to talk about,” said Kiley, who has since graduated and passed the reins of VISTA on to fellow student Sophia Brown.

Photo courtesy Hamline University

This year’s survey solidified the importance of those conversations as a 15% increase in food and financial insecurity was seen among students since COVID-19 hit.

“When we started, food was the easiest entry point into this work. But at its core, it’s always been more about justice and reparations, and we used food to have those conversations,” said Kiley. “There’s a high percentage of students that are food insecure, but it’s about more than that. We have to change the way we think about distributing food so it’s more about caring for your neighbor and less about feeling bad for people or stigmatizing experiences.”

Liz Grossman is a Chicago-based writer, editor, and storyteller, and is managing editor of Plate magazine. This post was adapted from an article first published in the January–May 2021 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

women's history, COVID 19 impact, food insecurity, The Henry Ford Magazine, by Liz Grossman, food

New Acquisition: The Lillian F. Schwartz Collection

Lillian Schwartz working with a joystick interface at Bell Laboratories. Photo by Gerard Holzmann. / THF149836

In early 2021, The Henry Ford secured a very exciting donation: the Lillian F. Schwartz & Laurens R. Schwartz Collection. This material—which came to us through the generosity of the Schwartz family—spans from early childhood to late career and includes thousands of objects that document Lillian Schwartz’s expansive and inquisitive mindset: films and videos, two-dimensional artwork and sculptures, personal papers, computer hardware, and film editing equipment.

The late 1960s in California were a heady time in computing history. Massively influential technologies that are now part of our everyday lives were being invented or improved upon: home computers, the graphical user interface, the computer mouse, and ARPAnet. Meanwhile, on the opposite side of the country in New Jersey, the artist Lillian Schwartz was about to walk through the doors of revered technology incubator Bell Telephone Laboratories. Schwartz had recently met Bell Labs perceptual researcher Leon Harmon at the opening for the Museum of Modern Art’s group exhibition “The Machine at the End of the Mechanical Age.” Harmon and Schwartz each had work in the exhibit, and the pair struck up a conversation that led to an invitation for Lillian to visit the Labs.

A poster for the Museum of Modern Art exhibit that led to Schwartz and Leon Harmon’s friendship (top) and a portrait of Harmon painted by Schwartz (bottom). / THF188555, THF188581

This fateful meeting led to Schwartz’s decades-long tenure as a “resident visitor” at Bell Labs, where she was exposed to powerful equipment like the IBM 7090 mainframe computer and Stromberg Carlson SC-4020 microfilm plotter. Allowing artists access to this high-end research and development facility upended conventions, creating an environment that was fruitful for cross-disciplinary collaboration between the sciences, humanities, and arts. From 1968 until the early 2000s, Schwartz paid regular visits to the Labs, where she developed groundbreaking computer films and videos, and an impressive array of multimedia artworks.

Continue Reading

women's history, making, technology, computers, The Henry Ford Magazine, by Kristen Gallerneaux, art