Exploring the Depths of Our Collections

Preserving the past is resource-intensive, and The Henry Ford actively seeks grant funding to support its mission "to provide unique educational experiences based on authentic objects, stories, and lives from America's traditions of ingenuity, resourcefulness, and innovation." Some of these grants focus on enhancing collections storage, stewardship, and accessibility — both physical and virtual. In late summer 2024, the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) awarded The Henry Ford a two-year grant to clean, rehouse, and create digital records for artifacts related to power and energy, mobility and transportation, and communications and information technology.

Building on the progress made by previous grants, this project will focus on approximately 325 artifacts housed in The Henry Ford's Central Storage Building that require attention in these key areas. The Henry Ford is currently investing in upgrades to the HVAC system in the building, which will improve the ability to regulate the storage environment. In conjunction with those improvements, the grant work will address overcrowding and previous environmental issues, which in some cases have led to dirt, mold, and other forms of artifact deterioration. Each artifact will be moved, cleaned, and assessed for conservation needs. Registrar staff will update or create catalog records, working closely with curatorial staff to research additional context.

IMLS grant team members meet to discuss work progress. / Photo by Aimee Burpee

Of the 325 artifacts, about 100 priority artifacts identified by the curators will undergo conservation treatment to digitization standards, will be photographed at high resolution and made available online through The Henry Ford's Digital Collections. Curators and associate curators will create digital content, such as blog posts, to highlight these artifacts. Additionally, curatorial staff will write descriptive narratives for the website, providing essential historical context for public audiences.

The IMLS Collections Specialist takes a reference image of each artifact for the catalog record, such as this 1915 Gentry and Lewis V-8 Automobile Engine for the Model T (left), then, after conservation intervention, Photography Studio staff photographs this priority artifact for publication on digital collections. / Photo by Colleen Sikorski (left), THF802658 (right)

Work on the grant began in the fall of 2024, and the first priority artifact to be conserved is a six-cylinder General Motors 6-71 diesel engine — a legend in its own right. Introduced by General Motors' diesel engine division in 1938, the two-stroke unit powered everything from farm tractors and stationary generators to trucks and buses (including the 1948 GM bus on which Rosa Parks made her historic stand). GM produced variants with two, three, four, six, eight, twelve, sixteen, and twenty-four cylinders, practically guaranteeing there was a Detroit Diesel in whatever size and with whatever horsepower a customer required.

For 40 years, this GM 6-71 engine provided faithful service aboard Jacques Cousteau's ship Calypso / THF802646

The Henry Ford's Detroit Diesel just so happened to be used on one of the most celebrated scientific vessels of the 20th century: Calypso, the former World War II minesweeper converted into a floating laboratory by French oceanographer Jacques Cousteau. From 1950 through 1997, Calypso traveled the world's oceans for Cousteau's research, and for shooting many of his documentary television series and films. Calypso even visited the Great Lakes in 1980, when it traveled from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River to Duluth, Minnesota, some 2,300 miles away.

It's important to note that The Henry Ford's engine was not Calypso's source of propulsion. The ship's propellers were driven by two eight-cylinder General Motors diesel engines. Our six-cylinder engine was one of two units that ran the generators that produced electricity. Our engine didn't make the boat go, but it kept the lights on — arguably just as important a task. Of course, it wasn't just lights. Calypso's electric generators powered pumps, hydraulic systems, steering mechanisms, radar and navigation devices, and video equipment, among other necessities.

By the time our engine was decommissioned in 1981, it had been used on Calypso for 40 years, with an estimated 100,000 service hours under its belt. Calypso received two brand-new Detroit Diesel engines as part of a wider refurbishment in anticipation of a voyage to the Amazon River. General Motors gifted the decommissioned engine to The Henry Ford in 1986.

Vintage illustrations, like this one from a 1939 GM manual, guided efforts to conserve the Calypso engine. / THF721888

Through the IMLS grant project, conservators were able to clean the engine of accumulated dirt and dust, treat worn paint, and stabilize damaged gauges and controls. We were also able to replace a long-missing panel surrounding the starter button. Using period General Motors catalogs and manuals in the Benson Ford Research Center, we were able to design and 3D-print a new surround. Once the panel was painted to match, it became visually indistinguishable from the engine's original metal components. (Conservator notes, and inscriptions on the pieces themselves, identify replacement parts so as not to cause confusion in the future.) With that work done, the engine was photographed and given a new and much improved set of digital images on the website.

The Calypso Detroit Diesel is only the first of many important artifacts that will benefit from the IMLS grant and our ongoing work in the Central Storage Building. Stay tuned for future stories. It's a project that promises to be its own voyage of discovery.

This blog was produced by Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation, and Aimee Burpee, Associate Curator at The Henry Ford.

The American Promise: The Speech that Changed a Movement

Selma is a sleepy little town in Alabama that has an extraordinary history. Located on the shores of the Alabama River in the heart of Dallas County, Selma is also home to the Jackson family.

Dr. Sullivan Jackson met Miss Richie Jean Sherrod at a family picnic the summer of her junior year in 1953. The meeting was brief, but Dr. Jackson was smitten, and he called Miss Sherrod the next day and asked her for a date. The two started dating steadily after that.

Dr. Sullivan and Richie Jean Jackson on their wedding day, March 15, 1958. / THF708474

While Richie Jean attended college in Montgomery, Sullivan would often drive over to see her, and they would go out to eat and spend time together. After Richie Jean graduated from college in 1954, the situation changed as both tried to navigate their worlds and have successful careers, and the two decided to end their relationship. But the universe had different plans. After a time, they were soon back together, and on March 15, 1958, they were married and began to create a life together that would shape their roles in civil rights and voting rights activism in ways they never imagined.

Dr. Sullivan and Richie Jean Jackson on their wedding day with family. / THF708475

It was March 1965, and many thought the fight for civil rights was over. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had been signed the year before, and many wrongs had been righted. However, the fight for equality and the right to vote was far from over. Things would reach a point where the president at the time, Lyndon Baines Johnson, would address Congress and demand something be done.

The movement for voting rights spread throughout the South in the United States, but its center was Selma, Alabama. In February 1965, a group of activists and protestors gathered outside Zion United Methodist Church in Marion, Alabama, about 26 miles northwest of Selma. One such protester was Jimmie Lee Jackson. Though they share a last name, he is not related to that Jackson family of Selma. He was at the protest with his mother, Viola Jackson, and his grandfather, Cager Lee. While trying to protect his mother from the escalation in violence, Jimmie Lee was shot twice in the stomach by Alabama State Trooper James Fowler. Eight days later, he died from his wounds.

The death of Jimmie Lee Jackson became one of the factors in the march from Selma to Montgomery for voting rights. The first attempt at this march resulted in Bloody Sunday on March 7, 1965. That event and the subsequent Turnaround Tuesday March on March 9, 1965, led to President Johnson giving one of the most powerful speeches in support of his presidency.

Life Magazine, dated March 26, 1965, discusses the Voting Rights Movement and President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s March 15, 1965, speech throwing his support behind the Voting Rights Act. / THF715927

It was March 15, 1965, when members of the Jackson family and guests gathered in their homes to listen to President Johnson give this speech. This was also the seventh wedding anniversary for “Sully” and Richie Jean. The President began:

“At times history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man's unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama.”

His words bring back memories of the American Revolution and the Civil War, two events in which the country fought for freedom. As the president continues with The American Promise speech, he brings up the death of Jimmie Lee Jackson while discussing the violence inflicted upon those who merely wish to register to vote.

Life Magazine, dated March 26, 1965. / THF715929

The speech was written by writer and presidential advisor Richard Goodwin, who also worked for President John F. Kennedy. The President had decided on Sunday, March 14, that he would address the country the next night, March 15. Goodwin was assigned to write the speech at the last moment and had only eight hours to write. As a Jewish American, Goodwin pulled from his own experiences with anti-Semitic prejudice and discrimination.

The American Promise, more commonly known as the “We Shall Overcome” speech, hits on historic and contemporary moments leading to the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Invoking Patrick Henry’s famous “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” to the Declaration of Independence's statement that “All men are created equal,” the speech is the argument. It makes the case for a Voting Rights Act.

The President spoke about the barriers that had been put in place on Black Americans, from poll taxes to literacy tests, while also invoking the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, which guaranteed Black men the right to vote. This right was not always upheld.

The speech was 48 minutes and 53 seconds long. Seventy million Americans watched it, including the Jackson family and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The White House received 1,436 telegrams of support and 82 telegrams against the idea of a Voting Rights Act, and LBJ was interrupted over 40 times for applause.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr watched President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s speech from the living room of the Jackson Home on March 15, 1965. Photo feature in Life Magazine, March 26, 1965. / THF715931

In his speech, the President discussed the need for the Voting Rights Act, his intention to push Congress to pass it, and how passing that act fulfills an American promise to all citizens to be able to vote for their leaders.

Pulling from a song that had become the anthem of the Civil Rights Movement, President Johnson signaled that he heard the activists working on the ground in Selma and would answer the call. And the speech that reiterated the American promise forever would be known by a different name: We Shall Overcome.

“Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.”

The full text of the speech can be found courtesy of The American Presidency Project.

A video excerpt of the speech can be found at the LBJ Presidential Library.

Heather Bruegl (Oneida/Stockbridge-Munsee) is the Curator of Political and Civic Engagement at The Henry Ford. This blog is part of a series exploring the history of the Jackson Home, opening in Greenfield Village, 2026.

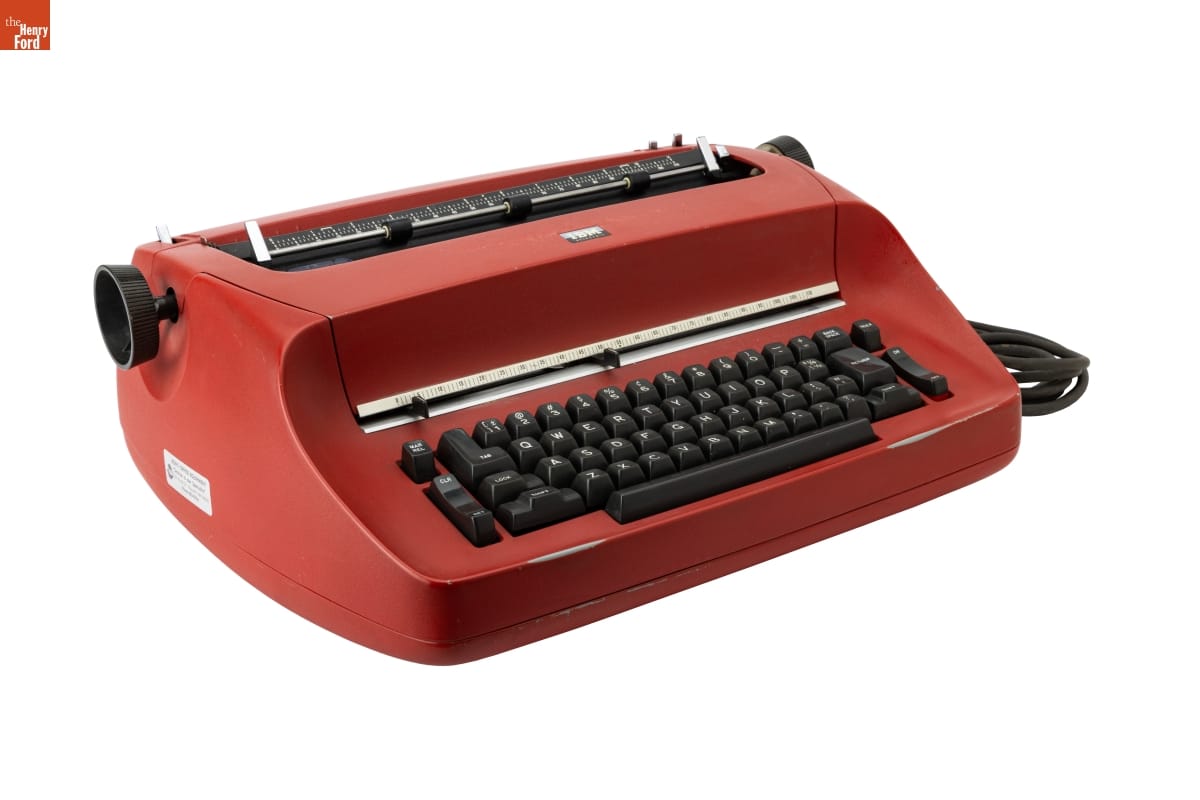

IBM Selectric Typewriter designed by Eliot Noyes in 1961. / THF802461

In August 2024, a monumental design collection arrived at the doors of The Henry Ford after an international journey nearing 600 miles. The collection was donated by the Stewart Program for Modern Design in Montreal, Canada, and represents decades of collecting by founder and philanthropist Liliane Stewart alongside her incredible staff, especially curator David Hanks and registrar Angéline Dazé. While Liliane Stewart and her husband, David, had a longstanding formal relationship with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (a pavilion named for the Stewarts houses a significant design collection donated by them in 1999), this portion of the considerable collection was offered to The Henry Ford upon the closing of the Stewart Program for Modern Design in 2024.

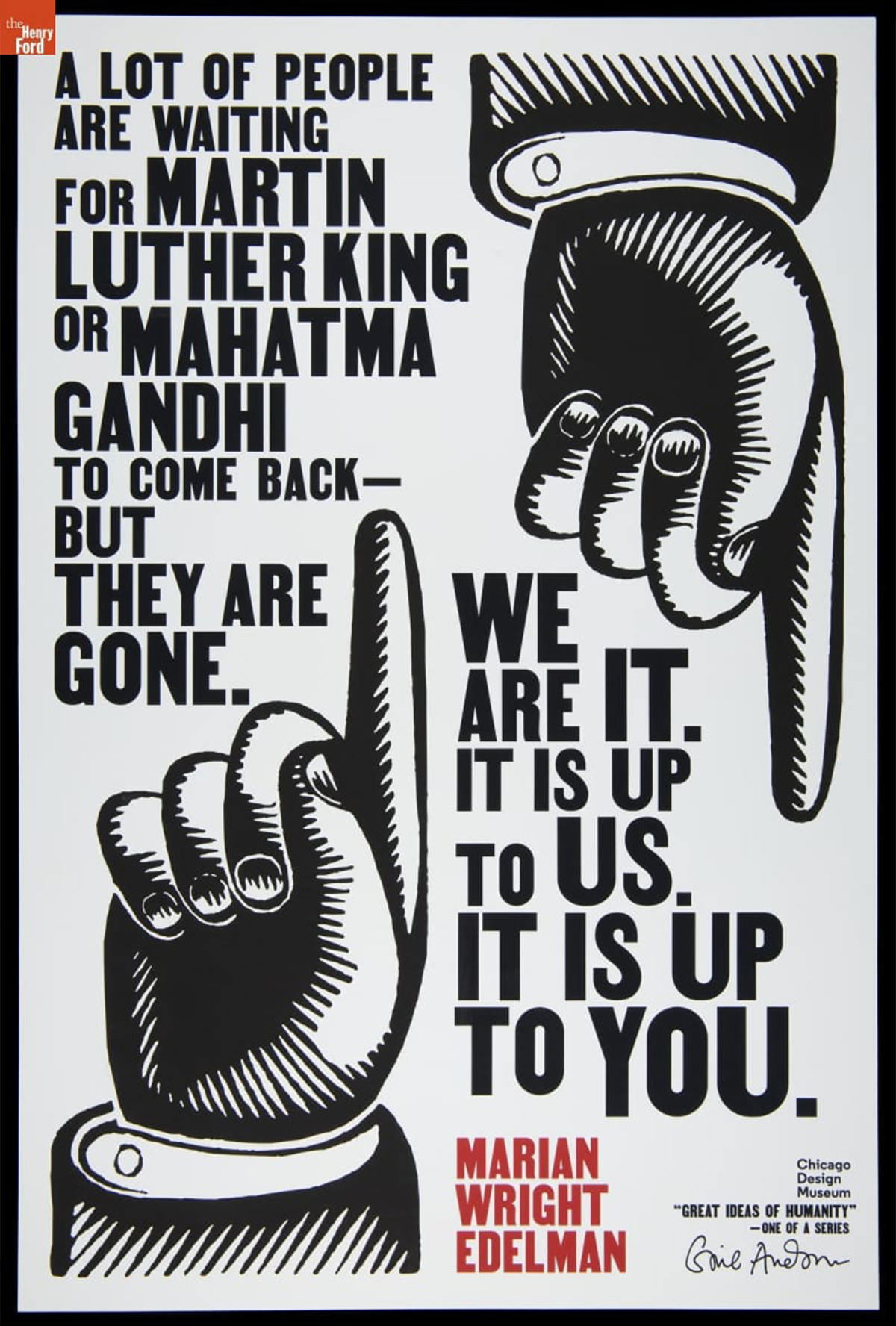

This poster, entitled “A Lot of People are Waiting for Martin Luther King... We Are It. It is Up to Us. It is Up to You. Marian Wright Edelman” was created by graphic designer Gail Anderson in 2018. / THF721539

The Stewart Program Collection at The Henry Ford includes over 500 objects, a library of more than 100 books and 500 periodicals, and an archive nearing 40 linear square feet. As design touches nearly every area of the museum, so too does this collection. The range in object type is vast — from ceiling lamps to bicycle helmets, teapots to stools, studio glass to adding machines and more, and spans over 140 years of design history, from the 1880s through 2020. The designers and companies represented in this donation are also remarkably wide-ranging and include some of the most celebrated names in design, as well as successful works by unknown designers. They were created by designers of various nationalities and manufactured in a range of countries —but every object had significant impact on American society and American design, through its retail availability on the American market or through its prominence and influence on American designers, reflecting the trajectory of globalization in design.

“Alaska” Vase by Italian designer Ettore Sottsass, 1982 / THF802469

The Henry Ford and the Stewart Program for Modern Design have compatible philosophies in collecting design. Both institutions hold a deep respect for design’s role in the everyday lives of people, in the problem-solving nature of good design, and the practice of prioritizing design in its cultural context. The Stewart Program Collection fits serendipitously within the museum’s existing holdings, while also stretching, expanding, and deepening the collection as well as pushing into new areas.

This Model 4706 Electric Clock, 1933-1934 by Gilbert Rohde was exhibited at the 1933-1934 Century of Progress International Exposition with the 3317 series furniture collection, also designed by Rohde. The Henry Ford holds numerous pieces from the 3317 series, including this dresser which is on display in the Fully Furnished exhibit. / THF802510

Collections Connection

In numerous instances, the objects donated by the Stewart Program happily supplement the strengths of our collections. For instance, The Henry Ford has an especially strong collection of furniture by pioneering designer Gilbert Rohde for the Herman Miller Furniture Company, including much of the bedroom set Rohde designed for the “Design for Living House” at the 1933-1934 Century of Progress International Exposition. However, we lacked the table clock exhibited in the bedroom. But as luck would have it, that particular clock was included in the Stewart Collection donation. Reuniting these objects that were designed to coexist will allow us to tell a fuller story about this moment in design history.

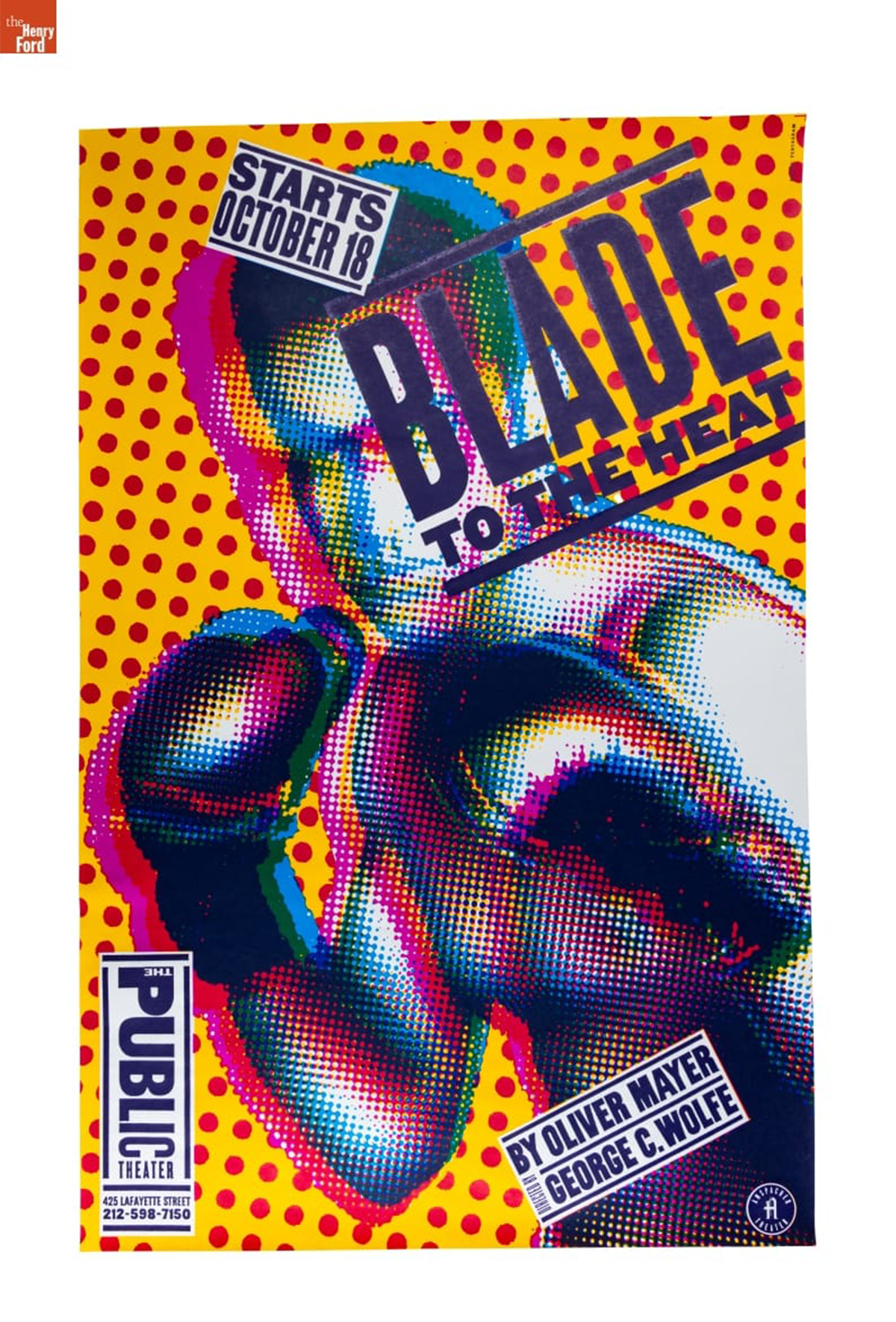

Numerous posters designed by Paula Scher were donated by the Stewart Program for Modern Design, including this “Blade to the Heat” poster designed for the New York Public Theatre in 1994. / THF802482

Designed by Women

In 2018, the staff of the Stewart Program for Modern Design embarked upon their Designed by Women project, which encompassed an ambitious new acquisitions program of objects designed by women, an expansive website, and digital exhibitions. Highlighting women designers across the globe from 1910 to 2024, the project has become a resource for the design profession as it showcases both well-known and lesser-known designers. Similarly, The Henry Ford has been working in recent years to expand representation of women in the design collections, with recent acquisitions like Lucia DeRespinis’ Beehive Lamp, Evelyn Ackerman’s Campesina Tapestry, and Gloria Caranica’s Rocking Horse. Many of the objects acquired by the Stewart Program for Modern Design for this project were donated to The Henry Ford, expanding our collection of objects designed by women, including a large collection of posters by pioneering graphic designed Paula Scher, a teapot by Edith Heath of Sausalito, California-based Heath Ceramics, a pendant necklace by Indigenous jewelry artist Angie Reano Owen, and many more.

Paula Scher’s “Bring in ‘Da Noise, Bring in ‘Da Funk” Poster, 1995 (left), Edith Heath Teapot, c. 1944 (center), Shell Necklace by Angie Reano Owen, 2014 (right). / Images courtesy of the Stewart Program for Modern Design

Check out the Selections from the Stewart Collection expert set for more information about some of the objects donated by the Stewart Program for Modern Design.

Eva Zeisel’s “Town & Country” Teapot, Teacups, and Saucers, c. 1945 / THF802477

Katherine White is Curator of Design at The Henry Ford. This blog post was adapted and expanded from the January-June 2025 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Personal Reflection by Lyn St. James

Lyn St. James / THF58579

As we celebrate Women’s History Month, I recently also celebrated my 50th year in motorsports, which has enabled me to reflect on not only my career, but the careers of other women in motorsports, and to take stock of what progress has, or maybe has not, been made in these last five-plus decades. While women have been racing since the early 1900s, it wasn’t until the 1960s that women started to make some noise and show up at the track letting folks know they were to be reckoned with. The one who made the most noise and rattled the grid in drag racing was Shirley Muldowney, who was the first female racer to earn a National Hot Rod Association (NHRA) Top Fuel drag racing license and went on to win three championships, becoming the first person to win two and then three Top Fuel titles. Yes, there were other successful women racers before Shirley, but no one had the ongoing success for many decades.

Drag Racer Shirley Muldowney, 1983 / THF624819

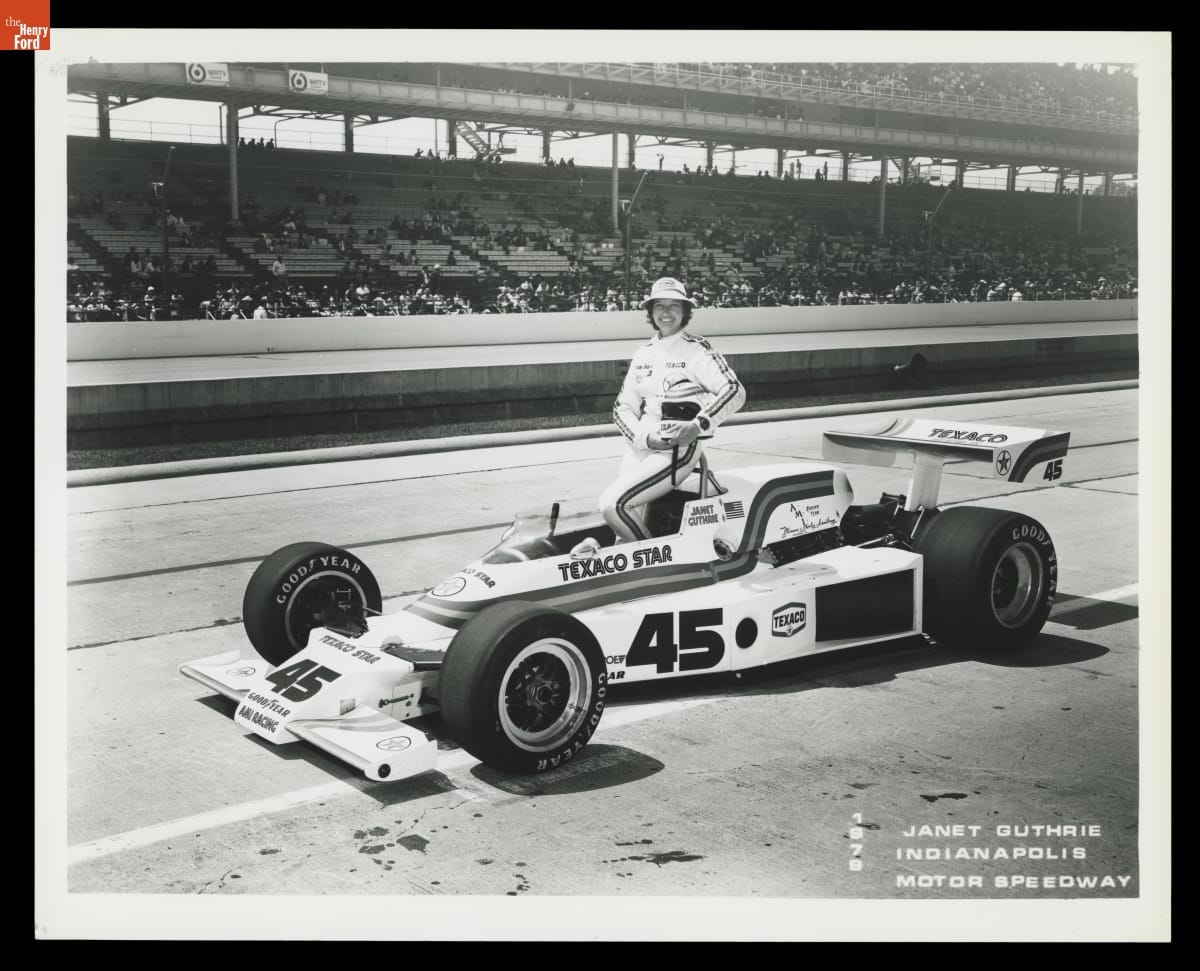

The next most notable female racer was Janet Guthrie, who was the first woman to race in the Indianapolis 500 (1977, '78, '79) and the first woman to compete in the NASCAR Daytona 500 (1977). Janet was an aerospace engineer who was also a pilot and started racing as an amateur in the 1960s in the Sports Car Club of America before being contacted by a car owner to attempt to race in the Indianapolis 500 in 1976. Remember the 1970s was when the women’s lib movement was getting into full swing, so some folks were looking for ways to either give women an opportunity to show their stuff, or on the contrary to set them up to fail when trying to compete in a male-dominated sport.

Janet Guthrie with Lola-Cosworth Race Car at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, 1978 / THF140173

So let me explain a little bit about the unique sport of auto racing. Yes, it’s male dominated because more men showed interest over time and in the early years it was a way to demonstrate vehicle dynamics and capabilities, and since it was an expensive sport, it also took men of means to have the resources to race cars. The women who raced in those early years were often married to or widowed by these men of means. Some women were successful, but it was rare. While it takes considerable physical strength to drive a race car, it is not a sport where physical strength determines the outcome of the race. Flying, equestrian events, shooting, archery, and sailing are other good examples of these sports.

When I started racing in 1974 I really had no idea what I was getting into, but I knew I liked to drive fast and was intrigued with the concept of being able to get behind the wheel (race car) and be anonymous, because it was more about that “car” won the race, rather than the driver. When I watched Billie Jean King beat Bobby Riggs in a tennis match on national television in front of 60 million people, I think that inspired me to “go for it” and try to become a race car driver.

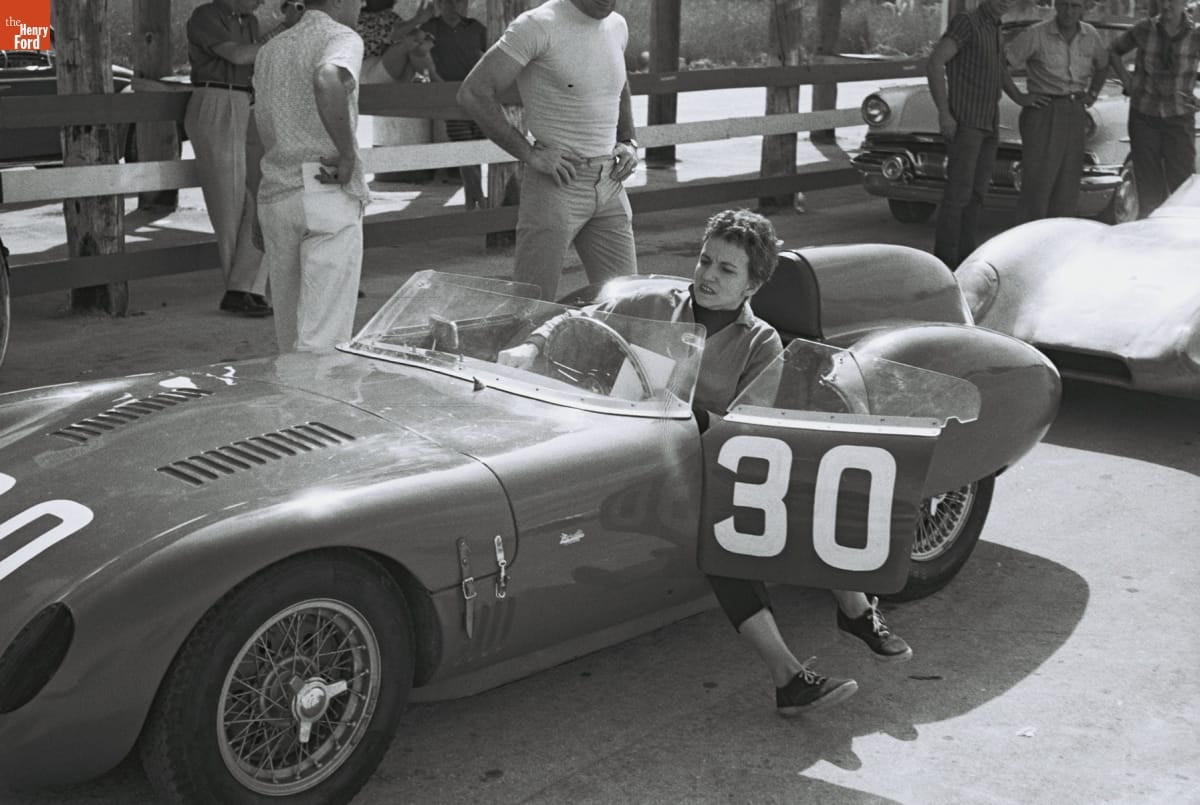

Denise McCluggage at Bahamas Speed Weeks, November-December 1959 / 2009.158.N.591104.1

What excites me today is that there are so many women, young and old, who are showing up and racing cars, motorcycles, airplanes, sailboats, horses, and more. And they are winning again and again and sticking around to continue to learn their craft and earn the respect of competitors, fans, and industry leaders.

- There have been nine women who have raced in the Indianapolis 500 since the first 500-mile race in 1911. There have been only 796 drivers to ever compete in this historic race!

- There are more women racers competing in the National Hot Rod Association (NHRA) than in any other professional racing series, and 23 women have won championships, with the most being won by six-time champion Erica Enders in the Pro Stock Division.

- It is estimated that over 50% of Jr. Dragsters (between the ages of 5-17 years) are females.

- There are more women on podiums around the world than ever before.

- There are women holding leadership positions in motorsports, such as Latasha Causey, President of Phoenix Raceway; Julie Giese, CEO of the NASCAR Chicago Street Race; Connie Nyholm, CEO Virginia International Raceway; Susie Wolff, Managing Director of the F1 Academy; and Deborah Mayer, Founder of the Iron Dames and Iron Lynx race teams.

- There are many women lead engineers in motorsports, such as Angela Ashmore, Chip Ganassi Racing IndyCar team; Laura Muller, Haas Racing F1 team; Hannah Schmitz, Red Bull Principal Strategy Engineer; Kate Gundlach, McLaren Racing Performance Engineer; Amelia Lewis, McLaren Racing Performance Engineer; and Leena Gade, Multimatic Engineer who was the first female lead engineer to win LeMans for Audi.

- This year Betty Skelton is being inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame. Betty was an aerobatics pilot, a land speed record holder, test driver, and automotive advertising executive. She is among only five women in motorsports inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame, joining Janet Guthrie, Shirley Muldowney, Denise McCluggage, and myself, and among the 25 men and women from motorsports.

Betty Skelton at Daytona Beach, 1956 / Courtesy Lyn St. James

When men and women compete together and against each other in sports at the highest level where physical strength is necessary but does not define the results, it demonstrates to the world that there are opportunities for women to compete and contribute to the benefit of making the team better, the business better, the industry better. We have much to celebrate but also plenty of work to do.

There is a saying that is so true: If you can see it, you can be it! Because of the increased participation of women in motorsports, and with the increased awareness of women in sports, in nontraditional roles, and in male-dominated fields, more young girls and women are now seeing what’s possible!

To find more information you can go to: www.womeninmotorsportsna.com.

Lyn St. James is a seven-time competitor in the Indianapolis 500 and co-founder of Women in Motorsports North America.

Think about the dishes, bowls, and mugs you often see in diners and restaurants. What are they like? And why are they designed that way? Diner or restaurant ware is typically made from porcelain or stoneware that has been “vitrified,” turning the material into a glass-like substance via high heat and fusion alongside the glaze.

Restaurant ware is designed for practicality. It is thick and sturdy with smooth and rounded contours, which offers a range of benefits. Restaurant ware is durable, less prone to breaking and chipping, and better at retaining heat to keep food warm. It also can handle extreme temperature changes. The vitrification process minimizes silverware marks on the surfaces, keeps harmful chemicals from leaching into food through food-safe glazes, and resists staining and odors. Plus, the glazes are easy to clean, commercial dishwasher safe, and maintain their glossy finish after many washes.

Stacks of plates, saucers, and bowls at the ready for guests at Lamy’s Diner in Henry Ford Museum. / Photo by Aimee Burpee

History of Restaurant Ware

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, people dining outside the home became more common. Early restaurants and diners served meals on fragile porcelain, porous earthenware, or glass not designed to handle the wear and tear of heavy daily use. As a result, pottery companies began experimenting with stoneware, first creating “semi-vitreous” pieces before moving to fully “vitreous” (or glass-like) ceramics.

Customers eating and drinking using commercial restaurant ware at the counter inside Lamy’s Diner at its original location in Marlborough, Massachusetts. / THF114397

Buffalo Pottery

One of the first and most notable companies to pursue this industry was Buffalo Pottery, based in Buffalo, New York. Founded in 1901 by soap manufacturer John Larkin, the company initially aimed to produce wares that could be given away as premiums for purchasers of his soap products. Buffalo Pottery produced its first restaurant ware pieces in 1903.

The blue-plate special – a discount-price meal that changed daily – seems to have been named after the plate that it could be served on. This plate with divided sections was made by Buffalo China circa 1930. / THF370830

Incorporated in 1940, Buffalo Pottery changed its name to Buffalo China Inc. in 1956. In 1983, It became a subsidiary of American tableware company Oneida, Ltd. After more than a century of manufacturing, the Buffalo factory was sold in 2004, marking the end of its production.

Buffalo Pottery was also known for its art pottery, decorated by artists and craftspeople to showcase artistic aspirations on utilitarian pieces like this candlestick decorated by Mabel Gerhardt in 1911. / THF176916

Syracuse China Company

Another significant manufacturer in restaurant ware production was Syracuse China Company, which originated as the Onondaga Pottery Company in 1871 in Syracuse, New York. The company initially made non-vitrified dinnerware, used both in homes and in restaurants. In 1896 they introduced vitrified stoneware with a rolled edge. By 1924 Syracuse China built a factory dedicated to manufacturing only commercial ware

After World War II, many US corporations, like General Motors, built engineering and manufacturing campuses that included employee cafeterias. Companies such as Syracuse China made dishes, bowls, and mugs or cups with companies’ logos for use in these cafeterias. / THF194982

Syracuse China made dishes for Sears Coffee Houses, small diner-style eateries inside Sears department stores. / THF195542

In 1966 Onondaga Pottery Company officially changed its name to Syracuse China Corporation. In 1993 it became Syracuse China Company, before being acquired in 1995 by Libbey, Inc. a U.S.-based glass manufacturer. By 2009 all production was moved out of North America, bringing an end to 138 years of production in Syracuse.

Restaurant Ware Patterns

Restaurant ware was typically plain or minimally decorated with color and simple patterns. Many companies produced similar designs, allowing diners and restaurants to easily buy replacements or additional pieces from a variety of manufacturers. One popular design was a white background with one to three green stripes.

The white with green stripes pattern on a bowl by Homer Laughlin China Company, 1966 (left) and on a divided plate by Buffalo China Company, 1952 (right). / THF197347 (left), THF197410 (right)

A variation on the green-and-white theme was a design of wave-like or scallops along the rims of bowls, plates, or mugs. Shenango China, America’s second-largest manufacturer of food service wares, called their pattern Everglade. Buffalo China offered a version called Crest Green, while Mayer China referred to theirs as Juniper, and Syracuse China called it Wintergreen.

Shenango China Co.’s Everglade pattern on a cup and saucer, 1961 / THF102560

Another distinctive pattern called “Pendleton” featured a deep ivory or tan base with three stripes: red, yellow, and green. This design was likely inspired by blankets manufactured by Pendleton Woolen Mills since the early 1900s. The Glacier National Park blanket’s colors and markings are reminiscent of those distributed at frontier trading posts in exchange for furs.

Pendleton-pattern ware on display in Henry Ford Museum (left), and a Buffalo China Company cup. / Photo by Aimee Burpee (left), THF197343 (right)

Victor Mugs

Picture a mug of coffee at your local diner. Is it a mug that looks like this?

Victor Insulator mug from the Rosebud Diner in Somerville, Massachusetts. / THF197331

In the late 19th century, Fred M. Locke started Locke Insulator Company (later Victor Insulators) in Victor, New York, to manufacture glass and ceramic insulators for electrical and telegraph wires. By the mid-1930s, the plant in Victor had been retooled with four new kilns when the company was considering expanding into heavy-duty, high-quality dinnerware.

Ceramic and glass insulator made by Locke’s company in Victor, New York, circa 1898, and used on early transmission lines in the San Joaquin Valley, California. / THF175272

When WWII broke out, the U.S. government put out a call for durable dinnerware for use aboard naval ships. The Navy needed coffee mugs that were less likely to slide off surfaces, but if they did, could withstand the fall. Victor Insulators won the contract and began producing thick-walled, straight-sided handleless mugs, each with a rough ring on the bottom. Drawing the company's expertise in insulator technology, these mugs were crafted from high-quality clays fired at 2,250°F. The mugs proved so successful with the Navy that Victor quickly began making mugs with handles for the war effort. The handles were attached by one of three women employed at the factory for that specific task. The mug’s design also evolved, with the introduction of curved sides that made it easier to grip. After the war, these durable mugs were in high demand for diners and restaurants across the United States.

For several decades, Victor mugs were a staple of American dining. But by the 1980s, cheap knockoffs flooded the market, and Victor Insulators found it difficult to compete. By 1990 the company phased out the mugs, although they continue to produce ceramic insulators to this day.

Hot coffee and slice of cherry pie served at Lamy’s Diner on Homer Laughlin China Company mug and plate. / Photo by Aimee Burpee

Aimee Burpee is Associate Curator at The Henry Ford

What We Wore: Cocktail Party

Through mid-April 2025, the What We Wore exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation presents fashionable 1950s cocktail attire. / THF802492

Cocktail parties were the essence of sophistication in the 1950s. Throwing a cocktail party — whether to impress business associates or entertain neighbors — was the “in” thing to do. The American economy was expanding, people were moving to the suburbs, and a return to traditional gender roles put women back in the home as full-time homemakers. Entertaining after work and on weekends became an essential part of business and neighborhood life. Hosts relished showing off their skills as they impressed guests with trendy cocktails and hors d'oeuvres.

Elegantly informal — and often, aspirational — cocktail parties were part of a "see and be seen" culture where every social event had a dress code. For cocktail parties, men wore a dark suit, white shirt, and a tie. Proper attire for women? Stylish semi-formal dresses with either full skirts or slender silhouettes — a polished look, but not overly extravagant.

Suit, 1948. Made by Guild Commander for The Hub department store, Baltimore, Maryland. / THF802440. Gift of American Textile History Museum, donated to ATHM by Robert M. Vogel.

Attending cocktail parties was a must to climb the corporate ladder.

Cocktail dress & jacket, about 1958. Ruth McCulloch, Hubbard Woods and Evanston, Illinois. / THF162635. Gift in Memory of Augusta Denton Roddis.

Cocktail dress, about 1952. Christian Dior, Paris, France. / THF29329. Gift of Mrs. Harvey Firestone, Jr.

French couture houses continued to dictate high fashion during the 1950s.

Cocktail dress, about 1959. Possibly made by Catherine Prindle Roddis, Marshfield, Wisconsin. / THF160845. Gift in Memory of Augusta Denton Roddis.

The “little black dress” has become a wardrobe essential — a simple, versatile, elegant dress that can be dressed up or down depending on the occasion.

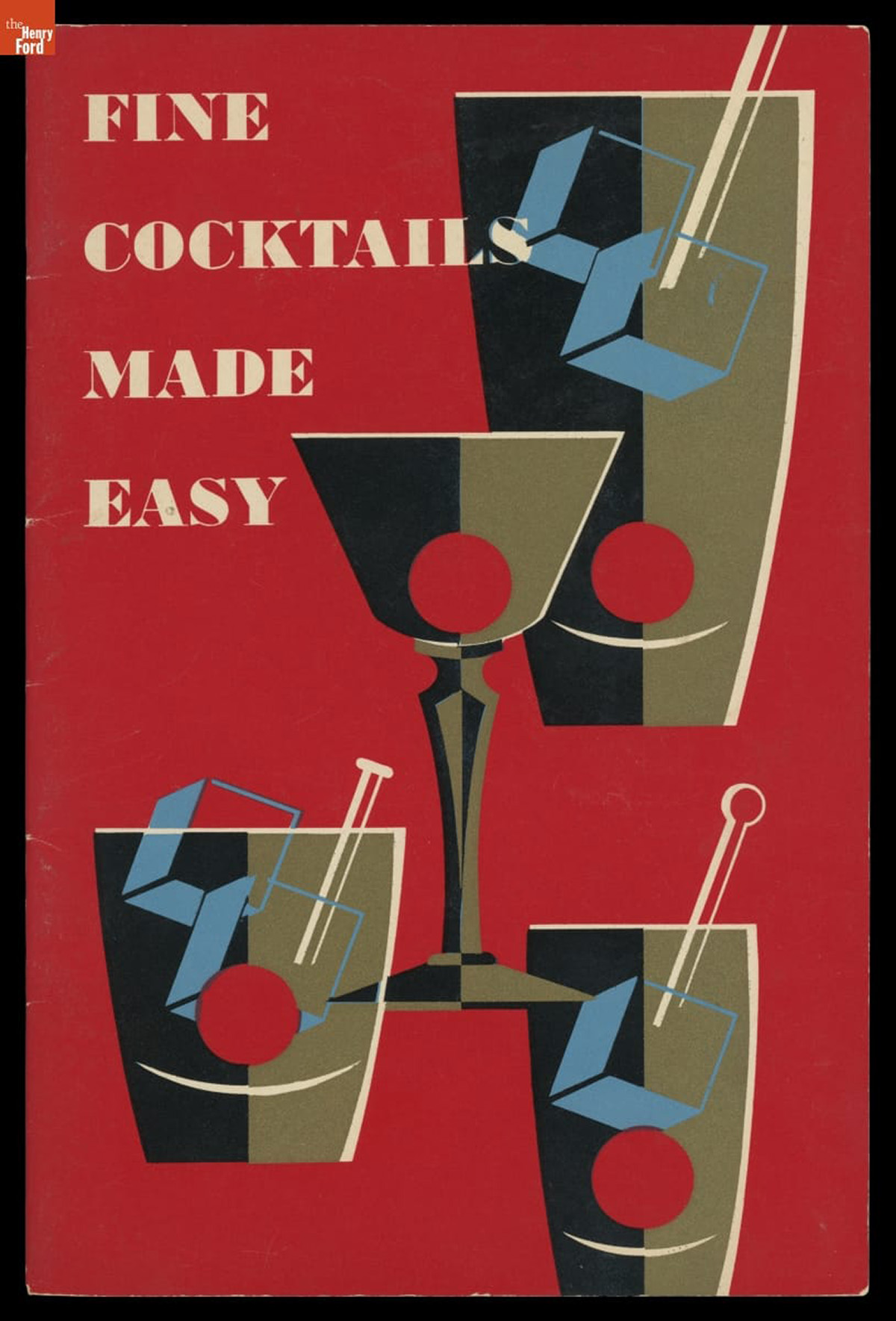

The right drinks and food helped guarantee cocktail party success. Handbooks provided helpful advice and recipes for eager hosts and hostesses. National Distillers Products Corporation, 1955-1960. / THF720273

Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford.

Learning from our Ancestors – Garden Sustainability in the 19th Century

Greenfield Village is host to a plethora of gardens, both floral and vegetable. The Living History and Agricultural teams are responsible for the historic growing spaces to produce the vegetables, fruits, dye materials, and herbs that our ancestors would have relied on — spanning from 1760 through 1930. These items are grown in both kitchen gardens and fields. We can learn from these sustainable systems, and from those that came before us, to make educated decisions for our modern home gardens. Firestone Farm is an excellent example, as it has the most comprehensive growing space, and guests can see the process from farm to table.

Firestone Farm kitchen garden / Photo courtesy of Morgan Lewerenz

The kitchen garden has been the heart of the growing space for home use for many centuries. During the 19th century, the vegetables, herbs, and fruit grown in the kitchen garden were the first used in the house for daily meals. When there was abundance — much of which was planned — then produce would be used in preservation recipes. The cycle of the kitchen garden is just as necessary for human consumption as it is for the annual rehabilitation of the growing space. Gardens serve the home during the growing season and in turn, we give back to the gardens when the plot is uncultivated during the winter. During the cold season, animal waste on the tilled land as well as distribution of compost as the ground begins to warm prepare the garden for the next year of production. Likewise, kitchen scraps could equally go back to the compost and the hogs, providing sustenance for the future. Many agricultural manuals of the time also include instructions on how to use objects on the farm and surrounding lands to build structures in the garden. Guests will often see A-frames and trellises in the gardens made by branches that have fallen and been repurposed.

The field at Firestone Farm / Photo courtesy of Morgan Lewerenz

The field is the backbone of the growing spaces for a farm. This space is often planted with row crops for cellar storage, food for animals, and grains that could be sold. The Firestone Agriculture team includes Turkey Red winter wheat in their annual plantings based on research into the Firestone family in the 1880s. This sellable crop would have been planted in late fall and come spring clover could be broadcasted over the wheat to help minimize weeds from developing. After wheat harvest in mid-summer, the clover would be plowed into the ground to help replenish the soil with nitrogen. Another soil replenishing cover crop, like buckwheat, could be planted between harvest and planting. The buckwheat would then be tilled into the soil before replanting the next season's wheat. Crops like corn were often planted with pumpkins, a testament of Indigenous knowledge of sustainability. The "three sisters" method of planting allowed for the best use of space in the field and the best support system for the crops planted. Guests can see how the Firestone team grows pumpkins in the corn field for that same efficiency as both are harvested at the same time.

"Three sisters" planting at Firestone / Photo courtesy of John Forintos

Composting was essential to the success of growing spaces on 19th-century farms. Many period manuals instructed farmers to use their "thoroughly rotted and rich compost" to supplement nutrients in their garden spaces. The current Firestone teams use a combination of animal and produce waste to create their compost and have even been working with the new biodigester at Stand 44 to supplement plant matter to help keep the mixture balanced. Manure also has to go through a stage of composting before it can be useful in the garden. Guests can see the consistent manure heap, often steaming, near the barn ramp. The manure has to be regularly turned and watered — just like a compost pile. Similarly, the farm team uses a technique called "hard packing" for the animal pens during the winter. This practice allows the manure to be covered with straw, creating layers of buildup throughout the winter. Pens stay clean with additional straw and the animals benefit from the warmth of the straw-manure layers starting to ferment. Then in the spring, pens are deep cleaned and the mature manure/bedding is added to the pile adjacent to the barn ramp.

The Living History and Agriculture teams are using historic methods to care for the growing spaces in Greenfield Village, but this is knowledge that has been around for hundreds of years and much of it is still being used today. We hope that today's gardeners can be inspired by our ancestors to try out some new-old sustainable practices at home!

Turkey Red winter wheat at Firestone Farm / Photo courtesy of John Forintos

Emily Sovey is manager of Living History

John Forintos is manager of Historic Agriculture, Horticulture, Animal Husbandry and Town Life

Morgan Lewerenz is master farmer of Historic Agriculture

Kelly Salminen is a Firestone Farm program specialist

A Storyteller’s Perspective

Author and filmmaker Nelson George leans into a discussion about how obstacles, objects and observation are the makings of a good story

Nelson George has had an amazing career. He’s an author. A screenplay writer. A filmmaker. An award-winning journalist. And he’s not done yet.

Photo by Erik Tanner/Contour by Getty Images

Broadly speaking, much of George’s professional portfolio has been focused on the documentation of the Black experience in America. His publication record includes both novels and celebrated nonfiction works like Where Did Our Love Go?: The Rise and Fall of the Motown Sound and Blackface: Reflections on African-Americans and the Movies. He also has credits as a writer and producer on Netflix's The Get Down and has co-written screenplays for iconic 1990s films including Strictly Business and CB4 starring Chris Rock.

Over the decades, George has built upon his skills as a prolific storyteller. He has an unwavering understanding of the human condition from myriad angles and readily relies on his keen observation skills to bring stories of people overcoming obstacles and realizing their dreams to the page and screen.

Recently, Kristen Gallerneaux, curator and editor-in-chief, and Jennifer LaForce, The Henry Ford Magazine’s managing editor, had the opportunity to talk with George as he begins to contemplate and activate his approach to documenting the next chapters in the story of the Dr. Sullivan and Richie Jean Sherrod Jackson House, one of the newest acquisitions of The Henry Ford. This Selma, Alabama, home provided a safe haven where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and hundreds of others invested in the Voting Rights Movement worked, collaborated and strategized the Selma to Montgomery marches of 1965 (learn more). George will be creating a documentary about the house’s significance to the Long Civil Rights Movement, the backstory of its move from Selma, Alabama, to Dearborn, Michigan, and its reconstruction in Greenfield Village (learn more).

Kristen Gallerneaux: You’ve worked within many forms of media during your career — as an author, a screenplay writer, filmmaker, documentarian, journalist. What have you learned about people and their relationships with one another?

Nelson George: The way that people relate to each other is through story. Think about the people we meet. We ask where they’re from. They tell you “I came from here. I went there. I got married. I got divorced.” Whatever our stories, they are the unifying way that we communicate with each other.

In any medium I work in — whether it’s a book or a movie or a documentary or some other form of storytelling — it’s all about finding the beginning, finding the middle and finding the end. And I think that people relate to each other best when they feel there’s a story that they can connect to.

It’s kind of funny. I do a class once a year in London at different institutions for young artists. It originally started out as a screenwriting class. What I’ve noticed over time is that there are so many different technologies at work today to tell a story — from TikTok to AI — but ultimately it’s about engaging people. I try to teach that if you start off with a star, and then tell how that star was born and then share that star’s journey, that’s the best way to engage someone. For me, the one thing I take away from all the different work I’ve done in all the myriad of forms is that whether it’s about love, an athlete or politics, people really connect when you’re able to communicate in a story form. Tell a story well, and you can bring almost anybody into your world and into your space, and make them connect with you.

Jennifer LaForce: What are some of the nuances of successful storytelling? Those skills and expertise that you use to make that connection with people?

Nelson George: It’s all about the obstacles, because obstacles create goals. When you engage with anybody’s story, whether it’s Willie Mays coming out of the Jim Crow South trying to become a major league baseball player or Michael Jackson who is making an album and knows that the record industry and formats like MTV are very reluctant to play Black artists. Or if it’s Tupac Shakur. Working as an executive producer on the Dear Mama docuseries (editor’s note: focused on the lives of activist Afeni Shakur and her son, musician Tupac Shakur), there were a big number of challenges to explore. Not only how do you overcome a life of poverty, but also your mother is a political figure — and a radical political figure at that — and how does that jive with your commercial career as a recording artist? What are the contradictions in that?

Anytime you have a story with an obstacle, it’s about the “what happens next.” People are like, “Oh, what are you going to do?” Overcoming is a huge part of storytelling. It’s like when you have a love story. It may always end with the wedding, but there’s a whole bunch of obstacles in-between — whether they’re family, racial, financial, distance — before they’ve reached the goal. That’s why love stories are so compelling because we know the outcome we want to see, but what we want to know is “how do they get there?”

Kristen Gallerneaux: Speaking of obstacles, you’ve handled some of those stories rooted in the music scene. Thinking, for example, about your book Where Did Our Love Go?: The Rise and Fall of the Motown Sound. Why is it important in storytelling to understand what it means to be true to yourself?

Nelson George: I’m not sure that most people know what their authentic self is. I don’t think they know until they do something. It’s only in action that character is really truly defined. Decision reveals character, and so in any narrative, those moments of decision are the crucial ones.

I’m currently working on a book about a neighborhood in Brooklyn in the ‘80s and ‘90s that [film director] Spike Lee came out of, and the many decisions Spike made during this time. One that was the most important for the neighborhood was that while most young filmmakers with a successful first film would have gotten an office in Manhattan to run a production company, he decided on a spot, literally, like five blocks from his house. By having the production company in Brooklyn in 1987, it helped transform the neighborhood. People had to come to meetings in Brooklyn. His crews wanted to be close to where the work was, so they moved to Brooklyn. Actors working with Spike started staying in the neighborhood. All of a sudden, the neighborhood becomes “cool,” because Spike is there.

That one decision against the orthodoxy, which is Manhattan, has a tremendous effect on a neighborhood and a generation of artists. Some make the argument that Spike deciding to stay in Brooklyn is one of the key things that led Brooklyn to becoming this kind of cool cultural center.

It’s about decisions you’re making, not knowing what the ramifications are going to be later down the road, right? There’s a certain fearlessness to it. There are always unintended consequences of your decisions — sometimes good, sometimes bad — but when we make decisions, we’re making them based on the information we have and in light of our own desires. You just never know what that’s going to do, how that’s going to ripple.

Picking up further on that … You know Berry Gordy could have decided he’s just a songwriter, and he’d have been a success. He’d written songs for Jackie Wilson that were hits, and he could have easily moved to New York and tried to get in the Brill Building and become one of those songwriters. Instead, he opened up the spot [Motown’s Hitsville U.S.A.] on West Grand Boulevard. He made a decision to stay home, and that decision transforms his career — and Detroit.

Kristen Gallerneaux: It’s amazing the breadth of publications that you have, shifting between fiction as well as really deep, scholarly nonfiction and these poetic portraits of well-known characters. And let’s extend that out to your screenwriting credits as well — I know that you worked on The Get Down and Strictly Business, which is iconic. Have you ever had difficulties bringing a character or a subject to life? And on the flip side of that, how do you do it, functionally?

Nelson George: I think it goes back to obstacles. On The Get Down, for example, we had these young artists who were not even really artists yet. They were just kids who wanted to perform or wanted to get out of the Bronx. One of the things we did in the first episode was to introduce a record — the rarest record in New York. That “device” then allows you to meet the lead characters in the story.

Baz Luhrmann, who executive produced The Get Down, came into our office one day and he did a whole lecture on devices. Devices, in a film way, is an object of desire, or for the characters, an object that becomes symbolic of a larger search for identity. It’s a really great technique in terms of trying to figure out how to get a story going. Give someone a goal, but not just a general goal — a specific goal that involves an object.

Think about The Maltese Falcon, the famous detective story. Or the guy in Citizen Kane. He’s looking for Rosebud. If you look at classic literature, classic films, often there is a device or a thing that actually becomes the “way” or what people are looking for. In The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, it’s about these rings. They’re tangible. Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing is about the pictures on the wall of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria in Brooklyn.

You have characters, you have goals, but what embodies them is wrapped around tangible pieces.

Kristen Gallerneaux: In The Get Down, it would also be the turntables and equipment that you need to learn to DJ, right?

Nelson George: Right! That’s tangibility. You have a goal and you’ve given your characters an object that becomes a representation of all their dreams.

Kristen Gallerneaux: I love that. It’s really interesting too, because people, even once they acquire that object, they make choices and decisions that can sway their life in any number of directions around that object. The goal tied to objects allows you to create character.

Nelson George: Yes. In general, I like to use reality to create. It’s where I’m more grounded. I’m taking from life, right? That to me is looking at things that have been done and seeing if there’s a way to do them differently. For example, I did a bunch of detective or noir novels. The first was called The Accidental Hunter. Basically, I saw the movie The Bodyguard with Whitney Houston, and asked myself, “What if she was white and the bodyguard was Black?” That very simple thought led to me writing that novel, and that led to me writing five more novels with the same character. Sometimes it’s just a matter of seeing something that was good or interesting, and looking at it from a different angle.

Jennifer LaForce: Not everyone is capable of that type of foresight or observation. Would you say you have strong observation skills?

Nelson George: That’s the beauty of growing up in New York: great people-watching. You can sit on a bench in the summertime or, for that matter, be on the subway and see so many people. “What kind of sneakers is he wearing? I’ve never seen those before.” You see a woman who’s got a shopping bag and you can tell that her nails have not been done in a while, and you go, “Oh, she’s a mother or working-class woman. She hasn’t had time to do her nails because she’s busy.” You start observing people, what’s particular about their attire or their body language and stories can begin to come from that. New York has been big in terms of the observation part of my career.

Jennifer LaForce: Were you always that observant person? That person who wanted to tell a story?

Nelson George: I remember reading Hemingway, The Nick Adams Stories, and thinking, well, he’s writing about a kid living in Michigan, and it’s very detailed. You know that Hemingway style — very descriptive — and you had to read through what he was seeing and feeling. That really stuck with me. When I was about 15, 16, 17, I started writing stories based on a character living in Brooklyn, and it was totally because of reading Hemingway and trying to mimic the masterful style. It definitely put me on a path that understood how external details of a place and of a person can be incredibly revealing. I give Hemingway a lot of credit as one of my influences in terms of harnessing observation.

Kristen Gallerneaux: As a seasoned storyteller, why is it important for us to tell stories of our past, keep our histories at the forefront?

Nelson George: History is a tool to understanding how we got to the places we are. I think that Americans in general have a very superficial sense of history, and they tend to make the same mistakes over and over again.

History can be extremely instructive in understanding why we’re in the positions we’re in, economically, culturally, government wise. At the same time, there are techniques that were employed in the past that are still applicable now. Yes the technology changes, but I don’t think the human condition changes necessarily as deeply, so there are ways in which we can use ideas and philosophies of the past to move forward. I also think history allows us to “see.” Going back to my comments about obstacles, we can see how obstacles that got in the way of individuals were overcome. That’s where the inspiration part comes in and where history can be so useful.

Any museum, particularly ones that are collecting objects from the past, can really inspire people, too. The scale of The Henry Ford is really kind of stunning in terms of that.

Kristen Gallerneaux: Yes! I think not only the scale but also the breadth of the collections of The Henry Ford are sometimes a shock to people. What role do you see institutions such as The Henry Ford playing in the documentation of everyday Black and African American culture and history?

Nelson George: We talked about Spike’s decision about Brooklyn. We’ve also talked about Berry Gordy in Detroit. These buildings, these sites, are really only significant because of a person’s decision to use them as a headquarters for potentially historic things.

At The Henry Ford, I see a building like the Jackson House representing a similar significant location.

Why was this place selected and why did Dr. King and his advisors think it was the right place to be? How did the Jackson family create an environment supportive of these efforts? How did their daughter, Jawana Jackson, realize the value of what happened in her home and document it and preserve it the best she could for over 50-plus years?

Greenfield Village has so many spaces like this that represent different moments in American history — that represent the efforts of hundreds of thousands of people to create a better America. Hopefully the Jackson House project will pay tribute to the efforts that took place there and the efforts that were made to maintain this structure.

Kristen Gallerneaux: We’re so lucky that Ms. Jawana Jackson and her husband, James Richie, believed in this project and maintained stewardship of the house and its stories over such a long period of time. I’m sure there were points of exhaustion as they dealt with the ambivalence that brought the house from Selma to Detroit in the first place.

Nelson George: In retrospect, they were not getting a lot of support from the state of Alabama. And those specific obstacles, they will definitely be a part of the storytelling of my film. What happened? Why was the house not supported? It’s one of the ways I hope to create empathy for Jawana’s and her husband’s efforts in the face of great indifference.

This post was adapted from an article in the Winter/Spring 2025 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

Dick Gutman: The Beckoning Diner Stool

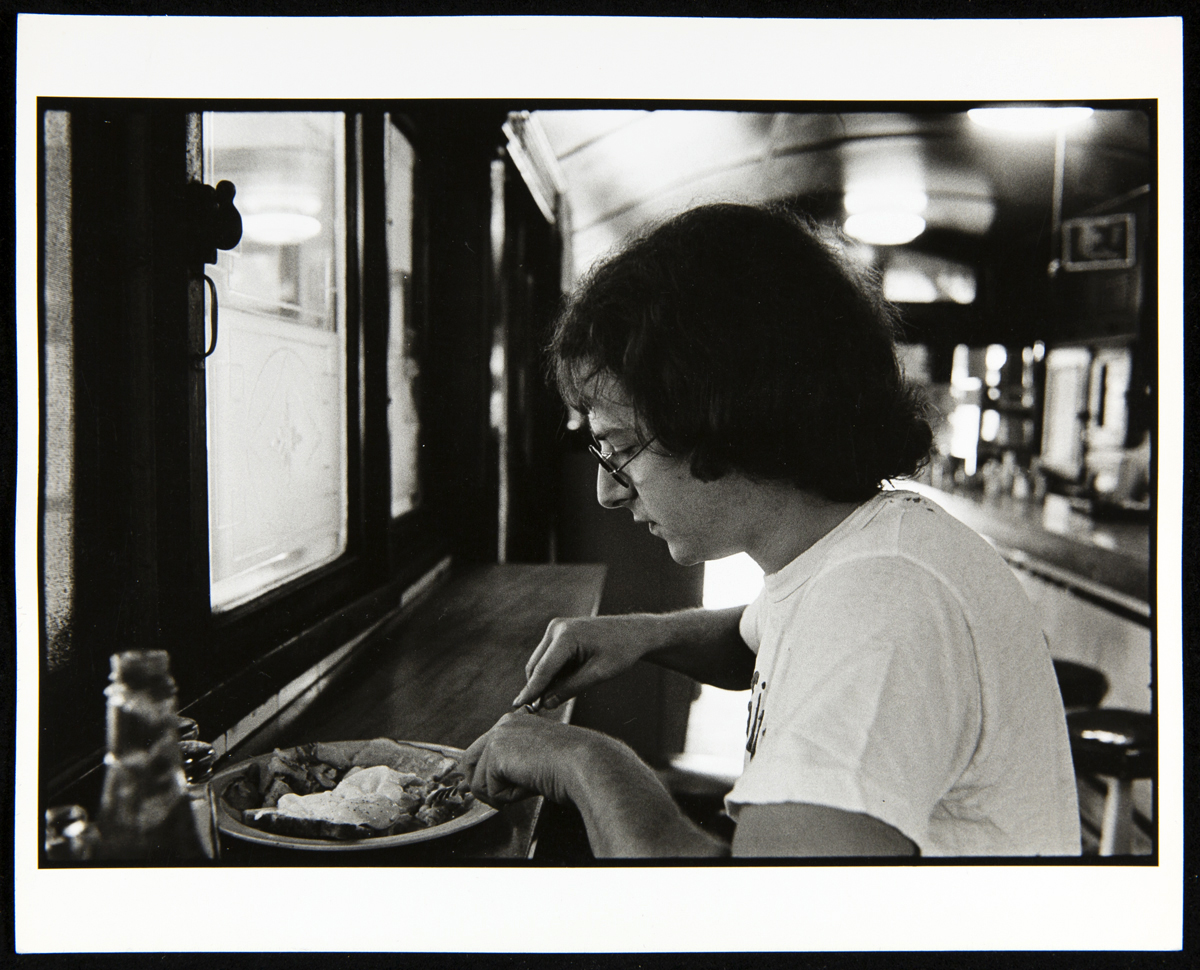

Richard J.S. Gutman in the Kichenette Diner, Cambridge, MA, circa 1974. Photograph by John Baeder. / THF297027

The diner, it seems, is irresistible. The sleek diner in a streetscape, the booth as setting for friends and family getting together, the beckoning counter stool for the lone traveler’s brief stop—all of it has become cherished over generations—the diner as a world within the greater landscape of people’s lives. For over half a century Richard J.S. “Dick” Gutman has been immersed in this world. He has spent his career living and breathing his way through the origins, design, operation, and stories connected to diners. Starting academically with his architecture thesis at Cornell University, his interests and efforts expanded and have continued to the present day through an active roster of publications, research, lectures, and restoration consultations.

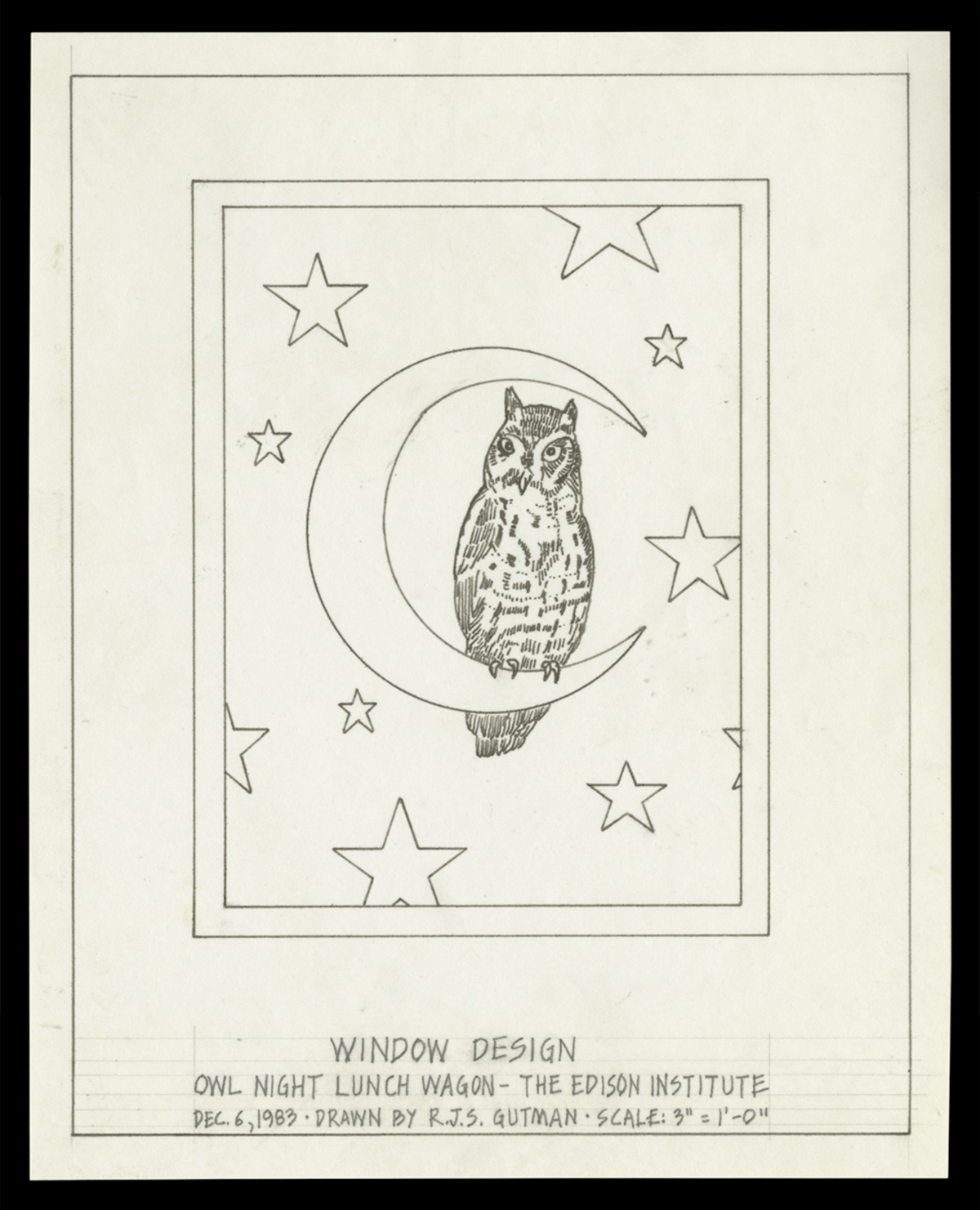

Window design drawn by Gutman during the restoration of the Owl Night Lunch Wagon, 1983. / THF715111

Much has already been “dished” about Gutman’s foundational years as an architectural historian specializing in American diners. Most recently, we were treated to a guest feature in The Henry Ford Magazine, penned by Mr. Gutman himself. Likewise, since the 1980s, he has worked as a consultant at The Henry Ford on guest-favorite projects such as the Owl Night Lunch restoration, the relocation of Lamy’s Diner, and collaborating to ensure the historical accuracy of Lamy’s menu.

In 2019, Mr. Gutman generously donated his diner collection to The Henry Ford. This collection includes everything from architectural fragments and interior fixtures to menus, trade magazines, historic photographs, and Gutman’s own photographic documentation. A rich and unmatched resource, co-curators Kristen Gallerneaux and Marc Greuther were honored to look deeply into this collection to create the temporary exhibit, Dick Gutman, DINERMAN (on view 25 May 2024 - 16 March 2025). A selection of the less-explored areas of this collection that are included in this exhibit are gathered here.

Dick Gutman, On the Road

In 1975, when Gutman was 25 years old, he met Charles Gemme from the Worcester Lunch Car Company. Gemme—who was 95 at the time—wrote down a list of diners that Gutman should visit. Gutman hit the road with his camera. Typically he traveled alone but was sometimes accompanied by his wife Kellie or fellow diner-obsessive and painter John Baeder.

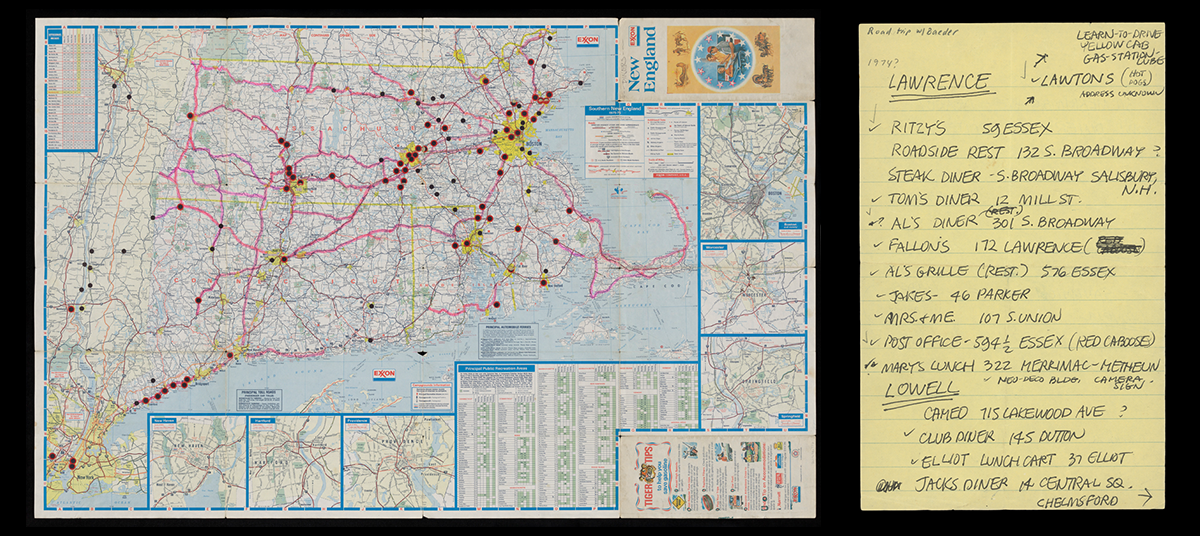

New England road map used by Dick Gutman with locations of diners indicated, circa 1975 (left) / THF715142; A diner list used during a 1974 road trip by Gutman & painter John Baeder (right) / THF714577

In an interview, Gutman described his challenges on these early trips: “Some [diner owners] didn't want to talk to me. They were too busy, they didn't understand it. They didn't like that my hair was too long. They thought I was from the health department.” But eventually, he began to break through: “I unearthed the history of diners by visiting and photographing them and talking to the people who owned them and the people who built them.”

The Fenway Flyer diner, as photographed by Dick Gutman in August 1971. This is the first photograph of a diner that Gutman took. / THF714873

Gutman’s collection contains an important “first,” in the form of a photograph. “The first diner I ever took a picture of was the Fenway Flyer. You have the slide, and it has a light leak. It's the first picture on my roll and I hadn't rolled the film in enough. I only took one picture like that, so it's timestamped in that manner. It was demolished around 1975.”

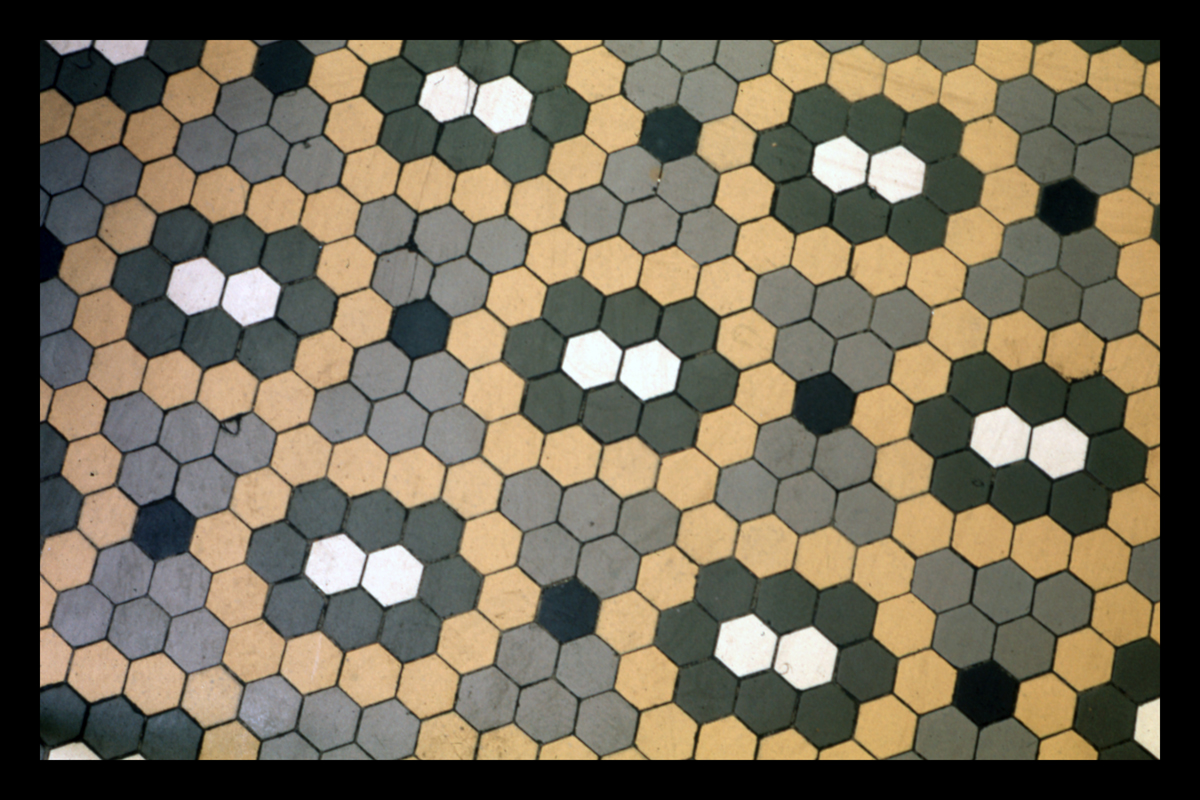

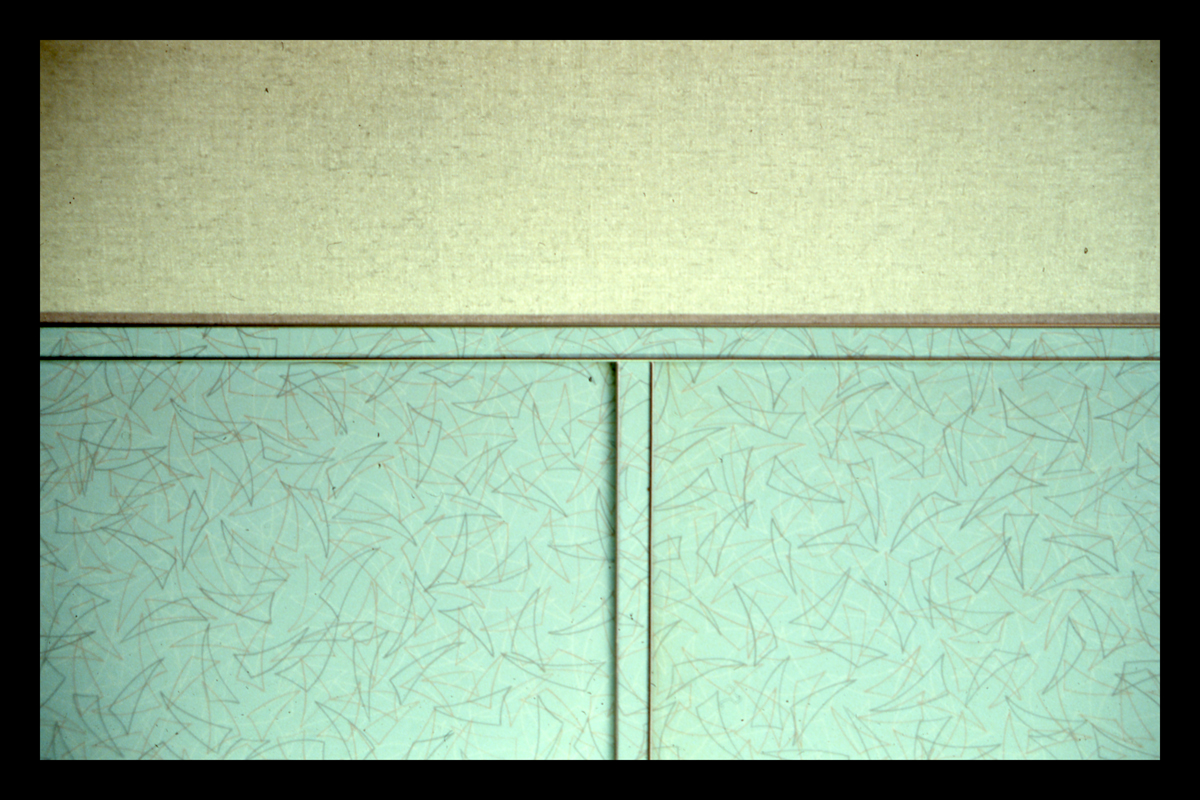

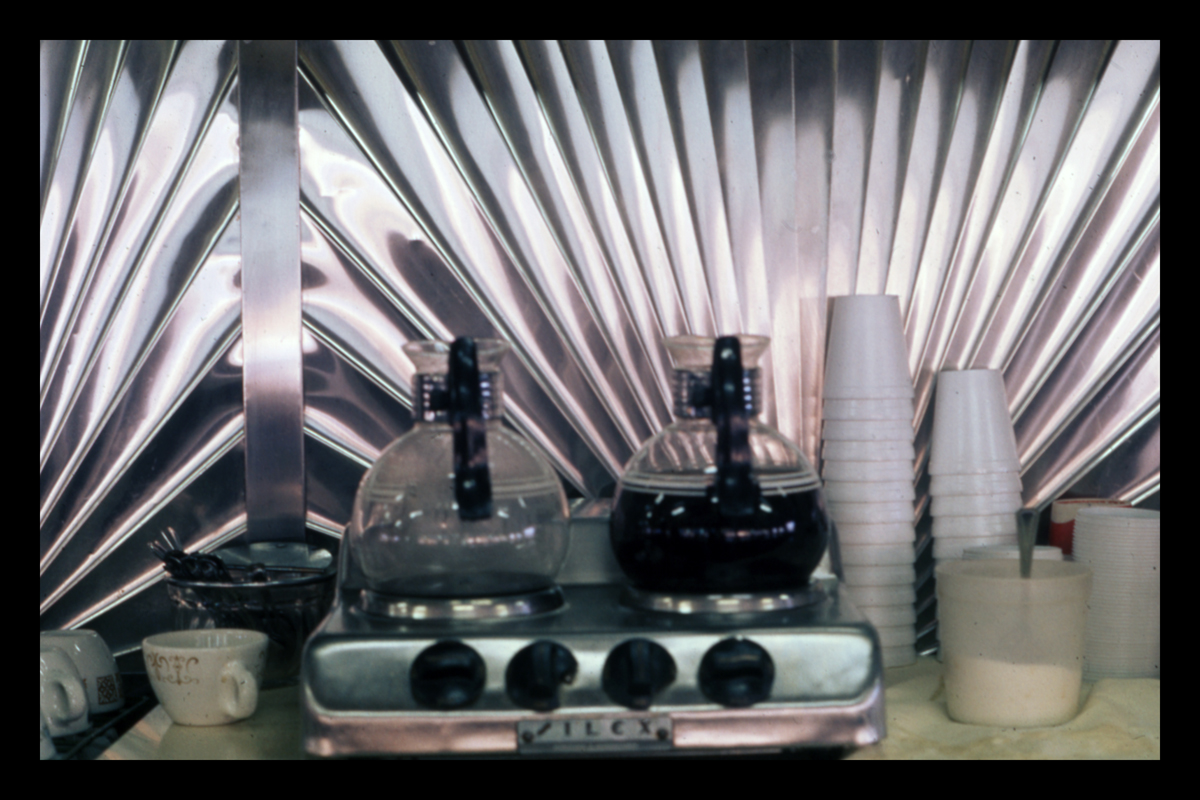

Gutman’s photographs of diners—largely concentrated in the 1970s through the early-2000s—are an invaluable time capsule planted at the intersection of unique architectural history, homegrown entrepreneurship, and community memory. They document the surface-level details of the type of visual flare that diners are known for: decorative tile, flashy steel and Formica-clad surfaces, and colorful, attention-seeking enamel signage.

Lettering on a porcelain enamel diner façade, Peerless Diner, later Four Sons Diner, Lowell, Massachusetts. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714788

Floor tile in Jimmy's Diner, Bloomfield, NJ. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714819

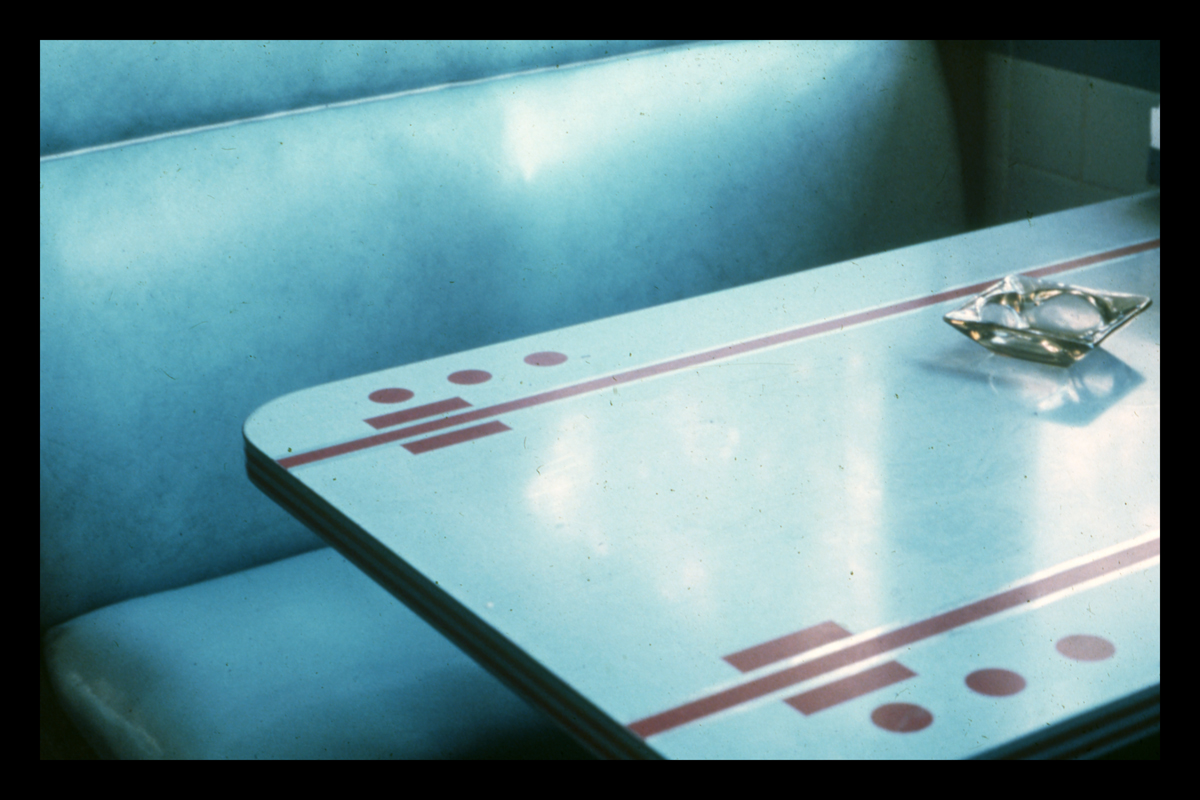

Formica at Deepwater Diner, Deepwater, NJ, 1987. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714808

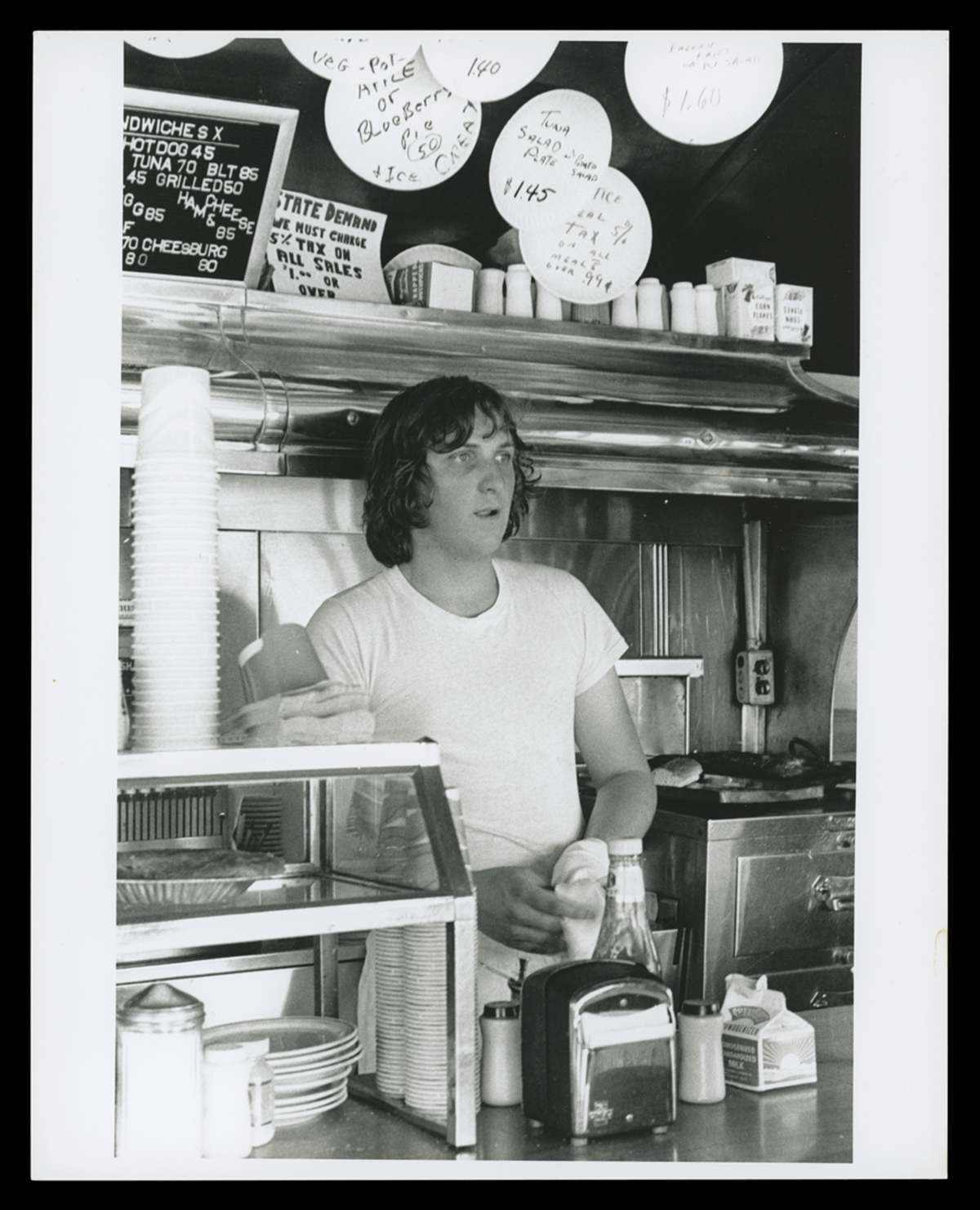

Notably, Gutman turned his camera to the details of interior spaces as well. He photographed employees moving through the nuanced workflows of confined diner spaces—spaces where everything was always on view. We see evolving uniforms, optimized grills, cluttered cashier’s booths, handmade menus, and shorthand orders scribbled on tickets. While Gutman’s collection contains a Wunderkammer’s-worth of disposable goods—paper coffee cups, toothpicks, serve ware, and paper hats—it is within these images where we are given a glimpse of these items situated within the “diner in action.”

Coffee pots in front backbar clad in sunburst stainless steel panels, Phillips Diner, Woodbury, CT. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714795

Cook Kenny Barrett inside Buddy's Truck Stop, Somerville, MA, circa 1974. Note the handwritten specials on paper plates. / THF715018

Less acknowledged in these images—but of great significance—is Gutman’s use of the camera to hint at those most elusive of sensory memories connected to the diner: a sun-drenched ashtray on a table that you can almost smell, vinyl-covered stools that stick to the back of your legs in the summer, the intense concentration of waitstaff leaning in to hear your order, the sizzle of the flat top grill cutting through the din of conversations, a sleeping baby on a booth table—oblivious to it all (or perhaps dreaming of diners). Enigmatic and unpretentious at once, these fleeting moments of the everyday that fill Gutman’s photography portfolio throughout the 1970s-1990s are deserving of our attention.

Booth in Village Square Diner, Grand Gorge, New York, 1973. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714814

Original 1938 porcelain enamel stools in Silver Top Diner, Providence, RI, 1973. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714811

Server taking orders at Collin's Diner, North Canaan, CT, 1972. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714846

Customers seated in a booth at Collin's Diner, North Canaan, CT, March 1973. Photograph by Dick Gutman. / THF714844

Diner Archeology

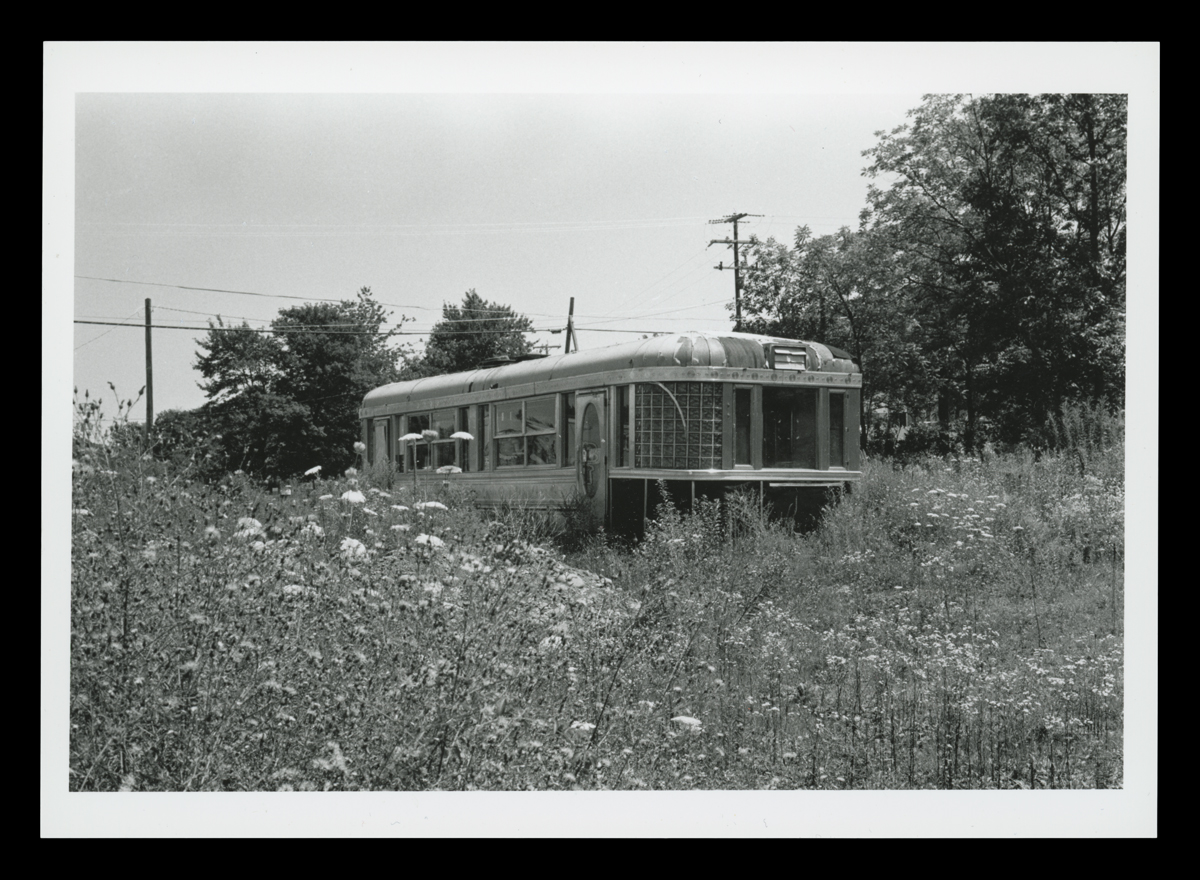

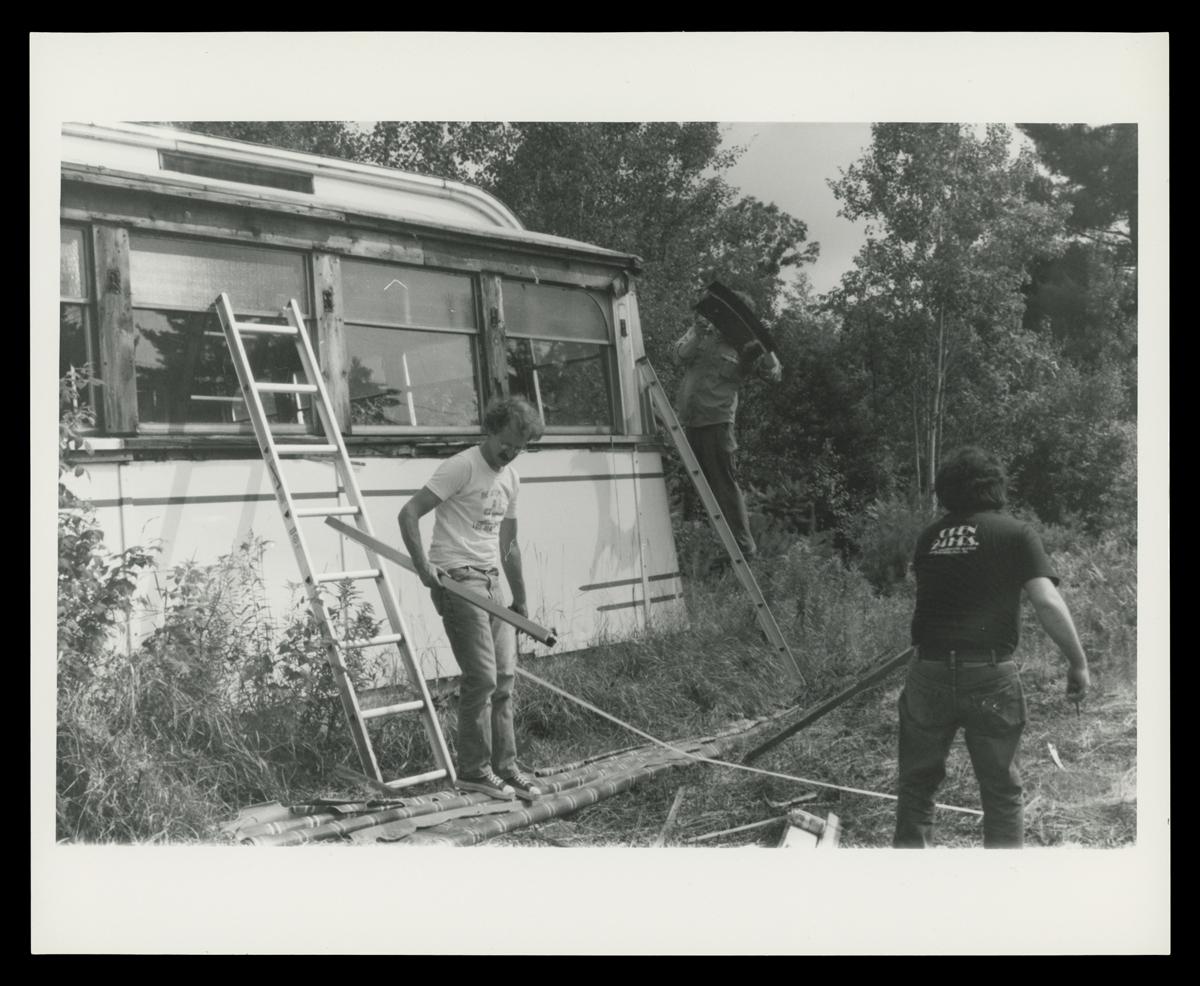

As Gutman quickly learned, diners were on the decline. He realized that his first visit to a diner might turn out to be the last. All too often, he would return to a business after a short time to find the windows boarded over with for sale signs. Even worse, there were the times when he would find himself staring at a rubble-filled lot—the building demolished.

The former "Uncle Wally's," a 1950 Paramount Roadking model diner in a field, circa 1975. / THF714969

Richard Gutman (left) and Larry Cultrera Dismantling Corriveau's Diner for salvage, Gilmanton, NH, August 1985. / THF715129

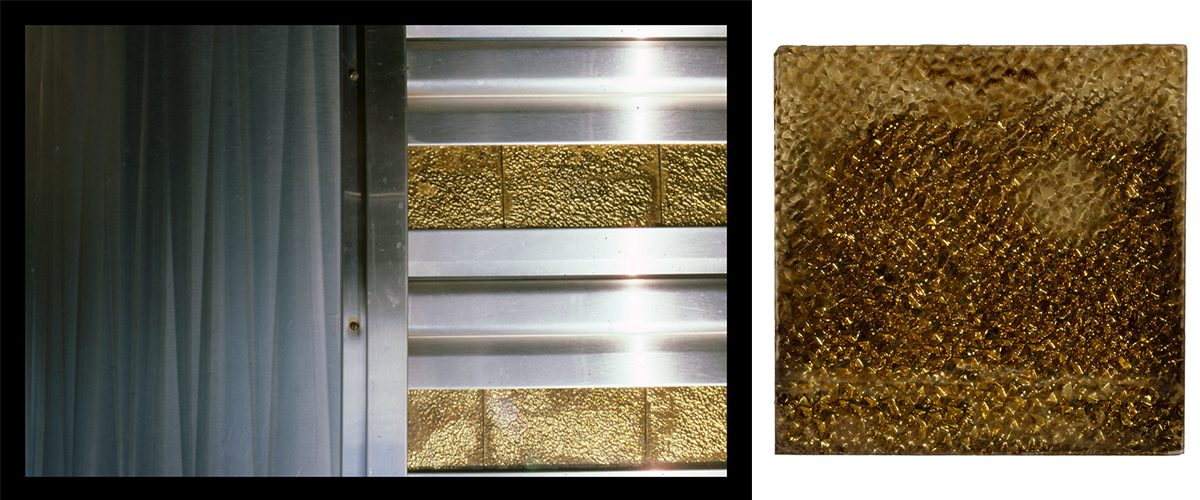

These experiences led to Gutman’s impulse to begin salvaging literal fragments of diners: chunks of tile floor lovingly laid by hand generations prior, a craggy section of Formica bearing the iconic pink “Skylark” pattern, and sparkling jewel-toned Flexglass tiles. They formed an essential reference library for Gutman’s restorations, providing physical proof of surprising trends in materials, interior designs, color, and patterns that filled diners.

"Skylark” pattern Formica fragment, from the Americana Diner, 1952-1953. / THF371317

Flexglass and stainless steel cladding on Key City Diner, Phillipsburg, NJ (left) / THF714804; Flexglass tile from the Lincoln Diner, Kensington, CT, circa 1960 (right) / THF371079

Sometimes, Gutman received news of a diner closing and was able to work directly with its owners to recover decorative panels, menu boards, and historic counter stools. During these salvage operations, he was careful to document where even the tiniest shards originated, which—over decades of collecting—might be reunited with additional ephemera from the same diner. While some may find this type of collecting strange, Gutman extracted these fragments of the past from the field as a way of preserving the future.

Gutman noted in a recent interview: “One of the great tile finds was in Rhode Island. I was photographing Snoopy's Diner and I had to go across the road to get the picture. […] I'm carefully backing up to make sure that I don't fall down the hill. And I look, and there's the remains of another diner. Instead of hauling it away, they just bulldozed the thing! A lot of it had rotted, but there were still the indestructible ceramic tile walls and floor—which I picked up some massive pieces of and put in our car. They're now part of [The Henry Ford’s] collection. Not exactly like Pompeii or Herculaneum—but they have a story to tell.”

Wall tile fragment mentioned above, from the site of a Worcester Lunch Car in North Kingstown, RI, 1920-1939 (left) / THF197842; Floor tile fragment from Hodgin's Diner, York Beach, ME, circa 1915 (right) / THF197841

Beyond their importance within the built environment, diners have impacted our culture, communities, and of course foodways at a national scale. During a time when the American diner seemed to be rapidly disappearing, Dick Gutman raced to document this landscape. This undertaking was crucial to preserving and raising awareness of these easily-lost commercial forms of architecture. We at The Henry Ford are grateful to act as the repository for the incredibly prolific tapestry of research, images, and objects that Dick Gutman gathered.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communication & Information Technology. This blog excerpts and expands upon exhibit labels written by Kristen Gallerneaux and Marc Greuther, co-curators of Dick Gutman, DINERMAN.

The Sweetgrass Basket: An African American Tradition

Visitors to the “Lowcountry,” the coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia — which include the historic cities of Charleston and Savannah — always notice the distinctive stands selling coiled "Gullah" or sweetgrass baskets.

In this image, Gullah sweetgrass basket vendors are visible selling their wares in front of the Old City Market Shed, Charleston, SC, 2010. Photograph by Brian Stansberry.

Throughout Charleston and especially in neighboring Mount Pleasant, vendors line roads selling these homemade crafts, some exquisitely intricate, to locals and visitors alike.

The art of sweetgrass basket weaving is practiced in coastal and barrier island communities from North Carolina to Florida, a region known as the Gullah-Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor. The Gullah-Geechee people are the descendants of enslaved West Africans who worked on coastal plantations. Because of their isolation, they were able to hold onto many traditions during multiple generations of enslavement in the United States.

The Gullah region once extended from southeast North Carolina to northeast Florida.

Slave traders abducted African people from the west coast of Africa to the South Carolina Lowcountry beginning in the early 18th century. As part of their work on the rice plantations, enslaved persons made these utilitarian baskets, generally for the storage of dry goods, although some of the baskets were so tightly woven that they could be used to store liquids too. Flat baskets called "fanners" were used in the winnowing of rice. Britannica notes that once the rice was harvested and pounded in a pestle with a mortar, a fanner was used to toss it upward into the wind, which blew away the husk, or chaff.

An example of a fanner basket described above, dating to before 1863. From the Collections of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of African American History and Culture.

According to Britannica, among enslaved persons, “baskets were made by using a sewing technique rather than a plaiting or braiding technique, unlike baskets of European origin. Long ropes of needlegrass rush (Juncus roemerianus; called bulrush, rushel, or needlegrass) were coiled, one on top of the other, and the coils were held together with strips of white oak bark or saw palmetto. Today makers prefer to use sweetgrass with needlegrass rush and longleaf pine needles (Pinus palustris), sewing these with palmetto leaf (Sabal palmetto), and they produce designs without dyes by alternating the natural colors of the dried yellowish green sweetgrass, reddish brown, black needlegrass rush, and green longleaf pine needles. The only tools required for basket production were scissors and 'sewing bones'— filed down teaspoon handles — or 'nail bones' (made from flattened nails or rib bones of a cow or pig). The 'bones' were used to tuck the palmetto around the coils."

In general, men collected the materials that women transformed into baskets. Depending on its size and function, a single basket could take weeks or even months to make according to Britannica. These baskets (which remained the same for more than 300 years) relied on the sharing of traditional knowledge across many generations, as mothers taught their daughters the technique to create them.

A sweetgrass basket from 2011, made by Carol Lee Howard, born in 1958 in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. / THF802432 (left), THF802433 (right)

This basket is a typical representation. It recently came into the Henry Ford collection from a donor who acquired it in South Carolina. When it was offered for the collection, all we had was a price tag, with the maker's name and a receipt from 2011. After a bit of sleuthing, we located and contacted the maker, Carol Lee Howard.

Ms. Howard grew up in a family where sweetgrass baskets were a family tradition, spanning generations. She says that her mother, grandmother, and all her aunts and siblings learned how to make these baskets for "extra income." As a young person, she was reluctant to make them until her sister Lillie Howard (who died in 2011) challenged her to make them in the early 1980s. Carol Lee accepted her sister's challenge and now views the making of these baskets as part of her family's heritage.

She said that she became serious about making baskets in the early to mid-1990s, selling them at fairs in Charleston, and through local venues. Today, she spends her time taking care of her grandchildren and occasionally making baskets. This recent acquisition represents Ms. Howard's expertise as a basket maker — and the enduring traditions of resourcefulness and resilience found in American craft movements.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford.