When Art and Activism Merge

“The artist's role is that of the soldier of the revolution.” -Diego Rivera

How does one interpret art? How does one view activism or protest? These concepts have merged for centuries to convey a message and drive change. “Activist Art,” as defined by the Tate Museum in London, is “a term used to describe art grounded in the act of ‘doing’ and addresses political or social issues.” It is a tool for change, a powerful medium that also challenges and disrupts them, stimulating thought and pushing boundaries. It is innovative, boundary-pushing, and, above all, a force for progress, empowering us with the hope that change is possible.

Throughout history, we can trace the influence of art on activism and protest. Both concepts have been intertwined since the birth of the United States. Consider the Boston Tea Party in 1773. This iconic and performative event was an act of protest aimed at making a point, immediately sparking illustrations in local newspapers. Colonists used images like this to advance their cause of independence and freedom, creating a rich historical tapestry that we can still learn from today, connecting us to our past and its influence on the present.

Even earlier, the revolutionary cause and the Boston massacre provide powerful examples of art's influence. This event, depicted in newspapers across the colonies, played a crucial role in fueling the desire for independence—leading to the Boston Tea Party, other smaller rebellions, and eventually to the American Revolution. This is a compelling example of how images can play a pivotal role in shifting a narrative and shaping history, enlightening us about the power of art in social and political change.

The Bloody Massacre Perpetrated in King Street, Boston, on March 5, 1770, from the collections of the Henry Ford / THF130817

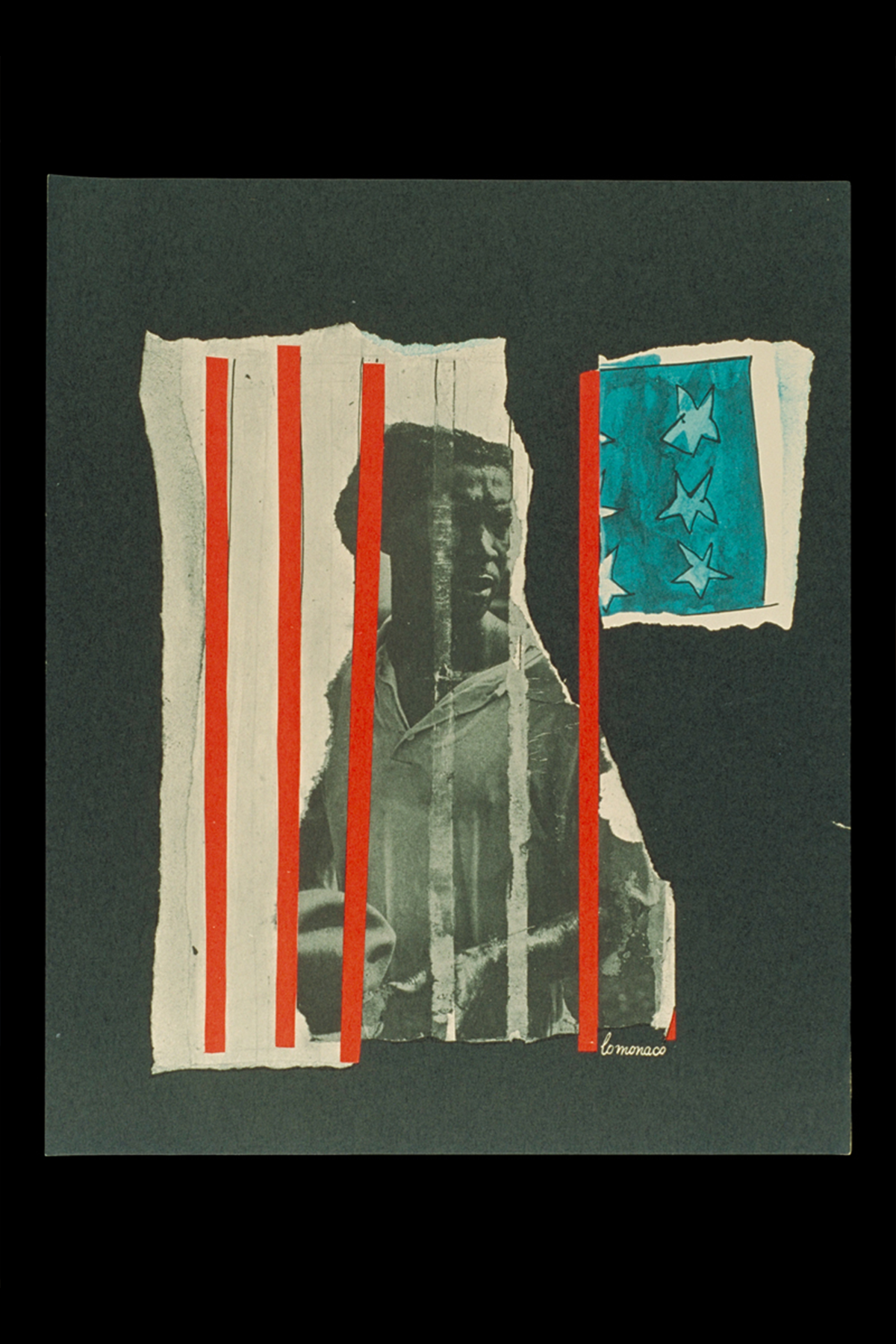

A jail can only hold a man’s body - his mind and heart remain free, by Lo Monaco’s “We Shall Overcome” 1963 print portfolio, from the collections of The Henry Ford / THF93154

On August 28, 1963, the March for Freedom and Jobs took place in Washington, D.C. The print above comes from a portfolio containing five images created by the graphic artist, Lo Monaco. The portfolio was created to hold memories of the march that day, serving as a message and reminder of the work needed to address issues of bigotry and racism in the United States.

Diné artist Demian DinéYazhi’ made the print below, my ancestors will not let me forget this, as a statement about the original 13 colonies and how life changed drastically for the Indigenous people after the American Revolution. They created it in the summer of 2020 after the murder of George Floyd, when there was much racial tension in the United States and questions related to equality and human rights. This print was inspired by an earlier piece DinéYazhi’ created for the Eiteljorg Museum in 2019. As the artist is Indigenous, this piece speaks to colonization and the broader context; it addresses how we think about the United States and, in this case, what the flag means to Indigenous people.. It is proactive, bold, activism, and art, inspiring us to continue the fight for equality and human rights.

my ancestors will not let me forget this by Demian DinéYazhi’ (Diné), from the collections of The Henry Ford / THF718200

Collecting in the moment—known as rapid response collecting--allows curators to gather significant items in the moment, as historic and social events are happening. The Henry Ford actively engages in this type of collecting, as do other large cultural institutions. Some of this rapid response collecting happened during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, the COVID-19 pandemic, and presidential election seasons. Rapid collecting can be difficult—it can be messy, and it happens fast. However, as we are a cultural institution, it benefits our collections to gather important historical moments as they happen.

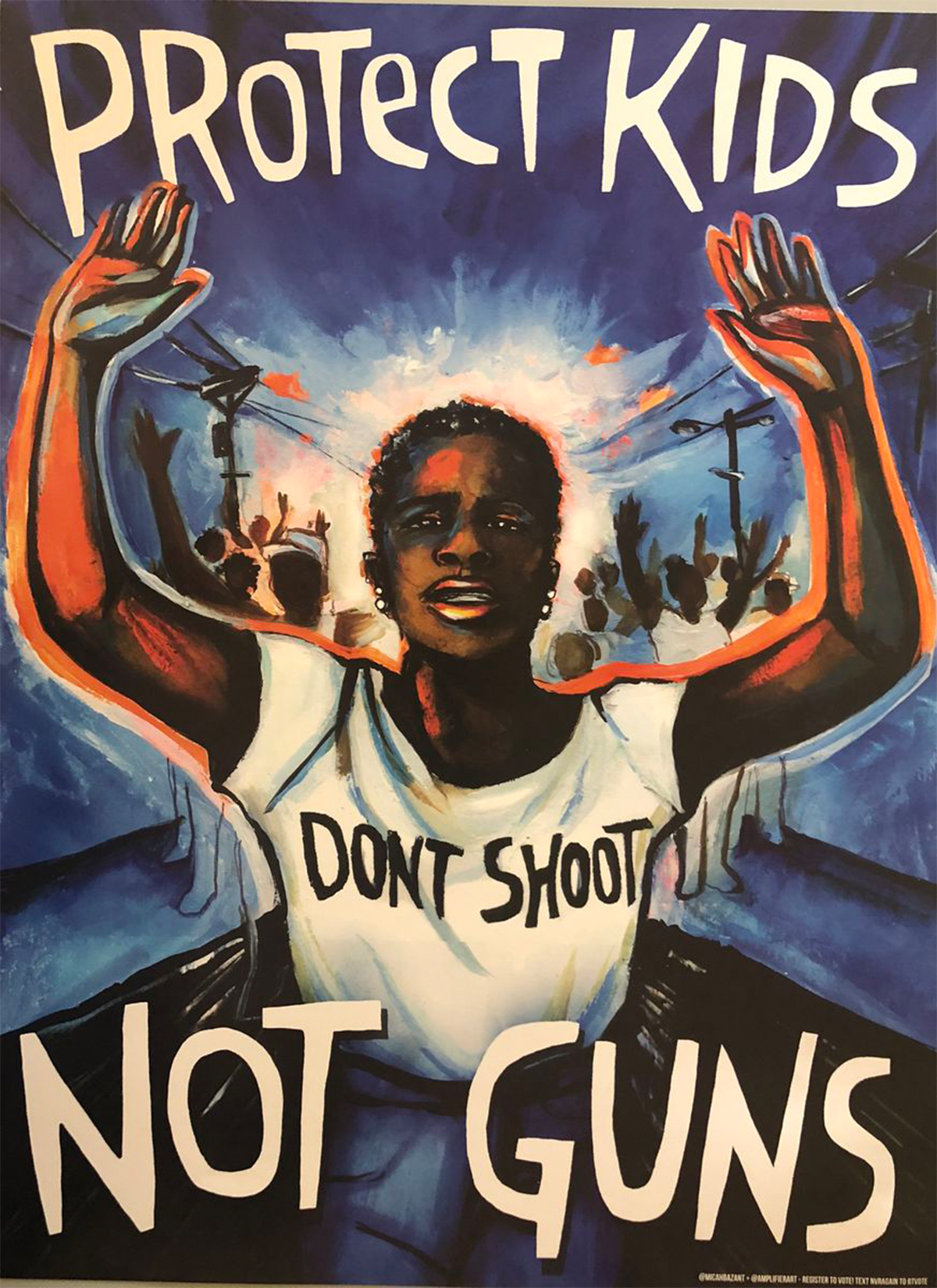

On February 14, 2018, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School became the site of a mass school shooting.Since the school is located in Parkland, Florida, the incident is often referred to as the Parkland shooting. Seventeen students and staff lost their lives that day. Since the shooting at Columbine High School in 1999, the number of school shootings in the United States has steadily increased. After the Parkland shooting, the students united and organized and created March for Our Lives. On March 24, 2018, just a short five weeks after the shooting, March for Our Lives held the largest student-led protest in US history in Washington, DC, with 1.2 to 2 million people in attendance and more participating around the world. Partnering with the Amplifier Art Foundation, artist Micah Bazant created this poster, carried at the marches by protesters.

Protect Kids Not Guns by Micah Bazant, from the collections of the Henry Ford / 2018.88.5

Activism and art each make us think. Combining them creates change and can even start revolutions. In addition to the quote that started this post, Diego Rivera also said: "Great protests are great works of art.” Art as protest, and protest as art—the two concepts will hold hands forever.

Heather Bruegl (Oneida/Stockbridge-Munsee) is the curator of political and civic engagement at The Henry Ford.

Facebook Comments