Lifelong Companions

Animals — real, imagined and animatronic — play significant roles in the fabric of our lives, communities and cultures.

By Sassafras Lowrey

Throughout our lifetimes, animals, especially pets, often help form some of our closest connections. Across cultures and geography, the relationship we have with earth’s creatures big and small is a unique part of the human experience.

When asked why animals are so important to us, Alan Beck, professor emeritus of animal ecology in the Department of Comparative Pathobiology at Purdue University, noted that “pets have a place in almost all cultures. It’s not just an American thing or a European thing.” Beck, who centered his work and career on the role of animals in our lives, calls out our obsession with pets and our connection to animals as a universal human phenomenon.

What helps make this animal-to-human association so unique? It is nurtured early on in our development, whether there is direct contact with animals or not. From fairy tales about talking bears with chairs, porridge and beds to Sesame Street’s iconic Big Bird and today’s popular children’s shows like Peppa Pig or Bluey and her lovable Australian cattle dog family, animals are often central figures in the stories and oral histories children consume in large quantities from an early age. Dating back to the 18th century, in fact, the earliest stories published specifically with children in mind featured animals in key roles. Classics like Winnie-the-Pooh, The Velveteen Rabbit and Charlotte’s Web, or more contemporary Disney movies or modern-day animated TV shows like PAW Patrol, all aim to help children learn important life lessons via anthropomorphized animals as they grapple with friendship, love, grief, loyalty and belonging. Children see themselves, their families and their friends through these lovable characters as they grow and crave understanding of their own emotions.

Continue ReadingWhy Should Museums Diversify Their Library Collections?

Illustration by Neka King

I like to think of museum collections like most parts of society, in that they are always growing. The Henry Ford is a history museum that talks about innovation on a wide scale, which should mean all types of people can see themselves in our collections. For me, that translates to collecting books that tell stories for everyone, for both our research library and our rare book collection. Recently, I worked with one of our associate curators to add more pop-up books to the collection, which allows us to talk about both paper arts and childhood experiences. Other times, it might mean adding LGBTQ+ reference texts to the research library so our teams can tell communities’ stories in a sensitive and accurate manner.

It is important for us to see gaps in the collection as opportunities for growth and learning. Whether these gaps are related to different racial identities, age groups, abilities or orientations, filling them is what makes a museum an inclusive place. While such changes are not always easy, we know as a museum we’re only as strong as our collections — that what we choose to collect and care for has meaning for us as stewards but also for our guests, who expect us to tell their stories and want to see themselves represented in history.

Continue Reading

J.C. Leyendecker: America’s Master Illustrator

One of the most prolific and popular artists of the early 20th century, J.C. Leyendecker created iconic advertising and magazine illustrations that made a lasting impression on American culture.

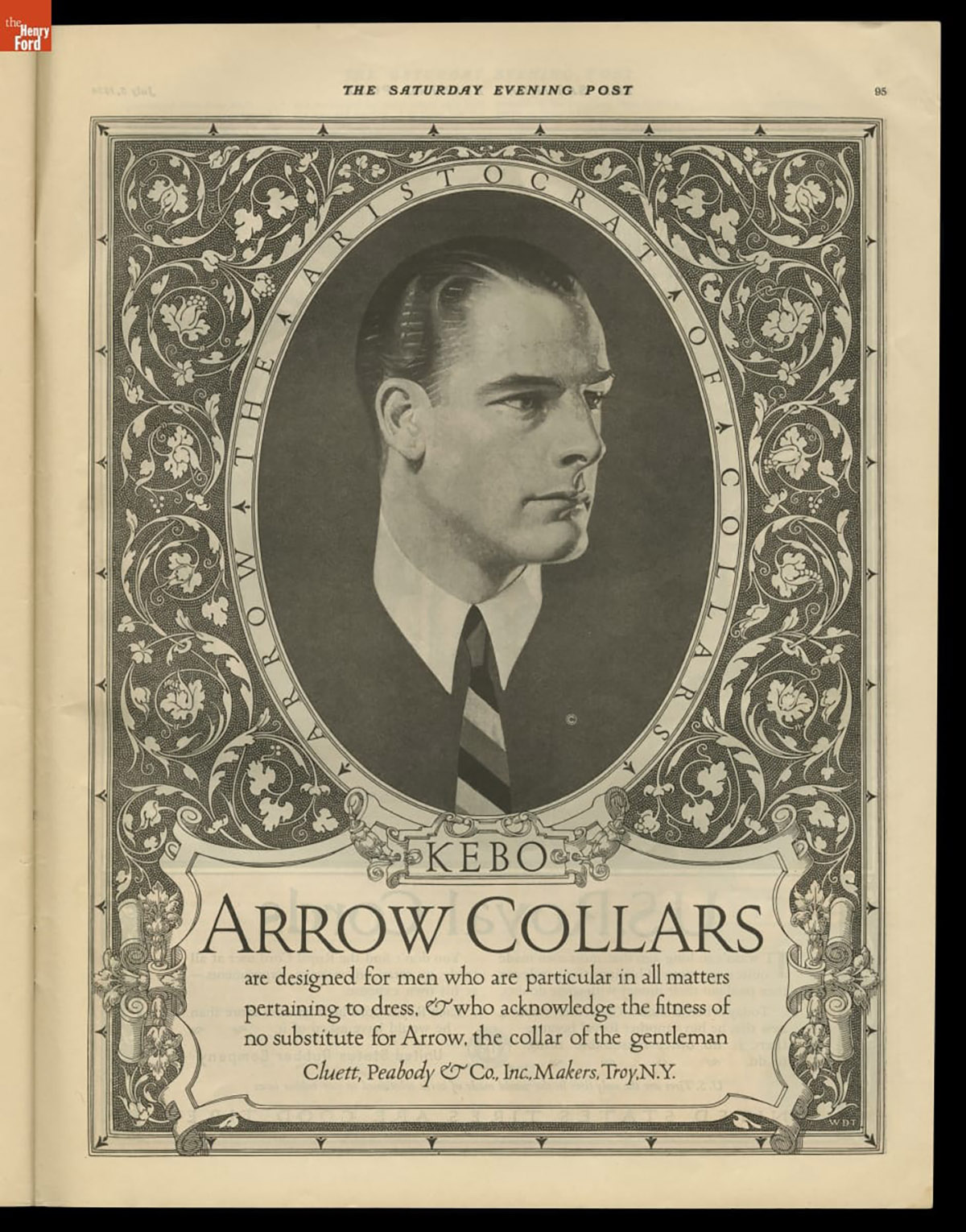

Advertisement for Arrow Collars, featuring Leyendecker’s iconic Arrow Collar Man, The Saturday Evening Post, July 5, 1924. / THF704785

Advertising

Joseph Christian Leyendecker, known as J.C., was born in 1874 in Germany. He moved with his family in 1882 to Chicago, where he studied art and entered the burgeoning field of commercial illustration. Leyendecker honed his artistic skills in Paris during the 1890s, when advertising posters by artists including Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Jules Chéret reached the height of their popularity.

Continue ReadingThe 1960s were a decade filled with turbulence and change. The country was beginning to come out of the fog of grief caused by the death of President John F. Kennedy, and the healing was still raw.

A reckoning had been in the works for decades regarding the nation's position on civil rights. From Jim Crow laws to Supreme Court decisions, change was coming, and not everyone was excited about it. The demand for equality was now.

“This is CORE, Congress of Racial Equality” pamphlet, circa 1959. / THF8258

The 1964 Civil Rights Act was pivotal in helping to create equality for all people. The act impact affected more than just the Black community in the United States; it also affected the Indigenous community, Asian community and gender equity and helped to lay the groundwork for the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Continue ReadingWhat We Wore: Aprons

The current What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, on display until April 17, 2024, features aprons that protect, connect, identify, embellish, and advocate.

Left: Mother and daughter aprons worn by Cindee Mines and her daughter Megan, 1978-1980. Gift of Cindee Mines. / THF370635, THF370633. Right: Christmas cookie cutter set, about 1970. / THF190022

Continue Reading

What do you think of when you think of a novel? Is it a single bound volume you picked up from your nearest bookstore or maybe a collection of words in a file you can read on your phone or e-reader? If you were to go and read Dickens today, I am sure your first thought would not be to head to the grocery store and browse the magazine display. However, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, magazines were a popular way for readers to consume works of fiction in bite-size chunks.

The Henry Ford has a sampling of volumes and loose issues from the 1850s to the mid-1900s. Most notable is our run of Harper’s New Monthly, later just Harper’s Monthly Magazine. Harper’s original mission, as stated in its inaugural issue, was to “place within the reach of the great mass of the American people the unbounded treasures of the Periodical Literature of the present day.” The editors at Harper's recognized that the best writers of the time were not being sold in bookshops but instead were writing for periodical publications.

Continue ReadingWith Earth’s revolution around the sun, the changing of the seasons often brings with it a greater awareness of the role that light plays in our lives — from the sun setting earlier to shadows thrown differently across surfaces. Our adaptations that assist with navigating life in the dimming sunlight mean we are reliant on lighting devices to illuminate our lives — a relationship that has extended into the deep, dark corners of human history.

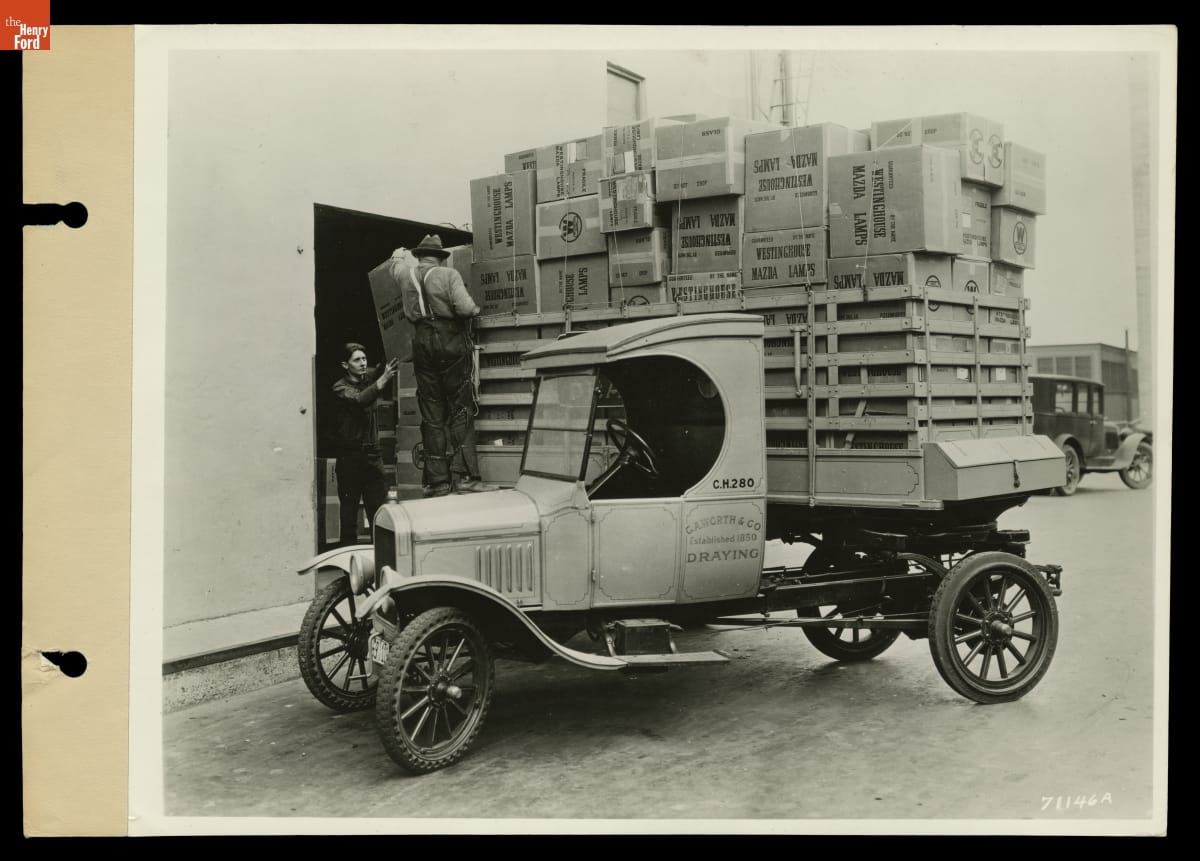

Loading boxes of Westinghouse Mazda Lamps onto a Ford truck, 1925. Many lighting companies, including Westinghouse, licensed the “Mazda” name from General Electric for their own tungsten filament bulbs. / THF122784

Beginning in the early 1920s, General Electric explored the human relationship with lighting devices when it commissioned illustrators Maxfield Parrish and Norman Rockwell to create a group of advertising illustrations for its popular light bulb known by its trademark as the Mazda lamp. Their artwork not only drew upon “the goodness of life in the light,” but also traced the history of lighting devices. The following is an exploration of those advertising posters, supplemented with a few examples from The Henry Ford’s collection of the lighting devices they celebrate.

Continue ReadingProtecting Pet Passengers with Sleepypod

Sleepypod carriers are designed to protect pets while traveling inside the family car. / THF185389

Improvements in automotive safety came gradually. Dodge Brothers crashed its early cars into brick walls to evaluate their strength during the mid-1910s. Ford offered laminated safety-glass windshields on its Model A cars in the late 1920s. And Chrysler and Plymouth models featured hydraulic brakes from their introductions in 1924 and 1928, respectively. But focus on seat belt use and scientific crash testing with anthropomorphic dummies didn’t come until the 1950s.

Continue ReadingFord Motor Company Advertising and 5 Influential Artists

Known as the “Golden Age of Illustration,” the decades surrounding the turn of the 20th century were a prosperous time to be an artist in the business of illustration. Technological advancements in papermaking and the increasing affordability of color printing, along with improvements in the railroad and postal systems, launched an unprecedented era for publishers. By the 1920s, this improved ability to reach audiences led to a national demand for illustrations in printed literature like books and magazines, spurred on by rising consumerism and tantalizing advertising revenue.

These new employment opportunities offered artists the possibility of becoming a household name — illustrations commissioned for national advertising campaigns or featured on the covers of widely distributed publications could be viewed by countless Americans. As with other major companies of the period, Ford Motor Company tapped into a growing pool of artistic talent for its advertising efforts. Below are the stories of five artists who not only elevated Ford’s brand awareness through their own art but also helped shape the visual culture of mid-20th-century America.

Continue ReadingIllustrating the Holidays: Christmas Cards by Tyrus Wong

Americans love to send — and receive — Christmas cards. Since the late 1800s, Christmas card production has grown, aided by inexpensive printing technologies and a prosperous — and increasingly mobile — American population. After the Second World War, greeting card companies looked for ways to outshine their competitors. Some companies commissioned production artists, animators, and illustrators who worked for West Coast film studios to create Christmas cards that appealed to mid-century Americans' tastes. Tyrus Wong, who worked for Disney and Warner Brothers Studios, is considered one of the finest Christmas card artists from the 1950s, '60s and '70s.

"Snow Bird," designed by Tyrus Wong for California Artists, 1955. / THF624835

Continue Reading