Relevancy Remains

Relevancy Remains

In Your Place in Time, guests explore past technology, examining how it connects generations both present and absent

By Kristen Gallerneaux, curator of communications & information technology and editor-in-chief of digital curation at The Henry Ford.

Since 1999, visitors to Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation have experienced the Your Place in Time exhibit — and have increasingly found it challenging to find their place within it. The original concept for this exhibit was to use artifacts and immersive vignettes in such a way that our guests could learn how everyday technologies shaped the social and cultural values of various generations that came of age in the 20th century. Your Place in Time addresses five such moments: the Progressive or “Greatest” Era, the War or “Silent” Generation, Baby Boomers, Gen Xers and the Next Generation — now more commonly referred to as millennials.

But how does this exhibit remain relevant, given the fact that we are now almost two-and-a-half decades into the 21st century? And how does it serve visiting Gen Y millennials and Gen Z “zoomers,” born on the cusp of the two centuries? Or even more so, the current generational cohort — born between the early 2010s and mid-2020s — that social researchers have dubbed Generation Alpha?

Continue ReadingKaysera Stops Pretty Places, a member of the Crow and Northern Cheyenne Tribes of Montana, should turn 23 this year. Like many other Indigenous women and girls nationwide, Kaysera went missing and was found murdered, with no one held accountable after almost five years.

Kaysera Stops Pretty Places grew up in Big Horn County, Montana, and on August 14, 2019, she celebrated her 18th birthday. Ten days later, Kaysera was reported missing. Her body was recovered on August 29. However, her family was not notified until September 11. There are still many questions concerning Kaysera’s disappearance and death.

In 2018, the Urban Indian Health Institute released an extensive study on the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) crisis. As of 2016, there were 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women. Still, only 116 were logged into the Department of Justice’s database, the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. The study examines various factors that led to the MMIW crisis, an issue within reservations and urban Indian populations.

Continue ReadingOn April 30, 1789, 235 years ago, in the nation’s first capital of New York, George Washington was sworn in as the first president of the newly formed United States of America. From that moment on, many aspects of Washington’s legacy would be built on myth, leaving out important parts of history that would help us understand the man and tell a fuller story. This isn’t to say that Washington didn’t do extraordinary things in his lifetime. Still, when we peel away the layers, we find that he was an ordinary man who lived in exceptional times and wasn’t as perfect as he is often portrayed.

Washington was born on February 22, 1732, on Popes Creek Plantation, (also known as Wakefield) in Westmoreland County, Virginia. In 1734, the Washington family moved to another property they owned, Little Hunting Creek Plantation, which was later renamed Mount Vernon. While Washington never received a formal education, he did have access to books and a private tutor. At the same time, he studied geometry and trigonometry on his own, for his first job as a surveyor.

Continue ReadingFrom Dayton to Dearborn

A rare collection of correspondence reflects the process of relocating the Wright brothers' buildings to Greenfield Village.

By Jennifer LaForce, Managing Editor, The Henry Ford Magazine

Both the Wright brothers’ cycle shop and family home in Greenfield Village are popular spots for the thousands of guests that visit The Henry Ford each year. During spring and summer, it’s not uncommon to see crowds surround the structures as they listen to presenters talk about Wilbur and Orville Wright, their bicycles and aircraft.

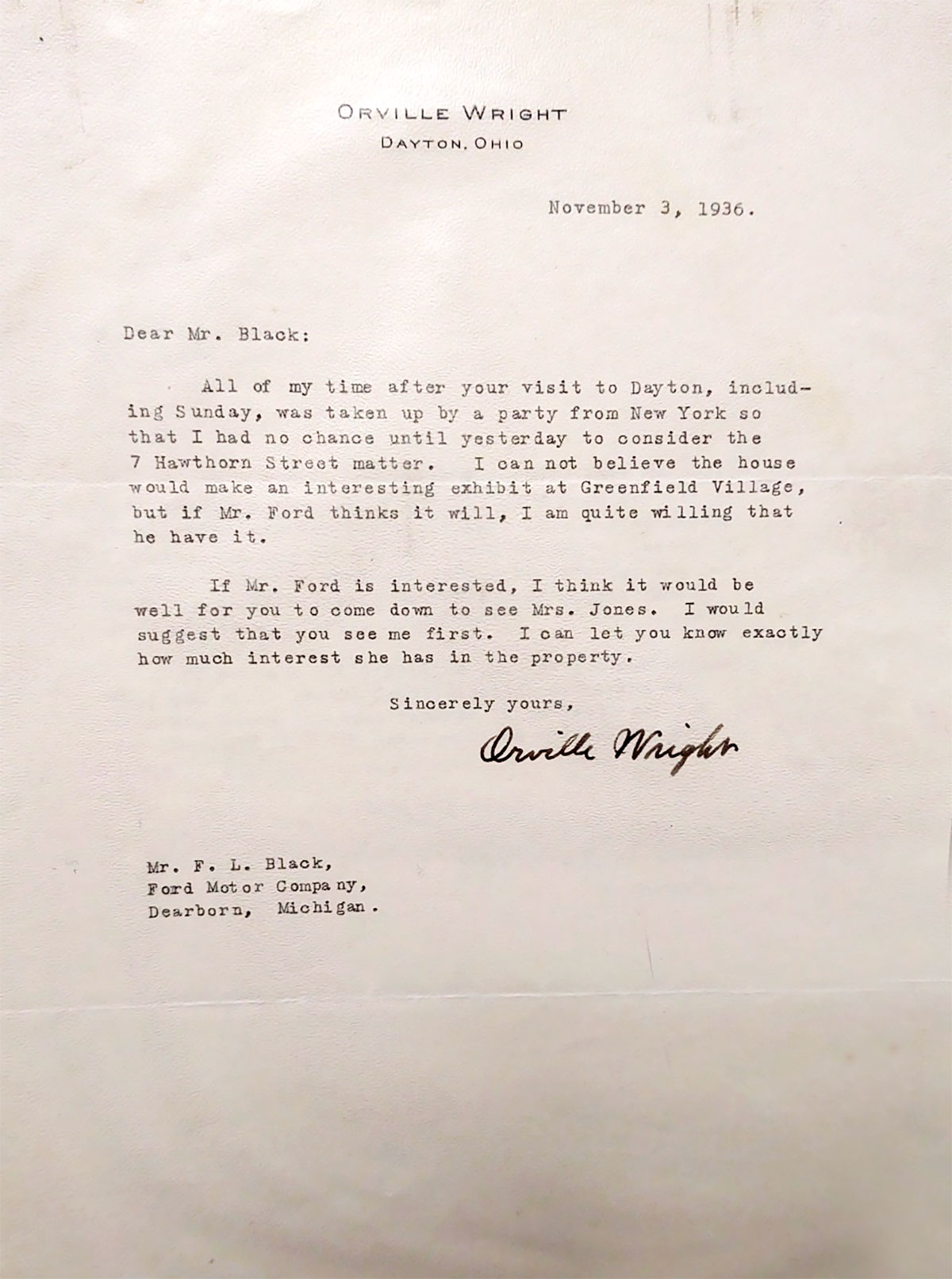

Letter from Orville Wright to Fred Black about Acquiring Wright Home for Greenfield Village, November 3, 1936 / THF714291

The Henry Ford recently acquired correspondence that helps bring to light how the buildings came to be in Greenfield Village in the late 1930s. It’s a collection of letters and other materials from former The Henry Ford staffers Fred Black and Fred Smith. Close liaisons to Henry Ford, Black and Smith are considered legendary in The Henry Ford’s early leadership, both acting in varying managing and

Pure-Pak®, Elopak and Sustainable Packaging

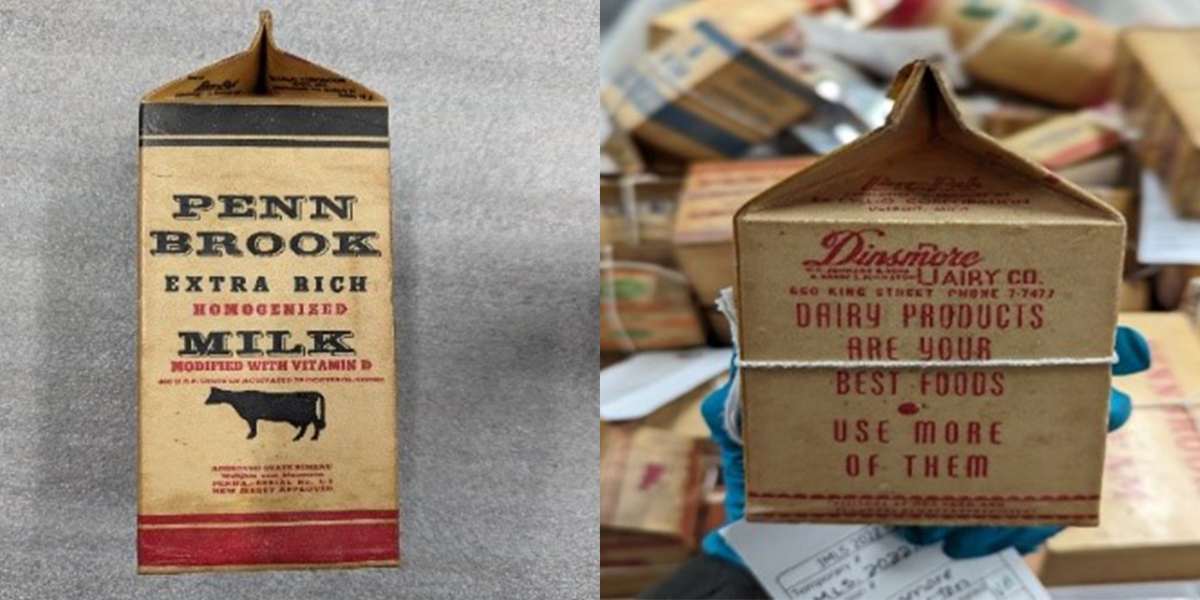

These Pure-Pak® paper cartons entered The Henry Ford’s collections in 1971 as part of a donation from David Gwinn, president of Pennbrook Milk Company. They document a type of disposable paper packaging for liquids that has a long history and current significance as manufacturers rethink their products in light of environmental stewardship.

Penn Brook carton and Dinsmore Dairy carton / reference photos

The earliest milk containers were metal, ceramic or glass. Urban consumers concerned about product purity and without a dairy cow purchased milk in mass-produced glass bottles starting after 1883. The inventor of these glass milk bottles, Hervey D. Thatcher, embossed them with “Absolutely Pure Milk” and “The Milk Protector” to reinforce the utility of the reusable glass containers. You can read more about the Thatcher Glass Manufacturing Company Collection at the Corning Museum of Glass here. Milk delivery services delivered full glass bottles and picked up empties so dairies could sanitize and reuse them.

Continue ReadingGathered on the Green

Greenfield Village’s “commons” is a careful creation by founder Henry Ford

By Jennifer LaForce

It’s true that one of Henry Ford’s earliest visions for his historic Greenfield Village was to create a “commons,” an open piece of land within a village or town designed for flexible use by everyone in the community. It’s often a green space — known as a “village green,” in fact — that townspeople use for gatherings and celebrations.

Enamored with the village greens he had seen in New England, Ford envisioned Greenfield Village’s commons to be flanked by structures meant for public gatherings, such as a place of worship and a town hall. And if an example of an existing building ready for transport to Dearborn, Michigan, couldn’t be found, he just had originals designed and built on site.

Photo by Roy Ritchie

Greenfield Village’s Martha-Mary Chapel and Town Hall are both examples of original-built structures on the Greenfield Village village green. The chapel, which is based on a Universalist church from Bedford, Massachusetts, has been holding wedding ceremonies since 1935. Patterned after New England-style public meeting halls of the early 1800s, the Town Hall is often the site of crowd-pleasing theatrical vignettes.

Continue ReadingInvesting in Helping Others

Ford’s disaster relief efforts grow, serving more communities in need

By Jennifer LaForce

Last year, Ford Motor Company and its philanthropic arm, the Ford Fund, announced a five-year commitment to Team Rubicon, a veteran-led humanitarian organization that provides no-cost services to vulnerable communities in the wake of crisis and natural disasters such as hurricanes, floods, earthquakes and wildfires. The new Team Rubicon Powered by Ford builds on a long-standing relationship between the two organizations. And it builds on nearly 25 years of disaster relief efforts by Ford.

Photo by Joel Morales from Team Rubicon

“At the heart of Ford is our commitment to help out our communities in times of need and make it possible for our employees to volunteer their time and talent to help others,” said Bill Ford, Ford’s executive chair, in a press announcement. “The reality is weather-related disasters in the U.S. are becoming more frequent and more severe. That is why we are significantly expanding our relationship with Team Rubicon.”

Continue ReadingSocial Reform, Design and Craft at the Turn of the 20th Century: The Saturday Evening Girls, The Paul Revere Pottery and Clara Ford

The story of the Saturday Evening Girls (S.E.G.) is a compelling story of female empowerment in the early 20th century. The women who founded and the girls who became members of the S.E.G. — many of them immigrants of Jewish and Italian heritage — strengthened one another’s lives through social activities, education and artistry that built self-esteem, leadership qualities and wage-earning skills.

Daffodil centerpiece bowl, designed by Edith Brown, decorated by Sara Galner, dated March 1914 / THF193475

The roots of the story are found in turn-of-the-20th-century Boston, specifically an area where many immigrants settled called the North End. By the late 19th century, the area was a slum, consisting primarily of multistory tenement housing and light-manufacturing shops. Living conditions were generally rough, with families lacking private baths and central heating in their apartments. It was literally a hand-to-mouth existence in the first decade of the 20th century. Children of immigrants attended school if their parents could afford it, with many leaving before they got to high school, having to work to contribute to their family's income.

Continue ReadingMaple Trees and Family: A Long-Term Relationship

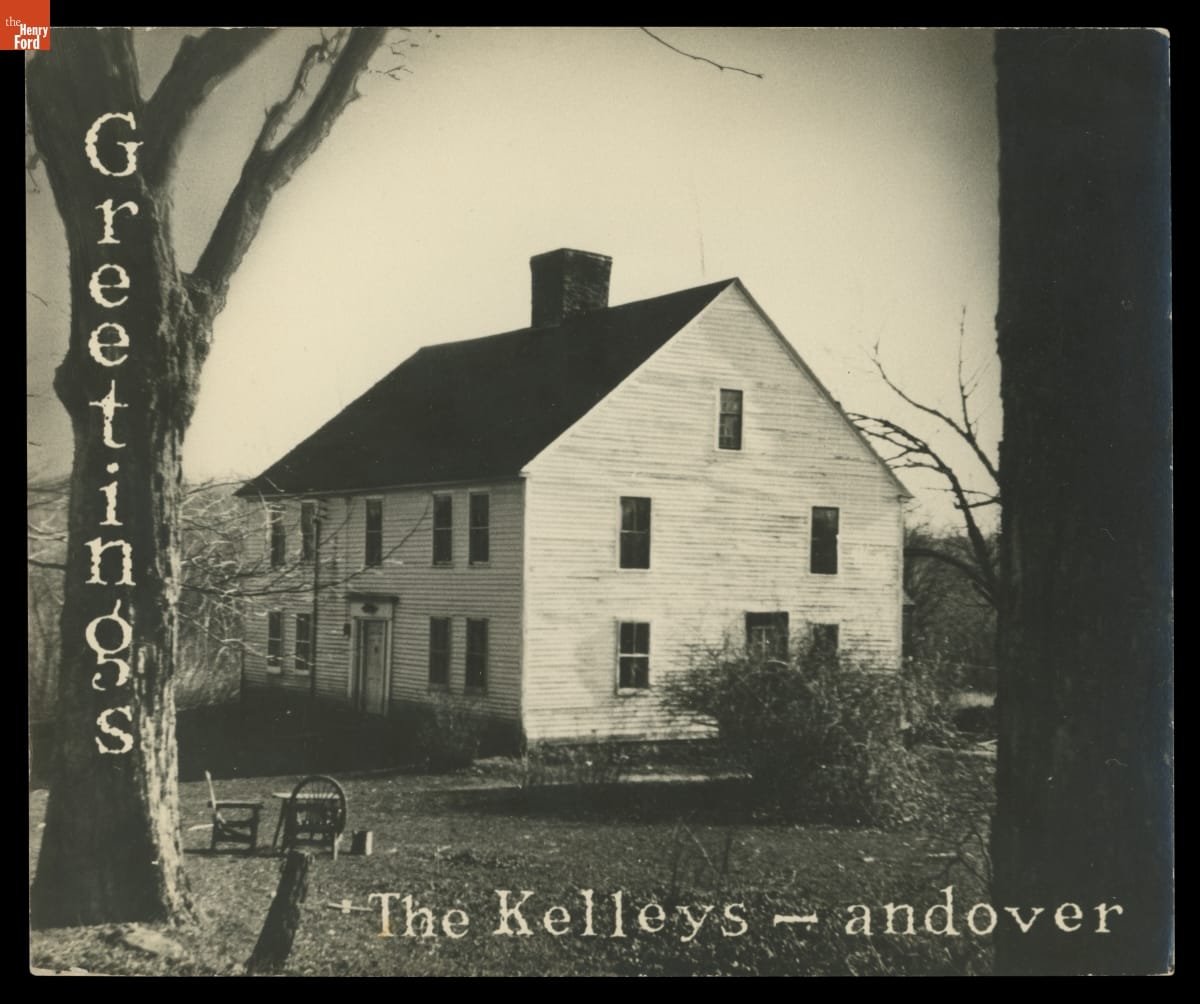

Maple sugaring on the New England family farm continued a long-term relationship between people and place. Maple trees bordering country lanes and front yards bear witness to an alliance at least 250 years old. The trees outlived the people, generation after generation. The Kelley family joined in the ritual during the 1950s as they started tapping trees. The following confirms the influence those trees (and their sap) had on the well-being of one family and their farm and on a wider rural community.

The Kelley family featured their new home, the house that Enoch Badger built more than 200 years before, on their 1953 Christmas greeting card. / THF706177

When Enoch Badger built his house in 1747, he planted a row of sugar maple trees at the same time. Mostly for making maple syrup, the trees had many side benefits. Hard maple wood was choice for utilitarian kitchenware, as firewood for cooking and smoking meat, and for heat. Roadside hitching posts stood under the trees, where horses tied to them could benefit from the shade.

Continue ReadingLillian Schwartz: Artist and Inspiration

As we enter the final month of the Lillian Schwartz: Whirlwind of Creativity exhibit at The Henry Ford — which also happens to be Women’s History Month — it seems a good time to acknowledge Lillian’s life and work as an artist who made groundbreaking contributions in the fields of creative computing and technology.

While Lillian’s skills as a painter and sculptor became evident decades before she began producing work at Bell Laboratories in the late 1960s, it was in this environment where she produced her best-known computer-mediated films and digital art. Her exposure and access to powerful bleeding edge technology at the Labs led to the creation of instantly iconic experimental films such as Pixillation, UFOs, and Enigma — among many other titles. These films continue to be sought after for exhibitions and film screenings globally, even today.

Views of the audience at the recent “Lillian Schwartz: Early Permutations” screening co-presented by the Aurora Picture Show and Moody Center for the Arts in Houston, TX. Images courtesy of Peter Lucas.

Continue Reading