The Automobile and Women’s Suffrage

In the years following the introduction of the automobile, women had few chances to challenge prevailing, gendered beliefs about their place behind the wheel. But where limited opportunities did exist, women seized them. They competed in organized races and reliability tours, volunteered for motor service during World War I, and drove to rally support for women’s suffrage.

|

|

|

Along with competitive driving and volunteering for motor service during WWI, driving in support of women’s suffrage was one of few early opportunities for women to publicly demonstrate proficiency behind the wheel. Left to Right: Joan Newton Cuneo, lone female participant in the first Glidden Tour (1905); Alice Huyler Ramsey, second from left, first woman to drive across the US (1909); and ambulance drivers for the Red Cross (1918). THF101655/THF200502/Detail, THF270207

Concerted efforts to secure voting rights for American women had been ongoing since the mid-1800s. There had been some success—a handful of Western states had adopted full suffrage by 1910—but activists were eager to expand their reach and reinvigorate the aging movement. Some organizers turned to the automobile as a new strategy for garnering broader support for their cause. Before long, the automobile had become both a symbol of freedom for American women and an important tool in the fight for women’s suffrage.

Gertrude Foster Brown behind the wheel of the automobile she used to campaign for women’s suffrage. Detail, THF610069

The first major effort, a series of statewide automobile tours organized by the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association in the summer of 1910, marked a new path forward in the pro-suffrage campaign. Suffragists formed fifteen auto parties that spread out across the state, distributing literature and hosting open air meetings with speeches and songs promoting votes for women. Organizers were encouraged to find supporters in areas the movement hadn’t yet reached, and when women in Illinois gained presidential suffrage in 1913, many credited the automobile with helping them to victory. According to historian Virginia Scharff (whose book, Taking the Wheel: Women and the Coming of the Motor Age, is an invaluable resource on this topic), “the motorcar provided a technological solution to the problem of cross-country campaigning.” As suffragists embraced the practicality and convenience of the automobile, similar tours followed in states from California to Connecticut.

|  |

Outfitting automobiles with decorations amplified suffragists’ message and lent visibility to their cause. THF172667/THF8417

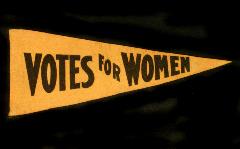

More than a means of transportation, the automobile became a mobile podium and billboard, drawing attention to the cause of women’s suffrage. Activists delivered speeches from motorcars, often draped with banners and other signage, which elevated them above the crowds and amplified their message. Suffragists organized automobile processions to attract favorable press and rally support. To boost visibility, participating vehicles could be outfitted with flowers, flags, and special accessories like hood ornaments. At a time when a woman behind the wheel could be enough to draw attention, organizers took full advantage of the automobile, creating a powerful new symbol of their cause.

|

|

As a national effort to secure votes for women grew into the 1910s, automobiles became the centerpieces of dramatic, large-scale demonstrations that captivated American attention. For example, in 1913, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) sent representatives across the country to collect signatures on petitions for a constitutional suffrage amendment. They delivered the signed petitions to Congress that summer via an impressive convoy of motorcars. Two years later, the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage organized a cross-country “suffrage envoy.” A team of women carried a hefty suffrage petition through parades and rallies, collecting signatures as they drove from San Francisco to Washington, D.C., where they joined a suffrage parade to the Capitol. In 1916, two women (again sponsored by NAWSA) set out in a yellow Saxon automobile dubbed the “Golden Flyer” to deliver speeches, distribute literature, and promote votes for women in cities across the country. Over the five-month tour, they covered more than 10,000 miles. This pageantry didn’t bring about equal suffrage on its own, but national tours captured public attention and may well have helped tip the scales in favor of the cause while cementing the automobile as an emblem of women’s suffrage.

|

|

The automobile’s significant role in the women’s suffrage movement wasn't a certainty from the start. At first, not all suffragists supported a nontraditional tactic—especially one that placed women in a position some viewed as unseemly. Compounding the argument were issues of class and privilege. Certain groups were often excluded from visible roles in the fight for women’s suffrage (see this project to learn about racial inequality within the movement), and the use of automobiles was no exception. In the early years, motorcars were expensive machines that were out of reach for most of the working-class activists, who were just as invested in the movement as wealthier suffragists with ready access to cars. Even though the automobile shed some of its aristocratic image as production methods improved and prices fell in the 1910s, motorcars lent the suffrage movement a stubborn upper-class association that organizers continually worked to deflect. In the end, suffragists agreed that the convenience and visibility automobiles promised warranted their place in the movement.

In July 1919, Motor magazine described “how the motor vehicle has aided in the long fight for suffrage now happily ending.” THF610068

In 1920, suffragists celebrated the formal approval of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which finally granted American women the right to vote. Automobiles continued to play an important and increasing role in helping to register new voters and get them to the polls, but inequalities between men and women remained—both in politics and behind the wheel. In the years that followed, activists continued to leverage new technologies in pursuit of equality. A century later, what technological solutions are propelling today’s campaigns for political and social change?

Saige Jedele is Associate Curator, Digital Content at The Henry Ford.

1910s, 20th century, women's history, voting, cars, by Saige Jedele

Facebook Comments