Posts Tagged 20th century

Black Entrepreneurs during the Jim Crow Era

Two Sisters Beauty Salon, 1945-50. THF240367

“Jim Crow” laws—first enacted in the 1880s by angry and resentful Southern whites against freed African Americans—separated blacks from whites in all aspects of daily life. Favoring whites and repressing blacks, these became an institutionalized form of inequality.

Jim Crow was a character first created for a minstrel-show act during the 1830s. The act—featuring a white actor wearing black makeup—was meant to demean and make fun of African Americans. Applied to the later set of laws and practices, the name had much the same effect. THF98689

In the Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states had the legal power to require segregation between blacks and whites. Jim Crow laws spread across the South virtually anywhere that the two races might come in contact. In the North and Midwest, segregation became equally entrenched through informal customs and practices. Many of these laws and practices lasted into the 1960s, until outlawed by the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Through separate (and inferior) public facilities like building entrances, elevators, cashier windows, and drinking fountains, African Americans were reminded everywhere of their second-class status. THF13419, THF13421

It took a great deal of courage, resilience, and strength of character for African Americans to maintain their self-respect and battle the daily humiliation of Jim Crow. The black church, self-help organizations, and men’s and women’s clubs offered refuge, support, and protection, while the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) provided potential legal assistance.

The NAACP, formed in 1909, emphasized fighting for racial equality through legal action rather than political protest or economic agitation. THF11647

Out of the demeaning environment of Jim Crow arose the opportunity for some African Americans to establish their own businesses. The more cut off that black communities became from white communities and the more that white businessmen refused to cater to black customers, the more possible it became for enterprising black entrepreneurs to create viable businesses of their own.

Most of these businesses were local, small-scale, and family-run. Many black entrepreneurs followed the tenets of Booker T. Washington, who had established the National Business League in 1900 to promote economic self-help. Washington advocated economic development as the best path to racial advancement and the means to eventually challenging the racial prejudice of Jim Crow. While Washington’s precepts would become increasingly out of step with the times, especially when the Civil Rights movement gained momentum, the support for his ideas among black entrepreneurs of the Jim Crow era is repeatedly evident in the naming of businesses after Washington.

The following images from the collections of The Henry Ford provide an intriguing window into the world of black enterprise and entrepreneurship during the Jim Crow era.

Barber Shops

Rodger Clark’s No. 1 Barber Shop, c. 1950. THF240383

Black barbers had long cut white customers’ hair as part of their traditional second-class status in service to white people. But, by the early 20th century, white patrons had begun to shift their business to white-owned shops. A new generation of black barbers proudly established shops within their own communities, catering to a growing black consumer market. They knew that their white counterparts would offer no competition, as they did not want the close contact with blacks that cutting hair demanded. Nor could white barbers offer black men the kind of haircut and shave that they themselves knew how to give.

The cost to enter the field was low but black barbers’ status was high. They generally attracted a regular customer base, akin to church preachers. Men congregated and felt comfortable in these shops, and conversation flowed freely, both about local goings-on and larger racial matters that concerned them all. Barber shops remained important spheres of influence during and after the Civil Rights era.

Beauty Parlors

The rise of black female beauty culture paralleled larger trends in society, especially the influence of mass media like movies and popular magazines. Several black female entrepreneurs spearheaded an emerging beauty culture industry—the most famous of these being Madam C. J. Walker. Some enterprising black women, initially trained as agents to sell special hair preparation and cosmetic products (so-called “beauty systems”), eventually opened their own beauty shops as permanent spaces to facilitate their work as “beauty culturists.” With the little capital needed to start their own businesses, they could free themselves from economic dependence on their husbands or on white employers. It was respectable work, considered doing their part for racial progress and the economic uplift of the black race.

Beauty parlors became places where black women could indulge in moments of pampering, self-indulgence, and relaxation while also letting off steam, gossiping, and speaking their minds. Increasingly, beauty parlors became vital public spaces that nurtured debate and activism among women within black communities.

Undertakers and Funeral Directors

Booker T. Washington was depicted on the front of this cardboard handheld fan for the Jacob Brothers Funeral Home, Indianapolis, Indiana, circa 1955. As advertised on the back, the funeral home promised air-conditioning and an organ in its chapels. THF224305

By the 1920s, funeral homes had emerged across the country as primary locations for carrying out the responsibilities of handling and burying the deceased. These first emerged in large towns and cities and gradually spread to rural regions. Funeral homes became a particularly lucrative avenue of entrepreneurship for blacks, which lacked white competition because of the close physical contact that was involved in this work. When African Americans were excluded from joining the National Funeral Directors Association, they organized their own independent organization in 1925.

People entrusted black undertakers and funeral directors in their local communities with the proper and responsible treatment of their deceased loved ones. These entrepreneurs offered an appropriate mixture of respect for traditional religious practices, modern American values, and the changing desires of local neighborhoods. Some black funeral homes flourished through aggressive marketing and modern amenities like spacious limousines.

Cafés, Taverns, and Liquor Stores

Dixie Liquor Store, St. Louis, Missouri, 1940s. THF240367

Saratoga Café and Sportsman Lounge, Chicago, Illinois, 1940s. THF240377

During the Jim Crow era, segregation may have been the law in the South but it was just as apparent in northern and midwestern cities. Restaurants, cafés, taverns, and liquor stores thrived in black neighborhoods, established by local businessmen and geared to local customers. These two stores—in St. Louis, Missouri and Chicago, Illinois—seem to have been extremely popular gathering places for both men and women.

Roadside Amenities

The Negro Motorist Green Book, 1949. THF 77183

It was one thing to frequent the businesses in your own neighborhood. But what happened when you took an out-of-town road trip? Where might you and your family inadvertently encounter hostility, be turned away, perhaps even risk your lives? Black postal worker Victor H. Green attempted to help black travelers combat this dilemma by creating The Negro Motorist Green Book. From 1936 to 1966, the Green Book offered a directory of safe places for African-American travelers. This included not only the expected roadside amenities of lodgings, service stations, and restaurants, but also listings of many of the classic businesses found in local neighborhoods—like barber shops, beauty parlors, liquor stores, and nightclubs. [For more on the Green Book, see this blog post.

A. G. Gaston Motel, 1954. THF 104701, 104700

One of the most difficult and risky aspects of cross-country travel for African Americans was the question of where to stay overnight. The Negro Motorist Green Book attempted to update its listings as often as possible, while word of mouth helped African Americans learn of safe places—who often drove miles out of their way to get to them. But the fact remained that the most extensive listings of hotels and motels were in northern metropolises with large populations of black Americans. In smaller towns, a tourist home or two might be listed—which meant staying in a room in someone’s house. Many towns lacked even a single listing.

In 1954, a new kind of black-owned lodging opened in Birmingham, Alabama, coinciding with a black Baptist convention in town. Billed “The Nation’s Newest and Finest Motel,” it was built, owned, and run by pioneering black entrepreneur Arthur George (A. G.) Gaston. Gaston also established several other businesses in Birmingham, including a bank, radio stations, the Booker T. Washington Insurance Company, a funeral home, and a construction firm.

Modeled after the groundbreaking Holiday Inns that had recently opened in Memphis, Tennessee, the A. G. Gaston Motel included 32 rooms, each with their own air-conditioning and telephone. Gaston remarked that opening this motel “means that many persons passing through our city will have a fine place to stay.” In 1963, the Gaston Motel became the epicenter of Birmingham’s Civil Rights protests and demonstrations.

Berry Gordy and Motown Records

This Smokey Robinson and the Miracles 45 rpm record was licensed to and issued nationally by Chess Records because Motown as yet lacked a national distribution network. THF170558

Berry Gordy Jr., founder of Motown Records in Detroit, Michigan, in 1959, created a business that successfully bridged the Jim Crow era and the post-Civil Rights Act era. He accomplished this by accurately predicting the coming of an integrated market of consumers for black popular music.

In 1922, Gordy’s father, Berry Sr., moved his family to Detroit from Georgia—an area steeped in Jim Crow laws and practices—because he faced hostility and potential violence from local whites when his food distribution business proved too successful. Berry Sr. established the Booker T. Washington Grocery Store in the black working-class neighborhood of Detroit, which soon also became highly successful. All the while, he encouraged his children to be industrious and establish their own business ventures.

Inspired by the legendary boxer Joe Louis, Berry Jr. first dreamed of becoming a famous boxer but he eventually gravitated to his other interest—music. From record store owner to songwriter to multi-million-dollar record producer and distributor, Gordy used his business savvy to redefine black music coming out of Detroit as popular music that both blacks and whites would want to hear and buy. Throughout the monumental success of his career, Gordy claimed that he had continually upheld his family’s business ethic and the self-help ideals of Booker T. Washington.

The Jim Crow Era provided the impetus for a number of black businesses to grow and flourish, instilling a sense of pride within black communities, serving as symbols of racial progress, and promising safe places to do business and socialize. The conversation and ideas that flowed freely in black business establishments also helped raise consciousness and establish a sense of solidarity within black neighborhoods. When the Civil Rights movement gained momentum—offering an end to the indignities and disenfranchisement of Jim Crow—many black entrepreneurs did what they could to support the movement. After the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964, and segregation was declared illegal, black entrepreneurs could take pride in the role they had played in the Civil Rights movement despite the fact that the future viability of their segregated businesses were now in jeopardy.

To read more on these topics, check out these helpful books:

- Cutting Across the Color Line: Black Barbers and Barber Shops in America, by Quincy T. Mills (2013)

- Style and Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women, 1920-75, by Susannah Walker (2007)

- Pageants, Parlors, and Pretty Women: Race and Beauty in the 20th Century South,(2016)

- Dancing in the Street: Motown and the Cultural Politics of Detroit, by Suzanne E. Smith (1999)

Donna R. Braden is the Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 19th century, entrepreneurship, by Donna R. Braden, African American history

Motown’s Contribution to the Civil Rights Movement

Motown Record Album, “The Great March to Freedom: Rev. Martin Luther King Speaks, June 23, 1963.” THF31935

Detroit’s Walk to Freedom, held on June 23, 1963, helped move the southern Civil Rights struggle to a new focus on the urban North. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. later called this march “one of the most wonderful things that has happened in America.”

Organized by the Detroit Council on Human Rights, this was the largest Civil Rights demonstration to date. Its main purpose was to speak out against Southern segregation and the brutality that faced Civil Rights activists there. It was also meant to raise consciousness about the unique concerns of African Americans in the urban North, which included discriminatory hiring practices, wages, education, and housing. The date was chosen to correlate with both the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and the 20th anniversary of the 1943 Detroit race riots that had left 34 people (mostly African American) dead. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who agreed to lead the march, had by this time become committed to uniting both North and South through his grand vision of achieving racial justice by using non-violent protest.

On the day of the march, about 125,000 people filed down Woodward Avenue, singing freedom songs and carrying signs demanding racial equality. Some 15,000 spectators watched them pass by a 21-block area before turning west down Jefferson Avenue to Cobo Hall. Cobo was filled to capacity to hear the speeches of the march’s leaders while thousands more listened to them on loudspeakers outside. Of the speeches given that day, Dr. King’s was the most memorable. People were riveted while he expressed his vision for the future, sharing a dream that foreshadowed the “I Have a Dream” speech that he would give a few months later at the March on Washington.

Berry Gordy, founder of the Motown Record Corporation, considered Detroit’s Walk to Freedom to be such a historic event that he offered the resources of his Hitsville studio to produce a record album documenting Dr. King’s impassioned words. Gordy heightened the drama of the event by titling the album, “The Great March to Freedom: Reverend Martin Luther King Speaks.” He believed that this record belonged in every home, that it should be required listening for “every child, white or black.” No one realized at the time, including Gordy, that the August March on Washington would become the more remembered event.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dreams of social justice, voiced at Detroit’s Walk to Freedom, would prove elusive. Despite the fact that Detroit had gained a national reputation for being a “model city” of race relations at the time, in reality the city’s African-American population faced unemployment, housing discrimination, de facto segregation in public schools, and police brutality. Ultimately this disconnect between perception and reality would lead to the violence and civil unrest of July 1967.

For more on the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom held on August 28, 1963, take a look at this post.

Donna R. Braden is the Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

1960s, 20th century, music, Michigan, entrepreneurship, Detroit, Civil Rights, by Donna R. Braden, African American history

Dale Earnhardt Iconic Victory

Pennant, "Dale Earnhardt, #3," 2000. THF251065

Dale Earnhardt Sr. is truly one of NASCAR’s greatest legends, with a total of 76 career victories and seven NASCAR Cup championships on the way to becoming a first-ballot NASCAR Hall of Famer.

But one victory, 20 years ago today, will always be special. The 1998 Daytona 500 was the race that Dale Earnhardt finally broke through and won “The Great American Race” in his 20th attempt.

Ironically, Earnhardt was considered a Daytona race master. He had won 11 Daytona 500 qualifying races, six Busch Clash races, four IROC all-star races, two 400-mile July races, and seven Grand National (now XFINITY Series) events at the famed 2.5-mile tri-oval.

That’s 30 victories at the track he loved - a place where legend was he could “see the air” in the draft of cars. It was a place where he was feared by the other competitors because he was so good in competition there.

But a series of mishaps in the biggest race of them all – the Daytona 500 – had hampered him in chasing the trophy he wanted most. Once, he won the Daytona 499 ½, cutting a tire going through the final two turns and losing the chance to win. Other times he had the dominant car only to be beaten by fuel strategy. Or he’d come runner-up in a battle to the finish line.

But that was all forgotten on Feb. 15, 1998, when Dale Earnhardt, once again dominant, led 107 of the race’s 200 laps to take his long-awaited victory in the third fastest 500 in history at that time.

The post-race scene was emotional as Earnhardt slowly rolled down pit lane, with every crew member from every team greeting him with high fives and slaps on his black No. 3 Chevrolet.

The streak had been broken and Dale Earnhardt finally got the trophy he always wanted.

Sadly, just three years later, again in the Daytona 500, Earnhardt was killed in a last lap crash in Turn 4 while attempting to block for his team cars of Michael Waltrip and his son Dale Jr., who went on to finish 1-2.

Kevin Kennedy is a guest writer to The Henry Ford.

Florida, 21st century, 2010s, 20th century, 1990s, racing, race car drivers, cars, by Kevin Kennedy

Remembering Lincoln

This statue was designed to reveal Lincoln’s “essential nobility” while the inscription above him was intended to reinforce national unity. THF121596

By the first decade of the 20th century, memories of the real Abraham Lincoln had faded. A new generation of Americans came of age who had only heard the stories, the myths, and the legends. It was this generation who transformed Lincoln the real man into Lincoln the hero.

During the early decades of the 20th century, America was becoming a complex place--an urban-industrial nation, a serious player on the world stage, and a place with an increasingly diversified population of foreign-born residents. Struggling to come to terms with the change and uncertainty of the era, people looked to Abraham Lincoln--the humble, imperfect, self-educated “common man”--for comfort and reassurance. Abraham Lincoln, better than any single individual, seemed to embody the democratic principles upon which the country had been founded. It was during this era that Abraham Lincoln replaced George Washington as America’s most venerated president.

Just about everyone could find something meaningful by invoking his image, his name, or his character.

The Lincoln Centennial

Postcards abounded as popular keepsakes of the Lincoln Centennial, including this German-imported embossed example. THF121598

On February 12, 1909, virtually the entire nation honored Abraham Lincoln on the 100th anniversary of his birth. In city after city, Americans put aside their regional differences and sought national unity by venerating Lincoln as a “man of the people.”

The national celebration was a grassroots effort--mainly the work of local governments, civic organizations, and print media. Even in the old Confederate states, Lincoln’s character was held up as a model of humility and generosity.

Sadly, Jim Crow laws in the South and practices in the North prevented African Americans from taking part in most of these observances. In their own communities, they honored the memory of Lincoln as the “Great Emancipator.”

The Lincoln Highway

Abraham Lincoln and symbols of national unity are pictured on the front of this 1915 travelogue. THF204498

In 1912, the few “good” roads that existed for automobile travel were dirt-covered--making them bumpy and dusty in dry weather and virtually impassable when it rained. To get anywhere, it was better to take a train than to drive.

Enter Carl Fisher, an automobile headlight entrepreneur who had the ambitious idea of creating a highway that would cross the continent from New York City to San Francisco. He turned to manufacturers of automobiles and automobile accessories for support and financial backing. His biggest advocate became Henry Joy, president of the Packard Motor Car Company.

It was Joy’s idea to name the road in honor of Abraham Lincoln. Joy was only a year old when Lincoln was assassinated but his father had filled him with stories of the martyred president. He felt that connecting the road with Lincoln would both increase both its patriotic appeal and enhance its symbolism as the road that unified the nation--a fitting parallel to Lincoln’s great achievement of preserving the union.

Abraham Lincoln and World War I

This World War I poster includes an excerpt of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. THF239921

During the First World War, Lincoln’s reputation extended beyond American shores to the international arena. For, who could more perfectly symbolize the international fight for freedom--the fight to make the world safe for democracy--than America’s own Abraham Lincoln? Although Lincoln’s tactics as Commander-in-Chief during the Civil War had been questioned during his own time, his policies, decisions, defense of war, and crackdown on obstructionists now seemed to exemplify visionary leadership.

Reviving Lincoln as a symbol of wisdom, courage, and sacrifice during World War I might have been propaganda but it worked its magic on the American public. Northerners and Southerners enlisted in droves and fought alongside each other in battle. African Americans’ loyalty to Lincoln inspired thousands to enlist and bravely serve their country--though largely in segregated units.

Lincoln Logs

This Lincoln Logs set dates from about 1960—the era of TV Westerns and the Davey Crockett craze. THF6627

Beloved by generations of young children, Lincoln Logs have been around since the 1920s. Oddly, their origin had nothing to do with Abraham Lincoln or log cabins. John Lloyd Wright, Lincoln Logs inventor and son of the famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, claimed that the idea for this sturdy, interlocking “log” playset came to him in Tokyo, Japan in 1916, while visiting the construction site of the hotel designed by his father. The Imperial Hotel, as it was named, was built upon a unique, earthquake-proof foundation of interlocking beams.

By the time Wright patented his invention in 1920, he was calling it a “Toy-Cabin” construction set. In 1924, it came on the market as “Lincoln Logs: America’s National Toy.” Further cementing the connection, a 1928 advertisement claimed that Lincoln Logs provided, “All the romance of the early days of Abraham Lincoln with all the thrill of Pioneer Life.” Lincoln Logs were an instant success--leading to larger and more elaborate play sets that included cowboys, pioneer towns, forts, horses, and livestock.

The Lincoln Memorial The Greek temple-like design of the Lincoln Memorial symbolizes the democratic principles for which Lincoln stood. THF121594

The Greek temple-like design of the Lincoln Memorial symbolizes the democratic principles for which Lincoln stood. THF121594

During the 1909 Lincoln Centennial, Congress found itself in the embarrassing position of having no plans to honor Lincoln in the nation’s capital. So in 1911, a Lincoln Memorial Commission was created. The commissioners saw this Memorial as both a tribute to Lincoln and an important symbol of a reunified nation. They chose to avoid any literal references to Lincoln’s accomplishments as President as well as his role as the “Great Emancipator.” They felt that might offend people, especially Southerners. No, this expression of Lincoln must transcend all that to represent the man who defended democracy and saved the Union. It must idealize Lincoln’s memory and reveal his “essential nobility.”

After delays in the completion of the enormous statue, the Lincoln Memorial was finally dedicated in 1922. In keeping with federal policies on segregation, African American guests to the dedication were seated in a “colored section” off to the side, where they reported rude treatment by military attendants.

Henry Ford and Abraham Lincoln In this 1934 photograph, Henry Ford poses in front of the Logan County Courthouse with Lincoln portrayer Charles Roscoe Miles. THF121394

In this 1934 photograph, Henry Ford poses in front of the Logan County Courthouse with Lincoln portrayer Charles Roscoe Miles. THF121394

In his great admiration for Abraham Lincoln, Henry Ford was like many other Americans of his generation. Born two years before Lincoln was assassinated, he had grown up surrounded by Lincoln myths and stories. His Uncle Barney’s regiment--the Union Army’s famed 24th Michigan Volunteer Infantry--had even escorted President Lincoln’s casket from the Old State House in downtown Springfield, Illinois, to its final resting place in Oak Ridge Cemetery about two miles away.

As Henry grew from a youth to an enterprising automobile entrepreneur, Lincoln’s lessons were not lost on him. According to the stories, Lincoln’s success had been due to such character traits as honesty, temperance, industry, and pluck. Furthermore, Lincoln embodied the ideals of the “self-made man,” rising up from humble beginnings to make something of himself.

By the 1920s, a now-wealthy Henry Ford began to amass a collection to honor his hero--including the rocker that Lincoln had been sitting in at Ford’s Theatre the night he was assassinated. When an antique dealer friend told him of a neglected courthouse in Lincoln, Illinois, in which Lincoln had practiced law, Henry Ford knew that this was the key he had been searching for. It would become the centerpiece of an “exhibit” in his Early American Village (now Greenfield Village) depicting the move from slavery to emancipation. The building would also house his Lincoln collection, to serve as a teaching tool for “the application of the practical principles of justice and common sense so often exemplified by Abraham Lincoln in real life.” Ford’s workmen dismantled and reconstructed the courthouse in Greenfield Village in record time for its grand opening on October 21, 1929.

75 Years of Negro Progress Exposition Lincoln’s image looms large in this poster advertising the nine-day Negro Progress Exposition. THF61510

Lincoln’s image looms large in this poster advertising the nine-day Negro Progress Exposition. THF61510

Abraham Lincoln remained a powerful source of inspiration to African Americans through the early 20th century, as they struggled to realize the promise of emancipation. The image of Lincoln as the “Great Emancipator” belonged particularly to them. Those who had experienced firsthand Lincoln’s gift of freedom from slavery considered him their savior and they passed down to younger generations the intensely personal love and reverence they felt for him.

Seventy-five years after Lincoln was assassinated, Detroit was host to a nine-day exposition celebrating both past achievements and “new horizons of advancement.” Each day of the Exposition offered a theme, including Business Day, Women’s Day, Race Relations Day, Youth and Athletic Day, and Patriotic Day. Joe Louis, World’s Heavyweight Champion, made an appearance and Dr. George Washington Carver’s laboratory was featured.

In reality, progress for African Americans had been and would continue to be slow. Most of the earlier dreams of freedom and racial equality had failed. Jim Crow laws and practices were very much in effect. Discrimination was widespread, in the North as well as the South. Race riots continued. It would be 15 more years before Rosa Parks would refuse to give up her seat on a bus, sparking the Civil Rights movement. Later Civil Rights leaders would, in fact, downplay Lincoln’s role in their plight--feeling that reinforcing his image as the “Great Emancipator” diminished their own struggles and African Americans’ own contributions.

Donna Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. This post originally ran as part of our Pic of the Month series.

20th century, presidents, by Donna R. Braden, Abraham Lincoln

The Tucker 48: “The Car You Have Been Waiting For”

The 1948 Tucker

The Tucker '48 automobile, brainchild of Preston Thomas Tucker and designed by renowned stylist Alex Tremulis, represents one of the most colorful attempts by an independent car maker to break into the high-volume car business. Ultimately, the Big Three would continue to dominate for the next forty years. Preston Tucker was one of the most recognized figures of the late 1940s, as controversial and enigmatic as his namesake automobile. His car was hailed as "the first completely new car in fifty years." Indeed, the advertising promised that it was "the car you have been waiting for." Yet many less complimentary critics saw the car as a fraud and a pipe dream. The Tucker's many innovations were and continue to be surrounded by controversy. Failing before it had a chance to succeed, it died amid bad press and financial scandal after only 51 units were assembled.

Much of the appeal of the Tucker automobile was the man behind it. Six feet tall and always well-dressed, Preston Tucker had an almost manic enthusiasm for the automobile. Born September 21, 1903, in Capac, Michigan, Preston Thomas Tucker spent his childhood around mechanics' garages and used car lots. He worked as an office boy at Cadillac, a policeman in Lincoln Park, and even worked for a time at Ford Motor Company. After attending Cass Technical School in Detroit, Tucker turned to salesmanship, first for Studebaker, then Stutz, Chrysler, and finally as regional manager for Pierce-Arrow.

As a salesman, Tucker crossed paths at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway with the great engine designer Harry A. Miller, and in 1935 they formed Miller-Tucker, Inc. Their first contract was to build race cars for Henry Ford. The company delivered ten Miller-Ford Indy race cars, but they proved inadequate for Ford and he pulled out of the project.

During World War II, automobile companies' operations were dedicated to the war effort. Denied new car models for four years, by the war's end Americans were eager for a new automobile, any new automobile. The time was right for Tucker to begin his dream. In 1946, he formed Tucker Corporation for the manufacture of automobiles.

Tucker Corporation employee badge. THF135737

He set his sights on the old Dodge plant in the Chicago suburb of Cicero, Illinois. Spanning over 475 acres, the plant built B-29 engines during World War II, and its main building, covering 93 acres, was at the time the world's largest under one roof. The War Assets Administration (WAA) leased Tucker the plant provided he could have $15 million dollars capital by March 1 of the following year. In July, Tucker moved in and used any available space to build his prototype while the WAA inventoried the plant and its equipment.

The fledgling company needed immediate money, and Tucker soon discovered that support from businessmen who could underwrite such a venture meant sacrificing some, if not all, control of his company. To Tucker, this was not an option, so he conceived of a clever alternative. He began selling dealer franchises and soon raised $6 million dollars to be held in escrow until his car was delivered. The franchises attracted the attention of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and in September of 1946 it began an investigation, the first of a series that would last for the next three years.

The agreements were rewritten to SEC satisfaction and the franchise sales proceeded. In October, Tucker began another proposal: a $20 million stock issue contingent upon a completed prototype and clearance by the SEC. That same month, Tucker met his first serious obstacle. Wilson Wyatt, head of the National Housing Agency, ordered the WAA to cancel Tucker's lease and turn the plant over to the Lustron Corporation to build prefabricated houses.

Tucker may have been an unfortunate pawn in a bureaucratic war between the housing agency and the WAA, but the battle continued until January of 1947. Franchise sales fell, stock issues were delayed, and Tucker's reputation was severely damaged. In the end, he kept his plant, but the episode made him some real enemies in Washington, including Michigan Senator Homer Ferguson. But Tucker did find some allies. The WAA extended Tucker's $15 million cash deadline to July 1 and Senator George Malone of Nevada began his own investigation of the SEC.

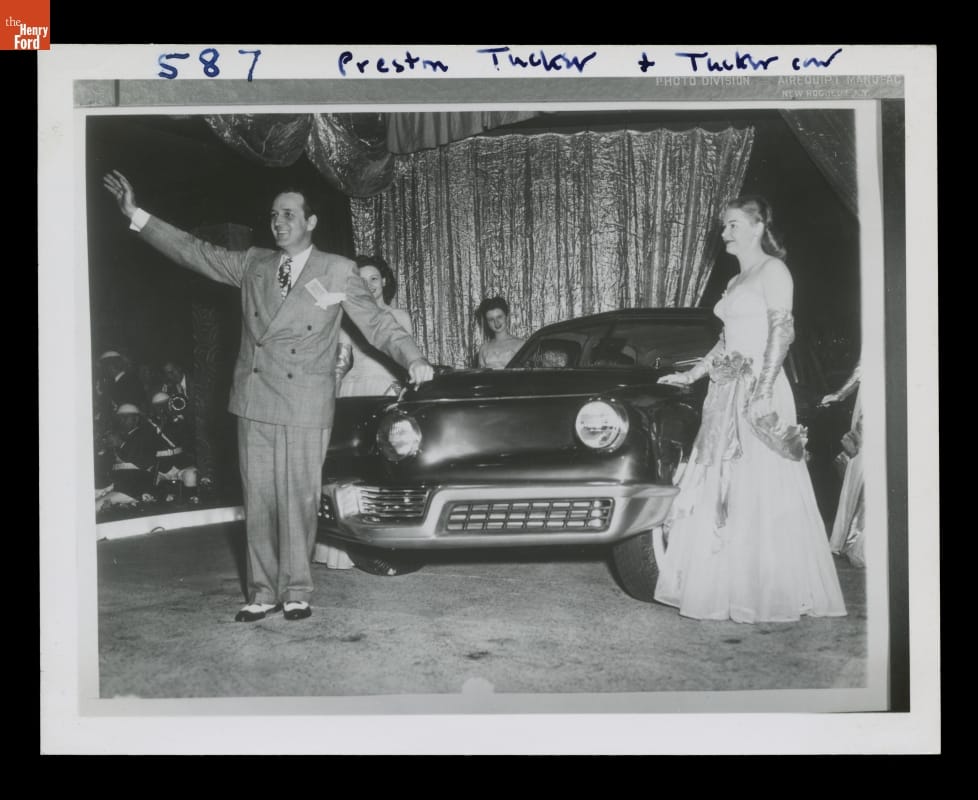

Meanwhile, Tucker still had a prototype to build. During Christmas 1946, he commissioned Alex Tremulis to design his car and ordered the prototype ready in 100 days. The time frame was unheard of, but necessary. Unable to obtain clay for a mock-up, engineers – many from the race car industry – began beating out sheet iron, a ridiculous way to build a car but a phenomenal achievement. The first car, completely hand-made, was affectionately dubbed the "Tin Goose." Preston Tucker unveils his car, June 19, 1947. THF135047

Preston Tucker unveils his car, June 19, 1947. THF135047

The Tucker '48 premiered June 19, 1947, in the Tucker plant before the press, dealers, distributors and brokers. Tucker later discarded many of the Tin Goose's features, such as 24-volt electrical system starters to turn over the massive 589-cubic-inch engine. For the premier, workers substituted two 12-volt truck batteries weighing over 150 pounds that caused the Tucker's suspension arms to snap. Speeches dragged on as workers behind the curtain tried feverishly to get the Tin Goose up and running. Finally, before the crowd of 5000, the curtains parted and the Tucker automobile rolled down the ramp from the stage and to its viewing area where it remained for the rest of the evening. Stock finally cleared for sale on July 15.

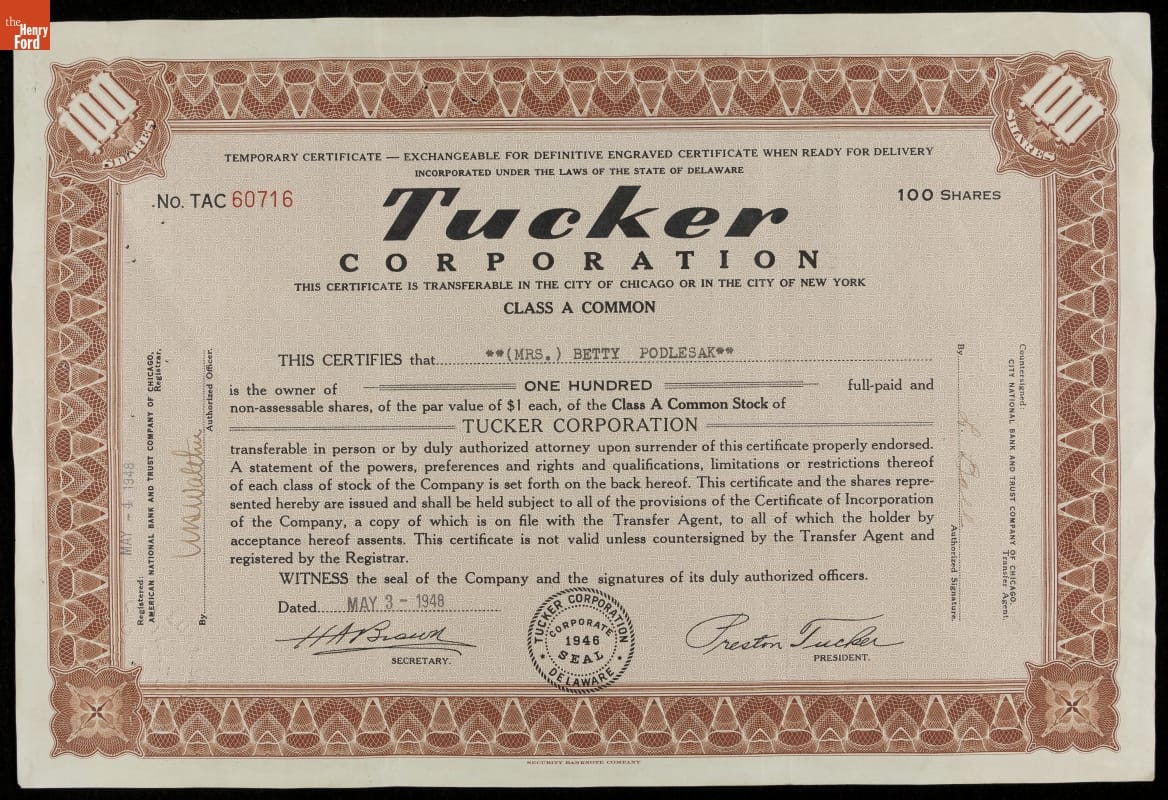

By the spring of 1948, Tucker had a pilot production line set up but his stock issue had been $5 million short and he again needed immediate money. He began a pre-purchase plan for Tucker automobile accessories such as radios and seat covers. Although he raised $1 million, advanced payment on accessories to a car not yet in production was the final straw for the SEC. On May 28, 1948, the SEC and the Justice Department launched a full-scale investigation. Investigators swarmed the plant and Tucker was forced to stop production and lay off 1,600 workers. Receivership and bankruptcy suits piled up, creditors bolted, and stock plunged. A Tucker stock certificate for 100 shares, dated May 3, 1948. THF208633

A Tucker stock certificate for 100 shares, dated May 3, 1948. THF208633

The SEC's case had to show that the Tucker car could not be built, or – if built – would not perform as advertised. But Tucker was building cars. Seven Tuckers performed beautifully at speed trials in Indianapolis that November, consistently making 90 mph lap speed. However, after Thanksgiving, a skeletal crew of workers assembled the last cars that the company would ever produce. In January 1949, the plant closed and the company was put under trusteeship.

"Gigantic Tucker Fraud Charged in SEC Report" ran the Detroit News headline in March. The article related an SEC report recommending conspiracy and fraud charges against Preston Tucker. Incensed, Tucker demanded to know how the newspaper had seen the report even before him. SEC Commissioner John McDonald later admitted he delivered the report to the paper in direct violation of the law. Feeling tried and convicted by the press, Tucker wrote an open letter to many newspapers around the country.

On June 10, Tucker and seven of his associates faced a Grand Jury indictment on 31 counts – 25 for mail fraud, 5 for SEC regulation violation, and one on conspiracy to defraud. The trial opened on October 5, 1949, and from the beginning the prosecution based its entire case on the "Tin Goose" prototype. It refused to recognize the 50 production cars and called witness after witness who, under cross-examination, ended up hurting the government's case. In the end, Tucker's defense team merely stated that the government had failed to prove any offense so there was nothing to defend.

On January 22, 1950, the jury found the defendants innocent of any attempt to defraud, but the verdict was a small triumph. The company was already lost. The remaining assets, including the Tucker automobiles, were sold for 18 cents on the dollar. Seeking some recompense, Preston Tucker filed a series of civil suits against news organizations that he believed had defamed him in the months leading up to his trial. His targets included the Detroit News, which he hit with a $3 million libel suit in March 1950.

In preparation for its defense, the Evening News Association – publisher of the Detroit News – acquired Tucker serial number 1016 for examination. But the suit never reached the courtroom. Preston Tucker was diagnosed with lung cancer and died December 26, 1956. The Evening News Association subsequently presented car 1016 to The Henry Ford, where it remains today.

Illinois, Michigan, 20th century, 1940s, manufacturing, entrepreneurship, cars

Segregated Travel and the Uncommon Courage of Rosa Parks

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks, a soft-spoken African American seamstress, was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white man on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. This led to a city-wide bus boycott by the African American community that was so successful many consider Rosa Parks’ act to be the event that sparked the Civil Rights movement.

It’s a powerful story: one person’s simple act of courage can change the world. Today it’s difficult to imagine the real risks that Rosa Parks faced and the tremendous amount of courage she possessed in refusing to give up her seat that day. To get a better sense of this, we must explore the nature of segregated travel in the Jim Crow South.

Separate and Unequal

Jim Crow laws -- first enacted in the 1880s by angry and resentful Southern whites against freed African Americans -- separated Blacks from whites in all aspects of daily life. Favoring whites and repressing Blacks, these became an institutionalized form of inequality.

Jim Crow was a character created for a minstrel-show act during the 1830s, the date of this sheet music. The act -- featuring a white actor wearing Black makeup -- was meant to demean and make fun of African Americans. THF98689

In the Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states had the legal power to require segregation between Blacks and whites. Jim Crow laws - now legally enforceable - spread across the South virtually anywhere that the two races might come in contact. Many of these practices lasted into the 1960s, until outlawed by the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Through separate (and inferior) public facilities like building entrances, elevators, cashier windows, and drinking fountains, African Americans were reminded everywhere of their second-class status. THF13419 and THF13421

Through separate (and inferior) public facilities like building entrances, elevators, cashier windows, and drinking fountains, African Americans were reminded everywhere of their second-class status. THF13419 and THF13421

Travel in the segregated South was particularly humiliating for African Americans, beginning with railroads back in the 19th century. Traveling in or between southern states by railway, African Americans of all economic classes were generally relegated to primitive, uncomfortable "Jim Crow cars." Located just behind the locomotive, these were also the most dangerous cars should a collision or boiler explosion occur. Any Black railway passenger who complained or refused to comply with the rules could be forcibly removed from the train, beaten, or even killed. Conductors in some states were given policing power to enforce the rules or they could summon local police at station stops to back them up. Southern states established segregated railroad station facilities for Blacks, with separate (and often inferior) ticket agent windows and restrooms, and often lacking the eating facilities available to whites. This sign was installed in a Louisville & Nashville Railroad station. THF93445

Southern states established segregated railroad station facilities for Blacks, with separate (and often inferior) ticket agent windows and restrooms, and often lacking the eating facilities available to whites. This sign was installed in a Louisville & Nashville Railroad station. THF93445

The coming of affordable automobiles seemed to provide southern Blacks with a way to get around the indignities of long-distance rail travel. However, as soon as Black motorists stopped along the road, Jim Crow laws returned in force. Service station and roadside restrooms were usually closed to African Americans, so they often resorted to stashing buckets or portable toilets in their trunks. Diners and restaurants regularly turned away Black customers, who took to bringing food along with them. Roadside motels often refused to admit Blacks, so they had to depend on the hospitality of their own people or chance the discovery of a "Negro" rooming house.

To avoid Jim Crows laws while travelling in the South (and unwritten Jim Crow practices followed in the North), Black motorists created their own tourist infrastructure, with specially published guides steering them to safe accommodations. This is the 1949 edition of "The Negro Motorist Green Book," produced by postal employee Victor H. Green, of Harlem, New York, from 1936 until the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. THF77183

Physically separating Blacks and whites was most difficult on city transit systems. By 1905, every southern state had outlawed Blacks from sitting next to whites on trolleys and streetcars, while individual conductors usually ordered black patrons to move from this or that seat. Middle-class Blacks were particularly indignant about these laws and organized numerous long-forgotten boycotts and protests. But, like railroad conductors before them, streetcar conductors were given policing power - and even weapons - to enforce the laws. Any Blacks who challenged the rules of behavior were dealt with swiftly and harshly.

As buses replaced trolleys and streetcars on city streets, Jim Crow laws continued. Each state and city had different requirements and customs to signal how Blacks and whites were to be separated on the buses. But, as with earlier modes of transportation, individual drivers had great latitude in determining where people sat and the power to enforce their decisions.

By the 1950s, as many as 40,000 African Americans regularly rode the city buses in Rosa Parks’ home town of Montgomery, Alabama (compared with about 12,000 whites). Officially, 10 seats in the front of each bus were reserved for whites. These spaces were reserved no matter what. Often this meant Black riders were jammed in the aisle, standing over empty seats. If the white section filled up and more white riders came in, an entire row of Black passengers had to get up and move back. Bus drivers could demand more seats for whites at any time and in any number. Furthermore, drivers often forced African American riders, once they had paid their fare, to get off the bus and re-enter through the back door-sometimes driving away without them. (Rosa Parks had actually experienced this.) Those who didn’t comply with these rules could be not only verbally abused but also slapped, knocked on the floor, pushed out the door, beaten, or even killed (which did occur in a few little-publicized cases).

A Courageous Act

As stories of abusive drivers and humiliating incidents continued to spread, anger in the black community grew. However, most of the time, the indignities went unchallenged. Expecting African Americans to resist these long-established laws and traditions meant asking them to risk great harm and to summon an extraordinary amount of personal courage.

By 1955, inspired by attempts in other cities, Black community leaders in Montgomery explored the idea of a city-wide bus boycott - an organized refusal to use the buses. But they would need the united support of the city's African American bus riders, a notion that was unprecedented, untested, and likely to fail given past experience. And, after some fits and starts in trying to find an appropriate test case, they realized that a successful boycott would require the determined action of someone who possessed a flawless character and reputation and, at the same time, could ignite the action of an entire community.

That person, it turned out, was Rosa Parks. Her action on December 1, 1955, was unplanned and spontaneous, although her life experiences had undoubtedly prepared her for that moment. She was not the first African American to challenge the segregation laws of the Montgomery city bus system. But her sterling reputation, her quiet strength, and her moral fortitude caused her act to successfully ignite action in others.

This Montgomery city bus, acquired by The Henry Ford in 2001, is the actual bus on which Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat back in 1955. It now resides in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation's With Liberty & Justice For All exhibition. THF134576

Sparking a Movement

Rosa Parks’ arrest for defying the Jim Crow law of segregation on Montgomery buses led to an immediate city-wide bus boycott, during which the Black community shared rides, walked, or worked out carpools-despite burnings, bombings, gunshots, and arrests. The Montgomery bus boycott lasted more than one year - 381 days to be exact -until the U.S. Supreme Court finally declared segregation on Alabama buses to be unconstitutional.

Rosa Parks' simple, courageous act gave African Americans everywhere a new sense of pride and purpose, and inspired non-violent protests in other cities. Because of this, many consider her singular act of protest on the bus to be the event that sparked the Civil Rights movement.

Unfortunately, the impact of her act took its toll on Rosa Parks herself. She lost her job, her marriage became strained, her quiet life was gone, and she received threatening phone calls and letters. In 1957, she left Montgomery, moving to Detroit and eventually working for Congressman John Conyers.

How did Rosa Parks summon the courage to defy decades of established rules and traditions about segregated travel? A few months after her arrest, she explained it like this:

The time had just come when I had been pushed as far as I could stand to be pushed, I suppose. I had decided that I would have to know, once and for all, what rights I had as a human being, and a citizen, even in Montgomery, Alabama.

Rosa Parks was not a civic, political, or religious leader. She was just an ordinary person. And she well knew the risks of her actions. But, through her example, she showed others what was possible. Her uncommon courage shines through as an inspiration to us today.

Donna Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford. This post originally ran as part of our Pic of the Month series.

Additional Readings:

- With Liberty and Justice for All

- Rosa Parks Bus

- "Colored" Drinking Fountain, 1954

- Museum Icons: The Rosa Parks Bus

Alabama, 1950s, 20th century, women's history, travel, Rosa Parks, by Donna R. Braden, African American history

Charlie Sanders: Detroit Lions Icon

Ring received by Charlie Sanders when he was enshrined at the Pro Football Hall of Fame. THF165545

The Henry Ford has in its collection this commemorative bust and ring that had once been owned and cherished by Charlie Sanders, Detroit Lions tight end. He had received these items when he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame on August 4, 2007, along with five other players.

The Pro Football Hall of Fame was created in Canton, Ohio, in 1963, to commemorate the game and players of professional football. As of 2017, 310 players are enshrined here, elected by a 46-person committee that is mostly made up of members of the media. An Enshrinement Ceremony is held annually in August. Thousands attend this ceremony and millions more watch and listen as the nationally televised event unfolds.

Sanders is one of 19 Lions enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Seven of the 19 are African American, including Lem Barney, Barry Sanders, and Dick “Night Train” Lane.

Charlie Alvin Sanders (1946-2015) was born in rural Richlands, North Carolina, where his aunt raised him after the death of his mother when he was only two years old. At age 8, after his father got out of the military, the family moved to Greensboro—a hotbed of racial tension, most famously the Greensboro lunch counter sit-ins of 1960.

He graduated from James B. Dudley High School (Greensboro’s first all-black public school, established in 1929). There he starred in football, baseball, and basketball. His dislike of Southern racial attitudes discouraged him from attending North Carolina’s Wake Forest University; he decided instead to play football at the University of Minnesota.

The Detroit Lions chose him in the third round of the 1968 NFL Draft. Initially, he wasn’t sure about playing for Detroit after witnessing the civil unrest in that city in 1967, reminding him of the racial tensions in the South when he was growing up. He almost went to Toronto to play hockey, but the Lions offered him a contract he decided to accept.

Sanders has been considered the finest tight end in Detroit Lions history. He played for the Lions from 1968 to 1977, totaling 336 career receptions (a Lions record that would hold for 20 seasons) for 4,817 yards and 31 touchdowns. He was also known as a superior blocker.

The tight end was a unique offensive position that, depending upon the coach’s strategy, can assist with blocking for the running back or quarterback as well as receive passes. Greater use of the tight end as a receiver started in the 1960s. Sanders proved to be the Lions’ “secret weapon” in the passing game during a period when the right end was primarily a blocker. He was one of the first tight ends who brought experience in both college football and basketball, and he had great leaping ability, big hands, strength, speed and elusiveness—traits not common for tight ends of his era. Hall of Fame Cornerback Lem Barney claimed, “He made some acrobatic catches. I’m telling you, one-legged, one arm in the air, floating through the air almost like a Superman. If you threw it to him he was going to find a way to catch it.”

Sanders grew up in an era that marked the transition between legally upheld segregation in the South and increasingly prominent roles of African Americans in all aspects of sports—on the playing field, in media, and as decision-makers in coaching and management. He came of age at a time when the black athlete in Detroit aspired to a more activist role in social and business matters. He spent much time in the company of Lions teammates Lem Barney and Mel Farr and Pistons star Dave Bing. Referring to themselves as “The Boardroom,” they frequently conducted meetings in which they discussed the importance of black athletes being defined by more than simply their on-field exploits.

Sanders’ look defined African American players of the 1970s. As writer Drew Sharp remarked, “He wore the huge Afro. His helmet couldn’t cover it all. It looked cool. It looked defiant. And, quite frankly, it was the only motive for any kids in my northwest Detroit neighborhood to buy a Lions helmet at that time because they wanted their Afros sticking out from the back.” He also sported a heavy Fu Manchu mustache at the time.

Bust received by Charlie Sanders when he was enshrined at the Pro Football Hall of Fame. THF165545

During his 10 years playing for the Lions, he was chosen seven times for the Pro Bowl (NFL’s All-Star game) from 1968 to 1971 and 1974 to 1976—more than any other Hall of Fame Tight End. He was also chosen for NFL’s All-Pro team in 1970 and 1971 (made up of players voted the best in their position during those two years) and for the NFL’s 1970s All-Decade Team. In 2008, he was chosen as a member of the Lions’ 75th Anniversary All-Time Team.

During an exhibition game in 1976, Sanders injured his right knee, ending his career. After retirement, Sanders served as a color analyst for Lions radio broadcasts (1983-1988), worked with the team as an assistant coach in charge of wide receivers (1989-1996 – mentoring players who would themselves go on to earn a place in the Lions’ record book), returned to radio broadcasting in 1997, then joined the Lions’ front office as a scout. He became the team’s assistant director of pro personnel in 2000, holding that role until his death on July 2, 2015.

Sanders had also worked in the team’s community relations department and did much charitable work, serving as a spokesman for the United Way and The March of Dimes. He created The Charlie Sanders Foundation in 2007, providing scholarships for high school students in Michigan and North Carolina, and began the “Have a Heart Save a Life” program within the foundation.

Sanders spent 43 years with the Detroit Lions over parts of five decades, the longest tenure of anyone outside the Ford family. Sports blogger “Big Al” Beaton wrote about him, “…as a kid growing up in the 70’s, my favorite Lion was Charlie Sanders….We all wanted to emulate Charlie Sanders. In my mind Sanders was the best tight end I’ve ever seen play.”

Donna R. Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 20th century, sports, Michigan, football, Detroit, by Donna R. Braden, African American history

Losing Weight, 1972-Style

Jar of Weight Watchers “Sweet’ner,” 1972. THF170107

Many diet plans have come and gone. But, through its innovative approach and changing strategies that attempt to keep up with the times, the Weight Watchers program has endured for more than 50 years. Recently, we came across this rather mysterious jar of Weight Watchers sugar substitute from 1972. This led us to unearth the intriguing origins and changing strategies of the Weight Watchers program as well as the ongoing controversies about non-caloric sweeteners.

Weight Watchers was founded in 1963, by Jean Nidetch, an overweight, 40-year-old homemaker living in Queens, New York. Constantly struggling with dieting but never able to keep off her weight, she called up a few friends one day to come over and share their weight loss struggles. Within a short time, these meetings became so popular that she began to arrange support group meetings and realized that by sharing their stories and supporting each other, people were starting to change their eating habits. Al Lippert, a merchandise manager who lost 40 pounds through these weekly meetings, began to give Nidetch advice on how to organize and expand her activities and soon a four-person partnership was formed among Nidetch and her husband, Marty, and Al and Felice Lippert. In May 1963, Weight Watchers was incorporated and opened for business in Queens, New York.

This jar of “Sweet’ner” mostly contained saccharin. The 1972 Weight Watchers program did not permit the consumption of sugar (except in “legal” recipes) and, instead, promoted the use of its artificial sweetener in all recipes, dishes, and beverages. The promise of this simple-to-use, calorie-free product helped bring new members into the program. At the same time, Weight Watchers introduced a new line of artificially sweetened foods and sodas.

Booklet with “calorie saving recipes” using Sucaryl (cyclamate), 1955. THF286634

Synthetic sweeteners have always seemed like miracle foods. The promise of a calorie-free treat or drink has had a stronger pull than the health and safety risks that might accompany them (such as causing cancer or possibly actually encouraging weight gain). This is why it seems that, as soon as one sweetener is declared dangerous, the next big sweetener is just around the corner. Saccharin, accidently discovered in 1897 by a Johns Hopkins University researcher, was the first widely used artificial sweetener. But some thought it to be dangerous and toxic. The introduction of a sweetener called cyclamate, discovered 1937, replaced it in popularity and it coincided with the diet soda boom of the 1950s and 1960s. But the use of cyclamates came to a halt when it was banned by the FDA in 1969, as it was found to cause cancer in rats. Saccharin, by then popular in Sweet ‘n’ Low, was banned in 1981 for its cancer-causing risks but it was unbanned in 2010 in more than 100 countries, including the United States. Meanwhile, other non-caloric sweeteners became popular, including Aspartame (used in NutraSweet and Equal) and Sucralose (used in Splenda). Each of these came with health and safety risks.

Despite competition, food fads, and uneven business expansion efforts, Weight Watchers has maintained its dominance in the weight loss business and, through continual refinement and addressing consumer needs, remains as popular as ever.

Donna R. Braden is Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 1970s, home life, healthcare, food, by Donna R. Braden

Remembering Dan Gurney (1931-2018)

Dan Gurney at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, 1963. THF114611

The Henry Ford is deeply saddened by the loss of a man who was both an inspiration and a friend to our organization for many years, Dan Gurney.

Mr. Gurney’s story began on Long Island, New York, where he was born on April 13, 1931. His father, John Gurney, was a singer with the Metropolitan Opera, while his grandfather, Frederic Gurney, designed and manufactured a series of innovative ball bearings.

The Gurneys moved west to Riverside, California, shortly after Dan graduated high school. For the car-obsessed teenager, Southern California was a paradise on Earth. He was soon building hot rods and racing on the amateur circuit before spending two years with the Army during the Korean War.

Following his service, Gurney started racing professionally. He finished second in the Riverside Grand Prix and made his first appearance at Le Mans in 1958, and earned a spot on Ferrari’s Formula One team the following year. Through the 1960s, Gurney developed a reputation as America’s most versatile driver, earning victories in Grand Prix, Indy Car, NASCAR and Sports Car events.

His efforts with Ford Motor Company became the stuff of legend. It was Dan Gurney who, in 1962, brought British race car builder Colin Chapman to Ford’s racing program. Gurney saw first-hand the success enjoyed by Chapman’s lithe, rear-engine cars in Formula One, and he was certain they could revolutionize the Indianapolis 500 – still dominated by heavy, front-engine roadsters. Jim Clark proved Gurney’s vision in 1965, winning Indy with a Lotus chassis powered by a rear-mounted Ford V-8. Clark’s victory reshaped the face of America’s most celebrated motor race.

Simultaneous with Ford’s efforts at Indianapolis, the Blue Oval was locked in its epic battle with Ferrari at the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Again, Dan Gurney was on the front lines. While his 1966 race, with Jerry Grant in a Ford GT40 Mark II, ended early with a failed radiator, the next year brought one of Gurney’s greatest victories. He and A.J. Foyt, co-piloting a Ford Mark IV, finished more than 30 miles ahead of the second-place Ferrari. It was the first (and, to date, only) all-American victory at the French endurance race – American drivers in an American car fielded by an American team. Gurney was so caught up in the excitement that he shook his celebratory champagne and sprayed it all over the crowd – the start of a victory tradition.

Just days after the 1967 Le Mans, Gurney earned yet another of his greatest victories when he won the Belgian Grand Prix in an Eagle car built by his own All American Racers. It was another singular achievement. To date, Gurney remains the only American driver to win a Formula One Grand Prix in a car of his own construction.

Dan Gurney retired from competitive driving in 1970, but remained active as a constructor and a team owner. His signature engineering achievement, the Gurney Flap, came in 1971. The small tab, added to the trailing edge of a spoiler or wing, increases downforce – and traction – on a car. Gurney flaps are found today not only on racing cars, but on helicopters and airplanes, too. In 1980, Gurney’s All American Racers built the first rolling-road wind tunnel in the United States. He introduced his low-slung Alligator motorcycle in 2002 and, ten years after that, the radical DeltaWing car, which boasted half the weight and half the drag of a conventional race car. Never one to settle down, Gurney and his team most recently were at work on a moment-canceling two-cylinder engine that promised smoother, more reliable operation than conventional power plants. Dan Gurney, 2008. THF56228

Dan Gurney, 2008. THF56228

Our admiration for Mr. Gurney at The Henry Ford is deep and longstanding. In 2014, he became only the second winner of our Edison-Ford Medal for Innovation. It was a fitting honor for a man who brought so much to motorsport, and who remains so indelibly tied to The Henry Ford’s automotive collection. Cars like the Ford Mark IV, the Mustang I, the Lotus-Ford, and even the 1968 Mercury Cougar XR7-G (which he endorsed for Ford, hence the “G” in the model name), all have direct links to Mr. Gurney.

We are so very grateful for the rich and enduring legacy Dan Gurney leaves behind. His spirit, determination and accomplishments will continue to inspire for generations to come.

Hear Mr. Gurney describe his career and accomplishments in his own words at our “Visionaries on Innovation” page here.

View the film made to honor Mr. Gurney at his Edison-Ford Medal ceremony below.

engineering, Mark IV, Indy 500, Le Mans, Europe, Indiana, California, New York, 21st century, 20th century, racing, race cars, race car drivers, in memoriam, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, cars, by Matt Anderson

The 1963 Mustang II: A Not-So-Missing Link

THF233334 / Advertising Process Photograph Showing the 1963 Ford Mustang II Concept Car.

The 1963 Mustang II (not to be confused with the Ford Pinto-based production Mustang II of the 1970s) surely is one of the most unusual concept cars ever built. Industry practice (and common sense) tells us that an automaker builds a concept car as a kind of far-out “dream car” to generate excitement at car shows. Most never go past the concept stage, but a few do make it into regular production. (Chevrolet’s Corvette and Dodge’s Viper are notable examples.) The Mustang II previewed the production Ford Mustang we all know and love, but the concept car was designed and built after the production Mustang project already was well underway! Why? It’s a case of managing public expectations.

Most Mustang histories start with the 1962 Mustang I, but devoted pony fans know that Mustang I was an entirely separate project from the production car. Ford built the “Mustang Experimental Sports Car” (its original name – the “I” was a retrospective addition) to spark interest in the company’s activities. Ford was going back into racing and looking for a quick way to create some buzz about the exciting things happening in Dearborn. The plan worked a bit too well. When Mustang I debuted at Watkins Glen in October 1962, and then hit the car show circuit, the public went crazy and sent countless letters to Ford begging the company to put the little two-seater into production.

At the same time Mustang I was being built, another team at Ford was working on the production Mustang that would debut in April 1964. Mustang I’s popularity created a problem: Everyone loved the two-seat race car, but would they feel the same about the four-seat version? The solution was to build a new four-seat prototype closely based on the production Mustang’s design.

Enter the 1963 Mustang II.

The new concept car wasn’t just based on the production Mustang’s design – it was actually built from a prototype production Mustang body. Ford designers removed the front and rear bumpers, altered the headlights and grille treatment, and fitted Mustang II with a removable roof. While the car looked different from the production Mustang, a few of the production car’s trademark styling cues were retained, including the C-shaped side sculpting and the tri-bar taillights. Mustang II also consciously borrowed from Mustang I, employing the 1962 car’s distinct white paint and blue racing stripes. Conceptually and physically, the four-seat Mustang II formed a bridge linking the 1962 Mustang I with the 1965 production car. Mustang II was a hit when it debuted at Watkins Glen in October 1963, and when the production version premiered six months later, there were few complaints about the four seats instead of two.

Fortunately, Mustang II is one “link” that isn’t “missing.” The Detroit Historical Society acquired the car in 1975 and has taken great care of it ever since.

View artifacts related to Mustang II in The Henry Ford’s Digital Collections.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, 20th century, 1960s, Mustangs, Ford Motor Company, convertibles, cars, by Matt Anderson