Posts Tagged by heather bruegl

The American Promise: The Speech that Changed a Movement

Selma is a sleepy little town in Alabama that has an extraordinary history. Located on the shores of the Alabama River in the heart of Dallas County, Selma is also home to the Jackson family.

Dr. Sullivan Jackson met Miss Richie Jean Sherrod at a family picnic the summer of her junior year in 1953. The meeting was brief, but Dr. Jackson was smitten, and he called Miss Sherrod the next day and asked her for a date. The two started dating steadily after that.

Dr. Sullivan and Richie Jean Jackson on their wedding day, March 15, 1958. / THF708474

While Richie Jean attended college in Montgomery, Sullivan would often drive over to see her, and they would go out to eat and spend time together. After Richie Jean graduated from college in 1954, the situation changed as both tried to navigate their worlds and have successful careers, and the two decided to end their relationship. But the universe had different plans. After a time, they were soon back together, and on March 15, 1958, they were married and began to create a life together that would shape their roles in civil rights and voting rights activism in ways they never imagined.

Dr. Sullivan and Richie Jean Jackson on their wedding day with family. / THF708475

It was March 1965, and many thought the fight for civil rights was over. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had been signed the year before, and many wrongs had been righted. However, the fight for equality and the right to vote was far from over. Things would reach a point where the president at the time, Lyndon Baines Johnson, would address Congress and demand something be done.

The movement for voting rights spread throughout the South in the United States, but its center was Selma, Alabama. In February 1965, a group of activists and protestors gathered outside Zion United Methodist Church in Marion, Alabama, about 26 miles northwest of Selma. One such protester was Jimmie Lee Jackson. Though they share a last name, he is not related to that Jackson family of Selma. He was at the protest with his mother, Viola Jackson, and his grandfather, Cager Lee. While trying to protect his mother from the escalation in violence, Jimmie Lee was shot twice in the stomach by Alabama State Trooper James Fowler. Eight days later, he died from his wounds.

The death of Jimmie Lee Jackson became one of the factors in the march from Selma to Montgomery for voting rights. The first attempt at this march resulted in Bloody Sunday on March 7, 1965. That event and the subsequent Turnaround Tuesday March on March 9, 1965, led to President Johnson giving one of the most powerful speeches in support of his presidency.

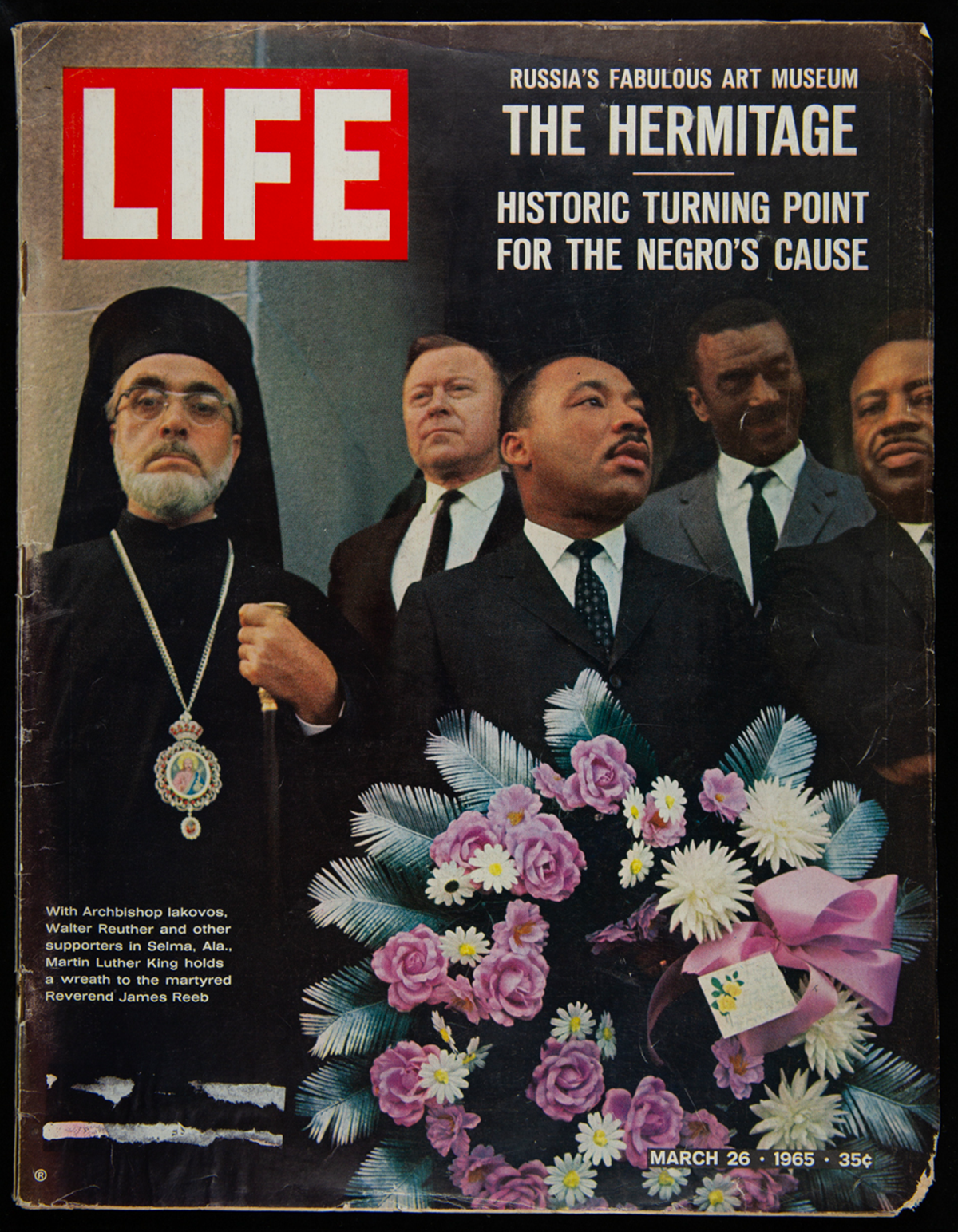

Life Magazine, dated March 26, 1965, discusses the Voting Rights Movement and President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s March 15, 1965, speech throwing his support behind the Voting Rights Act. / THF715927

It was March 15, 1965, when members of the Jackson family and guests gathered in their homes to listen to President Johnson give this speech. This was also the seventh wedding anniversary for “Sully” and Richie Jean. The President began:

“At times history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man's unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama.”

His words bring back memories of the American Revolution and the Civil War, two events in which the country fought for freedom. As the president continues with The American Promise speech, he brings up the death of Jimmie Lee Jackson while discussing the violence inflicted upon those who merely wish to register to vote.

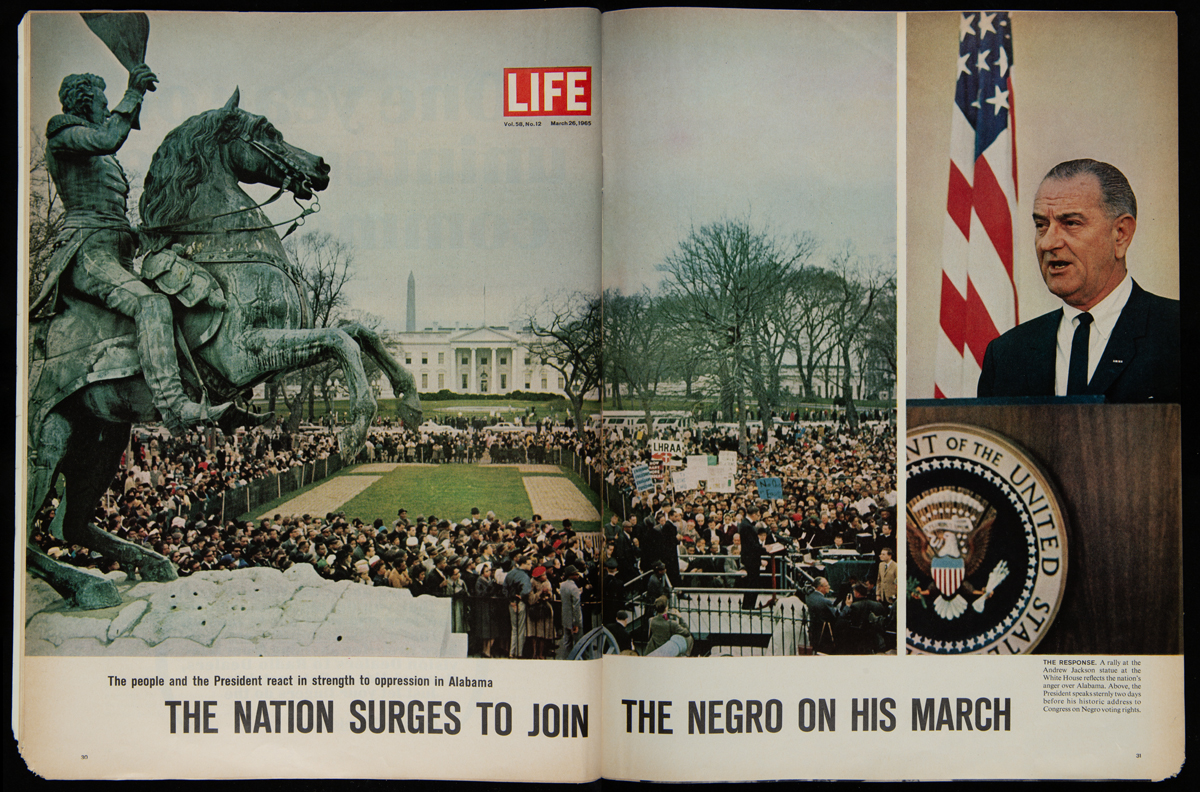

Life Magazine, dated March 26, 1965. / THF715929

The speech was written by writer and presidential advisor Richard Goodwin, who also worked for President John F. Kennedy. The President had decided on Sunday, March 14, that he would address the country the next night, March 15. Goodwin was assigned to write the speech at the last moment and had only eight hours to write. As a Jewish American, Goodwin pulled from his own experiences with anti-Semitic prejudice and discrimination.

The American Promise, more commonly known as the “We Shall Overcome” speech, hits on historic and contemporary moments leading to the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Invoking Patrick Henry’s famous “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” to the Declaration of Independence's statement that “All men are created equal,” the speech is the argument. It makes the case for a Voting Rights Act.

The President spoke about the barriers that had been put in place on Black Americans, from poll taxes to literacy tests, while also invoking the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, which guaranteed Black men the right to vote. This right was not always upheld.

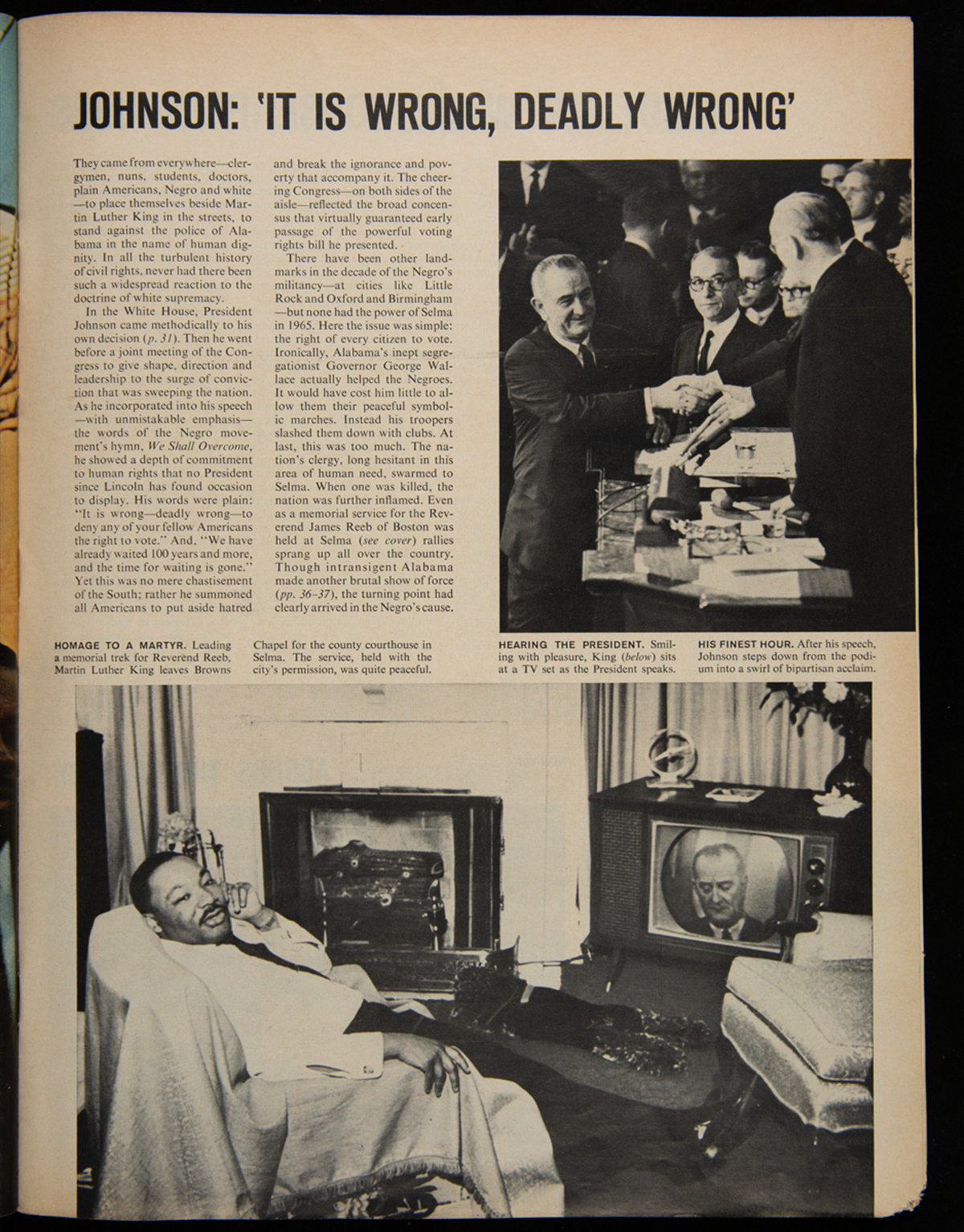

The speech was 48 minutes and 53 seconds long. Seventy million Americans watched it, including the Jackson family and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The White House received 1,436 telegrams of support and 82 telegrams against the idea of a Voting Rights Act, and LBJ was interrupted over 40 times for applause.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr watched President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s speech from the living room of the Jackson Home on March 15, 1965. Photo feature in Life Magazine, March 26, 1965. / THF715931

In his speech, the President discussed the need for the Voting Rights Act, his intention to push Congress to pass it, and how passing that act fulfills an American promise to all citizens to be able to vote for their leaders.

Pulling from a song that had become the anthem of the Civil Rights Movement, President Johnson signaled that he heard the activists working on the ground in Selma and would answer the call. And the speech that reiterated the American promise forever would be known by a different name: We Shall Overcome.

“Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.”

The full text of the speech can be found courtesy of The American Presidency Project.

A video excerpt of the speech can be found at the LBJ Presidential Library.

Heather Bruegl (Oneida/Stockbridge-Munsee) is the Curator of Political and Civic Engagement at The Henry Ford. This blog is part of a series exploring the history of the Jackson Home, opening in Greenfield Village, 2026.

On April 30, 1789, 235 years ago, in the nation’s first capital of New York, George Washington was sworn in as the first president of the newly formed United States of America. From that moment on, many aspects of Washington’s legacy would be built on myth, leaving out important parts of history that would help us understand the man and tell a fuller story. This isn’t to say that Washington didn’t do extraordinary things in his lifetime. Still, when we peel away the layers, we find that he was an ordinary man who lived in exceptional times and wasn’t as perfect as he is often portrayed.

Washington was born on February 22, 1732, on Popes Creek Plantation, (also known as Wakefield) in Westmoreland County, Virginia. In 1734, the Washington family moved to another property they owned, Little Hunting Creek Plantation, which was later renamed Mount Vernon. While Washington never received a formal education, he did have access to books and a private tutor. At the same time, he studied geometry and trigonometry on his own, for his first job as a surveyor.

Continue Reading