Curating & Preserving

The 1897 Baldwin Steam Locomotive

As one of the most respected transportation museums in the world, showcasing the railroad industry’s greatest accomplishments is a hallmark of what we do at the Henry Ford. But we know that when we return artifacts to operation, we have a responsibility to do so as accurately and meticulously as possible. When it came to restoring the Baldwin locomotive, we had to secure the necessary skills and facilities to tackle this challenging job. Fortunately, we were able to team up with Railroad Operations—a group that maintains our operating steam locomotives, rolling stock, tracks and signal systems.

Securing Mechanics and Tools for the Job

Railroad Operations personnel maintain our equipment at Greenfield Village’s Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Roundhouse. Built in 2000 to closely replicate the 1880s DT&M facility in Marshall, Michigan, this facility is well equipped with the necessary tools and machines to serve the Village’s railroad operations.

Maintaining a railroad is far more difficult and requires more specialized equipment than maintaining an automobile. Since there is no “AutoZone” for steam locomotives, anything that needed to be replaced on the Baldwin had to be fabricated onsite, requiring extensive machinery and skill. Additionally, since casting replacements is exacting work, extensive design and drafting skills were often necessary.

Disassembly

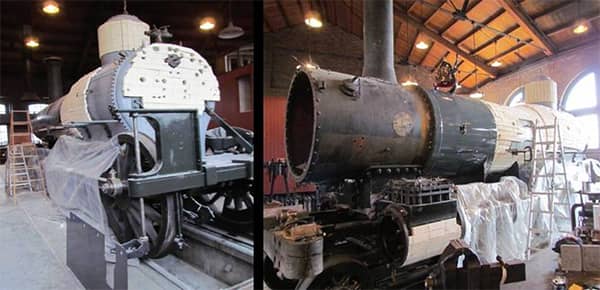

The Baldwin’s restoration began in 2007 with disassembly. Taking apart a locomotive is a time consuming and physically demanding process. Before the major disassembly could begin, many tubes, valves and ancillary systems had to be removed. These parts had not been touched for over 80 years, making this project especially challenging.

In September of 2007 the removal of the major components began with the separation of the cab from the chassis (pictured below). In early December the boiler was removed so it could be worked on with unobstructed access to the areas that would need to be replaced (pictured below).

In early 2008, the process of removing sections of the boiler and firebox began, along with the removal of hardened scale from the boiler walls. Scale, a chalky deposit left by impurities in the water, damages the boiler over time. Work on the boiler continued through the year, with mechanics removing the sections that would be replaced and preparing the surfaces for installation of the new ones.

Tackling the Boiler

After the preparation phase, fabrication of the new boiler sections began. One of the most complicated and demanding sections was the rear tube sheet. This is the part that faces the firebox and holds the heat tubes in place so that the heat generated in the firebox can be drawn through the boiler to heat the water and create steam.

The first phase of the tube sheet forming began with the use of a McCabe flanging tool. This pneumatically powered machine, built in 1921, was a common tool in roundhouses of that period, and this machine can form flanges of sheet steel up to ¾ of an inch thick. The flanging tool saved a significant amount of work but was limited as it could not flange the tight radius needed for the top corners. Those portions of the tube sheet would require hand forming.

To facilitate the hand forming, a 1½ inch thick metal die had to be fabricated, and Railroad Operations lacked the time to complete this portion so they developed drawings to guide an outside company was tasked with the hand forming. The partially formed steel sheet was then rigidly attached to the die and the remaining forming was finished after the immediate area being formed was heated red hot by acetylene torches. The heated portion could then be formed by the use of special hammers, made of reinforced hard wood that would not dent the red hot steel. Dent marks would structurally weaken the metal and compromise the stability of the locomotive’s boiler. The upper corners of the sheet had to be cut at the centerline of the curve to form a smooth joint that could be welded with precision.

After the forming process was completed, the sheet was drilled to create holes for the heat tubes and stay bolts. Since the heat tubes were almost 12 ft. long and required a very close fit at each end to ensure sealing, locating and drilling the holes had to be accomplished with accuracy.

Work on the boiler continued into 2009 with fabrication of the firebox floor and door sheet. Throughout all this fabrication the parts had to be precisely measured to an accurate fit. Repairs like these are critical to a train’s safe operation. Boilers are closely regulated by the government and all welding has to be done by a boiler-certified welder. These welders ensure that the components sit flush and are perfectly aligned to create high-quality welds.

However, if you’ve made it this far, then you know that the welded elements of the boiler were only part of the story. The non-cylindrical parts, like the firebox and crown sheet, had to be held in position inside the boiler by a device called a stay bolt. Stay bolts are threaded rods that hold the firebox and crown sheet in position while water circulates around it. New stay bolts were sized and machined for each individual location by the roundhouse crew.

Once the stay bolts are installed (see below), the exposed ends are “upset” (like a rivet) so they are sealed and fixed into position. When the stay bolt is fabricated, it is drilled down its center (see below) so that if it cracks or breaks during service, a small trail of water or rust will appear on the head indicating an internal failure of the stay bolt.

A locomotive boiler like the one in the Baldwin has hundreds of these bolts that have to be individually machined to assure proper fit and sealing. Many of these would have to be replaced due to the new sections of the boiler.

Let the Painting Begin!

With the components of the boiler fastened, it was time to paint them with high temperature epoxy paint and install the insulation blocks. The calcium silicate insulator blocks (shown below) replaced the asbestos removed in 1997 and are necessary to help keep heat in the boiler and provide an insulated barrier to protect the “jacketing” —a layer that primarily serves to keep the insulation blocks in places, thus keeping heat inside the boiler and protecting train personnel.

Parallel to the work on the boiler was the restoration of the tender. This car, pulled immediately behind the locomotive, carries the coal and water needed to produce steam. A new frame was required to ensure that the Baldwin’s tender would hold up to daily use. Additionally, the original wooden frames were replaced by a stronger steel frame assembly, an option on the original factory builds.

The upper part of the tender was sand-blasted to bare metal and the 3,350 gallon water tank was tested for integrity. After the sandblasting was complete, the tender was painted “as delivered” green with the name “Detroit & Lima Northern” hand-painted on the side, along with the painted trim shown in the original Baldwin Locomotive Works photos.

Although the Baldwin’s “as built” information identified a specific color name, there were no color chips to determine the exact shade. For railroad purists, it is important to note that each Baldwin painter mixed his own paint; it is unlikely that any replicated color could be an exact match. The color we used was the result of significant research and was mixed by Chris Dewitt of the Nevada State Railroad Museum. A 1913 Baldwin in their collection had a small section that provided the only known “color chip” of the original paint. This sample was analyzed and the museum provided a chip from that analysis for our restoration.

On June 12, 2013, in a satisfying conclusion to the restoration process, the 1897 Baldwin went onto the Greenfield Village railroad tracks under its own power. The restoration of the locomotive was a difficult and labor-intensive undertaking, but it represents The Henry Ford’s commitment to historical accuracy and its position as one of the world’s leading transportation museums.