J.Edison Grain Sack: 2024 IMLS Conservation Feature

A team of staff from five departments at The Henry Ford have been busy during the final three weeks of an exciting IMLS grant project. Over the last two years of this grant-funded project (October 2022-August 2024), the efforts of conservation, collections management, cataloging, the photography studio, and curatorial, have led to the treatment and interpretation of 2,106 items stored in THF’s Collections Storage Building. Read on to explore behind-the-scenes work in the conservation lab!

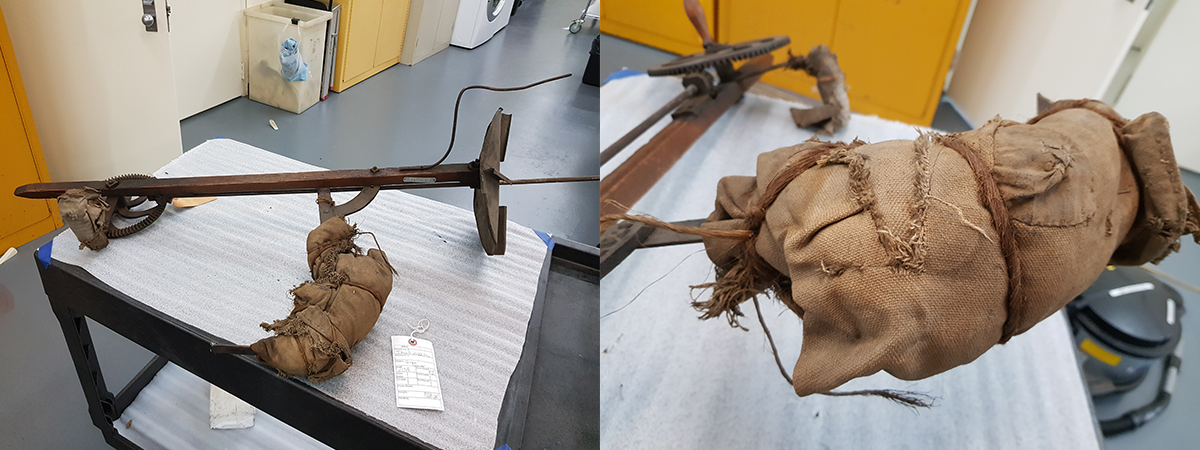

Broadcast Seeder with parts wrapped in fabric / Reference Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim) / 00.1384.23

This object might make you scratch your head, but it held clues that curators and cataloguers explored as conservators completed their work.

Conservation of the object started with a thoughtful study to determine next steps for treatment. This required unwrapping fabric and straw bound around two of the metal components. This was likely done by the donor to protect people from injuring themselves on the sharp metal while handling the object.

Grain Sack / Reference Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim) / 00.1384.23

One of the fabrics was a grain sack with the word “J.EDISION” stenciled in orange paint on the outside, front and back. The sack included torn areas that had previously been mended.

The level of dirtiness was first checked with wet paper and deionized water. Next, the bag was vacuumed to remove residual substances such as large pieces of dust and insect carcasses. During this process, we found a few grain seeds that were placed separately in a plastic bag for future research.

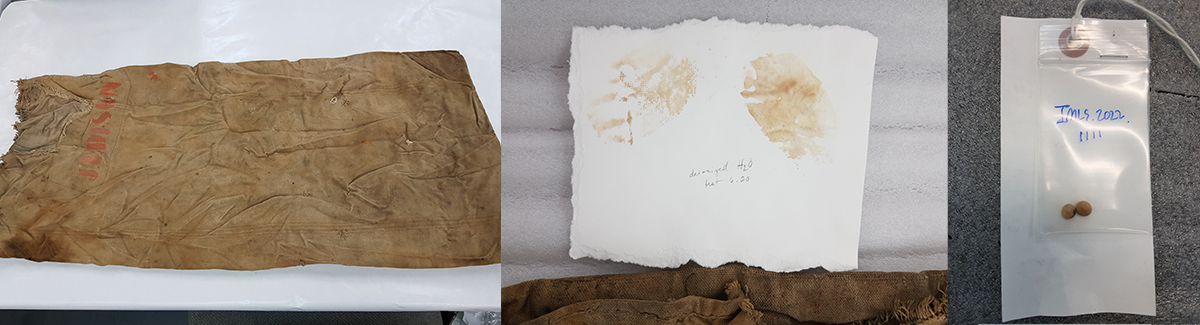

Grain Sack / Reference Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim) / 00.1384.23

After vacuuming, conservators worked with textile Conservation Specialist Katrina Herron to perform a wet cleaning. The bag was submerged in a tray filled with tap water. The bag was lightly agitated to remove dust and contaminants. The water was replaced and the process repeated until the water was clear enough to call the bag “clean.” While changing the water, the bag was rolled with a mesh sheet and set aside. This technique reduces the likelihood of damage to the bag when carried flat, as the weight of the water can cause too much tension to the fibers.

Grain Sack Treatment / Reference Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim) / 00.1384.23

The water was changed a total of fourteen times. At the beginning of the process, the dust and contaminants were removed with only tap water. The next cycles used tap water mixed with liquid soap. Orvus and Vulpex are gentle cleaners used by our conservation staff. In this project, they were used to clean the stains on the surface of the bag by pressing it with a soft sponge. In the end, deionized water was used to rinse out the soap thoroughly. Each time the water was replaced, a sample of the water was taken to determine the level of contamination.

Grain Sack before, during, and after treatment / Reference Images by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim) / 00.1384.23

After completing the wet cleaning process, the bag was left to air dry slowly on a mesh drying rack sandwiched between clean towels. The surface of the fabric is brighter after cleaning but still retains some stains that show its previous use.

As conservators treated the object, other members of the IMLS grant team explored additional clues to help with identification.

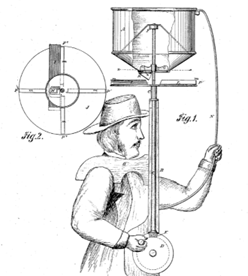

An attached tag reads: "GRAIN SOWER"/ "FROM: MR. + MRS. HAROLD EDISON"/ "GRAND RAPIDS." The description “Grain Sower” indicates that a farmer used the machine to sow wheat or other grains. Cranking the wooden handle turned a shaft topped with a flanged disc that broadcast the seed onto the field. An inscription on one of the cast metal components gave a patent date of March 22, 1870, and that led to U.S. Patent 101,136 for a “Broadcast Seeder.” The inventor, Jacob C. Kurtz of Wooster, Ohio, included illustrations with his patent, explaining that his device could rapidly and evenly distribute seed, and could also be adapted for use from a wagon.

Illustration from U.S. Patent 101,136, issued March 22, 1870 to J. C. Kurtz, Wooster, Ohio / United States Patent and Trademark Office

J.EDISON, UNPACKED

How did Mr. and Mrs. Harold O. Edison acquire this machine? The donors, likely Mr. Harold Ogden Edison and his wife Cosetta A. Hessey, did not explain this history, but the grain sack with “J.Edison” stenciled on it provided a critical clue. Harold descended from the family of Moses Edison (1783-1849). Moses had a son, John, who likely purchased the broadcast seeder and had the grain sack stenciled “J.Edison.”

In 1837, Moses, his wife Jane Saxton (1787-1872), and several children including John (1806-1889) moved from Vienna, Canada, to Walker Township, Kent County, Michigan (the Grand Rapids area). This date derives from a reminiscence shared when the Moses Edison family donated their spinning wheel to The Henry Ford (Wool Wheel, C. 1800-1830 / THF176591). They settled on land north of the Grand River, which was previously occupied by Ottawa (Odawa), Chippewa (Ojibwa), and Potawatomi (Bodewadi) peoples, who were required as part of the 1833 Treaty of Chicago to move to Kansas territory.

Did the Edison families in Walker Township have any connection to Thomas Alva Edison? Yes.

Moses was a brother of Samuel Ogden Edison (1767-1865) who was Thomas Alva Edison’s grandfather—which meant that Moses was Thomas Edison’s great uncle, and John (the owner of the grain sack) Edison’s first cousin once removed. In 1933, Thomas Edison’s homestead was sold to Henry Ford and moved to Greenfield Village. The broadcast seeder treated during the IMLS grant was located in the Edison Homestead as of 1951, confirmed by a small aluminum plate attached to its base (E.H.-382) during an inventory conducted in the house that year.

Thanks to funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, this broadcast seeder led to in-depth conservation treatment, while also prompting exploration of the stories connected to it, including removal, migration, agriculture, and familial connections over decades.

This blog was produced by Jeeeun Sims (Jee Eun Lim), Conservator, with Debra A. Reid, Curator, Agriculture and the Environment.

German Bread Recipe & Guide to Stoneware Bread Cloche Cooking

Our handcrafted and salt-glazed stoneware bread cloche allows you to mix your dough, proof it, and then bake it all in one dish. During the baking process, the lid traps steam, creating bread that is light and airy with a golden crust. Salt-glazed stoneware was a popular kitchen staple in the early 1800s as the firing process resulted in a surface that was both durable and beautiful.

German Bread Recipe

Ingredients:

- 1 pint bread sponge (To make a bread sponge, dissolve 2 tablespoons sugar and 1 teaspoon active dry yeast in 2 cups warm water)

- 1 cup sugar

- 1 egg

- 3 tablespoons melted butter

- 4 cups flour (Keep an additional 1 to 2 cups on hand as needed)

Directions:

- 1. Beat together the bread sponge, sugar, egg and butter until you have a light mixture.

- 2. Stir in flour until the mixture is thick. Begin with 4 cups and then add 1-2 additional cups as needed.

- 3. Grease interior sections of the bread cloche and pour in the mixture.

- 4. Cover the cloche and let the dough rise until it doubles in size (roughly about an hour).

- 5. Open the cloche and punch the dough down.

- 6. Re-cover the cloche and let the dough rise a second time (about 30 to 45 minutes).

- 7. Bake covered in a moderate oven (350 F for 25 to 30 minutes).

This recipe and cooking technique are demonstrated onsite at Firestone Farm in Greenfield Village.

Source: The Household of the Detroit Free Press, 1881, p. 386; edited for modern use by The Henry Ford Living History Leadership.

In August 1924—one hundred years ago—an interplanetary celestial event between Earth and Mars became an opportunity for speculation, scientific study, and inspiration. Every 26 months or so, our planet aligns in “opposition” with Mars, reducing our distance from around 140 million miles to 34.6 million miles. But not all oppositions are equal. Since Earth and Mars have elliptical orbits, every 15-17 years the distance during an opposition becomes even shorter. The view, more clear. A distance scale of millions of miles described as being “close by” is unfathomable to many of us. Still, these special “perihelion” oppositions have served as an essential time for astronomers to observe Mars and test their theories. The 1924 Mars opposition from August 22-24 was one of these special “perihelion” examples.

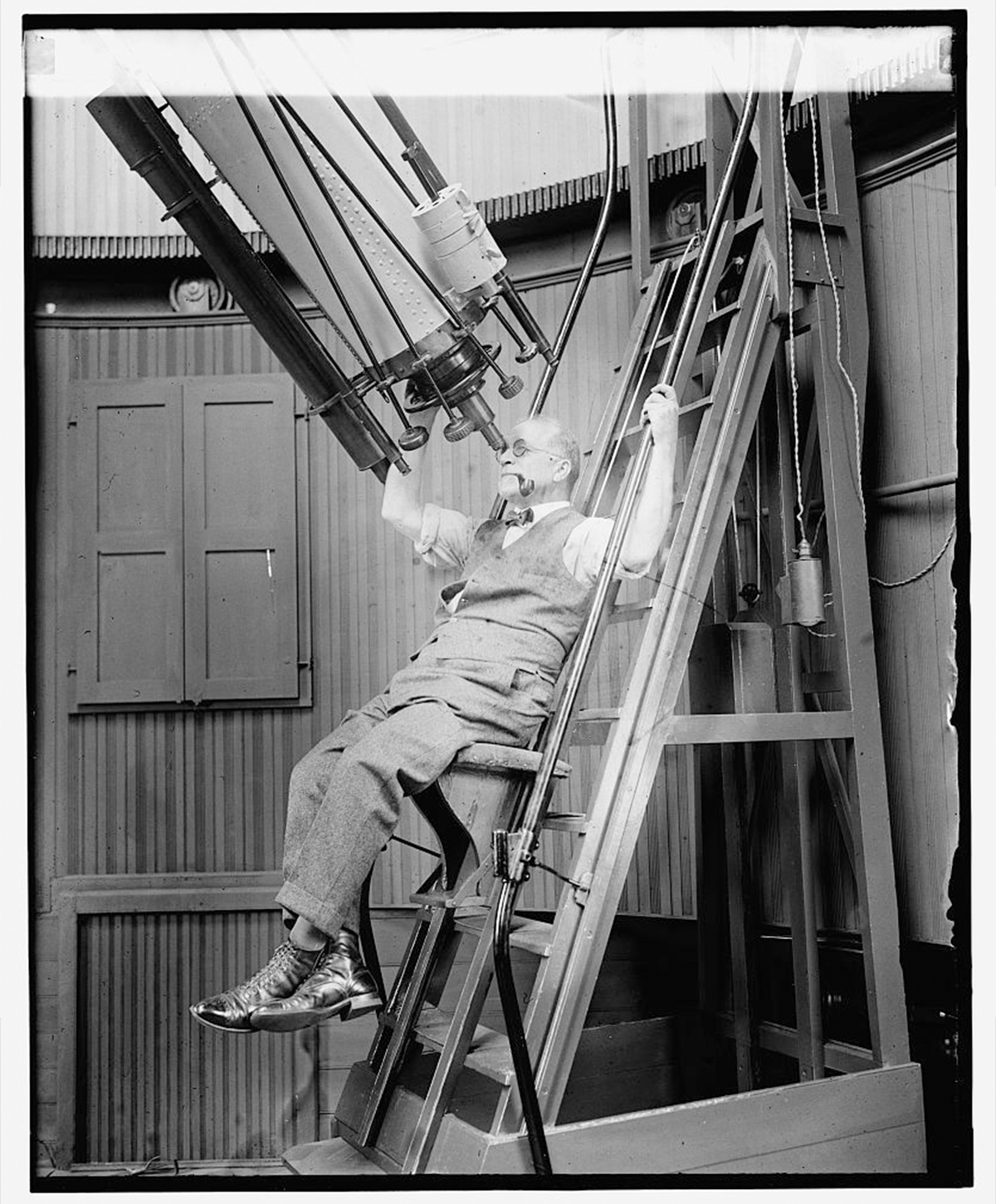

Astronomer and Mars enthusiast David Peck Todd looks through a telescope at Georgetown University Observatory, 21 August 1924 / Courtesy of National Photo Company Collection (Library of Congress)

During this time of celestial wonder, an ambitious and strange experiment occurred: an attempt to “listen” for signs of life emanating from the Red Planet. While this experiment may seem fitting in a science fiction novel, it was supported by the U.S. military and the U.S. Weather Bureau. The Army and Navy collaborated with astronomer David Peck Todd and engineer Charles Francis Jenkins as the project's leads, with the assistance of cryptographer William Friedman.

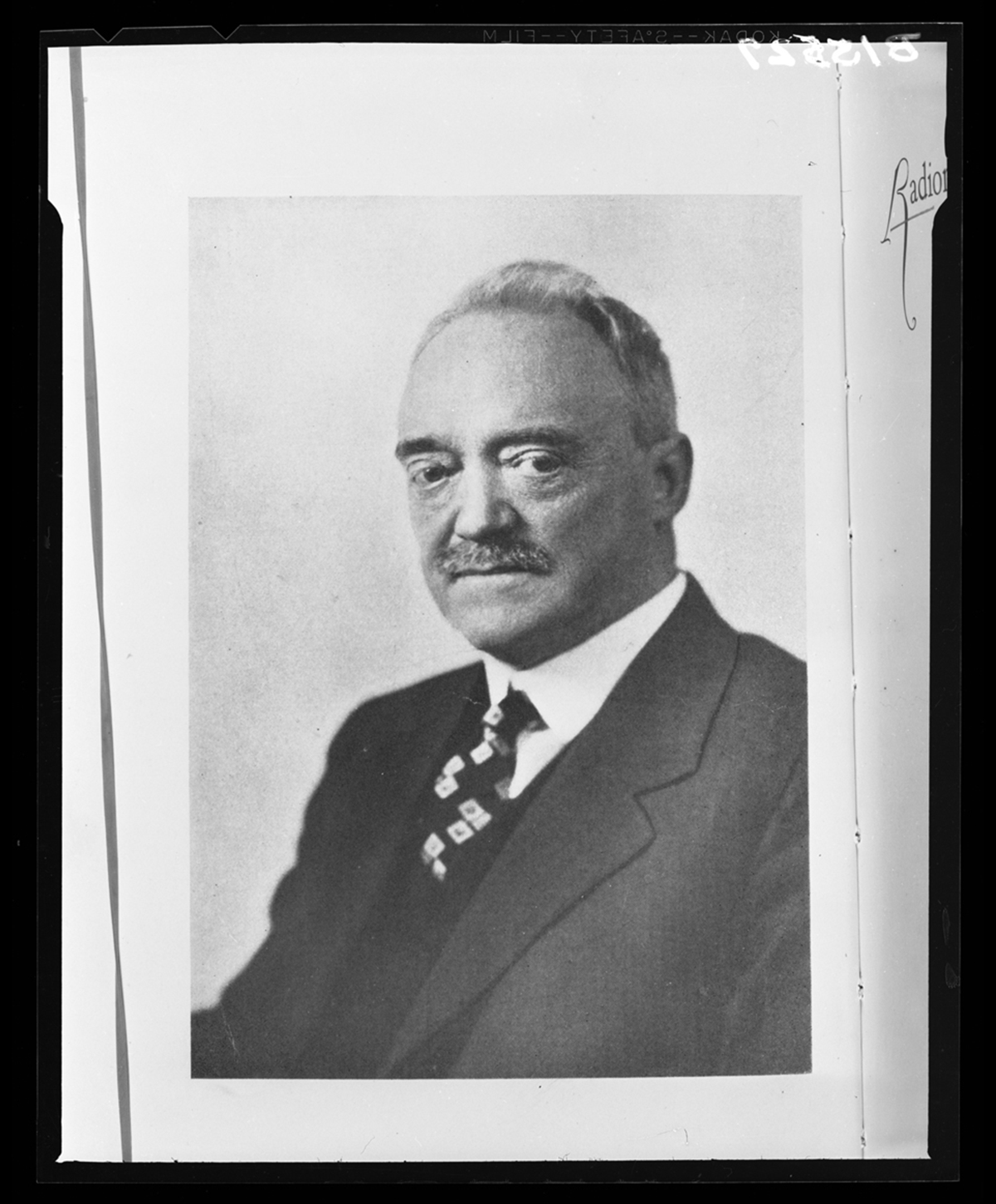

Portrait of Charles Francis Jenkins, c. 1925 / THF120578

Charles Francis Jenkins was an inventor who worked in early cinema and television technology from the 1890s into the 1930s. Many of his experimental devices used radio wave technologies to transmit and record images over long distances. While Jenkins was eager to test new reaches for his inventions across state lines, he definitely wasn’t aiming for transmission at a deep space level.

David Peck Todd was an accomplished astronomer and the former observatory director at Amherst College in Massachusetts. In 1882, he became the first person to photograph Venus's transit and later became fascinated with the “intelligent planet” theories of 19th-century astronomers Percival Lowell, Giovanni Schiaparelli, and Camille Flammarion. Todd was fascinated with the "canals of Mars" theory, which claimed that the lines crisscrossing the surface of the planet—observed by Todd and others through telescopes—were Martian-made irrigation canals. In reality, these lines proved to be an optical illusion caused by telescope lenses of the time, but the hope remained for Todd. Seeking to achieve extraterrestrial communication, Todd convinced the military to cooperate with his plan to harness the 1924 opposition as an ideal time to gather “signals from Mars.”

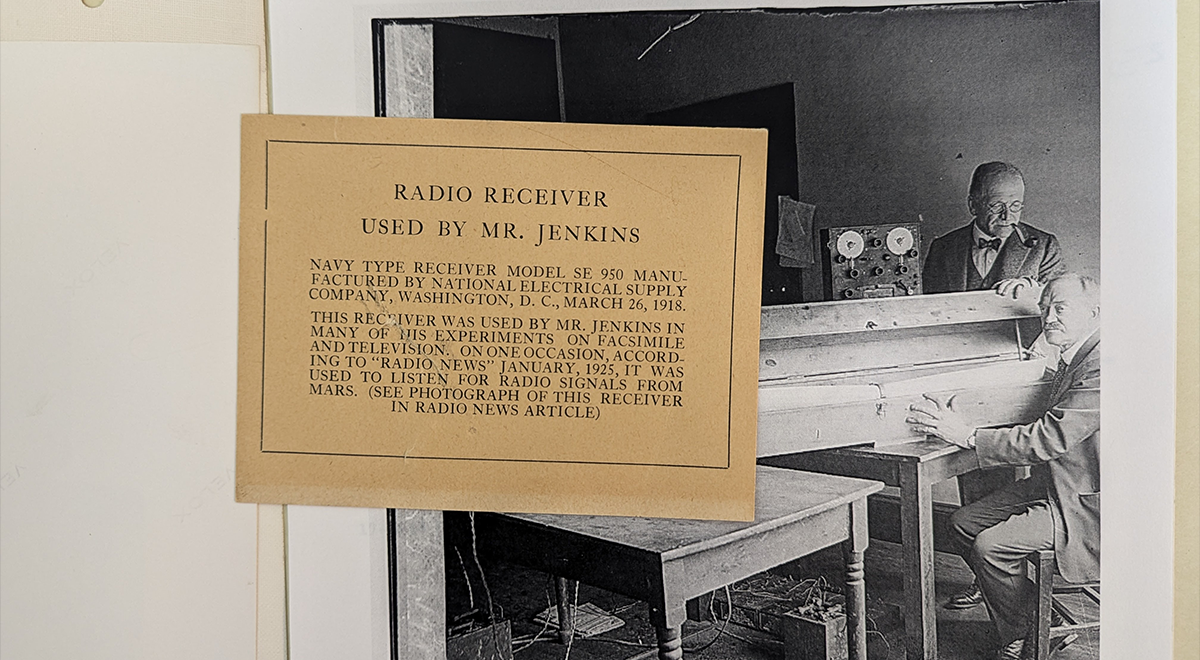

Label from a former exhibit at The Henry Ford with details about Jenkins’ SE-950 radio. The radio is visible in the image above, to the left of Todd (standing). Jenkins is seated with another component of the Jenkins Radio Camera / Image by Kristen Gallerneaux

The short version of this story is that during the peak of the Mars opposition, on August 22-24, the military would request periods of radio silence each day—any rogue signals that bled through Jenkins’ and Todd’s equipment could, in theory, prove the existence of life on Mars. On the ground, the devices used to “listen” for signals were Jenkins’ “radio photo message continuous transmission machine” (more simply, the Jenkins Radio Camera) and a SE-950 NESCO radio. If any signals were detected, they would be translated into flashes of light, exposing static-like forms onto a 30-foot long piece of photographic paper fed onto spools in the wooden box seen in the image above.

Radio Receiver, Type SE-950, used by Charles Francis Jenkins in experiment detecting radio signals from Mars / THF156814

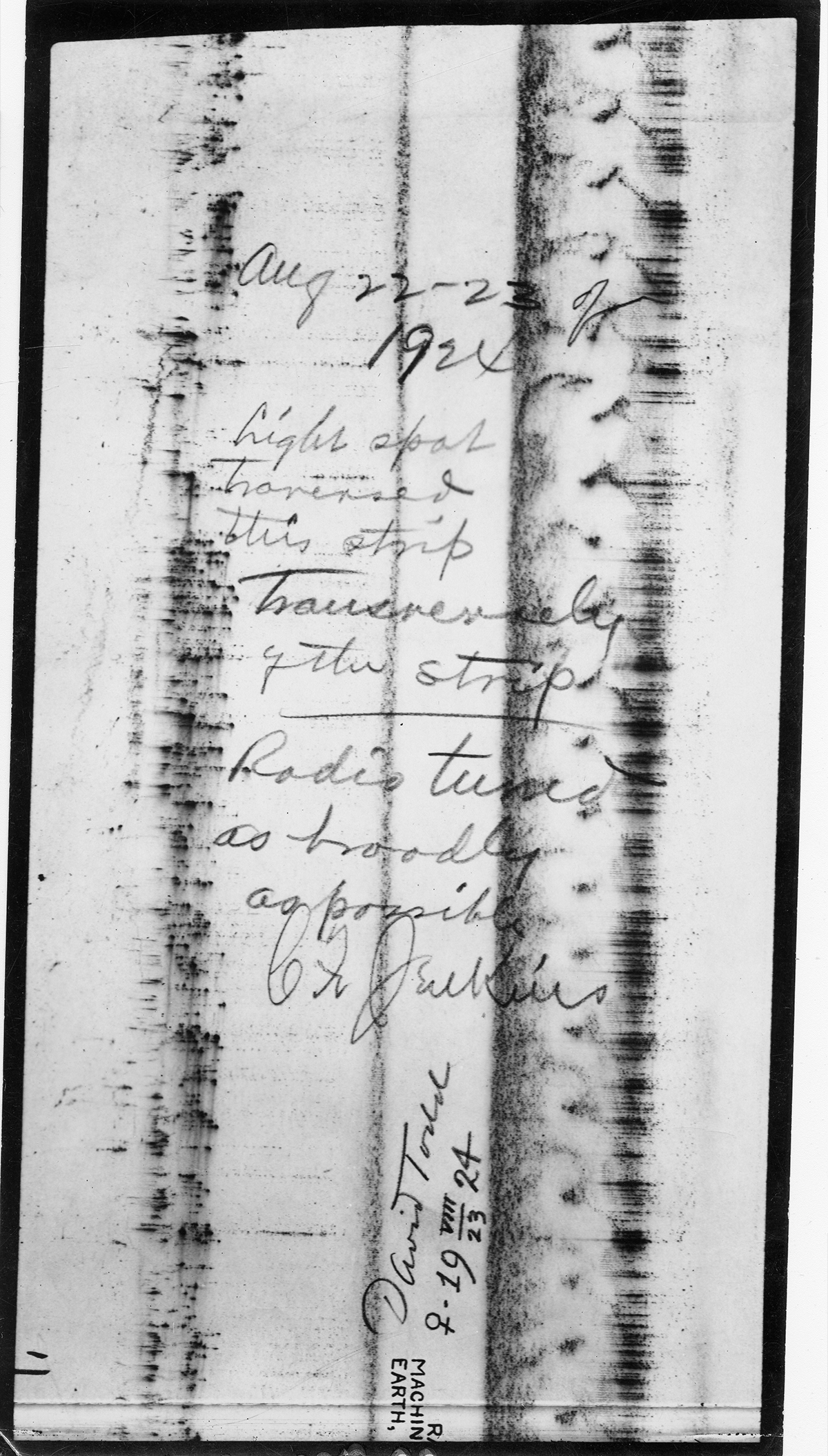

For his part, Jenkins was skeptical and tried to distance himself from Todd’s belief to protect his reputation as a scientist. Throughout the experiment, static did filter through the Jenkins Radio Camera. William Friedman, the cryptographer, could not make sense of it. The public interpreted these signals visually, believing they were seeing the form of a human face in the static. The fervor quickly died down when it became obvious that the interference was likely caused by radio heterodyning, from passing trolley cars, or even the natural radio waves of Jupiter.

Radio signals collected during the 1924 Mars opposition by Todd and Jenkins using the “radio photo message continuous transmission machine” / Courtesy of Yale University Archives, David Peck Todd papers

The Henry Ford’s collections contain many of Jenkins’ prototypes and experimental technologies that he used in his laboratories, which came to us in 1940 through Jenkins’ widow, Grace Love Jenkins. What remains of Jenkins' apparatus used during the 1924 Mars opposition? In this curious stretch of three days, technology was pushed beyond what it was ever intended to do. This SE-950 radio is a poetic conduit in communication history—and believed to be the last remaining three-dimensional object used in the experiment. The rest of the Jenkins Radio Camera is believed to be lost, although the photographs of the messages received during August 1924 are located in the Yale University Archives.

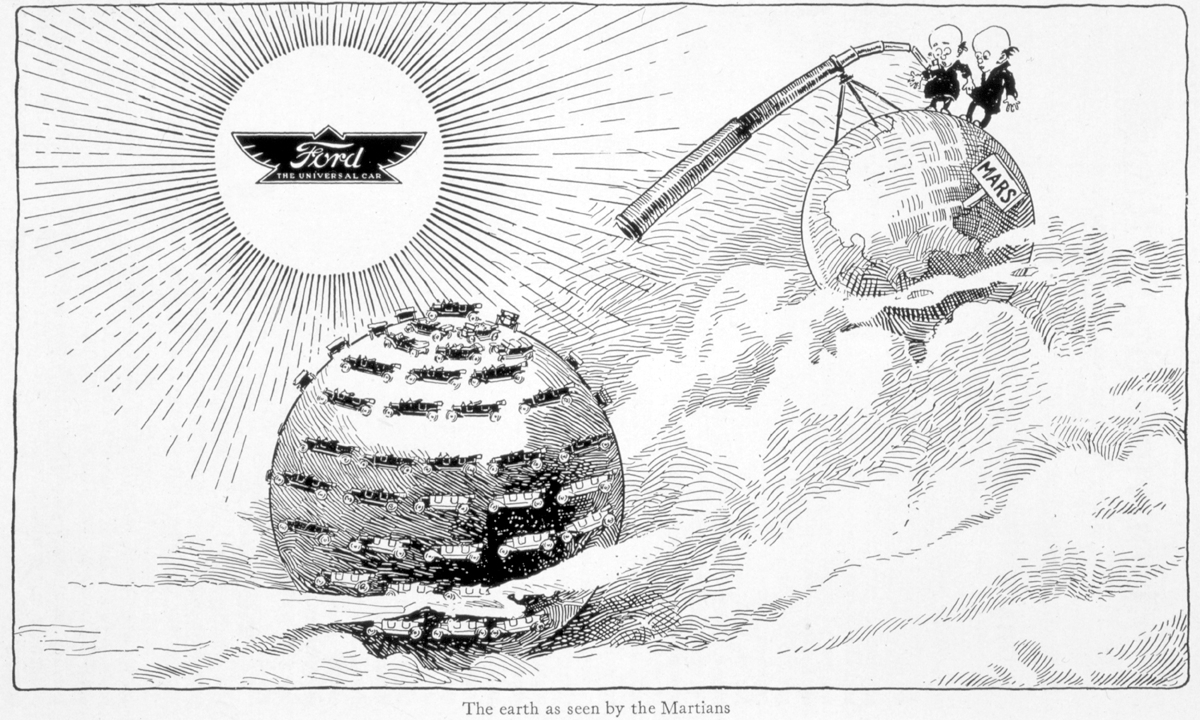

Illustration from the December 1913 issue of Ford Times, predating the 1924 Mars opposition. What if the tables were turned, with Mars observing Earth? / THF3205

This experiment is often cited as part of the lineage that led to the formation of organizations like the SETI Institute, which employs scientific experts to search for intelligent life in the universe. A century later, the events of August 1924—reported on, rediscovered, and recently rediscovered once again as we near the 100th anniversary—continue to find new audiences. Celestial events like solar eclipses, comets, and meteor showers inspire people to seek out collective moments of awe-inspiring wonder, sometimes travelling long distances for the best view of these fleeting moments. Readers who can relate might broaden their celestial horizons to consider the history of public and scientific fascination with Mars, which will be in opposition to Earth in January 2025, February 2027, and March 2029. For the next extra special “perihelion” opposition, akin to the one that happened in 1924 though? You’ll need to wait a little longer, until 2035.

Kristen Gallerneaux is curator of communications & information technology and the editor-in-chief of digital curation.

Hairstyling and Homemaking: The Career of Velma Truant

In 2023, The Henry Ford acquired a remarkable collection — a hair dryer and salon chair, in fabulous mid-century pink and chrome, as well as the tools, pins, rollers, and documents that hairstylist Velma Truant had collected over her nearly forty-year career. The collection serves as detailed documentation of Velma’s career, balanced with her home life as a wife and mother.

Velma Truant at the Illinois state line during her honeymoon, about 1950 / THF712578

Velma was born in Hungary to Steven and Suzannah Toth, on Christmas Day 1928. Shortly after Velma’s birth, the family immigrated to the United States, settling in Detroit’s Delray neighborhood — an area popular with Hungarian and other Eastern European immigrants who had come to Detroit looking for opportunity and well-paying jobs. Steven worked as a musician in a Hungarian band until his death when Velma was eleven, while Suzannah worked in the kitchen at the Book Cadillac hotel — a job that allowed her to bring home extra food to sustain her family during the Great Depression. Beginning at age fourteen, and while still attending school, Velma worked a series of jobs, including at a candy store and a funeral home.

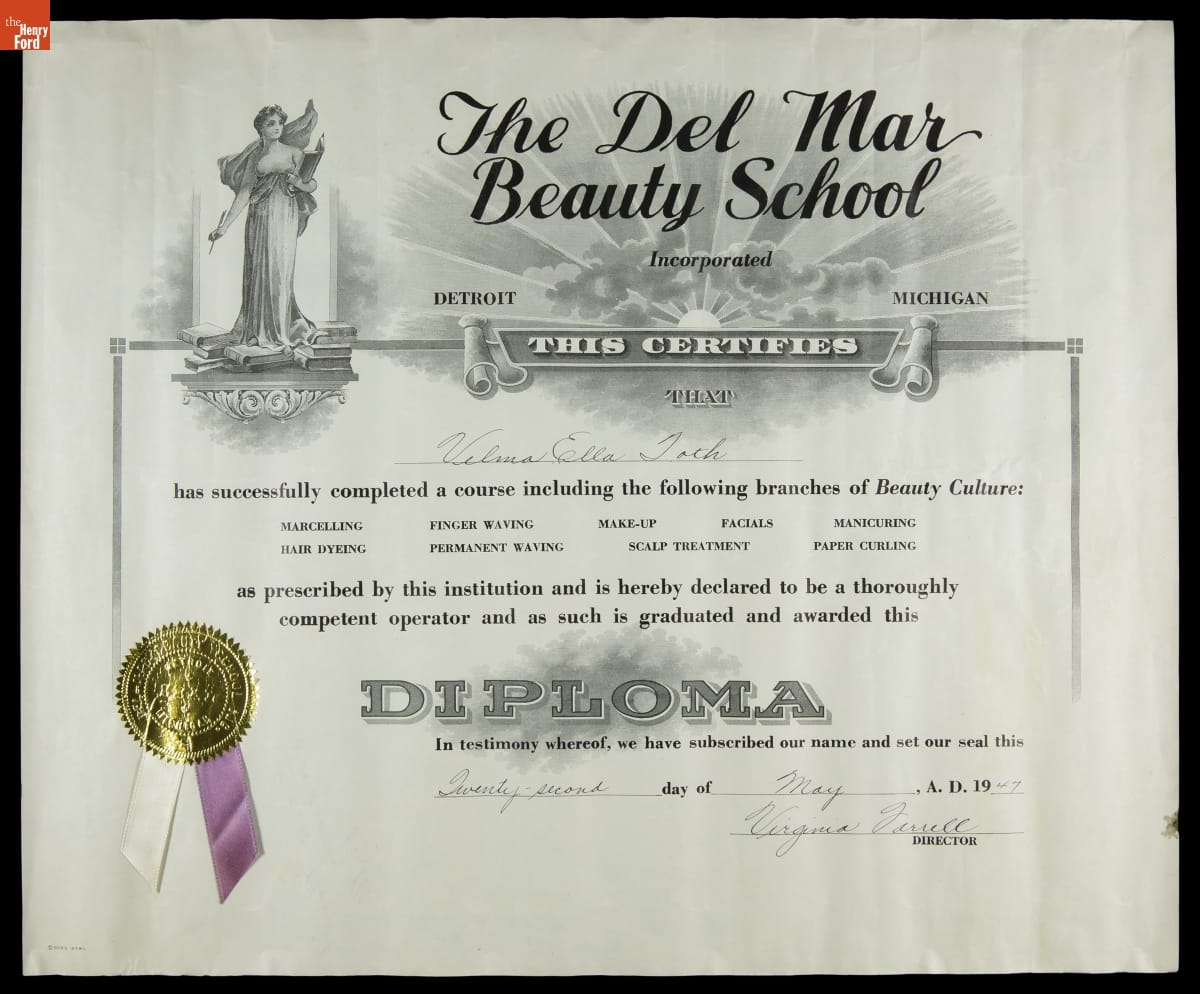

After graduating from Southwestern High School in 1946, Velma initially began taking engineering and design classes at Wayne State University. She changed her plans, however, and decided to enroll at the Del-Mar Beauty School in Detroit to begin training to become a hairstylist. By February 1948, twenty year old Velma was styling hair at the J. L. Hudson department store (commonly known as Hudson’s) in downtown Detroit. In 1950, Velma married Aldo Truant, the son of Italian immigrants. The couple first lived with Aldo’s parents in the Oakwood Heights neighborhood of Detroit, before building their own home in Allen Park. Even after marriage, Velma continued to work at Hudson’s, as she enjoyed earning her own money.

The Del-Mar Beauty School, Inc. Diploma Awarded to Velma Ella Toth, 1947 / THF714037

By the time Velma worked there in the early 1950s, Hudson's was the second-largest department store in the country — second only to Macy’s — and the tallest store in the world with thrity-two floors. The downtown building housed 200 departments on forty-nine acres of shopping floor space, employed 12,000 people, and averaged 100,000 customers per day. At its peak in the late 1940s through the early 1960s, it offered a circulating library, a writing lounge, dry cleaning, shoeshine, travel services, typing lessons, interior design consultation, home advice, hat cleaning, and jewelry repair. Its beauty salon had existed since at least the 1920s, and in 1947 was updated to include 17,000 square feet and 160 employees, offering facials, complexion consultation, makeup services, and permanent wave machines, in addition to traditional hairstyling. Velma would have been busy, as she worked in an era when many women made frequent trips to the beauty parlor.

Velma Truant (front row, far left) and other Hudson’s hairstylists, 1962 / THF712587

While working at Hudson’s, Velma frequently traveled to New York City to receive training at the American Hair Design Institute, where they taught new techniques and the latest fashions. Velma loved these trips, and was often joined by Aldo. On one notable trip to New York, Velma was asked to work with Lucille Ball; as a natural strawberry blonde, Velma understood how to work with red hair. Velma took great pride in her work. While she liked the glamour and social aspect of the salon, she herself was never too “into the beauty thing,” as her daughter recalled. She always had immaculate nails and dressed meticulously, but never used much makeup.

Velma Truant working on mannequin hair in New York / THF712584

In August 1963, Aldo and Velma — who had struggled for years to conceive a child — adopted a baby girl, whom they named Cynthia after Velma’s boss at Hudson’s. That same year, Velma made the choice to leave Hudson’s to devote more time to caring for her daughter. She did, however, continue to take clients in her home salon, set up in her basement laundry room. Once Cynthia settled into elementary school in 1970, Velma returned to work with Hudson’s, transferring to the Southland branch in July. In December, she was promoted to manager. The promotion, however, changed the way Velma felt about her work, and she retired from Hudson’s in 1972.

Hair dryer and salon chair from Velma Truant’s in-home salon, likely acquired when Hudson’s updated their Northland location in 1960s / THF370815, THF370816

During her brief return to Hudson’s, Velma continued seeing clients in her home. She worked from her basement salon throughout Cynthia’s school years, only fully retiring from hairstyling in 1981.

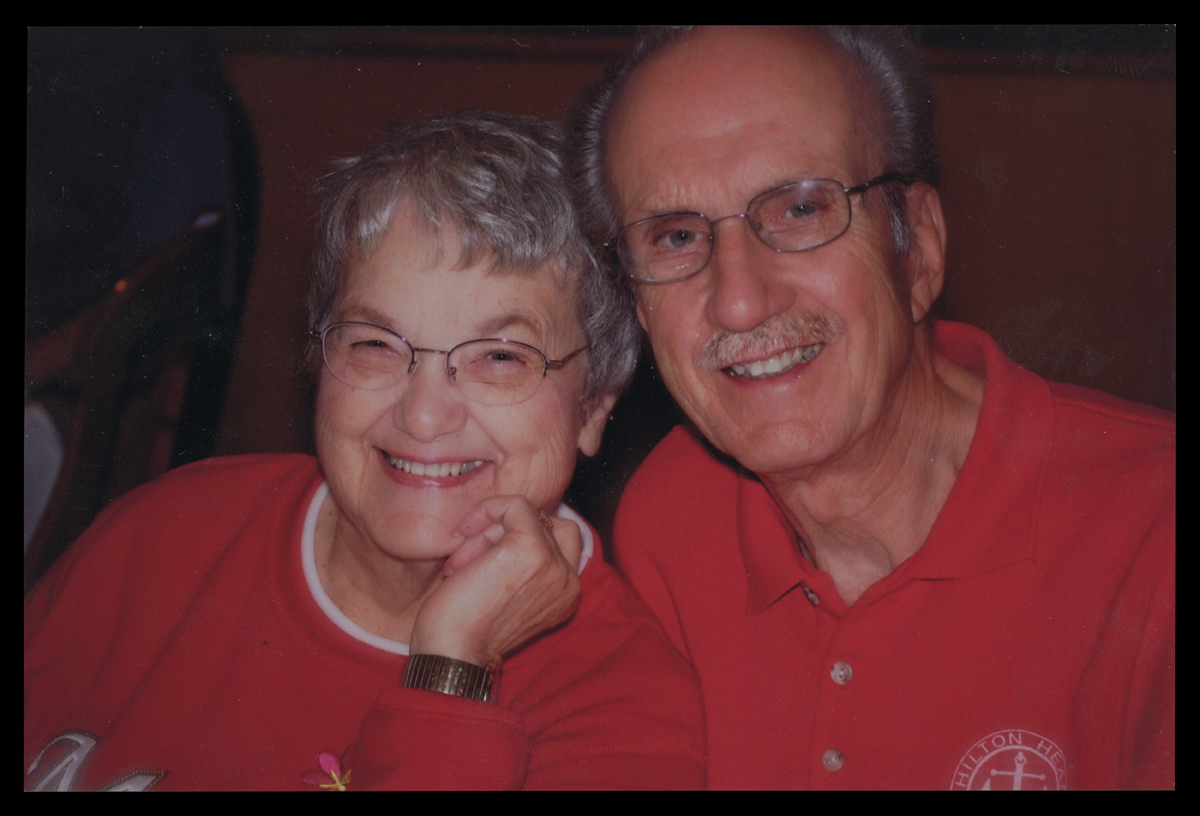

While the artifacts themselves document Velma Truant’s work as a hairstylist, the reminiscences provided by her family further tell a story about who she was as a person. Her daughter, Cynthia, recalls that Velma was “always immaculate,” both in her personal attire and in the presentation of her home — even going so far as to keep a stock of green toilet paper to match her salmon-and-green basement bathroom. Velma and Aldo would often dress in matching colors, and remained close until his death in 2018, after 67 years of marriage. Velma herself would pass away in November 2021, leaving behind a legacy as not just a talented hairstylist, but a devoted wife and mother.

Velma and Aldo Truant at Portofino’s restaurant, Wyandotte, Michigan, July 2009 / THF712591

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an associate curator at The Henry Ford.

With gratitude to Saige Jedele, who conducted the original research for this acquisition.

Masterpiece of Motion

Our carousel exposed: a simple mechanism with lots of pizzazz

Each week Jacob Hildebrandt, manager, historic operating machinery, climbs atop Greenfield Village's Herschell-Spillman Carousel to properly lubricate its gears and fittings. During the season, the Henry Ford staff also do daily safety inspections of the carousel, listening for squeaks and grinding noises, inspecting for loose boards and bolts, putting pressure on every animal and many other checks. / Photo by EE Berger

In this blog, we examine what's at the heart of the carousel — the inner workings that keep the ride in motion and the staff that maintains its motor, gears and bearings so thousands of visitors can go round and round and up and down each year.

Today, a 10-horsepower electric motor runs the carousel. In 1913 when the ride was built, it was likely run by an early Westinghouse electric motor, said Jacob Hildebrandt, manager, historic operating machinery.

A fairly simple machine, the carousel's motor turns a vertical drive shaft that runs up to the crown of the ride. The rotation of that shaft then rotates a large ring gear at the top that turns the carousel round.

“It's like twirling an umbrella,” said Hildebrandt. “All the power comes from the middle and spreads out.”

The carousel's electric motor is connected to a gearbox with an electric brake and torque converter similar to a vehicle so the motor can run before the carousel begins to spin, avoiding jerky, sudden movements. The brake can bring the ride to a complete stop within two revolutions.

Radiating from the middle are smaller crankshafts with bevel gears, which is what the carousel's moving animals hang from. The rotation of these shafts and gears — and therefore the up-and-down motion of the animals — is powered by the carousel's spin.

Marc Greuther, vice president, historical resources and chief curator, who has intimate knowledge of the underbelly of the carousel, likens the transfer of power from a shaft on a vertical axis to a set of undulating animals on a platform as “a quiet masterpiece of motion."

To keep this masterpiece in motion, Hildebrandt, one other full-time employee and a part-time staffer are on-site daily climbing about the ride lubricating its gears and fittings. “Functionally, the grease we use is one of the most modern things about the carousel today,” he said.

The carousel is equipped with highly durable Babbitt-style bearings, added Hildebrandt, rather than the now more common ball bearings. In the early days, these bearings and the carousel's gears would have been lubricated with a less-viscous oil, which is much messier and ephemeral than the grease now used — which “sticks to everything,” said Hildebrandt.

While some of the carousel's larger gears have worn and been replaced over the years, for the most part its internal hardware remains original. “It's a fairly straightforward mechanism underneath the skin,” said Greuther. “An application of very, very practical machinery that's the result of innovation and applications in industry.”

Jennifer Laforce, managing editor, The Henry Ford Magazine

The Scrap Book Habit

Life is made up of thousands and thousands of little bits and pieces. Many of these pieces of our lives are special to us or hold value in one way or another and therefore we tend to find creative ways to hang onto them. Whether they be recipes on the back of food packaging, a poem, a picture in a magazine, a beautiful message on a greeting card, all these little scraps are what some may deem worthy of pasting into a book to be memorialized together. These little ‘scraps’ of life, once put together with intention, become scrapbooks.

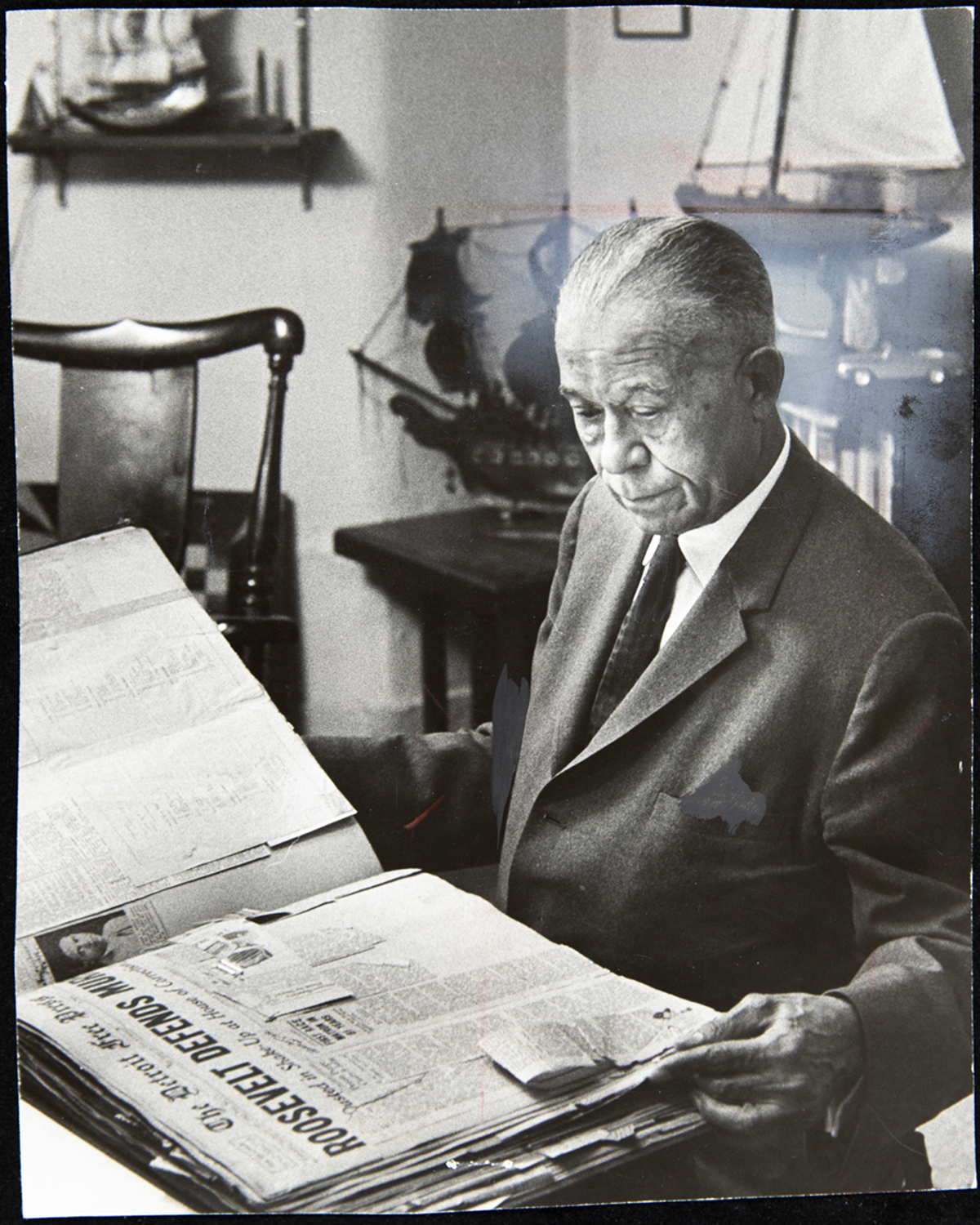

John C. Dancy, Executive Director of the Detroit Urban League, looking through a scrapbook, May 1966 / THF620105

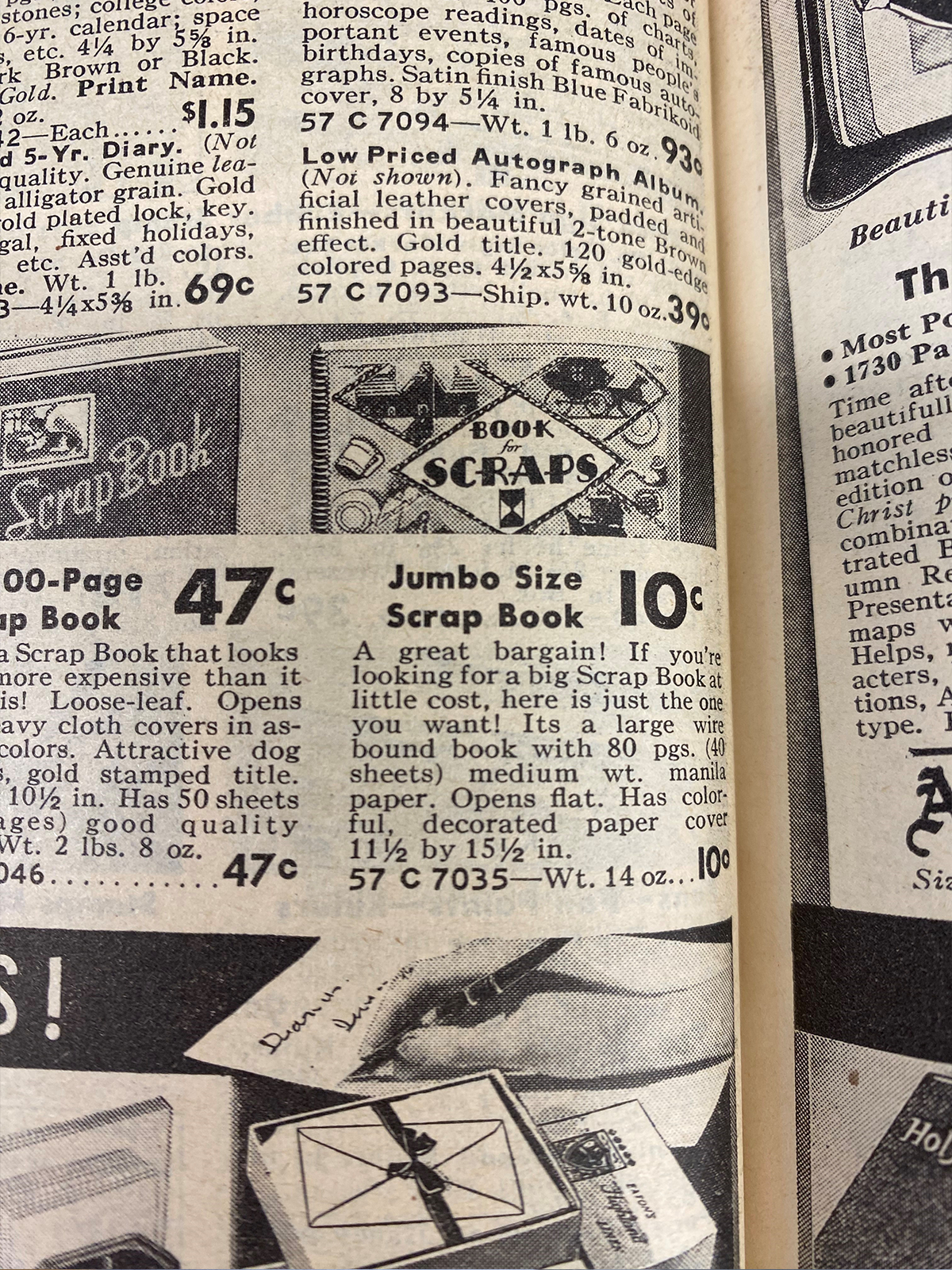

Often blurring the lines between photo albums and journals, this craft typically takes the form of collecting paper items and selectively deciding what will be adhered into a blank book, where it will be placed, and why. Although it has taken different forms until reaching what we think of as a scrapbook today, this craft has been practiced for hundreds of years progressing hand in hand with the timeline of printing technology and availability of commercial goods.The widespread availability of scrapbook supplies from the 20th century and beyond proves that the books are still a popular means of expressing our personal wishes to capture parts of life.

Advertisement for a ready-made blank scrapbook, Montgomery Ward 1938 catalog. P.B. 1938 / Image by Mollie Gordier

Just like their subject, scrapbook creators vary greatly as well. Housewives, children, businessmen, scientists, and so on have gotten into the “scrap book habit.” The Henry Ford is fortunate to have a wide-ranging collection of scrapbooks showcasing this diversity. Following are some examples.

Eva Tanguay, a vaudeville actress who took the country by storm, wished to document the newspaper clippings highlighting her performances at the American Music Hall in Chicago, Illinois, on May 18-31, 1913. As public coverage of her work was important to her, even the criticisms made their way into this memory capsule.

Cover of a scrapbook made by Eva Tanguay. 2005.100, Box 9 / Image by Mollie Gordier

World's Fairs were monumental events where people could experience new innovations, art, and the grandeur of architectural structures from around the world. For the 1939 New York World’s Fair, two Edison Institute teachers and their wives were sent along with students to the event for the summer. Hazel June Ebel, the wife of one teacher, compiled some memorable pictures of that experience.

Page from a scrapbook compiled by Hazel June Ebel, 1939 / THF245988

Other scrapbooks aspired to capture momentous periods in time, such as the one created by Montgomery City Lines bus company supervisor, Charles “Homer” Cummings. Cummings went about compiling newspaper articles detailing the first few months of the Montgomery bus boycott that was sparked by Rosa Parks and her refusal to give up her bus seat in 1955.

Page from the Montgomery Bus Boycott Scrapbook created by Charles H. (Homer) Cummings, November 1955-April 1957 / THF147439

Travel adventures were also exciting subjects to include in a scrapbook, particularly travel by automobile. This opportunity for rugged independence was gaining plenty of steam by the 1920s as more people purchased automobiles and roads became less like bumpy paths. This 1938 scrapbook showcases mementos documenting restaurants eaten at, hotels stayed in, routes taken, postcards collected, and movies seen.

Page from a travel log of an automobile round trip from Saginaw, Michigan, to Miami, Florida, January 21-February 27, 1938 / THF240831

Scrapbooking is not only for the individual. Companies and organizations also partook in this craft, using it for product design, business documentation and recordkeeping. As is the case with the Heinz company, where they wanted to document some of the various food items they produced by creating a scrapbook with some of their early twentieth century product labels.

Page from a Heinz scrapbook containing Heinz product labels, 1900-1930 / THF293440

While many scrapbooks have an individualized touch or are completely improvisational, commercially constructed scrapbooks made with prompts ready to be filled out by the user were also available. Such as this 1999 “Nickellennium” scrapbook created for the television channel Nickelodeon to document the global lived experience of young people bringing in a new millennium. This book provided sections with questions or open-ended sentences for people to record what their lives were like at the moment while also envisioning what life would look like in the future. As an extra bonus, this scrapbook was produced in conjunction with a 5-hour world-broadcast documentary that aired for 24 hours on January 1, 2000 to document what young people all over the world had to say about what a Y2K era would bring.

Pages from the Nickellennium scrapbook. 808.883 O32 1999. / Image by Mollie Gordier

With technological advances, scrapbook forms have transformed as well. One example is audio scrapbooks, such as this one containing various recordings of Ernie Harwell’s time as a baseball announcer from 1948 to 2002. Another example would be the entirely digital scrapbooks now available through online companies.

Inside case view of Ernie Harwell’s Audio Scrapbook. 796.357 H343 2006 CD. / Image by Mollie Gordier

While providing people a way to record physical materials and their significance, scrapbooking historically has also been a way to build communal experiences. There have been scrapbook contests, international school classroom scrapbook exchanges, scrapbooks made for organizations, and even stores dedicated to scrapbook supplies and learning.

Overall, whether crayons and construction paper were used or a store-bought book had ornate Victorian advertisements of cats dancing pasted throughout, scrapbooks have had a long and varied existence.

One of many decorative advertisements within a scrapbook created by Carree O’Keefe, circa 1895. 58.7.29. / Image by Mollie Gordier

For more information on the scrapbook material or any of our other collections, please reach out to the staff of the Benson Ford Research Center at research.center@thehenryford.org

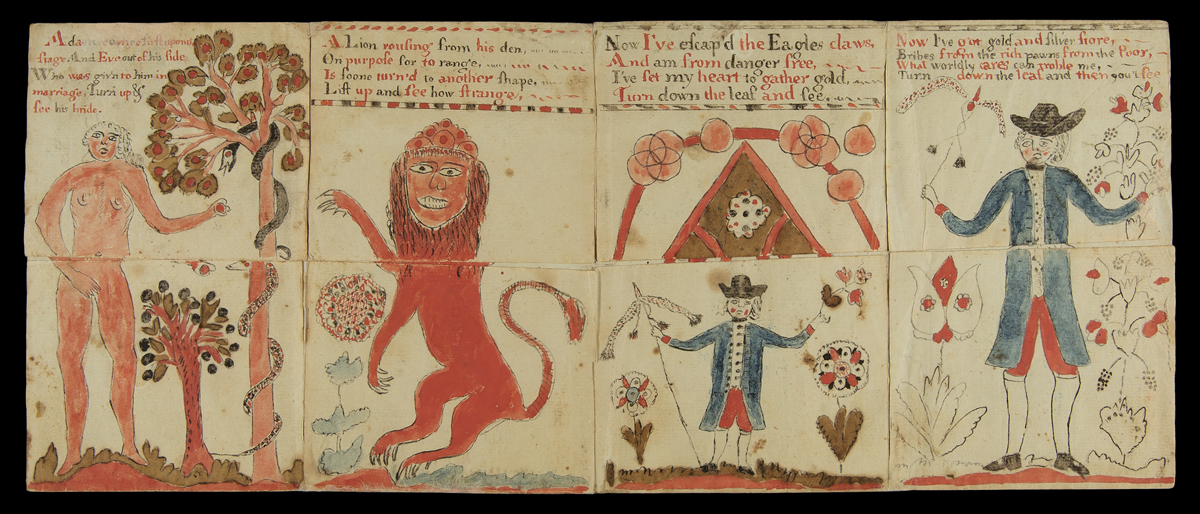

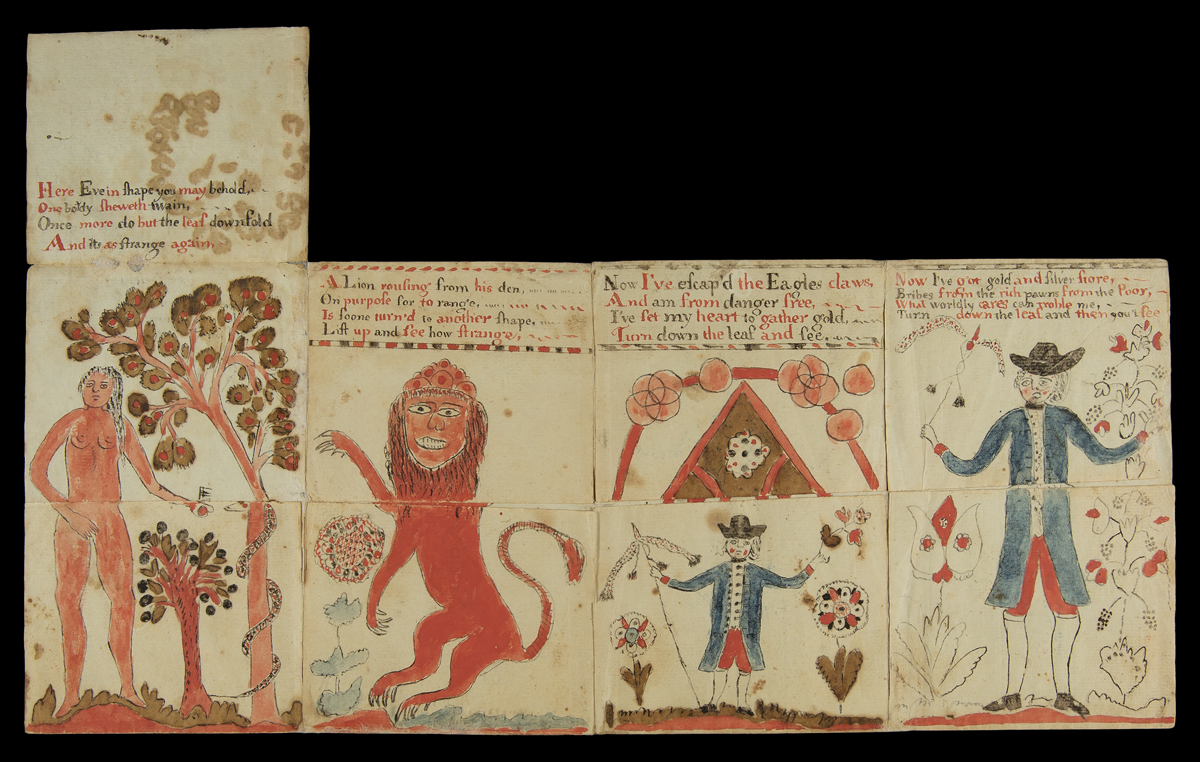

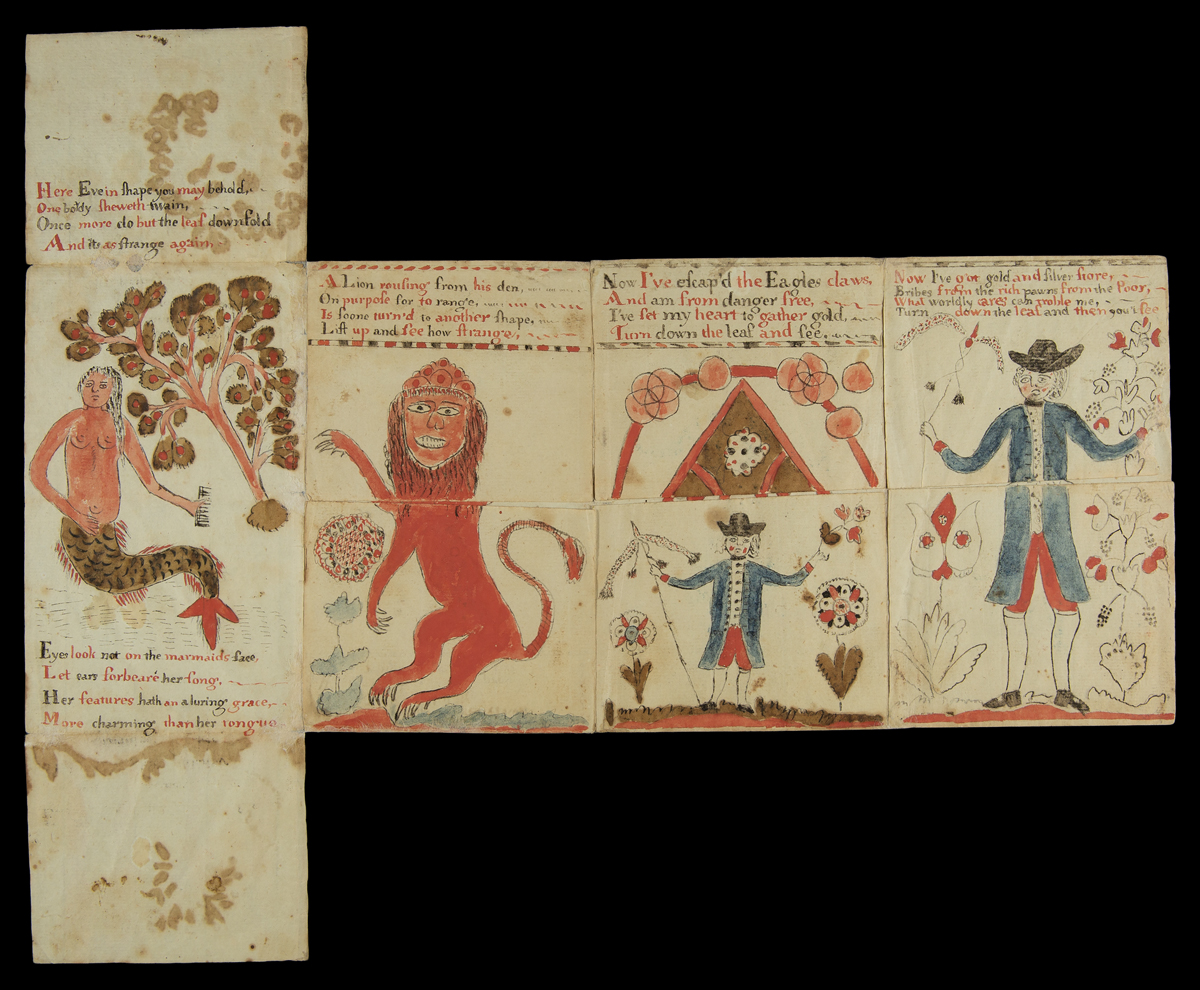

Metamorphosis Turn-Up Book, 1790-1820 / THF715860

Boxed and tucked away for many years in the Benson Ford Research Center archives at The Henry Ford, this turn-up book has found a new life — a metamorphosis — much like its title. This "book" — a sheet of cut and folded paper — engaged the reader in tactile learning and instilled moral lessons in interactive ways, conveying lessons and meaning through visual images and texts that change with the lift of a flap.

Movable and Turn-up Books

For hundreds of years, artists, illustrators, publishers, designers, and paper engineers have added motion and 3-dimensional depth to the flat pages of books and other paper-based media. Early examples of movable books date to the thirteenth century and involved the use of volvelles — a movable paper disk or wheel — and flaps. Designed as teaching tools for adult learners, scholars of science, religion, and philosophy manipulated these movable elements to predict astronomical events, plot yearly spiritual holidays, teach anatomy and other medical disciplines, and aid navigation, among other uses.

Eighteenth-century transformations in childhood education from strict rote learning to a more active model made movable books an appealing option for teaching children. By the mid- to late 18th century, publishers began selling printed flap or turn-up books for a wider readership that included adults and children. These sheets of cut and folded paper lured readers to interact with its pages filled with stimulating images and poetic texts that changed when readers lifted or folded down flaps. In the United States, printed versions of Metamorphosis or A Transformation of Pictures with Poetical Explanations for the Amusement of Young Persons presented a series of moral tales on movable pages and, as the title states, were directed toward a younger audience.

Metamorphosis

Metamorphosis or A Transformation of Pictures with Poetical Explanations for the Amusement of Young Persons traces its origins to earlier turn-ups such as the mid-1600s English publication The Beginning, Progress and End of Man. These early turn-ups instilled religious and moral lessons (and perhaps exposed political preferences as well) through images and verse — aspects that later authors copied, modified, and recontextualized in printed and handmade versions.

The Henry Ford's handmade version of Metamorphosis or A Transformation of Pictures consists of four panels and dates from the late 18th or early 19th century. Each panel contains two intersecting flaps; one turns up, the other down. Panels transform not once but twice, imparting moral lessons through religious, mythological, and heraldic iconography and poetic texts. First, Adam in the Garden of Eden changes to Eve — who then transforms into a mermaid. Next, a lion transforms into a mythical griffin and finally into an eagle, grasping a young child to carry him off. The third panel depicts the grown child as a young man eager to make money no matter the cost. The last panel shows what awaits the man who follows such a path: disease and death.

The first panel shows Adam in the Garden of Eden. The verse begins:

Adam comes first upon the

stage And Eve out of his side

Who was giv'n to him in

marriage, Turn up &

See his bride.

As the reader lifts the flap to reveal Eve, the verse continues:

Here Eve in shape you may behold,

One body sheweth twain

Once more do but the leaf downfold

And its [sic] as strange again,

Next, the reader turns down the flap to reveal a "marmaid," as the verse concludes:

Eyes look not on the marmaids [sic] face,

Let ears forbeare [sic] her song.

Her features hath an aluring [sic] grace,

More charming than her tongue.

It is unfortunate that the artist and owner histories of this Metamorphosis turn-up book have been lost. Similar handmade versions from the early 1700s to the late 1800s in other library collections exist, with only some including an artist's name. These examples have been an invaluable source for researching our copy. Curators at The Henry Ford — examining the book's form, texts, and imagery, including stylistic clues in the man's dress and the ornamentation on the later panels — believe this turn-up book may have been made in Pennsylvania, sometime between 1790 and the first decades of the 1800s.

Speculation continues about the artistic origins of this book. Was this made by a young woman as part of her education, promoting art and writing skills that would aid her later in life, or was this something a new mother crafted for her children to reinforce moral lessons? What we do know is that this once-hidden gem is part of a larger collection of turn-up books scattered in museums and libraries across the nation that may shed light on the beliefs, educational practices, and life of Americans in the early years of the republic.

Resources

For more information and to see other turn-up books like the one in the collection of The Henry Ford, see the following:

"Learning as Play: An Animated, Interactive Archive of 17th- to 19th- Century Narrative Media for and by Children." The Pennsylvania State University, 2019. https://sites.psu.edu/play/

Sperling, Juliet. "Unfolding Metamorphosis, or the Early American Tactile Image." American Art, 35, (3) 58-87. 2021.

Reid-Walsh, Jacqueline. "Format and Meaning-Making in Religious Turn-Up Books: The Remediation of The Beginning, Progress and End of Man into Metamorphosis, or a Transformation of Pictures: With Poetical Explanations for the Amusement of Children." [Chapter 10] in Forms, Formats and the Circulation of Knowledge: British Printscape's Innovations, 1688-1832. Ed. by Louisiane Ferlier and Bénédicte Miyamoto. (Library of the Written Word, 83; The Handpress World, 64.) Leiden and Boston: Brill. 2020.

Andy Stupperich is an associate curator at The Henry Ford.

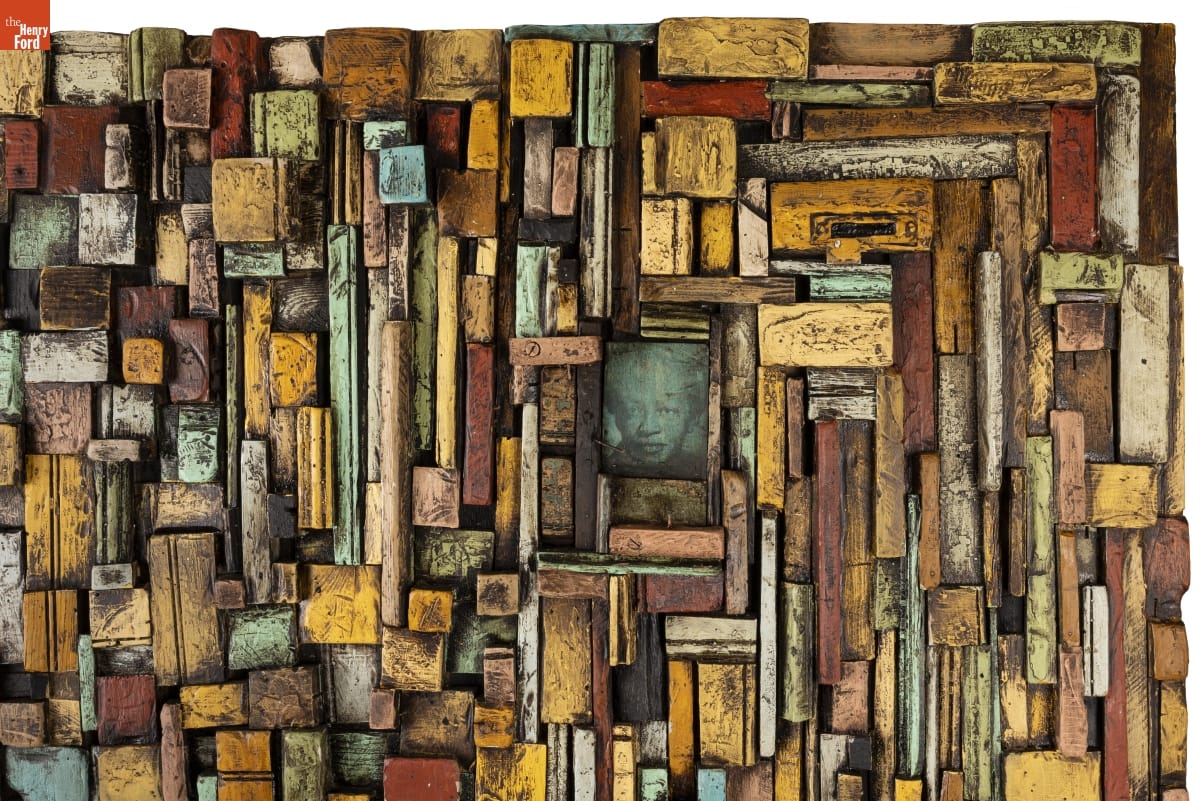

A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama

In 2023, The Henry Ford acquired an incredible piece of art: a wooden sculpture by New Orleans artist Jean-Marcel St. Jacques, entitled “A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama.” The wooden quilt weaves together many threads from both St. Jacques's own family history and the stories already told in the institution's collections.

"A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama" by Jean-Marcel St. Jacques, 2023 / THF197819

"A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama" by Jean-Marcel St. Jacques, 2023 / THF197819

Jean-Marcel St. Jacques is a twelfth-generation Louisiana Afro-Creole. In the 1970s, his family left Louisiana for California, hoping to escape the racial oppression they faced in the South. Looking to reconnect with his family's roots, in 2004, St. Jacques moved back to the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans, purchasing a former boarding house that had been owned by a woman known to the community as Mother Sister. One year later, however, Hurricane Katrina ravaged the Gulf Coast, particularly New Orleans. St. Jacques's home, along with many others, was severely damaged.

St. Jacques describes how the storm became a defining moment in his life, writing: “The last decade and a half of my life and work has been defined by the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The force of nature that blew the roof off of my house and forced me into a silent meditation and communication with my ancestors.” Using wood and other architectural fragments he salvaged after the disaster, St. Jacques began creating sculptural wooden art pieces -- doors, wall hangings, and his larger “quilts” — piecing together fragments and hardware, adding vibrant colors, and weaving in references to his family history. His great-grandmother Laura Agnew had been a quiltmaker, while his great-grandfather had been a junk man, gathering and reselling pieces he found, as well as a hoodoo man, practicing syncretic spirit work. St. Jacques considers his workshop to be “an ancestor shrine,” and keeps his great-grandmother's quilts and great-grandfather's tools nearby as he works.

Detail from "A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama,'' featuring a portrait of Laura Agnew, the artist's great-grandmother / THF197824

Detail from "A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama,'' featuring a portrait of Laura Agnew, the artist's great-grandmother / THF197824

While every one of his pieces honors his family history, St. Jacques wanted this piece to be a special tribute to his great-grandmother, whom he called “Big Mama.” Amongst the hardware and painted wood blocks that make up the piece, there is a printed portrait of her tucked in the upper right-hand quadrant.

St. Jacques's wooden quilt not only connects to his great-grandmother's quilting practice, but to the practice of other quilters already represented in The Henry Ford's collections — particularly the work of quiltmaker Susana Allen Hunter.

Susana Hunter lived in Wilcox County, an impoverished, rural area of Alabama. She was an improvisational quilter, making up her quilt designs as she went along, often using material taken from clothing and fabric she and her family used, as well as material given to her by others. The quilt below features fabric that likely came from the clothing her husband Julius wore as a tenant farmer — denim overalls and flannel shirts — and is backed with material from mule feed sacks. The quilt not only reflects Hunter's improvisation and creativity, but also captures the history of her family through the physical material — much like St. Jacques's wooden quilt.

Strip Quilt Made of Work Clothes by Susana Allen Hunter, 1965-1970 / THF73636

Strip Quilt Made of Work Clothes by Susana Allen Hunter, 1965-1970 / THF73636

Acquiring this wooden quilt continues The Henry Ford's long tradition of collecting American folk art. Henry Ford's personal interest in what we would today consider folk art created the foundation for a collection that now stands at nearly 2,000 pieces, and includes works by such noted artists as George Washington Mark (1795-1879), Ammi Phillips (1788-1865), and William Matthew Prior (1806-1873). St. Jacques's work further enriches this collection, updating and diversifying it in a way that honors the folk art tradition.

"Opening the Door," considered painter George Washington Mark's masterpiece, is one of the highlights of The Henry Ford's folk art collection. / THF172048

"Opening the Door," considered painter George Washington Mark's masterpiece, is one of the highlights of The Henry Ford's folk art collection. / THF172048

Every object in The Henry Ford's collection tells a story about past lives, be it directly via pieces connected to specific individuals, or more generally with objects that demonstrate life in different time periods. It is a special honor to be the institutional home for a piece like “A Wooden Quilt for Big Mama” — a piece that honors the life of the artist, his family, and his community — and to share with the public the rich stories it holds.

Rachel Yerke-Osgood is an associate curator at The Henry Ford.

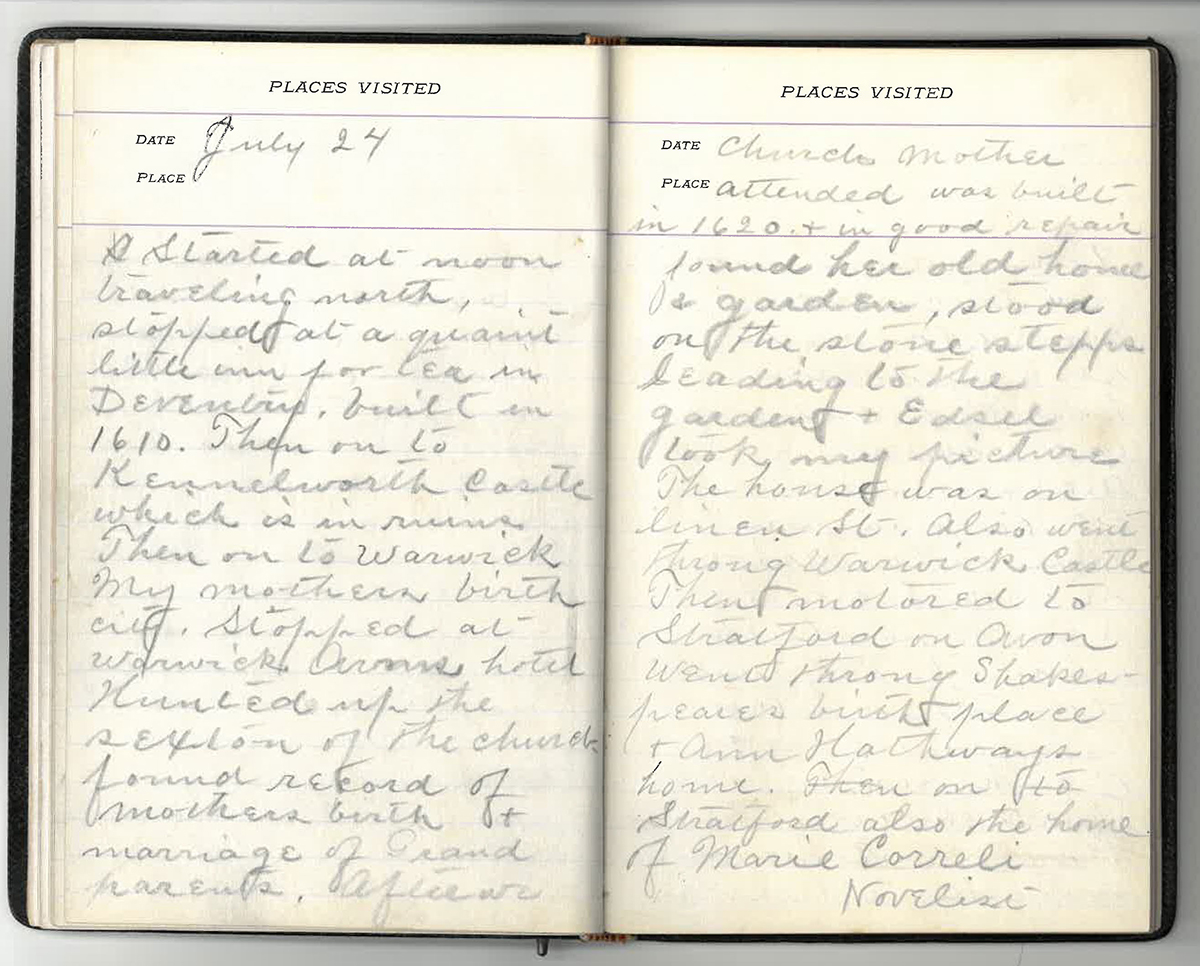

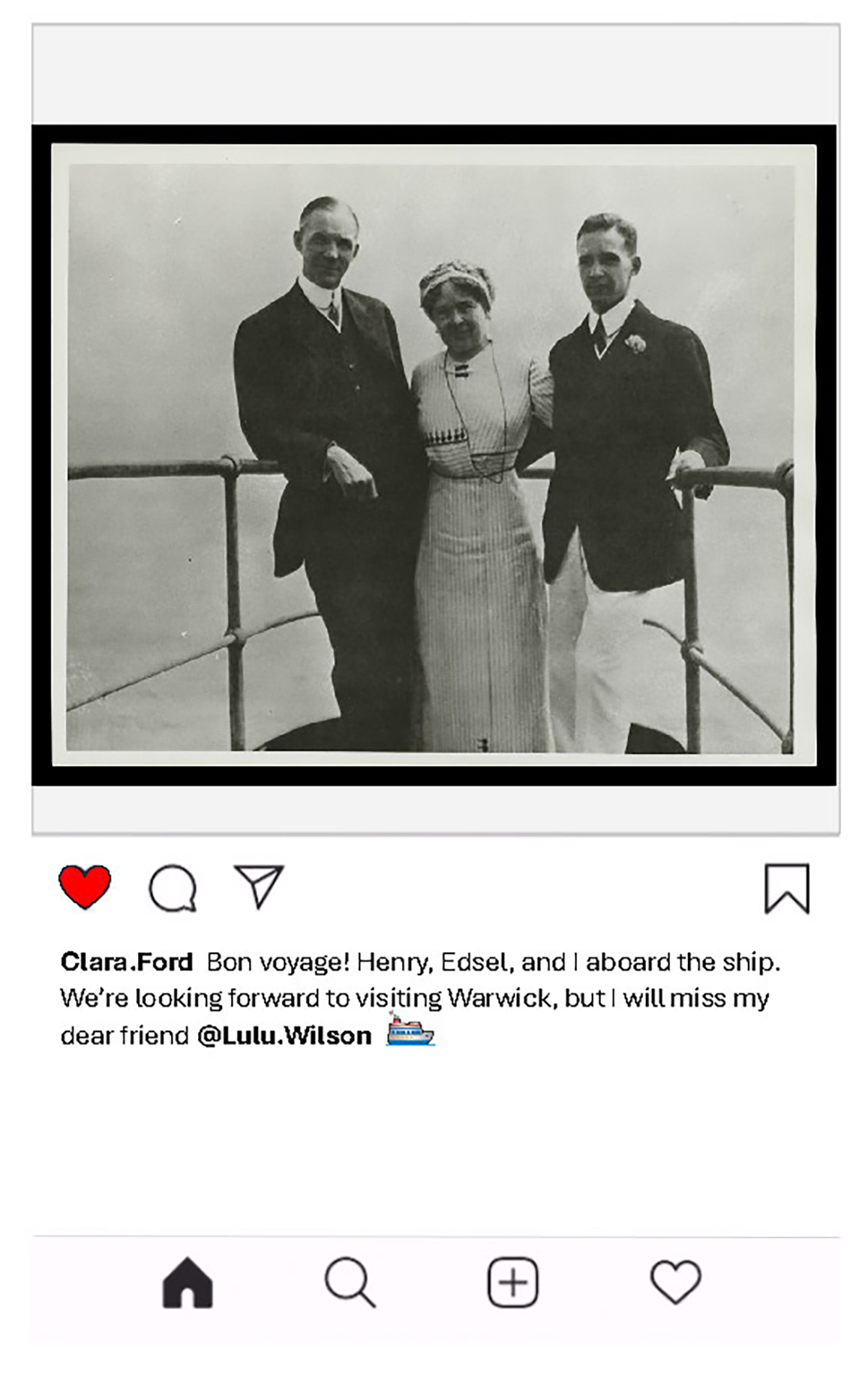

Clara Ford’s Travel Diaries

When traveling today, it is easy to document our journey through swift clicks of our phones and cameras. The people, sights, and sounds of a moment are captured and recorded through photos, videos, and social media posts making it easy to reflect on where we were and what we enjoyed.

The desire to document a memorable trip has remained a common tradition and in the age of Clara Ford, was accomplished through travel journals or diaries. Even with the advent of photography, film had to be thoughtfully allocated to document the most meaningful memories from a trip.

The Henry Ford's collections include several travel diaries written by Clara Ford dating from 1912 to 1945. Clara did not keep a diary for every trip she took. As the wife of Henry Ford, her travels were frequent and varied. Most of the diaries document her travels overseas, a momentous journey for anyone at that time, and winter retreats to Richmond Hill, Georgia, and Fort Meyers, Florida.

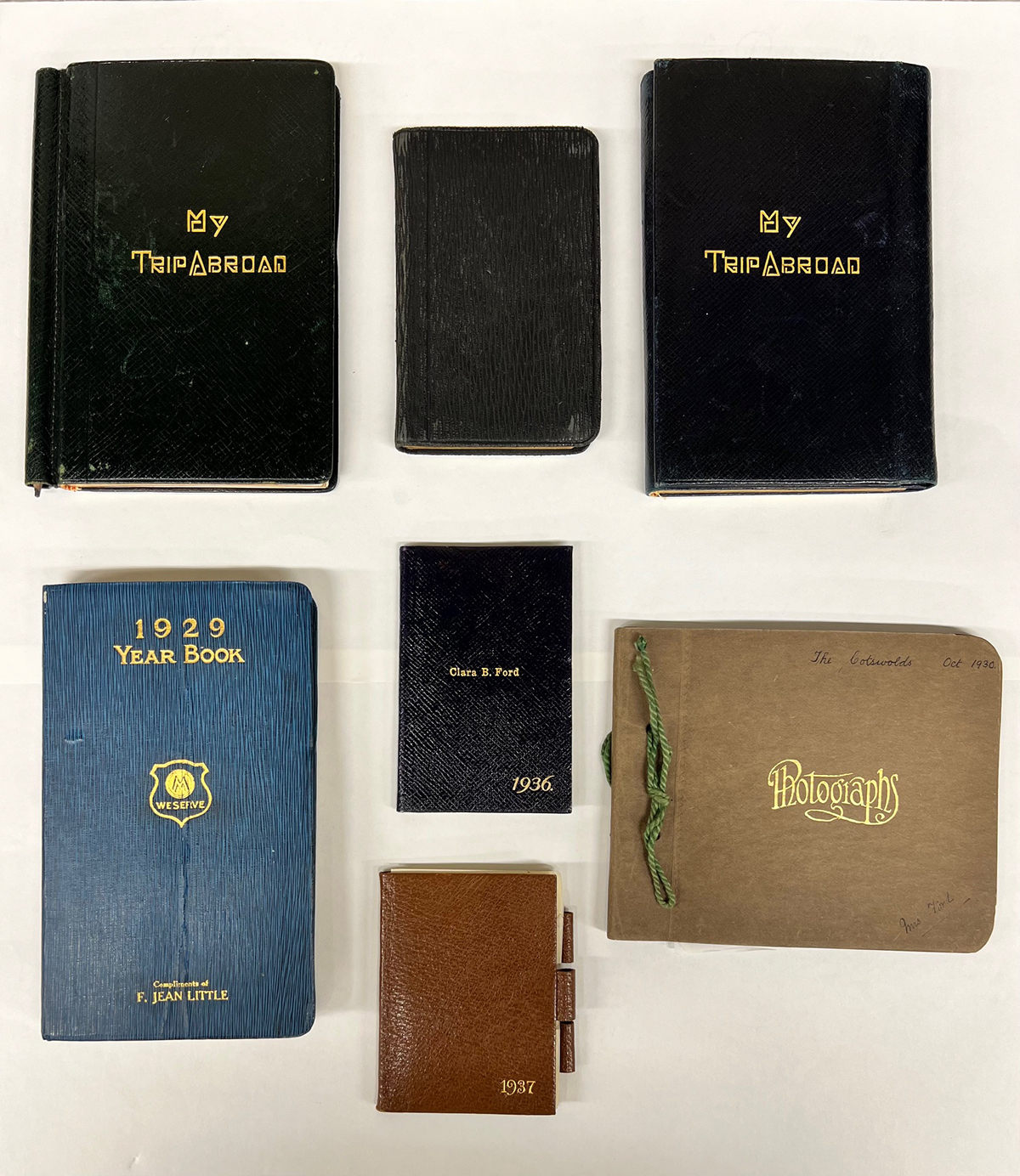

Clara Ford Travel Diaries. Accession 1, Box 105 and 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Unlike social media posts, travel diaries were not always intended for sharing or future publication. Entries were meant to document travel details and for personal reflection.

This means the writer was often sharing their thoughts more freely. For a notable figure like Clara Ford, travel diaries provide insight into her personal opinions and interests that might have been left out of an official record of her travels. They also provide a valuable record of Clara at a given time and place. They tell us who she interacted with, where she stayed, and what she saw.

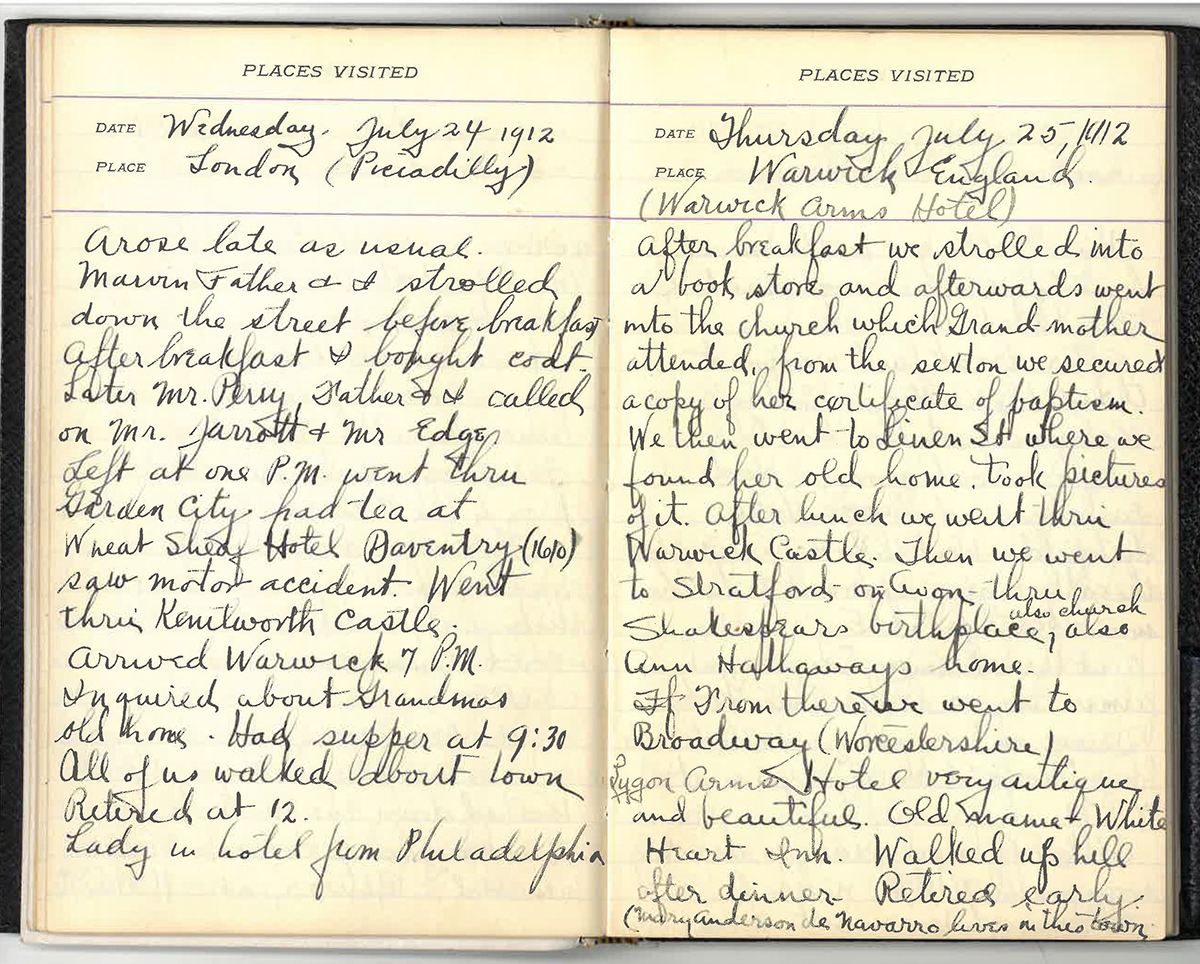

The earliest travel diary penned by Clara was for her first trip to Europe in 1912. She, Henry, and Edsel explored sites throughout Great Britain and France.

Henry, Clara, and Edsel Ford aboard Ship on their European Trip, 1912. / THF117563

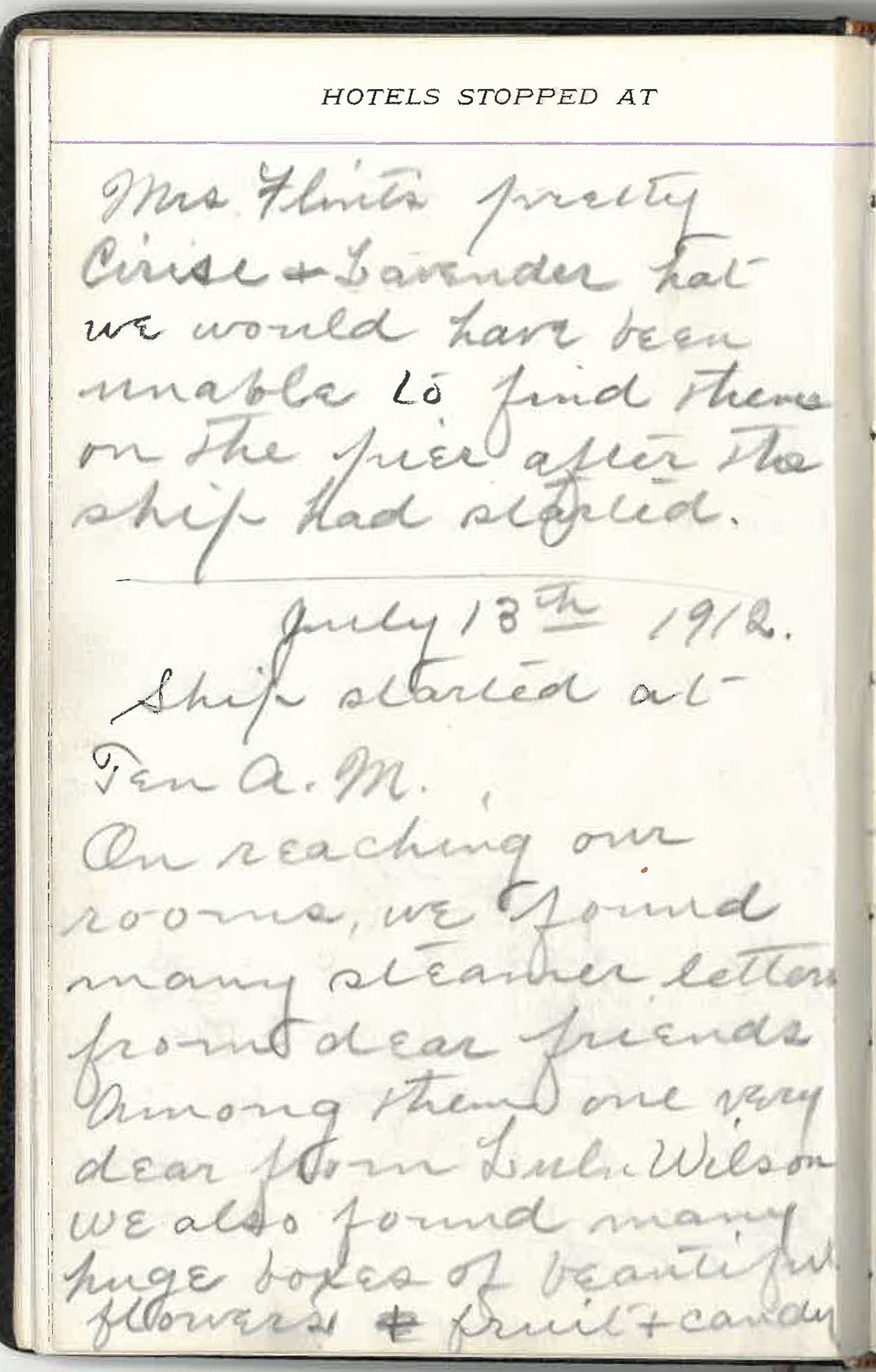

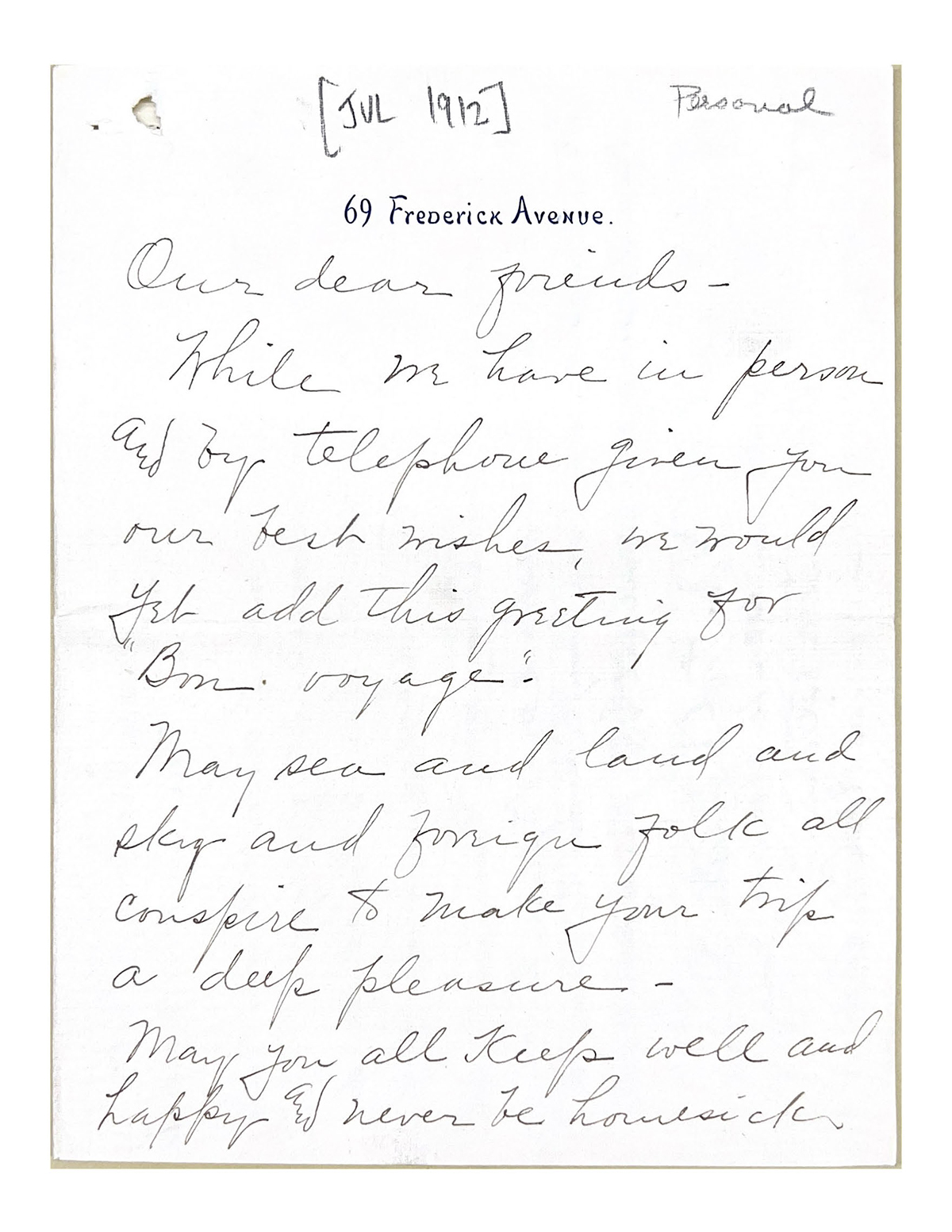

In one of the first entries, Clara documents the time the ship set sail and describes the warm welcome they received. Among flowers, fruits, and candy were several letters from friends wishing them a “Bon Voyage!” Clara references a letter from her close friend, Lulu Wilson, which we also hold in our collection. Connecting archival records like these illustrates a larger picture for historians and researchers.

Clara Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Letter to Clara Ford from her friend Lulu Wilson, July 1912. Accession 1, Box 66. / Image by Lauren Brady

In addition to Clara's diary, we also have Edsel's diary from this trip in our collection.

Clara Ford's and Edsel Ford's Travel Diaries, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

During their travels, they visited Clara's ancestral home. There are parallel accounts of the visit in both diaries. It reads as a meaningful visit for Clara who also describes important genealogical details about her family history that may not have been recorded elsewhere in our archival collections.

Edsel Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Clara Ford's Travel Diary, 1912. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

The Fords returned to Europe many times, including a trip in 1930 which Clara documented in a diary and a unique photo album. In her diary, Clara makes note of Henry's visit to Buckingham Palace before he departed for the Cotswold region of England where Cotswold Cottage had recently been acquired for Greenfield Village.

This visit received special commemoration in a photo diary with handwritten notes by Clara.

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

The album includes several snapshots of their visit culminating with a group photo at the former site of Cotswold Cottage. Clara's notes read like a short story as she describes the photos and recounts details.

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

"The Cotswolds" Photograph Album, 1930. Accession 1, Box 106. / Image by Lauren Brady

Clara's diary entries with descriptions of cities and historic sites she encountered are valuable to historians looking for written records of landscapes altered by wars and other major events. Her words help us understand Clara Ford as a historical figure, but they also help us understand a location as it stood at that moment in time.

We are grateful to have these valuable archival records, but it is fun to wonder how a modern Clara may have documented her travels. Perhaps a post like this...

If you have any questions or would like to learn more about our collections, please contact the Benson Ford Research Center at research.center@thehenryford.org.

Lauren Brady is a reference archivist at The Henry Ford.

Edsel Ford, Ford family, Henry Ford, Clara Ford, by Lauren Brady

Mopar Muscle at Motor Muster 2024

This 1970 Plymouth Road Runner Superbird, designed for NASCAR competition, exemplified this year's Mopar Muscle theme. / Image by Matt Anderson

Another summer is here, bringing with it another edition of our popular Motor Muster in Greenfield Village. Part car show, part street fair, and all fun, this year's event brought together more than 600 cars, trucks, motorcycles, bicycles, campers and boats all dating from 1933 to 1978. We like to spotlight a particular theme at each Motor Muster. This year marks the centennial of the first automobiles built and sold under the Chrysler Brand. Obviously, the 1924 model year is too early for our Motor Muster timespan, so we opted to celebrate Mopar Muscle — the Barracudas, Challengers, Chargers, Road Runners and more that made the Chrysler family of makes so popular during the muscle car era. Chrysler introduced the Mopar Brand in the 1930s for its original-equipment parts. ("Mopar" is a portmanteau of "motor" and "parts") But by the heyday of the muscle car in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Mopar was synonymous with high-performance cars from Chrysler's nameplates — especially Dodge and Plymouth.

Detroit Central Market was filled with representative Dodge and Plymouth muscle cars, in keeping with 2024's Mopar Muscle theme. / Image by Matt Anderson

Motor Muster routinely brings a stellar turnout of Chrysler-family muscle cars, and 2024 was no exception. This year we featured some of the best in Detroit Central Market. We always like to put interesting pieces from The Henry Ford's own collection in the Market, too. As extensive as that collection is, we don't have any muscle cars from the Chrysler brands. (We do have a 1965 example of the Pontiac GTO — widely considered the first true muscle car.) Instead, we featured three unusual Chrysler products. Our 1937 Chrysler Airflow represented the company's bold step into streamlining in the 1930s. Company founder Walter P. Chrysler had high hopes for the curvy car, shaped in part through wind tunnel tests. The Airflow's interior and mechanical components were equally significant, engineered to provide maximum comfort for passengers. Introduced for 1934 and sold under the Chrysler and DeSoto names, the Airflow attracted unprecedented attention from reporters and customers alike. But the car's many innovations caused production difficulties. Its unconventional looks — particularly its front end — also gave would-be buyers pause. Chrysler toned down the styling in subsequent model years, but Airflow sales still failed to meet expectations. DeSoto's version was cancelled in 1936, and Chrysler's ended after the 1937 model year.

This 1940 Chrysler Crown Imperial Parade Car carried VIPs through New York City for almost 20 years. / Image by Matt Anderson

Our 1940 Chrysler Crown Imperial Parade Car had a happier story. The stately car went to New York City where it served as the Big Apple's official parade car for nearly two decades. More than a hundred dignitaries — politicians, military leaders, diplomats, and notable personalities in the arts, sciences and athletics — rode in the car in ticker-tape parades through Manhattan's famed “Canyon of Heroes.” Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ralph Bunche, Winston Churchill and A. Philip Randolph were just some of the parade car's many distinguished passengers.

Our Chrysler Turbine engine from 1964 was no less important in terms of its technology. Turbine engines use the power of compressed, heated air to turn turbine blades that provide rotary motion to a car's wheels. Mechanically, turbine engines are far simpler than conventional piston engines, and this fourth-generation Chrysler turbine unit boasted 80 percent fewer moving parts. Turbines are also enormously flexible in terms of fuel. This engine could run on anything from unleaded gas to diesel fuel to kerosene to peanut oil. Many companies experimented with gas turbine engines after World War II, but only Chrysler put them into the public's hands. Chrysler built 50 turbine-powered cars and lent them to everyday Americans to get real-world feedback. Users loved the smooth ride and low maintenance but complained about sluggish acceleration and poor fuel economy. Most of the 50 cars were scrapped, but Chrysler gifted a complete car and the showcased engine to The Henry Ford in 1966. Chrysler ended its turbine development program in 1979.

It's not a car, but this late 1970s boat is indeed a Chrysler product. / Image by Matt Anderson

In recent years, Motor Muster has grown to include a small number of boats and outboard boat motors, displayed in their element alongside Suwanee Lagoon. Although it's an often-overlooked part of the company's history, Chrysler manufactured boats and boat engines for some 15 years, from the mid-1960s into the early 1980s. Chrysler Marine (the company’s watercraft division) built everything from small fishing boats to speedboats to sailboats. Some of its marine products shared parts — and even model names — with the company's automobiles. This year's Suwanee Lagoon exhibit included a Chrysler Marine boat built and used in the late 1970s for the company's own testing and development program, as well as a number of Chrysler outboard motors.

The two-seat yellow and white vehicle seen here was branded a PPV — a people-powered vehicle / Image by Matt Anderson

While the cars are the stars, Motor Muster always features several trucks, fire engines, motorhomes, travel trailers, motorcycles and bicycles, all from the mid-1930s to the late 1970s. Highlights from the pedaled class included a 1973 PPV, or People-Powered Vehicle. These two-seat conveyances were built by the EVI company of Sterling Heights, Michigan, and sold for about $380. They had room for two people (each of whom could help pedal) and space for luggage. Though the PPV had some appeal during those oil-crisis days of soaring gasoline prices, it wasn't practical enough to completely replace the family car.

This 18-foot Holiday House travel trailer offered an alternative for those not fond of Airstream's bulbous look. / Image by Matt Anderson

As is custom, auto camping historian Daniel Hershberger assembled and presented on a wonderful collection of mid-20th century travel trailers and cars near Scotch Settlement School. Highlights included a 1962 Holiday House trailer. Improbably, these trailers were the brainchild of David Holmes, president of the Harry & David mail-order fruit basket company. Fruit baskets were a highly seasonal business, peaking in the fall and through the December holidays. Holmes, looking to keep his employees and facilities busy during the rest of the year, hit on the idea of building travel trailers, which sold best in spring and summer. Holiday House offered trailers in 17-, 19- and 24-foot lengths, with gleaming aluminum skin over wooden frames. Unfortunately, the idea didn't work as well as Holmes had hoped, and Holiday House trailers were only produced for a few years. Recently, the brand name was revived on modern trailers built by another manufacturer.

In addition to Mr. Hershberger's presentations, two other experts offered talks throughout the weekend in Martha-Mary Chapel. Jim Johnson, Director of Greenfield Village and Curator of Historic Structures and Landscapes, spoke about the unique challenges of driving during World War II, when new cars weren't being manufactured and rubber and gas rationing curbed Americans' non-essential travel. We also had a special guest presenter. Richard J.S. Gutman shared stories and photos from his lifetime studying, visiting and preserving America's roadside diners. Mr. Gutman's timing couldn't have been better — he and his work are the subjects of the current Dick Gutman, DINERMAN exhibit in the Collections Gallery in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

Historians Roger Wojtkowicz, Jim Wagner and John Wagner provide commentary on a 1956 Chevrolet during pass-in-review. / Image by Matt Anderson

Beyond the special presentations, Motor Muster 2024 saw the return of our popular pass-in-review sessions, in which expert historians offer insights on participating vehicles as they drive past the Main Street reviewing stand. Automobiles were broken into separate sessions by decade, while commercial vehicles, motorcycles, bicycles and race cars each had their own dedicated pass-in-review programs. Naturally, we held special Mopar Muscle sessions on both Saturday and Sunday to celebrate this year's theme.

Competition cars like the 1941 Allard K1 at left and the 1962 Austin Mini Cooper at right – British vehicles both – sat near Town Hall. / Image by Matt Anderson

If all those motor vehicles and programs weren't enough, Motor Muster also featured a range of historic vignettes keyed to each of the show's five decades. Timeless Blues music was heard from the porch of the Mattox Family Home, the Village Cruisers vocal group performed a medley of 1950s hits at the Lodge, and the Together Band provided a concert of 1970s classic rock on the Main Street stage on Saturday evening. And yes, there was Historic Base Ball, too, as Greenfield Village's own Lah-De-Dahs played three games over the weekend.

The whole event was capped on Sunday afternoon with our awards ceremony. Visitors got to choose their favorite vehicles from the various decades through popular choice voting. We also gave two Curator's Choice prizes for unrestored vehicles. This year's unrestored winners included a 1951 Ford Deluxe and a 1973 Oldsmobile Cutlass S. The full list of winners is available here. The ceremony provided a perfect end to another great show.

Matt Anderson is curator of transportation at The Henry Ford.