What If

When a former country store clerk from rural New York named George H. Corliss invented a revolutionary new steam engine in 1849, steam power finally overtook waterpower as a superior source of energy for American industry. No invention since [James] Watt’s time has so enhanced the efficiency of the steam engine. Dr. Asa Gray

The Spectacle of American Invention

On a chilly May morning in 1876, after waiting patiently under overcast skies outside Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park for the gates to open, tens of thousands of people streamed into the Centennial Exposition fairgrounds to see the latest displays of ingenuity from around the world. As the first official World’s Fair hosted in the United States, the event coincided with the hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Not surprisingly, it was choreographed to offer a particularly dramatic display of American confidence and modernity. Among the American exhibitors showcasing their latest inventions and ideas: Alexander Graham Bell demonstrated his newly patented telephone; Thomas Edison displayed an electric pen; and Eliphalet Remington unveiled a new commercial typewriter.

Portrait of George H. Corliss, circa 1880

Artifact

Photographic print

Creators

Object ID

P.188.540

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Ford Motor Company.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Portrait of George H. Corliss, circa 1880

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

At the time, nothing signaled technical sophistication and industrial might more than steampower. Which is why the unveiling of a double-cylinder steam engine featuring the world’s largest flywheel, measuring 30 feet in diameter and weighing 56 tons, was considered the greatest marvel at the event. The man who designed it—a former country store clerk named George H. Corliss—was more celebrated than any other inventor in attendance, including even Bell and Edison.

A Legendary Product Announcement

Like many staged events at the Centennial Exposition intended to inspire wonder and awe, including a 1,000-voice choir and 100-gun salute at the opening ceremonies, the moment the Corliss steam engine came to life was carefully planned. Corliss, much like Steve Jobs more than a century later, was the genius behind not only the new technology but orchestrating the public relations event. He ensured his steam engine, which took 10 months to build, was erected on a five-foot high platform inside one of the most magnificent pavilions (Machinery Hall covered 558,000 square feet or 14 acres, more than four times the size of St. Peter’s in Rome). The two-story Corliss steam engine towered above the other machines around it.

On opening day, Corliss invited the event’s most famous guests—President Ulysses S. Grant and a foreign diplomat beloved by Americans, Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro—to pull the twin levers to start the motors. Corliss had located the noisy boilers in an adjacent building, so when the 1,400-horsepower steam engine started up, spectators were astonished. All the machines in the immense hall began to run, powered by the Corliss engine through shafts that totaled more than a mile in length. And yet, unbelievably, the giant engine operated silently, as if by magic.

The display inspired almost mythical reverence for Corliss’s “Centennial Engine.” Editor of the Atlantic Monthly, William Dean Howells, praised the Corliss engine as “an athlete of steel and iron with not a superfluous ounce of metal on it.” Walt Whitman was awestruck by what he saw. In the words of another writer traveling with Whitman, Joquin Miller, the famous poet “sat looking at this colossal and mighty piece of machinery for half an hour in silence…contemplating the ponderous motions of the greatest machinery man has built.”

This was just the sort of fanfare Corliss had hoped for. “He clearly wanted to be a dominating presence at the exposition,” says Marc Greuther, Chief Curator at The Henry Ford. “But the paradox is that the engine that was deployed to inspire an almost godlike presence wasn’t really at the forefront of Corliss’s own capabilities.”

Powering the American Industrial Revolution

More than two decades before his spectacular machine became the talk of the Centennial Exposition, George Corliss was celebrated for his breakthrough in steam engine design. At the time, steam engines had been around for more than a century, beginning with British inventor Thomas Newcomen’s discovery of how to use steam pressure inside a cylinder to push down a piston. Designed around 1712, Newcomen’s was the world’s first steam engine, used to pump water out of a mine. Some 50 years later, Scottish inventor James Watt improved upon Newcomen’s invention by designing a separate condensing chamber, which prevented steam loss and allowed the engine to run continuously.

It took another 80 years before Corliss, in the late 1840s, discovered how to improve on Watt’s design by creating a steam engine that offered superior fuel consumption and smooth running speeds. The inventor, then in his early 30s, devised a unique system of four separate rocking valves (two for intake, two for exhaust) that permitted steam to quickly pressurize inside a cylinder, push down a piston and then be expelled before it cooled and condensed, conserving precious engine heat. He also designed an automatic variable cutoff valve, allowing the speed of the engine to be determined by the load placed on it. As historian Maury Klein noted in his book, The Power Makers, “The ‘automatic drop-cutoff’ controlled the amount of steam entering the cylinder far more efficiently than any existing type. The Corliss valve gear gradually became the standard among not only American but British engine manufacturers.”

Corliss’s more practical, reliable, and affordable steam engine enabled large numbers of American manufacturers to purchase a steam engine to power their mills and factories, which freed them from their previous dependence on water for power. This, in turn, changed where American industry grew and thrived. With power no longer tied to water sources, business owners could locate factories wherever they saw the greatest opportunity, whether that was a landlocked city with large labor forces or a rural location with rich natural resources.

In particular, the Corliss engine gave rise to giant textile centers, such as Fall River, in Massachusetts. The energy needed to drive the vast numbers of machines used in textile mills was considerable but the delicacy of the threads and fabrics produced by textile machinery demanded that the power source be very responsive. The patented Corliss valve gear allowed the engine to maintain the precise speed needed to avoid thread breakage while simultaneously responding to varying loads as different machines were brought in or out of operation.

Corliss’s achievements led to the success of his own business, The Corliss Steam Engine Company, which he started in 1856 in Providence, Rhode Island, with his older brother. They also earned him international recognition. At the Paris Exposition of 1867 his steam engine won the gold medal. Three years later, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences awarded him the Rumford Prize—one of the oldest scientific prizes in the U.S., in recognition of achievements by scientists in the fields of heat and light. During that ceremony, Dr. Asa Gray, a leading natural scientist of the era, made his famous declaration that "no invention since Watt’s time has so enhanced the efficiency of steam engine."

No invention since [James] Watt’s time has so enhanced the efficiency of the steam engine.

Dr. Asa Gray

Leading natural scientist of the era

Dr. Asa Gray

Leading natural scientist of the era

Honoring the Genius behind the Ingenuity

The international honors helped to elevate Corliss’s American reputation as one of the world’s foremost builders of steam engines. It was a reputation that, closer to home, was slower to develop, in part because he had not received traditional academic training. Born the son of a physician in Easton, New York, Corliss left school at age 14 to work as a shopkeeper and then, after briefly returning to school, eventually opened his own country general store in 1838, when he was 21. When customers complained about poorly stitched shoes, Corliss was determined to solve this problem himself. With just a basic understanding of tools, he designed a machine to stitch leather and received a patent for a machine for sewing boots in 1842, the first of many patents that would eventually include boilers, machine tools, and steam appliances.

Two years later, at the age of 27, Corliss moved to Providence, Rhode Island, and began working as a draftsman for a machine and engine building firm, where he would ultimately make his dramatic improvements to the steam engine. While he was a dedicated engineer, he claimed to never read technical journals nor work beyond regular working hours. He was litigious, continually fighting to defend his patents and thwart their infringement and yet was willing to incur a financial loss by delaying delivery of a boiler when it was discovered that a robin had built a nest in a wheel of the only vehicle large enough to make the delivery—the customer had to wait for the bird’s brood to leave the nest.

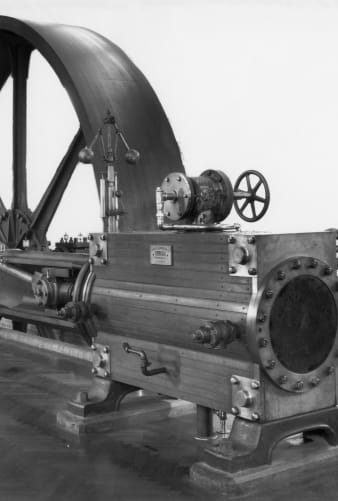

The 1859 Corliss engine in the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation™—while considerably smaller than the Centennial Engine, producing only 300 horsepower—served more than 60 years as the central source of power for some dozen independent workshops in Providence. Owned by the Washington Real Estate Company, and donated anonymously to the museum in 1926, it is powerful and massively built but incorporates many graceful and apparently delicate elements. It is the only engine built by the Corliss Steam Engine Company during George Corliss’s lifetime to have survived.

Corliss Steam Engine, 1859

Artifact

Steam engine (Engine)

Date Made

1859

Summary

George Corliss was one of the United States' most highly regarded steam engine designers. His valve innovations made his engines particularly important to the textile industry--where a combination of high power output and quick response to changes in load were greatly valued. He designed many of the machines used to manufacture his engines and was a pioneer in standardized manufacturing techniques.

Place of Creation

Object ID

29.403.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Corliss Steam Engine, 1859

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

This 1859 machine, like many of Corliss’s steam engines, remained in service far longer than his famous Centennial Engine. That machine was ultimately sold to American industrialist George Pullman, who, according to the Smithsonian Institution, had it shipped to Chicago in 35 boxcars and used it to power the machines that manufactured his sleeping cars. But after only 30 years of service, the historic steam engine “was sold as junk for $8 a ton.”

That such a machine was soon forgotten is a reminder that the unveiling at the Centennial Exposition marked a short-lived pinnacle in achievement for stationary steam power. The Industrial Revolution was well underway, fueled in good measure by Corliss’s steam engine innnovations decades earlier. And already a new disruptive technology—a power source called the internal combustion engine—was stirring in the minds of great engineers. Ten years after the Centennial Exposition, a German inventor named Karl Friedrich Benz registered a patent on an automobile powered by a gasoline-fueled internal combustion engine, marking a moment when the Age of Steam was giving way to the Age of the Automobile.

“Corliss is a useful reminder to us that anything that’s highly innovative at any given point is the result of a process that will result in that innovation also becoming obsolete,” says Greuther. “He was absolutely incredible in his field and he continued to refine, but eventually he was swept aside. That’s a fascinating lesson: Innovation as a process should be our perennial focus. Innovations individually all have the seeds of their demise hardwired into what they are. I remind myself of that all the time. The most modern thing you can think of will, at some point, be the most ancient thing in someone else’s eyes.”

Browse Collections

Engraving, "The Great Corliss Engine in Machinery Hall," 1876

Artifact

Print (Visual work)

Creators

Place of Creation

Object ID

34.769.5

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Location

Not on exhibit to the public.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Engraving, "The Great Corliss Engine in Machinery Hall," 1876

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Corliss Steam Engine, 1859

Artifact

Steam engine (Engine)

Date Made

1859

Summary

George Corliss was one of the United States' most highly regarded steam engine designers. His valve innovations made his engines particularly important to the textile industry--where a combination of high power output and quick response to changes in load were greatly valued. He designed many of the machines used to manufacture his engines and was a pioneer in standardized manufacturing techniques.

Place of Creation

Object ID

29.403.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Corliss Steam Engine, 1859

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Portrait of George H. Corliss, circa 1880

Artifact

Photographic print

Creators

Object ID

P.188.540

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Ford Motor Company.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Portrait of George H. Corliss, circa 1880

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Watt Canal Pumping Engine, 1796

Artifact

Steam engine (Engine)

Date Made

1796

Summary

Boulton and Watt built this engine for the Warwick and Birmingham Canal Navigation Company in 1796. It was used at the Bowyer Street pumping station in Birmingham, England, to pump water on the Bordesley Canal until 1854, when it was superseded by a more modern engine. The engine remained in the pumping station until coming to The Henry Ford in 1929.

Place of Creation

Keywords

Object ID

29.1531.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Watt Canal Pumping Engine, 1796

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Newcomen Engine, circa 1750

Artifact

Steam engine (Engine)

Date Made

circa 1750

Summary

This is the oldest known surviving steam engine in the world. Named for its inventor Thomas Newcomen, the engine converted chemical energy in the fuel into useful mechanical work. Its early history is not known, but it was used to pump water out of the Cannel mine in the Lancashire coalfields of England in about 1765. The engine was presented to Henry Ford in 1929.

Place of Creation

Keywords

United Kingdom, England, Greater Manchester, Ashton under Lyne

Object ID

29.1506.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Earl of Stamford Trustees.

Related Objects

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Newcomen Engine, circa 1750

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Group of Men in Front of Corliss Steam Engine, circa 1910

Artifact

Photographic print

Summary

American engineer George Henry Corliss patented the Corliss engine in 1849. Existing stationary steam engines were less efficient - and, therefore, more expensive - than those powered by water. Corliss's improved engine was highly efficient and enabled industries to develop anywhere. This photograph shows a group of men on a large Corliss steam engine around 1910.

Object ID

86.18.263.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Group of Men in Front of Corliss Steam Engine, circa 1910

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Discussion Questions

- What or who motivated George H. Corliss to innovate?

- What traits of an innovator did George H. Corliss illustrate?

- Which of these traits do you think was most important to his success as a steam engine innovator?

- Do you think you can be an innovator like George H. Corliss? Why or why not?

Fuel Your Enthusiasm

The Henry Ford aims to provide unique educational experiences based on authentic artifacts, stories and lives from America’s tradition of ingenuity, resourcefulness, and innovation. Connect to more great educational resources: